Edward Winter

Introductory note (15 July 2023): Ever since the present article first appeared online it has begun with our contribution on pages 68-70 of the 2/1989 New in Chess (starting with the words ‘In March 1941 ...’). Now we have decided to give first, at the expense of a little repetition, the integral texts of pre-1989 C.N. items on the subject (C.N.s 990, 1021, 1041, 1055, 1168 and 1233).

***

Anthony Saidy (Santa Monica, CA, USA) writes:

‘I recently saw an interview of Euwe, who characterized the writings of Kotov as something like a rich vein of mis- and dis-information. I’ve just read The Soviet Chess School by Kotov and Yudovich, and was momentarily surprised to note its wide variation from the 1958 The Soviet School of Chess by the same authors. This 1983 English-language hardcover from Raduga Publishers, Moscow, appears after Kotov’s demise, so one cannot know how much of it is due to him. It is really a total rewrite, and nearly 200 pages shorter than the 390-page original, which had many chapters on individual stars and a whole section on Alekhine, “Russia’s Greatest Player”. I dare say that Karpov permits no such descriptions any longer! Whereas in 1958 no mention was made of the sticky subject of Alekhine’s petty collaboration with the Nazis in the form of those anti-Semitic essays which I believe were written so ludicrously as to telegraph their insincerity, now we learn that he was “unjustly accused of collaboration”. I believe this exculpation to be the most transparent rewriting of history for the hackneyed Soviet ideological purposes. When I pointed out to Kotov at Nice in 1974 the fact that a leading British figure had, after Alekhine’s death, found a version of the essays in his handwriting (– where are they now? –), thus proving their authenticity, if not their plausibility, he brushed it off as “British propaganda”. Without doubt, Alekhine was a bit anti-Semitic (most people were) but that didn’t deter him from engaging a Jewish second, Landau, as Euwe told me, or from being pals with Denker, who tried to stop Fine’s post-war move to strip Alekhine of his title for political reasons. (I suppose this is apposite to Fine’s current suggestion to split FIDE and name a “Free World Champion”, Fischer – how ironic that he nominates one with known anti-Semitic views!). This terrible century seems to drive mad those whom it hasn’t yet killed.’

(990)

From Harry Golombek (Chalfont St Giles, England) – for the full text of his letter to us, dated 7 July 1985, see Harry Golombek (1911-95):

‘When Alekhine’s widow died Brian Reilly was in Paris and he was afforded the opportunity of examining her effects. When he returned from Paris he said to me sadly, “It’s true about the Alekhine anti-Semitic articles. I’ve seen them in Alekhine’s own handwriting”.

However, I should add that Reilly, who is writing a definitive biography of Alekhine and for whom Alekhine seems to have become a sort of chevalier sans peur et sans reproche, said to me a few months ago, “Where did you get the information in your article in your encyclopedia about Alekhine having written the anti-Semitic articles?”

Upon my telling him that I had got the information from him on his return from Paris, he denied that any such conversation had taken place. So you have to take your choice; either my memory is right (and I can still see in my mind’s eye Brian’s melancholy face as he told me this) or Brian’s memory is right and this never took place. I must add that most people find my memory is all right; nor do I experience any difficulty in remembering the appropriate facts for writing an article about something about 20 years ago.’

(1021)

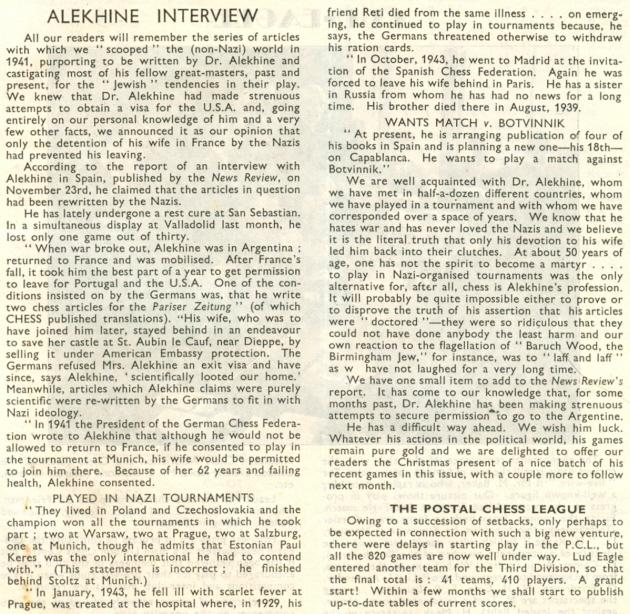

It is sometimes implied, or even stated, that Alekhine did not deny authorship of the anti-Semitic articles until after the War was over. Note, however, this report in the January 1945 CHESS (page 53):

‘We knew that Dr Alekhine had made strenuous attempts to obtain a visa for the USA and, going entirely on our personal knowledge of him and a very few other facts, we announced it as our opinion that only the detention of his wife in France by the Nazis had prevented his leaving.

According to the report of an interview with Alekhine in Spain, published by the News Review, on 23 November, he claimed that the articles in question had been rewritten by the Nazis.’

A letter from Bernstein dated 5 October 1945 and published in the November 1945 CHESS (pages 28-29) has the following strong words about Alekhine:

‘My profound attachment to chess restrains me from telling all I think of Alekhine, since the fall of France. In May 1940, I played against him in Paris (a so-called “consultation” game) and won. I could not have guessed that he would behave afterwards as he did. I shall never play against him again and I do not even wish to see him. I refused to meet him at Barcelona, when he visited that city to give chess exhibitions.

I think that the above makes my conception of “collaboration” clear.

