Edward Winter

See C.N. 7323 below.

***

A recent re-reading, with increased enjoyment, of Achieving the Aim by Mikhail Botvinnik (Oxford, 1981) leads us to the conclusion that it is one of the greatest chess autobiographies ever written. Here are a few choice Botvinnik quotations:

‘Capablanca’s calm style, the harmonic combination of very exact positional understanding with a calculation of variations, imparted a particular elegance to the Cuban’s games. With Capa all the pieces played together, they were firmly linked. Capablanca was equally strong in complex and simple positions.’ (page 90)

‘As a player Keres had failings which were well known to me. The first was his slight uncertainty when he had to orientate himself in new opening schemes. He preferred on the whole obsolete opening systems. That was why he had a taste for open play. His second failing, a psychological one, was a tendency to fade somewhat at decisive moments in the struggle, while when his mood was spoiled he played below his capabilities.’ (page 110)

‘Reshevsky is what was once called a Naturspieler, an original player, but limited in his understanding of chess, insufficiently universal.’ (page 119)

‘It is clear now to many people that Fischer has a maniacal fear of beginning a competition.’ (page 198)

‘Euwe is a complex character. A talented and sharp person, lively and kind, but when he was head of FIDE, as at the chess board, he was insufficiently principled in his presidential actions.’ (page 202)

(442)

An endnote on page 271 of Chess Explorations reported that C.N. 21 had quoted Botvinnik’s description of himself on page 178 of Achieving the Aim:

‘A Jew by blood, a Russian by culture, Soviet by upbringing.’

From Anthony Saidy (Santa Monica, CA, USA):

‘One must exercise caution in interpreting anything of provenance from the “land of the censor”, including the internal mental censor of every Soviet citizen. What struck me about Botvinnik’s Achieving the Aim is its relative frankness. While gleaning the favor of the author’s personality requires patience, what finally emerges is a man of supreme self-confidence, an outward conformist who drops but an occasional hint of criticism of the system, a somewhat paranoid fellow who has a bad word for nearly every colleague or rival of the last half-century. I suppose one should be grateful for crumbs, like mention of anti-Semitism. But don’t expect a disclosure, à la Shostakovich’s posthumous Memoirs, of any of the anguish of living under the monster Stalin, who received such an adulatory cable from the author from Nottingham in 1936. One is free to interpret – does his mention of Akhsharumova mean a protest against the persecution of her and her husband Gulko, still deprived of visas to emigrate? Our Nixon gang coined an applicable phrase – “modified limited hang-out”.

Allied comments: the omission of the great Herbstman from Zelepukin’s 1982 Dictionary of Chess Composition is scandalous but typical; that octogenarian made the mistake of emigrating to Sweden and dying there. (By the way, Herbstman wrote the first psychoanalytic monograph on chess, in 1925. I have an English translation, provided by Dr N. Reider.) If one is paranoid enough, one can read something into the omission, from the 1979 second edition of Verkhovsky’s Nichya! (draw), of Tal’s 1972 preface and only one game – that of émigré Spassky.

Moreover, the hegemonic era of Karpov, the bureaucratic idol, is a moral and artistic miasma. One can debate his culpability in the persecution of Korchnoi’s family, but is it too much to ask that 64, which he edits, include the names of Alburt, Ivanov, Kushnir and Lemachko in the official FIDE list of the world’s highest-rated players? (Of these, three are defectors and one, Alla Kushnir, emigrated to Israel and strangely, after twice challenging for the women’s world title, disappeared from competition.

The Karpov personality cult does not spare not spare Geller’s Victory in Merano. How can Karpov’s 13 Ne4 be the “theoretical novelty of the year” in game 14, when he abandoned it four games later in favour of 13 a4! - ? Tal’s punctuations in 64 of the moves of the Baguio match can be proved biased by a mathematical formula of mine; simplified, it means that the result of a correctly punctuated game determines the preponderance of punctuation marks for each side. If Karpov makes several “!” moves in a game to Korchnoi’s none, how can Korchnoi win or draw?

In tendering the above comments, I am not politicizing chess, I am fighting its politicization.’

(493)

The translator of Achieving the Aim was Bernard Cafferty.

See also Mikhail Tal (1936-92).

‘Botvinnik, like many of his countrymen, often handles the opening very poorly with White, in sharp contrast to the complicated and ingenious defenses he frequently thinks up with Black.’

Source: Reuben Fine: Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958), page 83.

(593)

An endnote on page 271 of Chess Explorations:

C.N. 551 quoted Botvinnik in the context of Euwe’s death in 1981:

‘The world champions die in the strict order of their succession to the title. Thus the writer of these lines is the next on the list. I telephoned Smyslov and reminded him that after me it would be his turn. Smyslov laughed; indeed, as long as I am alive he can afford to laugh!’

Source: Europe Echecs, April 1983, page 13.

The following year C.N. 820 reported that Petrosian had died, out of sequence. Tal died in 1992 and Botvinnik in 1995.

The March 1984 Chess Life has an interesting interview with Botvinnik. The former world champion was first asked to nominate ‘the greatest chess book’. His reply was, ‘Without question, Chess Fundamentals by Capablanca. It’s still timely and has value to players of all levels.’ Later Botvinnik was asked who out of Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine had the deepest understanding of chess. Botvinnik’s view: ‘I think Capablanca had the greatest natural talent. When a great pianist plays, we don’t hear separate notes, but we hear a musical picture. So too, Capablanca didn’t make separate moves – he was creating a chess picture. Nobody could compare with him in this.’

(689)

The highlight of issue zero of the magazine New in Chess is a most extraordinary interview with Botvinnik. Our eye homed in on a quote, ‘Capablanca was a genius, the greatest genius in the whole history of chess’, and we at once felt well disposed to the former world champion, ‘Mr Soviet Chess’. But the rest of the material makes Botvinnik a difficult man to like, the interview being a supreme example of high bitchery.

Karpov is ‘an exploiter of other people’s ideas. His ability to use these ideas is not at issue, but he himself is about as fertile as a woman who has been sterilized’. Portisch and Polugayevsky ‘have no talent for real research’. Balashov ‘is dull-witted. When he comes into unknown territory he is as defenseless as a kitten’. Karpov ‘cannot just force Roshal, who writes all his books for him, to develop a new chess idea for him’. Kasparov’s games ‘are the only ones I still play over’. ‘I hardly talk to the grandmasters here anymore. Nor to the Chess Federation of the USSR.’

The magazine quotes Spassky’s reaction: ‘It is typical of Botvinnik, that he wants to destroy chess, after giving up his own career as an active chess player.’

Certainly Botvinnik adopts a most surprising anti-Soviet stance, and even makes a point of mentioning the dreaded Korchnoi: ‘Of the top chess players of the moment I would like to mention two names: Korchnoi and Kasparov.’ He even permits himself an analysis of Karpov’s divorce: ‘It was not a real divorce. She just left him. When two people are not in love they separate automatically.’

Up until a few years ago Botvinnik was a dull case for historians, psychologists, etc., but his recent writings and interviews reveal an unknown, or neglected, side of his character. The interview is an amazing document, and a memorable scoop for New in Chess. News indeed.

(825)

The full text of C.N. 825 is given in Chess Jottings.

‘As far as Garik [Kasparov] was concerned, I immediately came to blows with him. For he first made a move and only then thought about it. While the proper order is, as you know, exactly the other way around. “Watch out”, I used to say to him, “if you go on like this you’ll become a Taimanov or a Larsen, Garik.” These two were the same, even when they were grandmasters – first move, then think.’

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) quotes the above remark by Botvinnik from page 40 of the 0/1984 issue of New in Chess (in a feature, ‘Botvinnik speaks out’, on pages 36-43).

(8192)

On page 39 of 15 Games & Their Stories Botvinnik ponders whether he acted correctly in a game against Reshevsky by not telling his opponent that the latter had forgotten to press his clock, and concludes that most likely he did the right thing by saying nothing. Yet on page 68 Botvinnik himself is to be found forgetting to stop his clock and he remarks that ‘the portion of the Chess Codex forbidding the referee from drawing the player’s attention to a possible time-forfeit was in need of revision’.

(727)

Some comments by Botvinnik, from the Pergamon book Half a Century of Chess:

Page 65. ‘In 1935 my game with Chekhover made such a deep impression, that there were some “specialists” who maintained that it was prepared beforehand! Even assuming that I could have been under suspicion, would that have been fair to that honest man Vitaly Chekhover?’

Page 72. ‘Having learned to play chess rather late (at the age of 12), in later years I often committed “infantile” mistakes.’

Page 83. On Levenfish: ‘His endgame play was extraordinarily deep.’

Page 94. On his brilliant 30 Ba3 v Capablanca at AVRO, 1938: ‘The beginning of a 12-move combination, including the following winning manoeuvre. I must admit that I could not calculate it right to the end and operated in two stages. First I evaluated the position after six moves and convinced myself that I had a draw by perpetual check. Then after the first six moves I calculated the rest to the end. A chessplayer’s resources, particularly at the end of a game, are limited.’ (Interesting, since annotators have stated that Botvinnik had foreseen everything.)

Page 109. Keres: ‘During the period from 1936 to 1975 he was probably the strongest tournament player.’

Page 110. ‘I was always underestimated as a master of attack.’

Page 113. Smyslov: ‘For five years, between 1953 and 1958, he was unbeatable.’

Page 240. ‘Fischer’s character was always clearly inadequate ... [After 1962] Fischer achieved outstanding successes, but illness would seem to have torn him away from chess, which is very, very regrettable: the chess world has suffered an irreparable loss.’

(863)

Long Calculation notes that on page 174 of The Golden Dozen (Oxford, 1976) Irving Chernev wrote regarding Botvinnik v Chekhover, Moscow, 1935:

‘The longest combination ever seen in master play is this 22-mover by Botvinnik.’

Carl-Eric Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) sends the following list from Ståhlberg’s I kamp med världseliten (Örebro, 1958), page 70:

‘My hardest opponents: Alekhine and Botvinnik; my most interesting opponent: Lasker; my most pleasant opponent: Keres; the greatest master: Alekhine; the greatest talent: Capablanca; the greatest strategist: Botvinnik; the greatest tactician: Lasker; the foremost endgame practitioner: Smyslov; the most imaginative master: Bronstein.’

The September 1977 Chess Life & Review (pages 491-492) has an article by Frank Brady on the Capablanca-Botvinnik simul game of 1925 (‘an extract from Frank Brady’s Soviet Master, a biography of Dr Mikhail Botvinnik, to be published in 1978’ – what has happened?). We read:

‘At the rustic Leningrad airstrip the same day, Capablanca was ready to depart for Moscow to resume play in the international tournament. A chess journalist, Yakov Rokhlin, was seeing him off, and as the two men stood in the long, drafty airfield building, Capablanca talked about the previous night’s exhibition: “What a boy that was there. The one in the spectacles. He played a good game, calm and accurate. He’ll be a master some day.”’

Really? Capablanca, we thought, was at the railway station at the time.

(979)

Regarding the first paragraph above, Frank Brady (New York, NY, USA) informs us:

‘I had been in correspondence with Yakov Estrin in the early 1970s about penning a biography of Botvinnik and had received a positive response of interest. While in Iceland during the 1972 match I wrote to Botvinnik requesting a meeting in Macedonia during the Olympiad. He granted the request, and we met with Albéric O’Kelly de Galway as an interpreter. It was a fascinating meeting, but we could not come to terms about my becoming Botvinnik’s biographer.

Several years later, Burt Hochberg, who was the chess consultant for David McKay Co., asked if I would be interested in writing about Botvinnik, and although it looked like it would happen I never received a contract, for reasons unknown. I assume that is the book “Soviet Master” referred to.’

(11956)

Of Botvinnik: ‘His endgame play probably netted him more points per game played than anyone else.’ Chess Gazette (insert to issue 42).

