Edward Winter

The biography of a British Prime Minister is an unlikely place to find the moves of a chess game, but one is given on page 541 of Robert Blake’s book on Andrew Bonar Law (1858-1923), The Unknown Prime Minister (London, 1955). It was culled from page 122 of Chernev’s 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955). Black was Brian Harley, who had given the score on pages 62-63 of Chess and its Stars (Leeds, 1936), a book with a chapter on Bonar Law which included a game won by Capablanca against Bonar Law and two other Members of Parliament. Harley described Bonar Law as ‘a strong player, touching first-class amateur level, which he had attained by practice at the Glasgow Club in earlier days’. Harley wrote that he played over a thousand games against Bonar Law in the period after the Great War, and that the future Prime Minister had remarked to him that chess was ‘the only thing that keeps my mind on itself’.

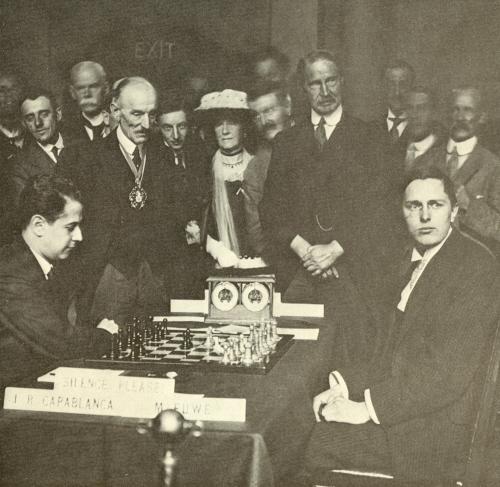

The above photograph, taken at the start of London, 1922 and with Bonar Law standing on the right, has been published quite extensively, e.g. on page 83 of A Book of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1973). A second shot from the same occasion appeared opposite page 216 of Glorias del Tablero “Capablanca” by José A. Gelabert (Havana, 1923):

Another chess figure to face Bonar Law over the board was Jacques Mieses, who wrote a brief article ‘Reminiscences of Bonar Law as a chessplayer’ on pages 211-212 of the August 1941 BCM. He recalled that in Glasgow in January 1900 ‘for several weeks Bonar Law was my daily opponent on the chess board’ and that they played about 30 games:

‘His practical playing strength and his comprehension of the deeper points of the game actually extended far beyond mere dilettantism. He took every game rather seriously, but without abusing the opponent’s time and patience by playing too slowly. Regarding his style of play, I found him less inclined to the attack than to the defence, which he usually conducted skilfully and with great prudence. Being deliberate and cautious in his decisions, he refrained on principle from any rash or very risky-looking enterprise. What struck me as a remarkable quality in Bonar Law as a chessplayer was his undauntedness even against the strongest opposition. …When I offered him a sacrifice, the last consequences of which he was not able to see through, but the perfect soundness of which he doubted, he never hesitated to accept it. He was a fearless player, relying on his own well-balanced judgment of position with a significant self-confidence quite free from conceit. Anyhow, it might be considered as a noteworthy fact, interesting not only to the chess world, but also to the psychologist, that Bonar Law as a chessplayer demonstrated all the typical features of character he afterwards so successfully proved in his splendid career as a politician.’

Page 474 of the December 1911 BCM stated that Bonar Law was believed to have been a member of Glasgow Chess Club since 1886 and that, ‘with the possible exception of Mr W.W. Rutherford, of Liverpool, Mr A. Bonar Law is probably the strongest chess-playing member of the present House of Commons’. Eight years later the magazine had not changed its mind. Page 10 of the January 1920 issue again named the two as the strongest Members of Parliament. This was on the occasion of Capablanca’s 40-board simultaneous display at the House of Commons, during which Rutherford was one of only two players to draw.

