Edward Winter

From the entry on G.H.D. Gossip in The Oxford Companion to Chess:

‘He had an unusual talent for making enemies. In his later years Steinitz had the same problem but claimed at the end of his life that he had six chess friends. Gossip had none.’

The grounds for the statement about Gossip are unknown to us, but the other remark seems to be based on R.J. Buckley’s reminiscences about Steinitz referred to in our Chess with Violence article:

‘We never quarrelled. Colonel Showalter [at the London, 1899 tournament] said that he and I were the only exempts. To which Steinitz replied, “No, there are four more, six altogether. From any one of those six I would accept a cigar, and from none other”.’

This was one of three chess articles by Buckley that were to have a particular impact. Another concerned the 1910 Lasker v Schlechter match, the terms of which are an unsolved and probably insoluble mystery. One aspect of the controversy is whether the world championship title was at stake. David Hooper stated on pages 183-184 of the March 1976 CHESS that he did not believe so, and one of his paragraphs read:

‘The American Chess Bulletin, 1910, page 155 writes: “the champion agreed to play a series of games, but it was expressly stipulated that the result was not to touch the title”. I have almost a complete run of this magazine, which Lasker read, and on all other occasions when a comment was published which in any way touched his honour he replied at once: yet on this one occasion he made no comment at all.’

David Hooper was referring to an article by Buckley on pages 155-156 of the June 1910 American Chess Bulletin, but the above-quoted reference to Lasker leaves us flummoxed because a rebuttal by the then world champion was reported within the article itself. [See C.N. 3252 below.] The full text of the relevant passage from Buckley’s article, with the Bulletin Editor’s interjection, is as follows:

‘The result of the late match points to a contest on different terms, a match for the world championship. The ten games lately played constituted a sort of match, but the object was not the settlement of the championship, as many have supposed. If Schlechter had won all the games, Lasker would still have been titular world champion. The champion agreed to play a series of games, but it was expressly stipulated that the result was not to touch the title.

This consideration affects opinion of the result.

(In reply to a query on board the SS Vasari, on 20 May, Dr Lasker, southward bound, said, “Yes, I placed the title at stake”; thereby confirming our understanding of the matter. Notwithstanding this, we can well believe that, owing to the unusual circumstances of the match, many people would have continued to regard Dr Lasker as champion, even had he lost that final game. Ed., ACB.)’

The biggest stir caused by an article of Buckley’s came after the death of James Mason in 1905. Buckley wrote in his Birmingham Weekly Mercury column (15 April 1905, page 25):

‘And here I may tell the world something which has not before been hinted, either in print or, so far as I know, in any other way.

James Mason’s true name was neither James nor Mason. His real name was confided to me years ago, as it were, sub sigillo confessionis.’

For further details see page 191 of the April 1905 American Chess Bulletin, page 11 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, May 1905 and C.N. 1673. An extensive article by Jim Hayes was published on pages 10-15 of the March 1997 CHESS.

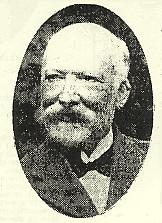

Robert John Buckley

The contribution to chess literature of Robert John Buckley (who was born in Ireland in 1847) essentially amounted to his articles for the local press, which occasionally reached a wider audience. ‘Robert J. Buckley – Chess Philosopher’ was the heading of a three-page spread in the March 1907 American Chess Bulletin (pages 52-54), introduced as follows:

‘When in philosophical humor, a mood that is apt to become habitual when long indulged in – Robert J. Buckley, to whom the Birmingham Illustrated Weekly Mercury is indebted for regular contributions on chess, is one of the most entertaining writers known to the royal game. Thanks to a ripe experience which dates back to the time of Zukertort and McDonnell [sic], not to mention a genius for presenting his logic in a clear-cut and convincing style, his musings, set in choicest English, are at once instructive and thought-compelling.’

Below are two excerpts from the Buckley material presented by the Bulletin:

‘The greatest players are those who to great accuracy add great imagination. Blackburne at his best was more imaginative than accurate. He out-imagined the strongest players by the score. Steinitz was highly imaginative and also accurate. So is Dr Lasker. So was Morphy. Though a mathematician, Anderssen’s imagination was, perhaps, slightly in excess of his accuracy. The accuracy of Dr Tarrasch is his strong suit; of imagination one discovers hardly a chemical trace.’

