Edward Winter

Brentano’s Chess Monthly, June 1881, page 67

Note on 29 January 2023: The present article has been augmented with C.N.s 2401, 2613, 7575, 9376, 11208 and 11593 to illustrate the topic of ‘rude’ book reviews.

**

Remarks by F.M. Teed on page 109 of the May 1886 International Chess Magazine:

‘Chess reviewers, as a rule, are so indiscriminately laudatory that conscientious criticism is likely to be regarded as theh work of a malevolent, splenetic and generally unpleasant individual, yet such ought not to be the case. It is an easy matter to write a gushingly favorable notice of such a book as this [Chess-Nut Burrs], if one elect to dilate on its best features, and to pass over its imperfections. Anyone can ring changes on “elegant typography”, “choice collection of gems”, “the best work of the best workmen”, “terse and incisive diction”, or like conventional phrases; but that is a kind of writing that signifies nothing, as a rule.’

Today one can easily think of countless editors and columnists who should read and heed Teed’s creed.

(1075)

Addition on 23 April 2024:

A singer unable to sing is pilloried. A writer unable to write is indulged.

Reviewing The Major Tactics of Chess by Franklin K. Young, the BCM (March 1899, page 99) expressed some excellent sentiments on book reviews in general:

‘... In these rapid times, ostensibly intricate matters are not liable to much contradiction, even where there is more than a small suspicion of error; few who really examine them caring to openly dissent from the most doubtful conclusions, when these are cast in all the imposing dignity of print. Thus readers (and reviewers too) favour the temerity of authors, and help to mislead the public, including of course themselves – the simple, good-natured, omne-ignotum-pro-mirifico public; the great present and future public, which can never be too well or honestly served.’

(1414)

The approach of E.G.R. Cordingley to book reviewing was set out on page 174 of The Chess Students Quarterly, December 1947:

‘If I appear a poor encomiast, it is because in reviewing a book I judge whether, within the compass of its pages and its title, the author has made the most of the material available and presented a balanced, interesting work; but I am not content with a book being merely good, and interesting, and competent – I must ask myself in what way might it be better, more interesting, more enlivening to the curious, inquisitive, seeking mind of an intelligent chess player; for, after all, a reviewer’s function is not to advertise the publishers’ wares but to give a frank, objective opinion upon a book; to offer constructive suggestions; to discourage careless writing, or indifferent supervision by the publisher; and, in general, to help in maintaining a high standard of book-production.’

For fastidiousness Cordingley was a nonpareil. Here are some of his criticisms of Golombek’s book Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess:

‘In one respect Golombek has been inconsistent, but he followed in the steps of countless generations of annotators: he uses the Present, Past, and Future Past Perfect tenses for actions that should enjoy a common tense. In one game the notes are in the Present, in another the Past, and in a third in the mood of the moment, vacillating with carefree abandon betwixt past and present, with occasionally a false sequence within a sentence for sweet variety’s sake. … In game 81 will be found “is”, “was”, “would be”, “would have been”, – need the argument be carried further?

… One other comment I feel forced to make, the extraordinary use made of the semicolon, here a servile lackey to the colon and full stop. It is used to replace the colon, whose specialized use is clearly defined, and to join two sentences having no connecting thought. I suspect the compositor of having a hand in this ill usage of the half stop, for the narrow two inch column probably does not ease the art of justifying the margins.’

Source: The Chess Students Quarterly, June 1947, pages 106 and 110.

(Kingpin, 2000)

An arraignment by Harry Golombek on page 7 of the January 1939 BCM, i.e. the opening paragraph of a review of Lehrreiche Kurzpartien by J. Benzinger (Leipzig, 1938):

‘This book contains a collection of 172 brief games only about four of which ever deserved to be seen in print. The rest are feeble examples of third-rate chess. Miniature games of chess should resemble miniature paintings; they should be delicately varied, subtly designed and, above all, executed with economy. But these are gross, heavy and thick with accumulated blunders, in short the book is a chamber of horrors which contains but little of the edification promised in the title.’

