Edward Winter

The late Olga Capablanca Clark wrote an article entitled ‘The Young Manhood of José Raoul Capablanca’ on pages 20-37 of the third and final issue of Chessworld (May-June 1964). Exceptionally well illustrated, the piece was ‘based on conversations she had with her husband regarding his feeling toward chess and toward the approach of the [1911] San Sebastián tournament specifically’. Another article, published on pages 114-139 of Town and Country, February 1945, dealt mainly with Nottingham, 1936. She also wrote the Preface to Capablanca’s Chess Lectures (New York, 1966 and London, 1967), and her writings were included in José Raoul Capablanca Ein Schachmythos (Düsseldorf, 1989).

In the 1980s and early 1990s the two of us exchanged many dozens of letters and telephone calls, and she contributed four articles to Chess Notes. The first, also reproduced by many other magazines, was an account of an offhand game between Capablanca and Tartakower, Capa’s score-sheet of which she was prepared to sell for a minimum of $10,000. No bids were received. The second and third articles also contained reminiscences from Paris in the late 1930s, and the fourth concerned their wedding day, in 1938. Our intention was to work together on a volume of her memoirs, but the project regretfully had to be abandoned with only 20 or 30 pages written. Below are some gleanings from hitherto unpublished material which offers a unique insight into Capablanca’s personality and lifestyle.

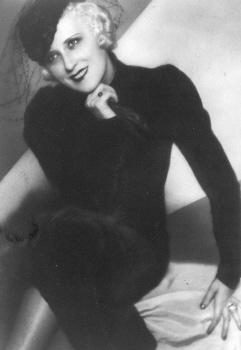

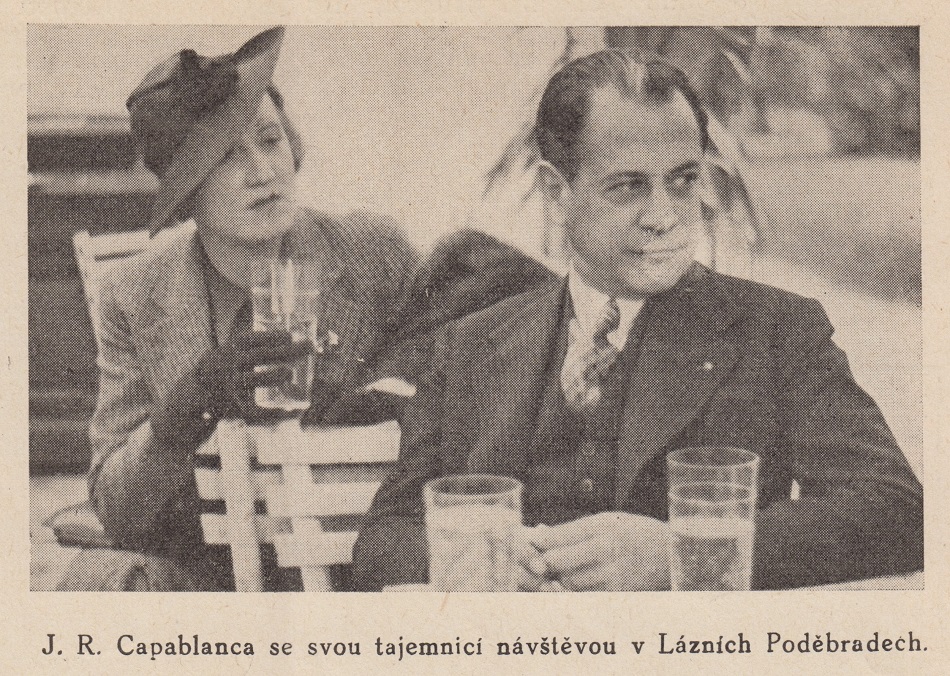

He had married Gloria Simoni Betancourt in 1921, eight months after becoming world champion. The couple had two children, but the marriage proved unsuccessful. In the late spring of 1934 Capablanca met Olga Chagodaef (née Choubaroff), a Russian princess, at an impromptu party given by a close friend of hers, Myrtle H., in the latter’s mansion on Riverside Drive, New York.

Olga Capablanca recalled: ‘Everyone got up to dance except a man who, I had vaguely noticed, sought to be near me. Quietly but distinctly he said, “Some day you and I will be married”.’

As she was about to go home, the man said to her, ‘Please give me your telephone number. Permit me to call you. My name is Capablanca.’

The following morning her telephone rang:

‘It was Capablanca. “I hope you remember you are to have dinner with me tonight.” Whether I did, or did not, didn’t matter. He firmly said he would call for me at six. Precisely at six the porter rang from downstairs. When I came down Capablanca stood by his car. As he took off his hat I was surprised to see how handsome he was. From that time on, he called me every other day, and if I could not see him because of some other engagements he would be awfully unhappy. Sometimes he would spend most of the night on the bench opposite our windows on Central Park waiting for my return. If I said to him some cross words, as happened a few times, tears welled in his eyes, which would make me miserably guilty.

… Now I called him Capa and smilingly listened to his threats to knock out of me every bit of glamour. A few weeks later he received an invitation [to give two simultaneous displays in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in October 1934]. Before leaving he did something completely unlike his secretive nature. To the press people, gathered round him as usual, he made an extraordinary statement: “You have always prodded me with questions about my private life. Now I will give you some news of importance. You can print it anywhere you wish: for the first time in his life Capablanca is in love.” This was told me by the Cuban Consul – Pablo Suárez I believe was his name. I was surprised and somewhat embarrassed, but my thoughts were no more confused. I already shared Capablanca’s feelings.

When he returned to New York and kissed me, I told him so. “This is our fate”, said Capa. “I knew it from the very beginning. I shall regain my crown for you. There were years when life had been rather meaningless to me, but now I shall return to my own. I shall prove again that I am the best chess player in the world”.’

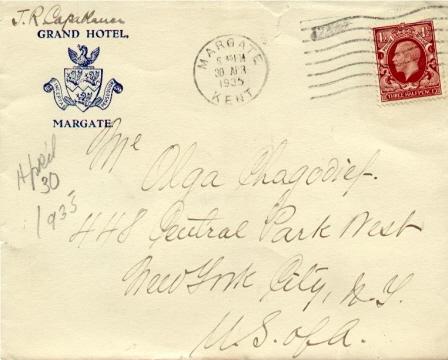

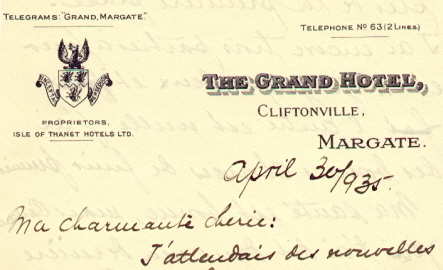

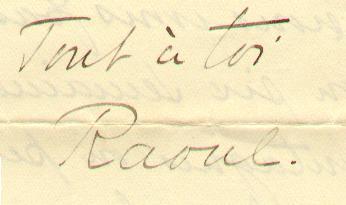

It is notable that he signed the letter ‘Raoul’:

Olga Capablanca’s reminiscences included much about Europe in the mid- and late 1930s. In the Moscow tournament of 1935 or 1936, she said, Capablanca was friendly with Nikolai Krylenko. At that event the Soviets helped each other, and the Cuban complained to Stalin, who came to the event and watched from behind a curtain.

