Edward Winter

Chess Review, July 1967, page 198

The following position occurred in a correspondence game between Edgar Odson and H.F. Arnold:

White played 60 Bd8+ and announced mate in 24 moves.

Source: American Chess Bulletin, December 1911, page 278. Other little-known (alleged) examples – and verifications – of long announced mates would be welcome.

(1753)

An analytical addition (1999) from Richard Forster on page 5 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

‘It would seem to be true, e.g. 60 Bd8+ Ke8 61 Kf6! (61 Bf6 is less accurate because of 61...Re4+ 62 Kd5 Bxe6+ 63 Rxe6+ Kd7!?) and now:

a) 61...Re4 62 Be7 Rxe6+ 63 Rxe6 Bxe6 64 Kxe6 f4 65 Kf6 f3 66 Bc5 f2 67 Bxf2 Kf8 68 Bd4 Ke8 69 Kg7 Kd7 70 Kxh7 Ke6 71 h5 gxh5 72 g6 Kf5 73 g7 Ke4 74.g8(Q) etc., or

b) 61...Bxe6 62 Kxe6 Rxc3 63 Bf6 Rc8 64 Rxa6 followed by Ra6-a7xh7 and h5.

In both variations White can probably mate by move 84.’

In a report on page 5 of the 23 January 1989 issue of Inside Chess John Hillery records that in round two of a tournament held in Long Beach in November 1988 the Deep Thought computer announced a mate in 19 moves.

The score is already doing the rounds (e.g. page 66 of the February 1989 Scacco), so we refrain from giving it here. Is 19 a record (so far)?

(1800)

Below are some more little-known announced mates. We should like to learn a) whether a computer check can prove any of them unsound, and b) the longest forced mate that any computer can currently verify.

J. Winter-J.T. Beckner, Chicago, 1913

23...Qd5 was played. ‘Here Black announced mate in 13 moves. As White continued, it was accomplished in ten.’ The game ended: 23...Qd5 24 e4 fxe4 25 Ng3 Qg5 26 Qxg2 Qh6+ 27 Nh5 Qxh5+ 28 Kg3 Qg4+ 29 Kf2 Qxg2+ 30 Ke3 Rf8 31 Rhe1 Qg5+ 32 Kf2 Bd1 mate.

Source: American Chess Bulletin, October 1913, page 227.

Richard Forster wrote on page 6 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

‘I am convinced that this announcement is not correct. E.g. 24 Qxg2 Bxg2+ 25 Kh2 Bxh1 26 Rxh1 Qf3 27 Ng3 Qf2+ 28 Kh3 Rf8 29 d5 Qxb2 30 dxe6 Rf6 31 Nxf5, etc.

In the game line, 25 Qxf3 exf3 26 Nf4 Qg5 27 Nxg2 Qxg2+ 28 Kh4 Rf8 29 Rcg1 Rf4+ (29…Qxb2 30 Kg3) 30 Kh5 g6+ 31 Kh6 Qxb2 (31…Qd2 32 Rxg6+ hxg6 33 Bc1 Rh4+ 34 Kxg6 Qg2+ 35 Kf6) 32 Bxg6 Rf6 33 Kh5 hxg6+ 34 Rxg6+ Rxg6 35 Kxg6, etc.

There are other improvements too:

a) 28…Qg5+ 29 Kf2 Qd2+ 30 Kg3 Qxg2+ 31 Kf4 Rf8+ 32 Ke5 Qg3+ 33 Kxe6 Qd6 mate.

b) 30…Qg5+ 31 Kf2 Rf8, and mate in three.

c) 31 d5 delays the mate until move 37.’

From Nine Chess Positions:

Black to move

Forster-Wheeler, Correspondence game, USA

White having just played 23 h3, Black announced mate in 16 moves.

Source: La Stratégie, 15 January 1877, pages 8-9.

S. Kruger-C.G. Watson, Telegraphic match (New South Wales v Victoria)

White has just played 35 hxg6, and Black had a ‘simple mate in 13’ which he did not find until after the game: 35...Qd5+ 36 Kg1 Re1+ (Watson played 36...Qc5+ and drew.) 37 Kf2 Qd2+ 38 Kf3 Qe2+ 39 Kf4 Rf1+ 40 Kg5 f6+ 41 Kh4 Qxh2+ 42 Kg4 Qe2+ 43 Kh4 Rh1+ 44 Rh3 Qf2+ 45 Kg4 Rg1+ and mate in two moves more.

Source: Chess World, 1 January 1950, pages 11-12.

J. Bannet-W.P., Correspondence, 1896-97

White announced mate in 14 moves.

Source: La Stratégie, 15 March 1898, pages 71-72.

A note by Richard Forster on page 7 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

‘Actually it is a mate in ten: 1 Bxd6+ cxd6 2 Rf6+ Kg7 3 Rf7+ Kh6 (or 3...Kg8 4 Rf5+, e.g. 4...Kg7 5 Qf7+ Kh6 6 Rxh5+ Kxh5 7 Qf3+ Kh6 8 Ne6 g5 9 Qf6+ Kh5 10 Qxg5 mate) 4 Qe3+ Qg5 (4...g5 5 Nf5+ Kg6 6 Qe6 mate) 5 Nf5+ gxf5 6 Rf6+ Kh5 7 Qf3+ Qg4 8 Rxf5+ Kh4 9 g3+ Kh3 10 Qg2 mate.’

I.A. Gutierrez-H.C. Davis, Correspondence game

White announced mate in 14 as follows: 31 Qe7+ Kd5 32 Na5 Rf6 33 c4+ Kd4 34 Qc5+ Kd3 35 Qe3+ Kc2 36 Qb3+ Kd2 37 Bb4+ Kc1 38 Qc3+ Kb1 39 Ba3 Rxf2 40 Kxf2 e3+ 41 Kxe3 Rb8 42 Nb3 Rxb3 43 axb3 any 44 Qb2 mate.

