Edward Winter

Alexander Alekhine (1892-1946)

Contradictory accounts of Alekhine’s death are rife, and here we present the main evidence and miscellaneous related claims.

The reigning world champion was found dead in his hotel room in Estoril, Portugal on the morning of Sunday, 24 March 1946. Under the heading ‘Alone in a Foreign Land’, the March-April 1946 American Chess Bulletin (page 27) wrote:

‘According to reports sent out by international news agencies, Dr Alekhine was found in his room slumped over a chess board. Angina pectoris, aggravated by choking on a piece of meat, is said to have caused death. Burial did not take place until 16 April, funeral expenses being borne by the Chess Federation of Portugal.’

Page 7 of the April 1946 Chess Review reported:

‘On 24 March a radio newsflash announced the death of world champion Alexander Alekhine at the age of 53 in Lisbon [sic]. First reports ascribed his death to a heart ailment, but a subsequent autopsy disclosed that death had been caused by “asphyxia due to an obstruction in his breathing channels due to a piece of meat”.

This was amplified by an Association Press dispatch: “When Alekhine was found dead on Sunday in the Hotel Estoril [sic], he held a piece of beefsteak in his right hand. Intimates said Alekhine was accustomed to eating with his hands, never using knives or forks when he could avoid them, and that he would eat alone when he wanted complete enjoyment from a meal.”’

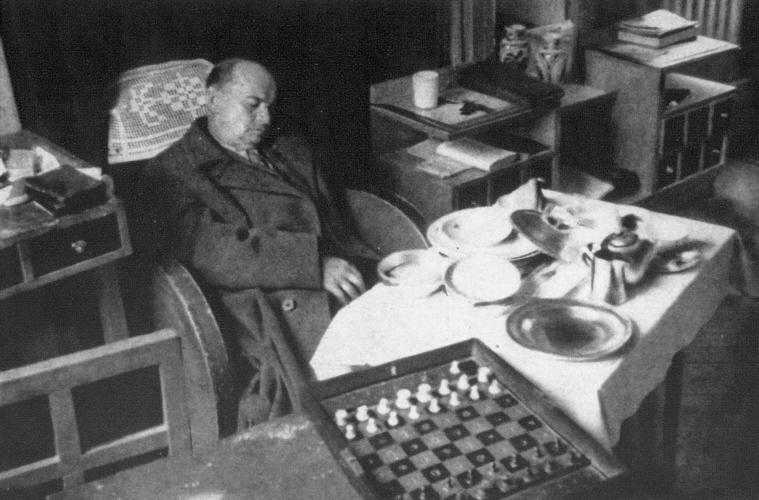

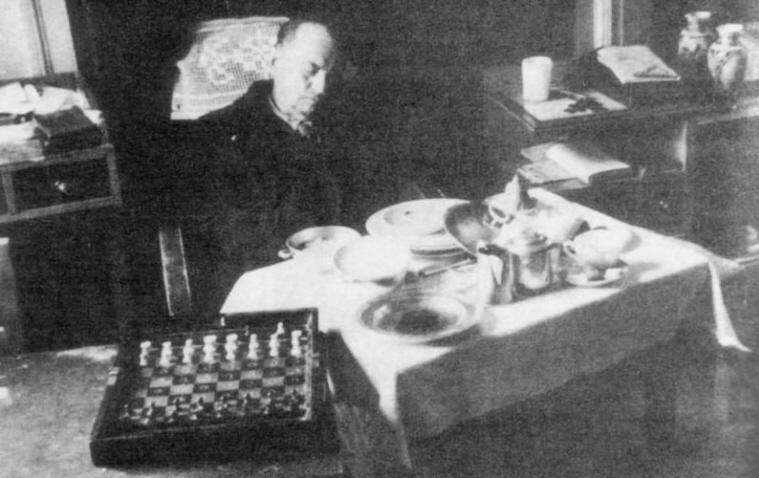

The May 1946 CHESS (page 167) stated, ‘Suicide was suspected but the official inquest verdict was heart failure’. The same page featured the famous photograph of Alekhine in his hotel room. (‘We reproduce the photograph with which the Sunday Pictorial scored a real “scoop” of Alekhine dead at his table with his chessboard beside him.’)