(2401)

C.J.S. Purdy was in cracking form on page 43 of Chess World, 1 February 1950:

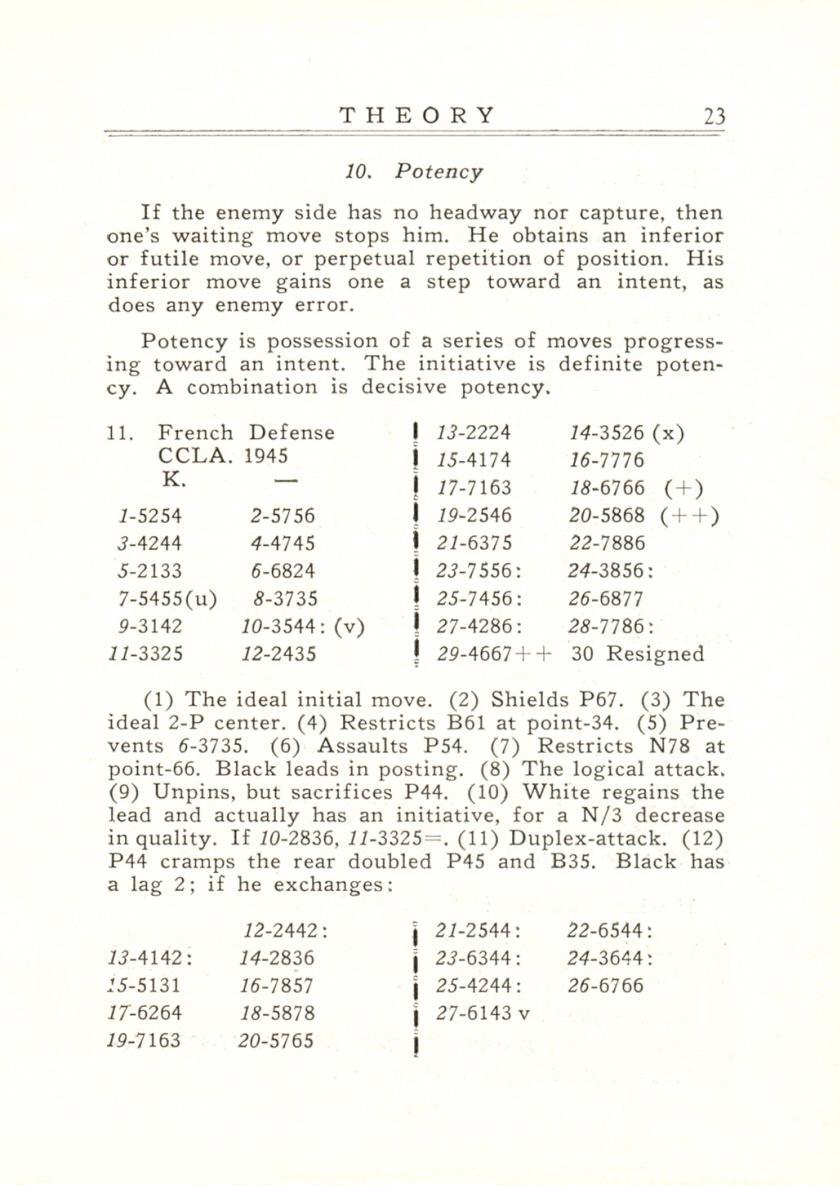

‘Chess Logic (sic) is by B. Koppin of the USA – that’s all the address given. The book gives the impression that the author knows what he is talking about; but it is a secret which the reader does not share. We quote here from the book’s second part, entitled “Theory”:

“Power, or intrinsic ability, consists in strength and its extension. Strength consists in quality and safety. Extension consists in space, interference, force, and potency. A strong, extended man or side is powerful. – Advantage, or extrinsic ability, is the difference in powers. It is received from the enemy. It readily changes in kind, but not degree …

Posting is an improvement of space and interference … A side with post equality at his turn to move, has a posting lead 1. In a perfect opening a side’s attainable, additional posting becomes zero …

Potency is possession of a series of moves progressing towards an intent. The initiative is definite potency. A combination is decisive potency …

If powers are even and a win can evolve, then play continues. A man’s power can be high, normal, low, none or detrimental, because of its location or presence.”