P.C. Wood (Hastings, England) raises the question of where Botvinnik was born. In Part I of Baturinsky’s work on the former world champion, as well as in Flohr’s contribution to Hans Müller’s book Botwinnik lehrt Schach, it is stated that he was born in Kuokkala (now called Repino) near St Petersburg. Flohr added that at the time Kuokkala belonged to Finland. Why, then, do most writers (such as Müller himself, nine pages further on ...) give only ‘St Petersburg’? Mr Wood, who suspects that in Achieving the Aim Botvinnik deliberately avoiding talking about his life up to 1920, asks whether Botvinnik himself ever made a direct statement about his place of birth.

(1350)

Mr Wood has now noted that Botvinnik has made a direct statement on his birth, on page 8 of the Weltgeschichte des Schachs volume devoted to his games. It confirms the details given by Müller.

(1447)

From Ed Tassinari (Scarsdale, NY, USA):

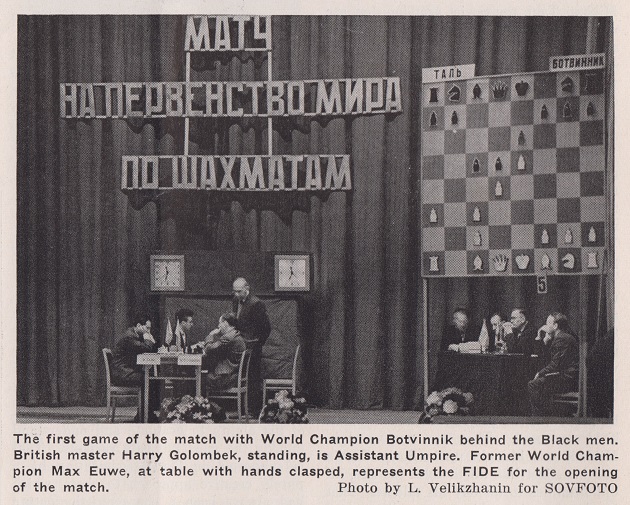

‘On page 182 of the 1962 World Book Year Book (the annual supplement to the World Book Encyclopedia and a review of the events of 1961), the following can be found, written by Theodore O’Leary:

“Mikhail Botvinnik, 49 year old Russian engineer, recaptured his world chess title at the international masters’ tournament held in May in Bled, Yugoslavia. Botvinnik defeated the 24 year old Mikhail Tal of Latvia, who had snapped the Russian’s 12 year victory streak the year before.

Runner-up at Bled was 18 year old Bobby Fischer ... He also beat Tal at the Bled matches, but came in second to Botvinnik because of draws with lesser players.”’

(1664)

Harald E. Balló (Essen, Germany) draws attention to the episode related in Lilienthal’s autobiography, a German edition of which was published in 1988. Lilienthal records (page 67 of the German edition) that before the last round of Hastings, 1934-35 he was in a position to share 4th and 5th places with Capablanca if the Cuban won his game against Botvinnik. In a slightly worse position, Botvinnik offered Capablanca a draw, but the latter said he would accept only if Lilienthal agreed. Botvinnik’s friend and second, Weinstein, therefore took a taxi to the hotel to seek Lilienthal’s ‘permission’. Lilienthal returned to the playing room, thanked Capablanca for his sportsmanship and agreed to the draw. And so Lilienthal shared 5th-6th places instead of the 4th-5th he would have shared had the Cuban won.

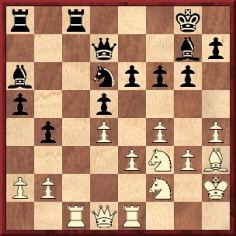

We would comment that, as is often the case, scrutiny of the contemporary record creates complications. Firstly, the leading scores before the final round were: Thomas: 6½. Euwe: 6. Flohr: 5½. Capablanca: 5. Botvinnik: 4½. Lilienthal: 4½. The February 1935 BCM (page 57) remarks that ‘a 26 to 1 chance had to come off in this [the final] round to bring about a triple tie. Thomas had to lose, Euwe had to draw and Flohr to win; and it was so.’ If Capablanca had beaten Botvinnik he would have finished clear fourth with 6 points even if Lilienthal had won instead of drawing his last-round game against Menchik. With the Cuban only drawing, Lilienthal could have finished level with him, ahead of Botvinnik, if he had defeated Menchik. In fact, their game (with Lilienthal as White) was drawn, to the surprise of some, after 38 moves in the following position (White to move):

(1904)

It is odd to think of Botvinnik losing a 19-move Evans Gambit but such a game has been published.

Ilya Ibramovich Kan – Mikhail Moseevich Botvinnik

USSR Championship (semi-final section), Odessa, 12 September

1929

Evans Gambit Declined

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bb6 5 a4 a6 6 Nc3 Nf6 7 Nd5 Nxe4 8 O-O O-O 9 d3 Nf6 10 Bg5 d6 11 Nd2 Bg4 12 Bxf6 Qc8 13 Nxb6 cxb6 14 f3 Be6 15 Bh4 Nxb4 16 Be7 Qc5+ 17 Kh1 Rfe8 18 Ne4 Qc6 19 Bxd6 Resigns.

Source: Ajedrez, January 1930, page 12.

(2094)

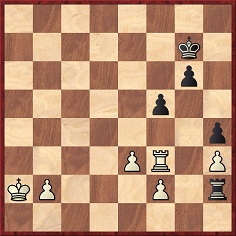

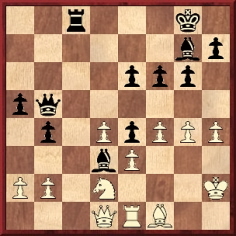

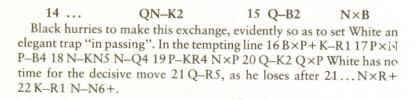

Jorge Luis Fernández (Mendoza, Argentina) queries the analysis on page 401 of Botvinnik’s Partidas Selectas, volume 3: (Madrid, 1992)

Mikhail Botvinnik-Duncan Suttles, Belgrade, 1969

White to move

Botvinnik writes that instead of 25 Rf3 he should have played 25 b3!! and if 25...Rxe4 26 Rxe4 Bxf1 White wins easily by 27 Ne6+ Kg8 28 Qb2 Ne5 29 Rxe5 dxe5 30 Qxe5 Rc7 31 Qxc7.

However, our correspondent suggests that 30...Kf7 would at least draw.

Similar analysis by Botvinnik appeared on page 323 of his book Analiticheskiye I Kriticheskiye Raboti 1957-1970 (Moscow, 1986), where he attributes the line to the Bulgarian master Tringov. The Spanish book does not mention Tringov by name, thereby giving the impression that the ‘Bulgarian master’ was Suttles, who is Canadian. Botvinnik gave different analysis on page 194 of Selected Games 1967-1970 (Oxford, 1981).

From page 395 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

‘By not winning the title I have put a shadow on my chess career and it is a little sad that I have had to read and hear for more than 40 years that I am not a good player. It seems that all my other achievements in chess have been ignored.’

David Bronstein on page 108 of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, which he co-authored with Tom Fürstenberg (London, 1995).

(2251)

From page 11 of Uncompromising Chess by Alexander Belyavsky (London, 1998):

‘In contrast to the wonderful books of previous World Champions, in my opinion the three-volume set of Botvinnik’s games is the first systemized work capable of giving a player a grandmaster understanding of the game. Botvinnik’s commentaries are so instructive, that for anyone wishing to become a grandmaster, I would recommend that in the first place they should study his works.’

(2254)

A paragraph from our article on World Champion Combinations by Raymond Keene and Eric Schiller (New York, 1998):

Keene and Schiller report that Euwe dethroned Alekhine in 1937; everybody else believes that Euwe won the title in 1935 and lost it in 1937. Page 119 erroneously declares that Botvinnik won the 1954 world championship match against Smyslov. The first page of the Botvinnik chapter says: ‘Beating Capablanca was an achievement that every World Champion in the first half of the 20th century achieved, and Botvinnik was the last of a long line to do so …’. (Let’s pause here to admire the polished prose style: ‘an achievement … achieved’.) In reality, of course, the ‘long line’ consisted of just four champions, and the last of those victories was by Euwe, not Botvinnik. Regarding the famous game Botvinnik-Capablanca, AVRO, 1938, page 101 affirms after 34 e7, ‘Of course Botvinnik had to see that there was no perpetual check when he played 30 Ba3’. That is flatly disproved by Botvinnik’s own annotations on pages 92-94 of Half a Century of Chess; after 30 Ba3 he wrote: ‘I must admit that I could not calculate it right to the end and operated in two stages. First I evaluated the position after six moves and convinced myself that I had a draw by perpetual check. Then after the first six moves I calculated the rest to the end.’

