Edward Winter

Below is our translation of an article by J.R. Capablanca published on pages 1-4 of the Uruguayan chess magazine Mundial, May 1927.

In each generation there are a few masters who concentrate the attention of chess aficionados and critics. This attention is particularly intensified for the person holding the world crown. Comments are varied and take on different forms. The majority of aficionados take note only of results and base their opinion solely, or almost solely, on the success or otherwise of the champion. However, a few experts, made up mainly of the other masters, go into the question in greater depth, and their opinions are influenced by numerous factors other than “winning or losing”. Although there are many aspects worthy of being considered, the experts’ opinions are generally based on the three following: Depth, Combinative Power and Style. By ’’Depth’’ is meant the level of aptitude for considering possibilities in difficult positions; in other words, positional judgment.

By “Combinative Power” is meant the aptitude for seeing clearly through to the end of a combination, taking advantage of some already-existing chance, or preparing the combination.

And by “Style” is meant the general system of play, whether it be simple or complicated, slow and solid or brilliant and enterprising.

If chess is considered an exact science it is obvious that there must exist only one correct way of playing, whatever that is, and it solely remains to find it. If it is considered an art, then there must be various ways, and the choice is completely dependent upon the individual characteristics of the player. He will naturally favour the kind of play in which his talent is most at home.

The great majority of the chess public, as well as a smaller majority of experts, look at style when selecting their preference for the champion of one generation rather than all the other champions. Beginning with Labourdonnais and going up to the present incumbent, and including Lasker, we find that clearly the greatest stylist was Morphy. This is the reason, though it may not be the only one, why he is generally acclaimed as the greatest of all. Labourdonnais appears to have had success in complicated positions involving direct attacks on the king where superficiality was not excluded. He always sought this kind of play and practically never played anything else. His style, therefore, lacked clarity and, often, energy.

Anderssen, a born chessplayer, chiefly played combinative games. One or two of them are considered the most beautiful products of all time. But, like his predecessor Labourdonnais, he was a victim of the general concept of the period, according to which chess should be played only in that way. As a result, his play and style lacked coherence and, we may say, scope.

Steinitz was a better stylist at the beginning of his career than in his final period. He began as a brilliant player of open games and finished as a prototype of the extremely closed style. At some point he must have passed, however fleetingly, through the stage representing a happy medium, the perfect type of play.

He was the first person to establish the basic principles of the real general strategy of the game. He was also a pioneer as well as one of the most profound investigators of the hidden truths of chess. At a certain time he played the openings well, but later he converted his principles into caprices, thereby lessening his winning chances in serious battles against some of his most formidable opponents. His combinative power was very great. He was also a very fine endgame player, and it is in fact essential to be a strong endgame player to become world champion. He was very tenacious and in his youth, when he was playing at the top of his form, he was almost invincible.

Lasker, natural genius developed by very hard work in the early part of his career, never adopted a type of play that could be classified as a defined style. So much so, in fact, that this has moved some masters to declare that Lasker is absolutely lacking in style. The truth is that if his style had to be classified, it could only be termed “indefinite”. It has been said that he is an individualist, that he plays more against the player and his defects than against the position of the pieces. This is true to a certain extent with regard to many players, and there is perhaps a great part of truth to it in the case of Lasker, but I do not think that such things can be stated absolutely. In recent years, when I have had the opportunity to observe him in some of his games, it has seemed to me that he was often changing tactics, even against the same player. The defect of his style is that his play generally seems abnormal. One of the greatest players during the period when Lasker was champion has said that there was something mysterious in his play which he could not understand. On the other hand, Lasker has great qualities. He is very tenacious. He can defend bad positions admirably well. In this sense he had so much success during his long career as champion that finally it was transformed into a defect which sometimes led him to think that he could defend positions which really could not have been sustained against correct play. He could carry an attack through to the end in a way that very few other players could match.

In endings for a long time he maintained the reputation of having no equals. If he reached an ending in which he had a winning advantage, however small, it was almost a certainty that he would win the game. Very few victories escaped him in endings. On the other hand, if he had the worse of it, his opponent could not permit himself the liberty of conceding him the slightest chance. His combinative power in the middle game is also very great.

