Edward Winter

A miscellany of Chess Notes items on how chess games have been annotated.

***

‘I quote this passage [from the Munich, 1900 tournament book] with particular pleasure, not only for the sentiments expressed, but also in order to acquaint present-day players with the racy diction of the inimitable Georg Marco. It may give them an idea of how much they lose by notes in the ever-encroaching Informator style, through which the greatest entertainment ever invented is reduced to a series of mathematical symbols.’

Source: W. Heidenfeld, Draw! (London, 1982), page 21.

(394)

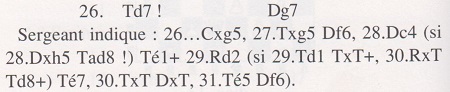

Znosko-Borovsky’s remark on 7...b5 in the game Capablanca-Reshevsky, Nottingham, 1936:

‘A somewhat risky continuation, but it appears quite safe.’

Source: BCM, October 1936, page 486.

(401)

To the end Alekhine remained a remarkably fine chess writer and claimed that Gran Ajedrez contained some of his best analysis. However, his wartime Spanish works are not without their defects; apart from an incredibly high number of misprints (for which, presumably, Alekhine was not to blame), the world champion himself became careless. Those who have 107 Great Chess Battles may wish to note the following:

Page 2: Note to Black’s 21st move, fourth line. Alekhine missed the mate in four, writing on page 113 of Gran Ajedrez ‘mate en cinco’.

Page 71: After Black’s 5th move. The English book omits a nonsensical note by Alekhine: ‘If 5...CD3A, White could avoid the exchange of his AR by playing 6 D2R P4TD 7 CR3A A3T 8 P4AD! etc.’ (Gran Ajedrez, page 145).

Page 111: After 1 P4R P4AD 2 P3AD P4D 3 PxP DxP 4 P4D C3AD 5 C3AR A5CR 6 A2R PxP 7 PxP P3R 8 C3AD A5CD, Alekhine in fact added to the given note that a better course would be 8...C3AR 9 O-O D4TD etc. This, of course, is impossible. (Ajedrez Hipermoderno, volume II, page 12).

Page 221: Note to White’s 35th move. Alekhine actually wrote ‘38 R4A C6R+ 39 R5A, followed by 40 R6A etc.’ The last-mentioned move is illegal and suggests that Alekhine was indulging in blindfold analysis.

Spanish notation works as the English descriptive. R=king; D=queen; T=rook: A=bishop; C=knight; P=pawn. Thus the QP, Nimzowitsch Defence begins: 1 P4D C3AR 2 P4AD P3R 3 C3AD A5C.

(687)

Of all the traps confronting the chess writer that of ‘annotating by result’ is one of the most formidable. So often it is implied that the winner did not put a foot wrong, while the opponent was doomed from the start. Agonía de un Genio by Pablo Morán has a curious example. On page 278 is the game Alekhine-Gallego, Gijón, 1944, which began: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O b5 6 Bb3 Be7 7 d4. This last move is awarded an exclamation mark, and there is a note saying that White takes advantage of Black’s divergence from the usual order of moves by playing d4 straight away without losing time with Re1. However, the same position crops up on page 294, except this time Alekhine is Black (against Medina, Sabadell, 1945). But now White’s 7 d4 is criticized, 7 a4 being recommended. (In fact, although he won against Gallego, Alekhine only drew with Medina.)

(704)

An Endnote on pages 265-266 of Chess Explorations:

The discrepancy remained in the subsequent English edition, A. Alekhine, Agony of a Chess Genius (Jefferson, 1989). See pages 216 and 227 of that book.

‘Annotations attempt to prove that a game had only one logical sequence.’ (J.J. Walsh.) See C.N. 775 in Chess Jottings.

Alekhine’s comment on Sämisch-Navarro, Madrid, 1943:

‘Sämisch wanted to show in his last game of the tournament that he is capable of playing a game without running out of time.’

Source: tournament book, page 212.

(784)

A couple more examples of side-swipes by Alekhine at fellow masters:

Fine-Capablanca (Nottingham, 1936 tournament book, page 244) – drawn in 20 moves: ‘A delightful game for the annotator. I think it is the only one in this collection which does not even deserve a diagram.’ (It wasn’t.)

Euwe-Flohr (Zurich, 1934 tournament book, page 133) – drawn in 19 moves: ‘A typical Euwe-Flohr game!’

(947)

In Great American Chess-Players, II H.N. Pillsbury by P. Wenman (London, 1948), the final comment to a consultation game on pages 106-107 is:

‘A chessy game of great interest all through.’

From page 56 of the June 1984 Chess Life there is this gem from Robert M. Snyder following 1 e4 e5 2 Nc3:

‘So far the game has proceeded along the normal lines of the Vienna Game.’

(755)

C.N. 755 quoted a profundity by Robert M. Snyder. Here is another, from the May 1984 Chess Life (page 36):

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 f6? ‘All has been normal up to here.’

(789)

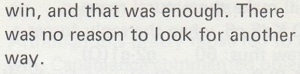

We do believe that game annotations, including !s and ?s, should tell a coherent story of mistakes and their exploitation – unless the writer admits that he does not know what is going on. The thought comes to mind after recent perusal of Fine’s (mediocre) book Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World Chess Championship. Games 5 and 6 of the 1972 match will suffice as examples. Spassky is alleged to have made a string of bad moves, yet somehow he still has a draw available many moves later.

(857)

For the remainder of C.N. 857, concerning other aspects of the book, see Reuben Fine, Chess and Psychology.

Below is part of a contribution in 1985 by John Nunn (London) to C.N. 993:

‘When I was younger, my games were occasionally annotated in magazines by other players. I was astonished to see what they wrote; indeed, on some occasions, I could scarcely believe that it was the same game. When I started annotating games myself I began to see how difficult it is to write about other players’ games. Of course, one can restrict oneself to essentially trivial comments, or fall back on the usual clichés, but really to penetrate the reasoning of another player is very hard. It is correspondingly valuable when one does gain a fresh insight by analysing games, but this requires a great deal of time which is not always available.’

The Test of Time by G. Kasparov, translated by K.P. Neat (Pergamon Press) ... turns out to be a top-notch book, fully worthy of a world champion. It is rare indeed for everything (games, annotations, translation, production) to come right in a single book but The Test of Time is definitely that exceptional work. The apparent innovation of giving annotational second thoughts in a clearly distinguishable way deserves to be copied, but will it be? Such a search for chess truth makes great demands on the annotator.

... The depth and beauty of Kasparov’s writing in The Test of Time may be contrasted with the way others write up his games. One instance will suffice: On page 101 of the July 1985 CHESS (Kasparov-Hübner, second match-game) the latter’s 14th move is criticized, apparently on the basis of what Raymond Keene wrote of 14...Qd8 in The Spectator of 15 June 1985: ‘An inexplicable retreat. Why not 14...a5 at once?’ However, Kasparov subsequently annotated the game in the August 1985 New In Chess. He dismissed 14...a5 because of 15 bxa5 Rxa5 16 Rxb6, and called 14...Qd8! ‘an excellent positional idea’. Kasparov said that Black’s fatal errors were his 27th and 30th moves. Both of these are passed over without comment by CHESS and The Spectator. And did the passion for truth lead those two magazines to print corrections? Of course not.

(1145)

Another example of B.H. Wood’s increasingly peculiar judgement, from a letter to us dated 11 September 1986:

‘I just noticed C.N. 1145. I certainly would never claim 100% accuracy over any annotation even one by Kasparov however high a percentage he would attain. He even committed one inaccuracy in an earlier world championship game which was noticed with surprise by practically 95% of the spectators.’

What precisely is Mr Wood saying? Does he mean that he examined and rejected Kasparov’s view on that Hübner move? If so, why didn’t readers deserve to be told Mr Wood’s reasons, or at least be informed that Kasparov’s opinion differed from that of CHESS? Did he overlook the Kasparov note in New in Chess? Or did he simply not want to give publicity to a Dutch rival magazine of such marked superiority?