The chess world is aware of the tragic end of the grand Polish chessmaster and composer Dawid Przepiórka who was condemned to death for having entered a café where chess was played; he was forbidden to do that, because he was a Jew. But it is not generally known that Alekhine, though on close terms with the Nazi Governor of Poland, Dr Frank, with whom he was photographed for Nazi periodicals published at the time, refused to intervene to secure Przepiórka’s release. This fact of his non-intervention was told me by Sämisch when he came to Barcelona at the end of 1943. I could also mention articles published by Alekhine after 1940 and the chess exhibitions he gave to entertain the Nazi Forces. I refrain from giving further disgusting details about his behaviour. It could be added that he adopted the Nazi salute “Heil Hitler” with outstretched arm. I am fully aware of what my statements mean but I consider it my moral duty and I leave it to you to make conclusions.’

Alekhine replied in the January 1946 issue.

‘As for Dr Bernstein’s “information”, I can only state that my friend D. Przepiórka was murdered before the end of 1939 [sic] (I heard the narrative of his [sic] from an eye-witness) and it is known that I played in Germany and Poland only from the end of 1941. What connection could I have with this tragical event??

I may add that the game Dr Bernstein gives was played at my home and had an absolutely private character – but of course this has no importance at all.’

The Editor of CHESS added:

‘Dr Alekhine goes on to say that he has been very sick this year but had to go on playing, or starve. He has had a rest at Tenerife and is feeling much better, but ill-health and worry have sapped his playing ability.’

From the May 1946 CHESS, page 172:

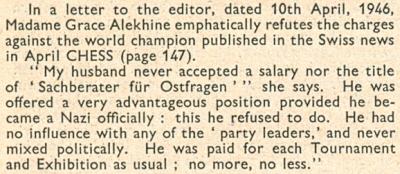

‘In a letter to the editor, dated 10 April 1946, Madame Grace Alekhine emphatically refutes the charges against the world champion published in the Swiss news in April CHESS (page 147).

“My husband never accepted a salary nor the title of ‘Sachberater [sic] für Ostfragen’”, she says. “He was offered a very advantageous position provided he became a Nazi officially: this he refused to do. He had no influence with any of the ‘party leaders’, and never mixed politically. He was paid for each Tournament and Exhibition as usual; no more, no less.”’

(1041)

A footnote on the Nazi articles, often talked about, rarely read. I.A. Horowitz and P.L. Rothenberg’s The Complete Book of Chess (formerly entitled The Personality of Chess) publishes a ‘certified translation’ of some of what Alekhine allegedly wrote, though not all, as is perhaps implied. For the full texts (as far as we know) the best source is a 1983 booklet by Griessharnmer Verlag of Nuremberg, Aljechin, Jüdisches and arisches Schach.

Schlechter has sometimes been referred to as a Jew, though our understanding is that he was not. One denial appeared in a contemporary Deutsche Schachzeitung and was quoted in The Complete Book of Chess, page 252. Then on page 254 Alekhine is claimed to have written: ‘Founded by the Jew Max Weiss, and fostered later on by the Jews Kaufmann and Fähndrich, this School saw the secret of success not in winning, but in not-losing.’ However, in the German source there is: ‘Wiener Schule (welche das Geheimnis des Erfolges nicht im Siege, sondern im Nichtverlieren erblickte), gegründet von dem Juden Max Weiss, und später propagiert von dem Judentrieo Schlechter-Kaufmann-Fähndrich, die Weltschachbühne beherrschte.’

At what stage did Schlechter’s name drop out, and how many other discrepancies are to be found in comparing the various ‘original’ and translated versions that have been published?

(1055)

Rob Verhoeven (The Hague, the Netherlands) sends us photocopies of the relevant pages from Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden and Deutsche Schachzeitung. The former speaks of a ‘Jewish trio’ but the latter names only Kaufmann and Fähndrich.

Our guess would be that when reprinting the article Deutsche Schachzeitung itself took out Schlechter’s name because, as stated elsewhere in one of its footnotes, it did not believe him to be Jewish.

Ken Whyld (Caistor, England) informs us that he is working on an English translation of the articles and that he will indicate variations and additions. This will be an invaluable document that should clear up such discrepancies as the above once and for all.

(1168)

The controversy over whether Alekhine wrote the Nazi articles regularly attributed to him has generally been conducted in ignorance of the actual complete texts, a common fallacy being that Horowitz and Rothenberg’s The Personality of Chess provides them. But now the booklet by Ken Whyld mentioned in C.N. 1168 is available (from, among others, the BCM). The new English translation appears on the left-hand pages; opposite are notes on variants, discrepancies, etc. Ken Whyld has preferred to keep his commentary to a minimum, leaving the reader to reach his own conclusions; we slightly regret this, given the high quality of the observations he does provide. To the key question of whether Alekhine was indeed the author no answer is proffered, but five possibilities are listed:

1) he wrote none of it;

2) he wrote a harmless historical survey to which someone added the propaganda without his knowledge;

3) as 2) but with his knowledge;

4) he wrote it all but tried to signal his insincerity by including absurd statements;

5) he wrote it and meant it.

Possibility 4) is currently quite popular, but if that had really been Alekhine’s intention, would he not have made deliberate gaffes about his own life? We see none. There are countless ‘inexplicable’ misspellings (a number of times Marshall is spelt Marschall, for example) but these could easily have been the fault of a German typesetter.

In fact, though, we would suggest a sixth possibility as the most likely of all: Alekhine wrote everything, but simply because it was expedient. Not all writers necessarily believe everything they write; some have few qualms about what appears over their name. They may be indifferent to the reader’s reaction, or count on public forgetfulness, or they may have sufficient self-confidence, or arrogance, to trust in their ability to extricate themselves in the (relatively unlikely) event of being challenged. It could be argued that arrogance, lack of a sense of danger and indifference to possible repercussions were indeed traits of Alekhine’s character. Certainly he never seems to have worried about being caught out over score-tampering or his non-existent doctorate, and, as far as we recall, during his lifetime he never was. [On this last point see, however, C.N. 1842 in Chess Jottings.]