Source: American Chess Bulletin, February 1920, page 39.

(2045)

J. Ken MacDonald (Etobicoke, Canada) reports that in the Gutierrez v Davis position his computer found a forced mate in six moves: 1 Ne3 Rc5 2 Bxc5 Bd7 3 Qd6+ Kf7 4 Qxd2+ Kg6 5 Qf5+ Kh6 6 Ng4 mate.

(2066)

Richard Forster observed on page 8 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves that in the announcement too several short-cuts were missed (e.g. 34 Nb3+, 36 Nb3 and 39 Nb3).

C.N. 1371 (see Chess Explorations, page 164) discussed two brevities (Taylor v Amateur, London, 1862 and Potter v Amateur, London, 1872) featuring announced mates which were longer than the games themselves. We have now noted the game below, which appeared on pages 434-435 of the September 1907 BCM and ‘was played at board 26 in the recent correspondence match Midland Union v Southern Union’.

H.R. Barker – A.H. Owen

Correspondence game

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Bc5 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 c3 Nf6 5 O-O O-O 6 d3 d5 7 exd5 Nxd5 8 Bxd5 Qxd5 9 Be3 Bg4 10 Bxc5 Qxc5 11 h3 Bxf3 12 Qxf3 Rad8 13 Na3 Rd7 14 Rad1 Rfd8 15 Rd2 Qd6 16 Rfd1 Qg6 17 Qe2 h6 18 Nc4 Re7 19 Re1 b5 20 Ne3 a6 21 b4 f5 22 Qd1 Red7 23 Nc2 f4 24 Re4

24...Qxe4 (‘Black with this move announced mate in 25 moves or less. White replied, I resign after your 36th move. Of course, I could vary the form of checks, and drive your king to shelter; but this would be as futile as unsportsmanlike.’) 25 dxe4 Rxd2 26 Qg4 Rxc2 27 Qe6+ Kh7 28 Qxc6 Rd1+ 29 Kh2 Rxf2 30 Qe6 Rff1 31 Qf5+ Kg8 32 Qe6+ Kf8 33 Qf5+ Ke8 34 Qxe5+ Kd8 35 Qd5+ Rxd5 36 exd5 Ra1 37 a3 Kd7 38 g4 Ra2+ 39 Kg1 Kd6 40 h4 Kxd5 41 g5 Ke4 42 gxh6 gxh6 43 Kf1 Kf3 44 Ke1 Kg2 45 Kd1 f3 46 Kc1 f2 47 Kb1 Re2 48 any fl(Q) mate.

(2142)

A further example:

M.E. Goldstein-P. Rocks Correspondence game, 1920

‘A brilliant ending where White sacrificed two rooks and then announced mate in 14’ – BCM, February 1921, page 51.

22 Nxg7 Qxc3 23 Rh8+ Kxh8 24 Qxh6+ Kg8 25 Nf5 Qxa1+ 26 Kf2 Nf6 (The BCM says that Black could have avoided defeat by 26…Rc2+ 27 Kg3 Re2, after which White would have only perpetual check.)

‘White now announced mate in 14 by 27 Qf8+ Kh7 28 Qxf7+ Kh8 29 Qh5+ Kg8 30 Nh6+ Kh8 (30…Kg7 31 Qg5+ Kh7 32 Qg8+ and mate in five) 31 Qe8+ Kg7 32 Qg8+ Kf6 33 Qf7+ Kg5 (Now it would be mate in four with 34 f4+.) 34 Qf5+ Kxh6 35 Bf8+ Qg7 36 Qf6+ Kh5 37 Bxg7 Rc2+ 38 Kg3 Rxg2+ 39 Kxg2 any 40 Qh6 mate.’

We are still seeking games with announced mates longer than the games themselves. The following, given on page 151 of P. Anderson Graham’s monograph on Blackburne, is a borderline case:

J.N. Burt – J.H. Blackburne (simultaneous)

Bristol, 1869

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 Bg7 5 c3 g4 6 Qb3 gxf3 7 Bxf7+ Kf8 8 Bxg8 Rxg8 9 O-O

Here Blackburne announced mate in nine moves: 9...Bd4+ 10 Rf2 Rxg2+ 11 Kf1 Rxf2+ 12 Ke1 Rf1+ 13 Kxf1 Qh4 14 Qb4+ d6 15 Qxd6+ cxd6 16 cxd4 Bh3+ 17 Kg1 Qe1 mate.

(2166)

Richard Forster noted on page 10 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

‘The announcement is correct, but 13...Qh4? allows 14 cxd4 and White escapes immediate mate, though not defeat. The correct line is 13...Qg5!, i.e. 14 Qb4+ c5 15 Qxc5+ Bxc5 16 d4 Qg2+ 17 Ke1 Qe2 mate.’

Here is a further alleged case of an announced mate longer than the game itself:

Arthur William Daniel – T.A. Grant

Correspondence game, 1911-12

Four Knights’ Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nc3 Nc6 4 Bb5 d6 5 d4 Bd7 6 O-O Be7 7 Re1 exd4 8 Bxc6 Bxc6 9 Nxd4 O-O 10 Re3 Bd7 11 Rg3 c6 12 f4 Qc7 13 f5 d5 14 Bh6 Bd6

White announced mate in 21 moves.

Source: the Chess Amateur, June 1912, page 648.

Here we break off, partly to allow readers to examine the various lines for themselves but mainly because we would not know where to begin in trying to summarize the thousands of moves of analysis which, over the ensuing year, the Chess Amateur published from the pen of A.W. Daniel, i.e. up until he wrote on page 242 of the May 1913 issue:

‘The analysis of the above ending is now brought to a conclusion. No error has been pointed out, hence it seems reasonable to assume that the position is a forced mate in 21 moves as indicated.’

