Edward Winter

From page 5 of the New York Times, 28 March 1889:

‘Many of the spectators and the managers were disappointed in Mason. He was pitted against D.G. Baird, but when he came into the hall he was laboring under excitement, and it was said that he had been imprudent enough to visit a barroom with some friends. Nevertheless he insisted on playing, but after making eight moves he had to retire, giving up his game to his opponent.’

Page 293 of the New York, 1889 tournament book published the game-score:

David Graham Baird – James Mason

New York, 27 March 1889

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 exd5 exd5 4 Nf3 Bf5 5 Bd3 Bxd3 6 Qxd3 Nf6 7 O-O Bd6 8 Re1+ and ‘Game lost by forfeit’.

On page 237 of the August 1890 International Chess Magazine Steinitz described how in the New York tournament Mason ‘forfeited a game “by time” on the eighth move, and on several occasions, to speak in plain language, simply created disgraceful drunken disturbances’.

A further remark by Steinitz:

‘… Mr Mason when he descends from the heights of his obfuscated philosophy into the sober region of fact, has, so to speak, “no leg to stand upon”, which, of course, does not matter much to Mr Mason, who is notoriously rather unfamiliar with that sensation, outside of chess controversy.’

Source: International Chess Magazine, July 1885, page 208.

On page 138 of the May 1890 issue of his periodical Steinitz wrote: ‘Of course, Mr Mason’s manifesto must be taken cum grano whiskey.’ In the September 1885 number (page 265) a tournament reporter recorded being asked by a friend, ‘How is it that Mason has such a good chance of winning the first prize at Hamburg?’ The answer, with a reference to the tournament tail-ender, was, ‘Because he’s keeping Bier a long way off.’

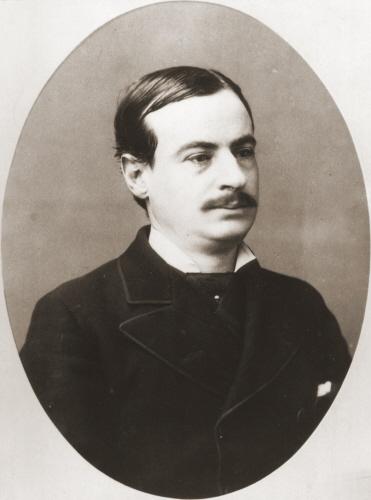

James Mason

These matters were originally discussed by us in Kingpin, and on page 15 of issue 10 we turned to J.H. Blackburne and, in particular, Stephen Fry’s comment on the well-known anecdote about a simultaneous exhibition at which a glass of whisky en prise was supposedly taken en passant: ‘What I like about that story is that it is so completely unfunny.’ Asking whether such an incident had occurred, we mentioned a letter to us from Bent Larsen (Buenos Aires) reporting that at Teesside in 1972 he had met an eye-witness to the episode (alleged to have occurred in Manchester).

Joseph Henry Blackburne was certainly fond of a sip, even though page 401 of the October 1924 BCM recorded his remark ‘my favourite beverage is castor oil’. Page 494 of the June 1899 American Chess Magazine quoted from the New Orleans Times-Democrat an interview which Blackburne had given to the Licensing World, an anti-temperance journal:

‘I find that whiskey is a most useful stimulus to mental activity, especially when one is engaged in a stiff and prolonged struggle. All chess masters indulge moderately in wines or spirits. Speaking for myself, alcohol clears my brain, and I always take a glass or two when playing.’

The Times-Democrat commented: ‘Mr Blackburne, with great frankness, proceeded to dilate further upon the joys of the bowl and the misery of its deprivation.’

Concerning the dark side to Blackburne’s drinking, see the statements about him made by Steinitz, as related in Chess with Violence.

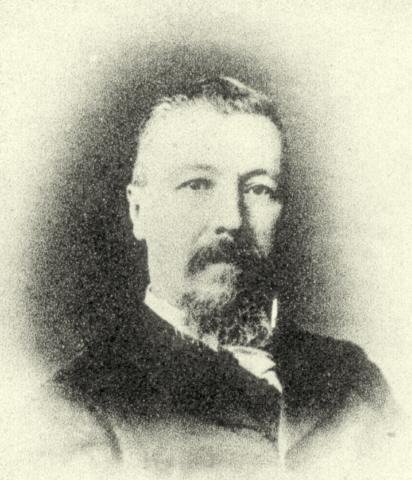

Joseph Henry Blackburne

A number of webpages and other outlets specializing in (i.e. making do with) unattested ‘chess quotes’ loosely attribute to Blackburne the remark ‘chess is a kind of mental alcohol’. The observation is to be found in an interview with Blackburne which originally appeared in the Daily Chronicle and was reproduced on pages 87-88 of the 1 May 1895 issue of the Chess Player’s Chronicle. C.N. 5940 gave the full item.

