Edward Winter

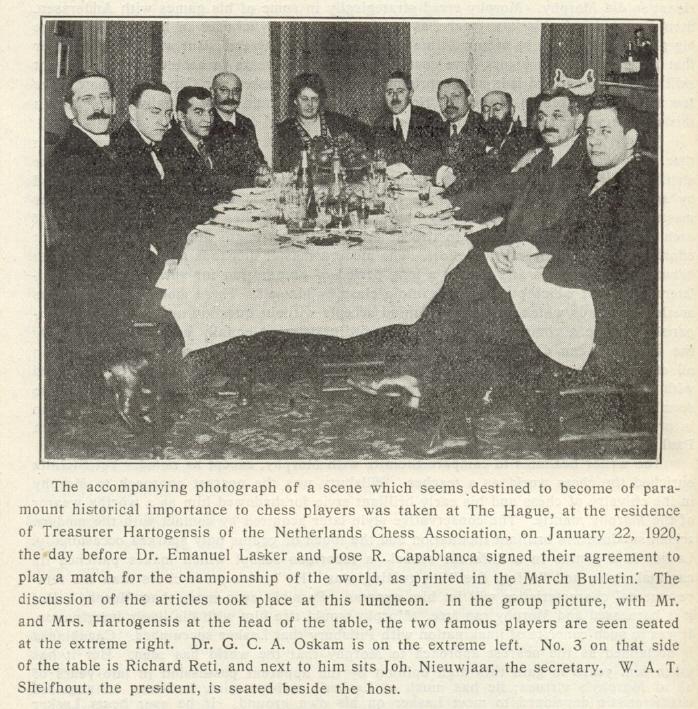

Below is a photograph published on page 88 of the May-June 1920 American Chess Bulletin:

As mentioned in the caption, an agreement for a world championship match between Lasker and Capablanca was signed by the two masters in The Hague on 23 January 1920. It was published on pages 45-46 of the March 1920 American Chess Bulletin, and the final two clauses read:

‘14. Señor Capablanca, for reasons of weight, cannot agree to begin the match before 1 January 1921.

15. In view of Clause 14, Dr Lasker has the right to engage anyone else before 1921 in a match for the world’s championship. Should he lose this contract is void. Should he resign the title it reverts to Señor Capablanca.’

The full document was reprinted on pages 108-109 of our book on Capablanca.

As noted on pages 126-127 of the July-August 1920 American Chess Bulletin, on 27 June newspapers published a cabled report from Amsterdam that Lasker did not intend to play against Capablanca:

‘To say that the chess world is sorely disappointed is putting the case weakly. It was more than disappointed; it was shocked. If Dr Lasker were of a vindictive type which it has not been shown he is, surely no more magnificent revenge for real or fancied grievances could well have been plotted to rebuke an unfeeling world. The text of the message which was flashed under the ocean was as follows:

“From various facts I must infer that the chess world does not like the conditions of our agreement. I cannot play the match, knowing that its rules are widely unpopular. I therefore resign the title of the world’s champion in your favor. You have earned the title, not by the formality of a challenge, but by your brilliant mastery. In your further career I wish you much success.’

Writing to the Telegraaf, Dr Lasker says he would have preferred to lose his title in a keen fight with Capablanca, thus finishing his career logically.”

This was subsequently confirmed by a letter received by Capablanca through Walter Penn Shipley of Philadelphia, who has been named as the temporary referee of the match. Instinctively chessplayers here felt that this was not all there was to the case and in this they were quite right. Naturally, there was more or less surmise as to the real reasons underlying the champion’s decision to take the step, because few believed that the conditions were so “unpopular” but that, with a little concession on both sides, they might readily be whipped into shape to meet the desires of the principals and backers of the match. Not until a month later did any additional explanation reach here from abroad. It appears that Dr Lasker, somewhat discouraged by the unresponsive attitude of the world at large, was unwilling to sacrifice nine months of his life, as he puts it, to a match for which there was a general desire but no really substantial support. Five months, he adds, have elapsed since he and Capablanca signed articles and in all that time received no encouragement outside of the Netherlands. He makes no mention of the offer of $20,000 from Havana, and the presumption is that he had not heard of it at the time he made his abdication in favor of the young Cuban master.

