Edward Winter

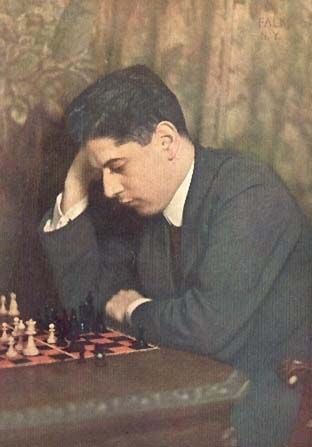

José Raúl Capablanca (see C.N.s 3442 and 3447)

Below is our translation of an article by Capablanca published on pages 3-5 of Capablanca-Magazine, 25 April 1912:

‘At the outset of this critical assessment, I must point out that players’ weaknesses, like their strengths, are relative within the circle in which they belong, for the weakness of one player compared with other entrants in the tournament would no longer be a weakness in the context of players slightly less strong. In chess, as in life, everything is relative.

Rubinstein, who, at the chess board, is the glory of Russia, was born in Łódź in 1882 [sic], and is thus 30 years old. He is extremely astute and a profound student of the game; it is related that he studies for two or three hours every morning; he is a great admirer of Morphy, whose games he probably knows by heart. He is very observant and when, in San Sebastián in 1911, I was amusing myself playing fast games against Dr Bernstein, his compatriot, he always came to watch the contest, often making the observation that I possessed tactical ability superior to anyone else’s. This is clear proof of the great Russian expert’s modesty.

Rubinstein has made a special study of the queen’s pawn opening, and his opponents can be entirely sure that as White he will open with 1 d4. There have been occasions when he has varied, but these have been rare. With Black he almost always plays the French Defence against 1 e4 and he has made a special study of this opening too.

His openings are irreproachable because he plays only what he has studied in the greatest depth. His middle-game play is worthy of the great master that he is, while it is generally agreed that he is extraordinarily strong in the endgame. From this it may be deduced that the Russian master is very difficult to defeat. To beat him it is necessary to proceed step by step and with great care because he is forever preparing traps for his opponent.

His main successes have been Carlsbad, 1907, first prize; Ostend, 1907, first and second prizes equal with Bernstein; St Petersburg, 1909, first and second prizes equal with Lasker, the world champion, whom he beat in their individual game; San Sebastián, 1911, second and third prizes equal with Vidmar, and finally San Sebastián, 1912 first prize.

Rubinstein has never been lower than third in an international tournament, which is a record matched by no other player except Lasker. Today Rubinstein is, in my opinion, the strongest European player, leaving aside Lasker, who, as world champion, has the right to be considered the first.

Spielmann and Nimzowitsch, who tied for second and third prizes, are today the best two exponents of the brilliance of the old school, under the theory of the modern school. In other words, whilst recognizing the solid points of the modern school, they attack with the determination and brilliance which characterized the old players. Their play is similar in some respects. Both play things which other masters leave to one side, and the continuations they choose, although very brilliant, are not the result of the depth of knowledge which enables them to see certain victory, but are due to the influence of what is called “positional judgment”. That is to say, they do not see a combination through to the end and cannot be certain what is going to happen; but they believe it is good and that the position they will obtain will give them an attack which ought to win one way or another, and they thus embark upon that line, even sacrificing pieces to carry out their plans. It sometimes happens that they were wrong and that they lose; but sometimes also, despite the fact that they have been wrong, the resulting position is so difficult that the opponent does not see the correct course, misses his way and loses.

Despite these similarities, their styles are different in important respects. Spielmann is a purely attacking player. Nimzowitsch is a great positional player and his middle-game tactical skill is, in my view, superior to that of any other competitor at San Sebastián. Spielmann is better in the endgame since the Russian expert, for some reason that I cannot explain, is weak in this phase of the game and he sometimes loses a difficult endgame without any reason.

Tarrasch, the hero of a great number of tournaments, is at 51 years of age the oldest player in the tournament. Back in 1889 it happened that while Tarrasch, then the strongest player in Germany, was obtaining first prize in a major tournament, Dr Lasker was winning first prize in a minor tournament and obtaining the title of Master. At that time everyone’s look was concentrated on Tarrasch, since it was expected that he would be the one to fight against the elderly Steinitz for his world championship title, and nobody could imagine that the young Lasker, then only 20, would be the one to achieve what the then famous Tarrasch would never do: dispute a match with the mighty Wilhelm Steinitz. Lasker beat Steinitz 10-5 in 1894 in a memorable match, and it was only four years ago that, after strong arguments in print, Dr Tarrasch faced his rival Dr Lasker in a match. At the time Tarrasch had an enormous reputation. He had won eight first prizes in international tournaments, three of them consecutively with the loss of just one game. His views on opening moves, etc. were almost infallible for Germans, who were on his side and wanted him to win; Lasker was German by birth and world champion, but they disapproved of his living in the United States. The result of the match was a disaster for Tarrasch and his supporters; Lasker beat him by eight games to three with five draws. The chess world wrote Tarrasch off – “a hope which has passed”, and even believed that he had never been as strong as he claimed, and that now that this had been discovered he could no longer excel in tournaments. But this has not been so; in the two San Sebastián tournaments in 1911 and 1912 his play showed that he is still a player to be feared and that beating him is a Herculean task. In 1911 he was equal 5-7th with Nimzowitsch and Schlechter, and this year 4th, ahead of Marshall, Schlechter, etc. In first-class tournaments this indicates a very great latent strength.

Dr Tarrasch has studied, and continues to study, the game a great deal, and modern theory has advanced under his impetus. He sometimes plays the first 15 moves of a game at lightning speed, which, in a player as calm and deliberate as him, is clear proof that everything has been studied and prepared. Against me at San Sebastián in 1911 he made his first 16 moves in three minutes. His style is characterized by solidity; he tries to construct a wall of steel and leave his opponent to crash into it. He will take great pains to obtain or maintain a pawn, and this often costs him the game. Finally, though this does not concern chess but rather the personal character of the chessplayer, Dr Tarrasch is a great admirer of music and of the fair sex.’

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.