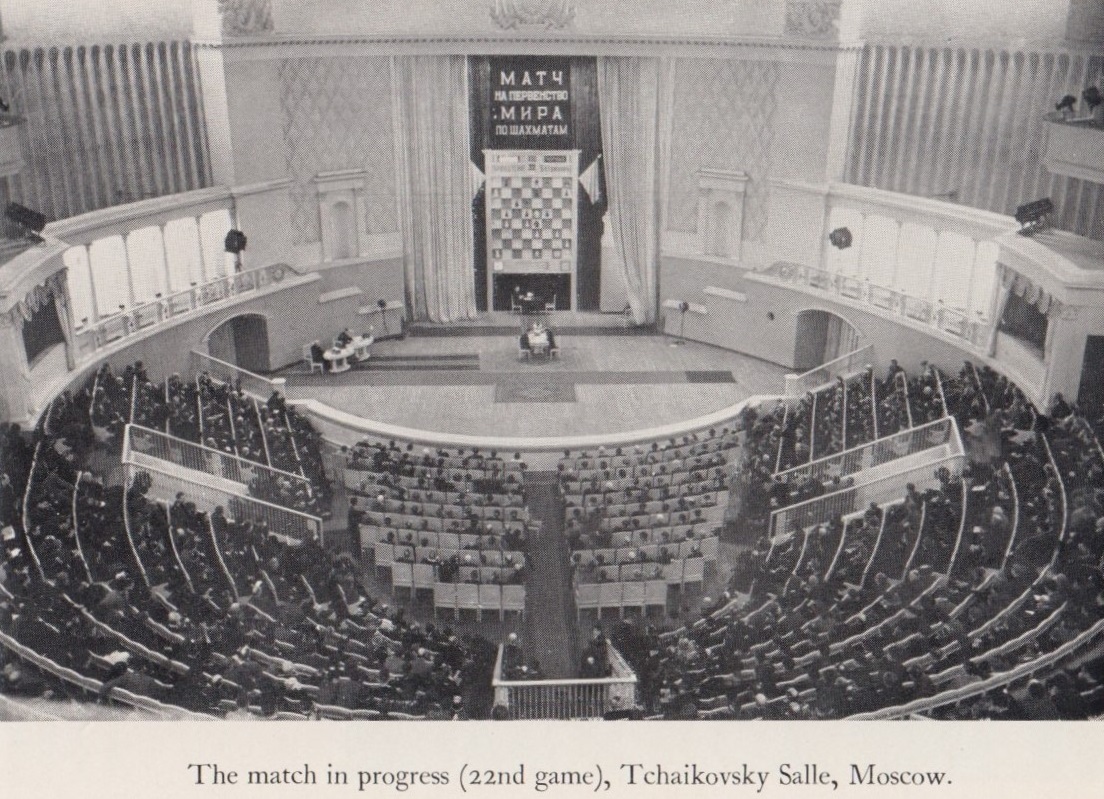

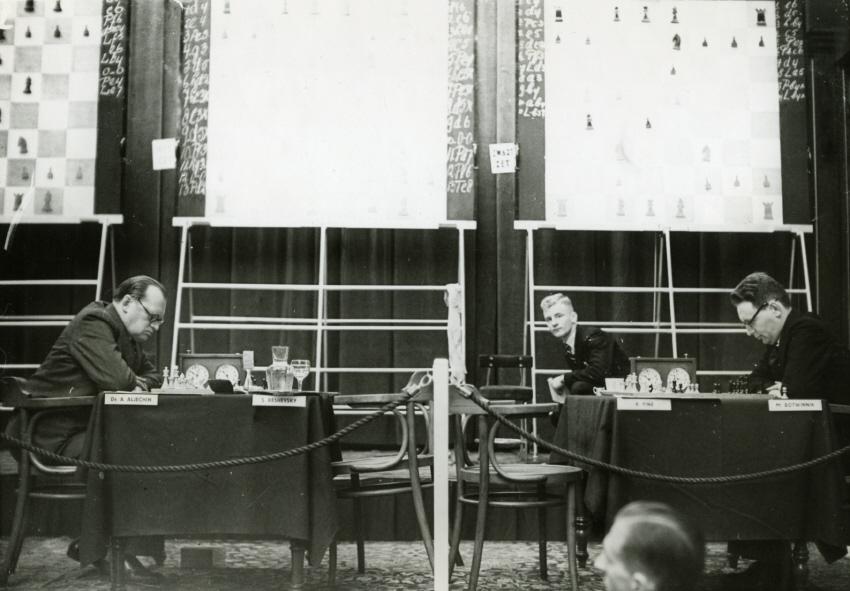

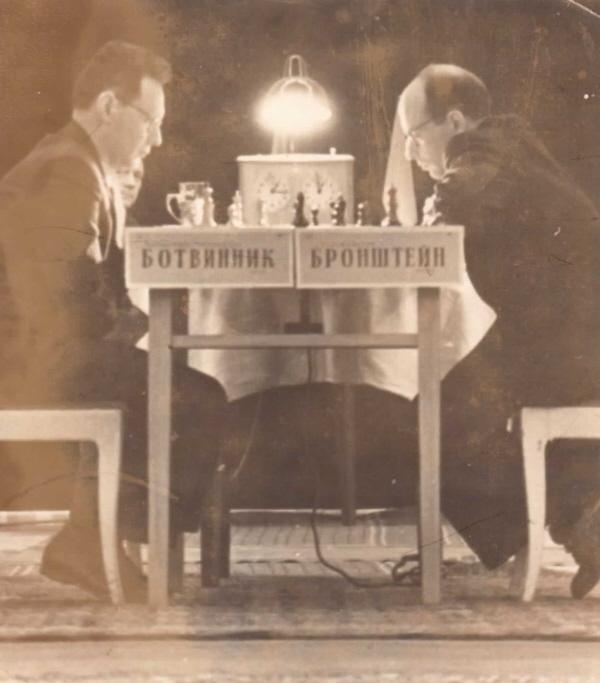

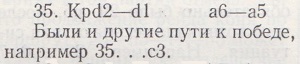

Photograph opposite page 54 of The World Chess Championship: 1951 Botvinnik v Bronstein by William Winter and R.G. Wade (London, 1951)

Which defeated world champion claimed that a prerequisite for success in top-level chess is a sense of humour?

The rather surprising answer is Botvinnik, in a statement dated 3 May 1957, i.e. shortly after he lost his world title to Smyslov. He wrote that despite the defeat he had ‘still tried not to lose the sense of humour that is so essential both for the struggle and for victory in this field’.

Source: World Chess Championship 1957 by H. Golombek, page 139.

(2445)

Alessandro Nizzola (Mantova, Italy) draws attention to a comment by Tony Miles quoted on page 6 of How to Get Better At Chess: Chess Masters on Their Art by L. Evans, J. Silman and B. Roberts (Los Angeles, 1991):

‘Perhaps the most important trait a player needs to become successful is a warped sense of humor.’

(2477)

As noted on page 393 of A Chess Omnibus, before publishing C.N. 2477 we checked with Tony Miles that he had indeed made the remark.

C.N.s 2545 and 7819 quoted a remark on page 271 of C.J.S. Purdy’s The Australasian Chess Review, 31 October 1938:

‘We consider Botvinnik the most brilliantly searching annotator in the world – the ordinary junk written by annotators doesn’t go down in Russia, where there are thousands who can pull bad notes to pieces.’

From page 160 of a book by Gabriel Mario Gómez, Historia del ajedrez (Buenos Aires, 1998):

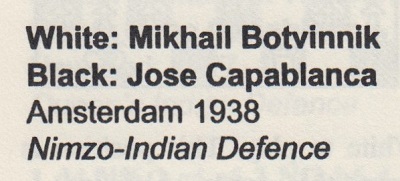

(2765)

For many other instances, see Chess: Mistaken Identity.

‘Botvinnik-Capablanca, Amsterdam 1938’ is the game heading in Jewish Chess Masters on Stamps by F. Berkovich (Jefferson, 2000), page 108, i.e. in the section written by N. Divinsky. It is an elementary mistake, commonly seen. Botvinnik’s famous brilliancy was played (on 22 November 1938) in Rotterdam, as is recorded by many contemporary sources (e.g. page 106 of Euwe’s book on the tournament).

The bibliography of the Berkovich book (page 132) contains some improbable references, such as items purportedly written by L. Shamkovich and D. Spanier in 1935 and 1934 respectively.

(2976)

As shown in C.N. 10413 the classic Botvinnik v Capablanca game in the AVRO, 1938 tournament was played on 22 November 1938 in Rotterdam. However:

The Sunday Times Book of Chess by R. Keene (Aylesbeare, 2005), page 30

Mikhail Botvinnik by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 2014), page 111.

See too Cuttings.

From page 272 of Chess Explorations:

On page 242 of the June 1979 CHESS we published Emanuel Lasker v Powell, simultaneous exhibition, Liverpool, 1895, a game which saw play similar to Botvinnik’s against Capablanca [AVRO, 1938]. Lasker too offered the sacrifice Bb2-a3 with the aim of diverting the enemy queen, which was blocking a white passed pawn at e6.

Although the exercise may be glib space-filling, chess authors often write portentously about the alleged influence of a given master on a leading figure from a later generation, and over the years such ‘connections’ have been constructed (or fabricated) between all kinds of players. Two passages concerning Botvinnik in relation to a) Nimzowitsch and b) Staunton are presented here, without further comment. The first comes from page 229 of The Great Chess Masters and Their Games by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1960). Having approvingly quoted some remarks on Botvinnik by Harry Golombek (who did not mention Nimzowitsch), Reinfeld observed:

‘What we learn from this authoritative estimate is that Botvinnik’s style is modeled on the games of Nimzowitsch rather than those of Chigorin. The specialized opening repertoire, the “new and baffling moves”, the hidden dynamism of seemingly harmless ideas, the “delayed vehemence”, the “subtle and deeply refined endgame play” – all these point to Nimzowitsch’s influence.

This impression is strengthened when we recall that Botvinnik’s formative years – 1925-1931 – coincided with the period of Nimzowitsch’s most impressive victories and the publication of his two famous works, My System and Chess Praxis.

One characteristic Nimzowitsch element is missing in Botvinnik’s play to be sure: the older master’s love for bizarre, mysterious, provocative moves. But this is understandable, for such eccentricities are wholly foreign to Botvinnik’s sobriety and self-critical temperament. And we may see here also the counter-influence of Alekhine, who always insisted that his finest flights of imagination had a logical, common-sense basis. Alekhine was often at pains to demonstrate that his occasionally paradoxical or otherwise highly original moves were in no way grotesque – that they evolved naturally out of the needs of a given position. But after all, Botvinnik is Botvinnik, and whatever he absorbed from Nimzowitsch and Alekhine he transformed into his own personal approach to the game.’

The second case creates a connection between Botvinnik and Staunton and was, at the time, a rare example of the Englishman being lauded beyond his homeland. The text comes from page 137 of Les échecs dans le monde by Victor Kahn and Georges Renaud (Monaco, 1952):

‘Howard Staunton a été non seulement le précurseur de Steinitz et de son époque, mais encore il laisse pressentir le style actuel d’un Botvinnik. Il est regrettable que la gloire factice d’un Anderssen, porté au pinacle par ses compatriotes, ait fait oublier – tout au moins hors de la Grande-Bretagne où son traité se lisait encore avant la première [sic] guerre mondiale – la profondeur des conceptions du champion anglais, conceptions tout à fait surprenantes pour ce temps-là.

Mais Staunton, à son époque, était unique et il n’y avait pas, pour apprécier son style, un climat et un public.’

(3283)

Page 249 of the August 1948 CHESS stated:

‘We hear that Mikhail Botvinnik is the subject of a new Russian documentary film, World Champion.’

What more is known about it?

(3823)

The complexities of selecting a challenger in the late 1930s are discussed in World Championship Disorder.

Regarding FIDE’s efforts to organize a world championship match after Alekhine’s death in March 1946, see Interregnum, which includes these photographs:

Left to right: Max Euwe, Vassily Smyslov, Paul Keres, Mikhail Botvinnik, Samuel Reshevsky

Mikhail Botvinnik and Alexander Rueb (the FIDE President, 1924-49)

See also The World Chess Championship by Paul Keres, an article published in 1941, as well as Paul Keres (1916-75).

Capablanca Interviewed in 1939 gives the Cuban’s assessment of Botvinnik.