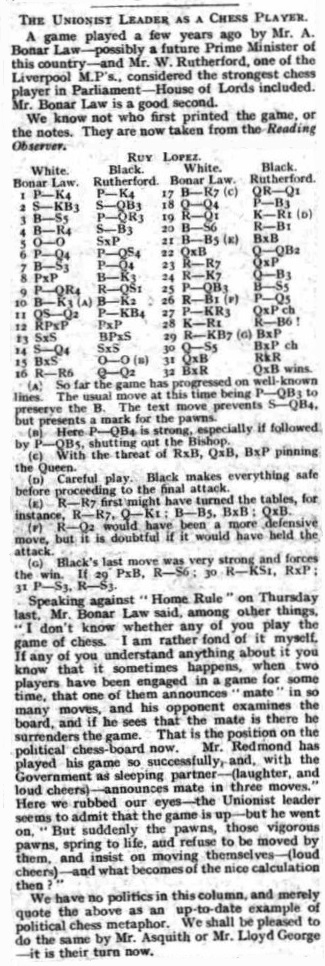

The following game shows the two politicians in play:

Andrew Bonar Law – William Watson Rutherford

(Venue?) 1913 [See, however, the addition of 10 March 2024

below.]

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Nxe4 6 d4 b5 7 Bb3 d5 8 dxe5 Be6 9 a4 Rb8 10 Be3 Be7 11 Nbd2 f5 12 axb5 axb5 13 Nxe4 fxe4 14 Nd4 Nxd4 15 Bxd4 O-O 16 Ra6 Qd7 17 Ba7 Rbd8 18 Qd4 c6 19 Rd1 Kh8 20 Bb6 Rc8 21 Bc5 Bxc5 22 Qxc5 Qc7 23 Ra7 Qxe5 24 Re7 Qf6 25 c3 Bg4 26 Ra1 d4 27 h3 Qxf2+ 28 White resigns.

Source: American Chess Bulletin, January 1914, page 10. The Bulletin took the game from the Weekly Irish Times.

Page 281 of the September 1917 BCM reported that Bonar Law had accepted a vice-presidency of the Imperial Chess Club. ‘Formerly he was an amateur of more than average skill, and he still plays an occasional game in the House of Commons smoking-room, but the time when he was able to keep up regular practice must seem remote.’

The January 1919 BCM (pages 12-13) referred, with some scepticism, to a newspaper report that at Bootle on 3 December 1918, during the General Election campaign, Bonar Law had declared, ‘One of the results of the War must be to make it plain that men who deliberately, as in a game of chess, plunged the world into a conflict for the sake of gain to themselves should always be held guilty of bloodshed.’

(Kingpin, 1998)

Addition on 10 March 2024:

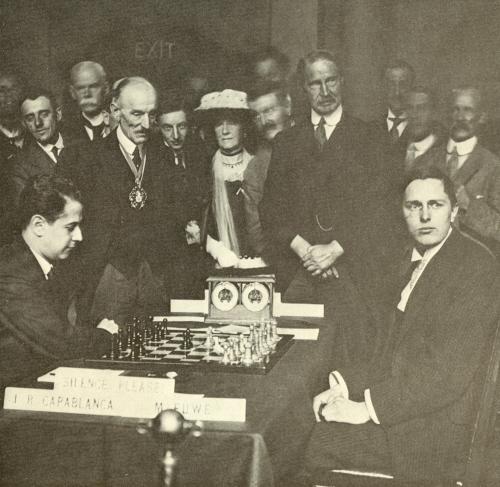

John Saunders (Kingston-upon-Thames, England) adds that the above game against Rutherford was published on page 6 of the Cheltenham Examiner, 14 December 1911:

Our correspondent notes that a few extra moves are given and that, already in 1911, the game was said to have been played ‘a few years ago’. Can its appearance in the Reading Observer or any earlier publication be traced?

