C.N. 8062

Edward Winter

C.N. 8062

In an article on pages 364-365 of the December 1956 Chess Review Bruce Hayden wrote:

‘But imagine my surprise when I asked the great old warrior [Bernstein] who was his favorite among the players of the past. “James Mason”, he replied, “Not because he was the strongest but because he played my two favourite combinations”.’

The item was reprinted on pages 116-120 of Hayden’s book Cabbage Heads and Chess Kings (London, 1960). The two combinations occurred in Mason v Winawer, Vienna, 1882 and Mason v Janowsky, Monte Carlo, 1902. Both games can be found in an article on Mason by Jim Hayes on pages 10-15 of the March 1997 CHESS ...

(Chess Café, 1998)

We wonder whether any readers have seen the writings of Ossip Bernstein described in this paragraph from page 118 of the April 1950 BCM:

‘During the last year the European edition of the New York Herald has been running a most valuable weekly column written by the famous master, Dr O. Bernstein. It contains annotated games, news, endgame studies, etc. What makes it valuable is the original approach Dr Bernstein shows towards the games and the consequent discoveries he has been able to make of lines overlooked, not only by the players themselves, but by all other annotators.’

(2609)

‘Dr Bernstein is a famous master; his fame rests on three atrociously played games with Capablanca. That this great player deserves more than merely negative immortality is realized by very few people. Tartakower points out the interesting fact that Bernstein, in common with Rubinstein, Nimzowitsch and Spielmann, was among the first to rebel against the artificial stiffness and formalism of the Tarrasch epoch.’

Source: Page 36 of Chess Strategy and Tactics by F. Reinfeld and I. Chernev (New York, 1933).

(2692)

Our feature article Warriors of the Mind mentions that book’s faulty totals of Capablanca v Bernstein games.

From page 312 of the July 1961 CHESS:

‘Paul H. Little, San Francisco, asks can any reader supply him with the score of the 1914 St Petersburg Tourney game in which Capablanca beat Bernstein, obtaining a brilliancy prize.’

Little was an experienced chess writer, and it is strange indeed to see him appealing for the moves of one of the most famous games ever played.

(2963)

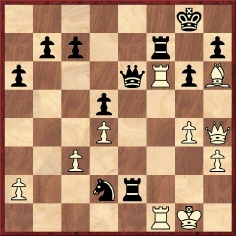

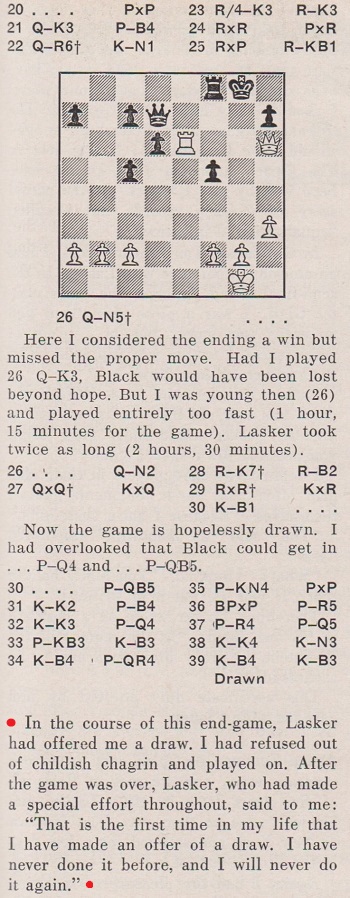

This brief feature by Ossip Bernstein was published on page 726 of the September 1927 issue of L’Echiquier:

‘Some time ago I was at the Gambit Café in London. Watching the games being played before me, I saw among others the following position, which occurred in a game between two strong players:

The game is obviously lost for White, but in desperation he continued to play automatically: 1 Nd7. Black replied 1…e2?, and White resigned, as he played 2 Bxe2, at the point when he could draw the game with the following combination which I showed him: 2 Nxe5! (instead of 2 Bxe2) 2…e1(Q) 3 Rf8+!! Rxf8 (If 3…Kh7? White mates in two moves.) 4 Ng6+, followed by perpetual check.’

(3074)

The following appeared on page 189 of the July 1941 BCM:

‘News is to hand that Dr O. Bernstein, one of the great figures in chess, who was resident in France for the last 20 years, has been interned in unoccupied France, apparently solely for “racial reasons”.’

(3106)

C.N. 744 referred to L. Pachman’s remark on page 56 of his book The Opening Game in Chess (London, 1982) that after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 the reply 3…Nxe4, long considered a blunder, can be turned into ‘a gambit which is not without chances’. Below is a miniature in which the line was unsuccessful:

Alexander Steinkühler – Bernhard Horwitz

Manchester (date?)

Petroff Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 Nxe4 4 Qe2 Qe7 5 Qxe4 d6 6 d4 Nd7 7 f4 f6 8 Be2 fxe5 9 fxe5 dxe5 10 O-O exd4 11 Bh5+ Kd8 12 Bg5 Nf6 13 Rxf6 Qxe4 14 Rd6 mate.

Source: the Chess Player’s Magazine, 1863, page 125.

A very similar game (won by Ossip Bernstein at queen’s rook odds in Paris, 1931 against an unnamed opponent) was published on, for instance, pages 111-112 of Chernev’s 1000 Best Short Games of Chess:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 Nxe4 4 Qe2 Qe7 5 Qxe4 d6 6 d4 f6 7 f4 Nd7 8 Bc4 fxe5 9 fxe5 dxe5 10 O-O exd4 11 Bf7+ Kd8 12 Bg5 Nf6 13 Rxf6 Qxe4 14 Rd6 mate.

(3275)

On page 279 of The Chess Companion (New York, 1968 and London, 1970) I. Chernev attributed the following to Tartakower:

‘The great master places a knight at K5; checkmate follows by itself.’

As was pointed out in C.N. 2194 (see pages 338-339 of A Chess Omnibus), Tartakower merely quoted an onlooker at a game won by O. Bernstein in Paris in 1933. On page 426 of L’Echiquier, 17 February 1934 Tartakower wrote:

‘“Ces grands-maîtres placent leur[s] Cavaliers à é5 et après les mats découlent d’eux-mêmes!” dit en voyant cette catastrophe un spectateur grincheux.’

(3514)

For further citations, see A Knight on K5, K6 or Q6.

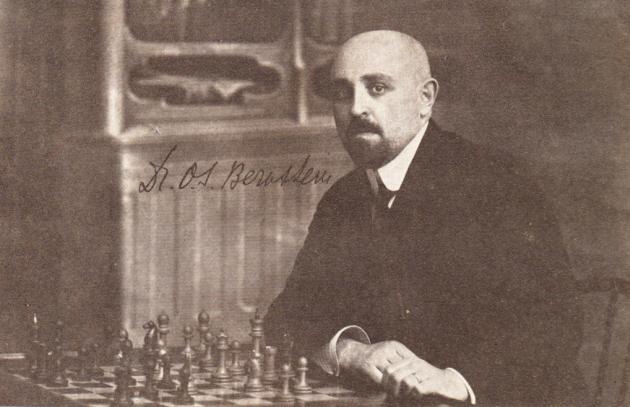

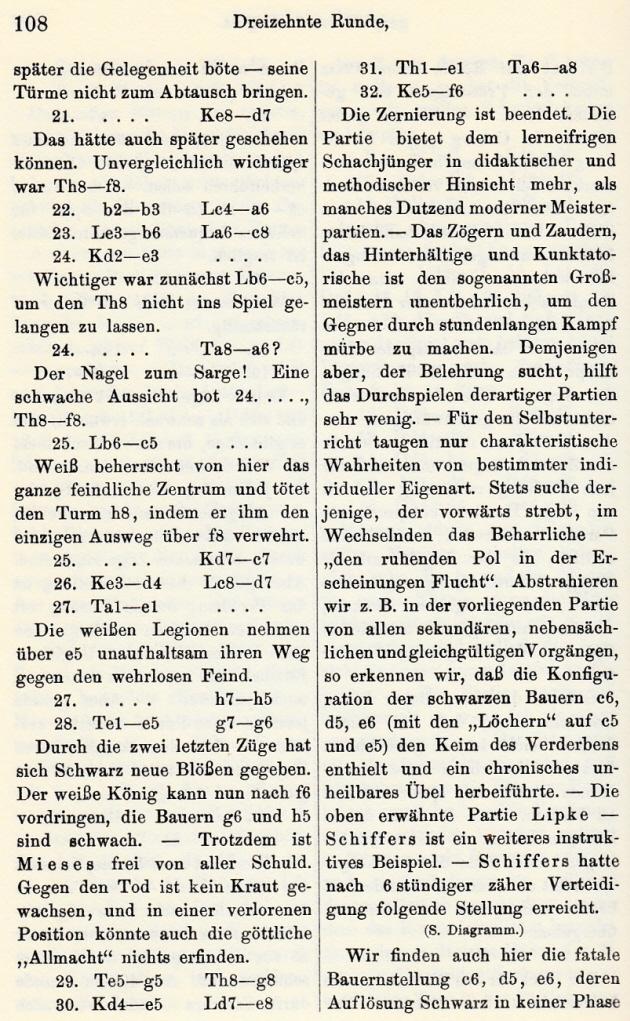

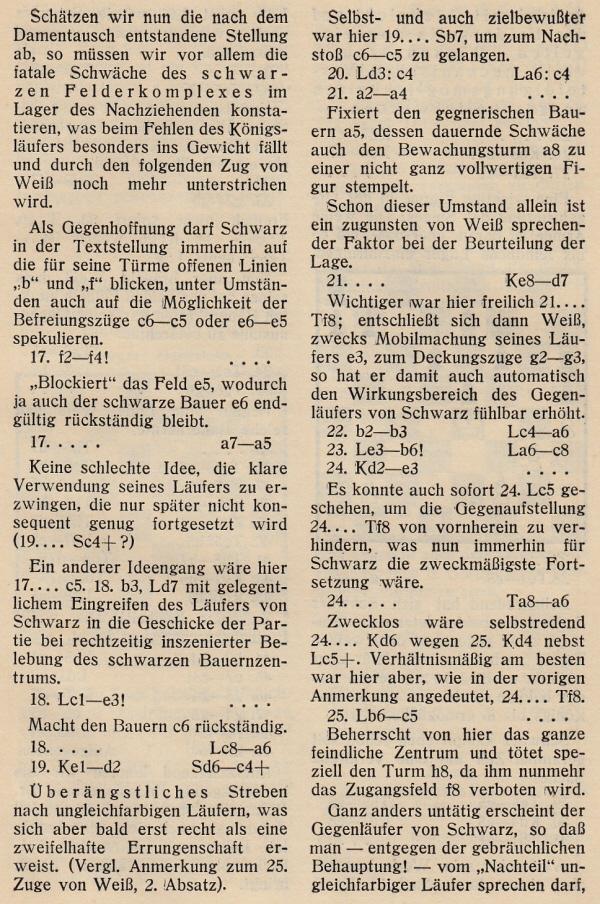

A group photograph taken at Coburg, 1904:

Standing (left to right): C.