(2529)

Our CD-ROM Jeux d’échecs was out of its depth in verifying a mate in ten which Berthold Suhle (1837-1904) announced in a game, one of eight played in a simultaneous blindfold display, against Kronenberg in Bonn on 20 December 1858:

White to move

24 O-O-O c5 25 Rde1 Bb7 26 Ne5 Bd5 27 Ng6 Bf7 28 Re4+ Ne7 29 Bxe7 Nc6 30 Bg5+ Ne7 31 Bxe7 any 32 Bg5+ Be6 33 Rf8 mate.

Sources: Deutsche Schachzeitung, January 1859, page 30 and the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1859, pages 71-72. The Chronicle wrote of Suhle, ‘a new star has also appeared on the chess horizon which threatens to dim the light of the Morphy star’. It is certainly rare to find an (alleged) announced mate which begins with castling, especially on the queen’s side and without check.

(2199)

One of four games which White played simultaneously without sight of the boards:

Ladislas Maczuski – A. Mazzolani

Ferrara, 31 May 1876

Danish Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 Bc5 4 Bc4 Qf6 5 Nf3 h6 6 cxd4 Bb6 7 Nc3 Ne7 8 e5 Qg6 9 Bd3 f5 10 exf6 Qxf6 11 Ne4 Qf7 12 Ne5 Qe6 13 Qh5+ g6 14 Qh4 Nf5 15 Nf6+ Kf8 16 Bxf5 Ba5+ 17 Kf1 Qxf5

White announced mate in 11 moves.

Source: La Stratégie, 15 June 1876, pages 172-173.

A computer check indicates that the finish could be one move faster, i.e.: 18 Bxh6+ Ke7 19 Ng8+ Ke6 20 Qe7+ Kd5 21 Qc5+ Ke6 22 d5+ Kxe5 23 Bg7+ Kf4 24 Qe3+ Kg4 25 Nf6+ (25 Qg3+ takes a move longer.) 25…Qxf6 26 Bxf6 and mate next move.

Regarding Black’s identity, La Stratégie gave ‘A. Mazzonali’, but we feel that Mazzolani must be correct. Ferrara had two chess figures of the latter name, Alessandro and Antonio.

(2335)

This position was published on page 335 of La Stratégie, 15 October 1896:

White to move

However improbable it may seem, the caption reads ‘A curious ending played recently in Havana’, the players being named as A.C. Vázquez and A. Fiol. White, it is said, announced mate in three moves. Has there ever been a more unlikely claim that a position arose in actual play?

(2413)

Below are the reminiscences of the Reverend Roger John Wright of a blindfold simultaneous display (13 boards) given by Zukertort in Norfolk, England in 1872:

‘On this occasion a very amusing incident occurred, for one of our best players, anxious to perpetrate “a bit of Morphy”, solemnly announced mate in five moves. “Ah, ah!”, cried the blindfold savant as quick as thought (the very tone of his voice betraying how irrepressibly he was tickled at the idea), “is zat so? Good, very good; but I will give you ze mate in three! Paw-rn to Rook’s fo-urth, sheck!” etc., giving the would-be Morphy the coup de grâce in splendid style, and leaving him dumbfounded.

Source: The Chess Bouquet by F.R. Gittins (London, 1897), pages 34-35.

(2771)

For further information about Zukertort in Norfolk, see Chess Jottings.

White, to move, announced mate. In how many moves?

(3121)

The answer is that White announced mate in 12 moves.

Below is the full game-score, as published on pages 21-22 of Pierce Gambit, Chess Papers and Problems by J. Pierce and W.T. Pierce (London, 1888):

William Timbrell Pierce – W. Nash

Correspondence, circa 1885

Pierce Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 exf4 4 Nf3 g5 5 d4 g4 6 Bc4 gxf3 7 O-O Qg5 8 Rxf3 Nxd4 9 Bxf7+ Kxf7 10 Rxf4+ Nf6 11 Nd5 Qe5 12 Rxf6+ Kg8.

This gives the position in the above diagram. Here the Pierces’ volume stated:

‘White announced mate in 12 moves. The mate is accomplished thus: 13 Qg4+ Bg7 14 Bh6 (White can here mate in three moves, thus: 14 Qxg7+ Kxg7 15 Bh6+ Kg8 16 Rf8 mate.) 14...Qxf6 15 Nxf6+ Kf7 16 Qxg7+ Ke6 17 Ng8 Rxg8 18 Qxg8+ Kd6 19 Qd5+ Ke7 20 Bg5+ Kf8 21 Rf1+ Nf3+ 22 Rxf3+ Kg7 23 Qf7+ Kh8 24 Qf8 mate.’

The reference ‘circa 1885’ included in the game heading above is taken from pages 104-105 of a book published some years later, Chess Sparks by J.H. Ellis (London, 1895). It too mentioned the short mate, although in rather paradoxical terms:

‘White announced mate in 12 moves, overlooking, as was perhaps only natural in a correspondence game, a much prettier mate in four moves.’

A number of readers believed that from the diagram the quickest mate was in five moves, rather than four. They regarded 13…Qg5 as delaying the mate by one move, whereas it accelerates it by one (14 Qxg5+ Bg7 15 Ne7 mate or 14 Ne7+ Bxe7 15 Qxg5 mate).

(3130)

Tim Harding (Dublin) reports that when the game was published on pages 12-13 of the January 1886 BCM the move order appeared as 5 Bc4 g4 6 d4, it being indicated that White had intended to opt for his new idea of 5 d4 but instead, by a clerical error, played the usual move, 5 Bc4. Moreover, the game was indeed played in 1885, in a tournament (one of a series of correspondence events) organized by the English Mechanic.

(3147)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) sends this game from page 112 of The Globe (Buffalo), November 1876:

A.P. Barnes – F.W.