The following relates to circa 1936:

‘It was my first trip to Belgium. Soon after our arrival Capa had to present his diplomatic credentials, as was required in the service. His title was that of Commercial Counsel, although his famous name had carried him far above the official appointment. When Capa, in the company of our Minister, had arrived at the Palace, the King of Belgium [Leopold III] was in the midst of some impressive audience. As the major-domo announced the names of the two Cuban diplomats, the King stopped in the middle of the reception at the other end of the immense palatial hall. “Capablanca!”, he loudly repeated, then, waving aside protocol exigencies, like an awe-stricken boy he ran across the hall to meet the newcomers. “Oh, maestro”, he said, grasping Capa’s hand. “All my life I have wanted to meet you. I have studied your games – and now you are here in person!” This was told to me by the Minister. Capa, of course, said nothing.

He was most secretive and proud and preferred to be left alone, although when necessary, as his position as a diplomat required, he would be most charming and interesting. The fastidious London newspapers described him as the best dressed and most handsome among his peers. He, however, was totally uninterested in the publicity that accompanied him everywhere he went. In his discarded mail I found invitations from Maharajahs, letters from the House of Marlborough and from several celebrities of the time. He remained a very private man, always polite, attentive, but evasive within the realms of possibility for a world famous man. His was a typical high-class European attitude, shunning publicity. Very often he would not even buy the newspaper with some nice article about him. When I remarked about it he shrugged his shoulders. “If I gathered up and kept all the newspapers that were kind enough to give me some of their space I would have to buy a house to store them.” Later I found that he had kept every little note I had written. For me he had different rules – this he proclaimed several times. Perhaps the nicest thing he said to me was, “You are the only person who doesn’t interfere with my being alone”. With a special man like Capa one had to know when to be silent, perhaps for days. Then, if his mood changed, all one had to do was to find themes that would interest him. To see that special green light in his eyes, a rare unusual light that would indicate his interest and attention, was the most rewarding feeling I knew.’

Two further episodes, both from the 1930s, are related below. The first concerns the couple’s opportunity to meet the Duke and Duchess of Windsor:

‘Capa and I were in Paris when, shortly after [Edward VIII’s abdication], the news was announced about their arrival from, I believe, a Rothschild estate in Austria. Parisians were agog with curiosity and enthusiasm; after all, it wasn’t their king. The attitude in London was quite different through all this ticklish situation. I could tell some sharp-edged stories since quite a few of our British friends belonged to the entourage.

In Paris the American Ambassador Bullitt had decided to give a great ball. Practically everybody who was a somebody was invited. The gilt-edged invitation said “Ten o’clock”.

Capa, as ever meticulously precise, got me ready on time. As we arrived at the Embassy the bells of some ancient church nearby melodiously announced the hour. We entered through the side door while the butlers were still hurriedly adjusting some flower vases.

Two more people arrived about this time through the same entrance: a highly-decorated French General and then, shortly afterwards, a pleasant-looking elderly lady in a black lace dress and several rows of large pearls. These aroused in me a certain admiration: the courage to wear so prominently such obviously false pearls at this event. I liked her untouched silvery white hair; she too felt friendlily disposed and soon we found some common friends in New York. Capa and the old General became engrossed in each other, discussing the Napoleonic wars.

Meanwhile, elegant crowds started pouring in. I quickly noticed some extra attentions bestowed on my lady with the pearls. And before long I knew these pearls were real. And she was Mrs McL., of great wealth and much decorated by the French Government.

Quite soon the Chancellor, Mr Robert Murphy, tall, blond and somewhat breathless, came over for us.

“Mr and Madame Capablanca, please join me to meet the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. They have just arrived, and the Ambassador is with them.”

I touched Capa’s sleeve, repeating first in French, then in English, reserved for our official communications.

“Dear, please come to meet the Duke and Duchess of Windsor.”

No response. In vain I insisted. Capa only made a slight gesture towards Murphy, who was our good friend, then sharply turned back to the General. One could hear, “Vagram … the troops assembled at sunrise …”

I got up and joined Murphy, who by now was wiping his forehead.

“It is hopeless. Capa has met another Bonapartist. But I’ll be delighted to join you.”

We hurriedly left. My new friend, Mrs McL., was already somewhere else while I followed Murphy. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor were holding court in a sitting room, next to the great hall. My first impression was how the former king had aged. Small, thin, with a wrinkled face, he looked like an old jockey.

I was much more interested in the Duchess. Beautiful? No. Two biggish black warts on both sides of her face didn’t help. Her chic dress was a bit too loud with lots of white fur. Her figure: a flat chest and biggish derrière. But she was rather graceful.

Well-known American ladies were curtsying to her, which in my opinion was de trop. She wasn’t royalty. When my turn came I simply shook hands with her, while Murphy made the presentation. Perhaps because of that I was granted a couple more minutes. Then I saw her eyes. Then I understood her: those keen calculating eyes. While making my compliments I had a momentary impression of a sleek benevolent snake. Well, my dear, I said silently while smiling, you hardly can be anyone’s friend. Then Murphy took me over to the Duke, who in his high-pitched voice asked me if it were true that Capablanca never practised.

“Yes, indeed, Sir”, I said, making a small curtsy, “he never practises”. Apparently he wished to ask more questions, but the salon became so overcrowded that Murphy escorted me back to Capa.’

The following occurred during the couple’s stay in Belgium:

‘One day Capa and I drove out of town to a farm famous for its capons, which always had to be ordered a few days ahead of time. When the capon was finally delivered to our apartment, Capa was delighted. “This bird is magnificent. I shall cook it myself.”

Our help was given a day off and Capa busied himself in the kitchen. The preparations were elaborate. Capa, a gourmet, was also a chef par excellence. Friends joked that he could make more money as a maestro of the cuisine than in chess.

When the capon was finally in the oven, Capa and I sat in the living room talking. Every now and then he would get up and go to the kitchen to watch the progress of the capon while basting it with some excellent brandy.

The telephone rang; one of our friends called about the success we had had at some diplomatic party the night before, especially elaborating on the compliments bestowed upon me. Capa’s mood darkened. “The compliments were exaggerated”, he said as he hung up the receiver, “and out of place”. Then suddenly he accused me of provoking undue attention. He remembered the way I looked at the man sitting across the room from us – some ambassador from a small country.

I grew indignant since, being near-sighted, I could not even see the face of the man. While I hotly responded to this unfair critique, Capa grew angrier, going into a long diatribe about a great lady’s behaviour which I didn’t quite maintain.

I sat proudly silent as he walked up and down the room. Some hissing sounds came from the kitchen, getting more insistent. I had an idea that it was an SOS from the cooking capon, but remained silent. As the hissing grew louder Capa paused a second, then madly rushed into the kitchen. Noisily the oven was opened. Then came a deep silence. I tiptoed after Capa. He stood before the oven contemplating a black carcass, the capon burned to a crisp. We looked at each other then laughed as we both sat on the floor before the stove. We laughed and kissed, and Capa said that he would take me out to the very best restaurant in Brussels.’

