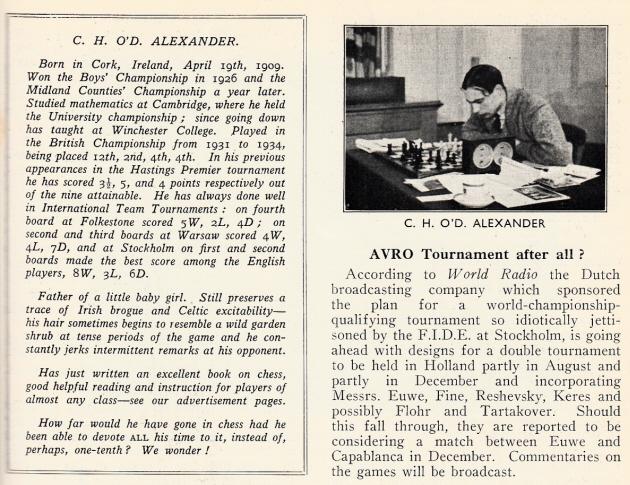

Edward Winter

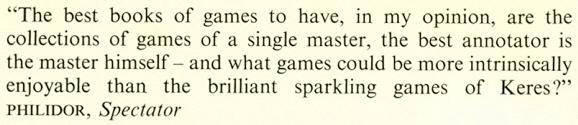

C.H.O’D. (Hugh) Alexander. Reproduced with permission from the Hulton Archive. See C.N. 6285 below.

On page 152 of the May 1953 CHESS V.W.H. Waller pointed out an interesting disagreement between leading authors over basic chess strategy:

‘Under the heading “Sicilian Defence” at page 85 of his book The Ideas Behind the Chess Openings Fine writes “White almost invariably comes out of the opening with more terrain. Theory tells us that in such cases he must attack ...” Again, on page 86 he writes “3. White must not be passive: he must attack because time is on Black’s side (it usually is in cramped positions).”

In contrast to this, C.H.O’D. Alexander in his book Chess writes at page 63 “An advantage in space is much more enduring than an advantage in time and, generally speaking, you need be in no hurry for a winning attack ...” Also on page 64 he writes “remember that when you have an advantage in space your first object is to restrict the opponent, not to launch a direct attack ...” Further, on page 66, “This game is a masterly example of using space advantage. Notice how White never hurries ...”’

The CHESS Editor then comments, ‘We rather favour Alexander’s view.’

(1540)

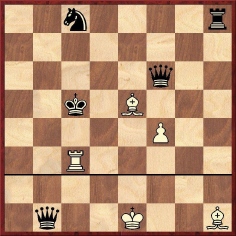

A position to ponder:

Three posers:

a) White to move and win. b) Where has this position been widely seen? c) Where has it been printed before?

(1497)

a) The winning combination is easy enough: 1 Qxb4 axb4 2 Rxa8+ Be8 3 Bxd5.b) The position was played out in an episode of the NBC television series Columbo in which the world chess champion murdered his closest rival.

c) It is given, for instance, on pages 168-169 of Winning Chess by Irving Chernev and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1948).

(1577)

Congratulations to Jack O’Keefe (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), who has discovered that the position did come from a real game:

W.J. Wolthuis – Conel Hugh O’Donel Alexander1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Qc2 Nc6 5 Nf3 d6 6 a3 Bxc3 7 Qxc3 O-O 8 g3 Ne4 9 Qc2 f5 10 Bg2 Qf6 11 e3 Bd7 12 b4 a5 13 b5 Ne7 14 Bb2 c6 15 a4 Rfc8 16 bxc6 Nxc6 17 O-O Nb4 18 Qb3 d5 19 cxd5 exd5 20 Rfc1 Rxc1+ 21 Rxc1 b5 22 axb5 Bxb5 23 Ne5 Qe6 24 Ra1 Nd2 25 Qxb4 Resigns.

The poser position was also used in a ‘Chess Quiz’ on page 21 of the June 1948 issue of Chess Review.

(1666)

See also Chess and Television.

Although not included in Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess by H. Golombek (London, 1947), the Capablanca v Fonaroff miniature is one of the Cuban’s most famous brilliancies. In a letter to us dated 11 February 1972 C.H.O’D. Alexander wrote: ‘I will certainly consider using it; the trouble is that it is so well known. If I don’t use it in the Sunday Times I may include it in my forthcoming (a year’s time) Penguin Book of Chess Positions.’

In fact, Alexander did not use the combination in that book, and ‘so well known’ is an accurate description.

(2521)

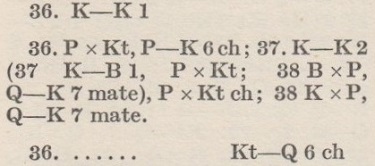

In the days when the descriptive dominated, were any prominent writers ‘letter perfect’ in their use of it? We have done a brief spot-check of two books by experienced authors and players, taking one game at random from each:

Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess by H. Golombek (Capablanca v Colle, Barcelona, 1929): Two identical moves (in algebraic 12 Rcl Rc8) are recorded inconsistently as 12 QR-B1 R-QB1. In a note to move 22 there is 29...PxP, although it could be either the c or e pawn that is captured. That was all we found, although incidental mention may be made of an error in the final note: Black is mated in three, not four, moves.

Alekhine’s Best Games of Chess 1938-45 by C.H. O’D. Alexander fell open at ‘Dr Florian v Alekhine, Prague 1942’. The game gets off to a bad start – the date should be 1943 – from which it never recovers. In the note to White’s fourth move 4 B-KB4 ought to read 4 B-QB4 and 5...B-R2 is impossible (presumably it should be 5...B-K2). Black’s fifth move in the game is recorded as 5...P-B3 although both BPs can advance. The note to White’s 15th move gives 15 PxP, although two such captures are possible. In a note to White’s 21st move we are given 23 K-B1 instead of 23 K-Kt1. Black’s 21st in the actual game should be ...KtPxB and not ...KtPxKt as stated. Black’s 32nd and 33rd moves are recorded as ...R(1)xQ and QR-B5, which mixes two different systems of distinguishing between pieces. In a note to White’s 36th move, RxQP could simply read RxP since no other pawn can be taken. Similarly, White’s 43rd move in the game should be KtxP and not KtxP(B7).

(1345)

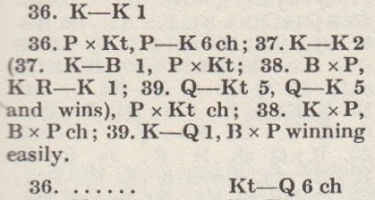

A game from page 451 of the October 1935 BCM:

Arthur William Dake – Conel Hugh O’Donel Alexander

Warsaw Olympiad, 31 August 1935

Grünfeld Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 d5 (The BCM called the opening ‘Queen’s Gambit Declined’.) 4 Bf4 Bg7 5 e3 c6 6 h3 O-O 7 Nf3 e6 8 Qb3 Qe7 9 Bd3 Nbd7 10 cxd5 exd5 11 O-O Kh8 12 Rad1 Nh5 13 Bh2 f5 14 Qc2 Nhf6 15 Ne5 Nxe5 16 Bxe5 Nd7 17 Bh2 Nb6 18 Nb1 Be6 19 Nd2 Rae8 20 Nf3 Bc8 21 Ne5 Nd7 22 f4 Nxe5 23 fxe5 a6 24 Rc1 Bh6 25 Qe2 Qe6 26 h4 Rf7 27 Bf4 Bf8 28 Qe1 h6 29 Rc2 Kg7 30 h5 Kh8 31 hxg6 Qxg6 32 Qh4 Rh7 33 Rcf2 Be7 34 Qh3 Rf8 35 Bg3 Bg5 36 Bh4 Rhf7 37 Bxg5 Qxg5 38 Rf4 Qg6 39 Rh4 Kg7 40 Rf3 Qe6 41 Rg3+ Kh7

Here the BCM concluded as follows: ‘42 R-Kt4! [sic] Resigns. The threat is RxPch, followed by R-R4, a clever finish to a good game by Dake against a stiff opposition.’

All other sources found so far state that the finish was 42 Qg4 Resigns. 42 Rgg4 is weaker, as it would allow Black to hold on with 42…Rg7.

(3305)

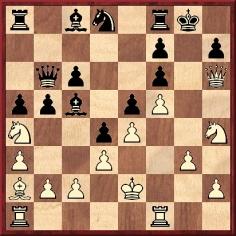

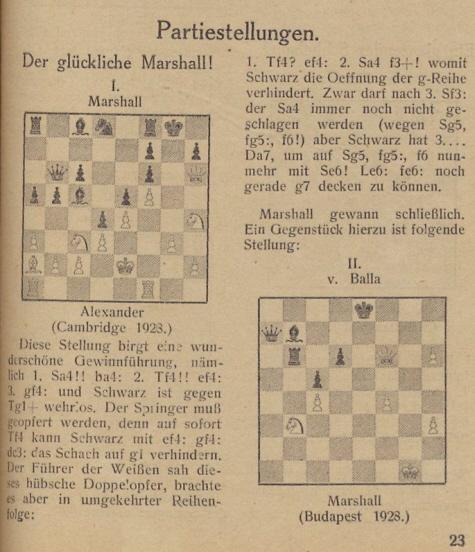

This position appears on page 166 of L’oeil tactique: l’entraînement à la combinaison by E. Neiman (Paris, 2003) and is merely labelled ‘Alexander – Marshall 1928’. The book notes that after 1 Rf4 exf4 2 gxf4 dxc3 Black would control g1, and the winning line is therefore given as 1 Na4 bxa4 2 Rf4 exf4 3 gxf4, after which 4 Rg1+ leads to mate.

An innocent reader might assume that the players were C.H.O’D. Alexander and F.J. Marshall. That, indeed, is the impression given by various later editions of Kombinationen by K. Richter (see position 297 and the index references). Already in the first edition (Berlin, 1936) Richter gave the position (see page 114), stating that the game went 1 Rf4 exf4 2 Na4 f3+ 3 Nxf3 Qa7 4 Ng5 fxg5 5 f6 Ne6 6 Bxe6 fxe6. As a caption Richter put ‘Meisterturnier Cambridge 1928’, an event unknown to us. C.H.O’D. Alexander went up to Cambridge University that year, but was he necessarily the Alexander in question? Other players active around that time were F.F.L. Alexander and L. Alexander, and there was also an E.T. Marshall; on page 162 of the April 1932 BCM all three of them were listed as members of the Lud-Eagle team.

At the moment no information can be offered about where the game was played or by whom. Nor has the complete score been found.

(3508)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) proposes a tentative reconstruction of the early part of the game, to reach the starting-position currently known:

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 d3 O-O 5 Bg5 c6 6 f4 d6 7 Nf3 b5 8 Bb3 a5 9 a3 Qb6 10 Bxf6 Bf2+ 11 Ke2 gxf6 12 Qd2 Na6 13 Ba2 Nc7 14 g3 Ne6 15 f5 Nd8 16 Rhf1 Bc5 17 Nh4 d5 18 Qh6 d4 19 Na4.

(5262)

Information is still sought about the position discussed in C.N. 3508 and, in particular, about the identity of the players.