New York, circa 1876

Petroff Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Bc4 Nxe4 4 Nc3 Nxc3 5 dxc3 d6 6 Nxe5 Qe7 7 Bxf7+ Kd8 8 O-O Qxe5 9 Re1 Qf6 ‘and White announced mate in 11 moves’.

However, this is not an instance of an announced mate which is longer than the game itself (see page 164 of Chess Explorations, pages 8-10 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves and page 50 of A Chess Omnibus), because from the diagrammed position there is a mate in nine.

(5946)

Regarding instances of an announced mate which is longer than the game itself, the following encounters have been discussed in C.N.:

The accuracy of the last two cases has yet to be demonstrated.

In C.N. 5946 we remarked concerning Barnes v F.W., New York, circa 1876:

‘However, this is not an instance of an announced mate which is longer than the game itself (see page 164 of Chess Explorations, pages 8-10 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves and page 50 of A Chess Omnibus), because from the diagrammed position there is a mate in nine.’

In the light of a comment received from Stephan Bird (Caernarfon, Wales) we clarify that in this topic ‘announced mate’ refers to a correct announcement of the shortest possible forced mate.

(5949)

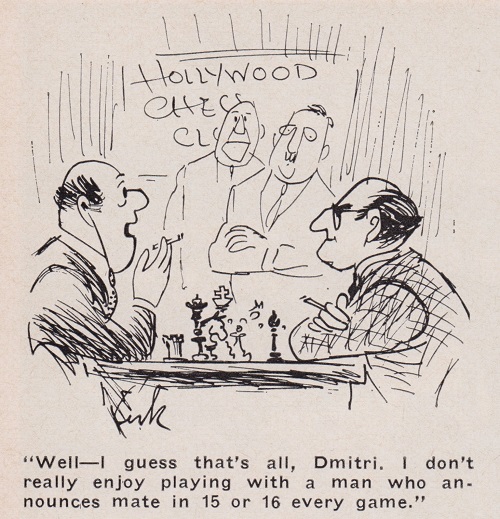

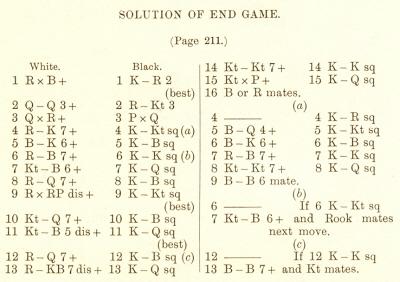

Marc Hébert (Charny, Canada) asks for information about the famous blindfold game in which J.H. Blackburne announced mate in 16 moves.

The conclusion was published on page 211 of Mr Blackburne’s Games at Chess by P. Anderson Graham (London, 1899), with the solution on page 326:

Thus the only information supplied was Black’s name: Scott. It was not stated that the game had occurred in a simultaneous display, although that assumption is commonly made.

The position was given on page 41 of Blindfold Chess by E. Hearst and J. Knott (Jefferson, 2009), the co-authors stating that they had been unable to find any further particulars. Where, if anywhere, was the position published before the appearance of P. Anderson’s Graham book? We also seek bare references in nineteenth-century sources to such a game, or to an opponent of Blackburne’s named Scott.

(6691)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) draws attention to the Sydney Mail of 19 February 1887 (page 411), which reproduced from the Fortnightly Review an article by L. Hoffer entitled ‘The Chess Masters of Today’. It was stated:

‘There are masterpieces of Blackburne’s blindfold games published in which he has announced checkmate in 17 moves.’

We note that the same remark appeared on page 162 of the Chess Monthly, February 1889.

Which games published before 1887 could Hoffer have had in mind?

Taylor Kingston (Shelburne, VT, USA) comments regarding the position in C.N. 6691, where Blackburne is said to have announced mate in 16 moves, that White can give mate in eight. After 1 Rxe6+ Kh7 2 Qd3+ Rg6 the announced mate was 3 Qxg6+ fxg6 4 Re7+ Kg8 5 Be6+ Kf8 6 Rf7+ Ke8 7 Nf6+ Kd8 8 Rd7+ Kc8 9 Rxa7+ Kb8 10 Nd7+ Kc8 11 Nc5+ Kd8 12 Rd7+ Kc8 13 Rf7+ Kd8 14 Nb7+ Ke8 15 Nxd6+ Kd8 16 Rd7. The analysis engine Rybka agrees that this is the best play for both sides if White chooses 3 Qxg6+, but it gives the line 3 Rxg6 fxg6 4 Qxd6 Qd1+ 5 Bxd1 gxh5 6 Qe7+ Kh8 7 Bd4+ Kg8 8 Qg7 mate.

(6698)

White to move

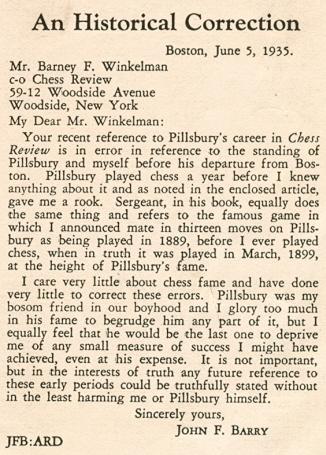

C.N. 4582 remarked that the familiar Barry v Pillsbury game (in which White announced mate in 13 moves) is commonly misdated 1889, instead of 1899.

We add a letter from Barry published on page 185 of the August 1935 Chess Review:

(6979)

See too C.N. 11851.