Elsewhere Olga Capablanca referred to a paella lunch with Andrés Segovia and the pianist José Iturbi in London in 1937, as well as the following incident:

‘I believe Capa would have been a fine musician, had he ever studied the violin. It wasn’t just a coincidence that among his friends many were celebrities. How keen Capa’s ear was could be illustrated by this little episode. We were in Paris, staying at the Hôtel Majestic, which belonged to one of Capablanca’s faithful admirers, Monsieur Taubert. One morning while we were having coffee in our suite a couple of piano chords sounded on the flight above us.

“What a nuisance, a pianist right on top of us!”, I exclaimed.

“A great musician”, said Capa.

“How would you know that? Just a few notes were played.”

“By the way they were played.”

I forgot about this incident until we went downstairs. As we passed by the desk I asked the clerk somewhat capriciously, “A person who came to stay above us, is he a professional pianist?”

“Indeed, Madame”, said the clerk smilingly, “and by the way, your compatriot.”

“Who is he?”

“Monsieur Rachmaninov, Madame.”

I swallowed hard before telling Capa, “You were quite right”.

Another well-known musician often came to join us at dinner. I well remember the bell boy paging us nearly every evening: “Mr Prokofiev is waiting…”.

Luckily we were all soon to depart to other destinations. I had not enjoyed Mr Prokofiev’s company. He was rather what in those days I called a “sourpuss”. I don’t think he liked me either, for I represented a bit of old Russia, which he officially hated. A couple of times we had arguments. If I were to compare him to someone I would think of Alekhine. The same tinge of nastiness in a rather colorless face.

Capa’s taste in music was much stricter than mine. Bach was his favorite, then came Mozart and Beethoven, while I preferred more modern composers, Chopin, Rachmaninov, Grieg, Debussy, etc. We both adored symphonic orchestras, but while I was indifferent to chamber music, in Capa’s opinion the string quartet was music’s highest expression. Neither of us cared for jazz.

Capa never danced. I imagine this had something to do with a rather prudish aspect of his nature, his penchant for privacy, his remoteness. He admitted he didn’t care to see me dance because some familiarity was unavoidable in the way people danced together. I had never danced since, although previously I could have danced all night. As ever, I was cautious not to do anything that could irritate or upset him. Those of us who cared for Capa realized that he should be treated with the utmost consideration, not only because he fully deserved it but also because of apprehensiveness about his high blood pressure, which made his extremely sensitive nature dangerously affected by aggravations. Although to the very end I did not know the extent of his fragility, I always felt that he should be spared all possible annoyances.

Unfortunately I had no control over things outside our house. Certain aggravations caused to Capa in the last few months of his life precipitated his end. He spoke of this himself, and such was the opinion of his physicians, as both of them have written to me.

He was not religious. He did not believe in God “officially”, but he did really. Cleanliness, moral and physical, were among Capa’s outstanding characteristics. Immaculate, almost dainty, in his personal habits, Capa never used dirty words; nor did he like promiscuous stories. Even gossip of any kind was distasteful to him.

Capa was always well groomed and well dressed, as the English newspapers had often mentioned, which perhaps was partly due to his sober taste, and also to the fact that his clothes were always made by the same Savile Row tailor shop. I believe Capa went to the same London tailor for about 30 years, from father to son. Yet Capa possessed only the most necessary outfits that his position required, everything of excellent material, finely cut. As he said himself, he “never bought junk”. That in the long run served him well, since he was light on his clothes, and they seemed to be enchanted against wrinkles or dust. Also it helped that he had a good figure. He held himself erect, the posture of his head superb, his gestures well proportioned, those of a man used to public appearances. He was the type who made his clothes look better. His hat Capa changed only when it was completely worn-out; nor did he wear it at a becoming angle, turning down the brim. “I don’t wish to look like a gigolo”, he would retort to my persuasions. Capa’s only weakness was his ties. He would take a great deal of time choosing them. Conservative, they were beautiful, made of fine heavy silk and the latest design.

The elegance of Capa’s appearance was enhanced by his hands. Truly aristocratic. Small, exquisitely shaped, and velvety like a kitten’s paws. So vividly can I remember the touch of his fingers, comparable to the delicacy of a small child’s touch. Yet there was no weakness about those intelligent hands, capable of doing a variety of useful things. And whatever he did bore the mark of fitness and precision. He could cook divinely. He made packages swiftly and accurately like a candy-store clerk. It was a pleasure to watch him pack for traveling. His handwriting was calligraphic, every letter beautifully drawn, even if written in a hurry.

Capa was a strong billiards player. I

heard an expert say that if he had devoted more time to the game

he would have been a champion. The same was said about his tennis

by one of the leading players on this continent. Capa could row

like a professional and was an excellent driver; his reactions

were instantaneous, which was important for he was inclined to

drive very fast. I had heard that in his college days, at Columbia

University, he was a promising young star, already sought by the

Big League, in baseball.’

Here is the letter (referred to above) regarding the Capablanca v Tartakower game (C.N. 1383):

‘28 April 1987

Dear Chess Friends,

Among the multitude of games played by my late husband, Jose Raúl Capablanca, there is one that has never been published nor even seen by anyone except the three of us: Capablanca, Tartakower and myself.

In the years that I had known Capa he had never played in private, he had never practised, nor even had a chess set at home. Ever so different from the chess masters all over the world!

This was, however, a very special occasion. It happened in Paris. I believe the year was 1938. We stayed in the Hotel Regina, Place Jeanne D’Arc, quite near the Louvre Museum. I had one of my frequent bad colds and stayed in bed to recuperate, when Savielly Tartakower, one of our good friends, came over for a visit. He stayed quite a while. Then suddenly he said to Capa: “I have a chess set with me. Why not play a game?” [Update on 14 March 2012: Christophe Bouton (Paris) points out that the hotel is located at the Place des Pyramides, and not the Place Jeanne d’Arc.]

Much to my astonishment, Capa smiled. “Why not? We are in good company.” He grabbed some of the hotel stationery, a small table was moved close to my bed and the two masters sat down to play. How long the game lasted I couldn’t quite tell, as here and there I slept a little. I remember Capa woke me up by gently touching my shoulder, to give me a few folded sheets of Regina stationery, on which he had written the score of Capa v Tartakower. Of course he won.

“Here is a present for you, chérie.”

Gingerly I took the folded stationery. “But you know I don’t understand a thing about chess.”

Both he and Tartakower laughed good naturedly.

“Take it and hide it well. Some day in years to come it will buy you a beautiful bijou”, Capa said. “Ever since I was a child everything I did was written down. And this is the only chess game that is only yours.”

Anyone wishing to buy the Capablanca jewel, as he referred to it, should write as soon as possible to: Mr Edward Winter [...]. 30 September would be the appropriate time limit, as I have authorized him to receive the bids on my behalf. In view of the exceptional nature of the game and surrounding circumstances, no offer under $US 10,000 will be accepted.

With sincerest good wishes to all chess players in all lands.