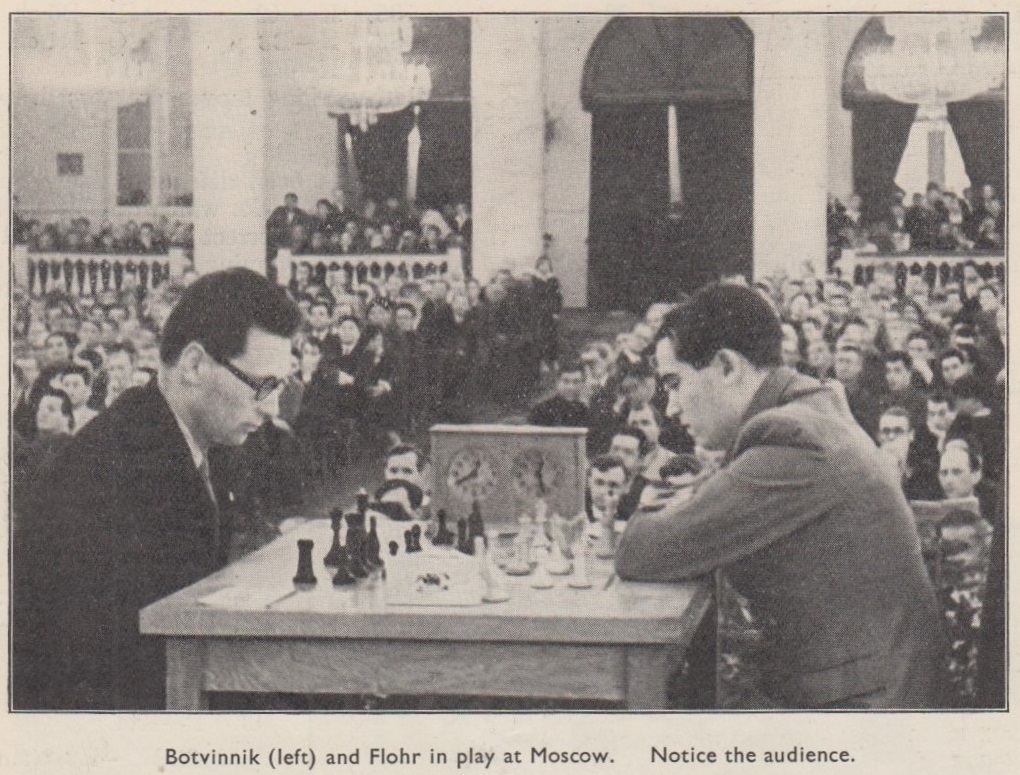

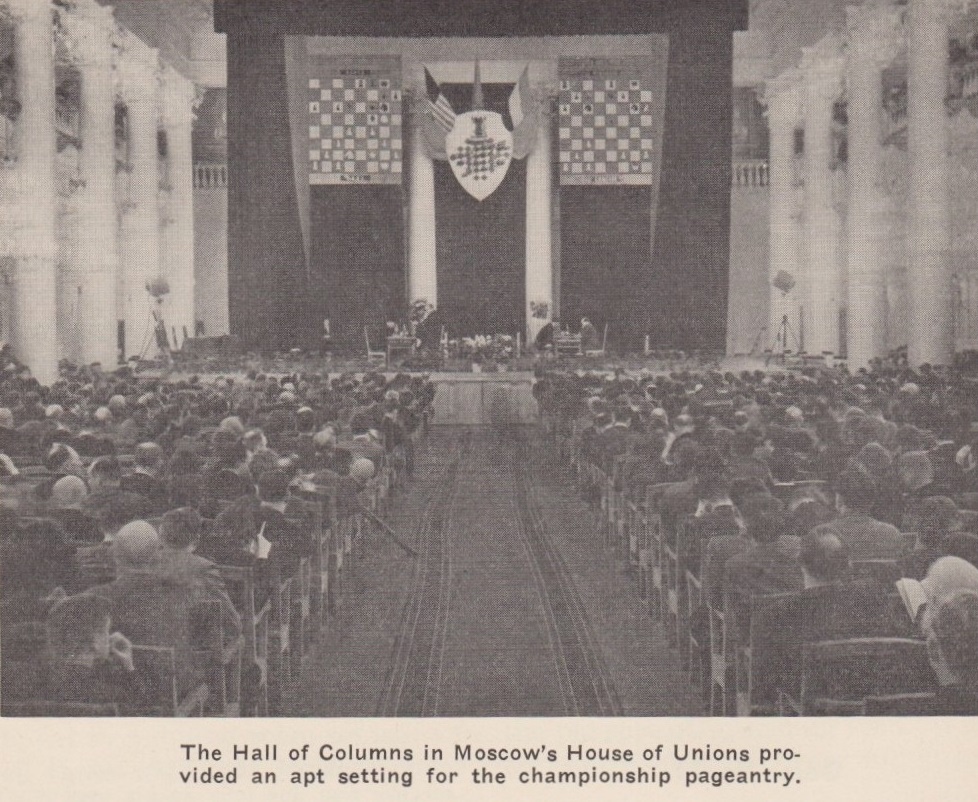

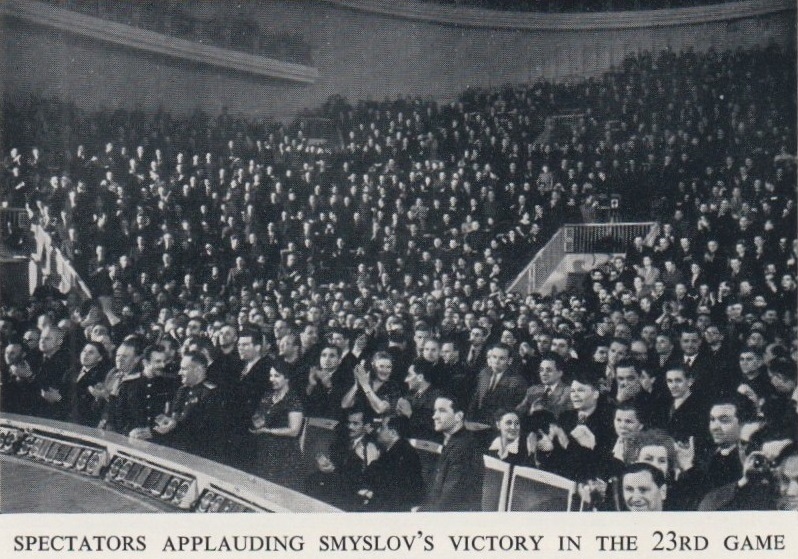

The photographs below come from Crowds at Chess Events.

From page 416 of CHESS, 14 July 1936:

The next picture is from page 74 of World Chessmasters in Battle Royal by I.A. Horowitz and Hans Kmoch (New York, 1949), a book on ‘the first world championship tourney’:

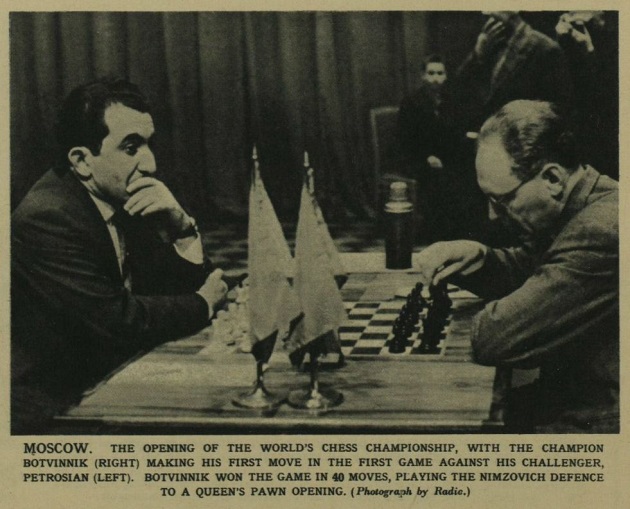

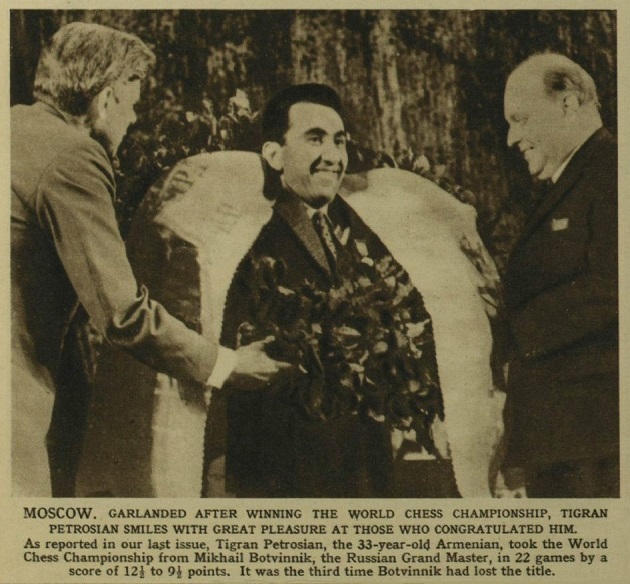

From opposite page 63 of World Chess Championship 1954 by H. Golombek (London, 1954):

The following passage from page 16 of C.H.O’D. Alexander’s A Book of Chess (London, 1973) is worth noting:

‘If you play Botvinnik, it is even alarming to see him write his move down. Slightly shortsighted, he stoops over his score sheet and devotes his entire attention to recording the move in the most beautifully clear script; one feels that an explosion would not distract him and that examined through a microscope not an irregularity would appear. When he wrote down 1...c2-c4 [sic] against me, I felt like resigning.’

We take the game in question to be Alexander v Botvinnik in the Amsterdam Olympiad of 1954, a Sicilian Defence.

(4292)

From page 102 of the 4/2009 New in Chess (in an article by Hans Ree):

‘... I was reminded of a remark about Botvinnik that is attributed to C.H.O’D. Alexander: “When he wrote down 1 c2-c4 against me I felt like resigning.” By the way, Botvinnik never played 1 c4 against Alexander (against me he did), so this might seem an instance of the threat being stronger than the execution, but only if you believe the impossible: that Botvinnik would ever write down a move that he was not going to play.’

This episode was discussed briefly in C.N. 4292, where Alexander’s exact words were quoted, from page 16 of A Book of Chess (London, 1973):

Reviewing the work on page 63 of the February 1974 BCM (the month Alexander died), A.J. Roycroft wrote:

‘... I shall content myself with wagering that what Botvinnik wrote on his scoresheet with such a degree of intimidating concentration that Alexander, as White, felt like resigning on the spot was not (page 16) “1...c2-c4” but 1...c7-c5.’

In C.N. 4294 we suggested that the contest in question was Alexander v Botvinnik, Amsterdam, 1954, but the players’ game at Nottingham, 1936, also a Sicilian Defence, is a no less plausible candidate. Alexander provided brief notes on page 59 of CHESS, 14 October 1936, but said nothing until move ten. Do his other writings shed any further light on the Botvinnik c4/c5 matter?

(6185)

See also C.N.s 6587, 6596 and 8138. A paragraph by Alexander quoted in C.N. 6596:

‘Botvinnik is in the greatest tradition of world champions, with Morphy, Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine. Playing him, one gets a strong sense of someone dedicated to the game – a mixture of monk and scientist. When I played Botvinnik in Amsterdam in 1954 I was temporarily demoralized by watching him write down his first move. Slightly short-sighted, he gave his entire attention to recording the move in the most beautifully clear and precise script; only after completing this to his entire satisfaction did he again bend his mind to the game. This calm but intense concentration on even the most trivial aspect of the game made me feel like a fly under the scientists’ microscope.’

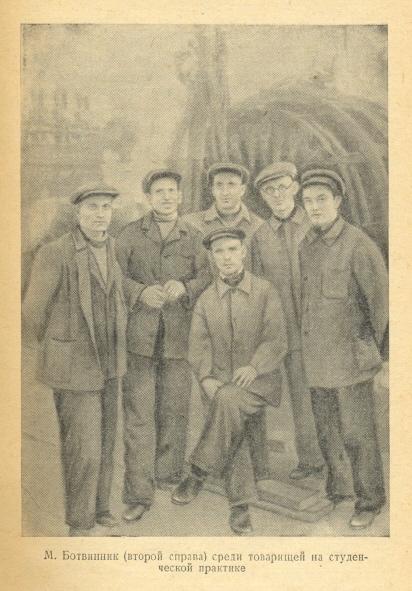

Mikhail Botvinnik is second from the right, alongside fellow students. The picture has been gleaned from page 19 of Mikhail Botvinnik by Kirill Levin (Moscow, 1951):

(4412)

At a dinner organized by the Spanish Chess Federation at the Casino de Madrid in December 1935 Capablanca was questioned about his rivals. The Alekhine v Euwe world championship match was then being played in the Netherlands, and the Cuban was guarded on that subject. As for the future, he believed that he himself had the greatest right to challenge for the world title, followed by Flohr (who had enjoyed much success in recent years) and Lasker (regarded by Capablanca as still in the first rank of champions, despite his age). The Cuban had very high praise for Botvinnik, whom he considered more likely to become world champion than such other young players as Lilienthal and Reshevsky. Finally, Capablanca spoke highly of Tartakower, saying that he was, when on form, one of the most redoubtable masters.

The report, published on pages 491-492 of the December 1935 issue of El Ajedrez Español, is given below:

‘En estas contestaciones estuvo reservado respecto al resultado del match Alekhine-Euwe; nos reafirmó en nuestro convencimiento de que en orden de derechos la posición de los candidatos al título mundial son: Capablanca, Flohr (cuyos éxitos en estos últimos años son indiscutibles y de gran valor, según el maestro cubano) y Lasker, quien a pesar de su edad todavía está en primera fila de campeones, a juicio de quien le desposeyó del título mundial. De Botvinnik (el campeón ruso), hace Capablanca magníficos elogios y lo considera con más condiciones para llegar al título máximo que otros jóvenes que se han revelado en los últimos años, como Lilienthal y Reshevsky. También hace elogios de Tartakower, al que estando en forma considera uno de los más temibles grandes maestros.’

(4577)

The conclusion to Fischer’s draw against Botvinnik at the Varna Olympiad in 1962 has also given rise to discussion, on a human level. On page 153 of Analiticheskiye I Kriticheskiye Raboti 1957-1970 (Moscow, 1986) Botvinnik reported that Fischer was distraught as he left the hall. To quote the English translation on page 183 of volume three of Botvinnik’s Best Games (Olomouc, 2001):

‘Only here, with his face [as] white as a sheet, did Fischer shake my hand, and with tears in his eyes he left the hall.’

The matter arose on page 137 of the September 1963 Chess World when C.J.S. Purdy was discussing Alexander Kotov:

‘I also knew that he was a very kindly writer. I have never known him to treat anyone unkindly in print. By contrast, his countryman Flohr, a clever journalist, handled Bobby Fischer almost spitefully, when he reported that after he had only succeeded in drawing with Botvinnik in Varna, after having a winning advantage, he left the room and, having reached the corridor, burst into tears. As Fischer probably thought he was alone by then, it was cruel to record such a thing, but Flohr knew it was good “copy”. Kotov would never initiate such a story. Nor would I myself; I am prepared to use it once it has been made public already, for I am not a censor, but I think Kotov is too kind even to do that ...