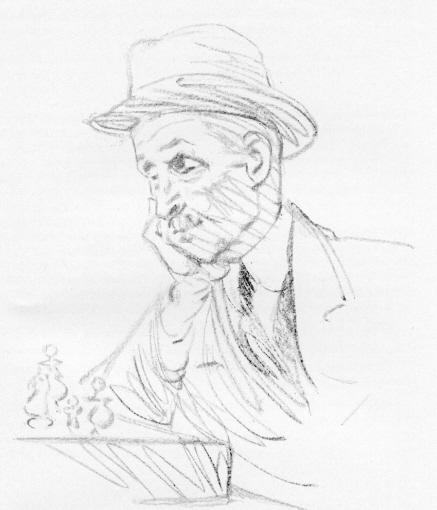

The above sketch (‘Bonar Law playing chess at the Café de la Régence in Paris, from a drawing by L. Berings, summer 1921’) was published opposite page 432 of The Unknown Prime Minister by Robert Blake (London, 1955).

Here is another game by Bonar Law, from a match in which the House of Commons faced a team from Oxford and Cambridge universities:

Andrew Bonar Law – R. Lob (Oxford)

House of Commons, London, 23 March 1909

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 f5 4 d4 fxe4 5 Bxc6 dxc6 6 Nxe5 Nf6 7 Bg5 Be6 8 O-O c5 9 c3 cxd4 10 cxd4 Be7 11 Nc3 Bf5 12 Qb3 Bg6 13 Qxb7 O-O

14 Nxg6 hxg6 15 Nxe4 Nxe4 16 Bxe7 Qxe7 17 Rae1 Nd6 18 Qxa8 Qf6 19 Qxa7 Nb5 20 Qc5 Nxd4 21 Qxc7 Kh7 22 Re3 Nf5 23 Rh3+ Kg8 24 Qc4+ Rf7 25 Rc3 Kh7 26 Rf3 Re7 27 g4 Qg5 28 Kh1 Nh4 29 Rf8 Qe5 30 Qg8+ Kh6 31 Qh8+ Kg5 32 f4+ Resigns.

Source: Times Literary Supplement, 20 May 1909, page 192. R. Lob was Oxford University’s top player at that time.

From page 9 of Bonar Law by R.J.Q. Adams (London, 1999) comes a quote about the future Prime Minister:

‘As a youth he got into the habit of carrying a miniature chess board about with him; on the train journey he made between Helensburgh and Glasgow every day except Sunday he played fellow commuters or, if no opponent presented himself, practised by himself. He eventually became a first-class amateur, competitive in play with opponents of international calibre. Bonar Law was introspective and serious even as a young man: the silent and absorbing gravity of a chess match suited him well.’

(Kingpin, 1999)

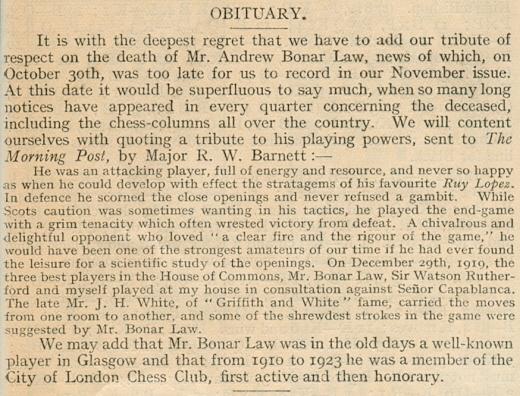

Bonar Law’s connection with Glasgow chess was mentioned in a brief report in the Morning Post which was reproduced on page 102 of the January 1923 Chess Amateur.

Andrew Bonar Law – William Watson Rutherford

House of Commons, London, December 1915

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Nxe4 6 d4 b5 7 Bb3 d5 8 Re1 Na5 9 c3 Be6 10 dxe5 Bc5 11 Be3 Bxe3 12 Rxe3 O-O 13 Bc2 Nc4 14 Re2 Nxb2 15 Qc1 Nc4 16 Bxe4 dxe4 17 Rxe4 Qe7 18 Nd4 c5 19 Nb3 Rfd8 20 N1d2 Rd3 21 Nxc4 bxc4 22 Nd2 Rad8 23 Nxc4 Bxc4 24 Rxc4 Qxe5 25 f3 Qe2 26 White resigns.

Source: The “British Chess Magazine” Chess Annual 1915 (Leeds, 1916), pages 82-84, which gave the game with Burn’s notes from The Field. The players were identified only as ‘B.L.’ and ‘W.W.R.’

