Edward Winter

A familiar blindfold brilliancy:

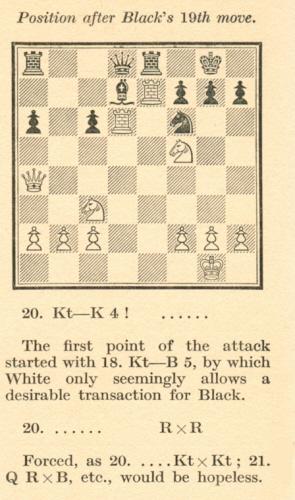

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Bxc6 bxc6 5 d4 exd4 6 Qxd4 d6 7 O-O Be6 8 Nc3 Nf6 9 Bg5 Be7 10 Qa4 Bd7 11 Rad1 O-O 12 e5 Ne8 13 Bxe7 Qxe7 14 exd6 cxd6 15 Rfe1 Qd8 16 Nd4 Qc7 17 Re7 Nf6 18 Nf5 Qd8 19 Rxd6 Re8

20 Ne4 Rxe7 21 Nxf6+ Kh8 22 Nxe7 Qxe7 23 Qe4 Qxe4 24 Nxe4 Be6 25 b3 g6 26 Nc5 Bf5 27 Rxc6 Re8 28 f3 Re2 29 Rxa6 Rxc2 30 Ne4 Be6 31 h4 Kg7 32 Kh2 Kh6 33 Kg3 Bd7 34 a4 f5 35 Ng5 Rc3 36 Ra7 Rd3 37 a5 Kh5 38 Nxh7 Resigns.

This game (Alekhine v Kimura, Tokyo, 20 January 1933) appeared in the world champion’s second Best Games volume, and the circumstances were discussed at length on pages 442-443 of the Alekhine book by L. Skinner and R. Verhoeven. The co-authors noted that although the game was widely published at the time, with Kimura listed as one of the opponents in Alekhine’s exhibition, suspicions had been expressed as to the game’s authenticity. They mentioned the following letter from John Kalish on page 273 of the July 1968 Chess Life:

Richard Sams (Tokyo) informs us that an article by Yoshio Kimura entitled ‘Thoughts on Chess’ was published on pages 190-193 of the magazine Bungei Shunju, April 1933. Below is the complete text, in our correspondent’s translation from the Japanese:

‘About a decade has passed since I first took an interest in Western shogi (chess) and decided that I would like to study it. At that time, there was a chess club at the back of the Imperial Hotel and there I first learned how to play chess under the tutelage of an Englishman, Mr Havilland, who was apparently once an amateur chess champion. At first I learned only the basics, and for a while I had no opponents or opportunities to play. Fortunately, however, through the support and guidance of Dr Ishida of the Riken Group and Professor Mitamura of the Imperial University of Tokyo, I was able to acquire useful knowledge of chess openings and strategies. Upon inquiring about the most notable chess matches, I was surprised to learn the extent to which chess has gained international popularity as the ultimate intellectual contest. This aroused my interest further, giving me an even greater desire to study the game more deeply.

From that time on, Professor Mitamura helped me with my studies by providing me not only with well-known books on chess but also with specialist publications on matches from Europe and America. I thereby acquired a little knowledge of the exploits of leading players in the West and the most recent matches taking place around the world. This greatly increased my enthusiasm, and I even came to embrace the conceit and ambition that, if I could make a serious study of chess as I had of shogi, I might even be able to compete for the world championship.

One reason I came to think this is that, because chess is quite similar to shogi in many respects from strategy to the deployment of pieces and tactical methods, I would be able to adapt to its fundamental reasoning. Furthermore, the fact that, unlike in shogi, the pieces are no longer in play once they have been captured made chess seem quite simple (from the viewpoint of a professional shogi player). Therefore, armed with the profound technical skills characteristic of shogi, I might even be able to compete for the world championship in chess. Until quite recently, I had confidently held this conviction.