‘Morphy was a revelation. Steinitz was a revolution. Lasker is an advance on Steinitz. He borrows from all and imitates none. Having assimilated the best of all the schools, he produces something unlike any; in our opinion, fundamentally superior to any.’

A characteristic specimen of Buckley’s light reportage was written during the Lasker v Blackburne match in London in 1892 for the Birmingham Mercury and was subsequently reproduced on pages 115-116 of The Chess Bouquet by F.R. Gittins (London, 1897). Below is an extract:

‘The great match was postponed for three days, owing to Blackburne’s indisposition, and we were at the British Chess Club on the faith of an announcement made on Monday morning that play would begin at 2.30 precisely. We arrived at midday, and were considerably taken aback at the unexpected news.

But we immediately adjourned to Simpson’s Divan, and there received a very hearty welcome. The Grand Old Man beamed radiantly, and all creation smiled. Lasker relaxed his disappointed look, and for the moment seemed consoled. Van Vliet stretched forth the fellowshipial hand. F.J. Lee looked as if he might be happy yet. Even Jasnogrodsky seemed pleased, and for a moment the settled melancholy which is supposed to arise from the burden of his name was chased away. Tinsley smiled the broadest, but then he learned his manners in the country, where people are too unsophisticated to conceal their joy.

It was indeed a memorable moment. Loman was deeply engaged in the Handicap Tourney, but even he found time to bestow a greeting on your humble representative. James Mason emerged from a dark and remote corner, where he hides from the light of day, and engaged us in animated conversation. Müller, who has foresworn chess and has determined to become a millionaire in some other way, warmly gripped the editorial fin. It was clear that something ought to be done. We challenged Lasker, offering to concede to him the odds of the rook. He declined the gage of battle. Perhaps this was best. We have no desire to ruin the reputation of the young. He may have wanted the queen. Mr Bird rushed into the breach and, lifting the gauntlet, cast defiance at our head. The metaphor is not so mixed as we could wish, but no matter.’

Later in the article Buckley wrote concerning one of his skirmishes with Bird, ‘The next game was a Muzio, in which we sacrificed several pieces, emerging with an excellent position, but no men’.

Mason’s Social Chess (London, 1900) presented three games won by Buckley, without dates, venues or opponents’ names:

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 Nc3 e5 4 Bc4 Nc6 5 d3 Nge7 6 Bg5 Bg4 7 Nd5 Nd4 8 Nxe5 Bxd1 9 Nf6+ gxf6 10 Bxf7 mate. (This game is normally said to have been won by H.T. Buckle in 1840. At which stage confusion may have arisen between the names Buckle and Buckley has yet to be learned.)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ng5 h6 6 Nxf7 Kxf7 7 d4 d5 8 Bxf4 Bg7 9 Nc3 dxe4 10 Bc4+ Be6 11 d5 Bf5 12 d6+ Be6 13 Bxe6+ Kxe6 and White announced mate in four moves (14 Qd5+ Kf6 15 Nxe4+ Kg6 16 h5+ Kh7 17 Qf5). (One of 15 games played simultaneously, according to Mason’s book.)

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 exf4 4 Nf3 g5 5 h4 g4 6 Ng5 h5 7 d4 f6 8 Bxf4 fxg5 9 Bxg5 Be7 10 Nd5 Bxg5 11 hxg5 Nge7 12 Nf6+ Kf8 13 d5 Ne5 14 d6 cxd6 15 Qxd6 Nc6 16 Nd5 Rh7 17 Bc4 Na5 18 O-O+ Kg8 19 Nxe7+ Kh8 20 Qf6+ Rg7 21 Qh6+ Rh7 22 Ng6 mate. [In C.N. 3743 Alan Smith (Manchester, England) reported that Buckley published the game in the Manchester City News of 30 May 1908, where he specified that it was played at Simpson’s Divan in London ‘sometime in the 1880s’ in a match against an Austrian player named Ott which Buckley won 6-0.]

