Edward Winter

‘I decided to give up chess.’

Thus wrote Botvinnik on page 108 of his autobiography Achieving the Aim (Oxford, 1981). The period in question was 1946 (and not 1941 as stated in C.N. 48), and Botvinnik’s decision was prompted by the Soviets’ repudiation of a gentleman’s agreement concerning arrangements for the planned world championship match-tournament.

Mikhail Botvinnik

In a statement dated 13 March 1924 which was published on page 161 of the September-October American Chess Bulletin of that year, Capablanca declared:

‘I wish to announce that it is extremely doubtful if ever again I participate in an international tournament. Only the fact that [New York, 1924] was the first big tournament in the United States for the last 20 years made me come to play, as for the last year, since my father’s death, I had decided to practically retire from hard chess competition. I expect in the future to play only occasionally in public exhibitions.

As for my title of world’s champion, I would gladly relinquish it, but, feeling that the young players have a right to fight for it, I shall patiently wait a few years at least until one of them comes up to expectations and beats me in a match for the title. If by chance it should happen that I manage to retain my title for some time yet, I shall then see what steps can be taken for me to retire without giving the other players any just cause of complaint.’

In a further declaration, dated 31 July 1924 and published in the September-October 1924 American Chess Bulletin (page 162), Capablanca announced:

‘Dr Lasker’s victory [at New York, 1924] forces me to change my intentions for the time being at least. Were I to retire, the championship would revert to Dr Lasker and the old situation would again obtain, which, to my mind, is not desirable. I must, therefore, remain in the saddle.’

José Raúl Capablanca

See also pages 261-262 of Chess Explorations.

On page 231 of the October-November 1981 CHESS Euwe stated, in an interview:

‘In 1933, though an accepted grandmaster, I was thinking of giving up chess.’

Reuben Fine’s withdrawal from serious chess in the late 1940s is well known, and C.N. 6090 gave an exact source for a familiar quip on the subject:

‘When Fine switched his major interest from chess to psychoanalysis, the result was a loss for chess – and a draw, at best, for psychoanalysis.’

Those words were written by Gilbert Cant in an article ‘Why They Play: The Psychology of Chess’ on pages 44-45 of Time, 4 September 1972.

Concerning retirement plans, an earlier instance in Fine’s career was referred to in C.N. 5021 by Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina):

‘Page 282 of Chess Review, December 1938, quotes an interview given by Reuben Fine to Savielly Tartakower that had appeared in De Telegraaf. One passage reads:

“Earlier this year he [Fine] had decided to give up chess as a profession and complete his studies in mathematics. Last May he had asked the AVRO committee to release him, but was forced to live up to his contractual agreement to play.”’

In a letter sent from London on 23 July 1854 (i.e. four years before his match with Morphy) Harrwitz wrote:

‘Chess, if it has not been otherwise profitable, has procured me many a dear friend, but now my career is closed – I have ascended the ladder, and will not condescend to redescend it – so I give up chess altogether, go home and settle down into obscurity, which, if less conducive to renown and glory, is a great deal more so to health. When ambition is satisfied we look for something more solid and enduring. After years of indisposition and labour, I have at last discovered that I am “paying too much for my whistle”.’

Source: BCM, May 1884, page 182.

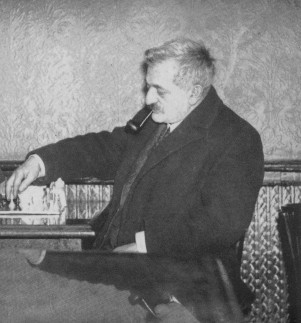

Daniel Harrwitz

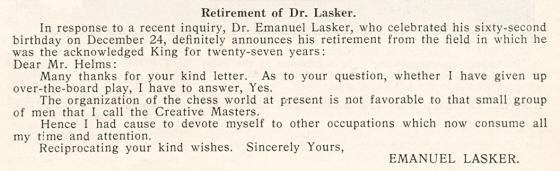

This text appeared on page 23 of the February 1931 American Chess Bulletin:

See too pages 105 and 261 of Chess Explorations.

C.N. 48 mentioned an unexpected report on page 12 of the Daily Sketch (London) of 23 December 1909 that Frank Marshall was retiring from chess. The full text was given in C.N. 6168, and the relevant parts are quoted below:

‘After a career extending over 21 years, Frank J. Marshall, the famous American chessplayer, has retired from the game. He retires with the title of champion chessplayer of America, which distinction he won recently from J.W. Showalter in Louisville.

... Marshall’s retirement is due to two reasons – his wife and his business. The former seems to be the greater cause, for she claims that her husband should devote his time to her and to their little son, Frank Rice Marshall.

When asked for his reasons for retirement Marshall said: “The game is too absorbing. To play it one must devote to it all of his time. No game in the world calls for such deep study and devotion as chess, and while I love it there are other things which must occupy my attention. I have private business responsibilities which suffer from the game, so I decided to quit playing for good.”’