Seven years ago, the Tokyo Chess Club was established with the late Dr Fukada as President and Dr Masataka Ota as Vice-President. The inaugural meeting took place at the Tokyo Kaikan. Subsequent club meetings were held twice a month in a room in the Imperial Hotel. The original founding members were Dr Fukada, Viscount Masatoshi Okouchi, Dr Ota, Count Akira Watanabe, Baron Tatsukichi Nagakoshi, Mr Jozo Ikoma, Dr Yoshio Ishida, Dr Masaharu Nishikawa and Professor Atsushiro Mitamura, together with the professional shogi players Osaki 8-dan, Kon 8-dan and me.

The club met twice a month and, with the attendance of four or five chess enthusiasts from overseas, it flourished for a while. It was very enjoyable to do battle with foreigners over the chess board, but after Dr Ishida, Professor Mitamura and I decisively defeated three foreign opponents, including the strong player Mr Havilland, we found ourselves without any suitable rivals and had no choice but to play each other. As a result, the club’s activities gradually fell into abeyance.

At the time, I was quite intoxicated with feelings of superiority, having beaten foreigners at chess, but I was also concerned because I did not really know my true strength (in the eyes of a professional chessplayer). Then I learned that the world chess champion Alekhine, who was en route to a match in Shanghai, was planning to visit Japan on 16 January for just one week. I had already heard of Mr Alekhine about seven or eight years previously and viewed this as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to determine my chess ability. Professor Mitamura telephoned Mr Alekhine to arrange a meeting, and we went to his hotel the following day (17 January). Somehow we missed him at the hotel and had to wait for a while. As usual, Professor Mitamura was well prepared. He showed me a photograph of Mr Alekhine at the front of a book which the world champion had written on a recent international tournament, so that we could stop him if we saw him leaving the hotel. Shortly afterwards Mr Alekhine appeared, and I was introduced to him as a professional shogi player. He is a splendid-looking gentleman, well built and easily six feet tall. He was more approachable than I imagined and seemed to possess a strong artistic sensibility. When Professor Mitamura showed me Mr Alekhine’s book, explaining how rich it was in content as a practical guide for students of chess, Mr Alekhine’s face seemed to light up, and he at once became more relaxed and familiar. He said he had heard that different forms of chess were played in Japan, China and India, and that, since Japanese chess was particularly sophisticated, it should be studied. He had therefore decided to come to Japan to learn more about it. As professional shogi players, we had considered the possibility of promoting shogi overseas, but we thought that it might be hard to understand for Westerners, who find chess a sufficiently difficult game. We also could not think of any suitable way of explaining the excellence of shogi and teaching it. However, considering that the most effective method would be for a respected professional chessplayer such as Mr Alekhine to introduce shogi to the world, I decided to take it upon myself to teach him the game.

Through the good offices of Dr Ishida we then made arrangements for a gathering of Japanese and foreign chess enthusiasts to honor the world champion. The Japan Shogi Federation undertook to organize a party and provided various assistance in making the preparations. We were particularly grateful to Count Yanagisawa for his help and to Mayor Nagata, who went so far as to arrange a welcome reception at the Japan Club, where Mr Alekhine was presented with a souvenir.

When the preparations had been made, what we desired most of all was for Mr Alekhine to display his skills as the world chess champion. He agreed to this, proposing to play a blindfold simultaneous display against all of us. I thought that, even for the world champion, it would be difficult to play simultaneously against 14 opponents of different strengths, to keep the positions in his mind and remember the moves of all the games without making any oversights, and surely impossible to win all of them, whatever the difference in strength between him and his opponents. However, Professor Mitamura pointed out that, since Mr Alekhine was the world record holder in blindfold simultaneous chess and had played blindfold against 26 opponents in New York in 1926 and 28 opponents in Paris in 1928, he should have no difficulty with just 14 opponents.