(Signed)

Olga Capablanca Clark’

Although the Cuban moved effortlessly in high society, Olga Capablanca also stressed the ease of his dealings with ‘ordinary people’:

‘Mr Fliegelman, we called him Fligu, was perhaps Capa’s most intimate friend, and probably Capa’s favorite one, for he was indeed completely devoted to Capa. Fligu was a typical Russian Jew, rather ungoodlooking but possessing tremendous charm, and it was impossible not to like him.

Capa told me that children always ran to him whenever they had cut or bruised themselves and would let him apply iodine uncomplainingly. “They trusted me. It was for their own good, even if did sting a bit.” He believed in the necessity of taking one’s medicine when needed. Anyone who knew him would soon learn to trust him implicitly. He was incapable of telling a lie.

Exacting, choosy, circumspect, these were characteristic traits of Capa, yet frequently he would show unusual consideration when it would have been natural for anyone to flare up. I remember how ready I was to burst into anger when a hotel servant rather carelessly broke a bottle of my precious perfume. Capa stopped me before I said a word. “Don’t you see, chérie, he is terribly upset.” The boy was sent out of the room with an extra tip. Well, he didn’t look downhearted. And, of course, I got another bottle of the same perfume.

Capa knew what to say to the elevator men to make them beam. He knew how to talk to the hotel clerks or to ship attendants to get the best of service and accommodations. He did not give large tips or permit any familiarity, yet every one of them would be eager to win his appreciation. There was about him an indefinable aura of superiority that distinguished him wherever he went. His presence drew attention. Even at large receptions invariably the most important would be drawn to him.’

It was also mentioned that Capablanca’s skills were not limited to relations with human beings, as was shown when he bought her a chinchilla, which they named Katchushko:

‘Capa playing with the kitten was a most charming scene to watch. They understood each other perfectly, both with grace and swift movements. Without apparent effort Capa taught the kitty to bring back the paper balls he threw forth. Katchushko would perform endlessly, fluffy little tail up and making little meows asking for more. “I’m tired of playing with you”, Capa would say, and still throw another ball. In no time Katchushko learned to stand up on his hind paws, serving like a little soldier, and also giving his tiny paw. Capa used to say, “the most intelligent cat I’ve ever seen”. No doubt he had the ability of a trainer.’

Much of his spare time was devoted to books:

‘His favorite pastime was, with the exception of detective stories, which he loved, reading history and philosophical essays. A book on military strategy would absorb him for hours. Capablanca was always interested in the stories of my Russian past, especially in the great Grand-Papa, Generalissimus Count Evdokimov, the conqueror of Caucasus, who had vanquished the Muslim leader, someone like Khomeini called Shamil. My people had been military since the time of Ivan the Terrible. Capa never tired of listening avidly to these stories, asking for more and more. Capa mentioned many times that his father was a man of tremendous pride with a fiery temperament. Very difficult to get along with. Explosive as a keg of gunpowder. Capa was the son and grandson of Spanish officers, and my strict military background became the key to our future relationship. We both belonged to the same caste, which gave us the feeling of propinquity, later developed into love.’

As regards the game that had brought him worldwide fame:

‘I don’t think he loved chess. Almost resentfully he said that if chess had not so grabbed him, he would have studied music, or perhaps medicine. So multifaceted was he that I believe he would have been a leading star in whatever field he chose.’

Because of the Cuban’s fine appearance and presence, it was not widely realized that he suffered from ill-health:

‘We already knew from Doctor Gómez’s instructions that Capa had to be careful about certain foods. What was most important was that he had to avoid anger and irritation. Alcohol was not recommended, but Capa liked only a little wine. The most menacing was the part dealing with aggravations, for at the time he was confronted with some nasty ones in connection with his divorce. He faced up to some unfair demands and actions.

The main cloud on our horizon was Capablanca’s marital status. He made no secret of it, having mentioned, soon after we met, his former marriage; it was ended de facto quite a few years previously. There was incompatibility of character, and he had always traveled a lot. Adored and pursued by women, naturally, he had had many infatuations, none of them too serious. His wife, too, had another man in her life; there were two teenage children and, of course, he took ample care of them all. But he simply had not bothered about divorce, since he definitely intended never to marry again.

After we met he had abruptly changed his mind. His entire outlook on life had changed. For the first time he experienced a feeling he had not known before, and it was most powerful. Especially since it came after the bleak years that had followed the debacle in Buenos Aires. Indeed, he had not lived a full life ever since, but now in the surge of new emotions he felt capable of recapturing himself and returning to great chess. His eyes sparkled, and I so remember the time he told me, “I shall recapture my crown for you”.

It was about then that he spoke to his wife. Direct and sincere, he told the truth, his intention to marry me, and he asked her for a divorce, offering the most generous conditions he could afford.

A gentleman, he could not envisage the adverse effect produced by his sincerity. The very thought of him being so in love as to wish to marry again made her furious. That was a shock, but he hoped that in time she would understand and come to terms, especially since under Cuban laws he could enforce certain issues. I said that, rather than that, I would wait with him. We both knew that his growing chess activities would mean more traveling and therefore more separations; it was essential that I should come to Europe and join him whenever that would be possible. He would introduce me as his futura, his fiancée, his future wife.’

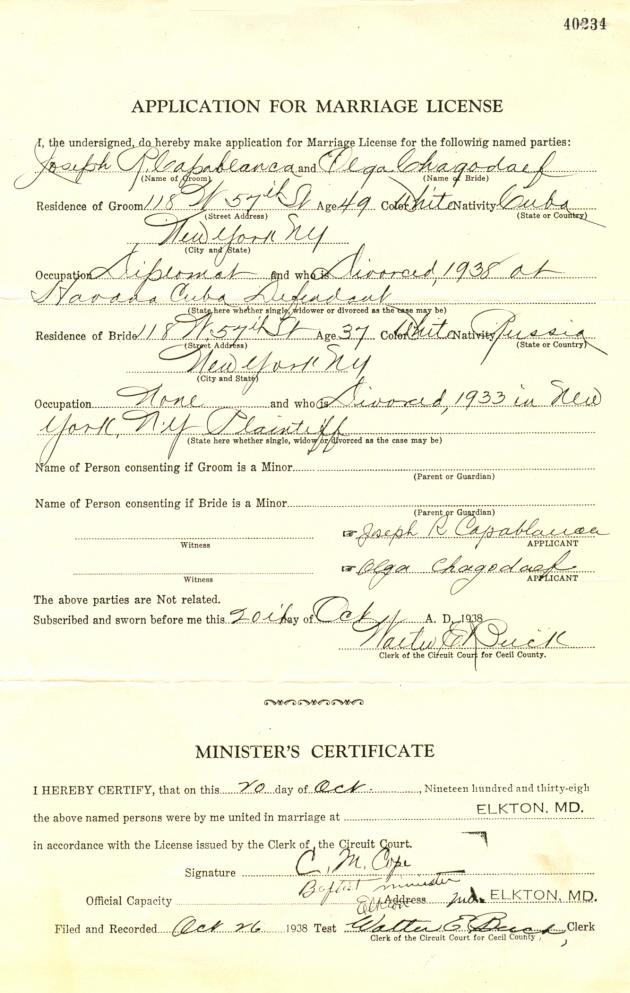

The couple were married in the United States on 20 October 1938. Below is an article contributed by Olga Capablanca to Chess Notes in 1988 (C.N. 1541):

‘This happened on our wedding day. Capa and I, just married, stood holding hands before a crowd of friends, well-wishers and the press; photographers were clicking away. The usual exclamations poured upon us.