Robert John Buckley

Buckley wrote on many subjects apart from chess. The Chess Bouquet observed:

‘… perhaps his greatest work is Ireland as it is and as it would be under Home Rule (Birmingham Daily Gazette, 5s).

In 1893, when the Home Rule question was agitating the minds of millions of British subjects, Mr Buckley, heedless of personal danger, visited the various scenes of the conflict, and in a brilliant series of 62 letters completely demolished Mr Gladstone’s pet project …’

The title page did not name Buckley as the author, merely referring to ‘the Special Commissioner of the Birmingham Daily Gazette’, although the three-page Preface was signed ‘R.J.B’.

His authorship of Ireland as it is was mentioned on the title-page of a novel published circa 1902, The Master Spy:

Another great interest of Buckley’s was music, and in 1904 he wrote a biography of Sir Edward Elgar, whom he knew personally. From page 29:

‘It was in the “Black Knight” period [i.e. circa 1893] that I first visited the composer at “Forli”, a charming cottage under the shadow of the Malvern Hills …’

His chess writing continued but was seldom seen beyond local newspapers, an exception being an article entitled ‘Blackburne and Winawer’ on pages 43-44 of the February 1923 American Chess Bulletin.

The Evening Despatch of 24 August 1935 (page 6) reported:

‘Now Mr Buckley, who retired from active work in 1926, and has continued the “Arley Lanes” [his non-musical writings] mainly as a means of keeping in touch with the papers he has served during the greater part of his life, feels that in his 89th year he must break this last thread.

A severe fall some months ago placed him under doctor’s orders, and it is considered advisable that in future he should devote himself entirely to the books and music which still form his principal interests.’

A very rare mention of him in the BCM came on page 417 of the August 1937 issue:

‘Information having been received at the Blackpool Chess Congress that Robert J. Buckley, of Moseley, Birmingham, would be 90 years of age on 14 July, and, in consequence, a birthday greeting card signed by one or two officials and others was sent to him. Years ago Mr Buckley was particularly well known. He was, for a very long period, chess editor of the Manchester City News, and interested in chess in various ways.’

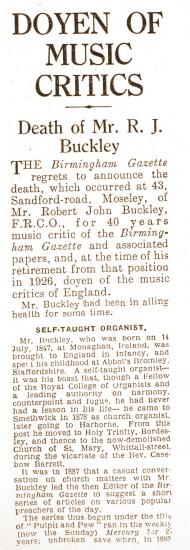

As far as we are aware, no chess periodical recorded Buckley’s subsequent demise. The Birmingham Gazette of 27 December 1938 (page 4) reported under the heading ‘Doyen of Music Critics – Death of Mr R.J. Buckley’:

‘The Birmingham Gazette regrets to announce the death, which occurred at 43 Sandford-road, Moseley, of Mr Robert John Buckley, FRCO, for 40 years music critic of the Birmingham Gazette and associated papers and, at the time of his retirement from that position in 1926, doyen of the music critics of England.

Mr Buckley had been in ailing health for some time.

Mr Buckley, who was born on 14 July 1847 at Monaghan, Ireland, was brought to England in infancy, and spent his childhood at Abbot’s Bromley, Staffordshire. A self-taught organist – it was his boast that, though a Fellow of the Royal College of Organists and a leading authority on harmony, counterpoint and fugue, he had never had a lesson in his life – he came to Smethwick in 1878 as church organist, later going to Harborne …

…In 1893 Mr Buckley was sent to Ireland as special correspondent of the Gazette during the Gladstone Home Rule troubles. The brilliant series of articles he sent back during six months, and which powerfully influenced national politics, made his reputation.

…He was also a prolific contributor of special articles to newspapers all over the country and conducted chess columns at various times in Birmingham, Manchester, Sheffield and Liverpool journals.

In 1933, his resignation from the chess editorship of the Manchester City News was signalized by a presentation from solvers of many years’ standing – many of whom had never met Mr Buckley in person.

In addition, he was the author of a volume of short stories, three novels and the first – and still standard – life of Sir Edward Elgar, who was an intimate personal friend.’