This book will be permanently available for inspection at our office.

We believe the author’s statement that he has master rating in the International Correspondence Chess Association, but only because he says so in the preface. The book is called Chess Logic, for Beginner and Master. Truly the beginner and the master may read it with equal safety; neither should suffer bodily harm. It consists of 45 octavo pages. It is well printed. But why was it printed?’

(2613)

(2613)

How quaint such comments seem in today’s more hectic era.

(3779)

On 5 September 2005 András Adorján (Budapest) wrote to us:

‘95% of opening books are rubbish – many of them are made in two to three weeks by using two to three books written earlier. I also say that 95% of reviewers do not bother actually to read the book they are going to write about. Having all (?) the reviews of my newest BLACK is still OK! and BLACK is OK forever!, I can prove it too.’

(3914)

In Historical Havoc we observed:

When poor books appear, few people utter a word of protest, for it takes longer to prepare a diligently negative review than a few bromidic compliments. Censuring a writer for inflicting a feeble or unnecessary book on the chess world may be reckoned bad form, as if unquestioning gratitude were due to all who do our game the honour of writing about it, no matter how unequipped for the task they may be. Eminent film critics have a more fastidious approach: they judge whether a production is a masterpiece and, if it is not, they bluntly explain why. In chess that would appear absurdly rigorous, not to say churlish and pedantic.

See too Over and Out, where we commented in particular:

How easy it is to be a book reviewer, yet how difficult to be a good one.

A famous quip attributed to Adlai Stevenson (1900-65):

‘An editor is one who separates the wheat from the chaff and prints the chaff.’

Quotations books also have this remark by Elbert Hubbard (1856-1915):

‘Editor: a person employed by a newspaper, whose business it is to separate the wheat from the chaff, and to see that the chaff is printed.’

We note, though, an observation on page 3 of the Westminster Papers, May 1869, in a demolition of The Book of Chess by George H. Selkirk (London, 1868):

‘His compilations are singularly crude and valueless; indeed they seem to have been conducted on the principle of carefully sifting the wheat from the chaff and retaining the chaff.’

(6579)

On page 4 of the Westminster Papers, the review adds that G.H. Selkirk ‘unblushingly inscribes on his title page “The Book of Chess”’, and concludes:

‘“The Book of Chess” attached as a title to such a farrago of milk-and-water plagiarism and feeble platitudes, reminds us irresistibly of “History of England” on the back of our grandmother’s backgammon board. The parallel is perfect – both externally and internally.’

C.J.S. Purdy’s comments on the book Chess Logic For Beginner and Master in C.N. 2613 above are reminiscent of the parting shot in a review of G.H.D. Gossip’s The Chess Player’s Manual on pages 84-88 of the Westminster Papers, 1 September 1874:

‘In conclusion, we must mention the exterior of the book: paper and print are first-rate, but the merits of the publishers cannot compensate for the incapacity of the author.’

The review also remarked (on page 84):

‘The pages 27-34, containing the Laws of the British Chess Association, are the only pages in the book without blunders, at least blunders which can be attributed to the author.’

The following issue (1 October 1874, pages 105-106) of the Westminster Papers, which was edited by P.T. Duffy, related that a letter ‘of 11 closely written pages’ had been received from Gossip but that ‘we do not share with Mr Gossip the opinion that the public are expecting a reply from him’.

G.H. Diggle referred to the episode on pages 1-2 of the January 1969 BCM, in his article on Gossip, ‘The Master Who Never Was’:

‘This contemptuous and indeed unfair treatment would have flattened a man less courageous, and less wrong-headed, than its victim, especially as other reviews, though not so venomous, had been scarcely more favourable. Indeed, when the general chorus of groans had died down, it was thought that Gossip as an author had been disposed of for good. But suddenly in 1879 (after five years’ obscurity in the “doghouse”) he made a fighting recovery with The Theory of the Chess Openings ...’