I do not decry Flohr. There is virtue in sheer truth. But Flohr could have written sympathetically or purely factually, without spiteful overtones.’

Can a reader quote Flohr’s exact words?

(4595)

See also Salo Flohr (1908-83).

Botvinnik was a notable absentee from Fischer’s selection of ‘the ten greatest masters in history’ (Chessworld, January-February 1964). The following explanation was on page 57:

‘In compiling this list of ten greatest Masters is history, Bobby Fischer (who in the editor’s opinion belongs on such a list himself) based his final selection on the games of the players he has named rather than on performances and credits earned – which could explain players like Lasker, Botvinnik, etc. not being mentioned. When queried on this point, Bobby replied: “Just because a man was a champion for many years does not necessarily mean that he was a great player – just as we wouldn’t necessarily call a ruler of a country ‘great’ merely because he was in power for a long time.”’

See also C.N. 5215 below (the choices of Chernev and Golombek).

The late David Bronstein seldom gave interviews, but a substantial one with Antonio Gude appeared on pages 38-42 of the March 1993 Revista Internacional de Ajedrez. Bronstein expressed irritation that he was remembered for his world championship match with Botvinnik and his book on the 1953 Candidates’ tournament. Asked whether he had been under pressure to lose the former event, he stated that, although there had not been direct pressure, circumstances related to his father, the fact that he was a Jew, and a clear institutional preference for Botvinnik had resulted in psychological pressure; Bronstein considered that winning the match could have been very damaging for him, although that did not mean that he had lost intentionally. For the record we quote the full exchange on this matter:

‘Gude: ¿Qué me dice del match con Botvinnik? ¿Le presionaron para que usted perdiera?

Bronstein: No hubo presión directa, naturalmente. Pero existían circunstancias, como mi padre, un manifiesto opositor al régimen, que había estado varios años en prisión, mi condición de judío, la marcada preferencia institucional por Botvinnik, a quien se le veía como un modelo soviético de campeón ... Había la presión psicológica del entorno, y a mí me parecía que ganar podría perjudicarme seriamente, lo cual no significa que yo perdiera de forma deliberada ...’

Bronstein spoke of the influence of his father, a rebellious defender of democracy. ‘From him I inherited that trait: when I am forbidden to do something, I rebel.’

(4753)

For the remainder of this item, see David Bronstein (1924-2006).

One of four photographs provided by Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England):

Alexander Alekhine and Mikhail Botvinnik, AVRO, Amsterdam, 6 November 1938

(4791)

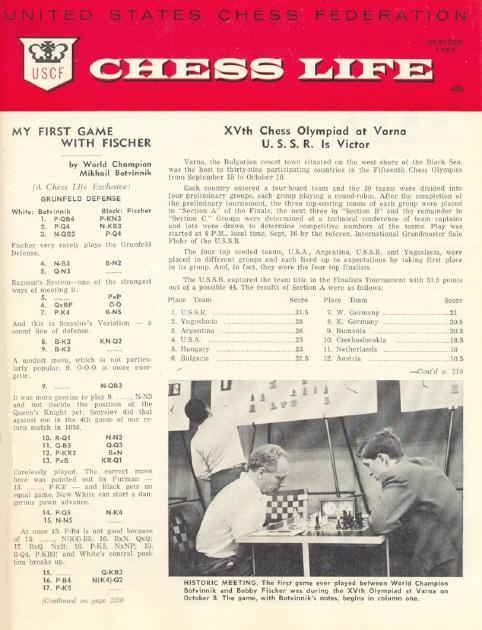

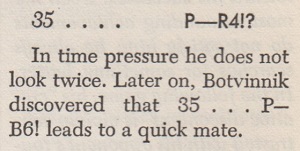

C.N. 4863 asked about the first occurrence in a chess context of the phrase often attributed to Botvinnik, ‘Every schoolboy knows that ...’.

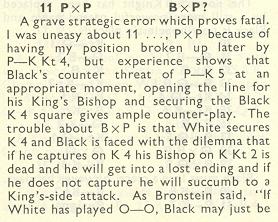

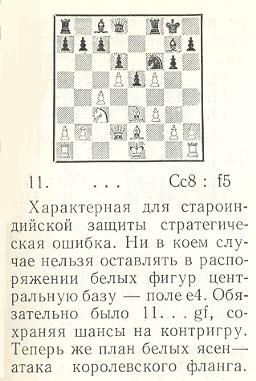

Taking up a lead from Norman Stephenson (Middlesbrough, England), who had a recollection of the remark in a UK chess magazine in relation to the game Botvinnik v Alexander, Munich Olympiad, 1958, we have found surprising passages in both CHESS and the BCM.

On page 30 of CHESS, 1 November 1958 P.H. Clarke wrote regarding round eight of the Olympiad finals:

‘England were beaten by the same margin as at Moscow [+0 =0 –4, as in the 1956 Olympiad]. Botvinnik won instructively.

All the Russians were horrified by Alexander’s 11th move, after which his game was strategically lost. Bronstein remarked, with some exaggeration, that every Russian schoolboy knows you must recapture with the pawn!’

C.H.O’D. Alexander annotated his loss on pages 30-31 of the January 1959 BCM, and below is a diagram of the position after 11 exf5, together with Alexander’s note on his reply, 11...Bxf5:

![]()

Alexander’s final words in this note are worth pondering:

‘As Bronstein said, “If White has played O-O, Black may just be able to afford BxP but if he has not it is fatal” – and every Russian schoolboy knows this!’

Were it not for what P.H. Clarke wrote in CHESS, we would automatically interpret the ‘schoolboy’ remark as Alexander’s own addition to the words of Bronstein which he had just quoted.

It is still unclear why the remark has been ascribed to Botvinnik. On page 113 of volume three of his trilogy Shakhmatnoe Tvorchestvo Botvinnika (Moscow, 1968) Botvinnik described 11...Bxf5 as ‘a typical strategic error in the King’s Indian Defence’ and stated that 11...gxf5 was forced, but made no reference to schoolboy knowledge:

(4891)

From Leonard Barden (London):

‘I was in Munich in 1958, and my memory is that Bronstein made the “schoolboy” remark. It is the type of phrase characteristic of Bronstein but not typical of Botvinnik. I can dimly recall Alexander retailing the criticism, with some zest.’

(4896)

Hans-Georg Kleinhenz (Munich, Germany) writes:

‘A predecessor of the famous “every schoolboy knows” quote can be found in the Carlsbad, 1907 tournament book (page 287), where Georg Marco comments on the opening moves of Leonhardt v Wolf:

“Die bisherigen Züge sind jedem A-B-C-Schützen [a pupil in the earliest class at school, who is learning the alphabet] aus dem kleinen Dufresne bekannt.”’

We note that the English-language edition of the tournament book (Yorklyn, 2007) has a curious mistranslation:

‘These moves have been known to every beginner since the days of the young Dufresne.’

The phrase ‘kleinen Dufresne’ (‘little Dufresne’) has nothing to do with Dufresne’s age (or size). Marco was stating that the opening moves of Leonhardt v Wolf were well-known owing to their inclusion in Dufresne’s ‘little’ introductory manual (Kleines Lehrbuch des Schachspiels).

(5367)

Sergei Prokofiev

The following article by Mikhail Botvinnik was published on pages 281-283 of S. Prokofiev Autobiography Articles Reminiscences (Moscow, 1959). It was dated 1954, the year after Prokofiev’s death.

‘My first introduction to Prokofiev and his music occurred at one of the musical appreciation lessons that were a regular part of the curriculum at school No. 157 in Leningrad which I attended in the early twenties. These lessons were essentially little chamber concerts with explanations by the music teacher. As a rule we were given classical music, but one day our teacher said that she was going to play something rather out of the ordinary.

She told us about a young composer named Sergei Prokofiev and his original style. “It is impossible to be indifferent to his music”, she told us. “Some people believe him to be exceptionally talented, others disapprove of him altogether. When I addressed a gathering of music teachers recently and announced that I was going to play the music of Prokofiev I was given an extremely chill reception. But when I had finished playing, the audience applauded wildly and I had to play an encore. I shall play the same piece to you now.”

If I am not mistaken the name of the piece was Despair. It made a deep impression on all of us. Unfortunately I have never heard it since; if I had I should recognize it at once.

I met Prokofiev in 1936 at the height of the Third International Chess Tournament in Moscow. He was a first-rate chessplayer himself and never missed a match. His position in the tournament was a delicate one and he maintained a strictly neutral attitude throughout, for while his sympathies were naturally with me as the young Soviet champion, he could not wish for the defeat of the ex-world champion Capablanca, who was a personal friend of his.

Several months later Capablanca and I shared first place at the tournament in Nottingham, England. When the tournament was over I received a telegram of congratulations from Sergei Sergeyevich. I was naturally very pleased and, without thinking, I showed the wire to Capablanca, who was with me at the time. At once I saw that I had made a mistake – from the expression on Capablanca’s face I realized he had not received a wire from Prokofiev. Two hours later Capablanca came to me beaming – he had received a telegram too. Of course, Sergei Sergeyevich had sent both wires at the same time, but evidently the Moscow telegraph office clerks had felt that the Soviet champion ought to get his message first.

Sergei Sergeyevich was passionately fond of chess. He took part in the chess activity of the Central Art Workers’ Club. Moscow chessplayers still remember his rather unique match with David Oistrakh – the winner was awarded the Art Workers’ Club prize and the loser had to give a concert for the club members.

I played chess with Prokofiev several times. He played a very vigorous, forthright game. His usual method was to launch an attack which he conducted cleverly and ingeniously. He obviously did not care for defence tactics. His illness did not lessen his interest in chess. In May 1949 the well-known chessplayer J.G. Rokhlin and I paid a visit to Prokofiev at his country place at Nikolina Gora. Sergei Sergeyevich was ill in bed and looked very poorly, but as soon as he saw Rokhlin he livened up. “Where is that volume of the 1894 Steinitz and Lasker chess match you promised me?”, he demanded. Poor Rokhlin, who had clearly forgotten all about it, was much embarrassed.

In the summer of 1951 Sergei Sergeyevich entered as one of the participants in a demonstration of simultaneous play I was to give at Nikolina Gora. His doctors, however, forbade it, but that did not prevent Prokofiev from following the games with his usual avid interest. I believe that was the last chess contest he ever attended.’

The photograph of Prokofiev at the start of the present item appeared in the same book. Botvinnik also related the 1936 and 1949 episodes on pages 55 and 126 of his autobiography Achieving the Aim (Oxford, 1981). See, furthermore, the references to Prokofiev in our feature article on him. Russian translation: Сергей Прокофьев и шахматы.

(4913)

Identifying everyone in this photograph is far from easy, and readers’ assistance will be appreciated.

(4919)

From Grzegorz Siwek (Warsaw):

‘Among the persons seated are, of course, Capablanca (second from the left) and Botvinnik (far right). Standing on the far right is Grigory Goldberg, who became Botvinnik’s second in his world championship matches in the 1950s. On his right is Jakov Rokhlin (Rochlin), and then comes Botvinnik’s wife Gayane and another chess writer, Samuil Weinstein (Vainstein).’

We now note that a second group photograph taken in the same room was published in the plates section of volume one of Botvinnik’s Best Games (Olomouc, 2000). Weinstein, Rokhlin, Capablanca, Botvinnik and Goldberg were identified in the caption, which also specified: ‘In the interval of ballet “Don-Kikhot”, Leningrad, 1933’. That cannot be correct since the Cuban’s first visit to the Soviet Union in the 1930s was not until 1935.

