Edward Winter

A number of Chess Notes items have discussed the old masters’ nominations for their best games, and we summarize here the various choices made.

On page 221 of the first volume of his Best Games collection, published in 1953, Tartakower wrote:

‘An investigation carried out some years ago by the eminent editors of the Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français (MM Gaston Legrain and then François Le Lionnais) dealt with the presentation to the public, in so far as the leading contemporary players were concerned, of the games they were most proud of.

As for me, it is usually my victory with White against Schlechter at St Petersburg, 1909, or else that with Black against Maróczy at Teplitz-Schönau, 1922, that writers think fit to commend most to the attention of their readers.

Nevertheless, I derive most pleasure from the present short but expressive game’ (Tartakower v Przepiórka, Budapest, 1929).’

On a number of other occasions Tartakower picked out his best/favourite, etc. game:

In Marshall’s Chess Masterpieces (pages 41-47) he stated that his win over Maróczy at Teplitz-Schönau, 1922 was his best game. (His exact words are quoted later in the present article.);

On pages 241-244 of CHESS, 14 March 1939 he gave his draw against Capablanca at London, 1922, calling it ‘the most terribly pulse-stirring flight [sic] of my whole chess career’;

In Chess Review, June 1951 (pages 170-171) he wrote that his favourite game was his win over Vidmar at Vienna, 1905. (The score was given on pages 4-6 of his first Best Games book.)

Here are some other masters’ selections, taken from the 1930s series in Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français referred to by Tartakower:

E. Znosko-Borovsky: Capablanca v Znosko-Borovsky, St Petersburg, 1913 (volume 2, pages 189-190);

R. Spielmann: Spielmann v Rubinstein, Carlsbad, 1911 (volume 3, pages 324-325);

For Marshall’s book Chess Masterpieces (New York, 1928), the world’s leading masters (and a few others) nominated their best game:

R. Spielmann: Spielmann v Vidmar, Semmering, 1926 (page 1);

A. Nimzowitsch: ‘The one I played in the Dresden Tournament in 1926 against Rubinstein, who is, as you know, an extremely dangerous antagonist. I do not know any other of my important games which so well illustrates the principle of effective hindrance of the adversary’s forces, while at the same time securing the mobility of one’s own forces.’ (page 6);

M. Vidmar: Vidmar v Nimzowitsch, New York, 1927 (page 12);

F.J. Marshall: ‘I think that my best game was the one against Bogoljubow in the 1924 New York International Tournament. It is rarely that a mate in five moves is announced against a grand master in an important tournament.’ (page 18);

J.R. Capablanca: ‘It is difficult to say; so much depends on the point of view. There are three possible types of best game – a fine attack, a brilliant defence, or a purely artistic treatment. ... I think my most finished and artistic game was the one I played against Dr Bernstein at Moscow on 4 February 1914.’ (page 24);

G. Maróczy: Maróczy v Chigorin, Vienna, 1903 (page 30);

A. Alekhine: Réti v Alekhine, Baden-Baden, 1925 (page 35). (When annotating it in his second Best Games collection (published in 1939) Alekhine wrote: ‘I consider this and the game against Bogoljubow at Hastings, 1922 the most brilliant tournament games of my chess career.’);

S. Tartakower: ‘I consider [Maróczy v Tartakower, Teplitz-Schönau, 1922] to be my best game, because it was played against a master of the highest rank, and victory was not obtained through a serious blunder by my opponent, and because the sacrifice which I made at the 17th move, when subsequently analysed in all the variations, was proved to be perfectly sound.’ (page 41);

Edward Lasker: Torre v Ed. Lasker, Chicago, 1926 (page 48);

F.D. Yates: ‘I have selected [Yates v Takács, Kecskemét, 1927] because it is one true to type – that is to say, typical of my own style of play ... Of my own games I like this one best, as it has sound sacrificial combinations and was played in an important match.’ (page 55);