(3249)

Earlier in the year the Sunday Mercury had published the following on page 4 of its 24 July 1938 edition:

Our item above on Robert J. Buckley did, by omission, an injustice to Louis Blair, as we had forgotten that in an October 1989 letter to us he pointed out the discrepancy (to use no stronger word) between the American Chess Bulletin’s 1910 item and David Hooper’s reference to it in CHESS (1976). Mr Blair also discussed the matter in an article entitled ‘The Lasker-Schlechter match: a new look at the published evidence’ on pages 48-55 of the February 1990 BCM.

Robert John Buckley

(3252)

From the chess column of R.J. Buckley in the Birmingham Weekly Mercury of 15 April 1905, page 25:

‘A curious and apparently contradictory feature in James Mason’s character was his interminable patience. Racially, Mason was of the most impatient, the most impulsive, the most hot-headed temperament in Western Europe. Mason was a Kelt of the Kelts, a really Irish Irishman, and not in the smallest fragment of his being, one of the Scots-Irish or the Anglo-Irish who dominate Ulster.

And here I may tell the world something which has not before been hinted, either in print or, so far as I know, in any other way.

James Mason’s true name was neither James nor Mason. His real name was confided to me years ago, as it were, sub sigilla confessionis. Later he wrote:

“My father adopted the name of Mason on landing in New Orleans when I was 11, his object being avoidance of the prejudice which obtained against the Irish. Don’t split on me till I’m dead, and even then I would rather you didn’t give the name, it’s so infernally Milesian, and they’d say that all the faults of the race went with it, particularly love of drink and laziness. I have them both myself!”

The real James Mason was unknown and incomprehensible to the huge majority of the people with whom he associated, and their estimate of him, their measuring his bushel by means of their pint-pots, is ludicrous indeed. It may be that in the time to come this column may present a few extracts from Mason’s letters, of which about 400, some of them very long, regular essays, addressed to the writer, are available.

Mason was a great letter-writer, and when addressing people with whom he was in sympathy, was apt to let himself go.

And thus I have strayed from the subject of Frank Marshall to one of the “sceptred heroes who still rule our spirits from their urns”. No matter. The Masonic secret should be interesting. Perhaps Mason had other confidants. Yet he was never one of those who wear their hearts on their sleeves for daws to peck at.

One thing I wish to place on record. In money matters; in straightness; in all things where honour was a factor, I ever found James Mason the very soul of integrity; and in this respect as well as intellectually, immeasurably superior to some of the men who smiled upon him patronizingly, and held him in contempt because of his poverty and the well-known weakness which all his friends deplored.’

James Mason

There is an article about James Mason by Jim Hayes on pages 10-15 of the March 1997 CHESS. On the basis of detailed research in Kilkenny, Ireland, where was Mason was born, Mr Hayes attempted to solve one of chess history’s most enduring mysteries: what was James Mason’s real name? Although ‘absolute final proof’ was admitted to be lacking, he expressed the view that there was ‘overwhelming evidence in favour of him being Patrick Dwyer’.

An excerpt from Buckley’s chess column in the Birmingham Weekly Mercury, 25 August 1906, page 3:

‘What has the sensational exhibition to do with beautiful chess?

Why this craving for the red fire, the jugglery, the purposeless mental acrobatism that was fatal to Pillsbury? The desire for such exhibitions denotes a low level of intelligence.

Why should civilized chess amateurs exhibit the tastes of the bricklayer’s hodman or the British farm labourer?

Let the blindfold business die with poor Pillsbury. If another great chess master should arise in America, let him not be “butchered to make a gobe-mouche holiday”.’

Page 76 of the March 1918 American Chess Bulletin reported the death of ‘Lieut. Hugh Welch, of the A Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps, who was killed on 28 March last [1917] in an air fight over Lille, just before his 21st birthday. Lieut. Welch, a young man of the greatest promise, was the favorite grandson of Robert J. Buckley, chess editor of the Manchester City News, from whose facile pen have come generous contributions to the current chess literature that counts’.