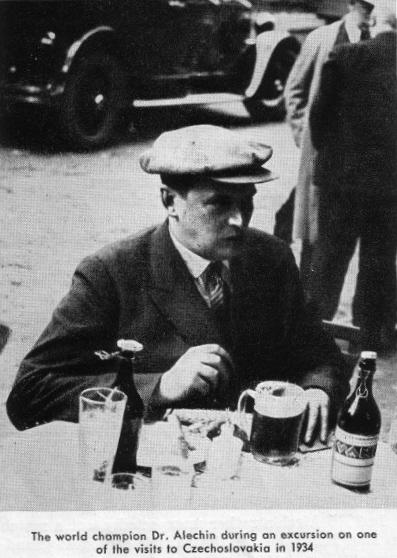

In C.N. 5524 Pierre Bourget (Quebec, Canada) offered this photograph, from page 6 of issue one of FIDE Revue, 1956:

Alexander Alekhine’s heavy drinking is not in doubt, and Pablo Morán’s monograph on him has a chapter entitled ‘Exhibitions Under the Influence’. There are, though, inferior writers (which is certainly not a description of Morán) who enjoy pouncing on and blowing up any great master’s adversities. See, for instance, the examples quoted at the start of our article The Games of Alekhine. A person [Raymond Keene] who writes that a champion played a world title match ‘more or less in a perpetual stupor’ is capable of writing any old thing about anyone.

In the interests of maintaining a sense of proportion, C.N. 3005 quoted pages 410-413 of the August 1978 Chess Life & Review, where Max Euwe was interviewed by Pal Benko. The exchange concerns the 1935 world championship match:

‘Benko: I have heard many rumors that Alekhine was drinking heavily during the match and was behaving strangely sometimes. Can you comment?

Euwe: I don’t think he was drinking more then than he usually did. Of course he could drink as much as he wanted: at his hotel it was all free. The owner of the Carlton Hotel, where he stayed, was a member of the Euwe Committee, but it was a natural courtesy to the illustrious guest that he should not be asked to pay for his drinks. I think it helps to drink a little, but not in the long run. I regretted not having drunk at all during the second match with Alekhine. Actually, Alekhine’s walk was not steady because he did not see well but did not like to wear glasses. So many people thought he was drunk because of the way he walked.’

The above article originally appeared at ChessBase.com.

The conclusion of our 1997 article in Kingpin (see also pages 238-239 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

The following game was published by the Cincinnati Commercial in 1881 but was not included in P. Anderson Graham’s monograph on Blackburne. Black’s name is appropriate to our theme.

Joseph Henry Blackburne (simultaneous) – Brewer

London, 1881

King’s Gambit Accepted1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Bg7 6 d4 Nf6 7 Nxf7 Kxf7 8 Bxf4 d5 9 Nc3 Nxe4 10 Nxe4 10 Nxe4 Re8 11 Be5 dxe4 12 Bc4+ Be6 13 O-O+ Kg8

14 Qxg4 Qd7 15 Bxe6+ Rxe6 16 Bxg7 Rg6 17 Rf8+ Kxg7 18 Qxd7+ Nxd7 19 Rxa8 Resigns.

With regard to Morphy’s origins, C.N. 3015 asked what was known about the connection between Morphy, Murphy and beer. It was recalled that H.R. Sadeghi (Lausanne, Switzerland) had sent us a beer-mat which bore a coat-of-arms identical to that of Morphy’s family (an item that we first published in Kingpin in 1995):

The black and white illustration comes from page 2 of the 1926 booklet Life of Paul Morphy in the Vieux Carré of New-Orleans and Abroad by Regina Morphy-Voitier, where the coat-of-arms was described as follows:

‘Morphy, alias Murphy. Quarterly argent and gules; four lions rampant interchanged, over all on a Fesse Sable three garbs or, Crest; a lion rampant holding a garb. (No Motto.)’