“What a beautiful couple! Serenely happy – how long have they known each other? Didn’t she come from Russia some time ago? – Please look this way ...” Of course no-one could imagine the abyss of difficulties we had to overcome before we came to that day.

This was a crowded day, especially because next morning we were sailing to Europe, Capa being eagerly expected for the opening of the AVRO tournament in Amsterdam. Still, we managed to have a few minutes by ourselves. “Had to get rid of everybody”, Capa said as we walked for a while in sunlit streets.

Strangely enough, my memories of that day from then on become clear and whole as if they had been wrapped in cellophane to be preserved with all the details.

Capa suddenly stopped before a fine jewelry store. “Let’s go in.’ To the mute question in my eyes he only smiled. At the entrance the proprietor of the store, a famous collector of Russian antiques, greeted us enthusiastically. He and Capa had become friends in Moscow. Apparently we were expected.

“Ha, the greatest chess genius in the world, congratulations!” He embraced Capa, then kissed me. “Not only am I Capablanca’s humble admirer, I also love him. My very dear friend. So I have done my best, as promised.” He winked at Capa. “Your bride is as lovely as everyone said ...” At his sign an ornate flat box was brought and opened before me. There, shining softly on black velvet was the most beautiful jewel I had ever seen, a great brooch – better to say an ornament. Enormous diamonds, as big as my nails. Pearls as large as the greenest emeralds.

“Fit for a Princess”, said a man in our group. “A beautiful one”, said our host, Capa’s friend.

“Take it, chérie’, said Capa. “This is my wedding gift to you.”

Speechless, I stared as he put it in my opened hand, the most beautiful jewel, as big as my palm, as it lay there, shining into my eyes. “Personally selected by me for the great Capablanca, who indeed had approved – anything for my friend”, our host was repeating. Strangely enough, his words sounded quite distant. “You look white, chérie, are you all right?” Anxiously Capa was touching my shoulder. “Are you tired?”

“Oh, I am fine”, I heard myself saying through some roaring in my ears, like the echo of ocean waves, the moaning of wind. Such a pitiful sound ... was it the wind? I shook my head then gently returned the jewel to its box. “She is overwhelmed”, Capa’s friend said indulgently.

With a jolt I came out of my dream-like state. Back to reality. My husband was giving me the most beautiful jewel, a divine jewel. But ... I could not take it. As simple as that. I could not. No use discussing it; the preoccupation now was how not to hurt his feelings. Think fast, act bright, I ordered myself.

“Mon amour”, I said coming close to Capa and looking into his gray-green eyes, “I’ve another idea for my wedding gift. Our wedding. Our gift. Something both of us could enjoy. I’ve in mind a new car. A Packard, a gorgeous new car. And to think that most probably it would cost less than this jewel. Too magnificent. It’s only for special occasions. And since we travel so much it would have to be left in safety boxes – hotels, ships and legations. We’d have to worry about it. And just think, a new car could take us across France. We could go to the bord nord de la Loire to see the castles. That’s what you wanted to do ...” I spoke fast, eagerly, conscious of reaching his soft spot. Tenderly I kissed him, then turned to our famous jeweler friend. “No-one should make sacrifices on my wedding day. I do realize you were ready to lose money on this sale. But even then Capa isn’t quite in the position to buy this jewel. On yes, I know, not even for a friendly price.”

So be it. I had talked myself out of that gift, that jewel.

For the time being, things worked out beautifully. The new Packard made heads turn wherever we drove through la belle France. We visited the old castles along the Loire; this was our best trip.

When the time came to depart to Argentina, Capa decided to leave our car at the Cuban Legation in Paris.

Before long, War was declared. Panic in Paris ensued. Evacuations ... We never saw our car again. Neither have I learned what happened to the jewel I had refused. Such a beautiful jewel:

Many months later, in New York, I told my sister this story. She listened attentively to the end. After a little silence I added placatingly, “I imagine no-one else in the world would have done what I did.”

“That’s for sure”, she said. “And I don’t mean it as a compliment.”’

The AVRO tournament began three weeks after Capablanca’s wedding.

‘My memories of AVRO are gray. True, we arrived in Holland just after we were married, with the rewarding realization of having achieved the pinnacle of our most cherished wish. Nevertheless, somewhere in the background of our sensitivity lurked the shadow of regret – we were one day late for the opening of the tournament.

Capa had arrived from Havana in New York with considerable delay. I had spent some anxious days knowing how this would affect him, so meticulously precise in all his activities. I had not ventured any questions, but he mentioned the aggravations caused by Cuban chess groups and some domestic complications, no doubt related to his recent divorce. Those annoyances must have been grave enough to make him come late even to our wedding. We had to be married – the newspapers called it elopement – in Elkton, Maryland, where some formalities could be skipped, instead of having a beautiful formal ceremony. Already the next day we had to start on our trip to Europe, still one day too late.

Perhaps I already felt the shadow of a presentiment overhanging, but I had no idea of the precarious state of Capa’s health and how dangerous his high blood pressure could be. Much later, when we were in Paris, Dr Domingo Gómez, Capa’s principal physician, told me that Capa should not have played in that AVRO tournament at all.

In the latter part of [his second

game against Botvinnik] Capa suddenly got up and quickly went out.

I noticed that when he returned his face had a rather grayish

pallor, although he continued the game to its end. He graciously

surrendered to Botvinnik, shaking his hand with a smile. Later he

told me he had had blackness before his eyes when he rushed out,

to throw some cold water on his face in the wash-room. As was his

rule, he offered no excuse or explanation, merely saying,

“Botvinnik played well and I did not”. I was the only one who knew

how unwell he was at AVRO.’

The following is a slightly abridged version of an article which Olga Capablanca contributed to Chess Notes in 1987 (C.N. 1435):

‘Capa smiled rarely, but when I think of him it is his smile that I first recall. It lighted his face, bringing out all his attractiveness – like a glow inside a fine porcelain vessel. If only for a few seconds, it permitted a glimpse into his inner self, something he preferred not to display, the deep sensitivity of heart which, nevertheless, was one of his outstanding features.

Someone’s misfortunes easily aroused his compassion and willingness to help, and sometimes he would not even mind going out of his way. It made no difference what refugee he helped. I found out indirectly that through his diplomatic connections many Jews obtained visas and were able to escape into the free world.

I especially remember a White Russian refugee, formerly an important General, a member of the last Imperial Staff. He was now old and sick, making his living in Paris by earning small commissions; I bought my perfumes through him. This is how Capa met him during the busy last few days before our departure from Europe.

The results surprised me: Capa found time to drive him to the other end of the city to the hospital, to secure for him a series of treatments, pay for them and the medications he needed. To top it all, he invited him for dinner, which, I believe, was the greatest thrill for the old man in years.

