Edward Winter

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Bb4 5 O-O O-O 6 d3 d6 7 Bg5 Bxc3 8 bxc3 Ne7 9 Nh4 c6 10 Bc4 Be6 11 Bxf6 gxf6 12 Bxe6 fxe6 13 Qg4+ Kf7 14 f4 Rg8 15 Qh5+ Kg7 16 fxe5 dxe5

17 Rxf6 Kxf6 18 Rf1+ Nf5 19 Nxf5 exf5 20 Rxf5+ Ke7 21 Qf7+ Kd6 22 Rf6+ Kc5 23 Qxb7 Qb6

24 Rxc6+ Qxc6 25 Qb4 mate.

Capablanca’s victory at living chess over Herman Steiner (Los Angeles, 11 April 1933) is often published, despite being described as ‘probably pre-arranged’ on page 115 of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975). Page 326 of our 1989 book on the Cuban said that ‘the chances must be high that the game was pre-arranged’, and since then we have found the following remark by Steiner himself, on page 66 of the March 1943 Chess Review:

‘... in reality it was pre-arranged by Capablanca, who at that time refused to play any other way. Naturally, I would like this known as it could not possibly be considered an Immortal Game.’

(2037)

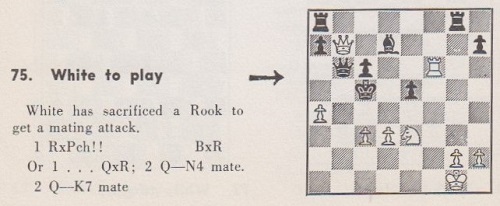

On page 130 of 1001 Brilliant Ways to Checkmate (Hollywood, 1969) [formerly published as 1001 Ways to Checkmate (New York, 1955)] Reinfeld offered this position:

The solution given was 1 Rxc6+ Qxc6 2 Qb4 mate, but on page 52 of the June 1987 Chess Life a reader pointed out 1 Qe7 mate. The Chess Life columnist, Larry Evans, might have been expected to know, and mention, that, with the (vital) difference of a white pawn on a4 rather than a2, the position was identical to the finish of Capablanca v Steiner, but nothing was said.

An additional twist comes from a game published on pages 4-5 of the March 1923 Wiener Schachzeitung:

Savielly Tartakower – A. Holte

Denmark, 20 January 1923

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e3 O-O 6 Qc2 Nbd7 7 Nf3 c6 8 cxd5 exd5 9 Bd3 h6 10 h4 Re8 11 Bf4 Bb4 12 O-O-O Qe7 13 g4 Nxg4 14 Rdg1 Ngf6 15 Ne5 Nxe5 16 dxe5 Nh5 17 Bxh6 Qxe5 18 Rg5 Qf6 19 Rxh5 gxh6 20 Rg1+ Kf8 21 Bg6 Bxc3 22 bxc3 Ke7 23 Bf5 Bxf5 24 Rxf5 Qxh4 25 Rxf7+ Kd6 26 Rg6+ Kc5 27 Rxb7 Rab8 28 Qb3 Rxb7 29 Qxb7 Qa4

30 Rxc6+ and mate next move.

(2189)

The Gambit, July 1930 (pages 189-190) contained an item dated 19 June which began as follows:

‘Lively interest of the picture world in the newly organized Beverly Hills Chess Club was emphasized last Thursday evening when Cecil B. deMille, the famous producer, sent in his membership and was elected to the board of directors.’

It may be recalled that he refereed Capablanca’s game of living chess (Los Angeles, 1933) against Herman Steiner (see page 115 of The Unknown Capablanca by D. Hooper and D. Brandreth).

(2848)

We see no reference to chess in The Autobiography of Cecil B. deMille edited by Donald Hayne (London, 1960).