Mr Wood’s statement ‘I certainly would never claim 100% accuracy over any annotation’ is plainly untrue. As recently as in the June 1986 issue of CHESS (page 128) there was the following editorial comment:

‘If you find any move hard to understand, STOP and investigate. It will not be an error: this analysis is of top quality.’

(1282)

The 3/1987 issue of New in Chess (pages 5-6) published an exchange of correspondence between Kasparov and Karpov. A general argument expressed by the former deserves unreserved support:

‘I also think that it is a chessplayer’s duty to update his older analyses and notes from time to time. This is necessary as it should not be permitted in any manner that the text or analyses contain obvious technical anachronisms or mistakes, as a consequence of the rapid development of theory and practice. Moreover, a reprint or a revised edition of a book can and should reflect the changes in the author’s chess ideology caused by his experience over the years. Neglecting these factors in my view reduces the significance of such books and curbs the development of chess.’

(1391)

C.N. 27 referred to ‘one of those rare games in which everything is so orderly and logical that for many players annotations would be superfluous’. [The game was Capablanca v Romi(h), Paris, 11 January 1938.] A writer who took this approach to extremes was Weaver B. Adams, in his introduction to How to Play Chess:

‘A word with regard to the games which follow: there are no annotations, because I feel that they are not necessary. Each move is crystal clear. No other move could possibly be played in the position. This is what happens in a game when you get the right start. Essentially chess is not difficult. It is only because of the popularity of certain openings that we get an opposite impression. But by applying the principles, (1) maximum increment of power afforded to the piece moved, (2) maximum mobility (usefulness of the square vacated), (3) minimum loss of option (don’t move a piece until it is certain where it is best posted), and (4) minimum weaknesses (check all weaknesses to see if they can be tolerated), seldom will it not be clear that but one move satisfies all of these conditions.’

(1612)

Some mordant comments by Purdy from page 89 of the July-August-September 1966 Chess World:

‘The worst annotator of all time was Tinsley, who used to edit the chess column of the London Times Weekly [sic] in my boyhood and quite a long time after that. His father was S. Tinsley (an expert who played at Hastings, 1895), and when the father died, the son came along with copy as usual. The management (not chessplayers) took him on, and paid him good money for gibberish over several decades till at long last he died, regretted by none of the many chess-playing readers of the Times in the far-flung outposts of the Empire.

He earned the curses of the chess world, and many players would have reserved him a special corner of Hell where he could receive his weekly cheques as usual but never cash them through all eternity.’

(2742)

‘We do not approve of dry, completely objective annotations – this move is correct, this superior, this inferior, etc. An annotator should try rather to enter into the mind of the player, and explain his ideas.’

Source: Chess World, 1 March 1946, page 33.

(10382)

C.N. 434 quoted the following from page 148 of C.J.S. Purdy, His Life, His Games and His Writings by J. Hammond and R. Jamieson (Melbourne, 1982):

‘We fear that students often get wrong impressions because writers use condemnatory words about errors that are really extremely slight.’

An extract from C.N. 1966:

In March 1993 Caissa Editions brought out Paul Morphy and the Evolution of Chess Theory by Macon Shibut. In a sense, it complements David Lawson’s extensive biography of 1976, which paid little attention to Morphy’s games. An underlying argument in Macon Shibut’s book is that they have seldom been accorded sufficient analytical attention, and he puts his case well (page 8):

‘Annotators who want to educate or entertain are not interested in tearing apart an instructive Morphy combination. Rather, they want to find characteristic errors in the opponents’ play, and they want the hero’s consequent victory to seem a matter of course (and the more elegantly achieved, the better). The effect of such presentations in countless beginner’s texts has been to reduce Morphy’s games to a collection of fables.’

In London on 17 February 1993 Kasparov gave a simultaneous exhibition against consulting groups. The most widely published game, a victory for him as White over a team which included Maxim Dlugy, began 1 d4 d5 2 c4 dxc4 3 e4 b5 4 a4 c6 5 b3 e5 6 axb5 cxb5.

Numerous commentators described the line (and 5...e5 in particular) as a theoretical novelty, yet it has long been known, having appeared on page 829 of the 1922 edition, revised by Schlechter, of Bilguer’s Handbuch des Schachspiels. The only difference is the inversion of moves 5 and 6 by both sides.

‘If it’s not in ECO or my database, it must be a theoretical novelty’ is dangerously slack reasoning for an annotator.

(1975)

‘To annotate any game conscientiously it is necessary to accord it at least as much objective study as was expended by the players in the actual encounter.’

I. König, in his introduction to the book of the Nottingham, 1946 tournament (won by R.F. Combe).

(2422)

In C.N. 675 [see page 117 of Chess Explorations] a correspondent suggested that the longest ever set of annotations to a single game was Hübner’s notes on his loss to Portisch at Tilburg, 1981. But now comes a 202-page book devoted to a single game: Kasparov Against the World by G. Kasparov and D. King (New York, 2000), although there is also much diary material. On the final page Kasparov expresses the view that it is ‘one of the greatest games of chess ever played’.

(2483)

Emanuel Lasker had some harsh words for chess analysts in his New York Evening Post column of 15 March 1911, page 11, which was quoted on page 155 of the July 1911 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Games from San Sebastian continue to arrive. The majority of them are very fine. But the chess-press disfigures them by misleading notes. If the games had voice, they would cry out against the violence done them. They are bespoiled of their true beauty, and a pink and powder brilliance is forced upon them.’

(Kingpin, 1994)

The game below features A.E. Santasiere’s full set of annotations, from page 99 of the November-December 1943 American Chess Bulletin. It will be a stoic reader who manages to go through the notes without flinching, cringing or sniggering.

Edward Schuyler Jackson – Ariel Mengarini

New York, November 1943

Ruy López1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Bxc6 (‘This penny-pinching move has deservedly fallen out of favor.’) 4…dxc6 5 Nc3 Bc5 (‘An enterprising continuation, but 5…f6 is more promising.’) 6 d3 (‘Not 6 Nxe5 because of 6…Bxf2+ and 7…Qd4+.’) 6…Qe7 7 h3

(‘7…Bg4 need not at all have been prevented, since 8 Be3 is a good counter. In his choice of opening variation, and particularly in this ultra-cautious text, Jackson reveals his spiritual outlook for this game – fearfully conservative.

And he, especially, is always so brave, so fearless; it is the one quality in his play that has commanded our love. This only proves that when the moment is crucial enough, when it hits our tenderest desires, we become afraid! Of what? (We’ll be a long time dead and forgotten.)

Are we afraid of ourselves? (isn’t that silly?); or afraid for our little reputation? I know what it is, for I, too, have been afraid; in fact, my whole life has been a struggle against fear. And it is because I have come finally to realize true values, that I dare talk at all. Suffering either makes us or breaks us.

The Bible tells us “to lose ourselves”. Rousseau said he had never begun to live, until he had given up all hope of living! That, too, has been my experience. One can get away from our terribly important ego; one can let loose - and it makes for wonderful Godlike living.

Fear is part and parcel of vanity – dark, selfish, negative. It is worth any effort, any suffering to learn the true meaning of love in the highest (i.e., God, ideals), for then we are really free – really fearless; we depend not on ourselves, but on something (Universal – Spirit – Force) better and stronger than ourselves. In the cause of love and courage, we are even willing to die in the body. Then truly, do we deserve to live! Think for a moment of Lincoln, of Joan of Arc, of Jesus.’)