To have dinner with Capablanca was not an ordinary occurrence. As a rule, he refused most invitations. That very evening Capa invited the old General out; he broke off, much to my regret, the invitation to a ball in a magnificent château in Chantilly. We dined instead in our hotel discussing various aspects of military strategy. I had no heart to complain. While Capa preferred to abstain from most social activities, except of course the official ones, sometimes he would surprisingly accompany me to some modest home of my exiled compatriots. He chose people on the basis of what they personally represented to him, regardless of their worldly positions. It must be said, however, that most of them had distinguished themselves in some particular field.

Impatient and spoiled as he was, Capa made exceptions for children and old people. Soon after we met he asked me, “Would your mother like to go to the zoo with us?”

“Oh, I’m certain she would, but she hardly expects to.”

“A beautiful day, today”, said Capa, “and I suppose she isn’t often invited to a zoo.” Indeed, Mama wasn’t.

But that day was spent to her heart’s delight. Capa measured his fast stride to her slow steps. We sat on all the benches she wanted. Capablanca explained to her everything she wanted to know. And he could tell a lot, being extremely fond of animals, especially wild ones. Tigers and lions were his favorites – he always bought books about exploring the jungle. In this aspect as in many others, our tastes were similar. Many of our hours were spent in front of their cages in the zoos of various countries.

A significant part of my memoirs should be devoted to animals. It is quite possible that if at the gates of Heaven all kinds of witnesses were accepted, in the motley crowd testifying for Capa there would be quite a few stray kittens and pups that knew the luxury of sharing his meals. He could never be callous to the suffering of anything alive. A typical remark of his comes to my mind: “Quite an uncomfortable thing at times, to have a conscience. But what if I have it!”

There is so much to tell if one lets the memories fly in, clinking their transparent wings at the passage of years. Their meaning is simple: part of human life should not vanish into oblivion.

One day particularly stands out in my memory: 14 July in Paris, which is always an event, but this was a particularly important one: Germany and France had signed a non-aggression pact. Everyone was jubilant. A magnificent parade was staged, later referred to as “The Last Parade of France”.

Capa and I had tickets for the Presidential tribune, but we were delayed at luncheon. When we started towards the avenue des Champs-Elysées, we found all the adjacent streets so crowded we had to park our car several blocks away. Then came the problem: how to get to the tribune? People stood packed as thick as a wall. Crowds had always frightened me, but this was the worst one I had seen. While the American crowd as a rule is good-natured I discovered that “the most polite people in the world” made a crowd surprisingly rude and mean. This was quite a shock. “Sales étrangers” (“dirty foreigners”) was the meekest of their remarks. No-one would move. No-one would pay the slightest attention to our tickets which Capa showed, not even the agent (policeman), no less unpleasant than the rest: “I don’t give a damn about your tickets!”

I caught at Capa’s sleeve. “Let’s go away, let’s not even try it. Never mind the parade.” But just about then Capa lost his patience. He stuck the tickets back into his pocket. “Make way!”, he commanded. I still don’t understand how he did it. The crowd receded enough to let us pass. As in a dim nightmare I remember nasty faces, hissing as we moved ahead. When finally we reached the benches of the tribune I fell on my seat pantingly. “What is the matter with you, chérie?”

“I was afraid any second they would tear us up.”

Capa shrugged his shoulders. “You shouldn’t be afraid when with me.” ...

That very night we were invited to a great ball at the Palais de l’Elysée given by the President of France in celebration of the non-aggression pact just signed. As Capa and I stood for a while in the Presidential group, Herr von Ribbentrop, bemedaled and benevolent, was introduced to us, a polite smile playing on his pale, sharp face, not unattractive. I remember an unexpected pang of melancholy. Suddenly I found myself thinking, “all this seems to be a spectacle ... children playing ... but dangerously. How much of this is serious?”

I turned to Capa, a few steps away. “What is the meaning of this pact?’, I asked him. For a moment he squinted his green-gray eyes, looking into the distance. “The meaning of a pact is usually revealed the day it is broken”, he said and led me to the champagne table. ...

Capablanca had two scintillating careers, that of a great chess master famous all over the world, and that of a diplomat vastly popular in both hemispheres. These careers required constant moving and, as we travelled, first class de luxe accommodations were always provided for us. Indeed, one could easily become accustomed to chauffeured limousines, embassies, VIP suites, great ships and famous hotels – all those complimentary tributes to Capa’s fame.

Speaking of his other career, in the diplomatic world, I soon learned about its different aspects. The charming people in lovely salons had problems of their own, besides the changing political moods. Their salaries were comparatively modest, especially those of the representatives from small countries. There was a constant struggle to keep up front in their embassies. No wonder the diplomats as a rule were selected from the wealthy class. The career diplomats were rather few, appointed for some outstanding capacities. Capa belonged to that group, having no personal fortune to speak of, but carrying many obligations in his homeland.

A chess career was not a lucrative occupation. The tournaments and matches, while attracting the world’s attention, were not money-making spectacles, for there was no charge for admission. Masters, though provided with traveling expenses, were not paid for their participation and could only hope to win prizes.

Pretty soon I realized that Capa, most generous of men, a gentleman of exquisite tastes and manners, was forced to curb his impulses, to watch closely his expenses. My own modest savings were soon spent. I had to manage on my small allowance. But never would I ask Capa for extras, adding to his worries. I loved him.

At the same time I knew how proud he was of my appearance, of my being well-dressed. He sometimes said of me, “She is the one woman who would look good in anything”. This, of course, wasn’t true. A typical man’s remark. But to disappoint him? Never!’

Olga Capablanca also wrote about her husband’s last tournament, the Buenos Aires Olympiad of 1939:

Some general chess disclosures:‘This was our last long trip, to the Torneo de las Naciones in Buenos Aires. We left Paris at the end of summer, 1939, and our first stop on the way to South America was Italy.

Italy charmed both of us. Rome was awesome, as I had imagined it. Even more than that. A certain déjà vu impression seemed to float about the old streets, the fountains, the palaces and churches, imparting to them some familiar aspect. Strangely enough, I felt more at home there than in Paris, which by then I knew quite well. As usual, we stopped in one of the finest hotels. Some officials came to see us. The next day was dedicated to seeing the Vatican. Our Embassy invited for us a charming guide, an Italian Count who knew all about Rome and especially the Vatican, where he took us first.

To describe my personal feelings would perhaps be too complicated a task. I would, however, mention an incident that so intrigued Capa that he spoke of it on different occasions. About the time we were in the midst of our excursion, dazzled by the surrounding magnificence, our guide suddenly remarked, “Madame Capablanca seems to know the Vatican as well as I do”. Capa looked at me with large eyes. Slightly embarrassed, I tried to explain: “I’ve read so much about these wonders, these paintings – and history – some of it remains …”

The charming guide shook his head. “I had an impression of a more intimate knowledge.”

“She is here for the first time in her life”, Capablanca said, a little sharply.

The Italian Count bowed to him. “I must admit this place incites one’s imagination.”

The incident was dealt with, but Capa still looked at me questioningly. He knew that I was inclined to believe in reincarnation – some of it related to the Vatican. So I laughed, and we talked of other things.