Emanuel Lasker: ‘I think the game I won against Pillsbury in the St Petersburg Tourney in 1896 to be the best I ever played. I was just able to ward off a furious attack and then succeed in carrying my own counter-attack through. It is true that I missed the logical continuation at one point, owing to fatigue and time pressure, and so had to win the game twice; but then the sacrificial termination has some merit.’ (page 60);

J. Barry: Barry v Pillsbury, Boston, 1899 (page 67);

W. Winter: ‘I consider [Winter v Vidmar, London, 1927] to be my best game partly on account of the eminence of my opponent and partly because of the importance of the occasion on which it was played, and also because on three occasions in which the situation was extremely complicated, I was fortunate enough to discover the only continuation which not only was necessary to secure victory, but to actually save the game.’ (page 72);

M. Euwe: ‘I consider [Euwe v Alekhine, 8th match-game, 1926-27] to be my best game principally because I like it best myself. From your point of view it may not fulfill all requirements, there being no sacrifices or brilliancies, but, when it is considered that it was played against the player who shortly afterwards became the world’s champion, and that I had the temerity to go in for what might be termed an audaciously novel opening, I think you will agree with me that I have a certain justification for making this selection.’ (page 78);

E. Colle: ‘I have not played such a lot of fine games as to make the selection really difficult, but still it is not easy to define accurately what is really one’s best game. One of the reasons – not a very good one, but still a reason – for selecting [Colle v Grünfeld, Berlin, 1926] is that it was awarded the first brilliancy prize.’ (page 83);

Sir George Thomas: ‘I find it uncommonly difficult to pick on a game to send you. To be honest – I have never played a game that completely satisfied me. However, I enclose a game [Alexander v Thomas, London, 1919] which has the merit of a rather entertaining combination, which was subsequently proved to be thoroughly sound. The play on both sides in the earlier stages of the game probably leaves much to be desired, but the long period in which the rook remains en prise is rather amusing.’ (page 88); [See too C.N. 2130 in Sir George Thomas.]

A. Rubinstein: Rubinstein v Lasker, St Petersburg, 1909 (page 94);

C. Howell: ‘I have hesitated to send you this game [Howell v Ford, New York, 1904] as the casual chessist may find it dull and it is not a masterpiece. Strictly speaking I don’t think I have ever perpetrated a masterpiece. As you know I have always played to win, and the few brilliancies I have had were due to the feeble play on the part of my opponents, and therefore gave me no satisfaction. The game I now send I like because it has some lessons for an earnest student.’ (page 101);

A.B. Hodges: ‘As my chess career began nearly 50 years ago, I find it somewhat difficult to decide on my best game. To be worthy of inclusion in the series you are compiling, I think that there are certain essentials to be considered. The opponent must have been a prominent figure in the chess world, and there must be no flagrant error in his play. With these factors in mind, I think that my game with Dr Emanuel Lasker was my best effort. It was played in New York in 1892 ...’ (pages 107-108);

W. Napier: ‘I consider the best game I ever played was against Dr Lasker at Cambridge Springs in 1904. I was particularly anxious to win this game, as I knew it would help you (not that you required any help) to clinch first prize. At one period of the game, the Doctor had to make nine moves in three minutes, and I felt that my game was safe. He made these moves however with such diabolical cunning and precision that I lost the game. I don’t suppose however this is what you want, so I send you my game with Chigorin in the Monte Carlo Tournament of 1902. It may be some justification for my selecting this game that it was awarded the Rothschild Brilliancy Prize.’ (pages 115-116);

J. Sawyer: the drawn game Marshall v Sawyer, Montreal, 1928. (page 120);

Few writers have presumed to nominate the best chess game ever played by anyone, though Irving Chernev’s choice of Bogoljubow v Alekhine, Hastings, 1922 is familiar. (See pages 281-283 of his 1968 book The Chess Companion.) Another instance is to be found on page 3 of G.A. MacDonnell’s Chess Life-Pictures (London, 1883). ‘No grander battle has ever, in my opinion, been recorded in chess annals’ was the exuberant MacDonnell’s description of the well-known consultation game between Anderssen, Horwitz and Kling (White) and Staunton, Boden and Kipping (Manchester, 6-7 August 1857).