7…Nf6 8 O-O Bd7 9 Qe2 h6 (‘Preparing the following attack.’) 10 Be3 g5 11 Nh2 O-O-O 12 Bxc5 Qxc5 13 Qe3 Qb6 14 Na4 Qd4 15 Nf3 (‘A miscalculation which loses the game. After 15 Qxd4 exd4 16 Nc5, White would have at least an even game. Further comment is not necessary.’) 15…Qxa4 16 Qa7 Be6 17 Nxe5 Nd7 18 b3 Qb5 19 Nc4 a5 20 Nxa5 Qb6 21 Qa8+ Nb8 22 Nc4 Qa6 23 Qxa6 Nxa6 24 f4 gxf4 25 Rxf4 Rdg8 26 Kh2 Rg5 27 a3 Rhg8 28 Ne3 c5 29 g4 Nb8 30 Raf1 Nc6 31 R1f2 Nd4 32 b4 cxb4 33 axb4 Nc6 34 c3 Ne5 35 Rd2 h5 36 d4 Ng6 37 Rf6 hxg4 38 Rg2 Nh4 39 Rg3 Nf3+ 40 Kh1 Nd2 41 Rf4 gxh3 42 Rxg5 Rxg5 43 d5 Bd7 44 Rxf7 b5 45 Rf8+ Kb7 46 Rf4 Rg3 47 Nf1 Rf3 48 Rxf3 Nxf3 49 Ne3 Kc8 50 c4 bxc4 51 Nxc4 Bb5 52 Ne3 Kd8 53 e5 Nxe5 54 Kh2 Bd7 55 Kg3 Ke7 56 b5 Kd6 57 Kh2 Ng4+ 58 White resigns.

(2639)

Annotators and translators often lapse into Reverse English. C.N. 2972 gave an example (‘Undoubtedly more tenacious was 27…Ne5’) from page 292 of Kasparov’s first Predecessors volume.

In a wide-ranging letter about books on pages 58-59 of the December 1950 CHESS A.C. Simonson wrote:

‘I like to find instances where the annotators make mistakes. The armchair critics, as I like to term them, are always looking to criticize the players; in doing so, they very often make laughable mistakes themselves.’

And:

‘Incidentally, although I have discovered such errors in every single chess book, the prize seems to be captured by H. Golombek with his Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games, which contains – literally – hundreds of typographical, diagrammatic and annotation errors.’

On page 81 of the January 1951 issue Golombek made one of his rare contributions to CHESS:

‘... I should like to point out that this is quite untrue with regards to the English edition. To the best of my knowledge it contains only one misprint which, I think you will agree is well below the average for a book of its size and type.

However, it is true that the American edition contains many errors. This was due to the fact that the American publishers, by a stupid blunder on their part, failed to incorporate my galley proof corrections in the final proofs they sent to the printers. This was a circumstance over which neither my English publishers nor myself had any control as we were in no way responsible for the American printing.’

The CHESS Editor was unconvinced:

‘Mr Simonson gave some random examples of the errors and, whilst the misprints are admittedly almost absent from the English edition, his analytical criticisms do apply to it, seem well based and, for the first few games alone, with diagrams would fill a page of CHESS.’

As regards Golombek’s recognition of only one misprint in the English edition of his book, it may be recalled that in C.N. 3586 we provided an eight-page list of mistakes of all kinds. It would certainly have been far longer had it dealt with the US edition.

(3767)

See Harry Golombek’s Book on Capablanca.

From page 158 of CHESS, April 1940 (in a review of Reinfeld’s book Practical End-Game Play):

‘Mr Reinfeld is an attractive and industrious writer but there are certain faults of which he must rid himself to become a great one. It is in all kindness that we enumerate them. The first is bumptiousness. He is too prone to throw his weight about from the safe retreat of armchair analysis. The amateur reader, hearing him denounce Tarrasch for “gross blunders”, Schlechter for “superficial appraising of the position”, Euwe for “grossly miscalculating”, Tartakower for “lack of insight” and so forth can hardly fail to ask, with initial admiration: “Who is this genius who can pierce through the armour of the great?” Mr Reinfeld’s playing record comes as a shock. The discovery of occasional “gross errors” in his writings, committed not under the nervous tension of tournament play but in the calm of literary composition and overlooked in successive proof-corrections and the realization that the analysis on which he bases his denunciations is rarely his own (as his own meticulous acknowledgments reveal) add to the disillusionment. Such a disillusionment is unnecessary and pointless. We judge a writer as a writer, a player as a player – until the writer obtrudes his own personality on us by such harsh and pointless criticisms.’

(3829)

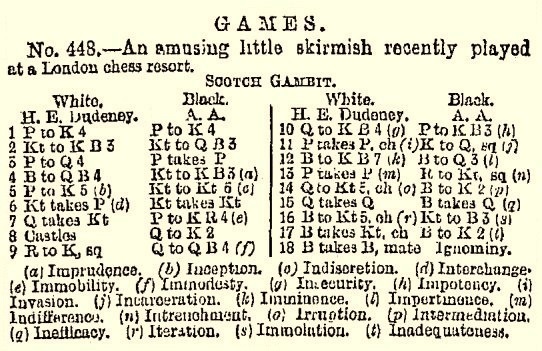

On pages 83-86 of How to Cheat at Chess (London, 1976) William R. Hartston offered advice on the art of annotating:

‘... For the benefit of the potential writer who may find himself forced to provide notes to some game he does not comprehend, we end this short course with a typical annotated game. All the notes (with very slight modifications where necessary) have actually appeared in chess journals during the past few years; most of them will probably appear again in the course of the next few years for they all bear the trade mark of an expert notewriter, in that they convey no precise information about the position and have that all-purpose look about them which is so useful when you feel like writing a note, but do not know what to say. We hope the reader will himself make full use of these notes when annotating games himself; in view of the forthcoming world shortage of original notes, he should find all he needs in this short game.’

Hartston then gave the 1 d4 e5 2 Qd2 version of the composed stalemate game (C.N. 3679), annotated with such observations as: ‘When Black can play this move safely he invariably solves his opening problems’, ‘Other lines cause the defence little difficulty’, ‘Those who are familiar with the teachings of Nimzowitsch will recognize his influence on the central play in this game’ and ‘This position had undoubtedly been foreseen by both players’.

But now Alan O’Brien (Mitcham, England) points out to us that most, if not all, of the 24 notes used by Hartston were taken from a single writer, i.e. from the two ‘Play the Experts’ Way’ articles on pages 75-77 of the March 1970 BCM and pages 100-103 of the April 1970 issue (the games Tukmakov v Tal and Jacobsen v Ljubojević). The articles were by W. Ritson Morry.

(3883)

From William Hartston (Cambridge, England):

‘All I can say to your correspondent is: well-spotted. That chapter of How to Cheat at Chess was based on an article I’d written earlier for Dragon (the magazine of the Cambridge University Chess Club) called “Write Notes The Expert’s Way” as a parody of Ritson Morry’s banalities in his BCM column. I’m not sure how many changes I made for the book – unlike some writers, I’m not a great fan of cut-and-pasting – but the basic material for that bit of the book certainly came from the Dragon article.’

(3886)

‘Even when games are annotated by the players themselves, most fall victim to the temptation to justify their decisions rather than explain them. Chess is not a precise science or even a totally logical game. Only after the result is decided do the annotators feel obliged to present the decisions in black and white. ...

All the more enjoyable therefore to come across the rare example of totally honest annotators of their own games. Of today’s great players I put complete trust in Larsen and Tal.’

Source: the chess column by W. Hartston in Now!, 8-14 August 1980, page 82.

(6742)

From page 91 of The Chess Masters on Winning Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1960):

‘Tartakower had a fluent pen; he wrote voluminously, often annotating a game for a newspaper or magazine while he was playing it.’

Is any further information available about this alleged practice?

(6930)

No information has yet been found on the practice ascribed by Reinfeld to Tartakower (the annotation of games during play). Daniel King (London) asks whether such writing would have been legal in many events of Tartakower’s time.

(6983)

From Leonard Barden (London):

‘I witnessed Tartakower making notes during at least one game, at one or more of the Southsea tournaments of 1949, 1950 and 1951, where we both participated. His game against Ravn at Southsea, 1951, which is in his Best Games collection, sticks in my mind.

On one occasion I was curious enough to creep up behind him to see exactly what he was doing. There was a dense sheet of variations and quite small writing, and I think he had some difficulty in reading his own material, pushing his spectacles back on his forehead, screwing up his eyes, and peering closely. I feel fairly sure that nobody objected. He was a legend, and the rules on consulting written material during play were more relaxed then than now.’

(6990)

C.N. 642 suggested ‘an interesting game in all its phases’ as ‘the Crown Prince of chess clichés’. For the title of King, ‘the rest is a matter of technique’ is doubtless a front-runner. Wanted: other nominations.