The questions remain. Was Alekhine really sufficiently fluent in German to write such material? Why did the articles first appear in minor newspapers rather than being sold as a scoop to a higher-paying major outlet? How to explain the curious editorial attitude of the Deutsche Schachzeitung when it reprinted (most of) the material? Did Alekhine imagine that the articles would appear only in small, instantly forgotten, newspapers? Why did Mme Alekhine apparently not destroy the copies before her own death in 1956? What exactly were these copies (handwritten doubles?) and, the key question, where are they now?

The articles have prompted much nonsense from chess writers, an example being Pachman’s suggestion on page 11 of Checkmate in Prague that they accused Jews of cheating at chess. It ought to be possible to find the articles appalling without misrepresenting their contents or over-earnestly condemning every word of every sentence. Ken Whyld has ensured that everybody can, at last, debate the matter en connaissance de cause.

(1233)

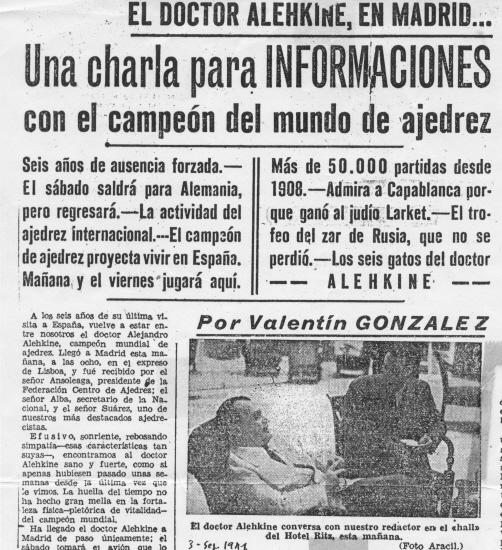

Pablo Morán (Gijón, Spain) sends us copies of two Madrid publications dated 3 September 1941 in which Alekhine gave interviews. Both are illustrated with a photograph of the world champion in conversation with the respective interviewers.

[The full texts were then given, in our translation, and they can also be found in Two Alekhine Interviews (1941).](1455)

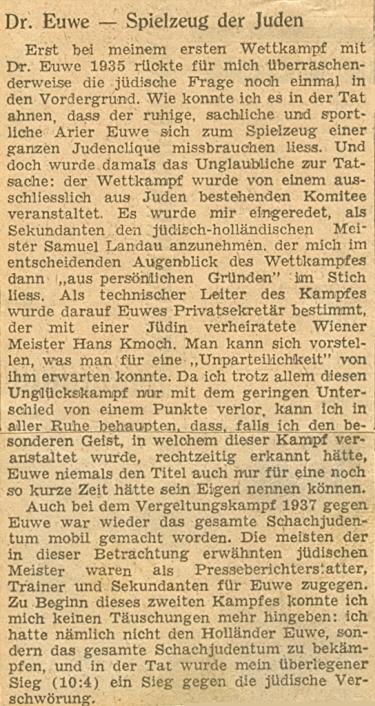

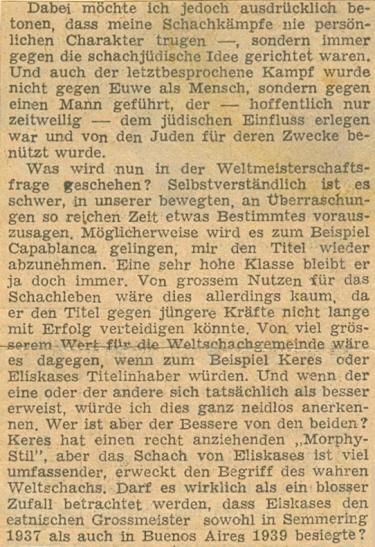

In March 1941 a series of articles under the name of Alexander Alekhine appeared in Pariser Zeitung, a newspaper published in the French capital by the occupying German forces. Entitled ‘Aryan and Jewish Chess’, the articles claimed that Jews had had a destructive effect on the development of the game. Three brief extracts will give the flavour:

Much of the material was subsequently reprinted, though with considerable textual variants, in Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden and Deutsche Schachzeitung. The magazine CHESS printed extensive English translations (of the Deutsche Schachzeitung version), as did Horowitz and Rothenberg’s 1963 book The Personality of Chess. However, it was not until 1986 that a complete English version of the original Pariser Zeitung articles became available (Alekhine Nazi Articles, an excellent privately printed booklet edited by Kenneth Whyld). In recent years there have also been two reproductions of the original German, by Wolfgang Kubel (1973) and Herbert Griesshammer (1983).

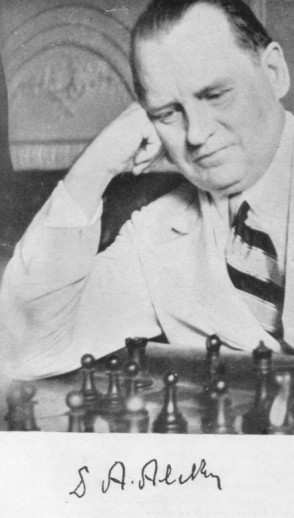

An extract from Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden

Condemnation of the articles came from many notable sources. The November 1945 CHESS (page 28) quoted from De Waarheid a denunciation of Alekhine by G.C.A. Oskam: ‘His libellous articles have filled me with sorrow. They were written by a miserable collaborator, by a mean profiteer; they breathe lies and fraud, the necessary elements of racial hatred; they are dictated by the qualities present in the person of a double traitor ...’ The same magazine published an anti-Alekhine letter from Ossip Bernstein which was not without over-the-fence gossip: ‘I refrain from giving further disgusting details about his behaviour. It could be added that he adopted the Nazi salute “Heil Hitler” with outstretched arm.’

Alekhine’s first disavowal of the articles appears to date from just after the liberation of Paris (and not from just after the end of the War, as sometimes alleged even today). The December 1944 BCM (pages 274-275) and the January 1945 CHESS (page 53) both reported Alekhine’s statement in a published interview (News Review, 23 November 1944 was the source according to CHESS) that while in France ‘he had to write two chess articles for the Pariser Zeitung before the Germans granted him his exit visa ... Articles which Alekhine claims were purely scientific were rewritten by the Germans, published and made to treat chess from a racial viewpoint.’