Here I think a brief outline of how Mr Alekhine has succeeded in reaching the pinnacle of world chess will provide insights into his serious attitude to chess and his character, which has particularly impressed me. Mr Alekhine is currently a French citizen living in Paris, and plays mainly against Russian opponents. A Polish-Russian, he is 42 years old according to the Japanese age-counting system. In 1914, while he was taking part in an international tournament in Mannheim, Germany, the Great European War broke out and he was for some reason taken prisoner. After being interned for almost two months, he was released and returned to Russia. He was drafted into the army and fought bravely, but having earlier graduated from law school, he was soon appointed to serve in the foreign ministry, mainly undertaking work related to criminal law. After he left this post, the Russian Revolution occurred and, under the suspicion of the Soviet Government, he was again imprisoned for a while, but succeeded in escaping to Paris five years later. Clearly he experienced great vicissitudes of fortune up to the time he became a French citizen in 1921. In 1924, he displayed his strength at the New York international chess tournament, where he came third below Lasker and Capablanca, who took first and second places respectively. In the spring of 1927, he again took part in an international tournament in New York, coming second behind the world champion Capablanca, thereby obtaining the right to challenge the latter to a match. This took place in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in the autumn of 1927. After a two-month long battle, Alekhine won an overwhelming victory of 6-3 and was crowned world champion. In 1931, he was challenged by Bogoljubow, another Russian who had become a German citizen, brilliantly retaining his world championship title with a score of 6-3. [It will be noted that Kimura’s biographical information about Alekhine contains a number of factual errors.]

Alekhine’s record since winning the world championship has been outstanding. He has not just won first prize in tournaments all over the world but has also won his games in fine style. His attitude to chess is deeply serious and he shows no sign at all of underestimating his opponent. Although I am considered a strong chessplayer in Japan, I must seem to him a mere novice. Nevertheless, when he sat down to play me, he showed no sign of relaxing his attention, and at moments where an unexpectedly interesting position arose he studied the position afterwards and explained it with the attitude of a researcher. His kindness and obvious passion for the game made this encounter a very pleasant experience for me.

Alexander Alekhine

According to Professor Mitamura, the world champion is well liked all over the world and praised for his character considerably more than other leading chessplayers. This reputation speaks volumes about his nature and breeding. Mr Alekhine says that for him chess is a way of refining the intellect and should transcend materialism, a statement which reflects his spiritual nature. He gives the impression of being very sensitive and straightforward, with no interest in flattery or deferring to conventional wisdom. I think that this is because, as well as being courteous and modest, he is above all an artist. His attitude calls to mind the Western tradition of chivalry, which is similar to the spirit of Bushido in Japan.

We did not have much time to teach shogi to Mr Alekhine but succeeded in outlining the rules, how the pieces move, and some basic opening strategies. He is a very quick learner. When I played a game with Professor Mitamura to show him an example of actual play, he indicated a move which he had not expected and asked about the best move in that position. This no doubt comes from his knowledge of chess, which gives him a confidence one rarely sees in people when they first learn shogi. I am sure that he will be able to introduce the game in the West based on what he has learned, and that this will make a great contribution to the future development of shogi.

Representing the Japan Shogi Federation at the welcome party on 20 January at the Imperial Hotel were the Meijin (shogi champion) Sekine, Doi 8-dan, Kon 8-dan, Hanada 8-dan, and Mr Nakajima. The party was also attended by chess lovers from both Japan and overseas who wanted to witness the amazing feat which the world champion was about to perform, and this made for a very congenial and pleasant atmosphere. On behalf of the Japan Shogi Federation, Mr Nakajima made a welcome speech in fluent English, stating that shogi and chess came from the same roots and expressing the hope that we could cooperate for their mutual development. Mr Alekhine said that, while chess and shogi may constitute only a small part of our respective cultures, they can play a significant role in promoting friendship among the peoples of the world. He promised to introduce shogi in the West with this aim in mind.