(3516)

Niall Woodger (Sandweiler, Luxembourg) writes:

‘Murphy and Morphy are derivations of the same name, both being Gaelic in origin, derived from “Murchadh”, meaning “sea warrior”. The Murphy brewery website states:

“The Murphy name is in fact the most popular name in Ireland and the Murphy family ... started the brewery back in 1856 as a noble family of the Cork region.”

The Brewery’s founder was James J. Murphy. An excellent website shows the Morphy coat-of-arms to be the same as the one you have displayed. There are six separate Murphy coats-of-arms given, of which four are almost identical to the Morphy one. Thus the Morphy and Murphy family histories are shown to be inextricably linked.’

(5068)

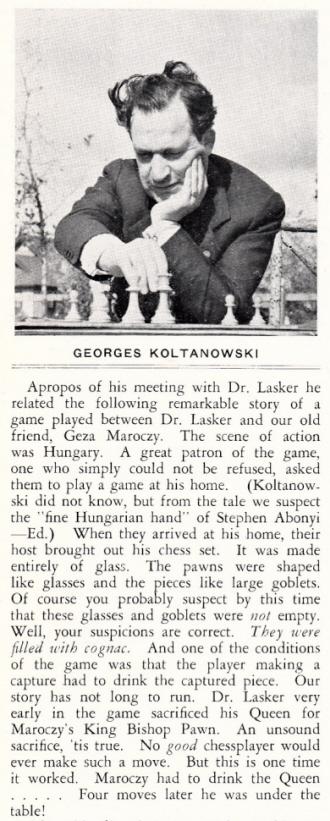

In an article on page 195 of the September 1971 Chess Digest Magazine William Winter was given the Koltanowski treatment:

‘Winter was a heavy drinker and one of the best chess stories I know is the one of the committee that was formed in 1927 just before the International tournament was to take place in London. They raised one hundred pounds (about 350 dollars then) to support William Winter, so that he could win the event with great ease. In the first round William Winter came into the playing hall, breathing harshly and he beat the great Richard Reti. The next day, Winter weaved into the playing room, sat down at his board and beat the perplexed Aron Nimzowitch. The third day Winter staggered to his seat and beat my co-patriot, Edgar[d] Colle. It looked like it was going to be a big triumph for British Chess. But the expectations were short-lived. Winter had spent all the raised funds on booze in the first three days, and the so-called Winter Committee couldn’t raise another penny from its supporters. The first prize was only one hundred pounds! William Winter arrived sober for each round after the third and lost every game.’

Let us, firstly, compare the above with the complete record of the tournament given in M.A. Lachaga’s comprehensive book on the event, published in 1968. William Winter’s round-by-round performance was as follows:

1: lost to Fairhurst

2: beat Buerger

3: beat Thomas

4: drew with Marshall

5: lost to Bogoljubow

6: drew with Yates

7: lost to Tartakower

8: beat Nimzowitsch

9: drew with Colle

10: lost to Réti

11: beat Vidmar.

This placed him among the prize-winners, i.e. equal sixth with Réti. He did not defeat Réti or Colle; nor did he play in the first three rounds any of the masters named by Koltanowski. About the alleged ‘Committee’, we know nothing, but it may be wondered who would put together £100, or any other sum, so that W.W. could win ‘with great ease’ a tournament which included Bogoljubow, Marshall, Nimzowitsch, Réti, Tartakower and Vidmar. Moreover, £100 (the amount which, Koltanowski alleges, was spent on alcohol consumption within three days) was then roughly $500, not $350. In today’s money it would come to over $5,000. Finally, the first prize in the tournament was not £100 but £50 (BCM, August 1927, page 335).

Thus every verifiable ‘fact’ in Koltanowski’s yarn is false. Why? Was he guilty, once more, of ‘mere’ sloppiness and doltishness (page 341 of the September 1922 BCM was certainly inspired when it spelt his name ‘Klotanowski’) or was there also a darker side to his compulsive fabrications? William Winter was indeed known to drink heavily, but what sort of human being would, in ‘one of the best chess stories I know’, publicly ridicule a deceased master for alcoholism without making the remotest effort to be truthful?