It emerged (as discussed below) that the photograph in CHESS was not the only one.

Elsewhere in the same issue (pages 171-172) CHESS commented:

‘All kinds of stupid statements have appeared in the press concerning Alekhine’s death. One of the most frequent reports is “he fed with his fingers and was choked by a lump of steak he had stuffed down his throat with his hands”. According to medical opinion, failure of the heart is frequently accompanied by a choking sensation which the victim attempts to remove by putting one or more fingers into the throat passage. If Alekhine had, as the popular press stated, been eating a piece of steak this, during the unconsciousness following heart failure, could have readily lodged in his wind-pipe while Alekhine’s fingers would automatically have sought for his throat for the reason given above.’

The unbecoming account of Alekhine’s table manners was immediately disputed by people who had eaten with Alekhine in past years. See, for instance, pages 1-2 of the 1 April 1946 Chess World, quoted on page 280 of A. Alekhine Agony of a Chess Genius by P. Morán.

All kinds of other claims about Alekhine made it into print. For example, the June 1946 CHESS (page 198) mentioned a report from the News Chronicle of 6 April 1946:

‘Dr Alekhine used to drink three and a half pints of brandy a day. This was revealed today by doctors who are now examining his brain.’

We have no reports on file from the Portuguese press, but on page 35 of their book Schachgenie Aljechin H. Müller and A. Pawelczak quoted from the newspaper O Século. This stated that on the evening of Saturday 23 March Alekhine’s meal was brought to his room and he asked not to be disturbed before 11 o’clock the following morning. At that time a chambermaid found his body.

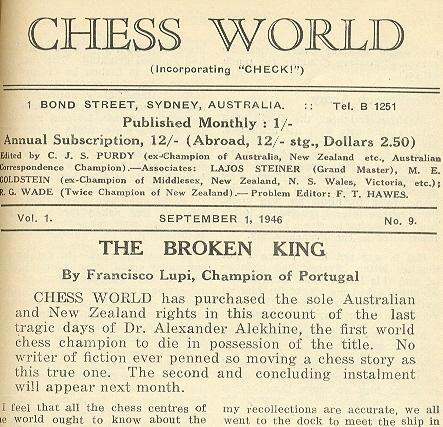

In his articles ‘The Broken King’ the Portuguese master Francisco Lupi gave a detailed account of his acquaintance with Alekhine. The following passage is taken from page 187 of Chess World, 1 October 1946:

‘The autopsy said of him that he suffered from arterio-sclerosis, chronic gastritis and duodenitis, that his heart weighed 350 grammes, that the perimeter of his skull was 540 millimeters, and so on …

All I know is that on Sunday morning about 10.30 I was awakened and asked to hurry to Estoril, because something had happened to “old Dr Alex”. I entered his room together with the Portuguese authorities. There he was, sitting in his chair, in so calm an attitude that one would have thought that he was asleep. There was only a little foam at the corner of his mouth.

The medical verdict as to the cause of death – that a piece of meat had caught in his throat – had no meaning for me.

To me he looked like the king of the chessmen, toppled over after the most dramatic game, the one played on the board of Life.’

Francisco Lupi

At the end of the article the Chess World editor (C.J.S. Purdy) added a brief note:

‘The verdict at the inquest on Dr Alekhine was heart failure, not choking. If a piece of meat caught in his throat, it must have happened as he lapsed into unconsciousness. He died in the company of his dearest friends: a peg-in travelling chess set lay open beside him.’

The above-mentioned book by Pablo Morán (page 278) gave a statement by Antonio J. Ferreira M.D.:

‘I was present at Alexander Alekhine’s autopsy, which took place in the Department of Legal Medicine, of the Medical School of the University of Lisbon. Alekhine had been found dead in his room in [an] Estoril hotel under conditions that were regarded as suspicious and indicated the need of an autopsy to ascertain the cause of death.