After his invitation to the London, 1946 tournament was withdrawn because of his war record, Alekhine wrote a long open letter to the organizer, W. Hatton Ward, which was widely published at the time. With regard to the articles, he stated:

‘Among the heap of monstrosities published by the Pariser Zeitung appeared insults against the members of the Committee which organized the 1937 match: and the Dutch Chess Federation even lodged a protest on this matter with Post. At that time I was absolutely powerless to do the one thing which would have clarified the situation, to declare that the articles had not been written by me ... For three years, until Paris was liberated, I had to keep silent. But from the first opportunity I tried in interviews to show up the facts in their true light. Of the articles which appeared in 1941 during my stay in Portugal and which I learnt about in the Deutsche Schachzeitung, nothing was actually written by me. I had submitted material dealing with the necessary reconstruction of the FIDE (the International Chess Federation) and a critique, written well before 1938, of the theories of Lasker and Steinitz. I was surprised when I received letters from Messrs Helms and Sturgis at the reaction which these articles – purely technical – had provoked in America and I replied to Mr Helms accordingly. Only when I knew what incomparably stupid lucubrations had been created in a spirit imbued with Nazi ideas did I realize what it was all about. But I was then a prisoner of the Nazis and our only hope of preservation was to keep silent. Those years ruined my health and my nerves and I am even surprised that I can still play chess.’

(The above is the CHESS translation. In the BCM Helms came out as ‘Helsus’ and ‘1939’ was given rather than 1938.)

Alekhine wrote a further denial on page xx of his last book, the posthumous ¡Legado!:

‘Once more I insist on repeating that which I have published on several occasions: that is, that the articles which were stupid and untrue from a chess point of view and which were printed signed with my name in a Paris newspaper in 1941 are a falsification. It is not the first time that unscrupulous newspapers have abused my name in order to publish inanities of that kind but in the present case what was published in Pariser Zeitung is what has caused me the most grief, not only because of its content but also precisely because it is impossible for me to rectify it ... Colleagues know my sentiments and they know perfectly well how great is the esteem in which I hold their art and that I have too elevated a concept of chess to become entangled in the absurd statements poured out by the above-mentioned Parisian newspaper.’

Thus Alekhine’s line of defence was not consistent. Sometimes he claimed to have written nothing, but on other occasions said that the anti-Jewish slant had been added by others. The latter possibility is unlikely; once the anti-Jewish slant is taken away there is hardly anything left.

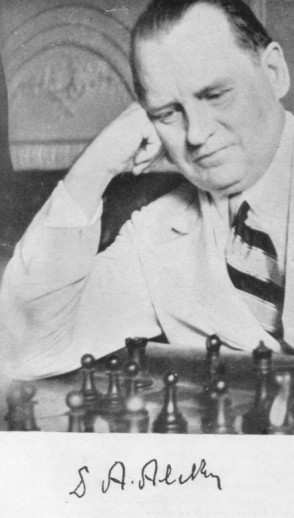

Alexander Alekhine

Two widely-read reference books, Golombek’s The Encyclopedia of Chess (London, 1977) and Hooper and Whyld’s The Oxford Companion to Chess (Oxford, 1984), state that upon the death of Alekhine’s widow in 1956 the articles were found in Alekhine’s own handwriting. In both cases the authors subsequently gave their source for this information: Brian Reilly, then the Editor of the BCM, had told them in 1956 that he had just seen the articles. However, this is denied by Reilly, whose eagerly-awaited biography of Alekhine will doubtless provide his account of the matter. [Brian Reilly died in 1991, and his work on Alekhine has not been published.] Another alleged sighting of the articles also has a curious twist. In the May 1986 Europe Echecs (pages 300-301) Jacques Le Monnier reported that before her death Grace Alekhine had passed a number of her late husband’s notebooks to a friend (unnamed). In 1958 Le Monnier was given access to the material and found, word for word and in Alekhine’s own handwriting, the text of the first anti-Semitic article, which had appeared in Pariser Zeitung of 18 March 1941. The word ‘Jew’ was almost invariably underlined, Le Monnier reported. This testimony seems watertight until one compares it with what Le Monnier wrote about the articles on page 24 of his 1973 book 75 parties d’Alekhine: ‘Alekhine stated several times that “not a word had been written by him”. It will never be known whether Alekhine was behind these articles or whether they were “manipulated” by the editor of the Pariser Zeitung, a Czech player well known at the time in Parisian chess circles.’ These are, to say the least, surprising words from someone who, a dozen or so years later, was to declare that he himself had seen one anti-Semitic article in Alekhine’s own handwriting. (In passing it may also be wondered why Alekhine and his wife refrained from destroying such incriminating material as may have been in their possession after the fall of the Third Reich.)

Such inconsistencies will be welcomed by defenders of Alekhine, many of whom have suggested that, being forced, for his own and his wife’s safety, to write anti-Semitic material, the then world champion deliberately made it ridiculous and inaccurate. The original Pariser Zeitung publication contained many elementary misspellings of proper names (‘Marschall’, ‘Andersen’, ‘Pilsburry’, etc. ). There is a reference to the match between La Bourdonnais and ‘Macdonald’ (instead of McDonnell) and to a ‘Polish Jew’ named ‘Kienezitzky’. (Kieseritzky is meant, although he was apparently neither Polish nor Jewish.) Some mistakes were corrected in the Deutsche Schachzeitung reprint, as were factual errors like the suggestion in Pariser Zeitung that Schlechter was a Jew. But the theory that Alekhine tried to signal his insincerity is mere guesswork which is not even supported by any claim to that effect from Alekhine himself. The wrong spellings might just as easily be put down to a Pariser Zeitung typesetter’s difficulty in reading Alekhine’s idiosyncratic handwriting.