Now it was time for the final event in the program, the blindfold simultaneous chess display. In addition to Dr Ishida and Professor Mitamura, Kon 8-dan and I participated as professional shogi players studying chess. Also taking part were the foreign chess enthusiasts Clausnitze, Alexander, Mosler, Baumfeld, Kramer and Gotzscheke.

All the games in the blindfold display were played without odds. Thinking that I would have no chance of winning if I activated my pieces too early in the opening, I adopted a strategy of defending and waiting for my opponent to make a mistake. In the end, all 14 of us lost without much of a struggle. Considering my initial hopes, I felt quite ashamed of my inability to put up serious resistance, but I was also deeply impressed by the world champion’s extraordinary display of chess skill. On the way home, Kon 8-dan said that he considered Mr Alekhine’s feat almost inhuman.

Mr Alekhine told Professor Mitamura later that, in view of my experience in shogi, I could become a strong chessplayer if I studied intensively for six months. He says that he would like to visit Japan again next year, so it seems that he also has desires to study shogi. I showed him all the hospitality I could during the remainder of his stay in Tokyo until his departure for Shanghai on the morning of 22 January.

Finally, I should also like to express my thanks to the foreigners who took part in the simultaneous display and all those who attended the event.’

From page 276 of My Best Games of Chess 1924-1937 by A. Alekhine (London, 1939)

On the analytical front, we made a brief comment about Alekhine v Kimura on page 317 of the July 1985 BCM, pointing out that in Chess Life, January pages 22-23, Jan Frise of Sweden had shown that Alekhine’s note to 20...Rxe7 was faulty, because after 20...Nxe4 21 Rdxd7 ...

... Black can play 21...Qxd7, with the continuation 22 Rxd7 Nc3 (threatening 23...Re1 mate and forcing White to take perpetual check with 23 Nh6+).

Frise’s discovery (we are aware of no reference to 21...Qxd7 before 1980) was overlooked on page 80 of Alekhine in Europe and Asia by J. Donaldson, N. Minev and Y. Seirawan (Seattle, 1993), which misascribed the line to G.B. Lewis (who had mentioned it much later than Frise, i.e. in 1985). For further remarks on the Alekhine v Kimura position, by Larry Evans, see Chess Life, March 1989 (page 58) and February 2002 (page 32).

On page 361 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves (an item reproduced in The Games of Alekhine) we observed regarding Alexander Alekhine’s Best Games by A. Alekhine (London, 1996):

‘Many analytical emendations pointed out over the years by third parties are ignored; for instance, Alekhine’s note to Black’s 20th move in his game against Kimura at Tokyo, 1933 has been widely censured, but the Batsford book offers no comment.’

Incidentally, it would appear that Alekhine made a small factual error in his Best Games book, giving the number of opponents in the blindfold display as 15, instead of 14.

Another master who visited Japan in the 1930s was Lajos Steiner. His report, ‘A Chessplayer Turns Explorer’ on page 37-38 of the February 1937 Chess Review, included this paragraph:

‘Among the Japanese themselves, there are, as far as I know, only two players with real insight into the game. One is Professor Mitamura, a great pathologist and a member of the Imperial University of Tokyo. He is a man of keen intelligence, who speaks English and German well. Kimura, the greatest living shogi player, is the other.’

An article on shogi by Larry Kaufman on pages 28-33 of the September 1983 Chess Life mentioned Kimura Yoshio and gave a photograph of Korchnoi receiving an explanation of shogi from Aono Teruichi in London in 1980.

(6994)

From Stephen Wright (Vancouver, Canada):

‘Your feature article on Alekhine v Kimura mentions the English player Mr Havilland. I do not think that it has been widely realized that this was Walter de Havilland, the father of the film stars Olivia de Havilland and Joan Fontaine. In later life his home was in British Columbia.’

On his British Columbia Chess History website our correspondent has written an article about Walter Augustus de Havilland (1872-1968).

(12147)

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.