The autopsy revealed that Alekhine’s case of death [was] asphyxia due to a piece of meat, obviously part of a meal, which lodged itself in the larynx. There was no evidence whatsoever that foul play had taken place, neither suicide nor homicide. There were no other diseases to which his sudden and unexpected death could be attributed.’

See also, with all due caution, page 37 of With the Chess Masters by G. Koltanowski for a further passage by Dr Ferreira.

According to Morán’s book (page 281 of the English edition) at the time of his death Alekhine was analysing and annotating a game between A. Medina and A. Rico in the 1945 Spanish Championship in Bilbao. Even so, in the photograph of Alekhine’s body all the pieces were on their starting squares.

As regards Alekhine’s financial circumstances, Lupi wrote (Chess World, 1 October 1946, page 186):

‘Fifteen days before his death, I was called on the telephone and heard Dr Alekhine ask me sadly whether I wanted to work with him on “Comments on the Best Games of the Hastings Tournament”, adding, “I am completely out of money and I have to make some to buy my cigarettes”.’

Nonetheless, we note that the Müller and Pawelczak book on Alekhine (see the photograph caption opposite page 272) stated that he was staying at the Hotel Palace in Estoril, which we take to be the Hotel Palácio, i.e. an establishment of some standing.

We shall be grateful if any correspondents, not least in Portugal, can help us piece together more information on any aspects of Alekhine’s death.

The above account was presented in C.N. 3057, and we reverted to the subject in C.N. 3086. The full text is given below.

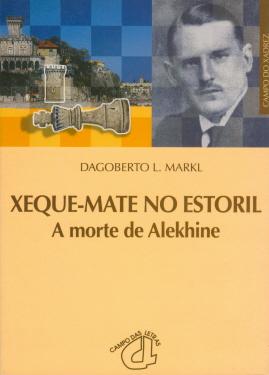

After

the

appearance of C.N. 3057 Luís Costa, the President of the

Portuguese Chess Federation, wrote to us about a book published in

September 2001 by Campo das Letras, Porto, Portugal, Xeque-Mate

no

Estoril by Dagoberto L. Markl. Having now procured a copy,

we revert to various points raised by our correspondent.

After

the

appearance of C.N. 3057 Luís Costa, the President of the

Portuguese Chess Federation, wrote to us about a book published in

September 2001 by Campo das Letras, Porto, Portugal, Xeque-Mate

no

Estoril by Dagoberto L. Markl. Having now procured a copy,

we revert to various points raised by our correspondent.

Firstly, Müller and Pawelczak’s book misidentified the hotel in which Alekhine died. Although he usually stayed at the Estoril Palácio Hotel (which still exists today and has an Alekhine Room), from 5 January 1946 onwards he was at another establishment in Estoril (demolished many years ago), the Hotel do Parque. Professor Markl’s book includes a photograph of the hotel registration form completed by Alekhine upon arrival, as well as a reproduction of his official death certificate, which specified the Hotel do Parque as the place of death.

Mr Costa comments:

‘This hotel question is intriguing. The Palácio was the German hotel during the War, whereas the Parque was the Allies’ hotel. Why did Alekhine, who was friendly with the Germans, stay at the Parque during his final visit? At that time the decision concerning where Alekhine stayed was taken by the political police.’

As regards the photographing of Alekhine’s corpse, Professor Markl’s book reproduces a letter written on 24 March 1946 by Luís C. Lupi to Robert Bunnelle of the Associated Press in London. In quoting it below we have corrected the spelling but not the syntax.

‘Dear Bunnelle,

Herewith please find four (4) negatives and three prints of EXCLUSIVE ASSOCIATED PRESS PHOTOS taken by me.

They are ALEXANDER ALEKHINE last photographs. I took these pixs with a small camera that I borrowed in the Hotel Park in Estoril where I rushed to cover the Alekhine death story – without my own camera! This is why they are not so good.