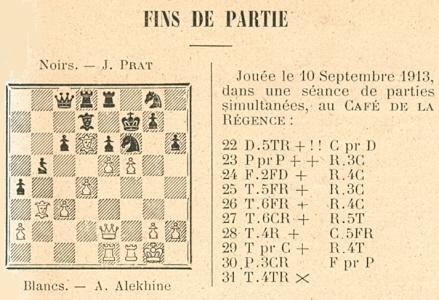

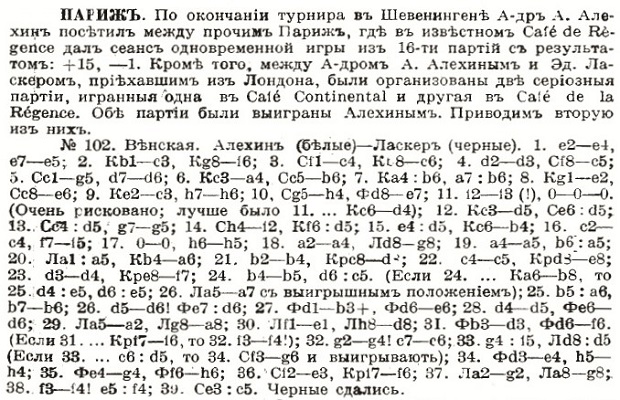

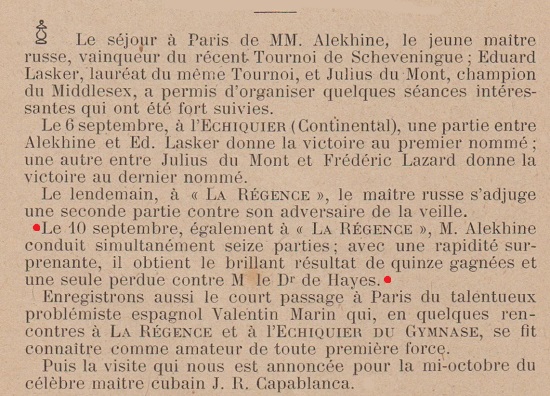

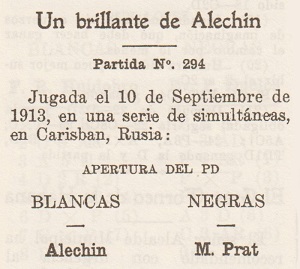

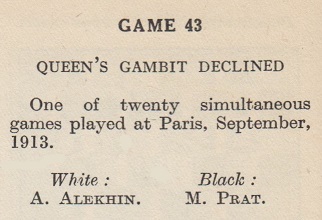

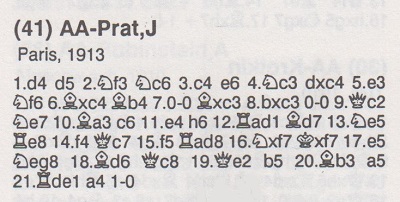

Game 43 in Alekhine’s first volume of Best Games, against ‘M. Prat’, was described as ‘one of 20 simultaneous games played at Paris, September 1913’. The book was published in 1927; the German and Dutch editions brought out in 1929 identified Black as ‘J. Prat’ and did not stipulate the number of games in the exhibition. On the other hand, Deux cents parties d’échecs (Rouen, 1936) said that it was a 20-board display and that Black was ‘N. Prat’.

La Stratégie (October 1913, page 415) gave only the conclusion of the game and did not offer corroboration of Alekhine’s later statement that after Black’s 21st move he announced mate in ten:

As regards the number of players, 16 was the figure specified on page 360 of the September 1913 issue of the French magazine:

‘Le 10 septembre, également à La Régence, M. Alekhine conduit simultanément seize parties; avec une rapidité surprenante, il obtient le brillant résultat de quinze gagnées et une seule perdue contre M. le Dr de Hayes.’

(7040)

White announced mate in ten: 22 Qh5+ Nxh5 23 fxe6+ Kg6 24 Bc2+ Kg5 25 Rf5+ Kg6 26 Rf6+ Kg5 27 Rg6+ Kh4 28 Re4+ Nf4 29 Rxf4+ Kh5 30 g3 any 31 Rh4 mate.

C.N. 7040 discussed discrepancies surrounding this famous Alekhine victory, and more are added now.

As regards Black’s identity, we have never seen a full name, but only ‘Prat’, with or without an initial. Our earlier item pointed out that in the English, German/Dutch and French editions of Alekhine’s first Best Games book the initial was given as M., J. and N. respectively. A fourth option, I., is in the Russian edition (Moscow and Leningrad, 1927). Although ‘M. Prat’ is the most common version, a misunderstanding may have arisen through M. being an abbreviation for Monsieur (as discussed, in another context, in C.N. 6693).

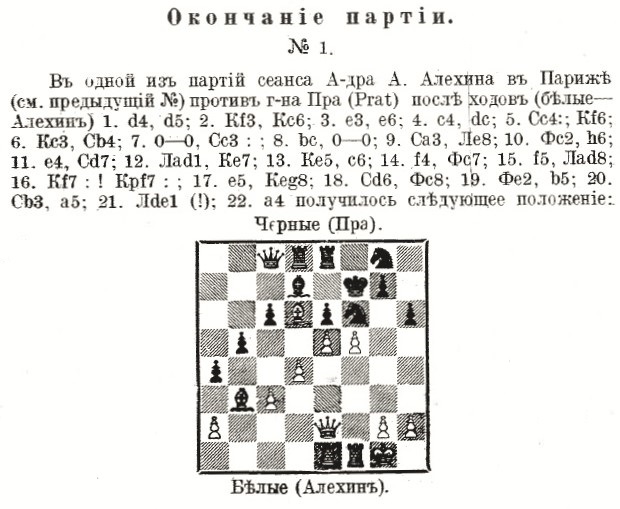

‘J. Prat’ was the name when the 22 Qh5+ finish was published on page 415 of La Stratégie, October 1913 (reproduced in C.N. 7040). The earliest occurrence of the full game-score that we can cite is on pages 286-287 of Shakhmatny Vestnik, 15 September 1913, shown here courtesy of the Royal Library in The Hague:

The heading stated that Alekhine played ‘against Mr Prat’; г-на is an abbreviation of the genitive singular form Господина (‘Mr’).