In the Pittsburgh Dispatch of 18 November 1902, Napier wrote of Steinitz v von Bardeleben, Hastings, 1895 that there was ‘no finer game extant’. Source: Napier The Forgotten Chessmaster by John S. Hilbert (Yorklyn, 1997), page 62.

The Strand Magazine seldom had articles on chess, but one such was published on pages 722-725 of the December 1906 issue, headed ‘The Best Games Ever Played at Chess by J.H. Blackburne, British Chess Champion [sic]’. He wrote:

‘I will now proceed to consider three games which stand on record as perhaps the most brilliant in the annals of chess.’

The three were Anderssen’s Immortal Game (‘This is considered by many to be the most beautiful ending ever played’), Zukertort v Blackburne at London, 1883 and Morphy’s ‘brilliant little gem’ against the Duke and Count at the Paris Opera, 1858. [See C.N. 3851 below.]

The Morphy game is a popular choice. In C.N. 2287 Yasser Seirawan wrote to us:

‘Regarding the best game of chess ever played, certainly none of my own games spring to mind. Morphy v the Duke and Count is arguably the most quoted game of all time and has much that is special about it. It is fair to say that no other game has brought so much pleasure to so many. The best game of chess ever played? Can there be such a thing? Would a perfect game not be boring? Can a mere off-hand game be the best ever? I don’t know the answers, and in spite of the questions, Morphy v the Duke and Count gets my vote.’

Subsequently (see page 148 of A Chess Omnibus) we quoted a contrasting view, from pages 4-5 of Learn Chess by John Nunn (London, 2000):

‘It’s not an especially good game, as one might expect when the strongest player of his day confronts two duffers.’

On such matters, of course, there can be no consensus, or any reason for one. Even terms like ‘best’, ‘greatest’ and ‘most beautiful’ could be debated ad infinitum. And then there is the adjective ‘perfect’. On pages 334-335 of the October 1919 BCM B. Goulding Brown described the game H.E. Atkins v J. Barry (in the 1910 Anglo-American cable match) as ‘the nearest that I know to perfection’, and The Golden Treasury of Chess by Francis J. Wellmuth (New York, 1943) gave it on pages 172-173 with the heading ‘The Perfect Game’. Atkins’ victory was also highly praised by Emanuel Lasker in his annotations in the New York Evening Post, which were reproduced on pages 75-76 of the American Chess Bulletin, April 1910. The world champion concluded:

‘Mr Atkins must be congratulated upon this game, in which every move he made, starting with his eighth, is beyond criticism.’

That assessment was quoted by Fred Reinfeld when he gave the game on pages 70-72 of A Treasury of British Chess Masterpieces (London, 1950). Lasker had preferred 7 Qd2, on the grounds that 7 Nb5 ‘puts the white knight out of play’, but Reinfeld regarded this as ‘carping criticism’ and concluded:

‘Had Lasker omitted the qualifying phrase, he would have been more just as well as more generous.’

Other documented nominations of the kind discussed above continue to be sought.

The above article appeared at Chessbase.com on 21 June 2008. A follow-up article dated 27 June 2008 gave complementary information and game-scores.

See too pages 391-394 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves. and, regarding Atkins v Barry, C.N. 2229 in Chess Jottings.

As noted in C.N. 434 (reproduced on pages 234-235 of Chess Explorations) C.J.S. Purdy described the 11th match-game in the 1927 match between Capablanca and Alekhine as ‘possibly the greatest game of chess ever played’.

The Strand Magazine, the monthly periodical of the chess patron Sir George Newnes, Bart. seldom had articles on chess, but one such was published on pages 722-725 of the December 1906 issue:

‘The Best Games Ever Played at Chess by J.H. Blackburne, British Chess Champion [sic]

Brilliancy in chess is a rarity. It is like the sparkling of a multi-faceted diamond, which can illume darkness and shine best under provocation. Electricians would say it is the bright spark that signalizes the overcoming of resistance. It is not a very common or ordinary experience. It would cease to be a wonder if it were. It would fail to command the great admiration usually bestowed on things of rarity.