Schlechter, H. Ranneforth, R. Swiderski, C. Schröder, A. Schott,

F. Tausch, W. John, H. Süchting, C. Teller, L. Fleischmann.

Seated: J. Mieses, H. Wolf, H. von Gottschall, P. Schellenberg,

R. Gebhardt, J. Berger, G. Marco, O. Bernstein, C. von

Bardeleben, H. Caro.

(3570)

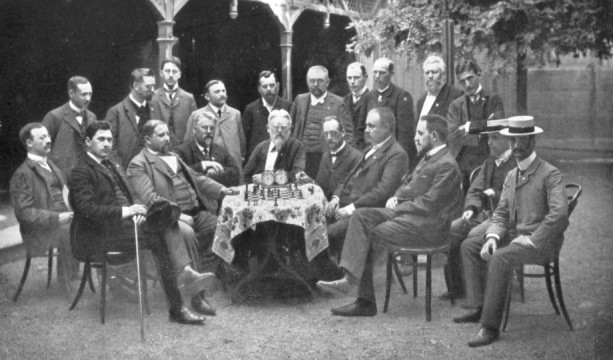

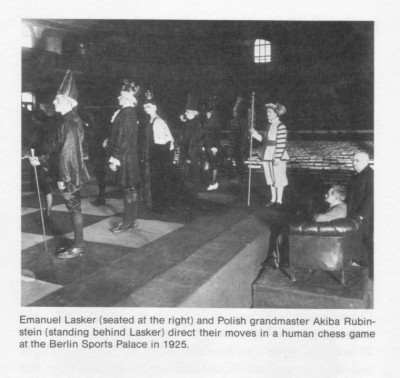

This illustration appears on page 22 of Famous Chess Players by Peter Morris Lerner (Minneapolis, 1973):

The date 1925 is an error for 1924, but we also suggest that the person on the far right is not Akiba Rubinstein but, probably, Ossip Bernstein. The latter participated in the event, as reported on page 300 of the October 1924 Wiener Schachzeitung.

(3775)

A remark about Bernstein from page 140 of Chess World, 1 August 1946:

‘His chess has perhaps taken a new lease of life since the death of Capablanca, who was the only player that could win brilliancies from Bernstein and nearly always did so.’

Hardly an observation to be taken seriously, of course, and not least because the final game between Bernstein and Capablanca was back in 1914.

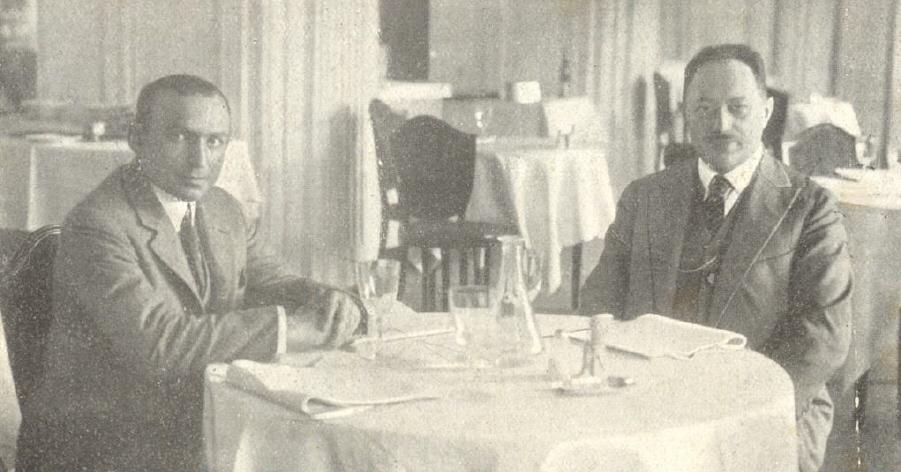

Left to right: M. Vidmar, O. Bernstein and S. Tartakower (Groningen, 1946)

(3966)

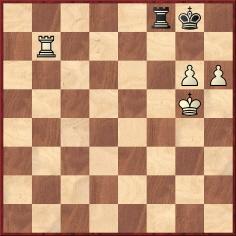

This position, with Black to move, is from a game won by Ossip Bernstein against an unnamed player in Paris, 1959:

Black won with 1...Qd6 2 R6f2 Nf3+ 3 Kh1 Qh2+ 4 Rxh2 Rxh2 mate.

Source: Schach-Echo, 5 March 1960, page 73. Is the full game-score extant?

(4526)

A gap in chess records concerns the place of death of Ossip Bernstein. Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (1987 and 1994 editions) cautiously indicated only the country, France. In the first paragraph of his obituary on pages 72-74 of the March 1963 BCM Harry Golombek reported that Bernstein had died at a health resort (unnamed) in the French Pyrenees, while on pages 104-105 of the April 1963 Chess Review Edward Lasker wrote:

‘The last year of his life, Bernstein spent in St Arroman, a small quiet place in the Pyrenees, near his beloved Spain, to get away from the hustle and bustle of Paris which began to be too strenuous for him. He died in his sleep last 30 November, the day he was taken to a hospital for treatment of his weakening heart.’

What is required, of course, is information from a contemporary local source. Can a reader find out anything?

Ossip Bernstein

(4579)

In the Capablanca entry on page 64 of The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks (London, 1970) – and on page 75 of the second edition (1976) – David Hooper wrote:

‘As predicted by Bernstein and others who knew Alekhine well, there was no return match.’

What more is known about the predictions of Bernstein and ‘others’?

(4649)

C.N. 3620 gave this photograph of Jacob Bernstein (left) and Oscar Chajes, which was the frontispiece of the Carlsbad, 1923 tournament book:

In a number of places (not only on the Internet but also, for instance, on page 23 of the San Sebastián, 1911 tournament book mentioned in C.N. 4741) the left-hand part of the photograph is used as an illustration of Ossip Bernstein.

(4796)

See too Chess: Mistaken Identity.

Mention is also made here of our feature article on Sidney N. Bernstein.

An extract from the entry dated 7 April 1914 (old style calendar) in S. Prokofiev’s diary, regarding the St Petersburg tournament:

‘Bernstein, a prosperous-looking man with a handsome, impudent face, shaven head and a colossal nose, dazzling teeth and relentlessly brilliant eyes.’

(4925)

C.N. 4239 gave this description of Bernstein by Edward Lasker:

‘I turned to the man in surprise and was struck by his extraordinarily good looks. He was about six foot three, slim as a young tree, and very handsome with black hair, a high forehead and large shining eyes. I asked him who he was; and, when he introduced himself as Ossip Bernstein, I was overawed.’

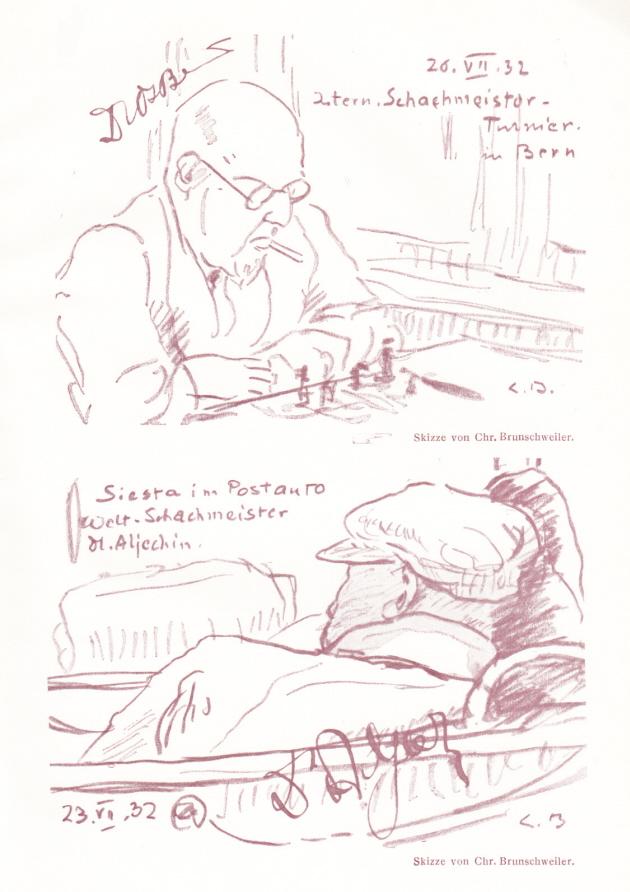

These sketches by Chr. Brunschweiler appeared in the Berne, 1932 tournament book.

(5054)

A sketch of Bernstein by David Friedmann in the portfolio ‘Köpfe berühmter Schachmeister’ was mentioned in C.N. 4132. See Chess Cartoons and Caricatures.

Ossip Bernstein gave the following assessment of Dawid Janowsky on page 15 of the January 1956 Chess Review:

‘Janowsky was no chess scientist or theoretician. He knew what he had to do on the chessboard; but he did not know, or could not explain, why it had to be done. He had only two rules in chess: always attack; always get the two bishops (and, indeed, he used the advantage of the two bishops wonderfully). His main strength, indeed, was his extraordinary intuition, which gave him the exact feeling for what to do and how to do it.’