(6186)

A photograph of Jacob Bronowski opening the Hastings, 1961-62 event appeared on page 119 of the mid-January 1962 issue of CHESS:

The next page reported:

‘Dr Bronowski, opening the congress, disclosed that he had played chess all his life “with pleasure and passion” and considered himself fortunate to have lived through the most tremendous half century in the development of the game. It was just 50 years since the public had suddenly become excited about chess: it began with the great San Sebastián tournament of 1911, when Capablanca first sprung to fame.

At the age of 14 Dr Bronowski learned chess and was taken by his father to a simultaneous exhibition by the then boy prodigy Reshevsky. When he entered the room, he was taken for Reshevsky and got a round of undeserved applause. In 1945 he had played for the Civil Service against a scratch team and found himself faced by a young boy in knickerbockers who had signed his score-sheet “Jonathan Penrose”.’

(4965)

The remark quoted in C.N. 4970 (‘If this is Golombek’s English, we will eat our hat. It is more like the English of a well-educated foreigner.’) appeared on page 340 of CHESS, 15 July 1964 in a brief review of a book translated and edited by Golombek, Grandmaster of Chess The Early Games of Paul Keres (London, 1964).

We recall too Wolfgang Heidenfeld’s review of World Chess Championship 1957 by H. Golombek (London, 1957) on pages 60-61 of the March 1958 BCM. Whilst praising aspects of the book, Heidenfeld quoted a passage describing the start of the third match-game, where ...

‘... the author uses over 40 words to say exactly nothing. One is almost surprised that he does not record the fact that both players were breathing (you know, by inhaling air). Could any of the stuff he sees fit to describe be of the slightest interest to any chessplayer anywhere in the world?’

Heidenfeld stated that there was ‘far too much of this meaningless verbosity throughout the book’ and he also raised an analytical point that is worth noting. Having remarked that the analysis was sometimes ‘very good’, Heidenfeld added that the annotations were ‘quite often extremely superficial’. As an example he referred to page 104 (the 17th match-game):

White (Botvinnik) played 24 Rxc8+, and Golombek wrote:

‘In this phase of the game Botvinnik is scarcely recognizable. Now he meekly surrenders command of the QB-file without gaining the slightest compensation elsewhere. At least he should try for a K-side attack by 24 P-Kt4.’

Heidenfeld commented:

‘The annotator overlooks that the 24th move is virtually forced; that, in other words, Botvinnik is compelled to surrender the queen’s bishop’s file, meekly or otherwise, with or without compensation. For if he plays 24 P-Kt4 as recommended, there follows 24...RxR 25 QxR N-K5! – and with the queen deflected from Q3 and no piece able satisfactorily to protect the knight, White could hardly avoid 26 KtxKt PxKt 27 Kt-Q2 R-QB1 28 Q-Q1 B-Q6 29 B-B1 Q-Kt4, with a completely won position, which would not even offer White the chances he still obtained in the game.

It is absurd to imagine Golombek should not have seen this simple sequence of moves. Unfortunately, in this book, quite unlike his usual self, he seems to be too anxious to comment for the sake of commenting, which is precisely the attitude of mind that produces such superficialities.’

In a letter published on page 105 of the April 1958 BCM P.H. Clarke commented on the position after the 29th move in Heidenfeld’s line:

‘... unfortunately the South African master has not seen that after 29...Q-Kt4? ... White has a simple and obvious reply in 30 KtxP. Had he himself given the position more than a superficial study he might have noticed that 29...R-B7 (or even 29...Q-Q4) was the correct way to continue.’

On page 137 of the May 1958 BCM Heidenfeld acknowledged that he had been careless but stated that his error had not invalidated his criticism: ‘whether the line suggested ends in Q-Kt4? or R-B7! has no bearing on the fact that the original note in Golombek’s book – and unfortunately not this note alone – is carping and unnecessary criticism.’

We see that Smyslov’s own note to move 24 suggests that Rxc8+ was necessary and makes no mention of Golombek’s 24 g4:

‘White concedes the open file, since if 24 Bf1 there could have followed 24...Rxc1 25 Qxc1 Rc8.’

Source: page 296 of Smyslov’s Best Games Volume 1: 1935-1957 by V. Smyslov (Olomouc, 2003).

Vassily Smyslov

(4977)

See also our feature article Vassily Smyslov (1921-2010).

Harry Golombek’s Times column of 27 May 1978 (page 9) discussed Irving Chernev’s book The Golden Dozen (Oxford, 1976) concerning the 12 greatest players of all time. Noting that Morphy, Steinitz and Tarrasch were ‘strange omissions’, Golombek considered that the criteria should concern ‘not only prowess as a player but also what these great players have achieved and, most important, what contributions they have made to the knowledge and theory of chess’. Taking those factors into account, he offered as his top six, ‘in chronological order’, Morphy, Steinitz, Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine and Botvinnik, and observed:

‘Perhaps (and here it is necessary in the interests of brevity to overdo the comparatives and superlatives) one might say that Morphy was the greatest player of the game, Steinitz the greatest innovator, Lasker the greatest practical player, Capablanca the greatest natural genius, Alekhine the most perfect player and Botvinnik at his best (and this best lasted quite a time), the most magnificent player the world has yet seen.’

Rather oddly, Golombek then added:

‘Nor am I by any means convinced that this is really and absolutely the top six. There are a dozen more, any one of whom could be among the leading six: Anderssen, Chigorin, Tarrasch, Rubinstein, Keres, Smyslov, Bronstein, Boleslavsky, Tal, Spassky, Fischer and Karpov.’

The idea of Boleslavsky being among the half-dozen greatest players of all time is certainly challenging.

M. Botvinnik and H. Golombek, Alekhine Memorial, Moscow, 1956

(5215)

See also Harry Golombek 1911-95.

Jon Crumiller (Princeton, NJ, USA) recalls a passage on page 205 of The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal by M. Tal (New York, 1976). It comes from Tal’s note to his 28th move (...Bf4) against Botvinnik in game six of their 1960 world championship match:

‘Unfortunately Black missed a possibility to end the game quickly and beautifully by 28...RxN! 29 R(3)xR R-Q8 30 R-B4 B-N7. Of course there were more than chess reasons for this: the noise in the auditorium had prompted the referees of the match to carry out their threat and move the game to a closed room. This of course turned to be an extremely severe warning to the spectators and in the following games there was no need to take such measures, but one does not feel very pleasant when, with an hour remaining on the clock, one is politely asked to move into the wings in the very heat of battle ... in any case, I am not used to playing in “nomadic” conditions.’

(5123)

Page 14 of Chess World, 1 January 1947 quoted from an article by Botvinnik in Ogonyok which was subsequently published in Albrecht Buschke’s periodical Chess News from Russia. An extract is given below:

‘During the Nottingham tournament of 1936 I happened to watch a curious scene. Bogoljubow was sitting deeply bent over the board, and was thinking tensely. Alekhine was briskly wandering around the table, fixedly looking at his opponent. Willy-nilly, I became interested, drew near to the table and saw the position after Alekhine had made his 35th move P-N5 [g5].

What can Black do? He has an extra pawn, but the situation is tense and the material superiority does not tell. White threatens 36 PxP, after which his bishop would be very strong.

Bogoljubow played 35...PxP. He had not taken the pawn off the board when Alekhine hurriedly approached and, without sitting down, played 36 P-B5!!, noisily banging down the piece. This sacrifice was so unexpected that Bogoljubow literally jumped out of his chair, in spite of his solid constitution. Evidently he had figured only on 36 PxPch K-N1; and in view of the threat, ...P-K4, Black’s situation would be quite secure.’

Alekhine’s annotations to the game can be found in the Nottingham, 1936 tournament book and in his second volume of Best Games.

(5348)

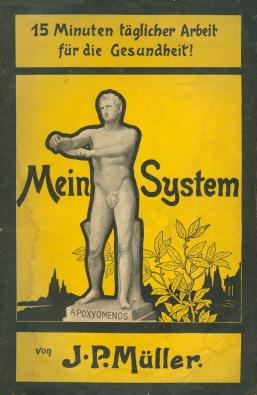

Tim Bogan (Chicago, IL, USA) quotes from page 5 of Achieving the Aim by Mikhail Botvinnik (Oxford, 1981):

‘I was a round-shouldered lad with a flat chest and didn’t go in for sport. Mother introduced me to a tall well-built young lady, probably one of her patients (Mother was a dentist). As a present I was given a book by Muller which was well known in those days. I tried to live according to Muller, and quite liked it. For the half-century or so since then I have done morning exercises. The weak lad straightened up and, as they say nowadays, noticeably “filled out”.’

Front cover of the first German edition of J.P. Müller’s book

(5581)

For more on the Müller book, see Nimzowitsch’s My System.

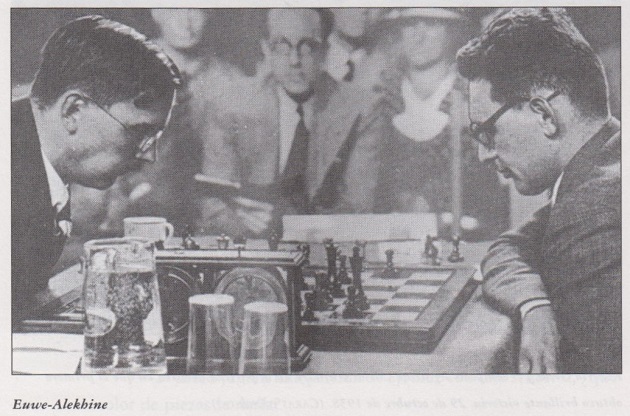

Max Euwe and Mikhail Botvinnik in a photograph published opposite page 161 of Euwe’s book Wereld-Kampioenschap Schaken 1948 (Lochem, 1948)

(5613)

See also Max

Euwe (1901-81).

Alan O’Brien (Mitcham, England) notes that on page 2 of Anatoly Karpov His road to the World Championship by M. Botvinnik (Oxford, 1978) a mate in one was missed in the notes to the first match game between Polugayevsky and Karpov, Moscow, 1974:

Position after 22 Kh1 (analysis by Botvinnik)

Rather than 22...Ng3+ Black has 22...Qg1 mate. We see that the error was already on page 17 of the Russian edition, Tri Matcha Anatolia Karpova (Moscow, 1975).

(5669)

C.N. 5884 quoted a remark from page 50 of Better Chess by William Hartston (London, 2003): ‘Think strategies when it’s your opponent’s turn to move; sort out the tactics while your own clock is running.’

Paul Dorion (Montreal, Canada) notes a passage on page 139 of Think Like a Grandmaster by Alexander Kotov (London, 1971):

‘When later I was busy writing this book I approached Botvinnik and asked him to tell me what he did when his opponent was thinking. The former world title-holder replied in much the following terms: Basically I do divide my thinking into two parts. When my opponent’s clock is going I discuss general considerations in an internal dialogue with myself. When my own clock is going I analyse concrete variations.’

(5889)

Elmer Sangalang (Manila, the Philippines) writes:

‘In a simultaneous exhibition in 1947 the ten-year-old Boris Spassky won against the future world champion Mikhail Botvinnik. Is the game-score extant? In 1990 Spassky wrote to me that he did not have it.’

For a photograph of the occasion, see the front cover of the 7/1988 New in Chess.

(5932)

From our feature article on Boris Spassky:

An interview of fine quality appeared in ‘Portrait of a World Champion’ by Leonard Barden on pages 7-13 of the January 1970 issue of Chess Life & Review. Much of the interview (conducted in 1966) is quotable, but here we focus on some of Spassky’s comments on other masters:

‘Botvinnik told me that he disagreed with people who like to compare Petrosian with Capablanca. Capablanca, says Botvinnik, was a genius who could always find a new plan in a position. Petrosian doesn’t do that; he begins to maneuver, and this is a great difference, because a chessmaster of the highest class must always be able to find fresh ideas. I feel myself that Botvinnik’s comment is only part of the truth; Petrosian is better than he says. Tal told me that Petrosian is a very careful player; not passive, but a little bit cowardly. He’s a very practical man; a real Armenian. Capablanca was quite the opposite; he was an optimist, and he played very simple and pure chess.’