(7673)

‘A knight is a knight’ (C.N. 9253) brings to mind the cliché ‘a pawn is a pawn’ (a phrase used in a brief sketch by ‘W.C.G.’ on page 131 of the April 1885 BCM). C.N.s 642 and 7673 mentioned ‘an interesting game in all its phases’ and ‘the rest is a matter of technique’, and two others are ‘this move is better than its reputation’ and ‘the pawns fall like ripe apples’.

Readers are invited to keep their eyes peeled for any recent annotational clichés which have been spreading like wildfire, left, right and centre.

(9256)

C.N. 2639 above had the familiar ‘Further comment is not necessary’ (at move 15 of a 57-move game).

In the hope of gathering further material, we reproduce three quotes from C.N. 2545:

1) On page 271 of C.J.S. Purdy’s The Australasian Chess Review, 31 October 1938 the following appeared:

‘We consider Botvinnik the most brilliantly searching annotator in the world – the ordinary junk written by annotators doesn’t go down in Russia, where there are thousands who can pull bad notes to pieces.’

2) A comment on Georg Marco:

‘Even when it took him four years to annotate a game, as it sometimes did, his sense of humor was irrepressible just the same.’

Source: page 171 of Great Moments in Chess by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1963).

Evidence is still being sought regarding the amount of time Marco devoted to annotating. See too C.N.s 4855 and 5248.

3) When asked to name the best annotator, Tartakower replied (Wiener Schachzeitung, June 1929, page 169):

‘Kostić, who always pours out his soul, which is most amusing and instructive.’

C.N. 2543 mentioned that Kostić was hardly illustrious as an annotator, but that the exact point of Tartakower’s apparent quip is unclear.

(7819)

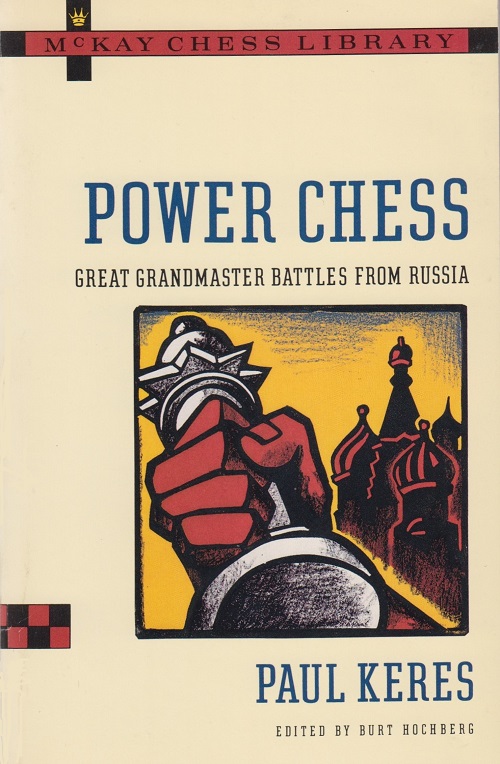

‘It is my considered opinion that Paul Keres is the greatest annotator who ever lived.’

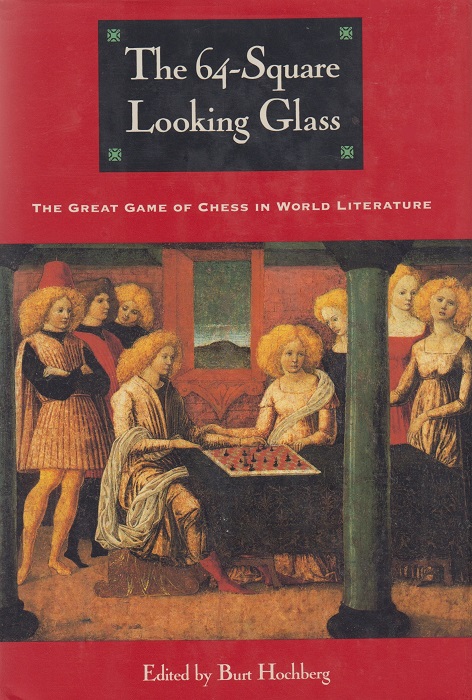

Burt Hochberg, a much underrated writer, made that comment in a laudatory review of the final volume of the Keres trilogy Grandmaster of Chess on pages 236-237 of the June 1969 Chess Life. (The production standards of the US publisher, Arco, were, however, criticized.)

After possible competing claims in favour of Alekhine, Botvinnik and Fischer had been noted briefly (with mention too of Bronstein), Hochberg wrote:

‘Keres is profound, analytically sound, most readable and instructive. He omits nothing, save the most obvious and trivial. But perhaps the feature that sets him above all the others is his sense of form. A game of chess, in common with some other forms of art, has a beginning, a middle and an end, one phrase preparing the next, every move part of a planned organic whole. In his notes, Keres imparts to the game a sense of direction, a feeling of anticipation and the sure knowledge that nothing has been left to chance, that everything has been taken into account. At frequent intervals, Keres reminds us of each player’s earlier strategic goals, pointing out the strengths and weaknesses of each position and setting forth the plans of each player for the next stage of the game. He also shares with the reader his own thoughts during the game. One frequently encounters the phrase, “During the game, I intended ...”.’

Keres was a columnist in Chess Life and Chess Life & Review, and in 1991 Hochberg brought out an excellent anthology, Power Chess.

The chess belles lettres book by Hochberg referred to in the back-cover blurb was The 64-Square Looking Glass (New York, 1993).

(11215)

Source: CHESS, 4 August 1956, page 295.

(8155)

On pages 70-71 of the February 1972 BCM Wolfgang Heidenfeld reviewed the magazine’s reprint of the Coburg, 1904 tournament book edited by P. Schellenberg, C. Schlechter and G. Marco. The annotations of Marco (‘as famed an analyst as a stylist’) were singled out for praise and the review concluded:

‘Such books are refreshing – and indeed very necessary – at a time when the erstwhile art of chess annotation has been reduced to an almost computerized routine, with mechanized symbols replacing the individual approach. The mass production era, with its demand on the reader’s time and the writer’s space, may make such mechanization inevitable – those of us who still enjoy a “well-spoken game of chess” will nevertheless deplore this development. It is to them that Coburg, 1904 will mean more than the record of a not very distinguished tournament.’

(8848)

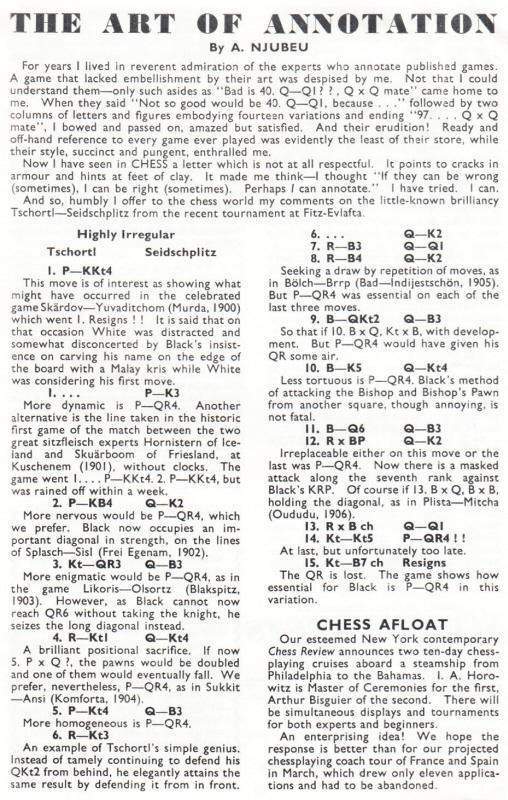

A game won by Henry Ernest Dudeney (1857-1930) was annotated in original style on page 7 of the Leeds Mercury Weekly Supplement, 23 October 1886:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Nf6 5 e5 Ng4 6 Nxd4 Nxd4 7 Qxd4 h5 8 O-O Qe7 9 Re1 Qc5 10 Qf4 f6 11 exf6+ Kd8 12 Bf7 Bd6 13 fxg7 Rg8 14 Qg5+ Be7 15 Qxc5 Bxc5 16 Bg5+ Nf6 17 Bxf6+ Be7 18 Bxe7 mate.