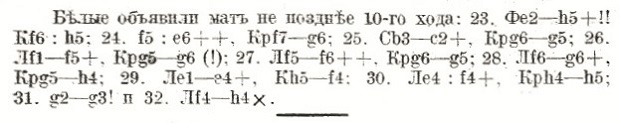

The Royal Library has also kindly provided the item on page 273 of the 1 September 1913 edition of Shakhmatny Vestnik to which the 15 September issue referred:

The report that Alekhine’s exhibition in Paris comprised 16 games (+15 –0 =1) corresponds to the information on page 360 of La Stratégie, September 1913:

As previously shown, page 415 of the October 1913 issue of La Stratégie also gave the date of the display as 10 September 1913. The fact that the above issue of Shakhmatny Vestnik was, formally at least, dated 1 September is not a stumbling-block, given the 13-day difference between the Julian and Gregorian calendars and the inclusion of Alekhine’s game against Edward Lasker, played on 7 September. It is, though, unclear why ‘August 1913’ was in the heading to the Prat game on page 119 of volume one of Complete Games of Alekhine by J. Kalendovský and V. Fiala (Olomouc, 1992). Page 87 of Alexander Alekhine’s Chess Games, 1902-1946 by L.M. Skinner and R.G.P. Verhoeven (Jefferson, 1998) put only ‘1913’ (and ‘J. Prat’), but the previous page duly referred to the 16-board display on 10 September 1913.

Although page 192 of Capablanca-Magazine, 15 November 1913 also dated the game ‘10 September 1913’, there was a mysterious assertion that it was played in ‘Carisban, Russia’:

The English and French editions of Alekhine’s first Best Games book stated that the simultaneous display consisted of 20 games, which contradicts the reports in Shakhmatny Vestnik and La Stratégie. Below are the headings in the various editions of Alekhine’s book, in chronological order of publication (London, 1927; Moscow and Leningrad, 1927; Berlin and Leipzig, 1929; The Hague, 1929; Rouen, 1936):

All these books recorded that the game began 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 dxc4 5 e3 Nf6 6 Bxc4, whereas Shakhmatny Vestnik and Capablanca-Magazine had 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 e3 e6 4 c4 dxc4 5 Bxc4 Nf6 6 Nc3. The latter order is not among the five versions of the game in FatBase 2000, although the CD included 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 dxc4 5 e3 Nc6 6 Bxc4.

The lengthiest coverage of Alekhine v Prat that we have seen is on pages 199-215 of How to Think Ahead in Chess by I.A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1951). The worst treatment is on page 308 of The Games of Alekhine by Rogelio Caparrós and Peter Lahde (Brentwood, 1992). Alekhine’s brilliant conclusion beginning with 22 Qh5+ was not even mentioned:

(10042)

James Stripes (Spokane, WA, USA) requests more information about the Taylor v N.N. game mentioned in C.N. 1371 and, in particular, about the identity of White. Firstly, we reproduce that item (which is on page 164 of Chess Explorations):

On page 30 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess Irving Chernev gives the queen odds game Potter v Amateur (London, 1870), in which ‘after only six moves were played, Potter announced a forced mate in nine!’ Chernev’s closing assertion: ‘Never before or since has a mate been announced which is longer than the rest of the game itself!’ See also page 75 of The Fireside Book of Chess for a similar remark.

Yet on page 2 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess the same Irving Chernev gives the score of Taylor v Amateur (London, 1862) in which, after Black’s fifth move, ‘White announced a forced mate in eight moves’. The game is introduced as follows: ‘The announcement of a forced win always comes as a shock to the victim. It is doubly so here, as the winning line of play is longer than the rest of the game itself!’ And on the following page he publishes the Potter game too.

Above is the position after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Bc4 Nxe4 4 Nc3 Nc5 5 Nxe5 f6 in the game Taylor v N.N.

White was I.O. Howard Taylor, who gave the diagrammed position on page 121 of his book Chess Brilliants (London, 1869) with the following text:

‘The diagram represents a quaint situation which happened to I.O.H.T. (White) on sitting down at the Philidorian Chess Rooms about February 1862, to play with a stranger (Black).

The fifth move only had been reached and the illustrious unknown had replied 5...P to KB’s 3rd. White thereupon mated in eight moves.’

The mating line, given by Taylor on page 128 (also without any reference to an announcement), corresponds to the moves in Chernev’s Best Short Games.

(7564)

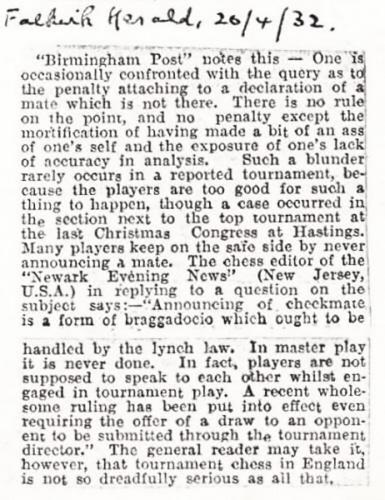

From Stephen Wright (Vancouver, Canada):

‘When and why did the practice of announcing mate in tournament and match games end?’

Is there unanimity today among administrators and officials on the procedure applicable if a player announces mate during a game (and, additionally, in case of an incorrect announcement)? Information will also be welcomed on the most recent games to contain mate announcements. Have there been many significant specimens since Marshall v Bogoljubow, New York, 1924, in which White announced mate in five moves at move 38?

A cutting from page 1 of an untitled scrapbook produced by Dale Brandreth:

The Factfinder refers to a number of older examples of announced mates, and one case of an announced stalemate.

(8329)

From Geurt Gijssen (Nijmegen, the Netherlands):

‘For more than 30 years I have worked as a chess arbiter, and it has never happened that a player announced checkmate in x moves.

If it did occur, I would apply Article 12.6 of the current Laws of Chess:

“It is forbidden to distract or annoy the opponent in any manner whatsoever. This includes unreasonable claims, unreasonable offers of a draw or the introduction of a source of noise into the playing area.”