C.N. 6168 asked for more details and cited a brief announcement which had appeared in the New York Times of 28 November 1909 (sporting news section, page S1):

‘Lexington, Ky., Nov. 27. – Frank J. Marshall of New York City, who yesterday won the chess championship of the United States over J.W. Showalter of Georgetown, Ky, authorizes the statement that he has quit the chess game for good and that he will give his attention to his business interests. He made this statement here today, upon coming from Georgetown, where his series with Mr Showalter ended last night ...’

A quote from the November 1901 BCM, page 448 was given in C.N. 1134:

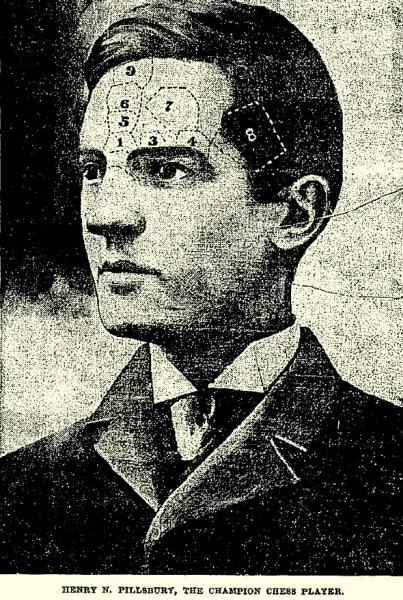

‘Mr Pillsbury writes that he intends to sail about 4 January for Europe, and will probably be away 18 months. During that time he will participate in all international tournaments (including, of course, Monte Carlo), and give exhibitions of blindfold chess, and very likely arrange a match with Dr Lasker. At the end of that time he will give up chess as a profession, and take to that of law. The Stratégie doubts whether he will be able permanently to leave his first love, and so do we. Dr Lasker is remarkably reticent with regard to any match between himself and Pillsbury, but, we believe, has made an informal acknowledgement of the challenge.’

This illustration, given in C.N. 5761, appeared in The Phrenological Journal and Science of Health, July 1900.

As quoted in C.N. 1215, on page 359 of the December 1891 International Chess Magazine Steinitz wrote:

‘... I beg to state that I shall most probably adhere to my intention of retiring from active play altogether, but I do not wish to stand pledged either way.’

C.N. 4160 added a passage from page ix of The Games of the St Petersburg Tournament 1895-96 by J. Mason and W.H.K. Pollock (Leeds, 1896):

‘Steinitz himself, in the Figaro, so far back as 1878 – when he was contemplating retiring from chess – claims that his record was then better than Morphy’s, but left the question of genius an open one.’

Further details about these matters are still being sought.

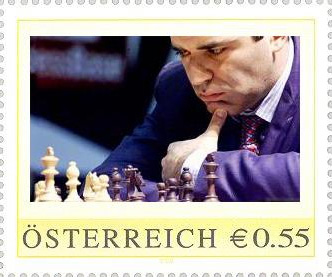

Garry Kasparov

Of course, there has been no more prominent announcement of retirement than Kasparov’s in March 2005. At the time, C.N. 3648 offered some reflections on a number of aspects of his chess career.

The above article originally appeared at ChessBase.com.

G.H. Diggle wrote on pages 635-636 of the December 1980 BCM:

‘… [in 1865] Staunton (over a decade after his retirement from the Chess Player’s Chronicle and a quarter of a century after launching the magazine) suddenly reappeared as Editor of a new periodical – the Chess World. But both the actual “Chess World” and Staunton himself had aged since he brought out his first number of the Chronicle. Then he was a young and adventurous pioneer, the hero of adventurous followers – now, a long deposed and ailing monarch. Though actually only 55 years old, his heart trouble frequently forced him to lay aside his pen; and the frustration caused by his physical state being no longer able to cope with the demands of his vigorous intellect had turned him into something very like Henry VIII in his last phase. While he could still comment on occasion with shrewdness and penetration on the chess affairs of the day (in particular the Steinitz-Anderssen match of 1866) he became more and more caustic and unfair to the younger generation, both in the Chess World and his weekly Illustrated London News column.’

(2891)

On the subject of Emanuel Lasker, below is C.N. 3736:

Page 102 of the September-October 1937 American Chess Bulletin transcribed a radio broadcast (Station WYNC, New York City) by Hermann Helms. A brief extract is given below:

‘The courage of the man is downright amazing, so I was moved to ask: “Doctor, do you ever intend to retire?”

To which he replied with a smile: “No; at any rate not until I have succeeded in gaining a competence from chess.”

He gave me a wink, as he said it, for you must know that the pursuit of chess professionally is not exactly a producer of wealth in large figures.’

Emanuel Lasker

Alfred Kreymborg’s claim to have retired is related in C.N. 1744 (see pages 135-136 of Chess Explorations and Alfred Kreymborg and Chess).

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.