Additional light and, perhaps, not the least important, is shed upon Dr Lasker’s mental condition when, in the course of a brief but highly complimentary reference to Capablanca, he remarks: “He stands above national jealousy.” Concluding, he says: “My feelings are outraged and in such circumstances one cannot be at his best.” This, too, will be regarded as highly significant.

Meanwhile Capablanca had let it be made known that his home town, Havana, was prepared to subscribe the sum of $20,000 if the games of the match were played there, on the strength of which it was not unnatural to suppose that the financial troubles of the players were at an end and that the contest was sure to take place.

Within a fortnight after his return to New York from Cuba, Capablanca took passage on board the steamship Rotterdam, bound for Holland. If it should so transpire that Dr Lasker changes his mind, Capablanca will ignore the fact that the title has been conceded to him. He much prefers to play rather than take the honor by default. Should Dr Lasker persist in his self-effacement, then Capablanca will be ready to meet any worthy challenger under reasonable conditions.’

On page 127 the American Chess Bulletin also quoted from (a) Amos Burn’s column in The Field of 3 July 1920 (Burn welcomed Lasker’s resignation in view of the ‘one-sided conditions he insisted on when called upon to defend his title’ but wondered ‘whether a holder of the world’s championship has the right, upon resigning, to transfer it to any nominee at all’), (b) E.S. Tinsley in the (London) Times of 26 June 1920 (‘Dr Lasker is quite right in thinking the chess world did not like the conditions, but if this unpopularity is a matter of concern to him he would have done more wisely to take it into account before formulating the conditions he insisted on’) and (c) the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle (‘In making a gift of the world’s chess championship to José Capablanca, Emanuel Lasker assumes the exercise of a power which he does not possess’).

The chess press (some sections of which, it may be recalled, had only recently been attempting to strip Lasker of his title – see page 357 of A Chess Omnibus and page 211 of Chess Facts and Fables) was all but unanimous in repudiating Lasker’s abdication in favour of Capablanca. A further example comes from the August 1920 BCM (pages 234-235):

‘What is serious is that he arrogates to himself the right to nominate his successor. This right cannot be allowed by the chess world.

We are of the opinion that, Lasker apart, possibly Lasker included, Señor Capablanca is the strongest of living players. The chess championship, however, cannot be gained on reputation. It must be won by play, and we incline to say by play in a match definitely contested for the title. Lasker having retired without losing a match, the title must be considered temporarily in abeyance.

… There is one distinct compensation in the otherwise unfortunate position which has now arisen with regard to the world’s championship title. This position would not have arisen if there had been in existence the International Chess Federation which was at least on the way to formation when the War broke out.

… Dr Lasker’s abdication and the consequent temporary lapsing of the title of the Chess Champion of the World will be advantageous rather than prejudicial to the cause of chess if they lead to the speedy setting-up of a competent authority, which shall do away with the arbitrary proceedings of the past in connection with the championship.’

The ten-clause agreement between Lasker and Capablanca, dated 10 August, was published on page 283 of the September 1920 BCM, after Lasker had given it in his Telegraaf column. The final clause read:

‘10. I, Dr Em. Lasker, maintain my position with regards to the title. Señor Capablanca is champion of the world. Nevertheless, if the chess friends of Havana confirm their offer, I shall play my last match for the championship of the world under the above conditions.’

After Lasker’s name at the end of the text came Capablanca’s, with the statement, ‘I agree to the above conditions’.

As quoted on page 346 of the September 1920 Chess Amateur, the Morning Post noted Lasker’s insistence that Capablanca would be defending his title and commented: ‘Lasker, therefore, cannot lose the championship but may win it – an ingenious quibble that is not likely to trouble Capablanca, whose sole object is to play the match.’