William Winter

(3624)

As noted on page 228 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves (an item originally published by us in Kingpin in 1995), almost a quarter of the entry on Bogoljubow in The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks (London, 1970) was devoted to the well-known anecdote about how the master, beer mug in hand and looking out of place, was cut from a photograph. Sunnucks’ book stated that this had occurred in Switzerland, but other secondary sources were quoted by us which gave Spain and England. We also reported that the story had appeared on page 13 of CHESS (14 September 1935):

That, in fact, is the first appearance recalled by us, and it may be added here that the following year CHESS (14 November 1936, page 85) described it as ‘the joke about Bogoljubow which Koltanowski contributed to the first number of CHESS’.

Was it really no more than a ‘joke’? That is certainly not the impression given by, for instance, Koltanowski’s rifacimento of his story (‘a ten-board simultaneous blindfold exhibition against all the members of a small chess club in Switzerland’) on page 13 of Chessnicdotes 1 (Coraopolis, 1978). Finally, a discrepancy which we are unable to explain is that pages 28-29 of the 1936 edition of Chess Pie comprised an advertisement for CHESS which featured ‘some extracts’ from ‘the magazine that has taken the chess world by storm’. These included the Bogoljubow story but not only in a different wording but even with a switch from Switzerland to Spain:

(4192)

‘Efim Bogoljubow (1899-1952) was a chubby, bombastic drunkard known for his delusional thinking that he was invincible ...’

That comes from the very start of King’s Gambit by Paul Hoffman (New York, 2007), page ix. (‘1899’ is the book’s first date and is a decade out.)

(5273)

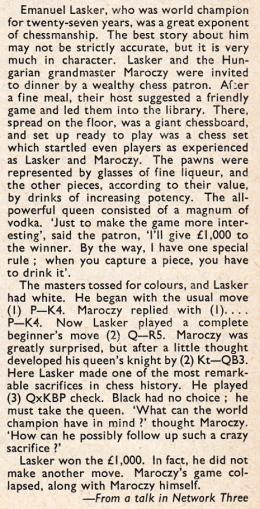

C.N. 3196 (see A Chess Database) mentioned the moves 1 e4 e5 2 Qh5 Nc6 3 Qxf7+, and there are many versions of the related story involving Emanuel Lasker. One ‘is-said-to’ example comes from page 90 of A History of Chess by Jerzy Giżycki (London, 1972):

‘Lasker is said to have won a game of “Alcoholic Chess” by sacrificing his queen in ridiculous fashion at the very outset of the game. The queen contained about a quarter litre of cognac; quaffing this seriously incapacitated his opponent in the ensuing complications – B.H. Wood.’

Page 283 of the August 1959 CHESS had an account reproduced from a chess programme on BBC radio:

How far back can the story be traced? We recall an editorial account of a lunch with G. Koltanowski, one of the least reliable of all chess chroniclers, on page 255 of the November 1938 Chess Review:

(8871)

In his Field column on 24 January 1880 Steinitz reproduced a paragraph from the Daily Telegraph, 7 January 1880 about an ‘extraordinary’ case involving chess and alcohol. We do not have that original publication but can show what appeared in the Leeds Times three days later, i.e. on page 7 of the 10 January 1880 edition:

(9242)

From page 72 of Championship Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1938):

‘Blackburne showed how a chessplayer could drink, poor Mason, on the other hand, how one chessplayer would drink.’

Addition on 3 June 2021:

Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) has sent us this cutting (Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, 29 August 1959, page 15):

An addition from John Townsend (Wokingham, England) dated 21 June 2024:

‘The New York Herald suggested that during the 1843 match in Paris between St Amant and Staunton the latter’s “second” was afraid of the English champion’s partiality to drink and took steps to prevent it damaging his performance. Thanks are due to Jerry Spinrad of Nashville, Tennessee for two quotations from the Herald. He urges caution in evaluating the articles, as they come from a distant source. They are available through the Library of Congress website Chronicling America.

The first is from page 2 of the issue of 8 January 1844:

“Each of the players has a second. Mr Staunton’s man has no sinecure, being obliged to keep a careful watch over him, and to lock him up every evening, so that his faculties might not be impaired through excesses, to which he is rather frequently liable, not having had, till now, any connection whatever with Father Mathew.”

In fact, there were two seconds: Harry Wilson, a lieutenant in the Royal Navy, and John Worrell, a registrar of births. (For some biographical notes on the seconds, see pages 65-66 of my book Notes on the Life of Howard Staunton.)

“Father Mathew” is a reference to Theobald Mathew, an Irish priest, the leader of a temperance campaign.

The remarks about Staunton’s drinking call to mind two incidents related to the match.