It was also published (with the specification C.H. Alexander) on page 47 of volume one of Taktika Moderního Šachu by L. Pachman (Prague, 1962):

The position was not included in the English version, Modern Chess Tactics (London, 1970).

(6624)

On pages 107-108 of Alfil malo by B. Ivkov (Barcelona, 2002) the date of the Alexander v Marshall position is given as 1938, not 1928. With regard to the quest for the full game-score, is that an error or a clue?

Certainly, prudence is required with the book, a Serbo-Croatian work translated into Spanish. Its overall unreliability may be gauged from some of the names featured: Edw. Asker, Dechapel (in a game against Labourdonet), Fisher (passim and, for instance, in the game D. Bern-Fisher), Korchno, Kreychik, Kreytschik, Mardhall, Nimzowits, Pilsburry, Schlehter, Semish, Shlechter (a game dated 1860), Smislosv, Spielman, Spilmann, Tall, Tarasch and Tarash.

(6653)

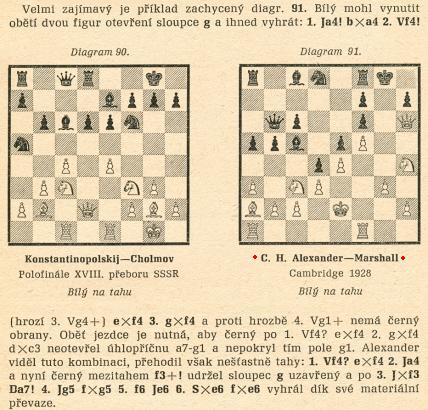

At last a 1920s source has been found, by Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada). From page 23 of Schachwart, February, 1929 (a magazine edited at that time by Kurt Richter):

(6747)

C.N. 3508 opened a discussion of an Alexander v Marshall game (‘Cambridge, 1928’), the main point of interest being this position:

After 1 Rf4 exf4 2 gxf4 dxc3 Black controls g1, and the winning line was therefore given as 1 Na4 bxa4 2 Rf4 exf4 3 gxf4, after which 4 Rg1+ leads to mate.

Not until C.N. 6747 could a source from the 1920s be presented, but now the full details of the game have been found by Alan Smith (Manchester, England):

Conel Hugh O’Donel Alexander – E.T. Marshall

Cambridge University v Lud-Eagle match, 1 December 1928

Vienna Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Bc5 3 Bc4 d6 4 d3 Nc6 5 f4 Nf6 6 Nf3 O-O 7 f5 Na5 8 Bg5 c6 9 a3 b5 10 Ba2 Qb6 11 Qe2 Nb7 12 Nh4 a5 13 Bxf6 gxf6 14 Rf1 Be3 15 Qh5 Bf4 16 Nd1 Nd8 17 g3 Be3 18 Ke2 Bc5 19 Qh6 d5 20 Nc3 d4 21 Rf4 exf4 22 Na4 f3+ 23 Nxf3 Qa7 24 Nxc5 Bxf5 25 g4 Bg6 26 Nxd4 Qxc5 27 Nf5 Bxf5 28 gxf5 Ne6 29 c3 Qe7 30 fxe6 fxe6 31 Rg1+ Kh8 32 Bxe6 Rae8 33 Bf5 Rg8 Drawn.

Sources: The Observer, 16 December 1928, page 25, with details concerning the match in The Times, 3 December 1928.

(7103)

John Nunn discussed the game on pages 37-38 of the August 2023 issue of Chess Moves.

Vidmar’s view, quoted in C.N. 3518, that in 1936 Kashdan was ‘the most talented player in America’ reminds us of a dramatic win by Kashdan the following year and a strange story recounted by I.A. Horowitz on page 8 of his book All About Chess (New York, 1971):

‘Carrie Marshall, widow of longtime United States chess champion, Frank Marshall, won a game for the USA in the International Team Tournament at Stockholm in 1937.

The match was USA v England, and the particular board was Kashdan, USA, against C.H.O. “Death” Alexander, the English

Kashdan was hopelessly “busted”. Carrie, however, had suggested that a necklace which carried an image of Our Lady of Fatima could bring him luck if rubbed and petitioned. To oblige, Kashdan went through the motions, and Alexander instantly blundered away a piece and the game.

This win for Kashdan cost me a fat 50 dollars, a prize put up by Washington industrialist I.S. Turover for the American making the best score for the United States team.’

Below is a photograph of (left to right) Mrs Kashdan, I.I. Kashdan, F.J. Marshall, I.A. Horowitz and Mrs Marshall, with the Hamilton-Russell Cup:

It has not been possible to reconcile all the details of the above story with the game itself, which was annotated by C.H.O’D. Alexander on pages 567-569 of the November 1937 BCM and by the world champion, Max Euwe, on pages 21-23 of CHESS, 14 September 1937. Below is the complete score, with a digest of their notes to the concluding phase:

Conel Hugh O’Donel Alexander – Isaac Irving Kashdan

Stockholm Olympiad, 12 August 1937

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O d6 6 Bxc6+ bxc6 7 d4 Nd7 8 b3 Be7 9 Bb2 f6 10 Nh4 g6 11 Qe2 f5 12 dxe5 Bxh4 13 e6 Nf6 14 Qc4 c5 15 e5 Ng4 16 Qd5 Rb8 17 exd6 Bb7 18 d7+ Kf8 19 Qc4 Bf6 20 Bxf6 Nxf6 21 Qxc5+ Kg7 22 Nc3 Ng8 23 Rad1 h6 24 Rfe1 (Alexander did not comment on this, whereas Euwe called it ‘a good move but not the strongest’. He offered analysis to show that after 24 e7 Nxe7 25 Rfe1 there would be ‘a speedily decisive attack’. Annotating the game on pages 234-235 of the August 1937 Wiener Schachzeitung, Spielmann gave 24 Rfe1 a question mark and, like Euwe, indicated that 24 e7 would win.) 24...Ne7 25 Qe5+ Kh7 26 Na4 Rf8 27 f4 (Alexander: ‘To stop ...f4, but the rook gets in on the g-file. Both sides were now very short of time, each having 23 moves to make in about 15 minutes.’ 27...Rg8 28 Nc5 g5 29 Nxb7 Rxb7 30 c4 gxf4 31 Qxf4 Rg6 32 Qh4 Rb8 33 Re5 Qf8 34 Qf2 Rd8 35 Qc5 c6 36 Rf1 Qg7 37 Re2 Rg8

38 g3 (Alexander: ‘A blunder, but White has lost the grip of the position. 38 Rff2 might be good enough to draw, however (38...Qa1+ forces draw if Black wishes).’ Euwe: ‘This is the move which actually loses the game.’) 38...Rxg3+ 39 Kh1 (Alexander: ‘39 hxg3 Qxg3+ 40 Kh1 Qh3+ 41 Rh2 Qxf1+ 42 Qg1 Qxg1 mate.’) 39...Rg6 40 Qb6 (Neither Alexander nor Euwe commented on this move, but Euwe gave it a question mark.) 40...Rxe6 41 Rg1 Rxe2 (Alexander: ‘41...Qxg1+ 42 Qxg1 Rxg1+ 43 Kxg1 and wins.’ Euwe: ‘Kashdan has defended in an exceedingly difficult situation as well as he possibly could and now, as soon as he gains the advantage, thrusts it home inexorably.’) 42 Rxg7+ Rxg7 43 h4 (Alexander: ‘43 h3 would still draw as Black has nothing better than perpetual check.’) 43...Re1+ 44 Kh2 Re2+ 45 Kh3 (Alexander: ‘Seeing that 45...Ng6 could be met by 46 Qd4 winning, and completely overlooking the move played; but if 45 Kh1 Re4 46 Qf2 Rg8 and Black wins fairly easily.’ He gave 45 Kh3 two question marks, whereas Euwe, who presented the same line, appended only one.) 45...f4 46 White resigns. (Alexander: ‘A splendidly cool defence by Kashdan after his opening mistake; Black’s play when in time difficulties was extraordinarily accurate.’)

The game was also annotated by W.H. Cozens on pages 41-44 of his posthumous book The Lost Olympiad (St Leonards on Sea, 1985).

(3523)

No move in the game corresponds to Horowitz’s reference to a blunder losing a piece. As regards his assertion about the best-score prize offered by Turover, below is a paragraph from page 235 of the October 1937 Chess Review:

(10487)

C.J.S. Purdy was a consummate chess teacher, and it is therefore of interest to note his choice of ‘the very best beginner’s book’, on page 157 of Chess World, October 1963. Below is an abridged version of his remarks:

‘Is there one beginner’s book that is better than all the others? ... Up till now we have never had a sure answer ... Now we have. It is Learn Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander and T.J. Beach. ... There is not one ambiguous or difficult sentence, or even word, in the whole book. ... We seldom praise a book so highly. We think most chess books have something good in them and are worth reading despite a percentage of twaddle. But here is a book which, for the players it’s intended for, is 100% good. Don’t forget, it is for genuine beginners, not for near-average players. It is excellent for children, and excellent for adults.’

Learn Chess was first published in 1963, in two volumes. It has been republished a number of times, e.g. by Cadogan Chess in 1994 as a single volume (algebraic notation).

(4017)

Purdy reiterated his recommendation (‘the very best book of both theory and practice for raw beginners’) on page 121 of the July-August 1967 Chess World, as well as on the inside front cover of the September-October 1967 issue, where he added:

‘The inexperienced player loses mainly by sheer oversights. He has no “sight of the board”. Nothing is obvious to him. What is wanted is a book to remedy this, and the only way is to concentrate on the “little combinations” that must be seen before you can play at all sensibly. Mere understanding of positional principles helps a bit but not much.

... As we always say, the best books for learners are those that are both theory and practice combined, and we’d add more practice than theory.’

The present-day publisher of Alexander and Beach’s work (two volumes in one) is Everyman Chess.

(9813)

Alan McGowan writes:

‘See CHESS, February 1945, page 73, for a report of a 12-board match on 2 December 1944 between Oxford University Chess Club and Bletchley Chess Club. The Bletchley team (which won 8-4) included C.H.O’D. Alexander and H. Golombek on boards 1 and 2. Board 3 featured J.M. Aitken, board 4 was I.J. Good, and board 5 was occupied by N.A. Perkins. Full team details were given, as well as a photograph of the players:

An article based on this information was published on pages 10-11 of Scottish Chess, June 2005.’

Milner-Barry was not mentioned in the CHESS report. As regards his surviving papers, Leonard Barden (London) draws our attention to their location. [Replacement link.]

(4034)

See also Chess and the Code-Breakers, which includes the following references from Ulrich Tamm (Enger, Germany):

A personal memoir of Alexander by Milner-Barry;

An in memoriam article on Alexander by Hugh Denham.

Our correspondent also notes that the work of Alexander and Milner-Barry at Bletchley Park was described in the book The Hut Six Story by Gordon Welchman, and in an article by John A.N. Lee and Golde Holtzman, ‘50 Years After Breaking the Codes: Interviews with Two of the Bletchley Park Scientists’, on pages 32-43 of the 1/1995 issue of IEEE Annals of the History of Computing.