On page 141 of the September-October 1920 American Chess Bulletin the following text was published under the heading ‘Dr Lasker and the Championship’:

‘That Dr Emanuel Lasker is firm in his determination to regard José R. Capablanca, in whose favor he retired some time ago, as the present world’s champion and that, even should he win the match at Havana in January next, he will not retain the title thus recovered but hand it back for competition among the younger masters, is evident from a letter written by him to the publisher of the American Chess Bulletin. It will be his last match for the championship, but he throws no light on the question whether he will again be seen in tournament play. He also believes that an international chess federation is most necessary and that America should take the lead. Dr Lasker writes:

“I shall no more be champion. Should I win the title in the contest at Havana, it will be only to surrender it to the competition of the young masters.

It is a pity that the chess world is not organized. That 20 people pull in 20 different directions does no good. Let those who have the cause of chess at heart find themselves and work together.

My own idea is that Mr Shipley, whom we all know as a just and lovable man, should start the ball rolling. In approaching Argentine and Cuba, he would be able to form an American Chess Federation that would be willing and strong to support international chess. Europe is hopelessly torn into fractions, but several associations in Europe that are desirous to see international chess prosper would gladly gravitate toward an active American Chess Federation.”’

The next page contained a statement by Capablanca (the full text of which is given on page 111 of our book on him):

‘In case the match with Dr Lasker is played and I remain the champion, I shall insist in all future championship matches that there be only one session of play a day of either five or six hours, preferably six.

… As the champion of the world, I shall insist in introducing modifications in the playing rules of matches and tournaments that will tend to make them more attractive to its supporters, at the same time always safeguarding the interests of the real masters.

In whatever modification I may introduce in the championship rules I shall look for no personal advantage either of a psychological character or otherwise, but will always be guided by three things, viz: 1, the interests of the chess masters; 2, the interest of the chess public, and 3, last but not least, the interest of chess, which to me, far more than a game, is an art.

The Hague, 20 August 1920

J.R. Capablanca

Chess Champion of the World.’

Certain details regarding the anticipated match remained to be negotiated, and the American Chess Bulletin (November 1920, page 172) reported:

‘José R. Capablanca, who now claims the championship of the world by virtue of the resignation of Dr Emanuel Lasker, and in accordance with the conditions of their first contract, but with whom, nevertheless, he expects to play a match for the title in Havana during January and February next, returned to New York from England 12 November, on board the steamship Adriatic of the White Star Line. The young Cuban master had made a special trip to Europe for the purpose of inducing Dr Lasker to play the match, and in this he was successful, so far as obtaining his consent was concerned, but, on the other hand, the latter made conditions of a financial nature that were not mentioned in the bond. In other words, the famous player, who is now the ex-champion, according to both himself and Capablanca, demands an advance payment of his share of the purse of $20,000, before he leaves Europe, and another payment before he starts to play the match in Havana. Capablanca stated that Señor R. Truffin, President of one of the biggest Cuban sugar corporations, had personally written to Dr Lasker, confirming the offer of the purse. The young master, therefore, was quite confident in the hope that the match will start as scheduled.’

Just before the end of the year Lasker announced that he would indeed play. From page 2 of the January 1921 American Chess Bulletin:

‘The following message from Señor Truffin, President of the Union Club, was despatched to Dr Lasker on 24 December:

“Will wire $3,000 provided you cable back you will come, giving date for match to begin. Weather here fine till end of April. Capablanca already here. Our answer delayed due to absence of principal contributors.”

A laconic reply came back from Dr Lasker on 28 December, which read: “Begin 10 March”.’

The same page of the Bulletin named the four parties each contributing $5,000 to the purse: Hon. Mario G. Menocal (President of Cuba), Señor Regino Truffin (President of the Union Club), Señor Aníbal Mesa (‘who is reputed to have reaped an immense fortune from the sugar business last year’), and the Marianao Casino.

