Edward Winter

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 g3 Bg7 4 Bg2 O-O 5 Nc3 d6 6 Nf3 Nc6 7 d5 Na5 8 Qd3 b6 9 Nd4 Nb7 10 Nc6 Qd7 11 O-O a5 12 b3 Nc5 13 Qc2 Bb7 14 h3 Rae8 15 a3 Bxc6 16 dxc6 Qc8 17 b4 axb4 18 axb4 Na6 19 Ra4 Nb8 20 b5 h6 21 Ra7 e5 22 Kh2 Kh7 23 f4 Re7 24 fxe5 Rxe5 25 Bf4 Ree8 26 Nd5 Nxd5 27 Bxd5 Qd8 28 h4 Qe7 29 e3 Kh8 30 Kg2 f5 31 Re1 Kh7 32 e4 Be5 33 exf5 gxf5

34 c5 bxc5 35 b6 Rc8 36 Qc3 Rfe8 37 Bxe5 dxe5 38 Qxe5 Qxe5 39 Rxe5 Rxe5 40 Rxc7+ Rxc7 41 bxc7 Re8 42 cxb8(Q) Rxb8 43 Be6 Kg6 44 c7 Rf8 45 c8(Q) Rxc8 46 Bxc8 c4 47 Ba6 c3 48 Bd3 Kf6 49 Kf3 Ke5 50 Ke3 h5 51 Bc2 Kf6 52 Kf4 Kg7 53 Kxf5 Kh6 54 Kf4 Resigns.

**

On pages 273-275 of The Golden Dozen (Oxford, 1976) Irving Chernev gave the famous blindfold game between Alekhine and N. Schwartz, London, 1926, introduced as follows:

‘The highlight of this remarkable game, one of 15 played blindfold simultaneously, is a scintillating combination wherein Alekhine sacrifices a rook in order to queen two pawns – both of which are immediately captured.

It’s all part of the plot, though, in this impressive ending, which Alekhine himself considered one of his best achievements in blindfold chess.

The pleasing, graceful blending of profound strategy and lively tactics moves me to nominate it to occupy the niche reserved for The Immortal Blindfold Game in Caissa’s Hall of Fame.’

Chernev was mistaken in his reference to ‘one of 15 played blindfold simultaneously’. From page 79 of Blindfold Chess by Eliot Hearst and John Knott (Jefferson, 2009):

‘While in London in 1926 Alekhine played what he considered one of his “best achievements in blindfold chess”, against N. Schwartz ... He even included the game in published collections of his most memorable games [his second volume of Best Games and Auf dem Wege zur Weltmeisterschaft]. However, this game was not part of a regular simultaneous display, but was one of two blindfold games he played while meeting 26 other opponents face to face – a point not made clear in his books. Obviously, it is easier to play only two blindfold games at the same time as playing 26 other games with sight of the board, compared with playing all 28 blindfolded.’

The headings in the two above-mentioned books by Alekhine were ‘Blindfold exhibition in London, January 1926’ and ‘Aus einem Blind-Simultanspiel in London am 15. Januar 1926’. The notes in both books were essentially the same as those contributed by Alekhine on pages 314-316 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, April-June 1926, where the heading was ‘Gespielt in London am 15.1.26. Weiß: Dr Aljechin (ohne Ansicht des Brettes). Schwarz: N. Schwartz’. When a translation of the notes was published on pages 179-180 of La Stratégie, August 1926 the heading was longer: ‘Jouée le 15 janvier 1926 à Londres (Gambit Chess Rooms), sans voir avec une autre, ainsi que vingt-huit [sic] parties simultanées.’

Neither the BCM nor the Chess Amateur gave the game-score in 1926, although page 164 of the March 1926 Chess Amateur published another blindfold game between Alekhine and Schwartz played 11 days later (game 930 in the Skinner/Verhoeven book on Alekhine). Page 124 of the March 1926 BCM had a brief description of the display at which the ‘Immortal Blindfold Game’ was played:

‘On the following Friday he [Alekhine] was guest of Miss Price at the Gambit Chess Rooms, Budge Row, London; and here again 28 games (two sans voir) were played, the opposition being on the strong side. The blindfold games (N. Schwarz and J.H. Kahn) were beautifully won, but two players (C.A.S. Damante [sic – Damant] and E.T. Bazell) scored wins against the master, while others secured draws.’