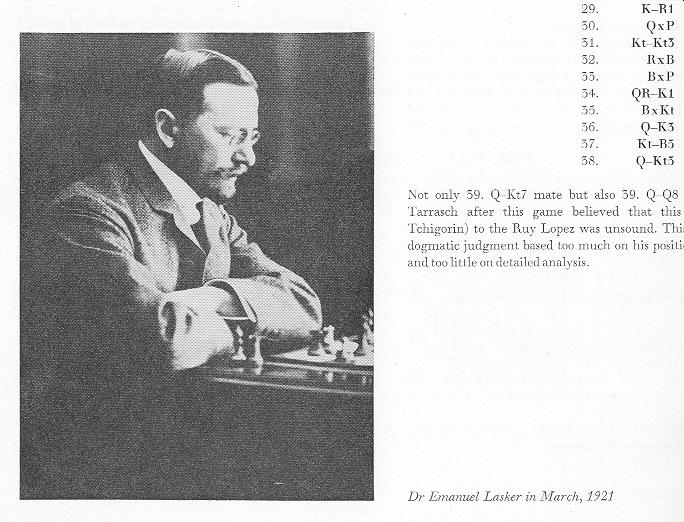

This illustration appeared on page 60 of A Book of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1973):

In reality, both parts of the caption (‘Dr Emanuel Lasker’ and ‘in March, 1921’ are wrong. As noted on page 315 of A Chess Omnibus, the player is Tarrasch. We add here that the photograph was the frontispiece of Schachjahrbuch für 1908 by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1909), whose caption correctly identified the two masters and noted that the picture had been taken in Munich during their 1908 world championship match.

(4221)

See too Chess: Mistaken Identity.

This position comes from page 26 of Alexander on Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1974):

Alexander’s caption reads:

‘Three examples of the skewer. White bishop skewers R through the Q and the White rook skewers Kt through the K; Black Q skewers B through K at bottom of diagram.’

(4231)

The following passage from page 16 of C.H.O’D. Alexander’s A Book of Chess (London, 1973) is worth noting:

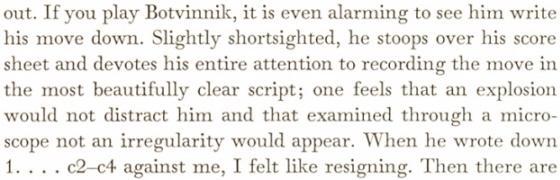

‘If you play Botvinnik, it is even alarming to see him write his move down. Slightly shortsighted, he stoops over his score sheet and devotes his entire attention to recording the move in the most beautifully clear script; one feels that an explosion would not distract him and that examined through a microscope not an irregularity would appear. When he wrote down 1...c2-c4 [sic] against me, I felt like resigning.’

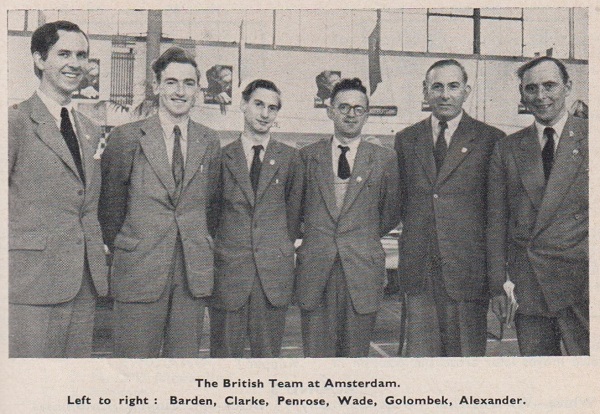

We take the game in question to be Alexander v Botvinnik in the Amsterdam Olympiad of 1954, a Sicilian Defence.

(4292)

From page 102 of the 4/2009 New in Chess (in an article by Hans Ree):

‘... I was reminded of a remark about Botvinnik that is attributed to C.H.O’D. Alexander: “When he wrote down 1 c2-c4 against me I felt like resigning.” By the way, Botvinnik never played 1 c4 against Alexander (against me he did), so this might seem an instance of the threat being stronger than the execution, but only if you believe the impossible: that Botvinnik would ever write down a move that he was not going to play.’

This episode was discussed briefly in C.N. 4292, where Alexander’s exact words were quoted, from page 16 of A Book of Chess (London, 1973):

Reviewing the work on page 63 of the February 1974 BCM (the month Alexander died), A.J. Roycroft wrote:

‘... I shall content myself with wagering that what Botvinnik wrote on his scoresheet with such a degree of intimidating concentration that Alexander, as White, felt like resigning on the spot was not (page 16) “1...c2-c4” but 1...c7-c5.’

In C.N. 4294 we suggested that the contest in question was Alexander v Botvinnik, Amsterdam, 1954, but the players’ game at Nottingham, 1936, also a Sicilian Defence, is a no less plausible candidate. Alexander provided brief notes on page 59 of CHESS, 14 October 1936, but said nothing until move ten. Do his other writings shed any further light on the Botvinnik c4/c5 matter?

(6185)

See also C.N. 6596 below, concerning Amsterdam, 1954.

CHESS, 2 October 1954, page 37

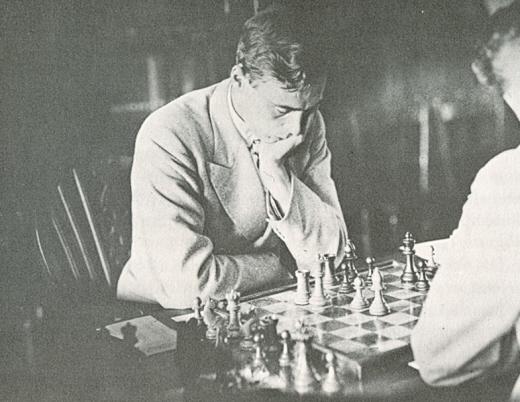

This photograph was published on page 12 of The Encyclopedia of Chess by H. Golombek (London, 1977) with the caption ‘C.H.O’D. Alexander in play against Sultan Khan, Hastings, 1933/4’. By the time of that tournament Sultan Khan had left Europe, and the event in question was the British Championship in Hastings, July-August 1933. The game was given on pages 129-130 of Mir Sultan Khan by R.N. Coles (St Leonards on Sea, 1977):

Sultan Khan – Conel Hugh O’Donel Alexander

Hastings, 1 August 1933

Grünfeld Defence

1 c4 Nf6 2 Nc3 g6 3 d4 d5 4 Bg5 Be6 5 Qb3 dxc4 6 Qxb7 Nbd7 7 Nb5 Nd5 8 e4 Rb8 9 Qc6 Rb6 10 Qxc4 a6 11 exd5 axb5 12 Qb3 Bf5 13 Bxb5 Bg7 14 Ne2 O-O 15 a4 Nf6 16 Nc3 Ne4 17 Be3 Nd6 18 Qa2 Nxb5 19 axb5 Bd3 20 Qb3 Qd7 21 Ra5 Rfb8 22 Qa4 Bxb5 23 Nxb5 Rxb5 24 Rxb5 Qxb5 25 Qxb5 Rxb5 26 Kd2 Rxd5 27 Kd3 Rb5 28 Rc1 Rxb2 29 Rxc7 Bf8 30 d5 Rb8 31 Bc5 Re8 32 Kc4 Kg7 33 g4 g5 34 Kb5 Kf6 35 Bd4+ Kg6 36 Kc6

36...Rd8 37 Bc5 Kf6 38 h3 h6 39 Bb4 Rb8 40 Rb7 Rxb7 41 Kxb7 Ke5 42 Kc6 f5 43 Bc3+ Ke4 44 gxf5 Kxf5 45 Kd7 Ke4 46 Ke8 Kxd5 47 Kxf8 Resigns.

(6285)

Robert Desjarlais (Bronxville, NY, USA) asks for information about a quote often ascribed to Alekhine, although without any reliable source:

‘During a chess competition a chess master should be a combination of a beast of prey and a monk.’

There are textual variants, but the above wording had a page to itself (88) in Bruce Pandolfini’s Treasure Chess (New York, 2007). Of itself, that naturally proves nothing (C.N. 5280 shows why), and we do not recall seeing the sentiments expressed in Alekhine’s writings.

There is, though, the following ‘once’ version on page 8 of Blunders and Brilliancies by Ian Mullen and Moe Moss (Oxford, 1990):

‘Alekhine was once quoted as saying that the successful tournament player must combine the chief characteristics of a research scientist, an ascetic monk and a beast of prey.’

At Google Books we found this sentence about Alekhine in an article ‘Chess Masters in Action’ by C.H.O’D. Alexander published in the Irish Digest, 1959:

‘Playing him, one gets a strong sense of someone dedicated to the game – a mixture of monk and scientist.’ [In fact, Alexander was writing about Botvinnik. See C.N. 6596 below.]

Only a snippet of Alexander’s text is available on-line, and we shall be grateful to any reader who can supply the full article – and especially since it seems also to contain information of relevance to the Alexander v Botvinnik c4/c5 matter (C.N.s 4292 and 6185).

Alexander Alekhine

(6587)

We have acquired the full article ‘Chess Masters in Action’ by C.H.O’D. Alexander, which was published on pages 79-82 of the Irish Digest, October 1959. Extracts are provided below, and there is a surprise concerning the monk/scientist quote attributed to Alekhine (C.N. 6587).

‘Dr Emanuel Lasker, world champion for 27 years from 1894, I met in 1936 when he was well on in the 60s and far past his best, though still good enough to dispose of me. A rather small man with strong aggressive features, he produced even at that age a tremendous impression of toughness and of an endlessly resourceful fighting spirit; I have always thought him the greatest tournament player of all time.

He was unrivalled in his ability to win lost games – he never gave up hope and he had a genius for making his opponents play the kind of positions that did not suit them. He would get the steady players into positions where adventurous play was needed and the brilliant players into positions where consolidation was required; you were never allowed to be comfortable against Lasker.’

‘Capablanca ... had an Olympian attitude to the game and his opponents; he knew he was better than you and since he proposed to play the correct moves (all of which were pretty obvious, anyway) he did not anticipate much difficulty in demonstrating it. If things had been a little harder for him he might in the end have been an even greater player, and better able to resist the impact of a player of equal genius and a greater passion for the game – Alexander Alekhine.’

‘Capablanca knew he was much better than anyone else and took it for granted; Alekhine never quite believed it and was always out to demonstrate it yet again to reassure himself. An intensely nervous, dynamic character, the way he moved his pieces was almost like a physical attack. Capablanca gave you the impression that disposing of you was a piece of routine, to be got over as quickly as possible; Alekhine, you felt, intended to give you a lesson you would not quickly forget for your impertinence in daring to oppose him.

I remember a curious incident in one of my games with Alekhine. Someone told me that when Alekhine was worried about his position he always twisted his hair with his fingers. In 1938 I played Alekhine in the Margate tournament and he made what looked to me like a weak move in the opening; I made my reply with a nervous feeling that I had probably overlooked something. What was my delight to see Alekhine, after a minute or two’s reflection, start to twist his hair.

This was about 10.0 a.m., and from then till 2.30 (it was the last day of the tournament and no adjournment for lunch allowed) Alekhine sat without leaving the board, and through all the turns of a complex game continued (to my great moral support) to twist his hair.

At 2.30 I made a slight tactical error and let my advantage slip; Alekhine moved, took a comb out of his pocket, ran it through his hair, got up, and walked up and down the tournament room. My own judgment (that my advantage was gone) was thus confirmed as clearly as if he had told me so, and I took an immediate opportunity to force a draw before worse befell me.’ [Alexander’s notes to the game are on pages 75-77 of the Golombek/Hartston monograph on him, having originally appeared on pages 282-283 of the June 1938 BCM. The photograph below was published on page 266 of the same issue of the BCM.]