Morphy was a great stylist. In the opening he aimed to develop all his pieces rapidly. Developing them and quickly bringing them into action was his idea. In this sense, from the point of view of style, he was completely correct. In his time the question of Position was not properly understood, except by himself. This brought him enormous advantages, and he deserves nothing but praise. It could be said of him that he was the forerunner of developments in this extremely important part of the game. He made a special study of the openings, with such success that in many games his opponents had an inferior position after six moves. This is also praiseworthy since in those days he had little to guide him. Players of the time thought that violent attacks against the king and other combinations of this kind were the only things worthy of consideration. It may be said that they began by making combinations from the first move, without paying sufficient attention to the question of development, about which Morphy was extremely careful. His games show that he had an outstanding playing style. It was simple and direct, without affectation; he did not seek complications but nor did he avoid them, which is the real way to play. He was a good endgame player and proved himself a clever defender of difficult positions. His combinative power was wholly sufficient for what he undertook, but it was not, as most players of today think, the most important aspect of his talent. That was his style, which, as far as could be judged, was perfect.

It is often said that Morphy is the strongest player there has ever been. In our judgment such assertions are absurd, since not only do they lack any basis but it is in any case impossible to prove them. All that would be possible is to make comparisons on the basis of his matches, and according to the strength of his opponents. If we made such comparisons, the result would be disastrous for the assertions of the admirers of the great master of the past.

But Morphy was not only doubtless the strongest player of his period; he was also a creator in chess and the prototype of what could be called the perfect style. Regarding the results of his battles, there are various points to consider. There is one, above all, that is hardly known at all. We refer to the fact that the great American master never played isolated games for amusement; every time he played, he put all his knowledge into the game. In other words, for him any game he played immediately assumed, so to term it, the proportions of a match game. We do not believe that any other player has done this. Consequently, he should be judged only on his great matches, especially those against Anderssen and Harrwitz. Simply playing through the games of those two matches will show that they hardly contain any so-called brilliant combinations.

Contrary to the general belief, which is the result of ignorance, Morphy’s main strength was not his combinative power but his positional play and his general style. The truth is that combinations can be made only when the position permits it. The majority of the games in these two matches were won by Morphy in direct and simple fashion and it is this simple and logical procedure which is the basis of true beauty in chess, from the point of view of the great masters.

Concerning an oft-repeated declaration by a large number of admirers, who believe that Morphy would beat all today’s players, as we have already said, this has no foundation. On the other hand, if Morphy were resurrected and were to play immediately only with the knowledge of his time, he would most certainly be defeated by many present-day masters. Nevertheless, it is logical to suppose that he would soon be at the necessary level to compete against the best, but there is no way of knowing exactly how successful he would be.

There is no doubt that the science of chess has greatly developed in the past 60 years. Players offer more resistance every day and the requirements and conditions necessary to overcome other masters are greater than before. In short, the ideal way of playing a game would be: rapid development of the pieces to points of strategic use for attack or defence, taking into account the fact that the two main elements are Time and Position.

Calm in defence and decisiveness in attack. Not exaggerated attention to the possibility of obtaining any material advantage, since often therein lies victory. Not seeking complications except in extreme cases, but not refusing them either. Finally, in a word, being ready to compete in any kind or phase of play, whether it be the opening, ending or anything else; the game may be complicated or simple, but it is the latter path which is to be preferred within the limits permitted by the two principal elements, Time and Position.’

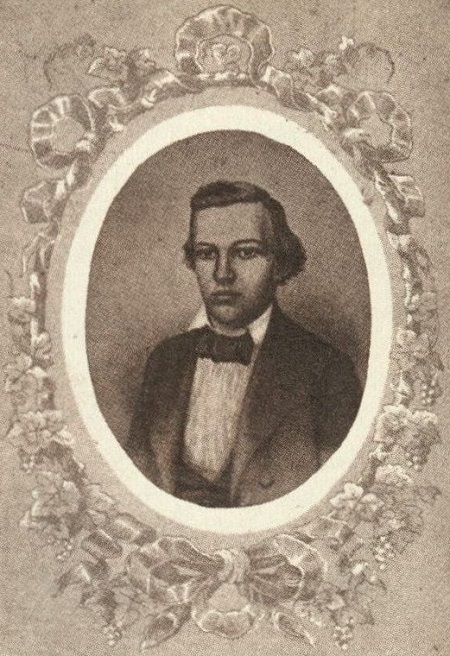

Paul Morphy (Chessworld, January-February 1964, page 53)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.