(7575)

From W.N. Potter’s review of Chess Chips by J. Paul Taylor (London, 1878), on page 129 of the Huddersfield College Magazine, February 1879:

‘Beginning with the Preface, I think I must congratulate the author upon its brevity. Prose composition is evidently not his strong point, and therefore he is wise not to attempt much in that line.’

(9376)

Do readers know of any magazines or websites which, systematically and comprehensively, produce authoritative reviews of new chess books?

‘Authoritative’ excludes all those easily pleased outlets making do with superficial impressions which could be written by virtually anybody. For example, a reviewer who praises The Joys of Chess by C. Hesse (Alkmaar, 2011), not realizing that it is unreliable and makes excessive, insufficiently credited use of earlier writers’ work, is unqualified to review books in, at the very least, that category. A reviewer of a new openings monograph needs proper knowledge of what has already been published on the same opening. A reviewer who imagines that all McFarland books (even the Steinitz biography by K. Landsberger) merit indiscriminate eulogies has no business publicly assessing works about chess history. Plaudits are deserved by many McFarland titles, but not all, and it is the critic’s task to make the requisite distinctions. A reviewer whose own volumes are notorious for blunders and other defects (plagiarism, for instance) should be neither reviewing nor authoring. Nor, of course, should any writer wish to quote favourable opinions received from such a reviewer. T. Harding rushing to cite R. Keene’s fulsome praise of his Blackburne book was a pathetic spectacle.

Some people are qualified to evaluate no chess books of any kind, but nobody is qualified to evaluate the full range of the game’s literature. C.N. 3766 referred to the skill of Brian Reilly, as editor of the BCM, in bringing together a team of excellent book reviewers which included J.M. Aitken, W.H. Cozens, G.H. Diggle, W. Heidenfeld and D.J. Morgan, each with his specialities.

It is relevant to recall the words of W.H. Watts on page 115 of the March 1933 BCM:

‘It has long been a grievance of mine that so far as chess books are concerned the art of reviewing has almost entirely disappeared. It seems that Editors imagine book publishers send copies of their new publications solely to get the little bit of publicity which a favourable puff will provide, and are averse to any form of criticism. Either this, or books are reviewed by writers not sufficiently qualified to criticize, or who do not know what a book review is. I remember in my early days book reviewing was taken quite seriously, and choosing reviewers for important books was a task requiring the most careful consideration. Editors took great care to see that books had adequate and suitable attention, and in no case would the trite clichés which now pass as reviews be accepted. “Well printed”, “On good paper”, “Many and very clear diagrams”, “Profound analysis”, “A splendid selection of brilliant games”, with a few other stock phrases similarly pleasant, culminating in “No chessplayer’s library is complete without it” exhaust almost every review of a chess book that has appeared for many years.

How different it was in the past. Comparatively speaking Chess Blossoms by Miss F.F. Beechey is a very unimportant book, and yet in the Chess Player’s Chronicle of 1883 no less than four pages were devoted to its review. This review is a critical examination of the contents, and is what I with my old-fashioned ideas always imagined a review had to be. The review of Horwitz and Kling’s End Games occupies two pages of the CPC for May 1884, and I could multiply these instances many times by reference to early issues of the BCM itself. It must happen occasionally that the most important chess event of the month is the publication of some new book on the game, and yet it gets but scant notice, on the lines indicated, and henceforward passes into oblivion.’

A chess publisher supplying review copies can be hopeful of an enthusiastic write-up, with or without cronyism and with or without thought. The very existence of chess titles produced by non-chess publishers may be overlooked. To take specific cases from recent years, below are three hardbacks, Birth of the Chess Queen by Marilyn Yalom (New York, 2004), Power Play by Jenny Adams (Philadelphia, 2006) and Ivory Vikings by Nancy Marie Brown (New York, 2015).