(8900)

Mike Salter (Sydney, Australia) expresses dislike of annotators’ unhelpful use of the single-word sentence ‘Desperation’ towards the end of games; he has counted 17 occurrences in Lessons from My Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1958).

Fine also used the word frequently in Chess Marches On! (New York, 1945). One example is in C.N. 8353.

(9330)

From page 25 of The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal by M. Tal (New York, 1976):

‘On the whole, I do not like annotating other people’s games. The point is that I consider that it is very difficult to penetrate into a player’s thinking, to guess the direction of the variations thought out by him, and therefore it is better to be indulgent towards one’s own games. I prefer to make my annotations “hot on the heels”, as it were, when the fortunes of battle, the worries, hopes and disappointments are still sufficiently fresh in my mind.’

On page 34 of the London, 1997 edition the wording was slightly different: ‘... it is better to direct one’s attention towards ...’

(9569)

Below is a remark by C.J.S. Purdy about Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters by Edward Lasker (New York, 1951) which was given in C.N. 9950. Lasker was described as:

‘One of the best chess writers and annotators of all time.’

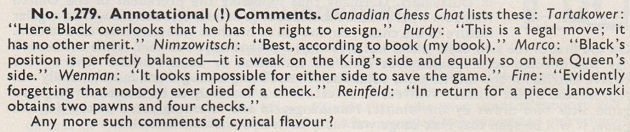

From page 278 of the September 1963 BCM, in D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column:

It will be appreciated if a reader can provide the item published in Canadian Chess Chat. For now, we give an extract from a column by George Koltanowski on page 10 of the Corpus Christi Caller-Times, 20 May 1962:

As ever, factual information about such quotations is sought. The Marco one was discussed in C.N. 5248, and the remark ascribed to Reinfeld should also mention Fine. It appeared on page 141 of the book on Lasker which they co-authored.

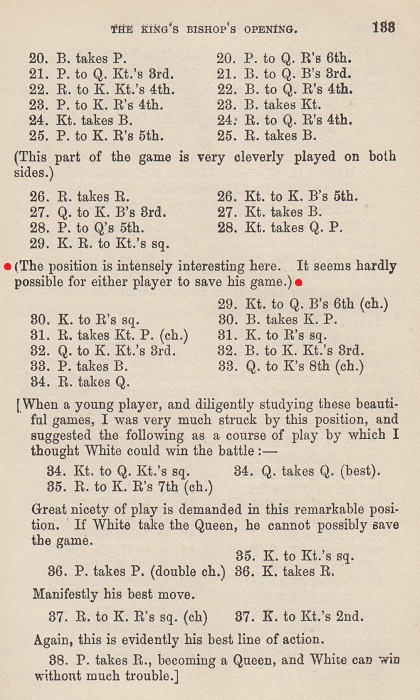

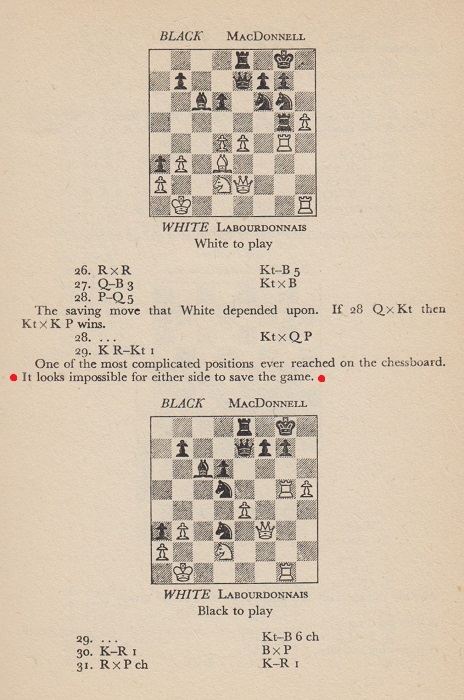

It is, though, the Wenman item that deserves particular attention, since it brings to mind a remark widely attributed to Staunton. For example, an article by G.H. Diggle reproduced in C.N. 7369 stated with regard to writers who annotated the 1834 Labourdonnais v McDonnell games:

‘Staunton himself, who did so (Chess Player’s Chronicle, volumes 1-3), really sums up the series in a famous note to game 21: “It seems utterly impossible for either player to save the game.”’

In an article about the Labourdonnais v McDonnell series on pages 277-281 of the July 1934 BCM Diggle wrote:

‘Some of their complications have driven annotators to despair. Staunton himself in one case can do no more than helplessly declare: “It seems utterly impossible for either player to save the game.”’

The article was reproduced on pages 69-75 of The Treasury of Chess Lore by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1951).

Presenting game 21 on pages 94-95 of Lessons in Chess Strategy (London, 1968) W.H. Cozens wrote:

‘Staunton’s note after White’s 29th move makes an apt comment: “It now seems hardly possible for either player to save the game.”’

However, pages 83-84 of The World of Chess by Anthony Saidy and Norman Lessing (New York, 1974) had the following with regard to a different game (50):

‘Beyond inserting a number of exclamation points it is useless to try to annotate this wildly uninhibited game. Howard Staunton, the famous English player, made the attempt some years later, only to give up with the historic remark: “It seems utterly impossible for either player to save the game!”’

It took us a while to find confirmation of Staunton’s words (in connection with game 21), on page 133 of his posthumous book Chess: Theory and Practice (London, 1876). Below is the relevant page in a late edition (London, 1920, published under the title The Laws and Practice of Chess):

That leaves the question of why Wenman’s name was introduced for a similar remark, and we can give a citation from his book One Hundred and Seventy Five Chess Brilliancies (London, 1947):

That unnumbered page is game 53 in Wenman’s book and is, of course, part of his coverage of the above-mentioned game 21 in the Labourdonnais v McDonnell series.

(10171)

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, Canada) sends, courtesy of Stephen Wright, the requested item in Canadian Chess Chat (page 45 of the February 1963 issue):

As shown in C.N. 10171, George Koltanowski had presented the same set of quotes, also without any sources, in a newspaper column about nine months previously. We should particularly like to know more about the remark attributed to Purdy.

(10182)

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) refers back to the ‘cynical’, sourceless annotation attributed to Tartakower, ‘Here Black overlooks that he has the right to resign’ (C.N.s 10171 and 10182).

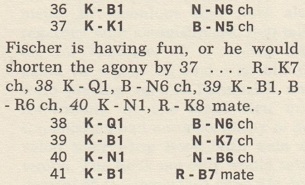

Our correspondent draws a parallel with a remark given in C.N. 202 (see page 233 of Chess Explorations). That item pointed out that page 27 of the Australasian Chess Review, 30 January 1936 quoted a comment by Tartakower concerning Alekhine’s move 30...Kh8 in the 12th match-game against Euwe in 1935:

Position after 30 Rxc1

We add that a similar annotation was attributed to Tartakower on page 127 of CHESS, 14 December 1935:

Tartakower covered the world championship match for De Telegraaf, and below is his note on page 9 of the 30 October 1935 edition of the Dutch newspaper:

Although the Australasian Chess Review and CHESS both had the adjective ‘excellent’, the usual meaning of ‘geschikte’ is ‘suitable’, and a more literal translation of Tartakower’s remark ‘Hier mist zwart een geschikte gelegenheid om op te geven’ would therefore be ‘Here Black missed a suitable opportunity to resign’. That, though, is far less quotable than ‘Here Black missed excellent resigning chances’. It is difficult to judge how much humour and/or irony Tartakower’s note in Dutch was intended to convey.

(10202)

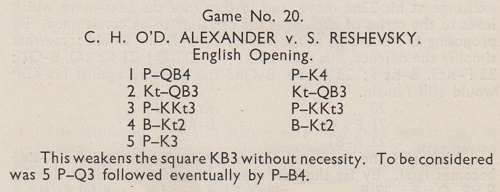

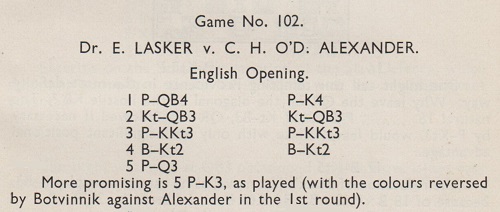

Which move is preferable, 5 d3 or 5 e3?