The spelling ‘N. Schwarz’ apppears to be an error, since other issues of the BCM referred to ‘N. Schwartz’. Is it possible to find his full name?

(8564)

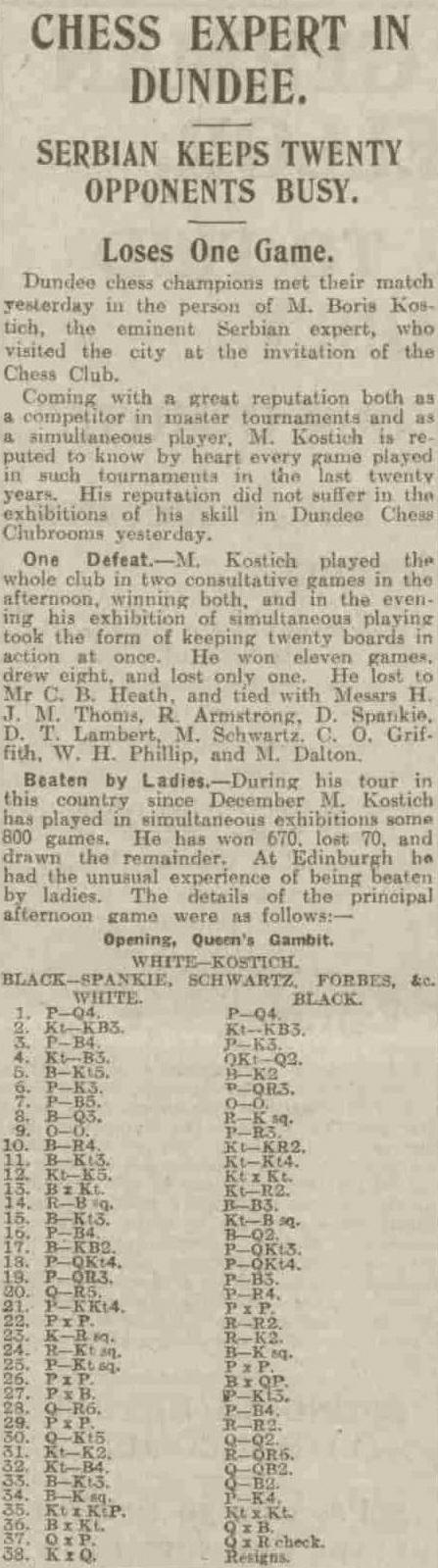

In the early 1920s the name N. Schwartz often appeared in connection with chess in Scotland. For instance, in 1922 he was one of seven participants in the Scottish championship in Perth (BCM, May 1922, pages 195-196), and other issues of the magazine (e.g. January 1922, page 22) referred to him as playing for Dundee. He was also mentioned on page 228 of the May 1922 Chess Amateur:

‘At Dundee Kostić played two consultation games, and won both, against Messrs. Heath, Thoms and Griffiths [sic – Griffith] at one board, and against Messrs. Spankie, Forbes, Schwartz, “etc.” at the other.’

The game involving Schwartz was published on page 6 of the Dundee Courier, 29 March 1922:

Boris Kostić – D. Spankie, N. Schwartz, C.S. Forbes and

others

Dundee, 28 March 1922

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 Nbd7 5 Bg5 Be7 6 e3 a6 7 c5 O-O 8 Bd3 Re8 9 O-O h6 10 Bh4 Nh7 11 Bg3 Ng5 12 Ne5 Nxe5 13 Bxe5 Nh7 14 Rc1 Bf6 15 Bg3 Nf8 16 f4 Bd7 17 Bf2 b6 18 b4 b5 19 a3 c6 20 Qh5 a5 21 g4 axb4 22 axb4 Ra7 23 Kh1 Re7

24 Rg1 Be8 25 g5 hxg5 26 fxg5 Bxd4 27 exd4 g6 28 Qh6 f5 29 gxf6 Rh7 30 Qg5 Qd7 31 Ne2 Ra3 32 Nf4 Qc7 33 Bg3 Qf7 34 Be1 e5 35 Nxg6 Nxg6 36 Bxg6 Qxg6 37 Qxe5 Qxg1+ 38 Kxg1 Resigns.