We remained in the Eternal City just a few more days, absorbing its many attractions, including the historic squares, the opera in the open air and moonlight rides in a horse-driven carriage.

Then our ship came, and off we were on our way across the blue waters of the ocean. Many lovely days followed. As we crossed the Equator I was impressed by Pernambuco, with its tropical atmosphere of dejection. After a few more spring-like days a gala dinner on the ship signified the end of our journey. We arrived in Buenos Aires. A crowd of friends awaited us at the pier. A delightful surprise was to see among them Carmencita, the wife of our Ambassador to Argentina, Ramiro Hernández Portela, one of Capa’s closest friends and the Dean of the diplomatic corps in that part of the world.

Capa and I had rented an exquisitely furnished apartment in the Plaza San Martín, as modern as one in New York but equipped with a few servants, including a car with a driver. Flowers were constantly sent to me in such profusion that, as a friend joked, my place looked like a funeral parlor.

Sometimes, when Capa was free of chess, our driver took us to horse races. I remember that once a magnificent horse named Capablanca was running. By a peculiar quirk of caprice, Capa didn’t bet on him. Then he smiled a bit embarrassedly when everyone rushed to congratulate him – the great horse just waltzed in.

“No, I did not”, he answered curtly. “But perhaps she did.” Well, I had very little money to bet, but I won enough to order a new hat.

This charming existence was, of course, darkened by an overhanging bleak shadow, ever since that September night when in the depth of it a cannon boomed. Both of us were awakened. Capa simply said, “The war is declared. The war with Germany.”

The idea was frightening but, to tell the truth, the beginning of war had little impact on Buenos Aires’ busy goings on. It was noticeable, however, in the tournament activities for the simple fact that the representatives of different nations stopped greeting each other, according to their political positions. That notwithstanding, the games continued as scheduled. At one time, Capa, the head of the Cuban team, was due to play against Alekhine. And Capa won. [In fact, Capablanca did not play in the Cuba v France match.]

That day an amusing episode occurred. One of Capa’s most ebullient friends, Dr Querencio, challenged Alekhine to a duel if he continued to refuse Capablanca a revanche match. Harsh words followed. Alekhine cut them short by running out to the men’s room and locking himself in. Undaunted, Querencio waited for him at the door. I was told that Alekhine had stayed in that bathroom for nearly an hour, until friends of Dr Querencio convinced him to leave his post. Only then had Alekhine carefully emerged and run away. This episode created quite a few laughs in Buenos Aires. But Capa merely shrugged his shoulders.

Then came the end of the Great Tournament of Nations, celebrated in the Teatro Colón, the largest in Buenos Aires, completely overcrowded this time. The prizes, the big silver trophies, were delivered one after another to each of the winning nations. There was only one single individual prize, for the highest score of all. The counting was still going on, practically to the end of the ceremony, when to great acclaim it was announced from the stage: “First prize, the one and only individual prize, is won by Maestro José Raúl Capablanca.” Thunderous applause lasted quite a while. [There were other individual prizes, but they may not have been distributed at the closing ceremony.]

Capa, elegant and smiling, went up on the stage to receive his prize, while I sat in our Embassy box with the Cuban Ambassador and his wife, Carmencita. Capa returned to us while the enormous crowd watched. Like a happy little boy he put the velvet box with the medal right before me. Applause followed. Everyone stood up as I pressed to my chest this glorious present.

Next day the Chess Federation called me up. The name was not yet engraved. “Which name would you like to have on the medal? The whole world saw that Capablanca gave it to you.”

“He is the one who won it, so it should have his name.”

This medal is still my cherished possession.

Soon afterwards we were scheduled to return to Cuba, where Capablanca was invited to play in a local tournament.

The last evening in Buenos Aires was divided between different appearances. I had joined Capa to bid farewell to all the chess participants in the tournament. As he and I were separated for a while by the crowd, a few chessplayers came around me. They begged me to ask Capa why he didn’t pay more attention to chess. I promised to do my best.

That evening Capa and I had dinner alone in our lovely dining room. He was in one of his best moods and even drank a little champagne with me. Only then did I venture the question. “The players would like to know why you don’t pay more attention to chess.”

Instead of cutting me short, as I half expected, Capa smiled. “You, too, would like to know?”

As I nodded, he said slowly and clearly: “Because if I did, there would be nothing left for the others.”’

‘Capa was nostalgic sometimes when he talked about Cuba, the beautiful cheerful country of his childhood. He very seldom mentioned his past successes in chess. As a rule, he did not speak of chess. He was a very proud man. No doubt the loss of his crown involved great humiliation for him and suffering. We never touched that theme. It is true that Capa very much disliked Alekhine, to say the least, but he did not criticize his chess. I don’t think Capa ever gave up hope of getting another championship match. He described Lasker as “an old lion” and said of Euwe “irreproachable, but few fireworks”. Capa believed that Botvinnik would one day be world champion. “He is very strong and has the tenacity needed to get to the very top.” Sir George Thomas, I believe, was his favorite.’

During the Second World War, Olga asked her husband who the best generals were. ‘Capa said, “MacArthur, Patton and Rommel.” I said, ‘But Rommel is German and we are at war.’ Capa shrugged his shoulders. ‘That doesn’t change the fact that he is a good general”. So typical of Capa’s fairness in judging himself and others.’

Their marriage lasted less than three and a half years, until Capa’s death in New York at the age of 53:

‘Mount Sinai Hospital, 8 March 1942. Capa was unconscious. The doctors said a last-hope operation was to be performed on him. They suggested I go out, perhaps take a walk. I would be called if needed. Then I was in the street near the hospital entrance. A few steps to the corner. I stopped as I saw a star in the twilight sky. What time it was I didn’t know. The star seemed to have a second of special brightness. But it suddenly went out. And the mist darkened. There was a special silence in the sky. In the street. In my heart. I knew that Capa had died.’

As a postscript it may be mentioned that one of Olga’s great hopes, never fulfilled, was to see a motion picture of Capablanca’s life. In a letter received in May 1987 she wrote:

‘For the first time in years I have seen an actor who could play Capablanca. I am referring to that special look in Capablanca’s eyes concentrating on a problem. Jeremy Brett playing Sherlock Holmes had that blue distant look. It really shocked me – reminding me so of Capa.’

A number of the above illustrations, as well as the love letter from Capablanca, were given to us by Olga Capablanca Clark.

Francis E.W. Ogle (Medwood, NJ, USA) reports that Allen Kaufman had a letter printed in the New York Times of 13 April 2007 which related a story he had been told by Olga Capablanca:

‘Capa was playing in a tournament in Russia in the 1930s. Some of the best in the world’s best [sic] were competing, including Soviets and foreigners. A famous personality arrived to watch the event: Stalin.

The dictator approached Capablanca and asked, “How do you like my tournament?”

Capa replied, “It’s terrible; your players are cheating.”

Stalin: “What do you mean?”

Capa: “When they play against each other, the Soviets make quick draws and they get to rest. When they play against me, they fight on and on just to make me tired.”

The cheating stopped immediately.’