On pages 67 and 265 of his book on Nottingham, 1936 Alekhine gave contradictory comments about the position after 1 c4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 g3 g6 4 Bg2 Bg7:

As mentioned in C.N. 2109 (see page 281 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves), the discrepancy was pointed out by T.V. Parrott on page 153 of CHESS, May 1953 and by Arthur Oliver on page 105 of Chess World, June 1962. A later reference is page 15 of Chess Life, January 1963 (in a ‘Chess Kaleidoscope’ article by Eliot Hearst).

(10172)

From Yasser Seirawan (Amsterdam):

‘Despite Alekhine’s contradictory comments, both the moves that he mentions, 5 d3 and 5 e3, are considered to be main lines of play in modern opening theory.

In his recent works on the English Opening, Mihail Marin has advocated 5 e4, and I wonder whether Alekhine might have suggested that that move weakens f3, d3 and d4. The most surprising comment by Alekhine is that after 5 d3 White may, in time, aspire to play f4; in modern games that simply does not happen.

In view of the forthcoming middlegame, modern masters would judge 5 d3 to be the prelude to a queen’s-side expansion, most often seen with the maneuver Rb1, b4 and b5, chasing away the c6-knight and improving the view of the g2 bishop.

Conversely, 5 e3 is considered rather more flexible. White signals that he intends a central expansion with Nge2, perhaps followed by the advance d4. In that line, White can sometimes also pursue a queen’s-side expansion, as mentioned above, after playing d3. The key difference is that the king’s knight is developed to e2 instead of f3, and in this case White will usually play f4, to counter-act an aggressive king’s-side expansion by Black.

In short, modern theory considers that the two moves given by Alekhine, 5 d3 and 5 e3, are equally good.’

(10176)

From page 267 of Deep Thinking by Garry Kasparov with Mig Greengard (New York, 2017):

‘I was told this story in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and have no way to know if it’s true. But it definitely sounds like something Fischer might say. It is also bitingly insightful, as few fans would have any idea of the quality of a world champion’s game without expert commentary. Today it’s quite different, when everyone has a super-strong engine at his disposal and feels empowered to scoff at the champion’s mistakes as if they’d found them themselves.’

Kasparov’s observation about people pointing out a champion’s mistakes ‘as if they’d found them themselves’ makes us wonder how often he has been the victim of a common piece of annotational malpractice: in a book or article a champion (e.g. Capablanca or Alekhine) presents analysis which is an improvement on his actual play, and a subsequent annotator (e.g. Panov or Kotov) reproduces the same variations anonymously, as if they were his own discovery. There cannot be many areas of human activity where a critic has the opportunity to act that way.

(10433)

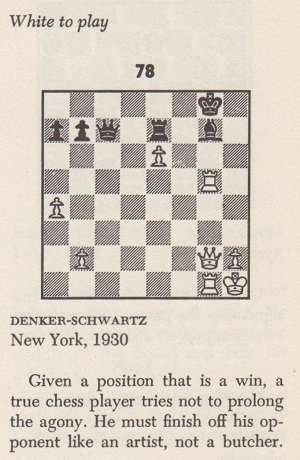

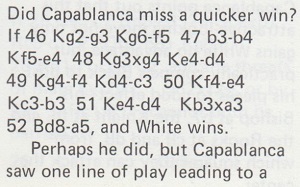

Annotators and chroniclers often have difficulty deciding to what extent players who miss faster or easier wins should have such lapses pointed out. To illustrate the theme, we present a range of observations in books by Irving Chernev.

Combinations The Heart of Chess (New York, 1960), page 37

Denker won quickly with 34 Qd5 Kf8 35 Rxg7. The artist/butcher remark is reminiscent of an observation by Emanuel Lasker on page 68 of the Chess Player’s Scrap Book, May 1907 in connection with the game Morphy v the Duke and Count.

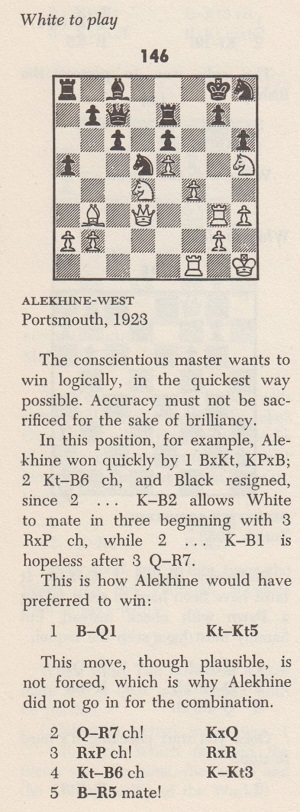

Combinations The Heart of Chess (New York, 1960), page 74

Logical Chess Move by Move, various editions, Game 27 (Chekhover v Rudakovsky, Moscow, 1945)

The almost identical text was on pages 193-194 of The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played (New York, 1965).

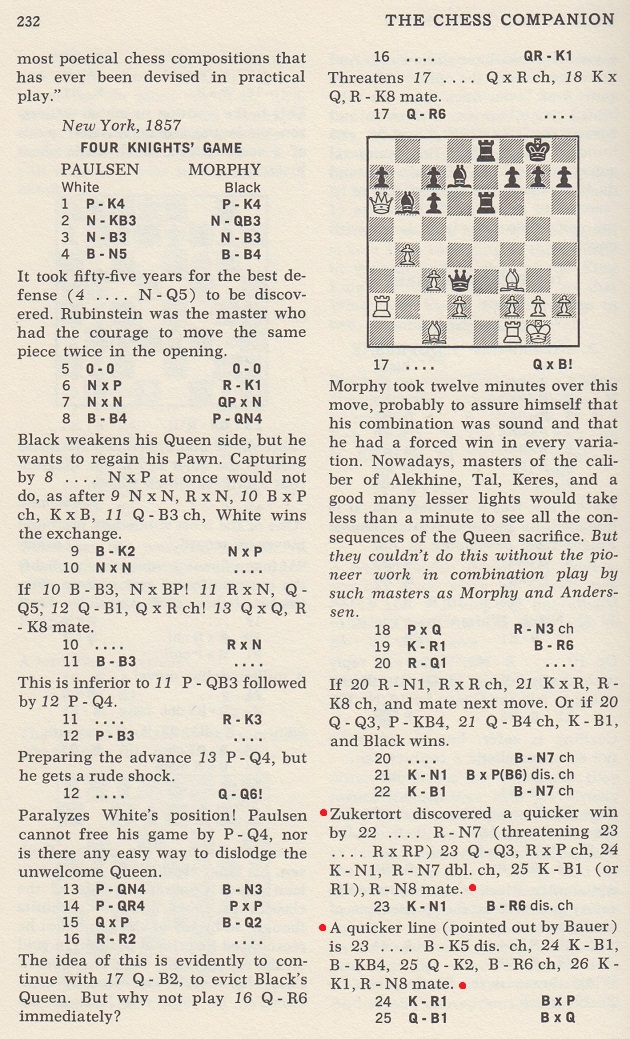

Another example is Paulsen v Morphy, New York, 1857:

The Chess Companion (New

York, 1968), pages 232-233

The next position comes from a famous brilliancy by Capablanca (White) against Juan Corzo, Havana, 1901:

The Golden Dozen (Oxford, 1976), page 284

Virtually the identical text had appeared on pages 175-176 of The Chess Companion.

The ‘commentator’ in question was Fred Reinfeld, in The Immortal Games of Capablanca (New York, 1942). In My Chess Career (London, 1920) Capablanca wrote:

‘Today, very likely, I would simply have played Q-Q2 and won also, but at the time I could not resist the temptation of sacrificing the queen. At any rate, the text move was the only continuation which I had in mind when I played P-K6.’