The newspaper’s chess coverage at that time had many references to ‘N. Schwartz’, and the initial ‘M.’ above would appear to be an error. Although the crosstable for the Scottish championship on page 196 of the May 1922 BCM also had ‘M. Schwartz’, the Scottish newspaper reports on the event that we have seen (e.g. the Dundee Courier, 19 April 1922, page 6) specify that the player was N. Schwartz. In no newspaper has his forename been found.

(8567)

From Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada):

‘There are several references to “N. Schwartz” in The Story of Dundee Chess Club by Peter W. Walsh (Dundee, 1984). The spelling is invariably “Schwartz”.

The ScotlandsPeople website includes the Valuation Roll for 1920-21, page 98, County of Perth, Parish of Longforgan. For one of the houses on Errol Road, Invergowrie, Nicolai Schwartz (“Russian correspondent”) is mentioned as the occupier. There is also a record of his marriage on 19 February 1916, at St Stephen’s Church, Broughty Ferry, District of St Andrew in the Burgh of Dundee. He was listed as Nicolai Schwartz, Commercial Correspondent (Bachelor), aged 22, of Leabank, Broughty Ferry. The bride’s name is not completely clear, but it looks like J. Vernon Le Cocq (the maiden name of her mother is shown as Vernon), aged 24, of Craigiebarn Road, Dundee. A son, Nicholas Roy Schwartz, was born in 1920 in the Parish of Longforgan, in Perth County (377/00 0037).

A Dundee city website has a Roll of Honour for those who died in the Second World War and provides details of the son’s death in action on 17 December 1944, aged 23. His name was given as Nicolai Roy Schwartz, and his next of kin were Nicolai and Jeannie V. Schwartz of Clapham, London.’

(8575)

Nicholas Schwartz (São Paulo, Brazil) writes to us regarding the loser of ‘The Immortal Blindfold Game’ (Alekhine v Schwartz, London, 1926):

‘My paternal grandfather, Nicolai Eugen Schwartz, was born in Riga on 20 November 1893. He was from a merchant and banking family with business interests in the Baltic States, Russia, Germany and Great Britain, and was sent to Scotland in November 1913 to study the flax, jute and hemp industries and to seek out prospective business contacts. Dundee was chosen as his base because of the city’s association with those fibre industries and because Henry W. Rennie, a fairly prosperous Dundee merchant and shipowner, was my grandfather’s godfather. Above all, Nicolai Schwartz was sent to Dundee to invest a substantial sum in Rennie’s firm.

My grandmother’s maiden name was Jeanne Catherine Carolina Marie Vernon Le Cocq: her father, John Le Cocq, of Jersey and Alderney, had married Rose Vernon.

My grandfather never returned to Riga, but remained in Dundee. He had three children: Olga Stella, who was born in 1917, Alexander Nicolai (my father), born in 1918, and Nicolai Roy (born in 1920 and killed in 1944 whilst flying for the RAF). In the 1920s the family moved to London, first to Norwood, then Streatham and ultimately to Clapham.

In London, Nicolai Schwartz frequented the Gambit Chess Rooms and Simpson’s Divan. He had been brought up to live a very easy life and he never went to work. I well remember him sitting all day long solving chess and bridge problems in books and newspapers, while smoking and drinking tea endlessly. He was always discreetly and impeccably dressed, exceptionally well mannered, invariably kind and absolutely devoted to my grandmother until the day he died, in Putney, London, on 20 March 1965.

He talked about chess much of the time, and most of his gifts to me, when I was seven or eight, were books on chess problems. I still own his Staunton chess sets, his chess boards, one of which rolled up for travelling, and his wallet-type Jaques chess set.’

We are also grateful to our correspondent for this photograph (the reverse of which states ‘Taken in Dundee 1916’):

Nicolai Eugen Schwartz

(10620)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.