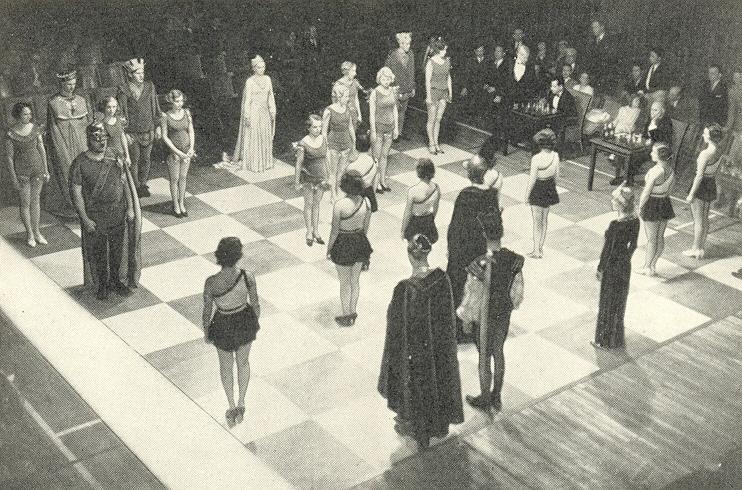

Below is a picture of the occasion, from page 132 of MD en español, September 1973:

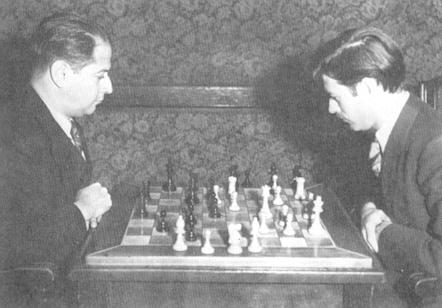

It is also worth noting the following shot, from page 31 of Famous Chess Players by Peter Morris Lerner (Minneapolis, 1973):

‘José Capablanca (left) meets with US chess master Herman Steiner (right) for an informal game of chess in Los Angeles, 1933.’

(4092)

Complementing the earlier items on the famous game of living chess between Capablanca and Herman Steiner in Los Angeles on 11 April 1933, we quote from local reports.

A feature about the Cuban on page 3 of the California magazine The Chess Reporter, April 1933 commented:

‘The chess public of Southern California owe a hearty vote of thanks to Judge Lippman of Santa Monica for his hospitality in entertaining Señor Capablanca and thus making possible the Exhibition and the “Living Chess” on Tuesday night and the receptions to the Masters at the various clubs.’

No further details were given, but the game-score and other information were provided by Clif Sherwood in his chess column in the Los Angeles Times of 16 April 1933, part III, page 7:

‘Former World Champion José Capablanca of Cuba gave his first exhibition at the Los Angeles Athletic Club, playing 32 boards, with 25 wins, six draws and one loss to Allen and Carlson in consultation. Tuesday night the Cuban opposed Herman Steiner, local expert, at the Athletic Club in a game with living pieces in costume, Cecil B. deMille refereeing. Capablanca showed his class in the most brilliant fashion.’

As noted in C.N. 2037, a decade later Steiner reported that the game had been pre-arranged. For the record, we quote, from page 66 of the March 1943 Chess Review, the full text of his letter on the subject:

‘In The Immortal Games of Capablanca, page 203, the introduction to Exhibition Game No. 93 states that this game “played with ‘living pieces’ turns out to be vastly entertaining and must have delighted the spectators”. This gives the impression that the game was played on its merits, when in reality it was pre-arranged by Capablanca, who at that time refused to play any other way. Naturally, I would like this known as it could not possibly be considered an Immortal Game.

Had Mr Reinfeld consulted me before going to press I would gladly have given him all the facts with proof thereof.’

(4051)

Below is another photograph, in which the Cuban is seated at a board in the top right-hand corner:

Source: page 57 of Alt om Skak by B. Nielsen (Odense, 1943).

(4684)

From John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA):

‘I have seen pictures of Capablanca and Steiner from Los Angeles 1933, but, until now, not this one with Cecil B. deMille:

It comes from the archives of Jacqueline Piatigorsky, whose chess mentor was Herman Steiner, and has been made available thanks to her family.’

It will be noted that Steiner has the white pieces. A detail of the position is provided.

(8030)

A fourth such position is added, from page 36 of Complete Book of Chess Stratagems by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1958):

See too page 37 of Reinfeld’s revised edition, The Complete Book of Chess Tactics (New York, 1961).

(9784)

C.N. 3454 (see too Chess and Hollywood) showed a small, poor-quality photograph of Capablanca at the chessboard with Finis Barton (1911-78). Now, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found another shot, on page 10 of Part II of the Los Angeles Times, 11 April 1933:

Can a high-quality copy of the photograph be found?

(11598)

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.