(Kingpin, 2000)

K.A.L. Hill – Andrew Bonar Law

House of Commons, London, 1922

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 c5 3 c4 Nf6 4 Nc3 e6 5 Bg5 cxd4 6 Qxd4 Be7 7 cxd5 exd5 8 e3 Nc6 9 Bb5 O-O 10 Bxc6 bxc6 11 O-O c5 12 Qd3 h6 13 Bxf6 Bxf6 14 Qxd5 Qxd5 15 Nxd5 Bxb2 16 Rab1 Rb8 17 Nd2 Ba6 18 Ne7+ Kh8 19 Nc6 Rb6 20 Nxa7 Bxf1 21 Kxf1 Ra6 22 Rxb2 Rxa7 23 Rc2 Rc8 24 Ne4 Ra4 25 Rxc5 Rxc5 26 Nxc5 Rxa2 27 h4 Kg8 28 g3 Kf8 29 Kg2 Ke7 30 Kf3 Kd6 31 Nd3 Ra3 32 Nf4 Ke5 33 Ne2 Kd5 34 Nd4 Ra6 35 g4 Rf6+ 36 Kg3 g6 37 Ne2 Ke4 38 Nf4 Ra6 39 Kg2 Ra5 40 Ne2 Kd3 41 Ng3 Kd2 42 h5 Ke1 43 hxg6 fxg6 44 Kf3 Ra2 45 Ne4 Rb2 46 Kg3 Kf1 47 Kf3 Kg1 48 Kg3 Rb8 49 Nc3 Rf8 50 f4 Rc8 51 Nd5 Re8 52 Kf3 Drawn.

Source: issue 32 of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français, pages 483-484. The French magazine indicated its source as The Times (no date provided).

(Kingpin, 2001)

We are grateful to Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) for the following additional game:

John D. Chambers – Andrew Bonar Law

SCA Championship Tourney, Glasgow, April 1897

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 d3 d6 5 c3 h6 6 h3 Nf6 7 Bb3 O-O 8 O-O Kh8 9 Qe2 Nh7 10 Be3 Bb6 11 Nfd2 f5 12 Bxb6 axb6 13 f4 exf4 14 Rxf4 fxe4 15 Rxf8+ Qxf8 16 Nxe4 Bd7 17 Nbd2 Ra5 18 Nf3 Qe8 19 d4 Bf5 20 Re1 Ra8 21 Nh4 Qd7 22 Ng3 g6 23 Ngxf5 gxf5 24 Qh5 Ne7 25 Rxe7 Resigns.

Source: Falkirk Herald, 31 January 1923.

At the time of the game, Bonar Law was President of the Scottish Chess Association (BCM, May 1897, page 174).

(2773)

For a further brief feature on Bonar Law (from the New York Herald Tribune) see page 43 of the March-April 1947 American Chess Bulletin.

From page 152 of the American Chess Bulletin, July 1912:

‘Speaking against Home Rule, Mr Bonar Law said, among other things: “I don’t know whether any of you play the game of chess. I am rather fond of it myself. If any of you understand anything about it you know it sometimes happens, when two players have been engaged in a game for some time, that one of them announces mate in so many moves and his opponent examines the board, and if he sees the mate is there he surrenders the game. That is the position on the political chess board now. Mr Redmond [John Redmond, the leader of the Irish National Party] has played his game so successfully and, with the Government as sleeping partner, announces mate in three moves. But suddenly the pawns, those vigorous pawns, spring to life, and refuse to be moved by them, and insist on moving themselves, and what becomes of the nice situation then?”’

More particulars about Bonar Law’s speech would be welcomed.

(3727)

C.N. 5804 gave, courtesy of Juan Carlos Sanz Menéndez (Alcorcón, Spain), an interview with Alekhine in Semana, 26 October 1943 in which the world champion referred to having met Bonar Law (‘a very strong player’) over the board:

‘He jugado yo mismo con Bonnard [Bonar] Law, que era un jugador muy fuerte.’