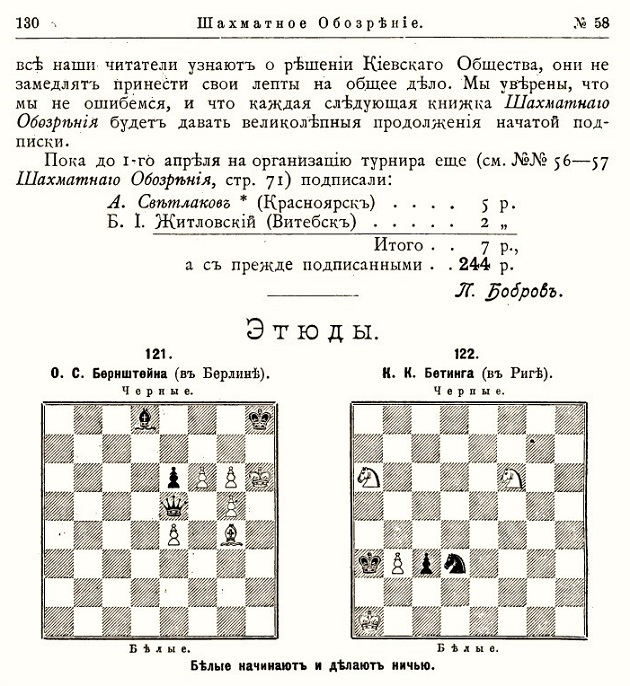

As stated on page 39 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, the position below was given on page 108 of Creative Chess by Amatzia Avni (1991 and 1997 editions) with the heading ‘Dr O. Bernstein-Amateur, Stockholm, 1906’:

In this seemingly hopeless situation White was said to have drawn with 1 Rgd6 (If 1 Ra7 d2 2 Rgxg7 Rg8 and Black wins.) 1...d2 2 Rac6 Rb8 3 Rb6 Ra8 4 Ra6, but we pointed out that when the position appeared on page 1610 of L’Echiquier of 9 April 1932 it was given as a study, published in ‘Chakmatnoe Obozzenic 1906’ (i.e. Shakmatnoe Obozrenie).

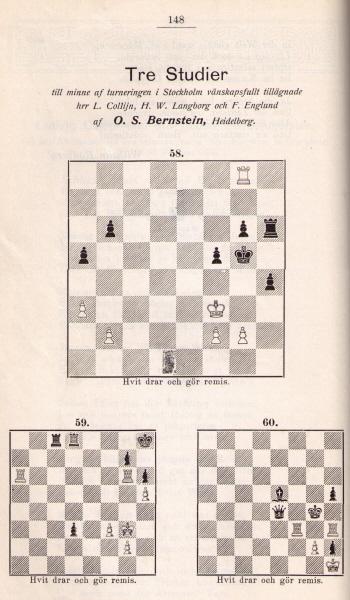

Now René Olthof (’s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands) mentions, on the basis of information from Harold van der Heijden, that it was a composition published on page 148 of the 4/5 1906 issue of the Swedish magazine Tidskrift för Schack, being one of three studies by Bernstein dedicated to Ludvig Collijn, Hugo W. Langborg and Fritz Englund. The same information has been supplied by Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden), who gives the page in question:

(5220)

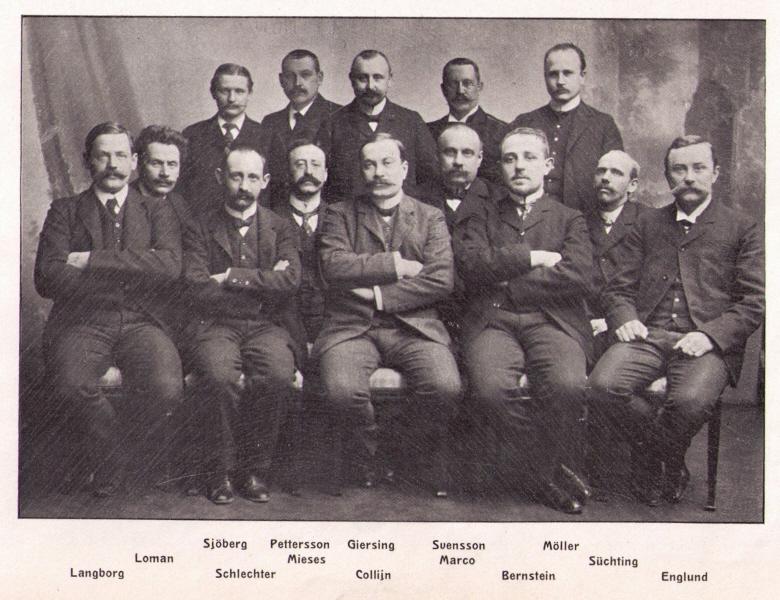

Calle Erlandsson sends this group photograph taken during the Stockholm, 1906 tournament, from that year’s Tidskrift för Schack (between page 56 of issue 3 and page 57 of issue 4/5):

(5221)

From Henk Smout (Leiden, the Netherlands), further to C.N.s 6370 and 6384:

‘In this first-round photograph (also published opposite page 32 of the book 20 grote denkers binnen Neêrlands grenzen by Peter van Foreest) the master furthest away in the left-hand row is Smyslov, playing against Vidmar. Then come Steiner, Botvinnik, Denker and (in the foreground with his back to the camera) Guimard. In the right-hand row, the first (front) master is Christoffel (back to camera), in play against O’Kelly. At the next board is Kottnauer, playing against Bernstein. Then come Yanofsky, Kotov at the board with Stoltz and, finally, Flohr. Standing behind Flohr seems to be Tartakower and behind him, on the left, Kmoch. Standing behind Botvinnik’s board, with his hands in his pockets, is Najdorf, and behind him is Euwe. Between the boards of Botvinnik and Denker, Lundin is standing on the left, and Szabó on the right. That leaves Boleslavsky. He is to the right of Najdorf and behind Szabó.

The second photograph, taken before the start of the fourth round, was given opposite page 80 of van Foreest’s book, which mentions all the names. Seated, from the left: Najdorf, Flohr, Euwe, Vidmar, Bernstein, Tartakower, Guimard and Yanofsky. Standing, from the left: Smyslov, O’Kelly, Boleslavsky, Steiner, Botvinnik, Kotov, Szabó, Kottnauer, Denker, Lundin, Stoltz, Christoffel and Kmoch.’

In the first photograph Guy Brunet (Montreal, Canada) suggests that the figure on the left watching Botvinnik’s game is Alexander Rueb.

(6425)

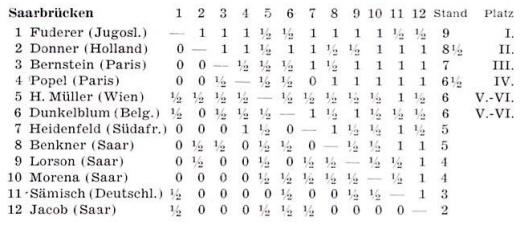

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) sends two photographs from pages 48-49 of the 2/1954 issue of FIDE Revue:

Page 48 gave the crosstable:

(6467)

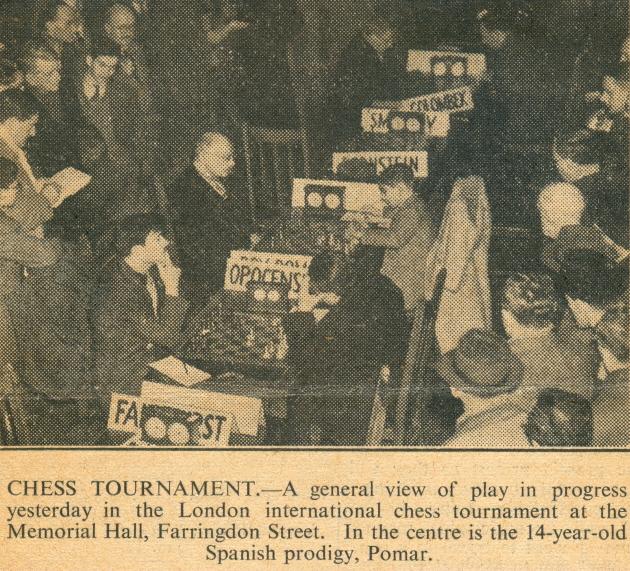

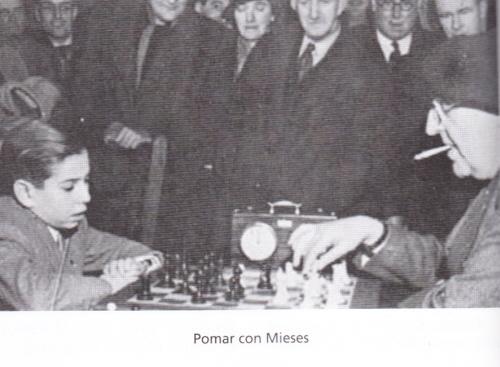

We recall three photographs of Arturo Pomar in play against Ossip Bernstein at London, 1946:

Sources: CHESS, February 1946, page 96; London, 1946 (Sutton Coldfield, 1946), page 10

Source: La vida de Arturito Pomar by J.M. Fuentes and J. Ganzo (Madrid, 1946), opposite page 224

Source: The Encyclopedia of Chess by H. Golombek (London, 1977), page 28

However, in every source (including the above-mentioned tournament book and the volume on the event edited by E.G.R. Cordingley, as well as the The Times, the BCM and CHESS) where round-by-round reports and/or the game-score have been found it is stated that Pomar had the white pieces against Bernstein (the moves being 1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e3 h6 6 Bh4 Ne4 7 Bxe7 Qxe7 8 cxd5 Nxc3 9 bxc3 exd5 10 Qb3 Qd6 11 Nf3 O-O 12 c4 dxc4 13 Bxc4 Nc6 14 O-O Na5 15 Qc3 Nxc4 16 Qxc4 Be6 17 Qb5 Bd5 18 Ne5 b6 19 Rfc1 c5 20 f4 cxd4 21 Rd1 Rfc8 22 Rxd4 Rc5 23 Qd3 Qe6 24 Rd1 Bxa2 25 Rd8+ Rxd8 26 Qxd8+ Kh7 27 Nd7 Qxe3+ 28 Kh1 Drawn).