‘In our time, only when Mikhail Tal appeared did chessplayers see that there could be a different style. Tal has had a great influence on our chess; he stands out in the same way as the old champions. Probably there have been two pure geniuses in chess; Morphy and Capablanca. Tal is also a genius as a tactician, but because he makes a lot of unsound sacrifices this is not pure genius; Morphy and Capablanca hardly ever made tactical mistakes. Perhaps Rubinstein was also a genius of positional chess, and his playing style was also very pure; but he was a bad tactician.’

‘... I believe that the real grandmaster of the super class has to follow the logical course from the beginning to the end of a game. It is necessary to work out all the right tactical decisions which justify your ideas. Sometimes I am too lazy to do this properly, and that is a very, very bad attitude for a grandmaster. I do not believe that Capablanca, Alekhine or Lasker had this particular problem.’

From Chess and Computers:

An interview with Botvinnik on computers in Soviet Weekly was reproduced on pages 194-195 of CHESS, 25 February 1961.

A cautious reply from Botvinnik to an interview quoted on page 120 of CHESS, January 1962:

‘In how many years do you think chess by electronic computers will become a serious factor in the game?’

‘I believe the time when an electronic machine will begin to play chess is not far off.’

Page 8 of CHESS, October 1968 included the following remark by Botvinnik when addressing 400 people in Vladimir in late July:

‘I forecast an unprecedented period of popularity for the game. When an electronic machine has started playing chess and played it successfully this will be such a momentous event that every schoolboy will want to know about it. In world history, it will perhaps fall not far short in importance of the discovery of fire.The young will have to study not only computer technique and programming but also chess itself. And then when a hundred times more young people study chess, when many of them devote their lives to it, then we shall have a real chance of getting a new generation of Tals and Spasskys.’

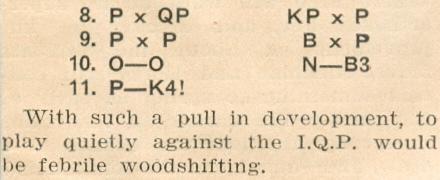

‘The isolated queen’s pawn is an important learning element in chess strategy. The late Bob Wade first coined the term IQP in his 1963 book on the World Championship match between Botvinnik and Petrosian.’

Source: Raymond Keene, in his chess column in The Times,

11 April 2009, page 95.

With Google Books it takes about ten seconds to find earlier occurrences of ‘IQP’, one instance being in The Return of Alekhine by C.J.S. Purdy (Sydney, 1938). We add that the text in question, concerning the 19th match-game between Euwe and Alekhine, had already appeared on page 349 of Purdy’s Australasian Chess Review, 20 December 1937:

For our part, we would never claim that even Purdy ‘first coined the term IQP’ (or that it was only in 1937 that he first used it).

(6074)

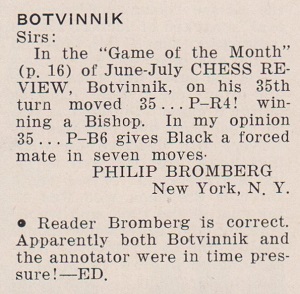

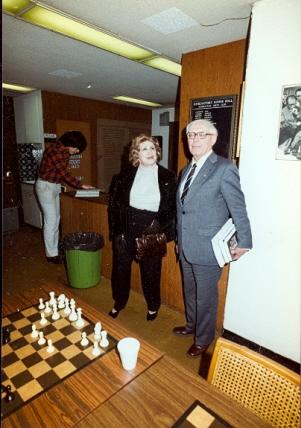

Two contributions from readers which originally appeared in 1983 (C.N.s 526 and 560) are reproduced below:

John C. Rather (Kensington, MD, USA) writes:

‘Consider Botvinnik’s indifferent performance as a match player. Despite his long, albeit intermittent, tenure as world champion, he never won a match when defending his title and his overall record of +2 –3 =2 in matches and +36 –39 =82 in points is not impressive.

If one believed in the conspiratorial theory of chess history, the drawn matches with Bronstein and Smyslov and what seemed like the Alphonse-and-Gastoning that followed might be thought to be part of a plot to aggrandize Soviet chess. However, a closer look at Botvinnik’s cumulative performance in the seven matches suggests a more plausible explanation. In games 1-8 he scored +16 –13 =27; in games 8-16 the tally was +15 –11 =30; but after game 16 he could do no better than +5 –15 =25. Surely this raises a question about his physical and/or psychological stamina.

He did come from behind in his 1933 match with Flohr (+2 –2 =8 ), but the closing collapse occurred against Levenfish in 1937 when he scored only +1 –3 at the end, to allow the +5 –5 =3 result. The date of the latter match indicates that his problems in the championship matches may not be attributed to his age alone.’

From William Hartston (Cambridge, England):

‘I had a conversation with Spassky last year which I think throws some light on C.N. 526 (Botvinnik’s match record). I had always supposed that Botvinnik took his first matches rather lightly, in the knowledge that he had the right to a return match if he lost. Spassky’s explanation was more convincing, bearing in mind what we know about Botvinnik’s meticulous approach. He claimed that Botvinnik had already started his preparations for the return match while the first match was in progress. Indeed, one might even accuse him of using the first match as part of those preparations. The exhausting process of winning through the qualifying tournaments, then beating Botvinnik left Smyslov and Tal too exhausted to put up a fight in the “serious” match which followed. With that gloss on chess history, we should perhaps be less impressed with the achievements of Bronstein and Smyslov in 1951 and 1954 in “only” drawing with a man who was just sizing them up for the big fight. Spassky said that he once told Botvinnik of his conclusions; the old man just glared at him and said, “You are very clever”.’

Frontispiece of Botwinnik lehrt Schach by Hans Müller (Berlin-Frohnau, 1967)

(7137)

Rick Massimo (Providence, RI, USA) points out a remark by Igor Botvinnik about his uncle on page 9 of Botvinnik-Petrosian The 1963 World Chess Championship Match (Alkmaar, 2010):

‘I had the impression that he did not like to be reminded of this match loss, and it was a subject we hardly ever spoke about. However, when he occasionally talked about the pre-match negotiations, and the story of Petrosian’s sealed move in Game 5, he did say that his nerves had been “preyed upon”.’

Finding no information elsewhere in the book regarding an incident in the fifth game, Mr Massimo asks what happened.

Botvinnik gave the following account on pages 171-172 of Achieving the Aim (Oxford, 1981):

‘I played the match not too well. A definite effect on my state of mind was produced by an incident in the fifth game. At the start of the adjourned session (the game was adjourned in a winning position for Petrosian) the judge Golombek (England) opened the envelope and, after looking at Petrosian’s score sheet, made a losing [sic] for Petrosian. The latter protested energetically; then Golombek shrugged his shoulders and made the move which my opponent insisted on.

After my loss in this game I approached Golombek for an explanation (according to the rules if the judge is doubtful about which move has been made, i.e. if there is an inaccuracy in the writing, then a loss is awarded). Golombek replied that the move was indeed not clear, but he was not in agreement with such an interpretation of the rules. I was infuriated. This legal point had been decided when I was still a young man. I approached Ståhlberg – he supported the position of his colleague.

Then I demanded a photocopy of the score sheet. This was provided a week later. All week I was nervous and managed to lose yet another game. However, the unpleasantness lay in the fact that although Petrosian had written the move down inaccurately there could be no doubt about deciding what move had been sealed, and Petrosian had complete justification for his protest at the adjournment.

I felt bitter at my old friends, the match judges. I just couldn’t understand why they had created such a groundless conflict.’

Golombek covered the match for the BCM, with much detail on matters large and small, but we see no reference to this adjournment incident. Petrosian’s sealed move was 41 Kf7. Is it known whether his score-sheet for the game has survived?

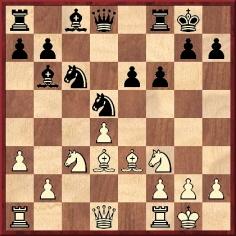

(7141)

White to move (adjournment position)

Peter Wood (Hastings, England) cites the note to 41 Kf7 on page 147 of Tigran Petrosian His Life and Games by Vik L. Vasiliev (London, 1974):

‘Undoubtedly the strongest, which unexpectedly called forth a protest from the opponent. Here Botvinnik turned to the match arbiter and claimed that White had sealed the impossible move 41 K-B8?? (into check!).

One of Petrosian’s “small weaknesses” is that he has a habit of writing the number 7 with a round tail ... in a word, the mediation of the judge was called for, and after the truth of the matter was established, play continued. The nervous strain of a hard match sometimes produces the most unexpected conflicts!’

(7146)

See also our feature article on Tigran Petrosian.

Mikhail Botvinnik

Writers on Mikhail Botvinnik tend to pass over a significant article which he contributed to International Championship Chess by B. Kažić (London, 1974). Published on pages 244-250, it is entitled ‘Botvinnik on his Meetings with World Champions’ and discusses Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine and Euwe. An observation from page 248:

‘Alekhine’s was a complex character. As soon as he felt any signs of hostility, he would shoot out his quills like a porcupine. When people were kind he felt bound to behave in the same way.’

We should like to know whether Botvinnik’s original text is available, since the English version is sometimes defective. For example, page 247 has the following regarding AVRO, 1938:

‘The tournament marked the greatest in Capablanca’s entire career.’

A word such as ‘failure’ or ‘disappointment’ seems to be missing after ‘greatest’.

There is an interesting passage on pages 246-247, concerning the period after Hastings, 1934-35:

‘At the invitation of S.O. Weinstein, Capablanca came to the Soviet Embassy in London and immediately agreed to play in Moscow. It was a while before Capablanca actually came. Weinstein inconsiderately asked him about a possible match with Alekhine and suddenly the Cuban changed colour! He glared and could not calm down for a long time. Capablanca and Alekhine remained enemies for the rest of their lives.

Capa was phenomenal at calculating positions, but he was also a shrewd tactician. At the tournament in Moscow I played Black and skilfully brought the game to even play, when, unexpectedly, Capablanca in the end “overlooked” a man!? But – no! White had, in fact, been preparing a quiet move and a variation in which he actually took the pawn. All of this was artfully concealed.’

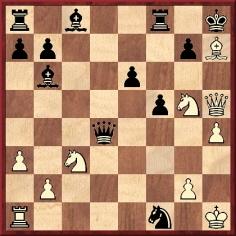

The description appears to concern the play in connection with Capablanca’s move 19 Rxa7 against Botvinnik in the Moscow, 1935 tournament, with the curious variation featuring 22 Kf1. Below is the relevant part of the tournament book (page 135), with notes by Ilya Rabinovich:

See too pages 92-93 of the English edition of the tournament book (Yorklyn, 1998). Botvinnik’s own notes appeared in the first volume of his Best Games series; for instance, on pages 181-183 of the English edition (Olomouc, 2000).

Three photographs taken during the game come to mind. The first was published opposite page 216 of Homenaje a José Raúl Capablanca (Havana, 1943) and opposite page 16 of Botwinnik lehrt Schach by H. Müller (Berlin-Frohnau, 1967):

Next, there is a shot included in the plate section of Botvinnik’s autobiography K Dostizheniyu Tseli (Moscow, 1978):

A third photograph may be viewed on-line at the RIA Novosti website.

Botvinnik’s autobiography (page 51) mentioned the game, stating that he arrived ten minutes late because he had forgotten his glasses. That passage is on page 42 of the English translation, Achieving the Aim (Oxford, 1981).

(7263)

Karel Mokrý (Prostějov, Czech Republic) informs us that he investigated this Moscow, 1935 photograph in the 1980s and drew up the key given below:

Mr Mokrý also mentions an article which he has written on the two variations of the Russian-language tournament book and the subsequent removal of Krylenko’s name and contribution. See under ‘Moscow 1935’ in the ‘Collector’s Corner’ of our correspondent’s webpage.

(7286)

From Photographs of Capablanca, a feature article which appealed for better copies of a number of images in Soviet publications:

Source: Moscow tournament bulletin, 64, 13 June 1936 and 64, 16 June 1936, page 1

In C.N. 7301 Philippe Pierlot (Le Perchay, France) provided a good-quality copy (source not yet identified):

Michael Clapham shares three photographs from his collection. Information on the reverse side suggests that they were taken during the Groningen, 1946 tournament.