Pixs show ALEKHINE lying dead in his hotel room just as he was found in the morning of 24/3, by one hotel waiter. He must have died the night before (23/3) at about eleven p.m. as, according to the porter of the hotel, the Chess Champion went in about 23.40 – and had ordered his dinner to his room as usual. [Page 142 of the Portuguese book notes the timing discrepancy here, i.e. regarding 23.00 and 23.40.]

He seemed to be sleeping so calm and natural he looked. Doctors said he must have died suddenly just when he was beginning to eat. On his right hand he still held a beefsteak – He ate with his hands and used knife and fork only when he ate in public…

The giant of Chess – dead, resembled a fallen oak tree. In his face he kept an expression of deep thought.

For captions suggest you use (if you will use these gruesome pixs…) and rewrite my messages of 23/3 slugged 01230 and 02345. Will you have a couple of prints on these negatives (a couple of each, please)?

and oblige

Yours sincerely,

Luís C Lupi.’

The book reproduces two of the photographs of Alekhine, as given above. Our correspondent comments:

‘A careful comparison shows that some objects (papers near the vases) are absent from one of the shots. There are at least four photographs of Alekhine’s death. We have found only two in Portugal. As noted in Luís Lupi’s letter, the negatives were sent to the Associated Press in London, so it is only in their archives that it may be possible to find them.

The photographs were composed, as it is now an undisputed fact that the chessboard was placed there for the purposes of the shots. A few days after Alekhine’s death Francisco Lupi gave Rui Nascimento (a chess composition master and a strong chess player at that time; he is still alive) the better known “last” photograph of Alekhine. Francisco Lupi pointed to the chessboard and told Rui Nascimento that it had been put there by Luís, his stepfather, before he took the photographs.

Luís Lupi was connected with the PIDE (the political police of António Salazar’s dictatorship) and he was the Associated Press’ director in Portugal, appointed by the Government. He could do what he wanted with the “scene”.’

We do not feel at liberty to reproduce extensively the research presented in Xeque-Mate no Estoril, but a general description of the book’s contents may be useful. The most important part relates Alekhine’s visits to Portugal from 24 January 1940 onwards and supplies considerable documentary detail on the world champion’s last weeks and, in particular, the circumstances of his death. Along the way, the wildly inaccurate statements of writers such as Kotov and, especially, Bjelica, are criticized and mocked.

‘… Alekhine was receiving instruction preparatory to becoming a Catholic when he died suddenly at Estoril, states the Universe Lisbon correspondent.’

Source: CHESS, June 1946, page 198.

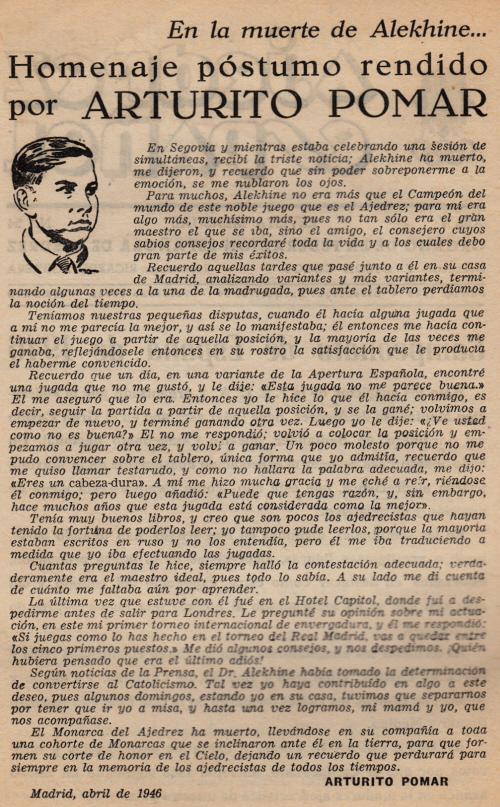

Writing in April 1946, Arturo Pomar, who was then aged 14, mused that he had perhaps helped the process, since Alekhine had even accompanied him to church. Here is the relevant passage from page 178 of Ajedrez español, June 1946:

‘Según noticias de la Prensa, el Dr Alekhine había tomado la determinación de convertirse al Catolicismo. Tal vez yo haya contribuido en algo a este deseo, pues algunos domingos, estando yo en su casa, tuvimos que separarnos por tener que ir yo a misa, y hasta una vez logramos, mi mamá y yo, que nos acompañase.’