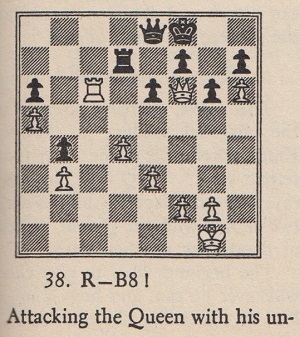

From later in the same game, where Capablanca played 46 Kf2:

Capablanca’s Best Chess Endings (Oxford, 1978), page 7

Neither Capablanca nor Reinfeld mentioned 46 Kg3. On pages 228-230 of Combinations The Heart of Chess Chernev made no adverse comment on either 29 Qxb5 or 46 Kf2.

A final illustration of the difficulty of avoiding inconsistency comes from page 255 of The Chess Companion, in the conclusion to D. Byrne v Fischer, New York, 1956:

Our feature article on the game shows that the future world champion’s own small book, Bobby Fischer’s Games of Chess, made no reference to the faster mates available at move 36 (...Rf2+) and at move 37 (...Re2+). Those lines would have given mate just one move earlier, and their noteworthiness is a matter of opinion. It is curious, though, that Chernev mentioned only one of the two.

(11105)

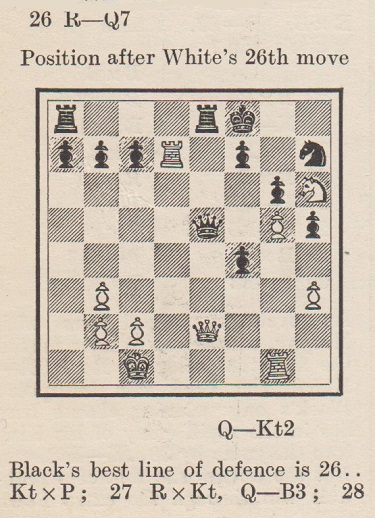

White to move

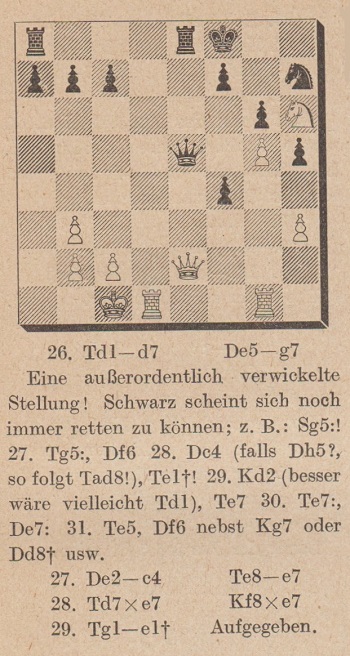

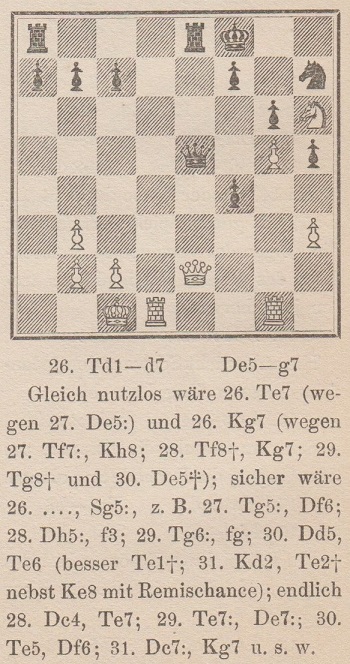

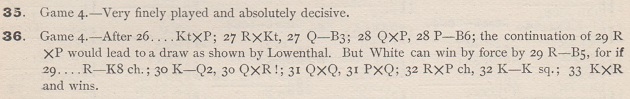

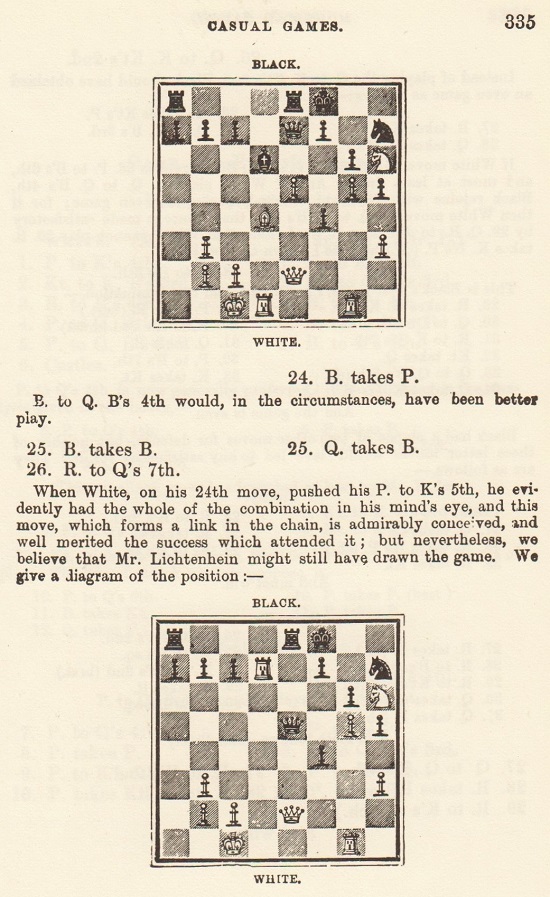

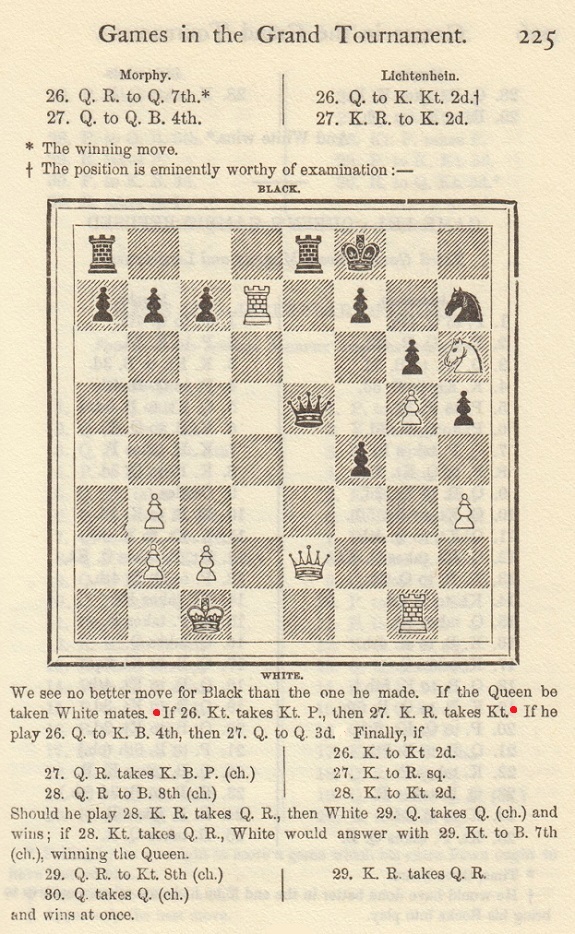

Leaving his queen en prise, White threatened mate with 26 Rd7. The possible rejoinder 26...Nxg5 has received much attention, but the present item focuses on the issue of due attribution of analysis rather than the analysis itself.