From page 447 of the December 1923 BCM:

The obituary of Frederick Law Armstrong on pages 426-427 of the October 1925 BCM stated:

‘He was one of the players who, during the War, provided relaxation from heavier cares for the late Mr Bonar Law, by playing chess with him.’

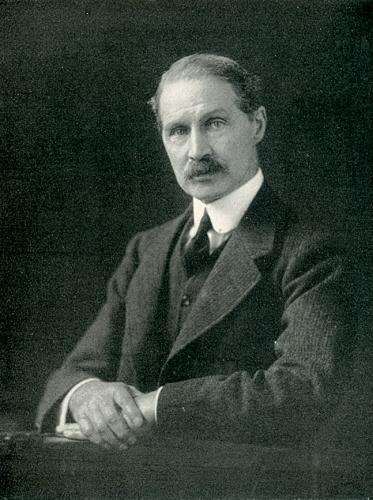

Andrew Bonar Law: photograph opposite page 58 of Chess and its Stars by Brian Harley (Leeds, 1936)

Note: Items in the present article which we originally presented in Kingpin are indicated by the letter K and the year of publication.

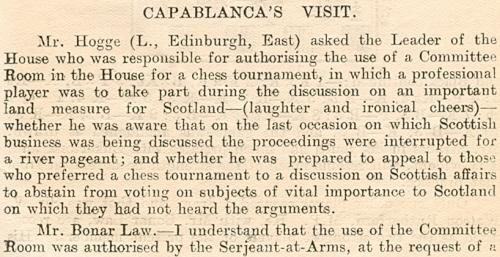

For chess-related observations on Bonar Law by Sir John Simon (including Bonar Law’s description of chess as ‘a cold bath for the mind’), see our feature article A Chessplaying Statesman. There are also a number of references to Bonar Law in Chess and the House of Commons. See too Capablanca in New York World (1925). Readers are furthermore referred to pages 113-114 of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975), and we conclude with an item from pages 9-10 of the January 1920 BCM regarding a parliamentary question to Bonar Law (then the Leader of the House) arising from Capablanca’s simultaneous display in Committee Room No. 14 of the House of Commons on 2 December 1919:

See too C.N.s 11626 and 11682. From the latter item:

A grievance was expressed by James Myles Hogge (1873-1928), the Liberal MP for Edinburgh East.

The Hansard record shows that the BCM gave only an abridged account of the exchanges between Hogge and the Leader of the House, Andrew Bonar Law.

Reproduced with authorization:

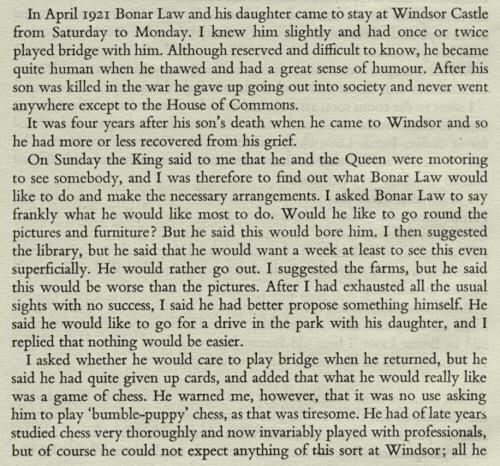

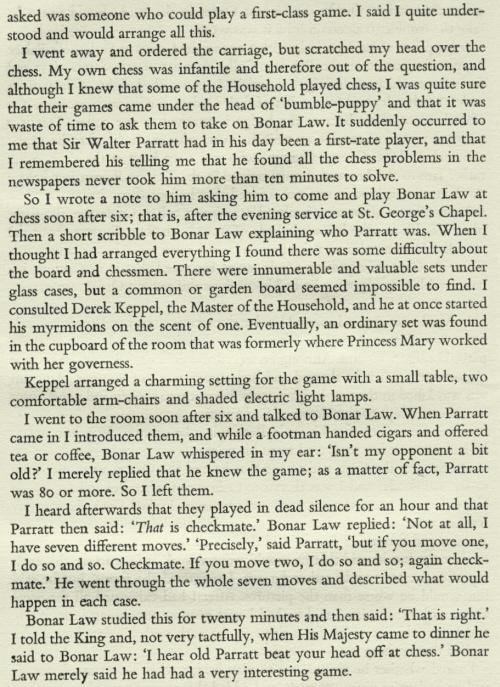

Pages 353-354 of Recollections of Three Reigns by Sir Frederick Ponsonby (London, 1937) relate an episode concerning Bonar Law, Sir Walter Parratt and King George V:

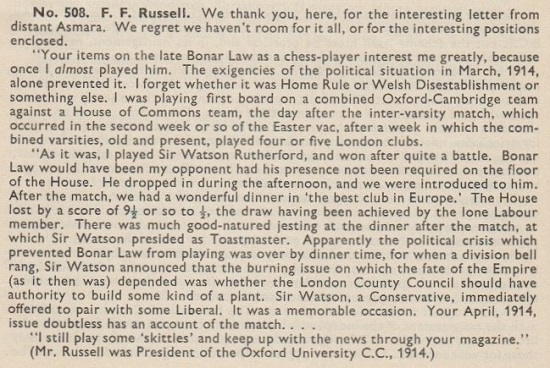

Page 59 of the March 1957 BCM (in the Quotes and Queries column by D.J. Morgan) quoted a contribution from F.F. Russell:

On page 229 of the September 1957 issue the result of the Oxford/Cambridge v House of Commons match was given, courtesy of Kenneth O. Morgan, from page 13 of the Times, 25 March 1914. The contest had taken place the previous day.

Alan McGowan submits a cutting about Andrew Bonar Law from the chess column in the 19 October 1921 edition of the Falkirk Herald, page 4:

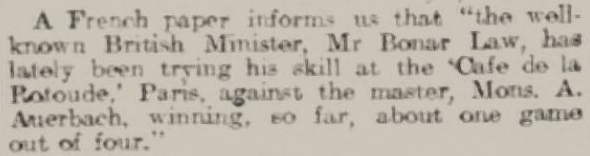

The establishment in Paris, mentioned in C.N. 10114, was the Café de la Rotonde au Palais-Royal.

Regarding the Bonar Law Trophy, see, for instance, page 204 of the May 1927 BCM.