The third of those books has only just appeared, but which chess magazines and ‘review websites’ have offered their readers authoritative assessments of the earlier two works? And, lest all this be considered too arcane, to which magazines or websites can a reader turn when wishing to buy a book about Magnus Carlsen and seeking dependable, objective guidance on which ones are excellent, good, bad and awful from among the dozen or so titles available?

(9592)

The observation at the start of C.N. 9592 above, concerning the ‘pathetic spectacle’, prompts a question: is there any chess writer less McFarlandish than Raymond Keene?

As shown on page 38 of volume two of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1987) G.H. Diggle wrote in the April 1986 Newsflash:

‘In the June 1887 BCM is a review of H.E. Bird’s Modern Chess, Part V, a shilling booklet of 36 pages devoted entirely to the Evans Gambit. Yet the reviewer, Edward Freeborough, devotes seven pages to dissecting Bird’s analysis, winding up however on a cheerful note: “... the student will certainly not be dissatisfied with his shilling’s worth. There is plenty of provender: he must supply his own digestive organs.”’

(9636)

‘The man who criticizes books which tend to be scientific or literary is paid badly. Consequently no-one is induced to make a serious study of the act of criticism, with the result that much passes for great that is merely mediocre, and that the mediocre is praised beyond merit.’

Source: The Community of the Future by Emanuel Lasker (New York, 1940), page 181.

(10525)

Below is one of several barbs by Ed Edmondson when reviewing R.G. Wade’s Soviet Chess (London, 1968) on page 108 of Chess Life, March 1969:

‘Not recommended if your budget for chess books is at all limited. It’s one man’s opinion, but I consider this volume to be only for those who can truly afford to satisfy their own curiosity about its dullness or to acquire a collection of chess books regardless of quality.’

Another man’s opinion was on pages 58-59 of the February 1969 BCM, where one of the greatest of all chess book reviewers, W.H. Cozens, expressed some criticism of Soviet Chess but also praised it highly, concluding:

‘It would be hard to suggest how any serious student of chess could find a better use for two guineas.’

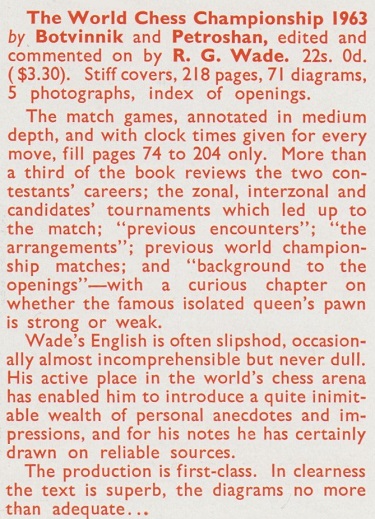

A brief notice of another book by Wade comes to mind, from the inside front cover of CHESS, mid-January 1964:

(11208)

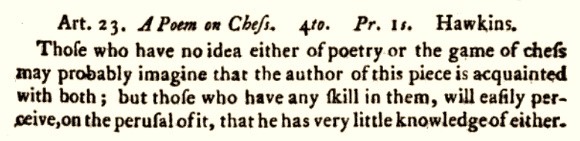

On the topic of rude book reviews, William Hartston (Cambridge, England) submits the oldest specimen that we have been able to give so far, from page 237 of the March 1764 edition of the Critical Review, concerning A Poem on Chess by Guy Hawkins:

‘Those who have no idea either of poetry or the game of chess may probably imagine that the author of this piece is acquainted with both; but those who have any skill in them, will easily perceive, on the perusal of it, that he has very little knowledge of either.’

(11593)

Addition to Chess Thoughts on 9 May 2025:

A docile book reviewer is usually more biased than a critical one.

Why do almost all chess reviewers like almost all chess books?

(12168)

See too various C.N. feature articles and, in particular, The Chess Chamber of Horrors and the list of webpages at the conclusion thereof. Regarding the shortest book reviews, see C.N.s 3480, 3794 and 3798.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.