When was the photographed game played?

(6573)

Leonard Barden (London) wonders whether the three Pomar v Bernstein photographs in C.N. 6573 were taken shortly before the London, 1946 tournament, to promote media interest:

‘In the third photograph the spectator standing one from the right is G.H. White, the leader of the consortium including G. Wood and B.H. Wood which bought out Edith Price from the Gambit Chess Rooms. The man clutching the chair with only the lower half of his face visible looks like Walter Veitch, who was a regular player at the Gambit.’

For purposes of comparison, below is a photograph of the first day’s play in the London tournament, published on page 6 of The Times, 15 January 1946:

The newspaper’s report began:

‘An unfortunate hitch has occurred in the London chess tournament. The long expected Russian players have failed to turn up, and the players against whom they were paired awaited them in vain.’

The name-cards show that Smyslov was one of those expected and that he was scheduled to play Bernstein.

(6584)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) reports that the third Pomar v Bernstein photograph in C.N. 6573 was published on page 42 of ABC, 20 January 1946. There was a picture credit to ‘Ortiz’.

He also draws attention to page 2 of El Mundo Deportivo, 24 January 1946, which mentioned that a photograph of Pomar in play against Bernstein had been published in the New York Times.

We have found that picture (the second one in C.N. 6573) on page 35 of the sports section of the New York Times, 22 January 1946. The (faulty) caption was: ‘Arturito Pomar of Madrid during his match with Dr O.S. Bernstein of Paris at international event in London. The young Spaniard and his opponent played to a draw.’

(6609)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) notes a Pathé news item on the London, 1946 tournament, featuring Arturo Pomar in play (with the black pieces, as in the photograph above) against Ossip Bernstein, as well as footage of some other players, including Savielly Tartakower (briefly) and William Winter. The technical quality is good, with a commentary which is quintessentially English.

(6978)

A case of misidentification concerning the Pomar v Bernstein photograph given in C.N. 6573 occurs on page 68 of Arturo Pomar. Una vida dedicada al ajedrez by Antonio López Manzano and Joan Segura Vila (Badalona, 2009):

(7792)

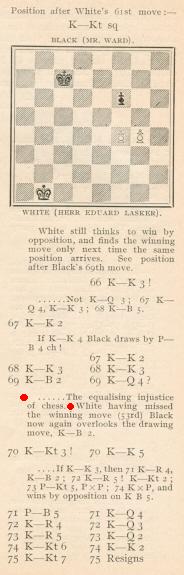

From an annotation on page 156 of the May 1961 Chess Review, in the magazine’s postal section (conducted by Jack Straley Battell):

‘... or, in the more erudite language of Dr Tartakower, “The equalizing injustice of chess”.’

A passage on page 251 of The Chess Masters on Winning Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1960):

‘... Bernstein made a point of what he called “the equalizing injustice of chess”. By this he meant, presumably, that the apparent unfairness of such a loss is canceled by a sequence of blunders: the player who finally pays for a mistake has probably escaped punishment for earlier mistakes. In the long run, undeserved victories will balance out with undeserved losses. (Of course, the term “undeserved” raises problems, for a mistake deserves to be punished.)’

It is indeed to Bernstein that the phrase is usually ascribed. See, for instance, pages 178-179 of Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood (Philadelphia, 1942) and pages 75 and 94 of Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters (New York, 1951), to mention two books by Edward Lasker.

Even so, the earliest citation that we can offer at present is from Edward Lasker himself (with no reference to Bernstein), in his annotations to a game on page 301 of the July 1913 BCM:

(6912)

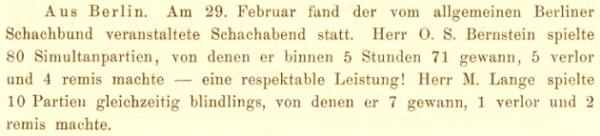

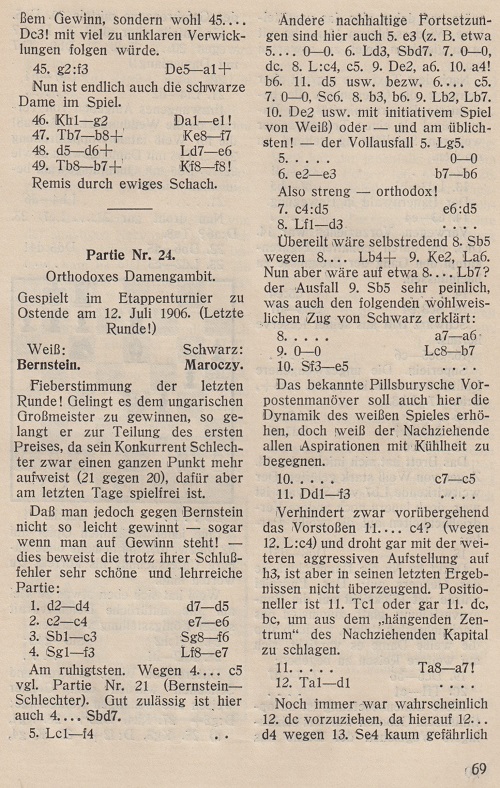

Our Large Simultaneous Displays feature article has a reference to Ossip Bernstein, and further details are added now. On page 8 of his monograph on Bernstein, Moderne Schachstrategie (Breslau, 1930), Tartakower wrote:

‘Bekanntlich war Dr Bernstein von jeher einer der besten und schnellsten Simultanspieler, da er bereits im Jahre 1903 in Berlin mit 80 innerhalb von 5½ Stunden durchgeführten Simultanpartien (Resultat. +70 –4 =6) eine Rekordleistung vollbrachte.’

The correct year would appear to be 1904, a different set of details being given on page 91 of the March 1904 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

(6965)

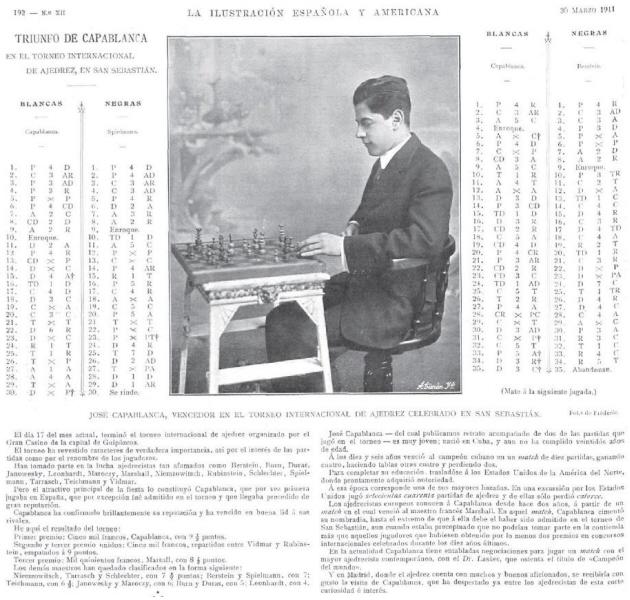

From Manuel Fernández Díaz (Estepa, Spain) comes this photograph of Capablanca which appeared on page 192 of the Madrid publication La Ilustración Española y Americana, 30 March 1911:

Readers are invited to examine closely the board set-up.

(7582)

When submitting the photograph of Capablanca given in C.N. 7582, Manuel Fernández Díaz noted that, despite appearances, the board position does correspond to an actual game, i.e. Capablanca v Ossip Bernstein, with 24 Rc1 being played. Marcelo Sibille (Montevideo, Uruguay) has also mentioned this to us.

Below is the full column (with many factual errors) on page 192 of La Ilustración Española y Americana, 30 March 1911:

(7587)

From page 32 of our 1989 monograph on Capablanca:

That Bernstein was against the Cuban’s participation only added to the drama of the final result – a clear first prize for the Cuban. Pablo Morán recounted on pages 22-23 of Los niños prodigio del ajedrez (Barcelona, 1973) that in Madrid in 1951 he asked Bernstein whether he had indeed objected to Capablanca’s entry. Bernstein looked at him slyly and replied: ‘There is a great deal of fantasy in everything that is said about that.’ Not exactly an admission, but not exactly a denial.

See also San Sebastián, 1911.

Stéphane Krebs (Cafquefou, France) draws attention to the genealogie.com website:

‘Ossip Bernstein

Naturalisation

Numéro de décret: 3057-33

Sujet: Bernstein Ossip

Naissance: le 20 septembre 1882 à Jitomir (Russie)

Lieu de l’acte: France

Date de l’acte: le 15 mars 1933.’