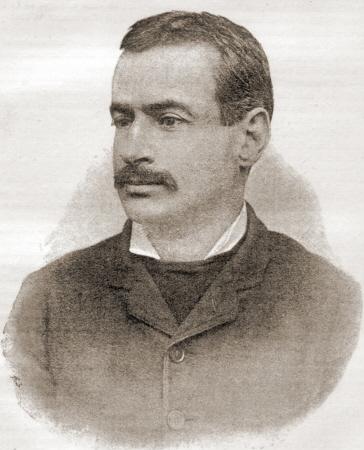

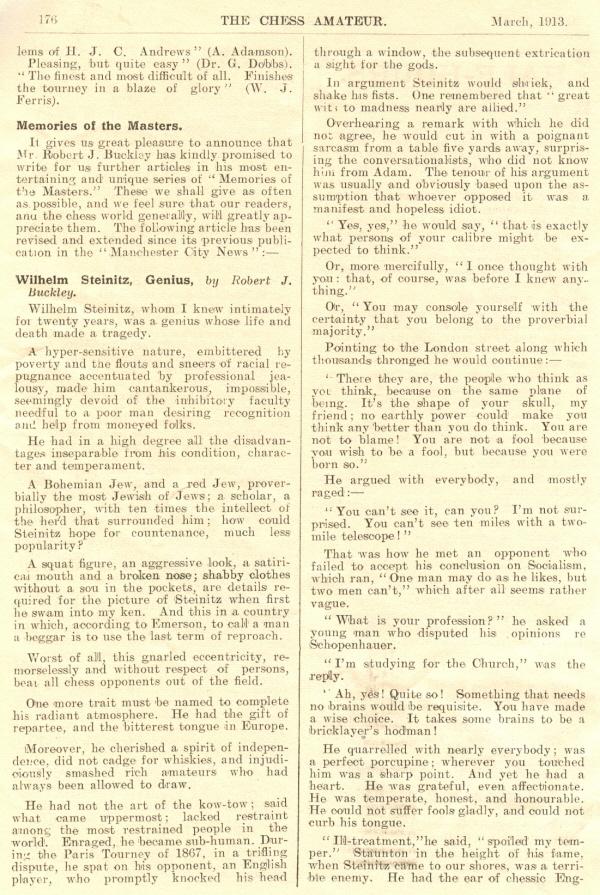

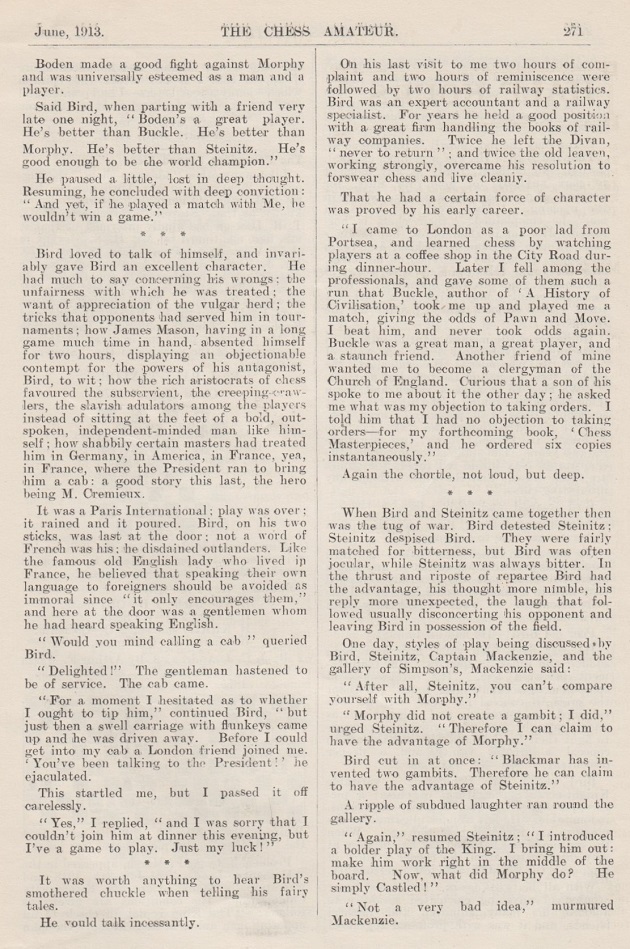

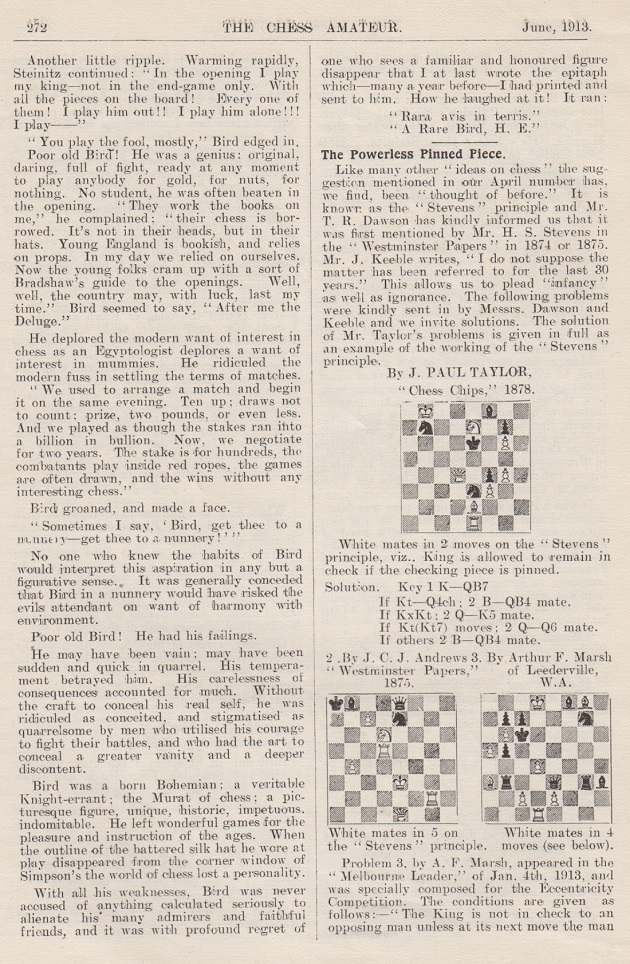

From pages 176-177 of the March 1913 Chess Amateur (see C.N. 7308):

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) asks what grounds Bird had for stating that ‘Blackmar