Fresh documentation has recently come to light which considerably strengthens the case against Alekhine. Pablo Morán has discovered two Madrid publications dated 3 September 1941 which contain interviews given by Alekhine just before his departure for the Munich, 1941 tournament. El Alcázar reported:

‘He [Alekhine] added that in the German magazine Deutsche Schachzeitung and the German daily Pariser Zeitung, currently published in Paris, he had been the first to deal with chess from the racial point of view. In these articles, he said, he wrote that Aryan chess was aggressive chess, that he considered defence solely to be the consequence of earlier error, and that, on the other hand, the Semitic concept admitted the idea of pure defence, believing it legitimate to win this way.’

Alekhine told Valentín González of Informaciones about his intention to give lectures ‘about the evolution of chess thought in recent times and the reasons for this evolution. There would also be a study of the Aryan and Jewish kinds of chess.’ Moreover, Alekhine was quoted as saying that he was not in favour in the United States and England ‘as a result of some articles I wrote in the German press and some games I played in Paris during the last winter – against 40 opponents – for the German Army and Winter Relief.’ When asked which players he most admired Alekhine’s published reply was: ‘... I must stress the greatest glory of Capablanca, which was to eliminate the Jew Lasker from the world chess throne.’

The Nazi articles affair is one of chess history’s most notorious scandals and intriguing mysteries. Although, as things stand, it is difficult to construct much of a defence for Alekhine, only the discovery of the articles in his own handwriting will settle the matter beyond all doubt.

The above article first appeared on pages 68-70 of the 2/1989 New in Chess. On page 6 of the 4/1989 issue Jacques Le Monnier made a brief reply. It consisted of a fuller extract from the Europe Echecs article in which he had said that he had seen an article in Alekhine’s own handwriting, as well as the following remark:

‘I would not change a word. Alekhine’s notebooks are private documents and French law is categorical in this respect. They will enter in the public domain 60 years after the author’s death, i.e. in 2006. After this date historians and researchers may consult them, provided that Alekhine’s heirs and the owners of the notebooks agree.’

In C.N. 1920 we quoted this and commented: ‘It is a pity that Mr Le Monnier did not answer our straightforward point: if in 1958 he saw an article in Alekhine’s own hand, why, some 15 years later, did he write that ‘it will never be known whether Alekhine was behind these articles …’?

C.N.s 3605, 3606 and 3617 reverted to the Alekhine affair, and the third of these items mentioned that French copyright law changed in the 1990s, with the result that the notebooks would not enter the public domain until 1 January 2017.

Complete English translations of Alekhine’s articles in El Alcázar and Informaciones were given in C.N. 1455 and are available as a separate feature article.

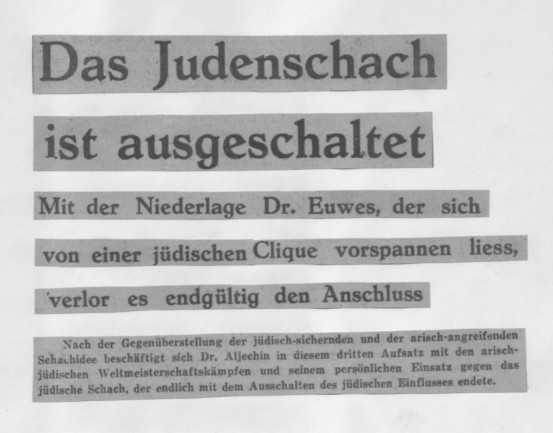

The postcard to us from Brian Reilly referred to in C.N. 3606:

As regards his projected book on Alekhine, Brian Reilly had also written the following to us in a letter dated 10 February 1984:

C.N. 3617 noted that three people, V. Halberstadt, J. Le Monnier and B. Reilly, are on record as having seen the Alekhine ‘Nazi articles’ in his handwriting. Steve Giddins (Moscow) now quotes the following from an article by Boris Spassky on page 14 of Shakhmatnaya Nedelya, March 2005:

‘... a good friend of mine, a retired Canadian professor of mathematics, personally saw Alekhine’s handwritten pages in the archive of Brian Reilly.’

This appears to be another of Spassky’s historical muddlings (see also, for instance, C.N. 3425). In any case, we are aware of no ‘retired Canadian professor of mathematics’ who is capable of making authoritative or reliable statements about Alekhine.

(3660)

It may be recalled from page 281 of A Chess Omnibus that

in an interview with Informaciones (Madrid) published on 3 September 1941 Alekhine was quoted as saying:

‘... trips to the United States or England are out of the question; I am not in favour in those countries, as a result of some articles I wrote in the German press and some games I played in Paris during the last winter – against 40 opponents – for the German Army and Winter Relief.’

Page 655 of Alexander Alekhine’s Chess Games, 1902-1946 by L. Skinner and R. Verhoeven (Jefferson, 1998) stated: ‘After Alekhine’s return to France and his entry into the French Army, almost nothing is known of his chess activities during the spring and summer of 1940.’ (The same page has an unfortunate error about the treatment of French military personnel by the German High Command: ‘many were interred as prisoners of war.’)

The extent to which Alekhine played chess in France on behalf of the German Army and Winter Relief is unknown, but we note that in the early part of 1940 he had proposed to help the war effort of the other side, and was turned down. From page 208 of CHESS, June 1940:

‘World champion’s noble offer. Dr Alekhine offered to play 300 opponents in London simultaneously (in 60 groups of five) in aid of war charities. The BCF declined the offer, stating that it would be “very difficult” to arrange such a display in the near future.’

As indicated on the previous page, that issue of CHESS was published on 20 May 1940, i.e. nearly a month before Paris fell to Nazi Germany. Has the correspondence with Alekhine survived in the British Chess Federation’s archives or elsewhere?

(3717)

João Pedro S. Mendonça Correia (Lisbon) writes:

‘Does anyone have an explanation for the fact that, despite his stature in the chess world, Tarrasch was not attacked by the author of the infamous 1941 articles on Jewish and Aryan chess? I do not believe that his (now confirmed) conversion in 1909 from Judaism to Christianity (C.N. 5997) would be a satisfactory explanation.’