(8059)

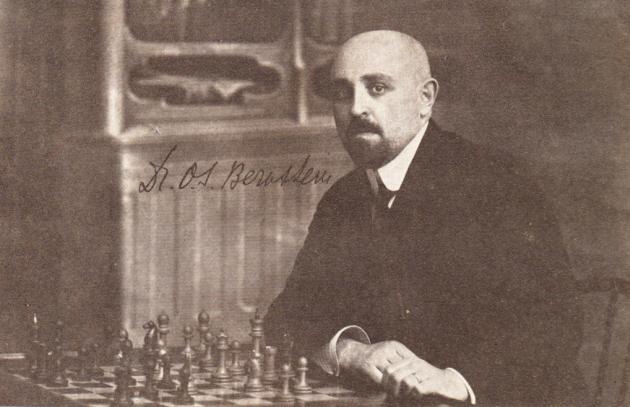

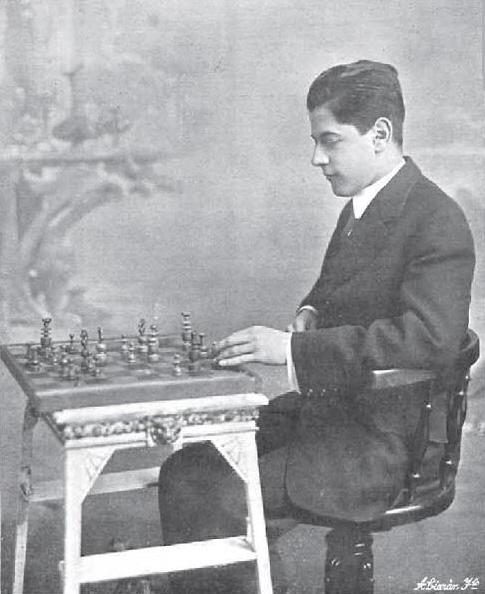

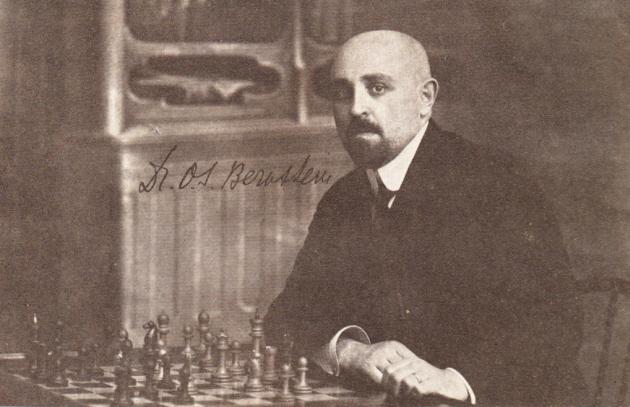

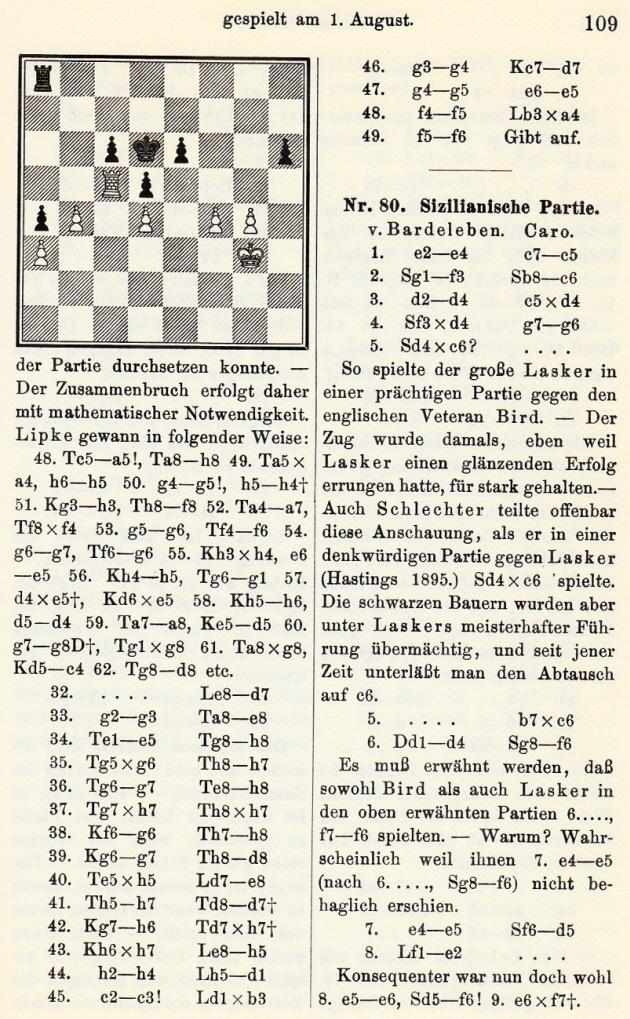

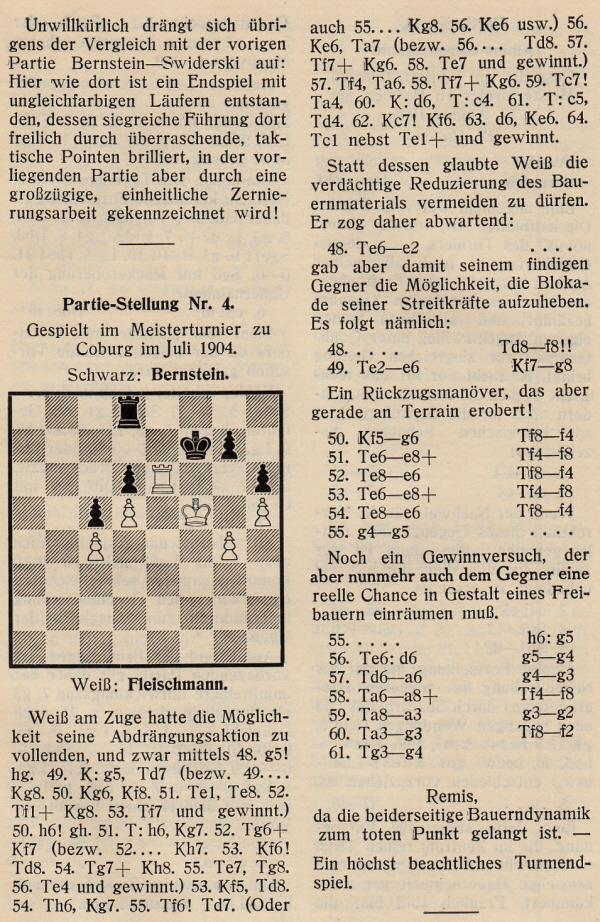

This photograph of Ossip Bernstein was the frontispiece to the monograph on him by Savielly Tartakower, Moderne Schachstrategie (Breslau, 1930):

(8062)

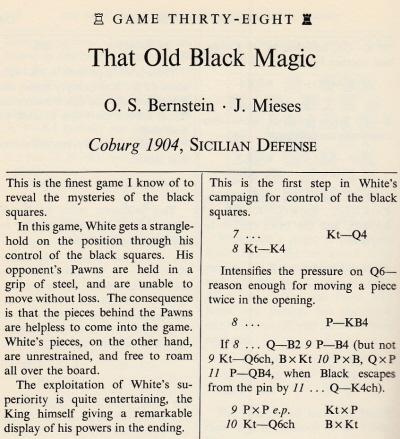

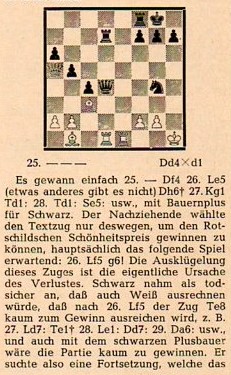

From page 160 of The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played by Irving Chernev (New York, 1965):

In his annotations to the game (pages 160-165) Chernev did not indicate explicitly which move or moves caused Black’s defeat. See too his notes in Logical Chess Move by Move (New York, 1957).