The best quality of brilliancy occurs between great contending forces – the powers of antagonistic minds. And so it is that, generally speaking, the highest products issue from conflict wherein very great players are engaged – players accustomed to exert very strong powers of mind against their adversaries. There is then the pressure of strong and skilful opposition provoking strong display, until at length out flashes the brilliancy which thrills the spectators as well as the producer, and sometimes has almost a benumbing effect upon the vanquished player.

Brilliancy in actual play very often prevails in spite of a flaw – the dazzling effect, as it were, rendering the flaw invisible.

Sound or flawless brilliancy in chess is the brilliancy that deserves the fullest consideration. The production of it sheds lustre on the happy producer, while it also serves a high educational function in giving us something to admire and study.

The alternation of stroke or “move”, combined with the necessity of parrying as well as delivering the stroke, has brought about in chess a practice of adopting aggresso-defensive tactics. It has developed an even higher ideal. It has led to the adoption, wherever possible, of a doubly attacking move – such as that of a knight forking two of the adverse pieces, or that of a bishop attacking or pinning on the one diagonal two or more of the opposing pieces. And, better still, it has led to the adoption, wherever possible, of such forking or raking moves as will include a check, or double check, to the adverse king; and, higher still, a move which, under every conceivable circumstance, will enable the player next moving to adopt one of these many-purpose moves.

It is chiefly in pursuit of some of these advantageous moves that brilliancy occurs. It may occur as a means of withdrawing, or paralyzing, or obstructing some of the hostile pieces, so as to get them out of the way or nullify their action, or make them embarrass their own king’s mobility. Design is the prolific source of ingenious brilliancy; yet, in a minor degree, luck contributes to the production. Some of these observations can be tested in examining the sample games appended.

Meanwhile a few words as to famous exponents of brilliancy in the past.

First and foremost comes the immortal Morphy, who in 1858 came over from America and overwhelmed all the European masters, or, at least, those who cared to oppose him. His games were splendid specimens of brilliancy; and probably many of his sparkling gems will be reproduced, studied, and admired when the efforts of the so-called “position player” and the “accumulator of minute advantages” school have been forgotten. Then there was Labourdonnais, the renowned French expert, who also vanquished all-comers; and what chessplayer has not received pleasure and instruction in playing over the games of Professor Anderssen and his illustrious pupil, Dr Zukertort?

Then, again, there was Captain Mackenzie, a Scot by birth, an enthusiastic disciple of Morphy, and who became champion of America after that master’s retirement.

De Vere, at one time British chess champion; the two Macdonnells, both Irishmen; Pillsbury, and Baron Kolisch were all worthy exemplars of brilliancy.

And last, though not least, the young Hungarian, Charousek, who a few years ago startled the chess world by his aggressive and hazardous play against older and more experienced masters, and justly earned the title of the “New Morphy”; and, considering his short chess career, has left us wondering what he might not have attained had he lived.

To living masters like Bird, Maróczy, Marshall, Janowsky and Chigorin, it is hard to do justice without seeming to indulge in flattery; yet it is not possible to omit them and give anything like a true account of chess brilliancy. We have in England for nearly two-thirds of a century enjoyed the splendid style of Mr H.E. Bird, especially notable for his originality. He may by his devotion to brilliancy have several times missed the chess crown. He has always apparently set less value on that than on the achievement of some brilliant mate. The same may be said of Chigorin, the famous Russian player. Marshall and Janowsky have given us many pieces of rich brilliancy, and Maróczy for his time has pretty well earned a title to brilliancy. But for him the future has still much in store.

Brilliancy does not appear to be on the wane. The new school (as a fresher one than the “modern”) is distinctly endued with love of adventure and brilliancy. The younger players, under its healthy influence, are able, when taking part in tournament play, to infuse life and brilliancy into their games and suffer nothing as a penalty for rashness. It is a good sign, and possibly portends further improvement in this direction.

I will now proceed to consider three games which stand on record as perhaps the most brilliant in the annals of chess.’