The player can be given a warning, but I would also be inclined to add some extra time to the opponent’s thinking time, and especially if any such remark were made when the opponent was short of time.

In my opinion, announcing checkmate in a certain number of moves is annoying, distracting and also intimidating for the opponent, and it is therefore forbidden.’

(8334)

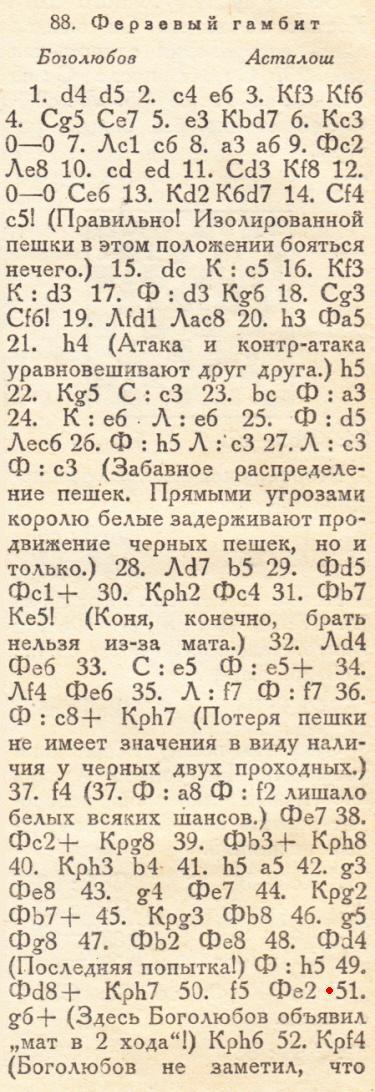

Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA) recalls the report in the Bled, 1931 tournament book by Hans Kmoch that Bogoljubow announced a non-existent mate in two against Asztalos:

Bogoljubow overlooked that after 51 g6+ Kh6 there could occur 52 Qh8+ Kg5 or 52 Qh4+ Qh5.

From pages 110-111 of Kmoch’s tournament book, published in 1934:

The relevant text is on page 121 of Bled 1931 International Chess Tournament translated by Jimmy Adams (Yorklyn, 1987).

Mr Wrinn also mentions that the English edition includes an article by Salo Flohr, translated from a 1976 issue of 64, which refers to the announced mate (on pages xi-xii). See too page 29 of the March 2003 CHESS, in which issue the full Flohr article was reprinted.

(8351)

Wanted: early examples of announced mates, as well as information on how the practice began and developed.

(8360)

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) writes:

‘Pages 71-74 of the November 1880 Chess Monthly have an article by Alphonse Delannoy, and page 74 describes an encounter between Labourdonnais and Mouret where the former announced mate in five moves in the final game of a series in which the stakes escalated dramatically. Labourdonnais offered a knight sacrifice, which Mouret accepted. Then Labourdonnais said, in Delannoy’s account: “Well, sir, you have lost the game. You are mated in five moves.”

It is stated that this occurred before Labourdonnais had directly challenged Deschapelles, and therefore presumably before their 1821 contest involving Cochrane as well, but after Mouret had been on a tour as director of the Turk. This places the event around 1820, though possibly a year earlier or later.’

(8367)

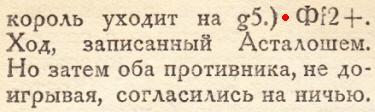

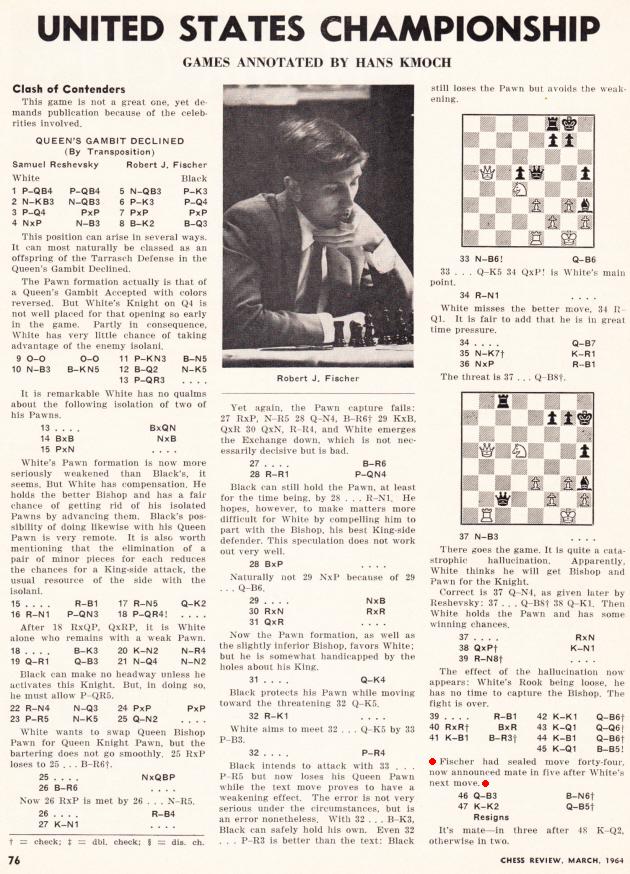

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) draws attention to comments by Hans Kmoch on page 76 of the March 1964 Chess Review (Reshevsky v Fischer, 1963-64 US championship):

(8381)

Richard Hervert (Aberdeen, MD, USA) asks whether anything further can be found about the announcement of an alleged mate-in-ten first discussed in C.N. 1857. See page 83 of Chess Explorations, as well as pages 29-30 of A Chess Omnibus and a Chess Explorations article of ours at ChessBase.com dated 31 May 2008.