Lasker’s financial demands occasioned much negative reaction. One loose end at present concerns the affirmation on page 182 of the August 1920 issue of La Stratégie that he was insisting that the match would not be for the world championship unless more money (i.e. beyond the $20,000 from Havana) was provided. Perhaps a Dutch reader with access to Lasker’s Telegraaf column can clarify this point. It may or may not be relevant that the final ‘rules and regulations’ for the match, which were agreed upon shortly after Lasker’s arrival in Havana and were published on page 39 of Capablanca’s match book contained no reference to the world championship. Moreover, although the financial conditions were reiterated there (‘The $20,000 purse to be divided as follows: Dr Lasker to receive $11,000, Capablanca $9,000 win or lose or draw’), the following addition was recorded:

‘After five games had been played, the “Commission for the encouragement of touring throughout Cuba” gave an extra prize of $5,000, of which $3,000 should go to the winner of the match and $2,000 to the loser.’

Following his arrival in Cuba (which was delayed until 7 March, with the result that the match did not start until 15 March) Lasker showed no inclination to withdraw his abdication. Page 46 of the March 1921 American Chess Bulletin reported:

‘According to a long interview printed in the Havana newspaper El Mundo, Dr Lasker, who has not been defeated for the championship since he acquired the title from William Steinitz on 26 May 1894, at Montreal, insists that his cession of the title to Capablanca at The Hague in June of last year, without playing, holds good and that he himself occupies the role of challenger, instead of his youthful rival. It follows that, unless Dr Lasker should win the match, title to the championship will rest with Capablanca, at least so far as the ex-champion is concerned.’

Although Lasker was later to maintain this standpoint in, in particular, his book Mein Wettkampf mit Capablanca (Berlin and Leipzig, 1922), the chess world took scant notice. Thus page 97 of the May-June 1921 American Chess Bulletin had a feature entitled ‘José Raúl Capablanca, the Champion’ which contained such references as ‘the defeated champion had not won a single game’ and ‘Hail to Caissa’s new lord and master: José Raúl Capablanca’.

In his Introduction to Capablanca’s match book Hartwig Cassel, who spent nine weeks in Havana, referred briefly (on page 6) to Lasker’s resignation in 1920 but wrote on page 8:

‘On Wednesday evening, 27 April, in the small reception room of the Union Club, the principals, referee and seconds met and, after a brief discussion, declared the match officially at an end. It was then that Capablanca was declared to be the winner and the new world’s champion.’

The Cuban gave his own views of the abdication issue in an article on pages 376-380 of the October 1922 BCM when answering a range of points made by Lasker in Mein Wettkampf mit Capablanca:

‘I obtained from Havana a much better offer than I had been tendered anywhere else, and just as I was on the point of communicating with Dr Lasker about it, the cable brought the news that Dr Lasker had resigned the championship, which, according to one of the clauses of our agreement, made me the world’s champion. This same clause existed in the agreement entered into in 1913 between Dr Lasker and Rubinstein for a match for the world’s championship. There is no other fair way to arrange this matter; if the champion accepts a challenge and afterwards does not play, although his challenger has meanwhile stood by the letter of the agreement, the title of champion must go to the challenger. Any other arrangement would be most unfair to the challenger. Nevertheless, I preferred to play rather than to come to championship honours without actually winning them over the board. To that effect I made a second journey to Holland (this time all the way from Cuba) to put the matter before Dr Lasker, to whom, meanwhile, I had written about Havana’s offer, and asked him at the same time to meet me at The Hague. There, in August, a second agreement was reached …’

This account gave the impression that Lasker withdrew his abdication, but such was not the case. It may noted here that the 26 August 1913 agreement for a Lasker v Rubinstein match was published on pages 220-221 of the October 1913 American Chess Bulletin and that the final point stated:

‘The two masters, by word of honor, take the obligation on themselves of playing the match, except [if] they are prevented by force majeure. Rubinstein furthermore acknowledges his obligation, not only if he should win the match but also if for other reasons Dr Lasker should choose to resign the title in favor of his opponent, to hold on to the traditions created by Steinitz.’