The three were Anderssen’s Immortal Game (‘This is considered by many to be the most beautiful ending ever played’), Zukertort v Blackburne at London, 1883 and Morphy’s ‘brilliant little gem’ against the Duke and Count at the Paris Opera.

(3851)

Peter Morris (Kallista, Victoria, Australia) notes that ‘favourite games’ were presented on pages 226-281 of Chess Treasury of the Air by Terence Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966):

(5650)

Some observations by Wolfgang Heidenfeld on page 9 of the January 1966 BCM (in D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column):

‘In connection with the various “best game” lists and their coupling with specific masters, it has occurred to me that there is a slight ambiguity in the meaning of the term “best game”. Take Fischer as an example. The game which Fischer played best may be the magnificent brilliancy against Donald Byrne, which he won at the age of 13; or it may be his win against Gligorić at the Candidates’ tournament, 1959; or again it may be the much-advertised “game of the century” [sic] against Robert Byrne. Yet I would call none of these “Fischer’s best game”, because the opposition did not play well enough. Fischer’s best game – that is the best game in which Fischer was involved – was undoubtedly his first-round draw against Gligorić at the Bled tournament, 1961.’

The draw is game 30 in Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games. Heidenfeld annotated it on pages 145-146 of his posthumous book Draw! (London, 1982).

(6022)

On page 232 of the August 1970 BCM Wolfgang Heidenfeld wrote:

‘... a phrase like “Alekhine’s Best Games” is really ambiguous: it may mean two entirely different things, viz. (a) the games Alekhine played best and (b) the objectively best games in which Alekhine was a participant (in which the standard of the game is achieved by both partners) – thus he need not necessarily have won them. This, in fact, is the basis of my anthology Grosse Remispartien.

In fact, it is little short of ludicrous that Alekhine’s Best Games does not contain his draw against Marshall at New York, 1924, where a most original and new strategic conception by Marshall is met by an amazing tactical finesse of Alekhine’s, the whole (drawn) game being one of the greatest ever played. It is similarly ludicrous that Golombek’s anthology of Réti’s Best Games is without his draw against Alekhine at Vienna, 1922 – which has been christened the Immortal Draw and which even Alekhine does not pass over in his own collection. Similarly some game collections of Tal’s are deprived of the fantastic draw against Aronin at the 24th Soviet championship (Moscow, 1957) – a game of which Keres stated in a much-acclaimed article that one could not do justice to Tal’s achievement in that tournament without coming to grips with it.’

(7049)

In an article on pages 406-408 of the September 1976 BCM D.J. Morgan related that in 1938 (late June) he learned from James Gilchrist of Jacques Mieses’ arrival in England (‘he has made a hurried escape from Nazi Germany’). Morgan resumed his old acquaintance with Mieses the next day and noted that ‘in his flight he had brought little with him except his wonderful chess endowments’. Morgan added:

‘The afternoon and evening glowed with chess memories and demonstrations. In particular, he spoke with endearing words of the great Carl Schlechter, and played from memory the game which he won as Black from Carl at St Petersburg, 1909, a feature of which was the unusual activity of Black’s queen. But his favourite among his own games was the one he won from Janowsky at Paris, 1900.’

On pages 86-87 of the May-June 1935 issue of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français Mieses annotated the Janowsky game. He stated that selecting it as his favourite game had not been easy, since over a dozen of his games had won prizes and his preferences sometimes changed: ‘ayant joué dans ma carrière plus d’une douzaine de parties récompensées par un prix de beauté, je me trouve dans la situation d’un père qui a plusieurs enfants chéris et dont la prédilection pour l’un ou l’autre change de temps en temps.’

‘My Most Exciting Game’ was the title of an article by Mieses on pages 280-281 of CHESS, 14 April 1939. He selected his win over Curt von Bardeleben at Barmen, 1905 – ‘it holds as much interest and excitement as I would ever wish to experience’. Mieses added that ‘Curt von Bardeleben at his best was one of the strongest players of all time’.