‘For me, Alekhine will always epitomize chess, and I shall always remember my games with him with pleasure, even though he did win a brilliancy prize against me for one of them.’

‘[Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine] all had a genius for the game. Euwe, though he had great natural talent, always struck me as essentially a man of high all-round ability who systematically devoted this ability to making himself a great chessplayer.

Everything that could be learnt about chess Euwe learnt, and taught to others ...’

‘Smyslov, a big slow-spoken redhead in the middle 30s who looks more like a Scot than a Slav, has a style as massive as his personality; after being beaten by Smyslov you feel as if you have been run over by a steamroller.’

‘Botvinnik is in the greatest tradition of world champions, with Morphy, Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine. Playing him, one gets a strong sense of someone dedicated to the game – a mixture of monk and scientist. When I played Botvinnik in Amsterdam in 1954 I was temporarily demoralized by watching him write down his first move. Slightly short-sighted, he gave his entire attention to recording the move in the most beautifully clear and precise script; only after completing this to his entire satisfaction did he again bend his mind to the game. This calm but intense concentration on even the most trivial aspect of the game made me feel like a fly under the scientists’ microscope.’

From that final extract it can be seen that (contrary to the impression derived from the Google Books snippet) the description ‘a mixture of monk and scientist’ concerned Botvinnik, not Alekhine. Nonetheless, as noted in C.N. 6587 the Mullen/Moss book Blunders and Brilliancies claimed that Alekhine had referred to ‘a research scientist, an ascetic monk and a beast of prey’.

C.N. 6587 also mentioned the possible relevance to C.N.s 4292 and 6185 of Alexander’s remark about how Botvinnik wrote down his first move.

The Irish Digest stated on page 79 that the article by Alexander was ‘condensed from The Listener’.

(6596)

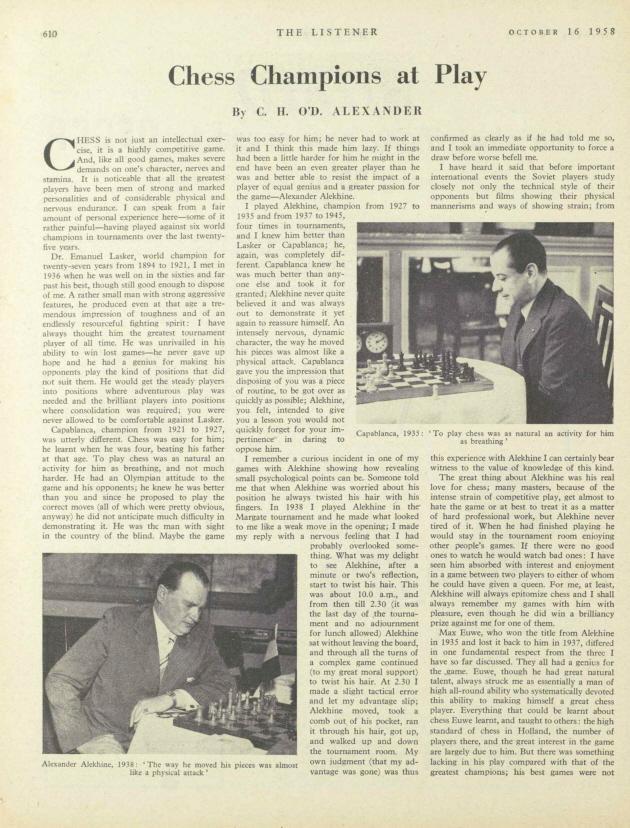

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found the full, original version of C.H.O’D. Alexander’s article, on pages 610-611 of The Listener, 16 October 1958:

The ensuing correspondence published in The Listener (6 November 1958, page 741 and 13 November 1958, page 786) focused on Edgar Allan Poe:

(8138)

In a letter to us dated 11 February 1972 C.H.O’D. Alexander wrote:

‘Capa was undoubtedly one of the two or three most gifted players who ever lived – but lazy (that’s why Alekhine beat him). Nowadays he would have to work much harder – especially at the openings – than he did. I think Fischer is equally gifted (his style is very much like Capa’s) and a much harder worker; so in fact I put Fischer ahead of him. I’m now inclined to think Fischer the best there has ever been.’

We subsequently asked Alexander how he would place the other main contenders for the title of greatest player ever, to which he replied:

‘Very close – probably 1 Lasker 2 Botvinnik, Capablanca 4 Alekhine, but there are so many different ways of defining “greatest player” which give different answers.’

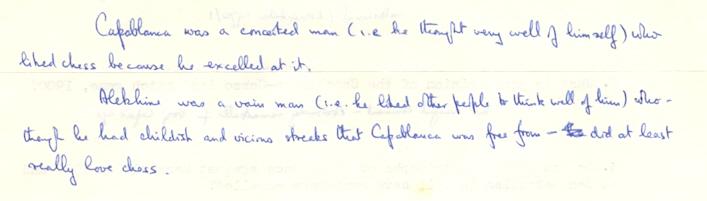

As regards Capablanca and Alekhine’s respective characters, Alexander informed us:

‘Capablanca was a conceited man (i.e. he thought very well of himself) who liked chess because he excelled at it.

Alekhine was a vain man (i.e. he liked other people to think well of him) who – though he had childish and vicious streaks that Capablanca was free from – did at least really love chess.’

(4293)

The quote below, from an obituary of Sir Maurice Kendall, comes from Morgan Daniels (London):

‘Life at St John’s was in striking contrast to that in Derby, and Maurice’s naturally gregarious nature brought him several circles of friends apart from the group reading Mathematics at St John’s: he played cricket for his college (and indeed was still a useful medium-paced bowler 25 years later); and he might have got a half-blue at chess had the company been less select – C.H.O’D. Alexander, later twice British champion, was one, and Jacob Bronowski another. Typically, Maurice enjoyed playing chess blindfold, and Bronowski and he played “negative chess”, where the previous moves had to be deduced from a set position.’

Source: A. Stuart, ‘Sir Maurice Kendall, 1907-1983’ in the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General), Volume 147, Number 1 (1984), page 121.

(4971)

C.N. 4863 asked about the first occurrence in a chess context of the phrase often attributed to Botvinnik, ‘Every schoolboy knows that ...’.

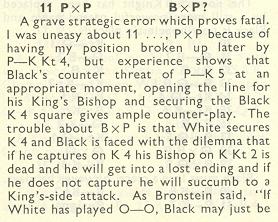

Taking up a lead from Norman Stephenson (Middlesbrough, England), who had a recollection of the remark in a UK chess magazine in relation to the game Botvinnik v Alexander, Munich Olympiad, 1958, we have found surprising passages in both CHESS and the BCM.

On page 30 of CHESS, 1 November 1958 P.H. Clarke wrote regarding round eight of the Olympiad finals:

‘England were beaten by the same margin as at Moscow [+0 =0 –4, as in the 1956 Olympiad]. Botvinnik won instructively.

All the Russians were horrified by Alexander’s 11th move, after which his game was strategically lost. Bronstein remarked, with some exaggeration, that every Russian schoolboy knows you must recapture with the pawn!’

C.H.O’D. Alexander annotated his loss on pages 30-31 of the January 1959 BCM, and below is a diagram of the position after 11 exf5, together with Alexander’s note on his reply, 11...Bxf5:

![]()

Alexander’s final words in this note are worth pondering:

‘As Bronstein said, “If White has played O-O, Black may just be able to afford BxP but if he has not it is fatal” – and every Russian schoolboy knows this!’

Were it not for what P.H. Clarke wrote in CHESS, we would automatically interpret the ‘schoolboy’ remark as Alexander’s own addition to the words of Bronstein which he had just quoted.

It is still unclear why the remark has been ascribed to Botvinnik. On page 113 of volume three of his trilogy Shakhmatnoe Tvorchestvo Botvinnika (Moscow, 1968) Botvinnik described 11...Bxf5 as ‘a typical strategic error in the King’s Indian Defence’ and stated that 11...gxf5 was forced, but made no reference to schoolboy knowledge:

(4891)

From Leonard Barden:

‘I was in Munich in 1958, and my memory is that Bronstein made the “schoolboy” remark. It is the type of phrase characteristic of Bronstein but not typical of Botvinnik. I can dimly recall Alexander retailing the criticism, with some zest.’

(4896)

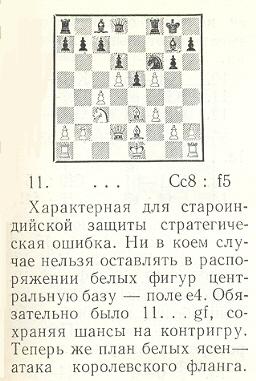

Hans-Georg Kleinhenz (Munich, Germany) writes:

‘A predecessor of the famous “every schoolboy knows” quote can be found in the Carlsbad, 1907 tournament book (page 287), where Georg Marco comments on the opening moves of Leonhardt v Wolf:

“Die bisherigen Züge sind jedem A-B-C-Schützen [a pupil in the earliest class at school, who is learning the alphabet] aus dem kleinen Dufresne bekannt.”’

We note that the English-language edition of the tournament book (Yorklyn, 2007) has a curious mistranslation:

‘These moves have been known to every beginner since the days of the young Dufresne.’

The phrase ‘kleinen Dufresne’ (‘little Dufresne’) has nothing to do with Dufresne’s age (or size). Marco was stating that the opening moves of Leonhardt v Wolf were well-known owing to their inclusion in Dufresne’s ‘little’ introductory manual (Kleines Lehrbuch des Schachspiels).

(5367)

From page 176 of the June 1939 issue of the Tijdschrift van den Koninklijken Nederlandschen Schaakbond:

The occasion was the match between Holland and England in the Hague, 28-29 May 1939.

(5116)

Golombek was not always sure of his own playing record. In The Times on 8 November 1975 (page 11) he wrote:

‘I well remember the late Hugh Alexander asking me many years ago what were my results in my games against Sir George Thomas. I replied I was not sure but believed I was one or two up. Whereupon he laughed and said that was exactly the reply Sir George had given him when asked what his results were with Golombek.’

His column on 16 July 1977 (page 10) praised Alexander highly, noting that at Hastings, 1937-38 he had finished equal second with Keres, below Reshevsky but above Fine and Flohr:

‘Had events pursued their normal course I am now convinced that Alexander would have got very near the world title. The quality of his chess was rising all the time, and his knowledge of the technical part of the game continually deepening.

But then came the Second World War.’

(5215)

C.H.O’D. Alexander

A passage by C.H.O’D. Alexander from his Sunday Times column on page 82 of the Supplement, 8 April 1973:

‘Punch-drunk at the moment from struggling with my games in the World Team Final I am incapable of annotating anyone else’s games; here, therefore, is one of my own [against Ulyanov] from a Cheltenham v Sochi friendly match. Friendly – yes I suppose so; but not conducted in any spirit of levity or undue haste. One of our team went round the world by sea in the middle and only got two moves behind the rest of us; and while I won this game in the comparatively short time of 2½ years, in my other game against Ulyanov I have been on the defensive for four years – I hope to equalize any year now.’