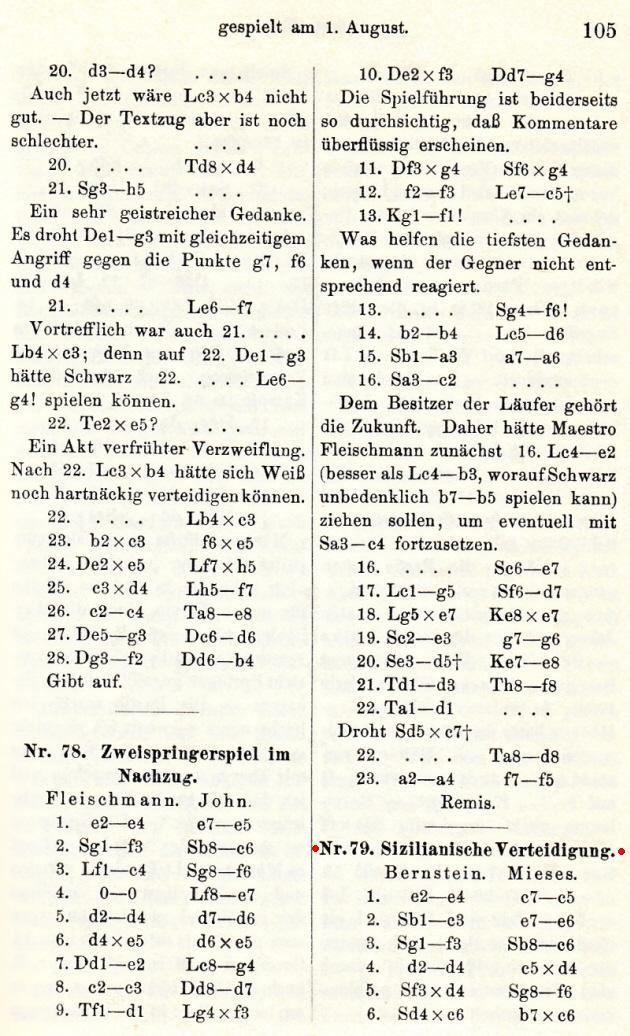

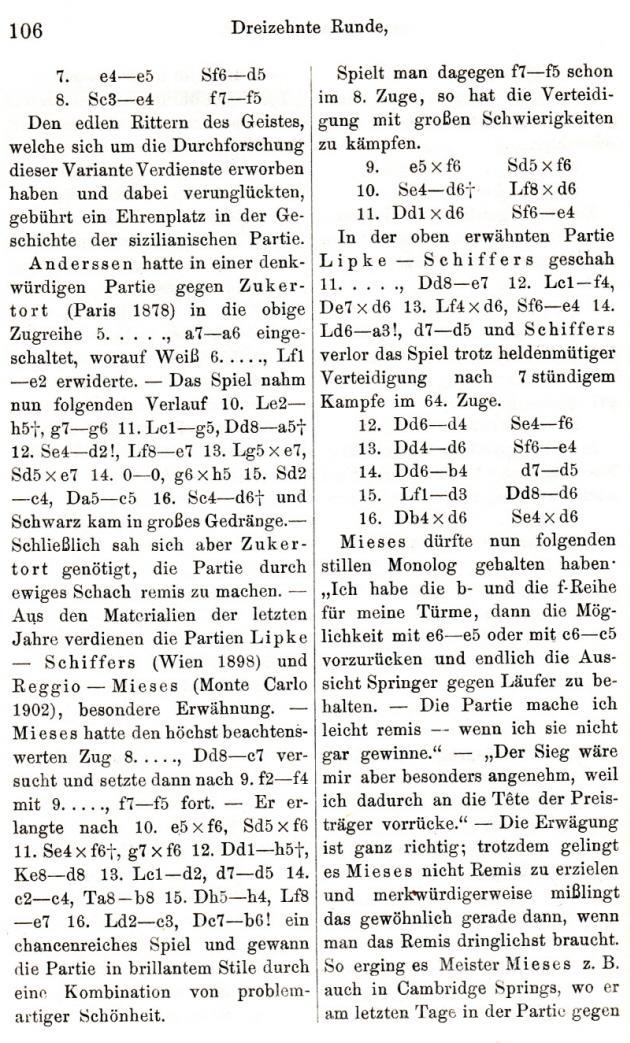

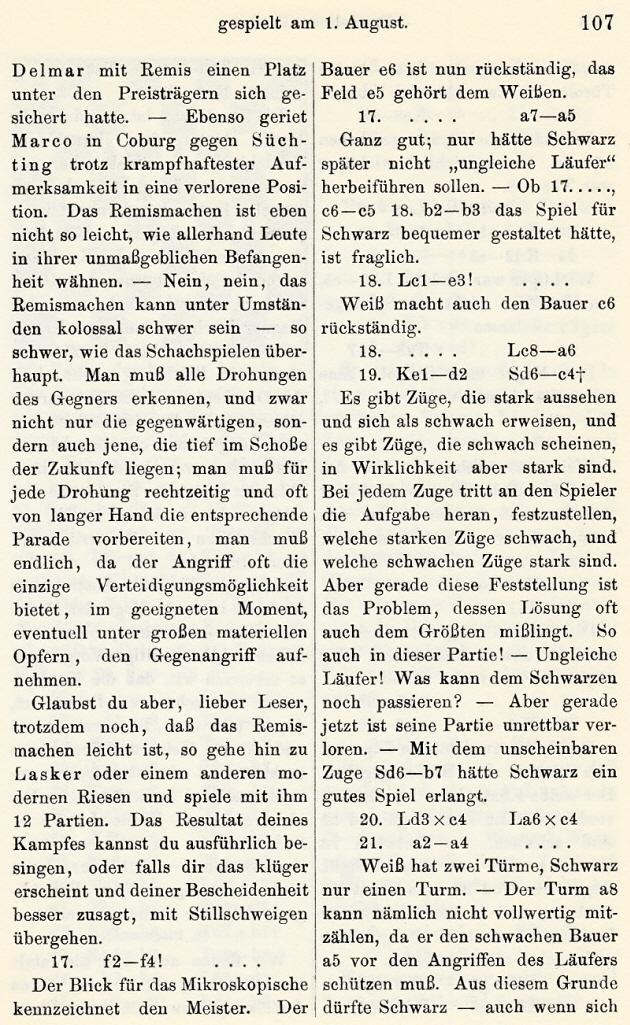

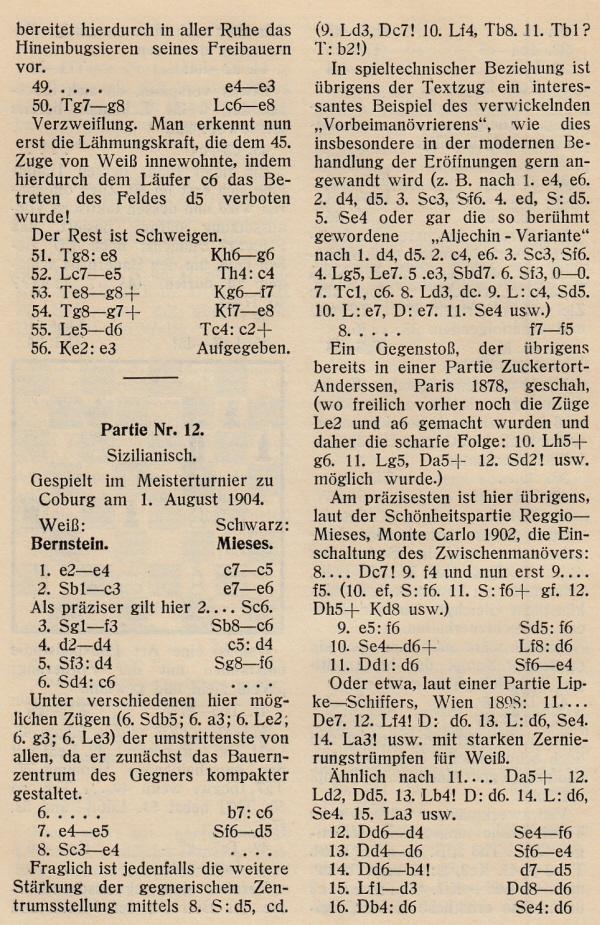

Below is the game as it appeared with Georg Marco’s annotations on pages 105-109 of the Coburg, 1904 tournament book, which Marco edited with Paul Schellenberg and Carl Schlechter. (The Vorwort on page iii specified that Marco annotated the Bernstein v Mieses game.)

The notes were reproduced on pages 361-364 of the December 1905 Wiener Schachzeitung.

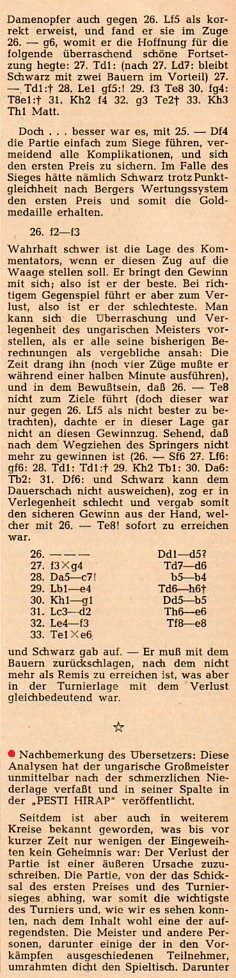

Next, Tartakower’s annotations from pages 36-39 of his monograph on Bernstein, Moderne Schachstrategie (Breslau, 1930):

The score according to the above German-language sources was: 1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 e6 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 Nf6 6 Nxc6 bxc6 7 e5 Nd5 8 Ne4 f5 9 exf6 Nxf6 10 Nd6+ Bxd6 11 Qxd6 Ne4 12 Qd4 Nf6 13 Qd6 Ne4 14 Qb4 d5 15 Bd3 Qd6 16 Qxd6 Nxd6 17 f4 a5 18 Be3 Ba6 19 Kd2 Nc4+ 20 Bxc4 Bxc4 21 a4 Kd7 22 b3 Ba6 23 Bb6 Bc8 24 Ke3 Ra6 25 Bc5 Kc7 26 Kd4 Bd7 27 Rae1 h5 28 Re5 g6 29 Rg5 Rg8 30 Ke5 Be8 31 Re1 Ra8 32 Kf6 Bd7 33 g3 Rae8 34 Ree5 Rh8 35 Rxg6 Rh7 36 Rg7 Reh8 37 Rxh7 Rxh7 38 Kg6 Rh8 39 Kg7 Rd8 40 Rxh5 Be8 41 Rh7 Rd7+ 42 Kh6 Rxh7+ 43 Kxh7 Bh5 44 h4 Bd1 45 c3 Bxb3 46 g4 Kd7 47 g5 e5 48 f5 Bxa4 49 f6 Resigns.

The position after 26...Bd7:

The Chernev books gave White’s 27th move as Rhe1 instead of Rae1.

A slightly different ending (without 46...Kd7) can also be found in some databases. Indeed, one database that we consulted offered three versions of the game, and none of them corresponded exactly to the moves in the tournament book.

As regards possible errors by Black, his 24th and 25th moves received question marks on page 45 of O.S. Bernstein (Grand maître international d’Echecs) by J. Cena:

On the same page Cena gave 27 Rae1, and not 27 Rhe1. The privately-printed book contains no date or place of publication; it was listed for sale on page 83 of the March 1968 BCM.

Moves 19-40 of the game (with 27 Rhe1) can be found on pages 43-44 of Positional Chess Handbook by Israel Gelfer (London, 1991). The only move criticized was 19...Nc4+, which Cena had passed over in silence.

In Logical Chess Move by Move (see, for instance, page 180 of the 1998 algebraic edition published by B.T. Batsford Ltd.), Chernev pointed out that at move 11/13 (taking account of a repetition of moves) Alekhine suggested ...Qb6. We are not aware that Alekhine ever annotated, or even mentioned, the Bernstein v Mieses game, but he commented on the position when it arose in Yates v Emanuel Lasker at New York, 1924. From page 186 of the tournament book:

Finally, concerning Bernstein’s 17 f4 Chernev wrote on page 161 of The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played:

‘It was about moves of this sort that the great annotator Marco said, “An eye for the microscopic betokens the master”.’

The quote was also included in Logical Chess Move by Move. From the above annotations in the Coburg, 1904 tournament book it will be seen that Marco’s comment in German was, on page 107:

‘Der Blick für das Mikroskopische kennzeichnet den Meister.’

(8704)

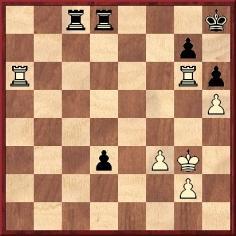

Black to move

The above position was given in William Winter’s Chess for Match Players, i.e. on pages 231-232 of the original 1936 edition and, as shown below, on page 232 of the revised 1951 work:

There is an obvious resemblance to the conclusion of Capablanca’s famous victory over Bernstein in Moscow, 1914 (given in My Chess Career), but what is the origin of this version?