Our correspondent notes that Capablanca’s complaint to Stalin was referred to on page 212 of A Chess Omnibus. Olga Capablanca mentioned such an incident to us a number of times (in writing and orally), and below we reproduce verbatim what she wrote to us on 26 July 1989:

‘It is little known, I believe, that Stalin came to see Capablanca play, hiding behind a drapery. This happened in Moscow in 1936. Capa had mentioned it to me en passant, so I am a bit hazy about the details, such as who had accompanied Stalin – seems to me it was Krylenko. However, the gist of this encounter remains quite clear in my mind.

Capa said to Stalin: “Your Soviet players are cheating, losing the games on purpose to my rival, Botvinnik, in order to increase his points on the score.”

According to Capa, Stalin took it good-naturedly. He smiled and promised to take care of the situation.

He did.

From then on the cheating had stopped and Capablanca had won the tournament all by himself. This was an important conquest, proving to the world that Capablanca returned to his own great form.

As he told it to me Capa added: “I had promised you to be again the best chessplayer in the world. So I have done it for you.”’

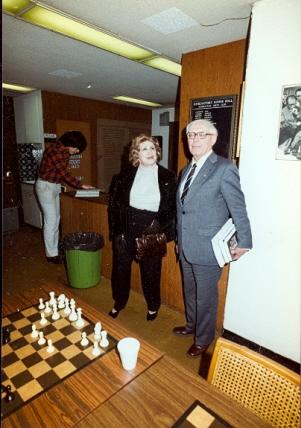

Below is a photograph of Olga Capablanca with Mikhail Botvinnik which she sent us in the 1980s:

(4950)

Regarding the above-mentioned Capablanca v Tartakower game, a footnote on page 181 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves mentioned that in 1998 we were unaware of the document’s whereabouts. Subsequently (see C.N.s 5323 and 6687) we learned that the score-sheet had become part of the collection of Mr David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA).

It will be featured in Mr DeLucia’s forthcoming work, a two-volume set entitled In Memoriam, and we are most grateful to him for allowing the game to appear for the first time here, in the present C.N. item:

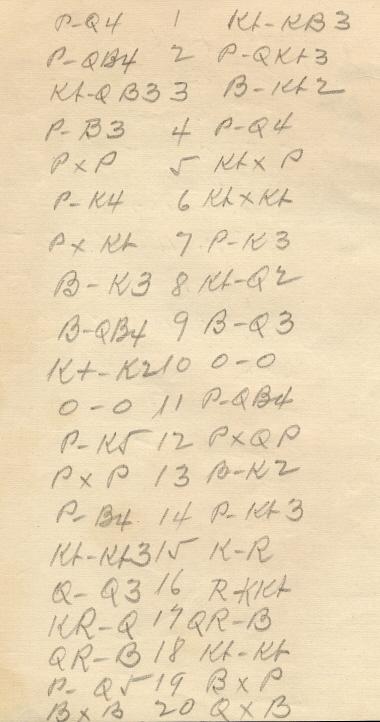

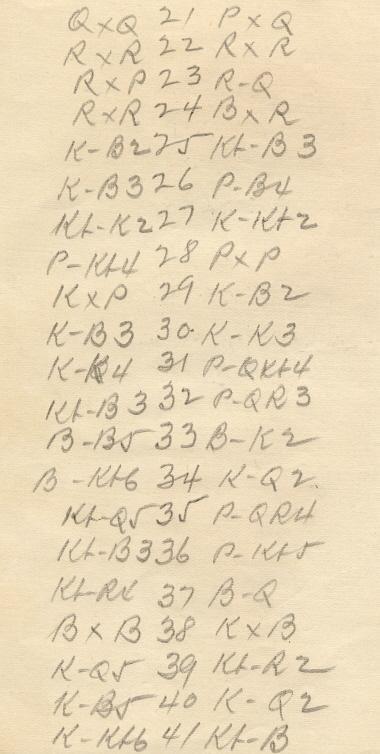

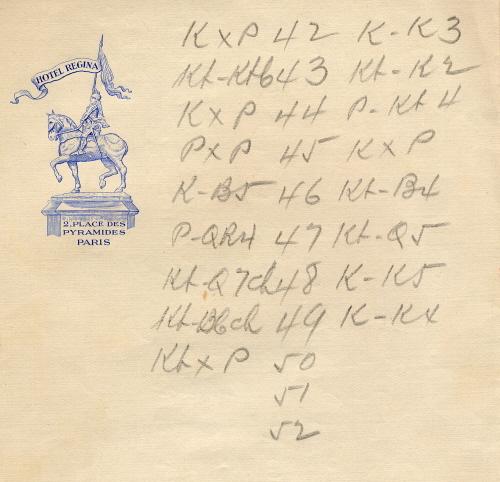

José Raúl Capablanca – Savielly Tartakower

Paris, circa 1938

Queen’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 b6 3 Nc3 Bb7 4 f3 d5 5 cxd5 Nxd5 6 e4 Nxc3 7 bxc3 e6 8 Be3 Nd7 9 Bc4 Bd6 10 Ne2 O-O 11 O-O c5 12 e5 cxd4 13 cxd4 Be7 14 f4 g6 15 Ng3 Kh8 16 Qd3 Rg8 17 Rfd1 Rc8 18 Rac1 Nb8 19 d5 Bxd5 20 Bxd5 Qxd5 21 Qxd5 exd5 22 Rxc8 Rxc8 23 Rxd5 Rd8 24 Rxd8+ Bxd8

25 Kf2 Nc6 26 Kf3 f5 27 Ne2 Kg7 28 g4 fxg4+ 29 Kxg4 Kf7 30 Kf3 Ke6 31 Ke4 b5 32 Nc3 a6 33 Bc5 Be7 34 Bb6 Kd7 35 Nd5 a5 36 Nc3 b4 37 Na4 Bd8 38 Bxd8 Kxd8 39 Kd5 Na7 40 Kc5 Kd7 41 Kb6 Nc8+ 42 Kxa5 Ke6 43 Nb6 Ne7 44 Kxb4 g5 45 fxg5 Kxe5 46 Kc5 Nf5 47 a4 Nd4 48 Nd7+ Ke4 49 Nf6+ Ke5 50 Nxh7 1-0.

(7497)

As reported in C.N. 3002, on 11 April 1988 Olga Capablanca sent us this photograph of her with Kasparov which had been taken in New York earlier that year ‘at the small reception I gave in my apartment’:

Addition on 8 September 2023:

Further to the above-mentioned article on Nottingham, 1936, see too the November 1945 CHESS and the 1 November 1946 Chess World. From the last of these (page 219) C.N. 505 quoted what Olga Capablanca wrote about her late husband’s AVRO game against Botvinnik:

‘Capa, too, was an unusually good loser ... I shall never forget how he enjoyed losing his game to Botvinnik in the Holland tournament. When the two shook hands after the game Capa had such a delighted face that I believed he had won, since his position had been strong to the end. Not until I approached him did I learn that he had lost. He said, “It was a pleasure to lose to Botvinnik, he played so well. He misled me completely. I thought I was winning. Very clever ! Very good!”’

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.