The confusion and controversy in 1920-21 are well illustrated by the German chess press. After the news broke of Lasker’s resignation, the July 1920 Deutsche Schachzeitung (page 145) had the headline, ‘Capablanca, der neue Schachweltmeister’. Page 161 of the 22 August 1920 issue of Deutsches Wochenschach responded with the headline ‘Capablanca – nicht Weltmeister’. When the August-September 1920 Deutsche Schachzeitung discussed the provision in the August 1920 agreement that Capablanca was already champion, a footnote on page 199 remarked that this was a view against which the entire chess world was rebelling (‘Eine Ansicht, gegen die sich die gesamte Schachwelt auflehnt’). Despite having entitled an article ‘Capablanca the new world chess champion’ in June 1920, the Deutsche Schachzeitung came out with the identical sentiments (including the word ‘new’) in a heading on page 112 of its May 1921 issue, following the conclusion of the Havana match.

After citing such a welter of statements, opinions, claims and counter-claims about rules, money and politics, we venture no more than a summary of the key points:

i) The January 1920 draft agreement signed by Lasker and Capablanca stipulated that if Lasker resigned his title the Cuban would become world champion.

ii) Lasker announced his abdication in June 1920, at which time no specific venue or dates for a match with Capablanca had been established.

iii) Since Capablanca wished to become world champion by defeating Lasker over the board, he reacted to Lasker’s statement by going to the Netherlands to negotiate with him, in August 1920. During those discussions (and afterwards) Lasker maintained that he was no longer the world champion, and in the text of the two masters’ agreement to play a match in Havana Capablanca accepted Lasker’s abdication in his favour. Ten days later Capablanca again declared his acceptance of the world championship title.

iv) Nevertheless, when the match ended, in April 1921, Capablanca was officially declared in Havana ‘the new world’s champion’.

v) The press was dismissive of Lasker’s wish to confer the title on Capablanca, even questioning the legality of such an initiative, and in 1921 it regarded the Cuban as having become world champion by dint of defeating Lasker over the board.

The above text first appeared in C.N. 3346.

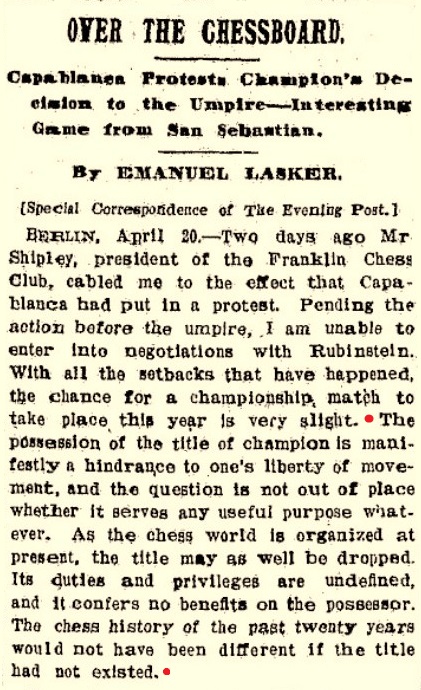

Comments by Lasker on the world championship title’s lack of value were quoted in C.N. 2060, from page 11 of the New York Evening Post of 4 May 1912 (see below), reprinted on page 123 of the June 1912 American Chess Bulletin:

‘The possession of the title of champion is manifestly a hindrance to one’s liberty of movement, and the question is not out of place whether it serves any useful purpose whatever. As the chess world is organized at present, the title may as well be dropped. Its duties and privileges are undefined, and it confers no benefits on the possessor. The chess history of the past 20 years would not have been different if the title had not existed.’

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.