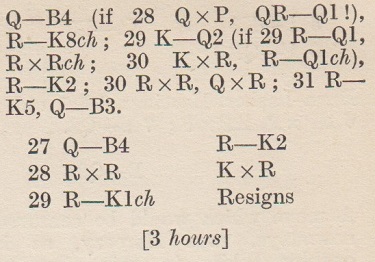

The position arose in Morphy’s well-known victory over T. Lichtenhein in the 1857 New York tournament. Working backwards, we begin with page 48 of the 1994 book Magic Morphy by C. Abravanel and P. Clère, which attributed the critical line, beginning 26...Nxg5 27 Rxg5 Qf6, to P.W. Sergeant:

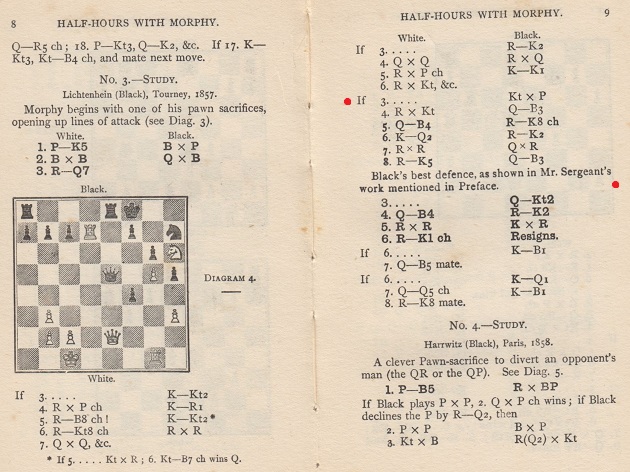

Another example comes from pages 8-9 of the 1922 edition of Half-Hours with Morphy by E.E. Cunnington:

From page 47 of Sergeant’s 1916 monograph on Morphy:

However, when that line was given by Reinfeld on page 13 of the January 1955 Chess Review it was credited to Maróczy:

See also pages 59-60 of the 1974 Reinfeld/Soltis book Morphy Chess Masterpieces, which stated that 26 Rd7 (‘!’) ‘loses against inspired defense’ but that Lichtenhein missed ‘the beautiful defense pointed out by Maróczy, the great Hungarian player and analyst’.

Below is Maróczy’s note in his 1909/1925 book on Morphy (pages 35-36 and 23 respectively):

From page 49 of the third edition (1894) of Paul Morphy. Sein Leben und Schaffen by Max Lange:

The game was discussed on pages 132 and 135 of Steinitz’s 1889 book The Modern Chess Instructor, with these notes regarding 26 Rd7 and 26...Qg7:

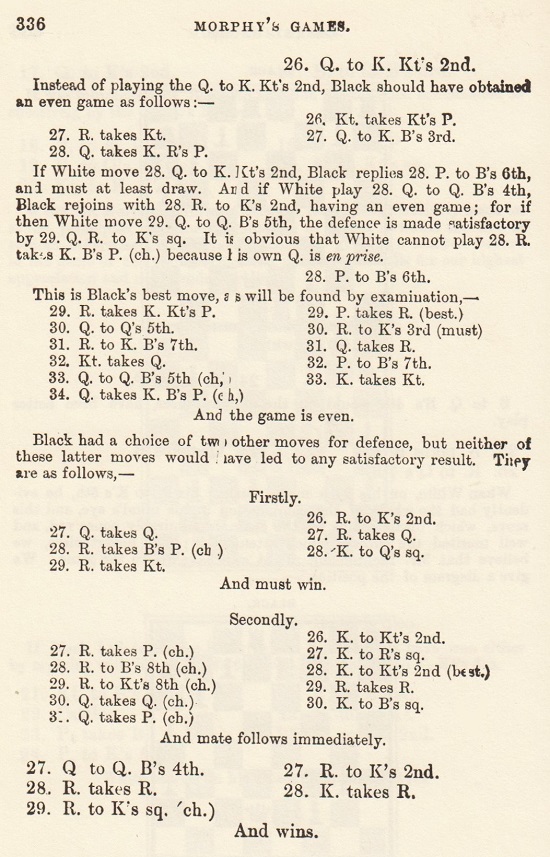

The reference to Löwenthal concerns pages 335-336 of his 1860 monograph on Morphy:

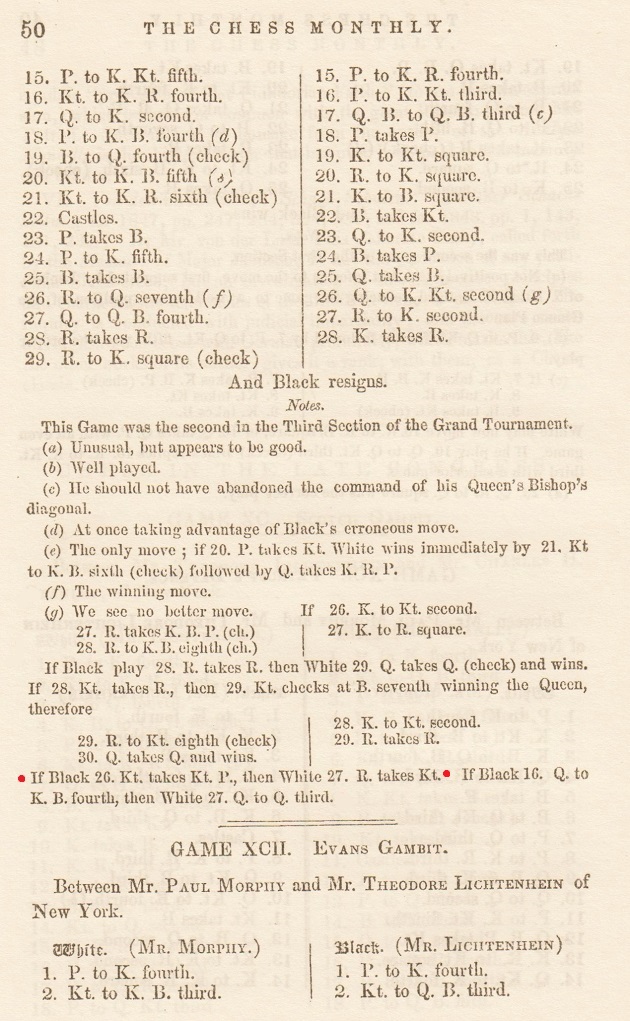

Two earlier publications of the game:

New York, 1857 tournament book (1859), page 225

Chess Monthly, February 1858, page 50

See too page 45 of the 1995 work Tízezer Lépés Morphyval by C. Gerencsér. The latest detailed analysis of the game appears to be in Morphy move by move by Z. Franco (2016). The note after 26...Qg7 (‘?’) on page 89 is 16 lines long but mentions no prior annotators. That hardly seems right, but the game illustrates the difficulty of deciding how moves, lines and ideas can best be credited to analytical predecessors. The matter was addressed by Sergeant in the Preface to his Morphy games collection (page v):

‘In the annotation of the games I have made full use of all the recognized authorities in my possession or within my reach, including the books of Löwenthal, Lange and Maróczy, and the scattered criticisms of Zukertort, Steinitz, Lasker, etc. Where I have been able to trace the original source of an important note, I have usually acknowledged it; but the habit of so many analysts of borrowing without acknowledgement makes it impossible to do this in many cases.’

(11485)

Addition on 24 December 2024:

On page 12 of the New York Evening Post, 22 June 1907 Emanuel Lasker’s column began:

‘The following game [Bird’s Opening] was played in the “champions’ tournament”at Ostend between Amos Burn, the British representative, and Chigorin, who represented Russia. It is one of those games in which analysis cannot be instructive. The Russian has a wrong idea, and after ten moves is so much pledged to it that against accurate play he must lose. This is what he has to contend against in this game. Chigorin makes repeated and heroic attempts to remove obstacles, but is always met by a phlegmatic defence which is most disheartening. At the same time, from the highest standpoint of chess it is always gratifying to find examples where true principles prevail over mere ingenuity, caprice, or predilection.’

For examples of how great masters’ texts have been altered, see Fischer’s Fury and Capablanca Book Destroyed. Further comments are given in Chess and the English Language. See also Castling in Chess (showing annotations with illegal proposals of O-O or O-O-O), Chess Punctuation, Chess Notation and Copying. Attention is furthermore drawn to the entries on parodies/spoofs in the Factfinder, as well as games annotated with quotations from Shakespeare.

From the front cover of the October 1966 issue of CHESS:

The unnamed author was P.H. Clarke.

Concerning the observation by C.H.O’D. Alexander – ‘It passes one of the best tests of a well-annotated book: the winner’s moves are quite frequently criticised’ – that full review is sought. The words were not in the chess column on page 39 of the Sunday Times Magazine, 7 May 1961, where Alexander compared the Clarke book favourably to Selected Games of Mikhail Tal by J. Hajtun (London, 1961).

(12154)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.