(7323)

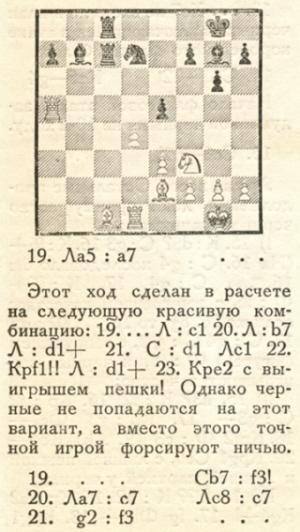

Knud Lysdal (Grindsted, Denmark) notes that the dancer is Botvinnik’s wife, Gayane. We reproduced the photograph in C.N. 7292 from opposite page 32 of Botwinnik lehrt Schach by H. Müller (Berlin-Frohnau, 1967). The one below is from opposite page 96 of Twelfth Chess Tournament of Nations by S. Flohr (Moscow, 1957):

(7311)

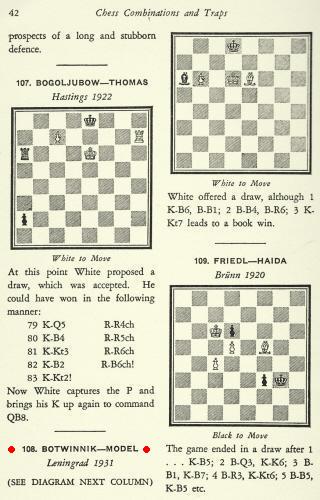

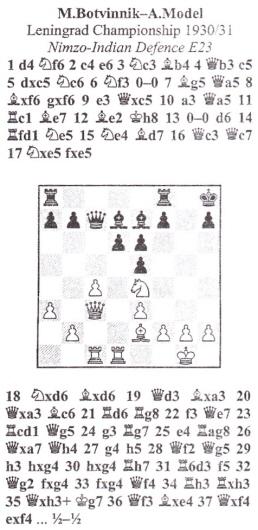

Below is page 42 of a book edited by Reinfeld, Chess Combinations and Traps by V. Ssosin (New York, 1936):

What more is known about the Botvinnik v Model position? We wonder whether it arose later in the game which was given in part on page 217 of Botvinnik’s Complete Games (1924-1941) and Selected Writings (Part I) (Olomouc, 2010):

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Qb3 c5 5 dxc5 Nc6 6 Nf3 O-O 7 Bg5 Qa5 8 Bxf6 gxf6 9 e3 Qxc5 10 a3 Qa5 11 Rc1 Be7 12 Be2 Kh8 13 O-O d6 14 Rfd1 Ne5 15 Ne4 Bd7 16 Qc3 Qc7 17 Nxe5 fxe5 18 Nxd6 Bxd6 19 Qd3 Bxa3 20 Qxa3 Bc6 21 Rd6 Rg8 22 f3 Qe7 23 Rcd1 Qg5 24 g3 Rg7 25 e4 Rag8 26 Qxa7 Qh4 27 g4 h5 28 Qf2 Qg5 29 h3 hxg4 30 hxg4 Rh7 31 R6d3 f5 32 Qg2 fxg4 33 fxg4 Qf4 34 Rh3 Rxh3 35 Qxh3+ Kg7 36 Qf3 Bxe4 37 Qxf4 exf4, and the game was subsequently drawn.

(7548)

Page 89 of the September-October 1943 American Chess Bulletin had an interview with Botvinnik published in ‘a recent issue of the “Information Bulletin” of the USSR Embassy at Washington’. The future world champion’s remarks included the following:

‘The War has caused many losses among Soviet chessplayers. The talented young masters Sergei Belavenets, Joseph Rudakovsky and Lev Kaiyev have perished in battle for their country. Mark Stolberg, 18-year-old [sic] Rostov master, is missing in action. A German bomb killed Alexander Ilyin-Zhenevsky, one of the old Russian masters, who at a tournament in Moscow in 1935 [sic – 1925] won a sensational game from Capablanca, then world champion. I was personally indebted to Ilyin-Zhenevsky for organizing my match with Grossmeister Salo Flohr in 1933. Ilyin-Zhenevsky was at that time working in the Soviet diplomatic mission in Prague. Also among the missing are the masters Ilya Rabinovich, participant in many international chess tournaments, and Nikolai Ryumin, whose name swept the entire chess world in 1935 when he won a victory over Capablanca in the first round of the Second Moscow International Tournament.

Other gifted players are taking the places of those who have gone. In the city championship tournament in Tashkent, 16-year-old Mark Makov [sic – Taimanov] shared the first and second prizes with Grossmeister Salo Flohr, who has become a Soviet citizen and is now residing in Tbilisi, capital of Georgia. Considerable improvement is noticeable in the playing of Vasili Smyslov and Isaac Bogoslavsky [sic – Boleslavsky].’

Regarding Rudakovsky, Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia states that he died in 1947, in Chernovtsy.

(7680)

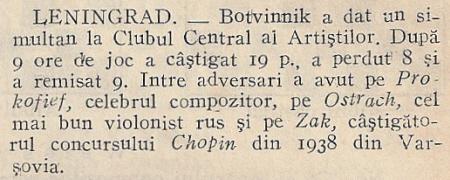

Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) draws attention to a news item on page 164 of the Revista Română de Şah, 24 August 1939:

It states that Botvinnik gave a simultaneous exhibition at the Central Artists’ Club in Leningrad, scoring, after nine hours’ play, +19 –8 =9, and that his opponents included Prokofiev, Oistrakh and Zak.

Our correspondent writes:

‘What is known about the chess interest of Yakov Zak (1913-76), the winner of the 1937 Warsaw Chopin Competition? (The date 1938 in the Romanian magazine is incorrect.) He was one of the great names in Soviet piano performing and teaching and was famous for his performances of Prokofiev’s music.

Regarding the photograph in your feature article Sergei Prokofiev and Chess, the girl watching Oistrakh and Prokofiev, Elizaveta (Liza) Gilels, was the sister of the pianist Emil Gilels, the wife of the violinist Leonid Kogan, and the mother of the violinist and conductor Pavel Kogan. She herself was an accomplished violinist.’

(7726)

In C.N. 1243 (see page 161 of Chess Explorations) W.D. Rubinstein drew attention to a booklet published in Madras in the mid-1980s, Karpov’s Best Games by V. Ravi Kumar (or Ravikumar). From the author’s introduction, entitled ‘Karpov “The Man Machine”’, a few sentences (to use that noun loosely) were quoted:

‘He was awarded the Chess Oscar for his outstanding achievements in Chess. A honour which he won many times in succession Karpov is a Solid Positional Master but if the situation warrants he can glar himself to a tactical Genious. In the chapters that follows of his selected Games from 1980 to 1984 are annotated with my own notes for your entertainment.’

Also regarding the introduction, it remains to be discovered on what grounds the author attributed this remark to Botvinnik:

‘Anatoly Karpov is unquestionably the strongest chess player of the century.’

(7790)

Below is an article by G.H. Diggle from page 69 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984). It was originally published in the June 1981 Newsflash.

‘The nine world championship matches (Russians only) which spanned the ’50s and ’60s did not greatly excite the outside world, which accepted Soviet Chess as unapproachable in stature by the rest of mankind, and regarded all Russian grandmasters as “Dinosaurs” with unpronounceable names. Moreover, as international rivalry and politics were “out”, the Press had nothing to report but chess, which was, of course, fatal. Worse still, the combatants were good friends and good sportsmen, and so of “unfortunate incidents” and “embarrassing moments” there was complete dearth in the land. It is true that, for the first time in chess history, the matches were great public spectacles in themselves, staged in magnificent concert halls with the contestants spotlighted on platforms before audiences running into thousands. But some press reports at the time were so “overwhelming” that they ended up as masterpieces of anti-climax – the Badmaster misquotes from his “Munchausen” memory: “Hours before play commenced, the great opera hall was filled with great-grandmasters, grandmasters and international masters; outside in the snow, hundreds of masters and candidate masters, unable to obtain admission, listened to a running commentary broadcast by Grandmaster Ponderovsky. After ten moves a draw was agreed upon. ‘A true grandmaster epic’, as Ponderovsky sardonically remarked.”

But any person so unreasonable as to prefer fact to fantasy should refer to the BCM for 1954, 1957 and 1958, where full accounts of the three great Botvinnik-Smyslov matches are given by “H.G.”, who acted as judge throughout all three. Botvinnik then aged 42 (Smyslov was ten years younger) just retained his title in the first match, a magnificent struggle full of collapses and comebacks ending 12 games all, lost it in the second (9½-12½) and regained it in the third (12½-10½). The fighting quality of both masters can be gauged from the fact that of the whole aggregate of 69 games, only four “grandmaster draws” can be traced, and three of these were at the end of the second match, when Botvinnik clearly had no chance of catching up. The audience (apart from the “grandmaster element”) are described by H.G. as “keener and more knowledgeable than spectators in other countries” and varied from “much beribboned soldiers of high military rank” to the “average artisan”. They were an impartial crowd, though in the 14th game of the third match, when Botvinnik by winning after 68 moves established a 9-5 lead and almost ensured regaining the title, the crowd invaded the playing arena in their delight that “the old man had done it again”. Yet in the very next game Botvinnik, with a winning ending, completely forgot the clock and (for the only time in his whole career) lost on time-limit, thereby (as it turned out) postponing his final victory for another fortnight.

No fewer than 13 of the games lasted exactly 41 moves, owing mainly to resignations without resuming play, after the opening of sealed envelopes the “shrewd contents” of which doubtless resembled those which “stole the colour from Bassanio’s cheek”.’

(8091)

Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA) asks whether Hans Ree was right to state on page 128 of the 7/2013 New in Chess:

‘Botvinnik has said that a world championship match, with everything that it involves, would take one year off one’s life.’

The best supporting quote that we can offer is a paragraph by Harry Golombek about the 1963 Botvinnik v Petrosian match, on page 115 of Chess Life, May 1963:

‘Both contestants have shown, on and off, undoubted signs of strain and both have given utterance to their thoughts on the matter. Botvinnik has said that each world championship match has cost him a year of his life. He may have meant by this that the necessary preparation for such a match took a year, but it is still more likely that he meant the anguish and the pain caused by the whole contest shortened his life expectation by one year.’

(8397)

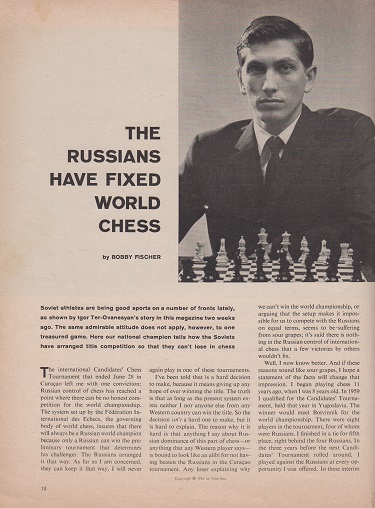

We offer a miscellany of observations by Mikhail Botvinnik published in English-language chess magazines. First, some excerpts from an interview in the Latvian magazine Šahs as presented by Eliot Hearst on page 135 of the June 1962 Chess Life:

‘This defense limits the possibilities of White. When the defenses P-K4, P-K3 or P-QB4 are employed, White has a much bigger choice of variations than in the case of the Caro-Kann Defense, where Black usually has a very solid position. As a result, in match-play the Caro-Kann is a very efficient weapon, since, in a match, one plays as White to win the game, whereas, as Black, one tries to merely obtain a satisfactory defense. And if, in the last Tal match, White got a slight advantage against this defense, the reason was not because of the opening itself, but because of errors committed later in the game.’

‘It is said that if one is beaten by someone, it is necessary to criticize the opponent; and if one beats someone, it is necessary to praise him. I think it is better to always be consistent ...