has invented two gambits’ (C.N. 9084). Readers’ suggestions are invited as to the second gambit.

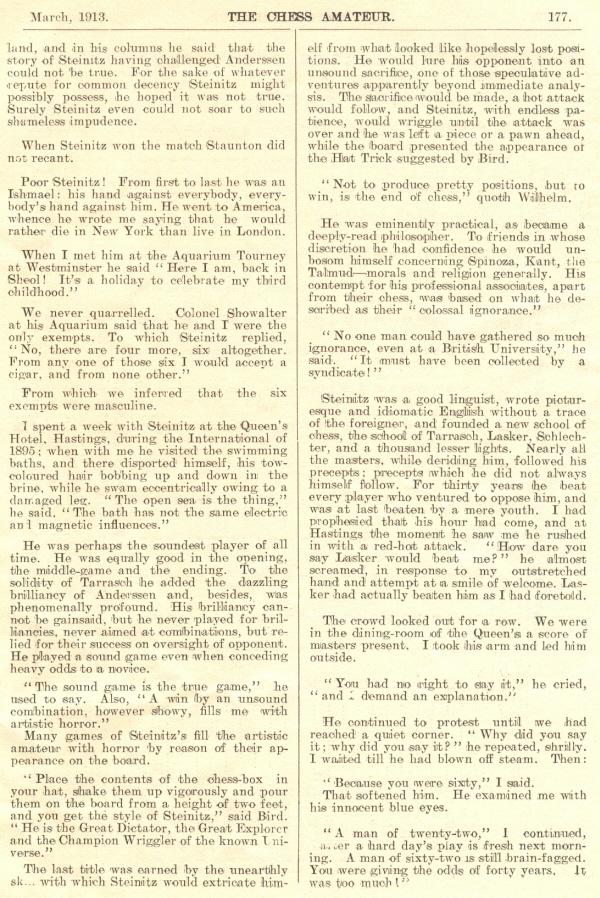

The full article in question is shown below, from the Chess Amateur, June 1913, pages 270-272 (‘Memories of the Masters. H.E. Bird’ by Robert J. Buckley). The Blackmar comment is near the bottom of page 271.