Firstly, on the eve of the match the English contingent absented itself from a banquet, which the French found unsociable. It is open to the suggestion that this decision may have arisen out of a desire to keep Staunton “off the bottle”, but it would only be speculation at this stage.

Secondly, Staunton’s success at the board certainly went downhill after Wilson left Paris during the second half of the match, but it must, surely, be an impossible task to link that to consumption of alcohol. Von der Lasa, writing after Staunton’s death, attributed the second-half decline to a different cause, namely, heart trouble (See the City of London Chess Magazine, February 1875, page 12.) It is not clear that either explanation contains any truth.

Mr Spinrad’s second quotation is from page 1 of the New York Herald, 4 February 1844 and concerns the day when Staunton finally clinched victory:

“The stake was for five thousand francs and all expenses; but the bets were much heavier; nearly all the betters were English. Mr Staunton, who was kept on small allowance by his second, got the same evening gloriously drunk. The French papers say, if Mr Staunton is a better chessplayer, at least Mr St Amand [sic] has the advantage of good manners and temperance.”

This passage carries a whiff of anti-Staunton or anti-English sentiment. In a similar vein, an English satirical paper carried vague innuendo of skulduggery in the betting on the match; for which see C.N. 11568.

In Le Palamède, 1843 (page 548), the French writer Alphonse Delannoy, commenting on the dinner that evening, observed that the wine had a Jekyll and Hyde effect on Staunton, turning a serious-minded chessplayer into a pleasing companion; he did not specifically mention a want of sobriety:

“Sous l’inspiration du bordeaux et du champagne, sa physionomie dépose entièrement l’austère sévérité qu’elle a devant l’Echiquier; elle s’illumine d’une franche gaîté, d’une expression tout-à-fait française et de cette animation que donne la satisfaction de l’amour-propre.”

The question of “good manners” is a familiar one if seen as part of being a gentleman – a somewhat slippery term in that age. It is a recurring theme in Staunton’s life and an aspect of his character later questioned by St Amant. As to Staunton’s last night in Paris, no articles have so far been found in the French press which refer to the “good manners and temperance”, or otherwise, of either player.

Notes on the Life of Howard Staunton contained a few references to his use of alcohol. Pages 154-155 described an occasion in 1872 when he visited a friend’s house and was drunk before dinner, blaming the strength of the sherry and his friend for tempting him with it. He refers to having been able formerly “to carry two or three bottles of wine ... discreetly”, but cannot do so since his “late illness”. He adds that two or three glasses are as much as he usually takes and are quite as much as are good for him. “My tippling days are over.”

On page 165, a letter is discussed, written only two or three weeks before his death, in which he remarks that he has given up his “favourite tipple” since giving up his house “and taken to humble malt”. The “favourite tipple” is not specifically identified, but seems to have been a variety of Scotch whisky.

A remark (on page 171) from an obituary written by R.B. Wormald, which appeared in the Westminster Papers, 1 August 1874, refers to his use of “grog”, which may perhaps be taken as being consistent with whisky (even though its original meaning was rum):

“He was great at a dinner party, but greater far when seated behind a long “Broseley” and a modest measure of grog, in company with one or two congenial spirits.”

Staunton was fond of claret. In a letter dated 24 March 1873 (Edinburgh University Library, Special Collections, Letters to J.O. Halliwell-Phillipps, 200/33), he writes at the time of expecting delivery of an item of poultry as a present from his friend:

“The Prarie [sic] Bird has not flown hither yet, but when her henship comes she shall speedily be déplumé, and sent to the spit. Her after progress shall be facilitated by a bumper of G. & M.’s dinner Claret from which a libation will certainly not be forgotten to the health of the Prarie [sic] bird’s donor.”

It seems that in his later days claret at the dinner table in the Staunton household was reserved for special occasions. That view is strengthened by his remark to Halliwell-Phillipps in a letter of 29 August 1873 (Edinburgh University Library, Special Collections, Letters to J.O. Halliwell-Phillipps, 69/37):

“My cake and ale days I fear are over, but if I surmount present troubles & ever crack another bottle of claret, may it be with you!”

In summary, Howard Staunton’s drinking habits later in life were generally moderate, and he was conscious that there were health hazards. There is some evidence that he was a heavy drinker in his younger days, but it is not clear whether that was confined to special occasions, or to what degree his consumption differed from that of his contemporaries, or whether it was ever a problem.’

See too Alekhine and Alcohol.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.