(8747)

From page 75 of the 5/2014 New in Chess, in the lamentable ‘Fair & Square’ column:

What is known about this alleged remark of Capablanca’s, beyond its availability on a number of websites which document nothing?

(8768)

As noted in The Best Chess Games, on page 24 of Chess Masterpieces by F.J. Marshall (New York, 1928) Capablanca replied to a request to nominate his best game:

‘It is difficult to say; so much depends on the point of view. There are three possible types of best game – a fine attack, a brilliant defence, or a purely artistic treatment. ... I think my most finished and artistic game was the one I played against Dr Bernstein at Moscow on 4 February 1914.’

Among our critical comments about Treasure Chess by Bruce Pandolfini (New York, 2007) is the following:

Pandolfini even believes (pages 102-103) that Capablanca’s famous exhibition game in Moscow against Ossip Bernstein (29...Qb2) was played in the St Petersburg, 1914 tournament.

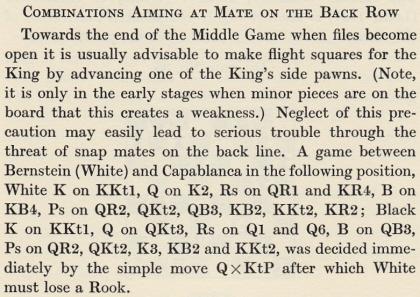

See also The Back-Rank Mate.

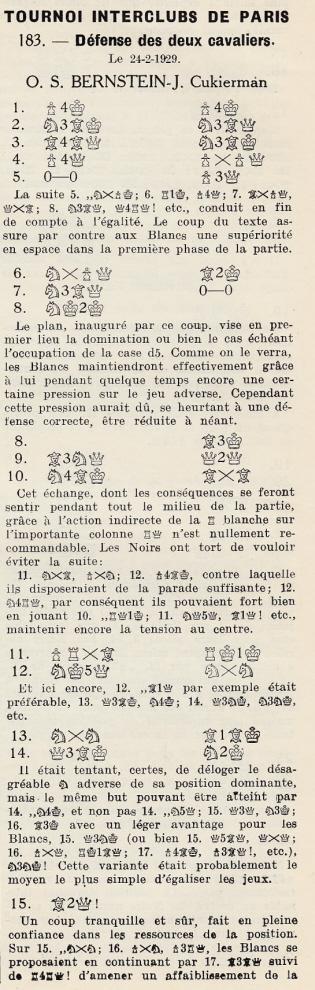

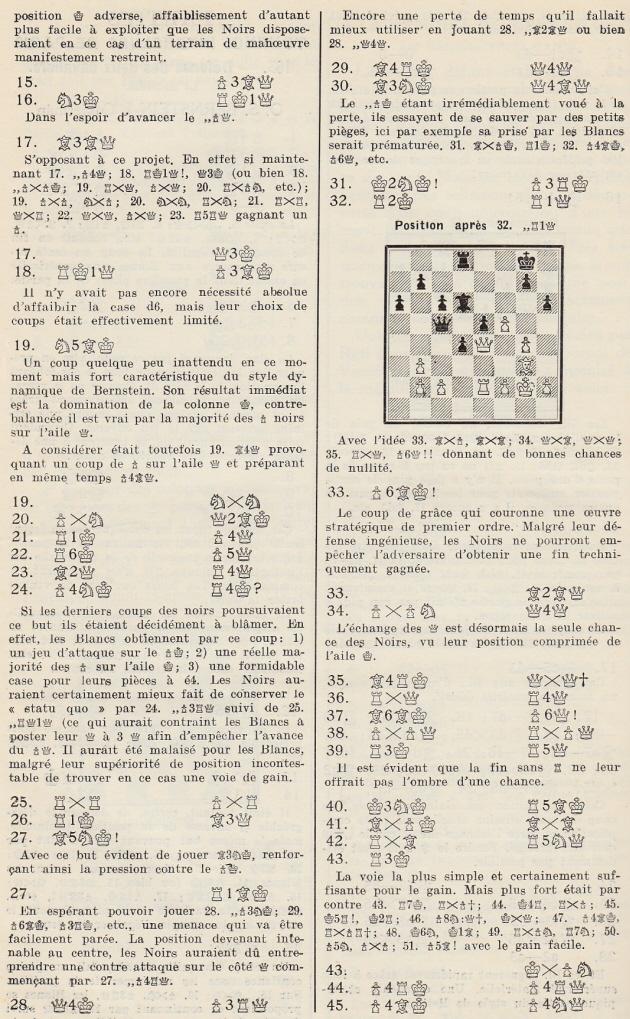

C.N. 3724 remarked that the Belgian magazine L’Echiquier sometimes employed an unusual form of the figurine notation. Below is the full game mentioned in that earlier item. It was given, with notes by Alekhine, on pages 339-341 of the August 1929 issue:

Ossip Samuel Bernstein – Josef

Isaevich

Cukierman

Two Knights’ Defence

Paris, 24 February 1929

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 d4 exd4 5 O-O d6 6 Nxd4 Be7 7 Nc3 O-O 8 Nde2 Be6 9 Bb3 Qd7 10 Nf4 Bxb3 11 axb3 Rfe8 12 Nfd5 Nxd5 13 Nxd5 Bf8 14 Qf3 Ne7 15 Bd2 c6 16 Ne3 Red8 17 Bc3 Qe6 18 Rfd1 f6 19 Nf5 Nxf5 20 exf5 Qf7 21 Re1 d5 22 Re6 d4 23 Bd2 Rd5 24 g4 Re5 25 Rxe5 fxe5 26 Re1 Bd6 27 Bg5 Rf8 28 Qe4 a6 29 Bh4 Qd5 30 Bg3 Qc5 31 Kg2 h6 32 Re2 Rd8 33 f6 Bc7 34 fxg7 Qd5 35 Bh4 Qxe4+ 36 Rxe4 Rd5 37 Bf6 d3 38 cxd3 Rxd3 39 Re3 Rd4 40 Kg3 Rf4 41 Bxe5 Bxe5 42 Rxe5 Rb4 43 Re3 Kxg7 44 h4 a5 45 f4 b5 46 h5 a4 47 bxa4 bxa4 48 Rc3 Rxb2 49 Rxc6 a3 50 Rg6+ Kh7 51 Ra6

51...Ra2 52 g5 hxg5 53 fxg5 Ra1 54 Ra7+ Kg8

55 g6 a2 56 Kg2 Rb1 57 Rxa2 Rb5 58 Ra8+ Kg7 59 Ra7+ Kg8 60 Rh7 Rg5+ 61 Kh3 Rg1 62 Kh4 Rg2 63 Ra7 Rg1 64 Ra4 Kg7 65 Rg4 Rh1+ 66 Kg5 Rh2 67 Rg1 Rh3 68 Ra1 Rg3+ 69 Kf4 Rg2 70 Ra5 Kh6 71 Rf5 Rg1 72 Ke5 Rg2 73 Rf8 Kg7 74 Rf7+ Kg8 75 Rb7 Re2+ 76 Kf6 Rf2+ 77 Kg5 Rf8 78 h6 Resigns.

(8766)

Alekhine’s reference at move 51 to Tarrasch and Chigorin concerns their ninth match-game. The remainder of C.N. 8766 gave a relevant extract from Der Schachwettkampf zwischen Dr. S. Tarrasch und M. Tschigorin, Ende 1893 by Albert Heyde (Berlin, 1893), pages 50-51.

See also our feature articles on Tarrasch and Chigorin.

C.N. 1041 from Was Alekhine a Nazi?:

It is sometimes implied, or even stated, that Alekhine did not deny authorship of the anti-Semitic articles until after the War was over. Note, however, this report in the January 1945 CHESS (page 53):

‘We knew that Dr Alekhine had made strenuous attempts to obtain a visa for the USA and, going entirely on our personal knowledge of him and a very few other facts, we announced it as our opinion that only the detention of his wife in France by the Nazis had prevented his leaving.

According to the report of an interview with Alekhine in Spain, published by the News Review, on 23 November, he claimed that the articles in question had been rewritten by the Nazis.’

A letter from Bernstein dated 5 October 1945 and published in the November 1945 CHESS (pages 28-29) has the following strong words about Alekhine:

‘My profound attachment to chess restrains me from telling all I think of Alekhine, since the fall of France. In May 1940, I played against him in Paris (a so-called “consultation” game) and won. I could not have guessed that he would behave afterwards as he did. I shall never play against him again and I do not even wish to see him. I refused to meet him at Barcelona, when he visited that city to give chess exhibitions.

I think that the above makes my conception of “collaboration” clear.

The chess world is aware of the tragic end of the grand Polish chessmaster and composer Dawid Przepiórka who was condemned to death for having entered a café where chess was played; he was forbidden to do that, because he was a Jew. But it is not generally known that Alekhine, though on close terms with the Nazi Governor of Poland, Dr Frank, with whom he was photographed for Nazi periodicals published at the time, refused to intervene to secure Przepiórka’s release. This fact of his non-intervention was told me by Sämisch when he came to Barcelona at the end of 1943. I could also mention articles published by Alekhine after 1940 and the chess exhibitions he gave to entertain the Nazi Forces. I refrain from giving further disgusting details about his behaviour. It could be added that he adopted the Nazi salute “Heil Hitler” with outstretched arm. I am fully aware of what my statements mean but I consider it my moral duty and I leave it to you to make conclusions.’

Alekhine replied in the January 1946 issue.

‘As for Dr Bernstein’s “information”, I can only state that my friend D. Przepiórka was murdered before the end of 1939 [sic] (I heard the narrative of his [sic] from an eye-witness) and it is known that I played in Germany and Poland only from the end of 1941. What connection could I have with this tragical event??

I may add that the game Dr Bernstein gives was played at my home and had an absolutely private character – but of course this has no importance at all.’

The Editor of CHESS added:

‘Dr Alekhine goes on to say that he has been very sick this year but had to go on playing, or starve. He has had a rest at Tenerife and is feeling much better, but ill-health and worry have sapped his playing ability.’