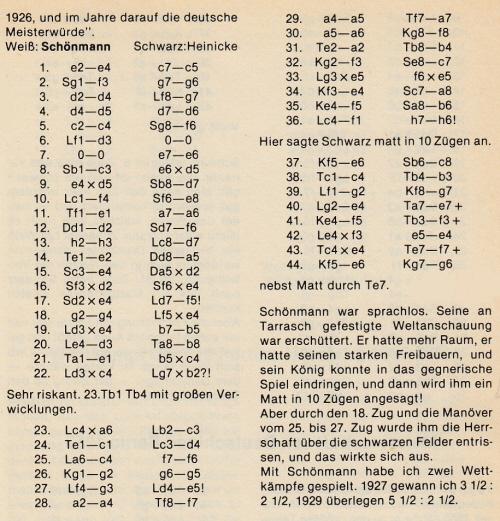

Below is the game as it appeared in our source, page 65 of Kunst des Positionsspiels by Herbert Heinicke (Hamburg, 1981):

Position before 36...h6

The latest computer check still suggests that there is no clear mate. Black wins in all lines, and 37 Kg6 offers more resistance than 37 Ke6.

(8571)

Pages 253-254 of the September 1875 City of London Chess Magazine gave, with ‘notes by A. Burn, Jun.’, the well-known Gilbert v Berry game (1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Nxe4 6 Re1 Nc5 7 Bxc6 dxc6 8 d4 Ne6 9 dxe5 Qe7 10 Nc3 Bd7 11 a4 O-O-O 12 b3 f6 13 Qe2 Qf7 14 Ne4 Rg8 15 c3 h6 16 b4 f5 17 Ng3 g5 18 Nd4 Nxd4 19 cxd4 Re8 20 b5 cxb5 21 axb5 Bxb5 22 e6 Qg6 23 Qxb5 f4 ‘and White announced mate in 19 moves’) courtesy of the Hartford Times. The game prompted some general comments on women’s chess on pages 227-228 of the same issue of Potter’s magazine:

‘We present this month a correspondence game – taken by us from the Hartford Times – between Mrs Gilbert, of Hartford, Connecticut, the strongest lady player in the United States, and Mr Berry, of Beverly, Massachusetts, in which the former announces a mate in 19 moves. The immeasurable superiority of trousers chess is often vaunted, and the natural incapability of women for excellence in the game is deduced from certain propositions, any one of which is a fact taken for granted, though neither self-evident nor demonstrable. The strength of men’s prejudices and of their boot-holding extremities are [sic] generally about on a par, and very often they cooperate. Their physical superiority they use first as a force, and then as an argument. Excluding the ladies by the rule of fist from clubs and associations, discouraging their home play, and pooh-poohing their first timid efforts, the masculine countenance then lights up with an idiotic grin which seconds the enunciation. “Women play? Can’t do it, sir; Nature wills otherwise. Let them cook and sew, that’s what they can do, sir.” Very much would we like to get hold of one of these oracles, place before him the position in which Mrs Gilbert announced “checkmate in 19 moves”, and ask him to find out how it was to be done. If, moreover, we could extract from him a pledge that he would not dine until he had solved it, then our cup of happiness would be overflowing, for we should have delicious visions of many dinnerless days as the just punishment of irrational prejudication. There is this further to be said, that to study a position when you are told there is a mate in 19 moves is quite a different thing from conceiving the idea of it in the first instance, and then working up the possibility into a certainty. Mrs Gilbert says that it was one of the severest intellectual tasks she ever attempted. We have no doubt of it, especially in a case like the present, where the defence is not forced to a particular line of play. The human mind with difficulty grasps such a succession of sequences, even with the solution given, and such an achievement in one of the depreciated female sex ought to have two effects – shake the prejudices of men and create self-confidence in women. We should like to see chess become more general among the latter. Why should it not be a common thing for a man and wife to have a game before going to rest? Much more companionable and reasonable, we should say, than the one soaking his brains with numerous nightcaps, while the other spends a listless half-hour unpinning her back hair and counting her spoons.’

(9898)

‘A novel prize is offered by a member of the Manhattan Chess Club to the competitors in the club championship tourney. The prize is to be awarded “for the best long-distance mate or, in other words, to that player who shall announce mate the furthest number of moves ahead”.’

Source: Lasker’s Chess Magazine, December 1904, page 59.

(10301)

Zachary Saine (Amsterdam) asks how the practice of announced mates arose.

(11973)

We are grateful to Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) for making an initial search for early references to announced mates. It may seem logical to assume that correspondence chess gave an impetus to the practice, to limit postage outlay, but hard facts are still lacking.

Our correspondent draws attention to page 220 of Volume II of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, which includes this:

‘M. Chamouillet here announced that he could force mate in nine moves; and his adversaries, after examining the position, resigned.’

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘Page 23 of William Hartston’s The Kings of Chess (London, 1985) contains an example of an announced mate by Philidor. The occasion was an odds game with Count Brühl at Parsloe’s in London on 26 January 1789. White was in check, “and Philidor announced mate in two moves: 28 Qxf5! and 29 Rh8 mate”.

George Walker’s A Selection of Games at Chess, actually played by Philidor and his contemporaries (London, 1835) includes the game on pages 41-42 with the following termination:

“27 K. Kt. P. on. Kt. to K. B. fourth, ch. 28 Q takes Kt., and Mates next move with R.”

The Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games by Levy and O’Connell (Oxford, 1981) has the score (page 15) as concluding with “27 g5 Nf5+ 1-0” and gives the source as “MS H.J. Murray 64, Bodleian Oxford, ‘Collection of European Games’”.’

(12014)

***

Below is a rare instance of an announced stalemate:

E. Delmar-S.M.B., Skaneateles, August 1892

Black played 1…Rxh3 and after 2 g5 Rg3 Delmar ‘announced stalemate in four [sic] moves’.

Source: American Chess Monthly, October 1892, page 210.

(2544)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.