(5249)

Vladimir Neistadt reverts to C.N. 5249, which quoted from C.H.O’D. Alexander’s Sunday Times column on page 82 of the Supplement, 8 April 1973:

‘Punch-drunk at the moment from struggling with my games in the World Team Final I am incapable of annotating anyone else’s games; here, therefore, is one of my own [against Ulyanov] from a Cheltenham v Sochi friendly match. Friendly – yes I suppose so; but not conducted in any spirit of levity or undue haste. One of our team went round the world by sea in the middle and only got two moves behind the rest of us; and while I won this game in the comparatively short time of 2½ years, in my other game against Ulyanov I have been on the defensive for four years – I hope to equalize any year now.’

Our correspondent asks to see the game published by Alexander, and requests any further information about the match between Cheltenham and Sochi (the places were twinned), such as the other participants’ names.

Below is the score of the Alexander v Ulyanov game published, with notes, in the Sunday Times, and dated 1968-70:

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 a6 6 Bc4 e6 7 Bb3 Be7 8 f4 O-O 9 f5 e5 10 Nde2 Nc6 11 Be3 b5 12 Nd5 Nxe4 13 O-O Rb8 14 c3 Bg5 15 Qd3 Nc5 16 Bxc5 dxc5

17 f6 c4 18 Qg3 h6 19 Rad1 cxb3 20 h4 Kh7 21 fxg7 Kxg7 22 Rf6 bxa2 23 hxg5 Qxd5 24 Rxd5 a1(Q)+ 25 Rf1 Qxf1+ 26 Kxf1 h5 27 Rd6 Resigns.

Alexander also discussed the match on page 98 of A Book of Chess (London, 1973), published shortly before his death:

Acknowledgement: Cleveland Public Library

In the introduction to the 8 April 1973 Sunday Times column, Alexander gave some general observations on postal play:

‘Though much correspondence play, even at international level, is surprisingly bad, playing C.C. makes one realize that chess is difficult; I can take as much time as I like and still get it wrong. Apart from oversights (you make those after two hours’ thought as well as after two minutes’) there are three causes of failure. First, inadequate opening knowledge; how many innocents come to grief through trustingly following MCO on the assumption that it must be right. Next lack of imagination – you simply fail to see a possible line. Most important, faulty judgement; one weighs up positions wrongly.’

(12068)

From C.H.O’D. Alexander’s Foreword (pages v-vi) to the anthology of prose and verse King, Queen and Knight by N. Knight and W. Guy (London, 1975):

‘... I should like to add one remark addressed especially to the stronger players. When we are soaked in chess, completely involved in its technicalities, we lose something; we forget what it was like when we first learnt this mysterious, inexhaustible, implacable art/game/science. Seeing chess – both in itself and in its numerous usages as an analogue of larger things – through the eyes of those who may be inexpert players but are highly articulate and intelligent men and women, we can perhaps regain some of the freshness of feeling that we once had.’

(5458)

‘Error is the lifeblood of chess’, wrote C.J.S. Purdy on page 52 of the 1 March 1949 issue of Chess World concerning the following position:

White to move

The full paragraph was:

‘Error is the lifeblood of chess. Not only must the greatest masters inevitably make errors in play, but also writers in books – unless they confine themselves to exceptionally easy positions.’

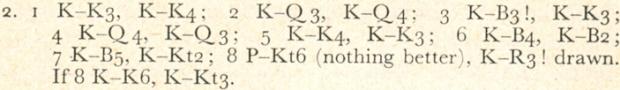

After praising C.H.O’D. Alexander’s Chess (first published in 1937 and reissued in the 1940s), Purdy noted that Alexander had given the position on page 109 and the following solution on page 120:

On page 72 of his magazine Purdy commented:

‘Most errors in analysis arise through taking something for granted. In chess, you must always be taking something for granted, or you could hardly ever come to a decision at all – hence the inevitability of error. On move 7, Alexander has assumed as a matter of course that the white king will take the opposition. We are all taught that the opposition is the great desideratum in pawn endings. The trouble is that every generalization in chess breaks down – sometimes. Here White can win by deliberately giving Black the opposition, temporarily.

Thus, 7 K-K5! This enables White to force the win of the black pawn and win easily, e.g. 7...K-N2 8 K-B5 K-B2 9 P-N6ch, etc. Or 7...K-K2 8 P-N6.

After 7 K-B5 K-N2 the book says White has “nothing better” than 8 P-N6. This, again, is wrong; with a little shuffling, White can “change the move” and still win, e.g. 8 K-K5 K-B2 9 K-Q6 K-N2 10 K-K7 K-N3 11 K-K6 K-N2 12 K-B5, etc. Indeed, with the pawns as diagrammed, White can win no matter where the kings are.

But in the diagram, if you move all the pawns [and the kings, of course] one rank or two ranks nearer to Black’s side, then it really is a draw.

Here we have two paradoxes: (a) that taking the opposition on move 7 is bad, (b) that if White is nearer queening he is worse off. Both paradoxes arise because of the law of stalemate, which is itself paradoxical.

These draws nearly always involve a rook’s pawn. There is one exception. In the diagram move the pawns two ranks nearer Black’s side and one file to the left – still a draw. If you take all these statements for granted, they are well-nigh useless; all should be verified, which is quite easy, and you will then really benefit.’

It seems that Purdy’s correction did not come to Alexander’s attention, for the faulty solution still appeared on page 105 of the final edition of his book, Alexander on Chess (London, 1974).

A mirror image of the same pawn ending (demonstrated as a win) was given on page 42 of volume four of Comprehensive Chess Endings by Y. Averbakh and I. Maizelis (Oxford, 1987).

(5479)

From Chess and Radio:

Pages 57-58 of CHESS, 29 November 1958 had an article entitled ‘Chess on the Air’. The first paragraph:

‘Starting at seven p.m. each Tuesday since the end of September, the BBC has given us a half-hour of chess. Never before in the history of British broadcasting has chess had such a show. Previously, it has been inexcusably neglected: only angling – equally numbering hundreds of thousands of devotees but equally hard to “put over” on the air – has suffered so badly.’

A game between listeners and C.H.O’D. Alexander was published on pages 227-230 of CHESS, 23 May 1959.

Peter Morris (Kallista, Victoria, Australia) notes that ‘favourite games’ were presented on pages 226-281 of Chess Treasury of the Air by Terence Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966). In the case of Alexander, it was his victory as Black over T.H. Tylor, Hastings, 4 January 1938.

(5650)

Björn Frithiof (Almhult, Sweden) asks about the game R. Fine v C.H.O’D. Alexander, Margate, 1937, which appears as follows in his database (ChessBase) and on pages 154-155 of Reuben Fine by A. Woodger (Jefferson, 2004): 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Qc2 Nc6 5 Nf3 d6 6 a3 Bxc3+ 7 Qxc3 O-O 8 b4 e5 9 dxe5 Ne4 10 Qe3 f5 11 Bb2 Nxe5 12 Nxe5 dxe5 13 g3 Be6 14 f3 Nd6 15 Qxe5 Qe7 16 e3 Qf7 17 c5 Nc4 18 Bxc4 Bxc4 19 Kf2 Bb3 20 Bd4 Rae8 21 Qf4 Bd5 22 Be5 Bxf3 23 Bxg7 Bxh1 24 Bxf8 Rxf8 25 Rxh1 Qa2+ 26 Kf1 Qxa3 27 Kg2 Qb2+ 28 Kh3 Qe2 29 Rf1 Qg4+ 30 Kg2 Re8

31 Qxf5 Qxb4

32 Rf4 Qd2+ 33 Kh3 Qxe3 34 Qd7 Qe7 Drawn.

Our correspondent comments:

‘What puzzles me is the conclusion of the game, after 31...Qxb4. White is said to have played 32 Rf4 (instead 32 Qf7+, which wins at once), and after the further moves 32...Qd2+ 33 Kh3 Qxe3, White had an immediate win with 34 Rg4+.’

We believe that White’s 31st move was mistranscribed as Qxf5 instead of Qxc7, i.e. QxKBP rather than QxQBP. The move was given as 31 QxQBP on page 304 of the June 1937 BCM and on pages 51-52 of The best games of C.H.O’D. Alexander by Harry Golombek and Bill Hartston (Oxford, 1976).

(6112)

In the Preface to the first volume of Chess Characters, G.H. Diggle explained his nom de plume:

‘In 1949 the writer created a record in London Banks League Chess by losing a game in seven moves (for details see article 49). Later he sent the score on a Christmas Card to the late C.H.O’D. Alexander who, with a flash of genius, sent a card in return awarding him the title of “Badmaster”.’

Alexander also described Diggle as ‘one of the best writers on chess that I know’ on page 138 of A Book of Chess (London, 1973).

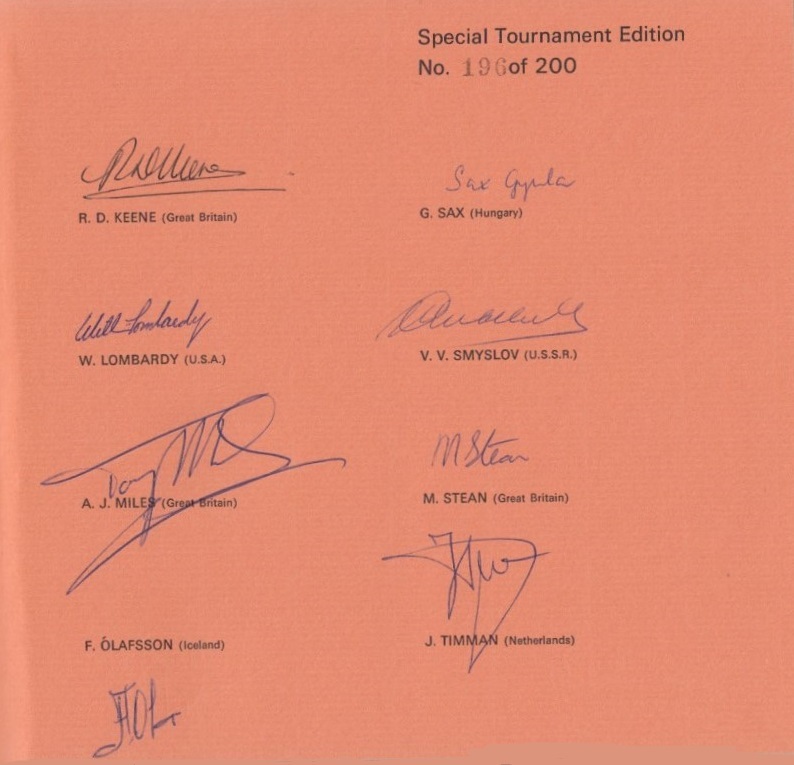

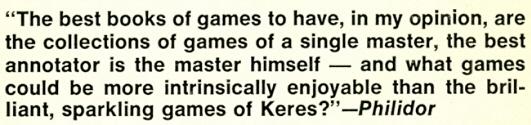

Paul Keres

Chris Eve (Victoria, BC, Canada) mentions a citation on the back cover of Grandmaster of Chess The Complete Games of Paul Keres by P. Keres (New York, 1972):

We note that clarification of the ‘anachronism’ is supplied by the back cover of the original edition (London, 1969) of the third volume in the series:

The full text of the Spectator article by ‘Philidor’ would be appreciated.