From the May 1946 CHESS, page 172:

‘In a letter to the editor, dated 10 April 1946, Madame Grace Alekhine emphatically refutes the charges against the world champion published in the Swiss news in April CHESS (page 147).

“My husband never accepted a salary nor the title of ‘Sachberater [sic] für Ostfragen’”, she says. “He was offered a very advantageous position provided he became a Nazi officially: this he refused to do. He had no influence with any of the ‘party leaders’, and never mixed politically. He was paid for each Tournament and Exhibition as usual; no more, no less.”’

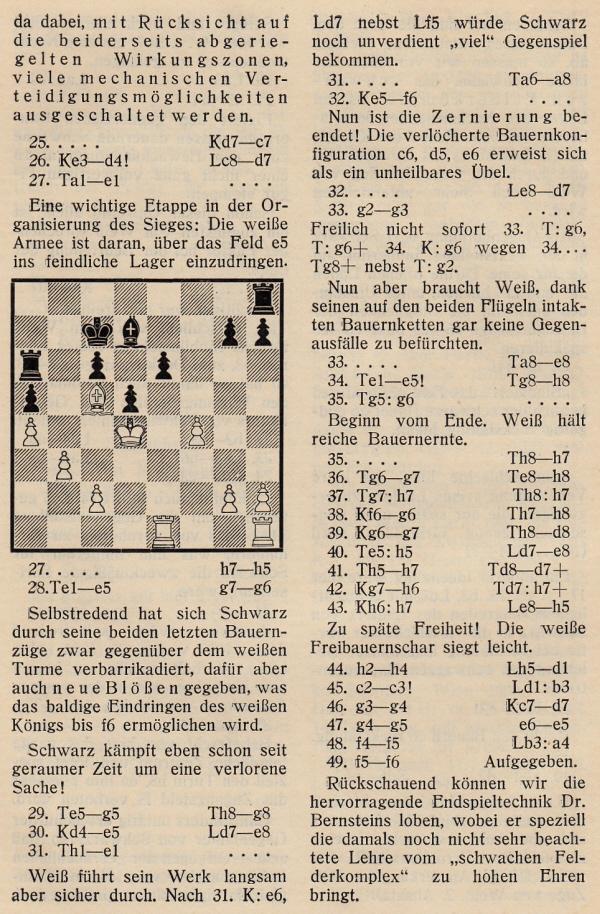

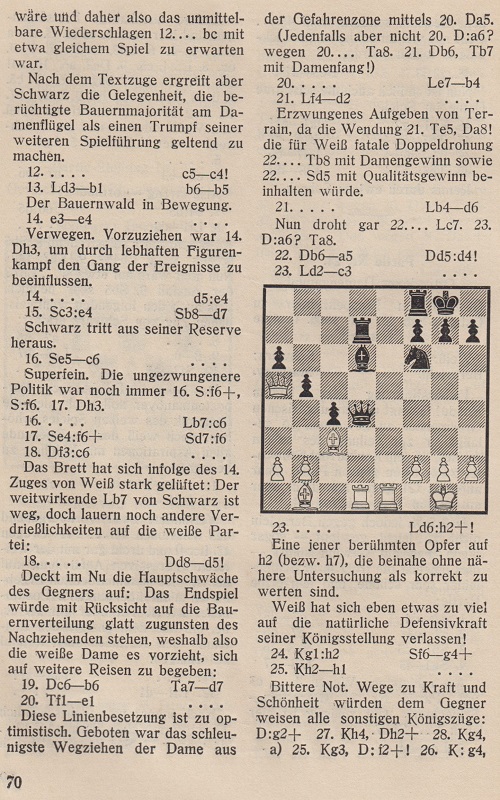

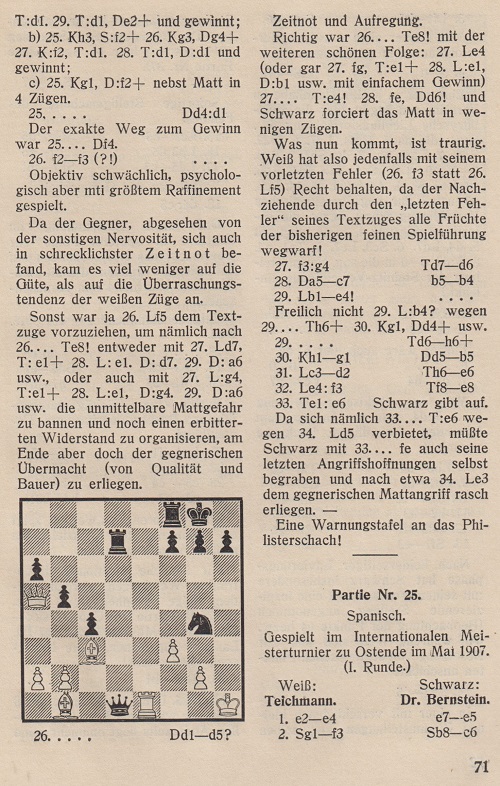

White to move

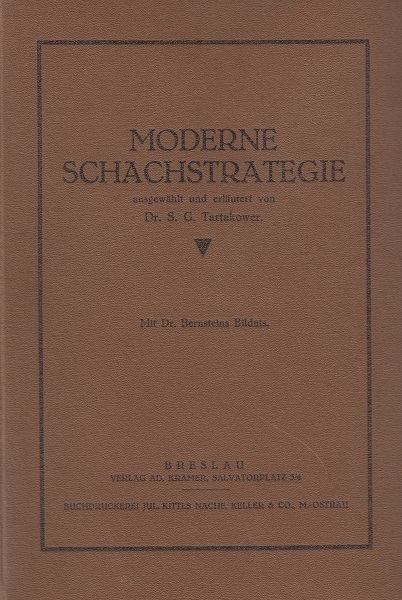

From page 10 of Chess Review, January 1952 in an article by Tartakower entitled ‘From My Chess Memoirs’:

The episode was also referred to by Albéric O’Kelly de Galway on page 266 of the September 1956 Chess Review:

‘Bernstein narrates the following concerning his game against Maróczy. In a desperate position and about to resign, he saw that his opponent had only 30 seconds for three moves to the time-limit, while he himself had half an hour. Knowing a normal move must lose quickly, he suddenly made a move which was rather stupid. As he expected, his opponent was caught by surprise, flushed nervously, overlooked the winning move and lost.’

The Bernstein v Maróczy game: 1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Nf3 Be7 5 Bf4 O-O 6 e3 b6 7 cxd5 exd5 8 Bd3 a6 9 O-O Bb7 10 Ne5 c5 11 Qf3 Ra7 12 Rad1 c4 13 Bb1 b5 14 e4 dxe4 15 Nxe4 Nbd7 16 Nc6 Bxc6 17 Nxf6+ Nxf6 18 Qxc6 Qd5 19 Qb6 Rd7 20 Rfe1 Bb4 21 Bd2 Bd6 22 Qa5 Qxd4 23 Bc3 Bxh2+ 24 Kxh2 Ng4+ 25 Kh1 Qxd1

26 f3 Qd5 27 fxg4 Rd6 28 Qc7 b4 29 Be4 Rh6+ 30 Kg1 Qb5 31 Bd2 Re6 32 Bf3 Rfe8 33 Rxe6 Resigns.

The game was annotated on pages 69-71 of Moderne Schachstrategie (Breslau, 1930), a monograph on Bernstein by Tartakower.

Other notes can be found on pages 395-400 of the Caissa Editions book on Ostend, 1906 edited by A.J. Gillam (Yorklyn, 2005), and a computer-check of the game will be found particularly valuable. A curiosity is that on page 177 of the June 1952 BCM E.G.R. Cordingley stated that the game was drawn.

(10300)

Position after 26 f3

From Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany):

‘According to W.A. Földeák in the 18/1967 issue of Schach-Echo, pages 285-286, Maróczy refrained from playing 26...Re8 because H. Wolf, who was standing in the crowd of onlookers, had audibly but inadvertently mentioned the possibility of that winning move.’

On pages 284-286 Schach-Echo gave the full game with Maróczy’s annotations translated from Hungarian into German. Below is the conclusion and Földeák’s afterword.

(10326)

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) draws attention to an interview with Ossip Bernstein on pages 4-5 of the Neues Wiener Journal, 3 November 1925.

(10760)

On page 16 of the January 1956 Chess Review Ossip Bernstein described the oscillating relationship between Janowsky and Léonardus Nardus and concluded:

‘A few weeks before Janowsky’s death in 1927 he fell very ill. I cabled Nardus, who then lived in Tunisia, and he immediately sent a substantial amount of money for Janowsky.’

(10869)

On the subject of draws, C.N. 2549 (see page 359 of A Chess Omnibus) quoted this remark on Rubinstein by L. Steiner on page 54 of the March 1961 Chess World:

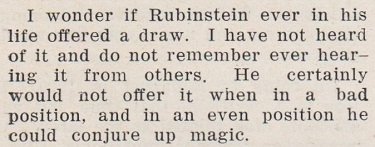

A claim about Emanuel Lasker’s practice appeared in ‘My Encounters with Lasker’ by Ossip Bernstein on pages 202-204 of the July 1955 Chess Review:

(11400)

From Where Did They Live?, below are three addresses of Ossip Bernstein:

rue Emile Augier 9, Paris, France (Ranneforths Schach-Kalender, 1922, page 94);

Bayrischer Platz 4, Berlin W 30, Germany (Ranneforths Schachkalender, 1925, page 135);

10 rue des Marroniers, Paris XVI, France (Wiener Schachzeitung, September 1929, page 268) and Ranneforths Schach-Kalender, 1930, page 63).

The Gallica website has two fine photographs of Ossip Bernstein dated 1927.

(11657)

Courtesy of Sergey Voronkov and Vladislav Novikov (Moscow), below is part of page 130 of the Russian magazine Shakhmatnoe Obozrenie (April 1903 issue):

The diagram on the left is the oldest composition by Ossip Bernstein in the van der Heijden database.

(11938)

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.