The boy paid a warm tribute to Alekhine, describing him as a friend and adviser whose wise counsel he would never forget:

‘Para muchos, Alekhine no era más que el Campeón del mundo de este noble juego que es el ajedrez; para mí era algo más, muchísimo más, pues no tan sólo era el gran maestro el que se iba, sino el amigo, el consejero cuyos sabios consejos recordaré toda la vida y a los cuales debo gran parte de mis éxitos.’

(3116)

In the final paragraph of page 64 of World Chess Champions (Oxford, 1981) we wrote, ‘When Alekhine himself died it was discovered from his papers that he had been planning a collection of the Cuban’s best games.’ That gives a false impression, for we have now noted this reference to Alekhine on page 275 of the December 1944 BCM: ‘At present he is arranging publication of four of his books in Spain, and is planning a new one – his 18th book – on Capablanca ...’

(1423)

The March 1989 Revista Internacional de Ajedrez (pages 12-15) has an interview with the Spanish-born master Francisco José Pérez, a Cuban resident since the early 1960s. His reminiscences on Alekhine are of interest, and we give below a brief compendium of some of his replies to F.J. Ochoa de Echagüen:

‘He was, possibly, the greatest player of all time. I played four tournament games against him (3½-½ to Alekhine) and many friendly ones. ... He was not very good at fast chess. ... I spent a long time with him. He revised the manuscript of the book Ajedrez Hipermoderno which I wrote with Ricardo Aguilera. The book was a kind of bringing up to date of Réti, along the lines of Masters of the Chess Board. Those were six months of unforgettable collaboration with the master. He was staying at the Hotel Capitol, and two days a week he analyzed with me. Incidentally, I will mention that in general he spoke well of the majority of chessplayers, except Nimzowitsch, who he said was mad.

... During the Second World War Alekhine played in many European tournaments. In 1943, when he arrived in Spain, Hitler held his wife in France (she was French [sic]) to ensure that he would return. Alekhine’s separation from his wife had a decisive effect on him. While playing in a tournament in Sabadell in 1945, Alekhine said that he did not have the courage to commit suicide, for his wife had written to him saying that she did not want to hear from him any more. This was largely because of his fondness for alcohol. Shortly afterwards, he was invited to play in the important London tournament. In Madrid some time later I met Alekhine ... It was the last time I was to see the remarkable champion alive. He showed me the telegram which cancelled his invitation to London because of, he claimed, threats by Euwe and Fine that they would not take part if he went; they accused him of collaborating with the Nazis by means of supposed anti-Semitic articles which he always denied having written. All this had an enormous effect on him and probably hastened his death, which occurred a few months later.’

(1854)

The October 1988 issue of the South African magazine Chess in the RSA (pages 9-12) has a light interview with Frank Korostenski (born 1949). One question, ‘Have you ever met any great players?’, received this reply:

‘Let me think ... in a way, nearly. When I was in Estoril, Portugal, I sought out the grave of Alexander Alekhine. It was a hot afternoon the day of my intended visit, and I was unaccountably delayed in a bar near the bus station, where I was sampling some Bagazeiro – which is something like cane. Realizing that the cemetery might be closing, I rushed out and grabbed a taxi. But I was too late. In reply to my enquiry, the so-called “guardian of the graveyard” confirmed that a chessplayer of some stature was buried there, but no financial inducement would allow me access to his grave.’

Mr Korostenski was indeed ‘too late’. Alekhine’s remains had been removed to the Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris, in the mid-1950s.