(6067)

We note the following similar claims that Capablanca’s great achievement was to dethrone the Jew Lasker:

Source: ‘Jüdisches und arisches Schach’ article published under Alekhine’s name in the Pariser Zeitung and in the Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden (1941);

Source: interview with Alekhine in Informaciones (1941).

See Two Alekhine Interviews (1941).

(6068)

Regarding the anti-Semitic articles published in 1941 under Alekhine’s name, Henk Smout (Leiden, the Netherlands) writes:

‘The June-July 1942 issue of the Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond reported on a congress in Salzburg (held during a tournament won by Alekhine) concerning the foundation of an “Europaschachbund” (European Chess Federation). At the congress Alekhine was the French representative, and the magazine’s report (page 88) contained the following “rectification”:

“Gedurende dit congres heeft dr Aljechin tegenover den secretaris van den Ned. Schaakbond zijn leedwezen betuigd over het misverstand, dat zich in het afgeloopen jaar heeft voorgedaan als gevolg van een onjuiste publicatie betreffende het dr Euwe-comité, in het bijzonder ten opzichte van dr Euwe en de heeren Van Harten en Liket.”

[“During this congress Dr Alekhine expressed regret to the secretary of the Dutch Chess Organization about the misunderstanding which occurred last year in consequence of an incorrect publication concerning the Euwe committee, and in particular with respect to Dr Euwe and Messrs Van Harten and Liket.”]

This was understandable only to those who knew the Pariser Zeitung of 23 March 1941 or the Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden of 2 April 1941. It related to the final anti-Semitic article, which stated that the organizing committee of the 1935 match with Euwe had consisted exclusively of Jews and that Euwe was a plaything of the Jews.

That article was not included in the Deutsche Schachzeitung’s serialization. The German magazine’s last instalment concluded on pages 82-84 of the June 1941 issue, and the promise “Fortsetzung folgt” was left unfulfilled, without explanation. It may, though, be relevant that Euwe had long been listed by the Deutsche Schachzeitung as a contributor. (He also became a “Mitarbeiter” of the Deutsche Schachblätter, the official organ of the Grossdeutscher Schachbund, as from the April 1941 issue.)

Approximately 40% of the text of the anti-Semitic articles was not republished in the Deutsche Schachzeitung and was therefore also absent from CHESS, which printed an English translation of what had appeared in the Deutsche Schachzeitung.’

Below we reproduce from our collection the relevant part of the article as it appeared in the Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden:

(6110)

Addition on 19 March 2022:

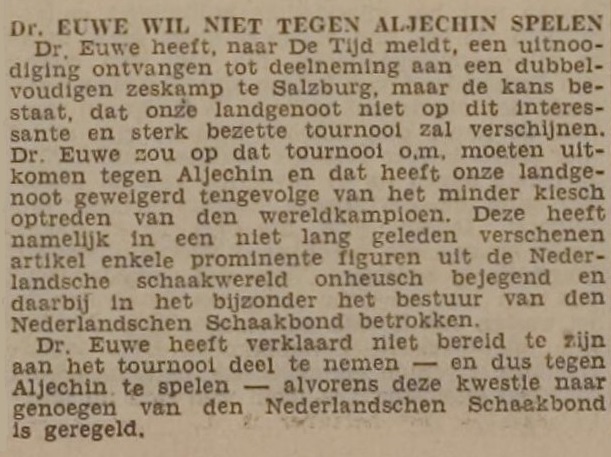

Mr Smout adds a report on page 2 of the Leidsch Dagblad, 14 November 1941 that Euwe was not prepared to play against Alekhine until the the issue of the latter’s quoted remarks about Dutch players and the Dutch Federation had been satisfactorily resolved:

‘The best argument in support of Alekhine’s later contention that the articles were forgeries is that, wholly apart from their being hateful, they are utterly inane, but Alekhine’s denial that he was the author was not enunciated until March 1946; by that time, the movement to ostracize him had already gained considerable support. An invitation to the tournament at London in January of 1946 was withdrawn at the insistence of the United States federation, and there were suggestions from several quarters that he be somehow stripped of his title.

Alekhine defended himself in an open letter to the editor of the Australian magazine Chess World, in which he stated that “of the articles which appeared in 1941 during my stay in Portugal ... nothing was actually written by me”.’

Source: page 119 of The World Chess Championship A History by Al Horowitz (New York, 1973).

The open letter was written not to the editor of Chess World (C.J.S. Purdy) but to W. Hatton Ward, the organizer of the London, 1946 tournament; Purdy merely reproduced the letter in the 1 March 1946 issue of his magazine (pages 26-27). See also pages 263-267 of The Personality of Chess (New York, 1963), a book which Horowitz co-authored with P.L. Rothenberg.

Alekhine’s letter was written from Madrid on 6 December 1945, but Horowitz’s error over the timing of a denial (‘not enunciated until March 1946’) is more significant than that. As mentioned in our feature article (see above), the first disavowal by Alekhine appears to date from just after the liberation of Paris. The December 1944 BCM (pages 274-275) and the January 1945 CHESS (page 53) reported Alekhine’s statement in a published interview (News Review, 23 November 1944 was the source given in CHESS) that while in France (to quote the BCM text) ‘he had to write two chess articles for the Pariser Zeitung before the Germans granted him his exit visa ... Articles which Alekhine claims were purely scientific were rewritten by the Germans, published and made to treat chess from a racial viewpoint.’

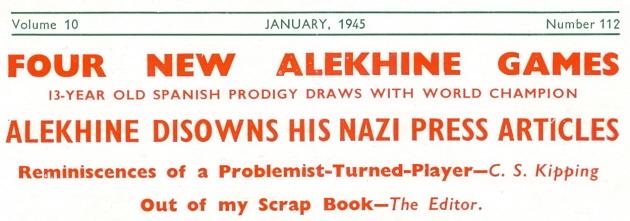

Below is part of the front cover of the January 1945 CHESS (published in December 1944):

From page 53 of the same issue:

Does any reader have the full original interview in News Review?