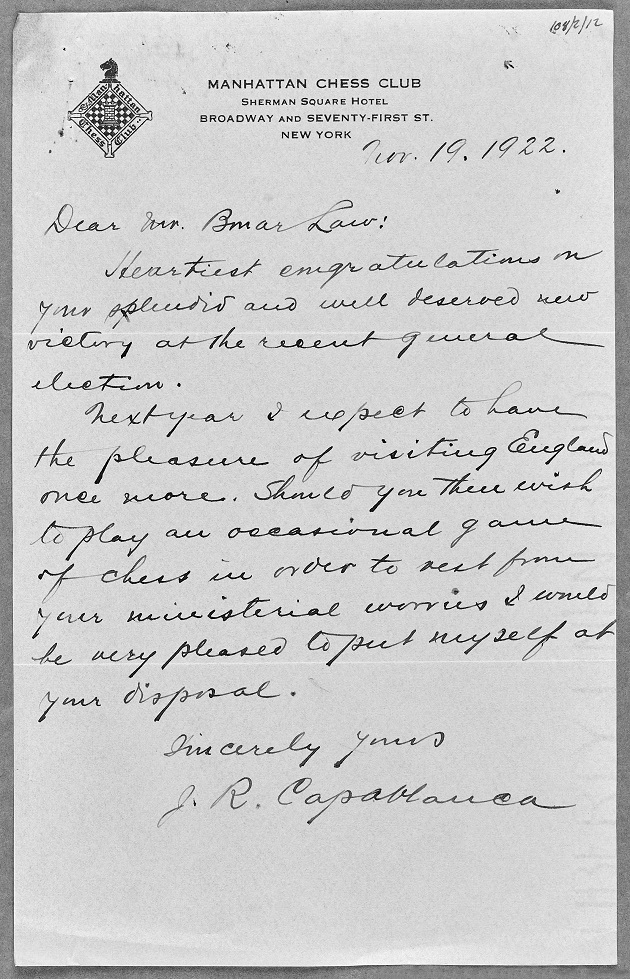

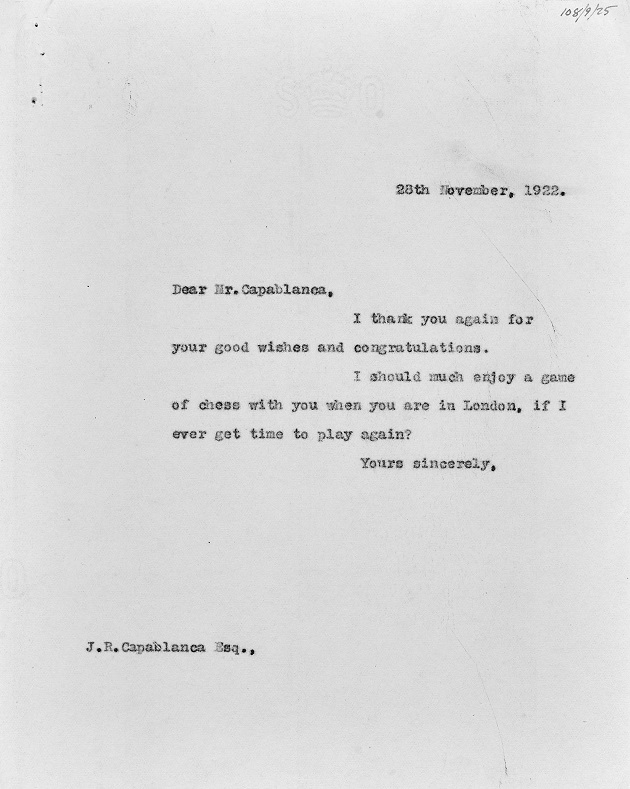

Permission for us to reproduce an exchange of letters between Capablanca and Andrew Bonar Law has been obtained by Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) from the UK Parliament Parliamentary Archives:

One of Andrew Bonar Law’s brothers, John R. Kidston Law, was also a chessplayer, as noted in his obituaries on page 334 of the October 1919 BCM and on page 3 of the October 1919 Chess Amateur.

Gerald Abrahams discussed Andrew Bonar Law, William Watson Rutherford, John Simon and Richard Barnett on pages 37-38 of Not Only Chess (London, 1974):

Addition on 9 February 2025:

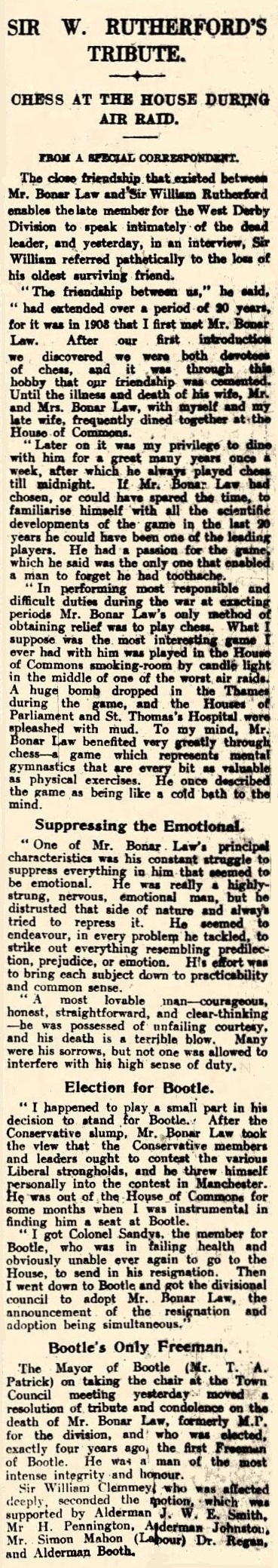

From page 6 of the Liverpool Post & Mercury, 1 November 1923:

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.