(1820)

Below is the report by ‘J.A.S.’ (Jakob Adolf Seitz) on page 220 of CHESS, 28 April 1956:

‘In memory of the tenth anniversary of the death of the late world champion Alexander Alekhine, several hundred people – more than one would have expected on an icy cold day – gathered outside the main entrance to Paris’s famous Montparnasse cemetery, just before eleven in the morning of 25 March 1956.

Folke Rogard, President of the International Chess Federation, was one of the first to arrive. Soon there came a strong delegation from the USSR led by grandmaster Ragozin. Some unkind tongues suggested that the Russian chessplayers were the main attraction of the ceremony to many locals; and certainly Smyslov, Keres, Bronstein, Geller, Petrosian and others were energetically pestered for autographs.

At 11 a.m., which was said to have been the hour of Alekhine’s death, the crowd moved to the monument.

We found that Abraham Baratz, a gifted sculptor, many times chess champion of Paris in his younger days, had chiselled a statue of Alekhine in his youth sitting at a chess board. All in white marble; and it was to be noted that his chessmen were not Staunton, but French, in type.

The base of the tumulus was a huge chessboard itself, though few noticed it at the time, so completely was it covered by wreaths, of which the Soviet delegation’s was the biggest. Beneath the sculpture appeared first Alekhine’s name in his native Russian characters, then the inscription “Alexandre Alekhine, génie des échecs de Russie et de France, 1 novembre 1891 – 25 mars 1946” and below “Grace Alekhine née Wishar 1876-1956”.

On the socle of the tumulus was an announcement that the monument had been erected on 25 March 1956 by the International Chess Federation. The names of Rogard (Sweden), Ragozin, Berman (France), Botvinnik (who was not present), Count dal Verme (Italy) and others followed.

Among French chessplayers present were Dr Bernstein, C. Boutteville (present French champion), Biscay, Halberstadt, Mme Chaudé de Silans, Muffang, Ségal and others. Edmond Lancel had come from Brussels. Rogard gave a brief address in French, Ragozin another in officially translated Russian. Alekhine’s son responded, followed by Mme Isnard, a daughter of Alekhine’s last wife. The chessplayers then repaired to a famous restaurant, where a hundred anecdotes about Alekhine were exchanged. Not one word about this impressive ceremony did I find in any of the French newspapers – a sad commentary on the place of chess in France today.’

Confusion with the dates may be noted. Firstly, the date on the tombstone was ‘1 November 1892’, not 1891 (although the correct date of Alekhine’s birth is 31 October 1892). The ‘1891’ was apparently Seitz’s error and not a misprint by CHESS, because it also occurred in a similar report by Seitz on page 83 of the April 1956 Schweizerische Schachzeitung. The latter magazine, moreover, quoted Alekhine’s death-date on the tombstone as ‘25 March 1956’, instead of 25 March 1946, although the latter too was wrong. As chronicled in C.N. 3086, Alekhine was found dead in the Hotel do Parque, Estoril on the morning of 24 March 1946.

(4043)

From page 115 of CHESS, March 1946:

‘Botvinnik has written Mr Derbyshire, President of the British Chess Federation, saying that the Moscow Chess Club is willing to sponsor a world championship match Botvinnik v Alekhine and put up 10,000 dollars (£2,500). Two-thirds to go to the winner and the balance to be allocated to expenses. The BCF to organize the entire match. Mr Derbyshire is planning to commence the match during the tournament at Nottingham in August.’

From page 143 of CHESS, April 1946:

‘Alekhine has accepted Botvinnik’s challenge to a world championship match, subject to the conditions being the same as those under which he was negotiating to play Botvinnik in 1939. The British Chess Federation will be asked at its Executive meeting on 26 March whether it is willing to accept responsibility for organizing the event.’

From page 168 of CHESS, May 1946:

‘After considerable discussion, the BCF agreed to organize the Alekhine-Botvinnik match, but only because no effective International Chess Federation was in effective existence and only on condition that both players should bind themselves to submit to the ruling of such a Federation in connection with the next following match.