(6430)

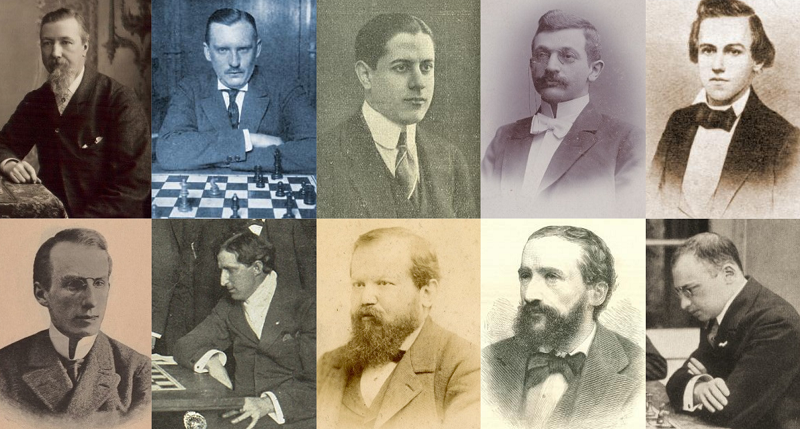

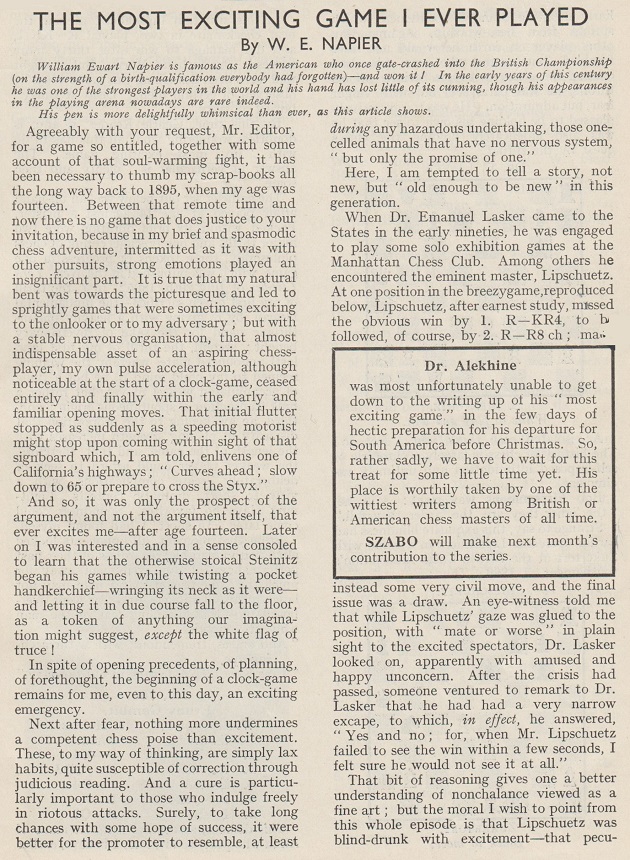

From pages 179-181 of CHESS, February 1939:

In the first diagram a black pawn is missing from c5. The remark by Napier in the ensuing paragraph is notable:

‘The history of chess is largely a chronicle of self-imposed intimidation and untimely excitement.’

It is also worth highlighting the CHESS Editor’s comment about Napier in the box on page 179: ‘one of the wittiest writers among British or American chess masters of all time.’

Napier’s article and the game against Helms were discussed on pages 13 and 339-341 of Napier The Forgotten Chessmaster by John S. Hilbert (Yorklyn, 1997). Helms wrote tributes to Napier on pages 86-87 of the September-October 1952 American Chess Bulletin and on page 70 of CHESS, Christmas 1952/January 1953.

(10690)

See pages 83-84 of Chess Explorations and The Australian Nimzowitsch for the correspondence game Purdy v Crowl about which the former wrote (CHESS, 14 November 1938, page 89):

‘... easily the most exciting game I ever played, or am ever likely to play ... Both the winner and the loser declared, and still declare, this game to be the best in which either has ever taken part – surely a record’.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.