(6210)

From Leonard Barden:

‘“Philidor” was C.H.O’D. Alexander. The Sunday Times, where he wrote under his own name, objected to him writing what it considered a rival column; hence the pseudonym.’

(6215)

Many entries in the 2004 volumes of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography conclude with a reference to ‘wealth at death’. We note, in particular, the following:

(6418)

C.H.O’D. Alexander

The famous short story ‘The Thinking Machine’ by Jacques Futrelle (1875-1912) was mentioned by P.W. Sergeant in the first paragraph of his article on Deschapelles on pages 117-119 of the April 1916 BCM:

‘Some years ago the late Jacques Futrelle, who was one of the Titanic victims, wrote a book called The Thinking Machine on the Case, describing certain exploits of a “famous scientist” who out-Sherlocks Sherlock Holmes in the detection of mysteries. In one of the stories in the series we read how the Professor after one hour’s instruction in the game of chess, hitherto unknown to him, defeats the Emmanuel [sic] Lasker of his day, using his logical faculty to supply the place of experience in the game. Now Jacques Futrelle, it need hardly be said, was no chessplayer. But there was a chessplayer flourishing a century ago who apparently asked the world to believe about him the same marvel as Futrelle puts before us in the imaginary case of The Thinking Machine. And this player was no other than Deschapelles.’

A website dedicated to Futrelle has the full text of the short story, and below we reproduce from page 7 of his anthology The Professor on the Case (the title of the British edition of The Thinking Machine on the Case) a passage which has intrigued chess enthusiasts:

Alain C. White discussed Futrelle in his article ‘Chess in Detective Stories’ on pages 305-309 of the August 1911 BCM, and regarding the game which Professor Van Dusen (having only just been introduced to chess by Hillsbury) won against the champion Tschaikowsky, A.C. White wrote:

‘It must have been a remarkable game, though; and anyone who could reconstruct it from the graphic description would confer a lasting favour on lovers of “brilliants”.’

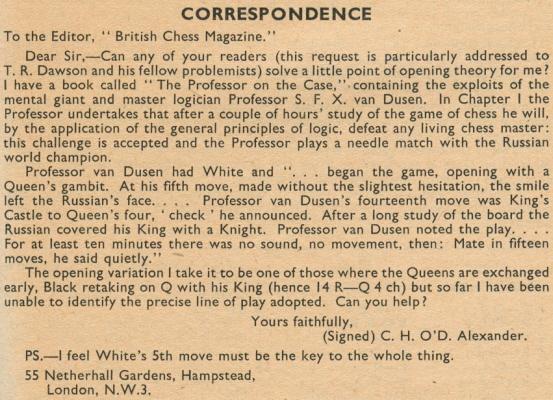

Decades later another eminent figure raised the reconstruction question. From page 205 of the June 1948 BCM:

It needs to be considered whether 14 Rd4+ could be a discovered check.

(6652)

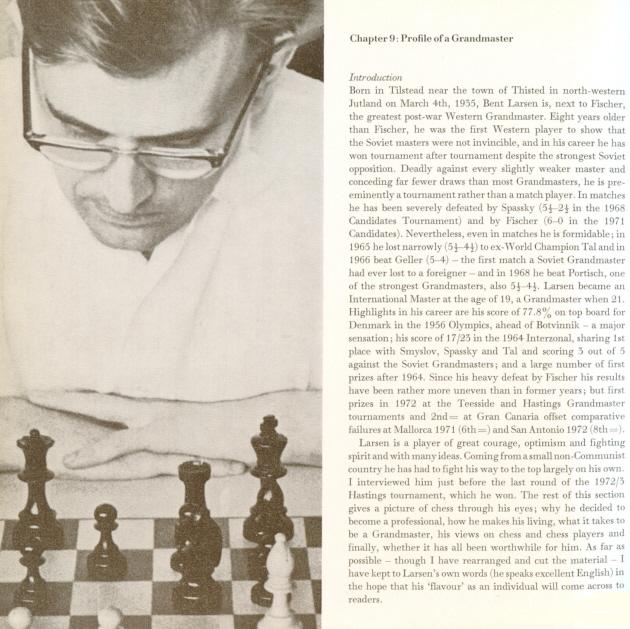

The best and most detailed interview with Bent Larsen that we have seen was presented by C.H.O’D. Alexander on pages 86-94 of A Book of Chess (London, 1973) under the heading ‘Profile of a Grandmaster’. It took place shortly before the last round of Hastings, 1972-73.

(6764)

For extracts from the interview, see our feature article on Larsen.

This photograph of James Whitfield Ellison comes from the dust-jacket of his chess novel Master Prim (London, 1968).

Pages 189-198 included a 29-move game between Julian Prim and Eugene Berlin, and that part of the story was reproduced on pages 143-146 of A Book of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1973). Alexander did not identify the game, which was Alekhine v Sterk, Budapest, 1921.

C.N. 2830 (see pages 2-3 of Chess Facts and Fables) discussed that brilliancy prize game, noting that Alekhine’s first volume of Best Games contracted it by one move.

(6934)

See Chess in Fiction.

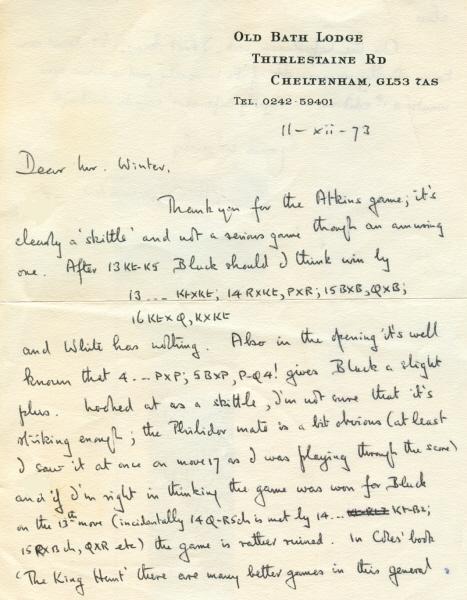

On 11 December 1973, a couple of months before he died, C.H.O’D. Alexander wrote us a letter about the Danish Gambit game:

By ‘Coles’, of course, Cozens was meant. See too in this connection page 587 of the December 1979 BCM, which also referred to Chernev and his ‘psychic phenomenon’.

(7096)

Details are given in our feature article on Franklin Knowles Young.

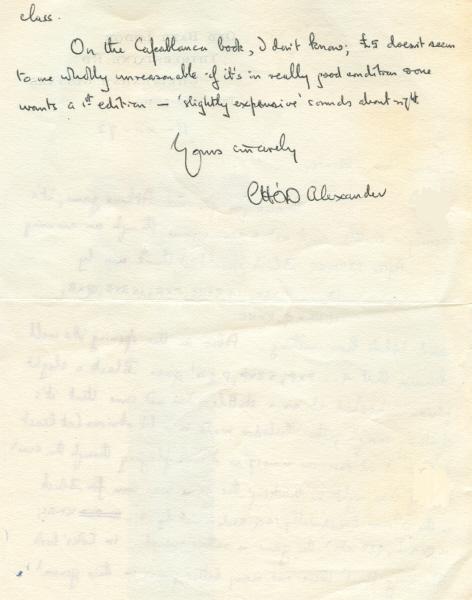

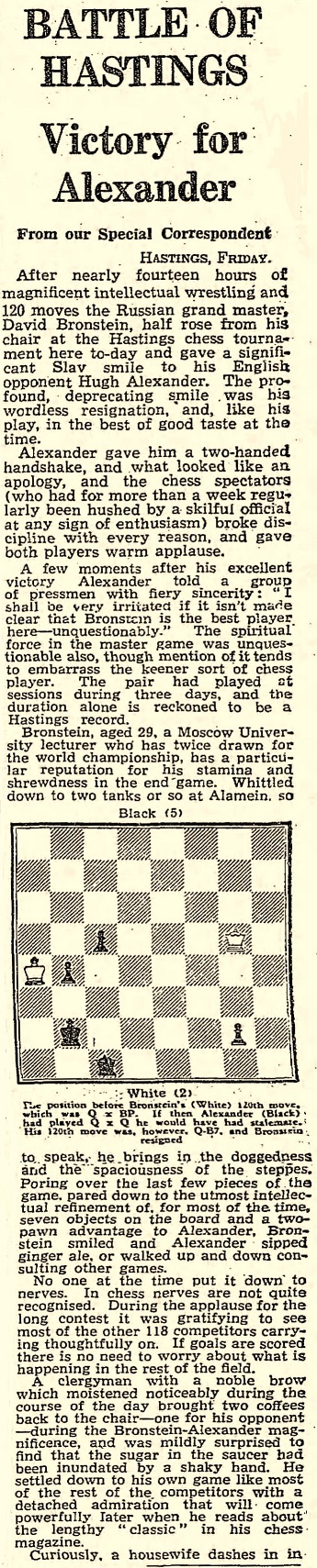

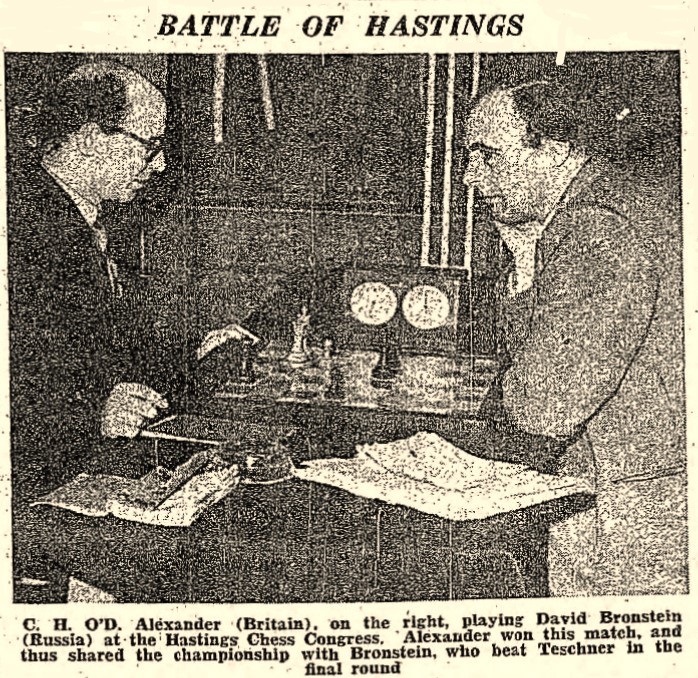

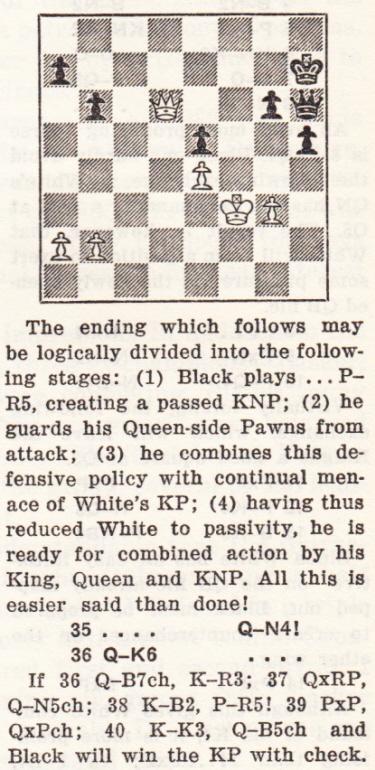

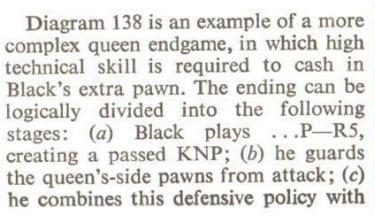

The front of the dust-jacket of the original 1954 edition of Fred Reinfeld’s book How to Play Chess, with a shot of the famous game in which Alexander defeated Bronstein at Hastings:

(7569)

The result was front-page news in the Manchester Guardian, 9 January 1954, as shown below, with, on page 10, a photograph in addition to further coverage:

A photograph submitted by Olimpiu G. Urcan:

(Illustrated London News, 16 January 1954, page 93

(9020)

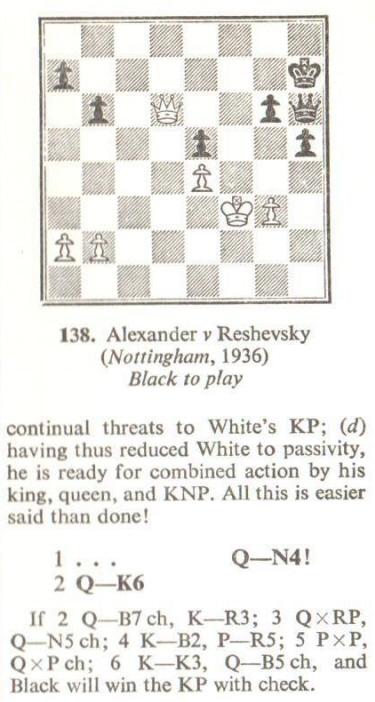

Peter Morris (Kallista, Australia) draws attention to two books which discuss Alexander v Reshevsky, Nottingham, 1936:

Page 80 of Reshevsky on Chess by S. Reshevsky (New York, 1948)

Page 84 of How to Play the Endgame in Chess by L. Barden (London and Glasgow, 1975)

We have raised the matter with Leonard Barden, who responds:

‘The great majority of my writing was and is solely by me, but I had a collaborator for the Collins book who wrote some chapters and supplied some material, though I personally checked the whole book in proof.

At nearly 40 years’ distance I cannot recall or decide which of us was responsible for Alexander-Reshevsky. In either case I would have expected at least some rephrasing, as occurs in the other notes quoted, so I now think that the neglect to do this was simple human error.

I should add that I find it completely convincing that Reinfeld wrote the Reshevsky book and thus the paragraph in question. When Reshevsky really wrote his own notes, as he did in some late material in Chess Life, the style was terse and arid, in contrast to Reinfeld’s lucid and informative explanations.’

See too Chess and Ghostwriting.

C.N. 8431 asked whether many instructional works had explained the knight’s move by reference to squares inaccessible to the queen, as did Learn Chess Fast! by S. Reshevsky and F. Reinfeld.

Trevor Moore (Baughurst, England) draws attention to Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1937), as well as the expanded, updated edition, Alexander on Chess (London, 1974). From pages 4-5 of both books:

‘Like the other pieces it [the knight] moves in a straight line, but one less clearly indicated on the board than those of the rook and bishop. The rook moves parallel to the edges of the board, the bishops diagonally and the knight in a direction bisecting the angle between the rook’s and bishop’s move. ... The knight’s move is complementary to that of the queen, as we may easily see in the following way. Place the queen on one of the 16 central squares of the board – it controls 16 of the 24 squares surrounding it. Now place a knight on the square instead – it controls precisely those eight squares not attacked by the queen. ... It is often inaccurately said that the knight “jumps” other pieces – actually, it simply moves between them.’

(8465)

Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander was warmly praised by both the BCM and CHESS when it first appeared. On page 7 of the January 1938 BCM ‘G.S.A.W.’ (Wheatcroft) commented:

‘It is a pleasure to find an expert player who can expound the essentials of the game as clearly with his pen as with his pieces.’

From page 155 of CHESS, 14 January 1938:

The book went through many editions, all published by Pitman, as was, posthumously, Alexander on Chess. The original edition was also brought out by David McKay Company, Philadelphia in 1938, and in a brief notice on page 218 of Chess Review, September 1938 ‘F.R.’ (Reinfeld) wrote:

‘Alexander is a teacher, and if this book is any indication, he must be a good one. Chess will undoubtedly become the most popular introductory book to the game. It is written with exceptional clearness, and covers so much ground that it will be found useful by those who are by no means mere beginners.’

(8466)

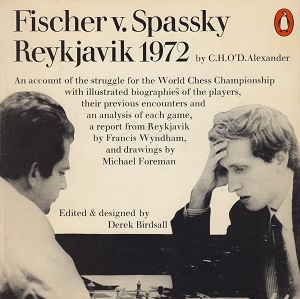

Among the ploys available to a chess writer eager to be quoted is recourse to inapposite, exaggerated comparisons, similes and metaphors which offer the apparent thrill of mentioning names not normally seen in chess literature. The stratagem is not new, and even a fine author may succumb to the temptation. From page 25 of Fischer v. Spassky Reykjavik 1972 by C.H.O’D. Alexander (Harmondsworth, 1972):

‘However, while the conditions of the match are simple, the two-month match itself is a gladiatorial contest compared with which Joe Frazier v Muhammed Ali is just a friendly little chat.’

The line has indeed been cited elsewhere, and notably by Alexander himself on page 44 of A Book of Chess (London, 1973).

Other short-cuts to being quoted include bogus epigrams, extravagant historical comparisons, and hyperbolic praise or criticism of a given master’s play. For some reason, a foray into zoology can be particularly useful. The writer managing to work, say, ‘cobra’ into any description of a player or game may well find the phrase picked up by others.

(8606)

On page 88 of his book on the 1972 world championship match, Alexander wrote after 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 c5 in the third game:

‘Just as 3...P-Q4 in Game 1 said “I am content to draw”, so this says equally clearly “I am playing to win”. The Benoni is a double-edged opening, in which Black concedes White a central pawn majority in return for a queen’s-side pawn majority of his own. Both sides also have considerable tactical scope. On the whole, I think that if God played the Benoni against God, White would win – but at the human, even world championship, level, practical chances are about equal. The former world champion, Mikhail Tal, did a lot to popularize the defence; a brilliant attacking player, he showed how many tactical resources the Benoni contained.’

On pages 156-157 of their Alexander monograph, Golombek and Hartston commented in the notes to V. Nevole v Alexander, International Correspondence Chess Olympiad Preliminaries, 1968-70, after 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 c5 3 d5 e6 4 Nc3 exd5 5 cxd5 d6:

‘The fighting spirit of this defence very much appealed to Alexander, though he was not totally convinced in its positional correctness. In his own words: “If God played God in the Benoni, I think that White would win; at lower levels, however, Black has excellent practical chances.’

From page 18 of A Book of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1973):

‘Fifteen to 20 years ago I published an account of a Korean [sic] boy, Ernest Kim; this drew a letter in which the writer said that, travelling along the “Golden Road to Samarkand”, he had stopped overnight at Tashkent. He admitted to playing a little chess and was at once pressed by the locals to play “our champion”; he reluctantly agreed – and a tiny four-year-old was brought in. It was Kim. But now he must be about 20 – and I have never seen his name as an adult player.’

From Alexander’s writings we can quote only two other brief references to Kim:

‘A new chess prodigy has appeared who makes Bobby Fischer appear senile. Ernest Kim has won the championship of Tashkent at the age of five; however, he is not yet of master strength – only about average British championship standard.’

Source: Sunday Times, magazine section, 15 February 1959, page 26.

Secondly, ‘Ernest Kim, the five-year-old champion of Tashkent’ was referred to by Alexander on page 28 of the Sunday Times, magazine section, 5 April 1959.

(8884)

See also Chess Prodigies.

From page 14 of A Book of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1973):

‘Overall, chessplayers are much less odd than is generally supposed. It is unfortunate that Fischer is such an extreme type; his unbalanced behaviour has inevitably encouraged journalistic muck-raking for other eccentricities amongst chess masters. I find the references to Steinitz and his statement that he could give God odds at chess particularly repugnant; Steinitz’s mind broke down when he was old, ill, unhappy and within a year of his death. It is as misleading as it is heartless to represent his conduct then as if it were his normal behaviour.’

(8920)

See Steinitz versus God.

From page 15 of A Book of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1973):

‘... all attempts – I am happy to say – to show that chessplayers have some unique mental faculty (e.g. exceptional memory) have been unsuccessful; the only respects in which they are superior to non-chessplayers of the same general calibre seem to be those in which their experience of chess is directly relevant.

Summing up, can we form any kind of composite picture of a chessplayer? He is likely to be an individualist with a good deal of aggression in his make-up, better with things than with people, mathematically oriented and at home with abstractions, and an opportunist; in his feeling for positions he has something of the artist in him, he has some creative power but on a small scale – he is a miniaturist, better at detail than at large-scale ideas. He is no crazier than anyone else – but when he is crazy, he will probably be paranoiac. But – as is shown by the millions of players in the USSR – there are potentially many of him; given suitable soil, caissa vulgaris is a common enough growth.’

(9283)

An advertisement from the back cover of the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, December 1947:

C.H.O’D. Alexander’s book was published nearly two years later, the dates in the title being 1938-1945. No material by Francisco Lupi was included, and we wonder whether the intention had been to give a new text by him or merely to reproduce the articles which, as discussed in C.N. 4388, he published shortly after Alekhine died.

(9888)

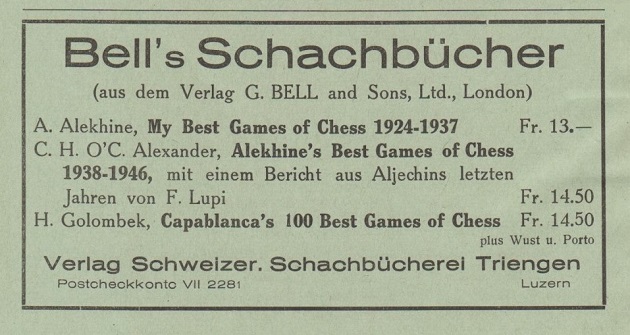

Black to move

C.N. 9903 asked which annotator gave ...Qe2 mate in both the above positions.