Other writers have erroneously claimed that Alekhine did not deny authorship of the articles until after the War. See, for example, page 198 of Grandmasters of Chess by H. Schonberg (Philadelphia and New York, 1973) and page 174 of The World of Chess by A. Saidy and N. Lessing (New York, 1974). The fact that Alekhine made a public denial some five months before the Third Reich fell is, of course, open to discussion in terms of its political and practical significance, but it is still a fact, and one often ignored.

(6274)

As reported in C.N. 1041, a letter from Ossip Bernstein dated 5 October 1945 and published in the November 1945 CHESS (pages 28-29) condemned Alekhine:

‘My profound attachment to chess restrains me from telling all I think of Alekhine, since the fall of France. In May 1940, I played against him in Paris (a so-called “consultation” game) and won. I could not have guessed that he would behave afterwards as he did. I shall never play against him again and I do not even wish to see him. I refused to meet him at Barcelona, when he visited that city to give chess exhibitions.

I think that the above makes my conception of “collaboration” clear.

The chess world is aware of the tragic end of the grand Polish chessmaster and composer Dawid Przepiórka, who was condemned to death for having entered a café where chess was played; he was forbidden to do that, because he was a Jew. But it is not generally known that Alekhine, though on close terms with the Nazi Governor of Poland, Dr Frank, with whom he was photographed for Nazi periodicals published at the time, refused to intervene to secure Przepiórka’s release. This fact of his non-intervention was told me by Sämisch when he came to Barcelona at the end of 1943. I could also mention articles published by Alekhine after 1940 and the chess exhibitions he gave to entertain the Nazi Forces. I refrain from giving further disgusting details about his behaviour. It could be added that he adopted the Nazi salute “Heil Hitler” with outstretched arm.

I am fully aware of what my statements mean, but I consider it my moral duty and I leave it to you to make conclusions.’

Alekhine’s reply was given on page 76 of the January 1946 issue:

‘Dr Alekhine informs us that the attacks quoted in CHESS of Dr Oskam, who was always his friend, were particularly painful to him.

“As for Dr Bernstein’s ‘information’, I can only state that my friend D. Przepiórka was murdered before the end of 1939 (I heard the narrative of his [sic] from an eye-witness) and it is known that I played in Germany and Poland only from the end of 1941. What connection could I have with this tragical event??

I may add that the game Dr Bernstein gives was played at my home and had an absolutely private character – but of course this has no importance at all.”

Dr Alekhine goes on to say that he has been very sick this year but had to go on playing, or starve. He has had a rest at Tenerife and is feeling much better, but ill-health and worry have sapped his playing ability.’

Regarding Przepiórka, it is believed that he was killed in April 1940 (see C.N. 6618).

(7181)

The text of C.N. 2238:

As far as is known, Dawid Przepiórka died in a concentration camp in Poland in early 1940. We quote without comment the (full) announcement of his death on page 39 of the March 1942 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

‘From South America comes the news that the composition artist [Aufgabendichter] D. Przepiórka died some time ago. He was 62 years old.’

See too our feature article Dawid Przepiórka, as well as Hans Frank and Chess.

The accusation that Alekhine did not intervene on behalf of Dawid Przepiórka was rebutted in a footnote to Alekhine’s obituary on page 87 of the June 1946 Revue suisse d’échecs:

‘Le reproche de ne pas être intervenu en faveur du maître Przepiórka en 1942, lors de son séjour à Varsovie, est infondé. On sait maintenant, par des témoignages récents venant de la capitale polonaise, que le grand maître et compositeur polonais tomba victime de la persécution anti-juive en 1940 déjà, donc deux ans avant la visite d’Alekhine.’

The obituary was written by Erwin Voellmy and Jean-Charles de Watteville, and page 84 had a woodcut of Alekhine by Voellmy:

(7182)

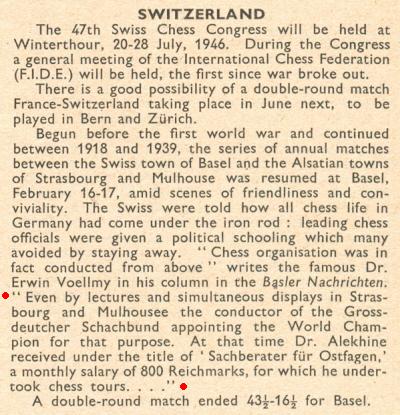

Page 147 of the April 1946 CHESS reported a claim by E. Voellmy that Alekhine was a paid consultant of the Nazis:

As mentioned in C.N. 1041, Alekhine’s widow denied the Sachberater für Ostfragen charge on page 172 of the May 1946 CHESS:

(7183)

Two correspondents in Paris, Christophe Bouton and Denis Teyssou, inform us that they have created a webpage concerning notebooks written by Alekhine towards the end of his life.

Future C.N. items will revert to a number of matters, but for now we invite readers to peruse the material presented so far. It is not to be missed.

(8060)

On page 178 of Chess The History of a Game (London, 1985) Richard Eales wrote:

‘Under pressure from the German authorities, Alekhine even lent his name to two articles in the Pariser Zeitung during 1941 ...’

In a superficial general article entitled ‘Politics and Chess’ on pages 8-10 of History Today, September 1993, Eales stated:

‘... Alexander Alekhine, himself a Russian emigré [sic], was persuaded in 1941 to publish articles contrasting wholesome Aryan chess and materialistic Jewish chess.’

Such flat assertions are unwise, given that no proof has been found that there was ‘pressure’ or ‘persuasion’.

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) reports that the Gallica site of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France has recently placed on-line a run of the Pariser Zeitung, the newspaper published during the Nazi occupation of France.