(Next day, Alekhine’s death was announced.)’

João Pedro S. Mendonça Correia (Lisbon) reverts to the circumstances of Alekhine’s death. We have mentioned that Xeque-Mate no Estoril by Dagoberto L. Markl (Porto, 2001) reproduced, opposite page 113, Alekhine’s death certificate (Registo de Óbito). Dated 27 March 1946, the document gave as the cause of death ‘Asfixia por obstrução dos vasos aéreos superiores produzido por pedaço de carne’ (Asphyxia resulting from obstruction of the upper air passages produced by a piece of meat).

The death certificate was signed by Dr Asdrúbal d’Aguiar, on whom our correspondent provides some information:

‘Born in Lisbon on 15 August 1883, Asdrúbal António d’Aguiar was Portugal’s leading expert on forensic pathology. He died in Lisbon on 28 November 1961. Further information is available at a webpage of the Academia das Ciências de Lisboa.

Asdrúbal António d’Aguiar

The writings of Dr Asdrúbal d’Aguiar included an excellent three-volume treatise on forensic pathology (over 1,500 pages), published in Lisbon during the Second World War. The first volume is about forensic traumatology and has a learned, lengthy treatment of suffocation from page 459 onwards.

Despite the highly technical character of that treatment, my own reading of the chapter (about 20 pages), in conjunction with the photographs of Alekhine taken after his death, is that he could not, in fact, have died as a result of a piece of meat becoming stuck in his throat.’

Below is the back-cover of Xeque-Mate no Estoril:

Dr Mendonça Correia informs us that Dagoberto L. Markl died in Lisbon on 4 April 2010.

(6794)

Addition on 11 August 2013: Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, Canada) draws attention to a photograph which shows that the Hotel do Parque and the Palácio Hotel stood side by side.

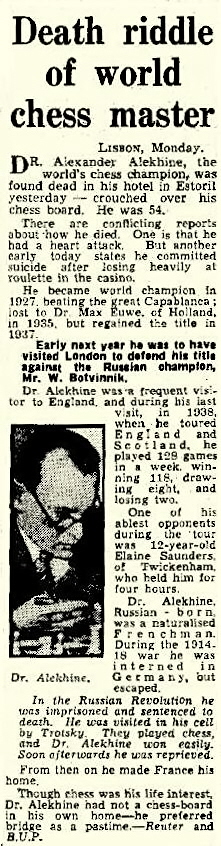

Alekhine’s death was reported on the front page of the Daily Mail, 25 March 1946, with a seamless blend of rumour and error:

(8258)

Shortly after Alekhine’s death, Arturo Pomar published a tribute which included some comments on his personal contact with the late world champion:

Source: Ajedrez Español, June 1946, page 178.

(8750)

Page 7 of Alekhine move by move by Steve Giddins (London, 2016) has Mr Giddins’ contribution on the topic of Alekhine’s death:

‘And even his death has been questioned, with suggestions he may have been murdered by a Soviet hitman. Admittedly, this latter theory has much less substance, and should probably be grouped with those that suggest the moon landings were faked and that Princess Diana was murdered by Lord Lucan, with Elvis Presley (or was it Dick Cheney?) driving the getaway car.’

(9888)