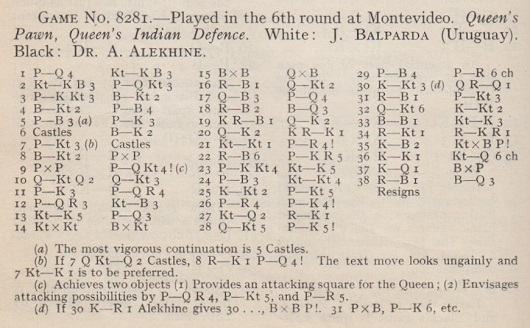

The answer is C.H.O’D. Alexander, in his annotations to Balparda v Alekhine, Montevideo, 1938 on pages 15-17 of Alekhine’s Best Games of Chess 1938-1945 (London, 1949):

The mistake was pointed out in a review on page 5 of the October 1949 CHESS, and the note was amended in subsequent editions:

The full score of the Balparda v Alekhine game, which was played in the sixth round of the Montevideo tournament on 14 March 1938: 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 b6 3 g3 Bb7 4 Bg2 c5 5 c3 e6 6 O-O Be7 7 b3 O-O 8 Bb2 cxd4 9 cxd4 b5 10 Nbd2 Qb6 11 e3 a5 12 a3 Nc6 13 Ne5 d6 14 Nxc6 Bxc6 15 Bxc6 Qxc6 16 Rc1 Qb7 17 Qf3 d5 18 Rc2 Bd6 19 Rfc1 Qe7 20 Qe2 Rfb8 21 Nb1 h5 22 Rc6 h4 23 g4 Ne4 24 f3 Ng5 25 Kg2 b4 26 a4 e5 27 Nd2 Re8 28 Qb5 e4 29 f4 h3+ 30 Kg3 Rad8 31 Rf1 g6 32 Qb6 Kg7 33 Bc1 Ne6 34 Rg1 Rh8 35 Kf2 Nxf4 36 Ke1 Nd3+ 37 Kd1 Bxh2 38 Rf1 Bd6 39 White resigns.

The game was published on page 280 of the June 1938 BCM:

We do not know whether the reference to ‘Alekhine gives ...’ in note (d) is based on a written or an oral comment.

The game was annotated by, among others, Santasiere, on page 54 of the May-June 1938 American Chess Bulletin. Showing its customary deep research, the Skinner/Verhoeven book on Alekhine recorded on page 623 that the game had been published in 1938 issues of El Ajedrez Americano, Xadrez Brasileiro and De Schaakwereld. All three gave annotations, and we are grateful to the Royal Library in the Hague for copies of the Brazilian and Dutch periodicals ...

(9916)

From C.H.O’D. Alexander’s column in the Sunday Times Magazine, 6 September 1970, page 38:

‘If you want to know what chess is about – or at least one of the things that it is about – you still can’t do better than read those magic books of the Twenties [sic] by Richard Réti: Modern Ideas in Chess and Masters of the Chess Board (published by G. Bell).’

The article concluded:

‘... when you have read Réti you will find that you have had your chess horizons widened without noticing it and you will be able, at least partially, to see the modern masters through Réti’s eyes.’

(10064)

Further to Where Did They Live?, Neil Blackburn (Redditch, England) notes that there are many postal addresses in a chapter entitled ‘Die Schachfreunde in Deutschland, Holland u. Oesterreich-Ungarn 1905/1906’ on pages 513-579 of the Barmen, 1905 tournament book. Additions to the feature article will be made in due course.

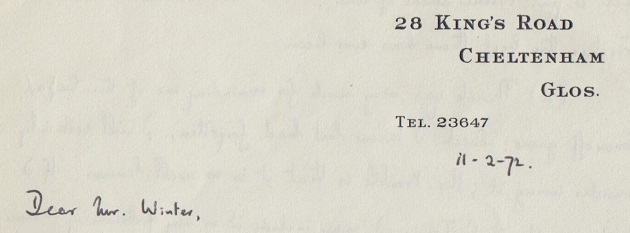

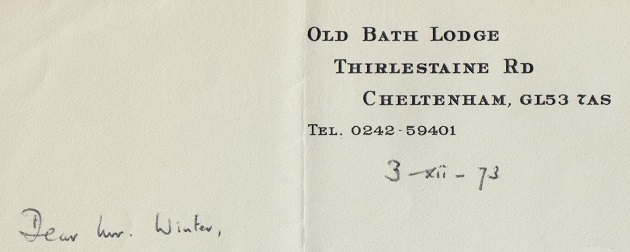

The article currently has no entry for C.H.O’D. Alexander, and Paul Lonergan (London) asks whether a Cheltenham address is available for him.

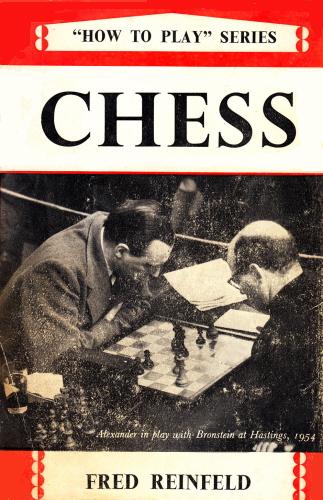

Many editions of the British Chess Federation Year Book of the 1950s and 60s gave Alexander’s address as Brecken Lane, Cheltenham. Towards the end of the 1960s there was a change to 28 King’s Road, and later Alexander’s address was the Old Bath Lodge, Thirlestaine Road.

The headings to two letters received from Alexander:

(10817)

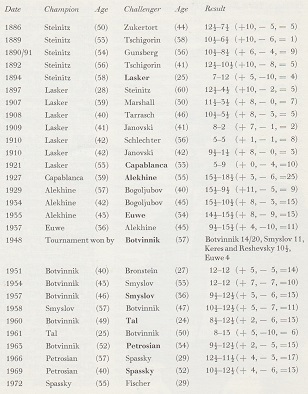

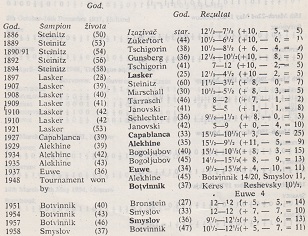

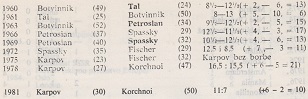

Alan O’Brien (Mitcham, England) points out that the chart of world title match results shown in Copying (C.N. 6617) was lifted by Dimitrije Bjelica from a book by C.H.O’D. Alexander:

Fischer v. Spassky Reykjavik 1972 by C.H.O’D. Alexander (Harmondsworth, 1972), page 21

Kasparov protiv Karpova by D. Bjelica (Sarajevo, 1984), pages 234-235

(10946)

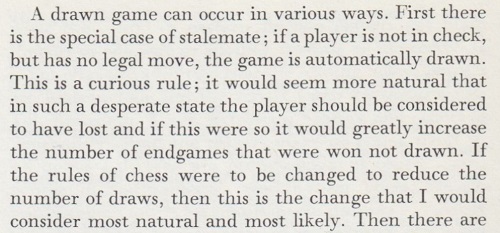

C.H.O’D. Alexander wrote on page 10 of Fischer v. Spassky Reykjavik 1972 (Harmondsworth, 1972):

In a letter on page 160 of CHESS, March 1973 T.D. Harding disagreed. Paul V. Byway disagreed with him on page 230 of the May 1973 issue, and Alexander wrote on page 258 of the June 1973 edition:

C.N. 7051 showed an account by Paul H. Litwinsky (later Paul H. Little) of an ‘offhand remark’ by Capablanca during the Nottingham, 1936 tournament:

‘He proposed to abolish the stalemate rule, saying that it was illogical.

His point was that often a player has a material superiority, such as two knights against a solitary king, or rook’s pawn and king against king, and yet is unable to win because of the stalemate. Capablanca’s suggestion was to give to the player with the material superiority two-thirds or three-quarters of a point ...’

(10984)

See Stalemate.

‘The lower the level of play, the less it matters what opening is chosen ...’

C.H.O’D. Alexander, BCM, July 1955, page 216.

(11005)

‘Some of Marshall’s most sparkling moves look at first like typographical errors.’

This well-known remark is listed in The Chess Wit and Wisdom of W.E. Napier. On page 194 of Great Brilliancy Prize Games of the Chess Masters (New York, 1961) Fred Reinfeld wrote:

‘Some of Alekhine’s best combinations are so startlingly original that they give the impression of being oversights. In this regard, 20 P-K4! is one of his most striking moves.’

The game was Alekhine v Alexander, Nottingham, 1936:

On page 196 Reinfeld commented regarding 20 e4:

‘This sly move looks like a blunder, as Black can now win a pawn.’

The game continued 20...Nxe4 21 Qc1 Nef6 22 Bxf5, and Black resigned at move 27.

(11177)

A passage by C.H.O’D. Alexander on pages 21-22 of Chess Treasury of the Air by Terence Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966):

(11198)

An observation by C.H.O’D. Alexander in his Foreword (page 5) to Chess Problems: Introduction to an Art by Michael Lipton, R.C.O. Matthews and John M. Rice (London, 1963):

‘The player comes to problems with the advantage of knowing thoroughly the language of chess, but with the disadvantage of being accustomed to a quite different use of this language. It is as if having read books solely for the sake of the information contained, one started to read poetry – entirely different things are now significant.’

(11346)

Stefan Müllenbruck (Trier, Germany) sends a column relevant to two topics discussed in C.N.: the player who claimed never to have beaten a healthy opponent (pages 322-323 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves and C.N. 4189) and the ‘When I am White, ... when I am Black ...’ remark (C.N.s 5063, 9647 and 10407). Both observations were ascribed to Emanuel Lasker in a column by ‘Philidor’ (C.H.O’D. Alexander) on page 866 of The Spectator, 22 June 1956:

(11510)

Mentioning C.H.O’D. Alexander’s ‘fascinating’ A Book of Chess on page 4 of the Saturday Magazine of the Birmingham Post, 10 November 1973, Peter Gibbs wrote:

‘The first chapter of the book gives the finest dissertation I have read on whether the game is an art or science.’

(12069)

Addition on 17 January 2025:

Reproduced with permission from the Hulton Archive, the above informal shot of C.H.O’D. Alexander and V. Smyslov was taken at the Caxton Hall, London on 3 July 1954. A two-round Anglo-Soviet match took place on 3 and 5 July.

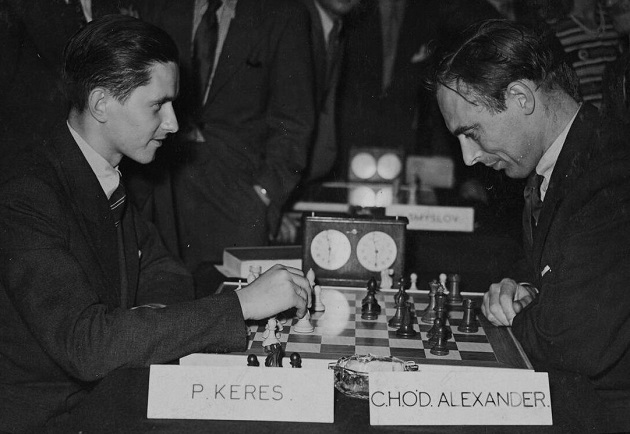

This photograph of Paul Keres and C.H.O’D. Alexander is reproduced courtesy of the Hulton Archive. It was taken during Hastings, 1954-55, but the board position is unrelated to their game in the tournament.

(12090)

From the front cover of the October 1966 issue of CHESS:

The unnamed author was P.H. Clarke.

Concerning the observation by C.H.O’D. Alexander – ‘It passes one of the best tests of a well-annotated book: the winner’s moves are quite frequently criticised’ – that full review is sought. The words were not in the chess column on page 39 of the Sunday Times Magazine, 7 May 1961, where Alexander compared the Clarke book favourably to Selected Games of Mikhail Tal by J. Hajtun (London, 1961).

(12154)

See too Chess Annotations.

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.