(9299)

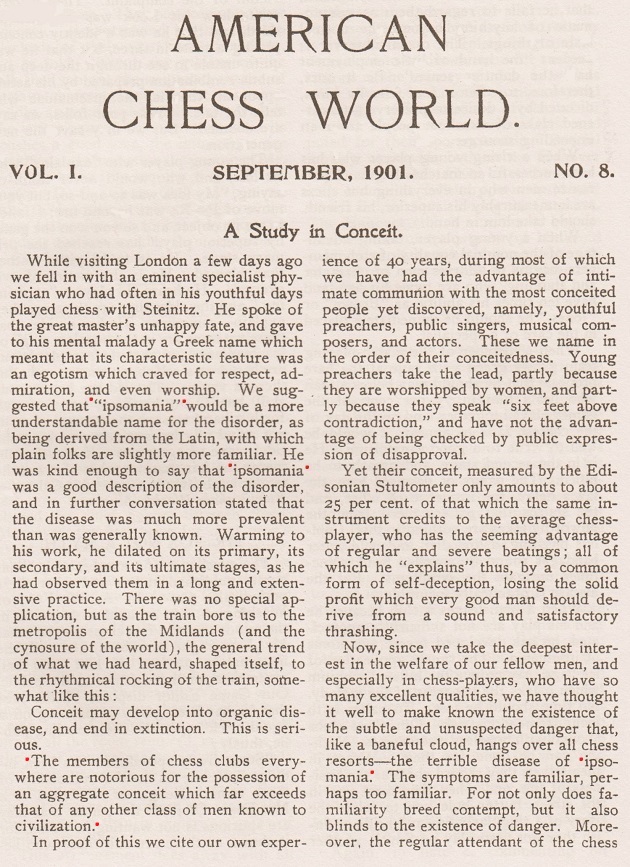

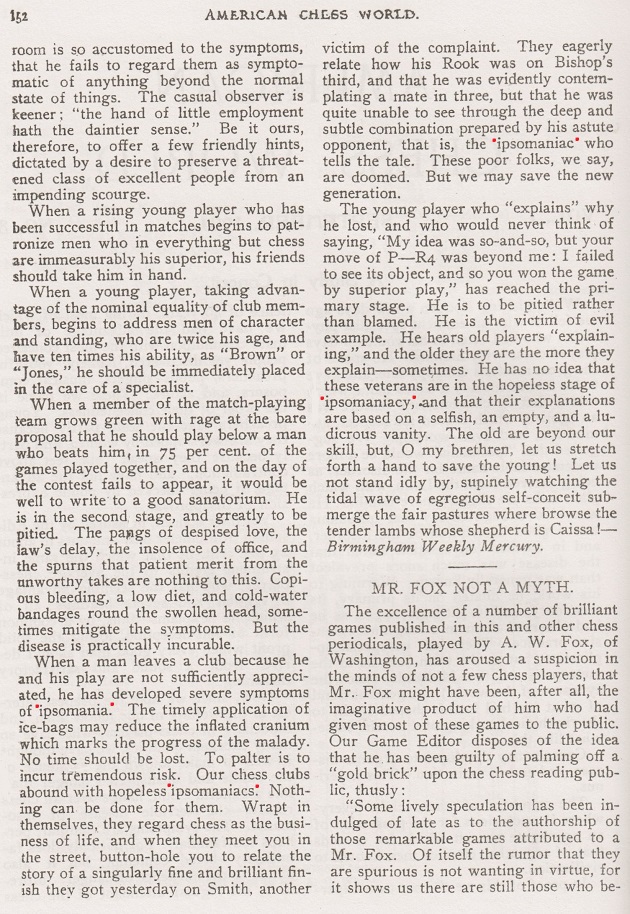

‘The members of chess clubs everywhere are notorious for the possession of an aggregate conceit which far exceeds that of any other class of men known to civilization.’

That remark by Robert John Buckley comes from an article, ‘A Study in Conceit’, in the Birmingham Weekly Mercury which was notable for including the words ipsomania, ipsomaniac and ipsomaniacy. The article was reproduced on pages 151-152 of the September 1901 American Chess World:

An abridged version was published on page 591 of the Literary Digest, 9 November 1901:

Concerning Buckley’s column in the Birmingham Weekly Mercury, see C.N. 11736 (Cleveland Public Library scrapbooks).