The anti-Semitic articles which appeared under Alekhine’s name were printed there in six parts, on 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23 March 1941. The Gallica project lacks the first part in the serialization, but the other five have been drawn together in a file [broken link] by Mr Thimognier, together with an introductory note in the 16 March 1941 edition.

Pariser Zeitung, 19 March 1941, page 3

Our correspondent adds:

‘The newspaper’s chess column was published on Sundays and began on 16 February 1941. Some material was attributed to “A.L.”, who was identified on 23 March 1941 as A. Linder.

In a correction on page 6 of the 27 April 1941 edition the chess column stated that Schlechter was not Jewish:

From July to December 1941, games were usually annotated by Znosko-Borovsky. The reference to “Geleitet von Weltmeister Dr. Aljechin” was dropped with the 7 December 1941 column even though, strange to say, the content subsequently consisted solely of games annotated by Alekhine. In 1942 the column appeared only occasionally, and the last one that I have found is dated 17 May 1942.’

(10085)

William D. Rubinstein (Melbourne, Australia) asks whether further information is now available as to the possible release of the original texts written by Alekhine. In 2005 (C.N. 3617) we wrote:

French copyright law changed in the mid-1990s, and Article L123.1 of the current Code de la propriété intellectuelle provides for a term of 70, not 60, years post mortem auctoris. (Similar amendments of national laws were made throughout the European Union, following on from the ‘Council Directive 93/98/EEC of 29 October 1993 harmonizing the term of protection of copyright and certain related rights’.) In the absence of special circumstances the Alekhine ‘Nazi articles’ will enter into the public domain on 1 January 2017.

(10928)

C.N. 3605 reproduced most of a letter which Harry Golombek wrote to us on 7 July 1985. It included the following:

‘Meanwhile a little clarification about the discovery of the Alekhine articles.

When Alekhine’s widow died Brian Reilly was in Paris and he was afforded the opportunity of examining her effects. When he returned from Paris he said to me sadly, “It’s true about the Alekhine anti-Semitic articles. I’ve seen them in Alekhine’s own handwriting”.

However, I should add that Reilly, who is writing a definitive biography of Alekhine and for whom Alekhine seems to have become a sort of chevalier sans peur et sans reproche, said to me a few months ago, “Where did you get the information in your article in your encyclopedia about Alekhine having written the anti-Semitic articles?”

Upon my telling him that I had got the information from him on his return from Paris, he denied that any such conversation had taken place. So you have to take your choice; either my memory is right (and I can still see in my mind’s eye Brian’s melancholy face as he told me this) or Brian’s memory is right and this never took place. I must add that most people find my memory is all right; nor do I experience any difficulty in remembering the appropriate facts for writing an article about something about 20 years ago.’

In a letter on page 6 of the August 1993 Chess Life, addressed to Larry Evans and correcting him on certain points, Kenneth Whyld wrote:

‘... Brian Reilly died without completing his book on Alekhine. In fact, he had hardly written a word, although he had done a vast amount of research over 17 years and amassed a large number of games. I now have his files and am working on a biography with few or no games ...

There is an enormous amount of new material about Alekhine’s life, and I believe the Reilly/Whyld book will be a revelation ...

Brian Reilly did not deny “ever seeing” the Nazi articles in Alekhine’s handwriting. Indeed, he told the same story to Golombek as well as myself. When we both published his comments, in different places, Reilly was embarrassed and said that while he had seen the books, and confirmed they were in Alekhine’s handwriting, he could not say anything about the contents, because he did not speak German.

In other words, Reilly, who was careful and precise, did not want to be quoted as having verified the text. However, I have other authority for that verification.’

From C.N. 5648:

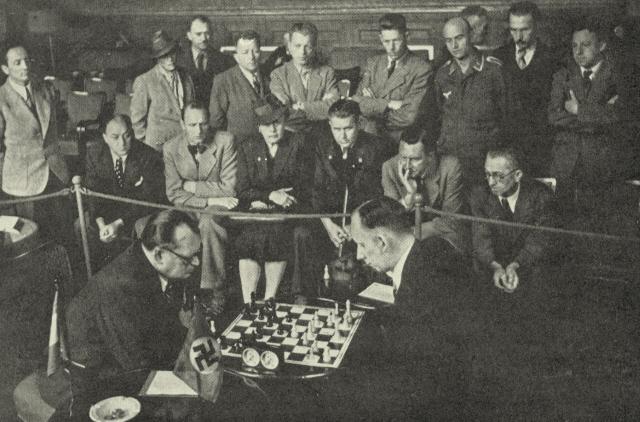

A. Alekhine v K. Richter, Munich, 1941. Source: page 71 of Alt om Skak by B. Nielsen (Odense, 1943)

A brief extract from C.N. 11864, concerning Fifty Shades of Ray by Raymond Keene (Edinburgh, 2021):

The scrappy sections on Alekhine and the Nazi articles are illogical and self-contradictory. Raymond Keene, the antithesis of a chess historian, seldom offers sources, preferring bare assertion as if he, of all people, can be taken on trust. Page 109 has categorical statements about how exactly Alekhine died (which nobody knows) and when he died (‘on the evening of March 25, 1946’). As shown in our feature article on the subject, Alekhine’s death had been reported worldwide the previous day.

Addition on 26 May 2021:

A detailed document on-line is Schachweltmeister und Günstling von Hans Frank? by Christian Rohrer. [Subsequent English version.]

Addition on 3 June 2021:

Following an enquiry in C.N. 5653, it was shown by John Townsend (Wokingham, England) in C.N. 11869 that official documents give the name of the organizer of London, 1946 as Walter Hatton Ward (as opposed to, for instance, W[illiam] Hatton-Ward). Consequently, in the present article and elsewhere we have replaced Hatton-Ward by Hatton Ward.

Addition on 18 March 2022:

Marcello Sibille (Uruguay) draws attention to the comments of Francisco Ojeda Cobos which were quoted by Ricardo Aguilera in his introduction to Gran Ajedrez (Madrid, 1947).

From Chess Thoughts:

A good historian knows when to be a waverer.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.