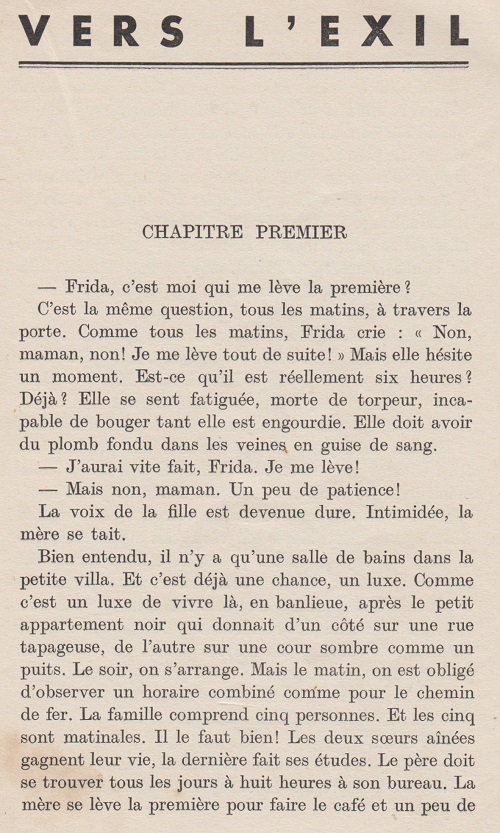

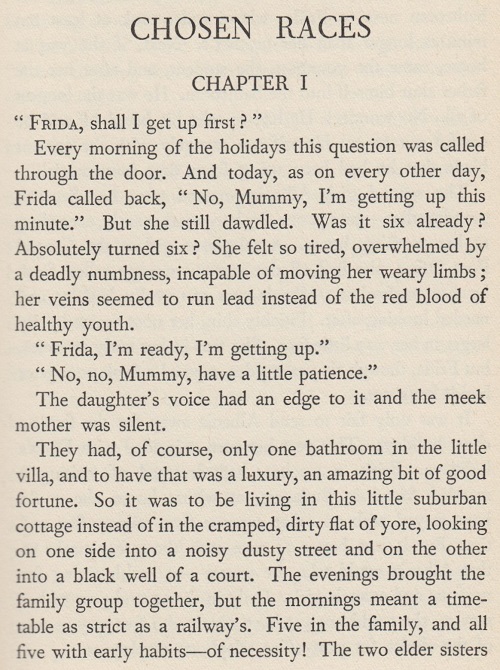

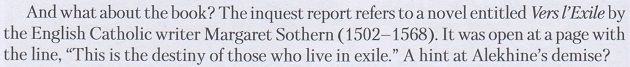

A copy of Vers L’Exil by Margareth Sothern (Paris, 1939), translated by Juliette Bertrand, was allegedly found beside Alekhine’s body in Estoril in 1946, and a number of C.N. items have discussed the book and its English edition, Chosen Races (New York, 1939). In the latter volume, a translation by Maisie Ward, the author’s forename was spelled ‘Margaret’.

The first page of each edition:

Bizarrely, the novelist has been labelled a sixteenth-century figure. From page 206 of Alekhine’s Odessa Secrets: Chess, War and Revolution by Sergei Tkachenko (Moscow, 2018):

The relevant passage on page 244 of the original Russian edition, Odesskie tayny Aleksandra Alekhina (Moscow, 2016/17):

Another random example of Tkachenko’s approach to scholarship, from page 207:

In the Russian original the passage is on page 245.

Page 109 of Das Spiel der Könige by Alfred Diel (Bamberg, 1983) stated that Alekhine died in Lisbon on 25 March 1944.

At least one chess writer has even affirmed that Alekhine retained the world championship after his death. On page 34 of Chess Openings for Progressive Players (London, 1949) M. Graham Brash intentionally gave the dates of the second reign as 1937-1948 ‘although Dr Alekhine died in 1946’.

(2407)

Roberto Roig (Lima) draws attention to a report on page 29 of ABC, 26 March 1946.

A brief extract from C.N. 11864, concerning Fifty Shades of Ray by Raymond Keene (Edinburgh, 2021):

The scrappy sections on Alekhine and the Nazi articles are illogical and self-contradictory. Raymond Keene, the antithesis of a chess historian, seldom offers sources, preferring bare assertion as if he, of all people, can be taken on trust. Page 109 has categorical statements about how exactly Alekhine died (which nobody knows) and when he died (‘on the evening of March 25, 1946’). As shown in our feature article on the subject, Alekhine’s death had been reported worldwide the previous day.

See also the references to Margareth/Margaret Sothern in the Factfinder.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.