Addition on 14 January 2025:

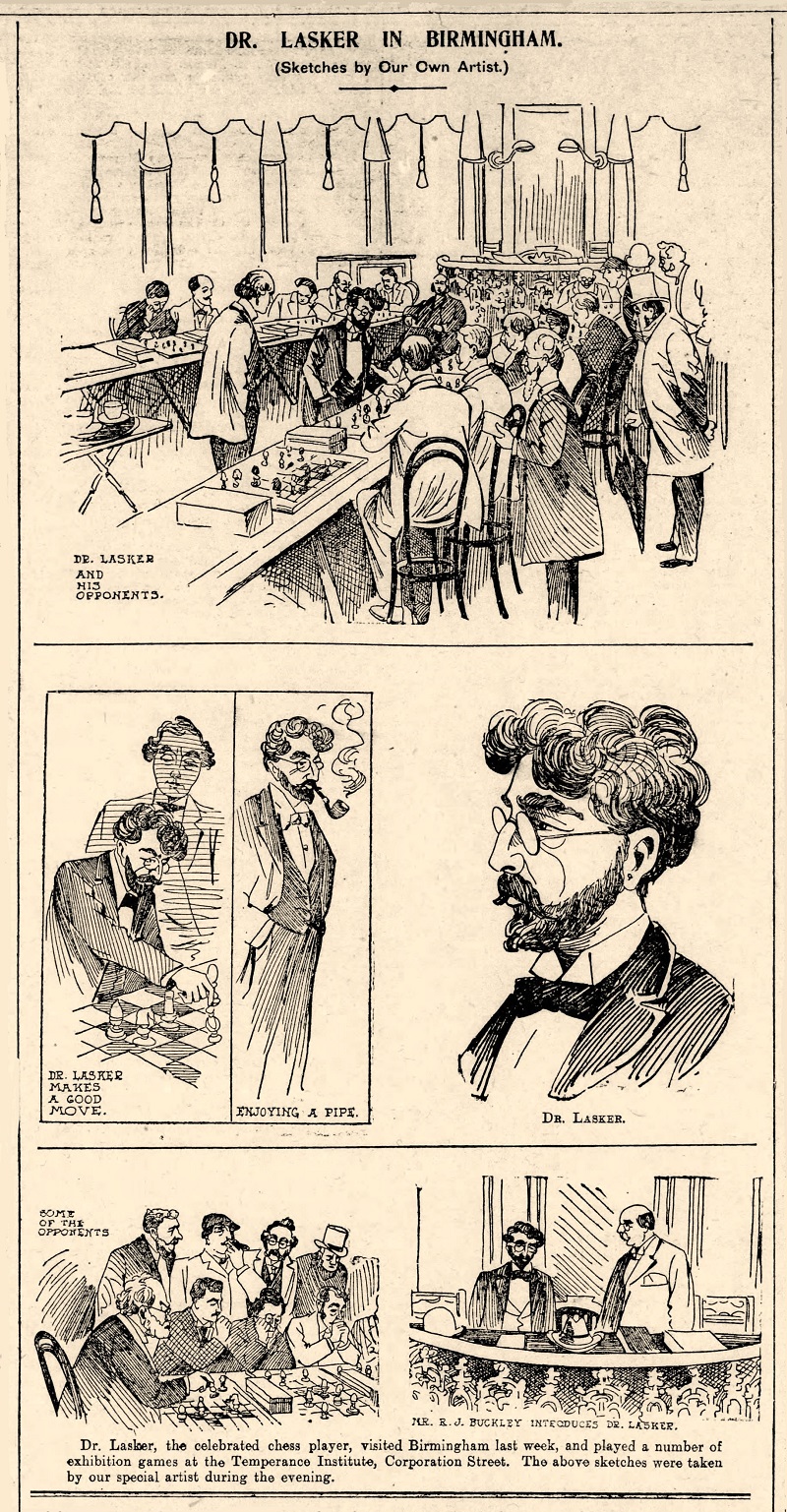

The set of sketches below of Emanuel Lasker with Buckley in Birmingham was published on page 13 of the Birmingham Weekly Post, 1 December 1900:

Latest update: 3 April 2025.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.