Edward Winter

Alexander Alekhine

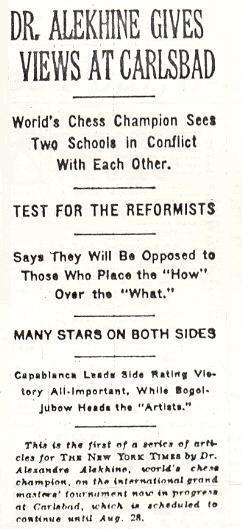

During the Carlsbad, 1929 tournament the world champion, Alexander Alekhine, wrote six reports for the New York Times, and the full texts are given below. Some of the language is unusual, and there is, for instance, occasional confusion over the terms game, match and tournament.

Article 1/6: New York Times, 1 August 1929, pages 21 and 23:

‘CARLSBAD, July 31. For the fourth time since 1907 the elite of the world’s chess talent is gathered here under the direction of that veteran master, Victor Tietz, for a stubborn four weeks’ combat. For the fourth time the chess world will follow the progress of the battle with the keenest anticipation, and after mature judgment will render its verdict on the results recorded.

The world-wide interest manifested in this masters’ tournament is wholly justified. Not only has it been organized on a generous scale – there will be 22 contestants – but it immediately precedes the new match for the world’s championship.

It also promises to develop into a determined battle between the adherents of two schools opposed in their fundamental interpretation of the essence of chess. One group is represented by the former world’s champion, José Capablanca of Cuba, who in addition to being a devotee of 64 squares is also fond of tennis and other physical sports. With him are two engineers, Géza Maróczy of Hungary and Dr M. Vidmar of Yugoslavia; the mathematician, Dr Max Euwe of Holland, and that well-known explorer of chess variations E. Grünfeld of Vienna.

For them the “what” of chess is more important than the “how”. Victory to them is the sole aim of the game. Only in rare instances, when their creative instinct masters their sporting will, do they become interested in the “quality”, and it then asserts itself in the practical application of scientific chess experience.

The outcome of the rejection of the creative aspects of chess could easily be foreseen. It resulted in the school of reformists, led by Capablanca, who feared that theory, highly developed, might result in a paralysis of the game and they therefore sought to revivify it through propagating a revision of the rules of play. Now, just what does this postulation mean?

First, an overestimation of the force of theory in a utilitarian sense.

Second, a disregard for the intuitive – the imaginative – and all those other elements which raise chess to the level of an art.

Third, it results in a general “shallowing” of the creative performance.

To just such a deadening level the reformist school, these pseudo-scientists, would reduce the noble game of chess, but fortunately there prevails a stronger oppositional force which first asserted itself in the play of Breyer and Réti, whose premature deaths were a distinct loss to the chess world. As representatives in the present Carlsbad tournament of their interpretation we name E.D. Bogoljubow of Russia, A. Nimzowitsch of Denmark, Dr S. Tartakower of France, E. Canal of Peru, F. Sämisch of Germany and E. Colle of Belgium.

These masters have succeeded in demonstrating that even in the realm of the newest theoretical accomplishments there still remains plenty of scope for the development of the imagination, temperament and will-power. To their achievements the game of chess, since the war, owes its unexpected advance.

One could fitly designate this group as the “neo-romanticists”, and they have been referred to as such, but they might also justly be called the “tragedians of chess” because, while the reformist will greet the mistakes of his opponent in a utilitarian sense, the neo-romanticist desires to carry his grand scheme to completion.

Right here enters that moment when the art of chess may be called the most tragic of all arts, because the chess artist, in a measure, is dependent on an element outside the scope of his power; that element is the hostile co-workers who through carelessness constantly threaten to wreck a flawless mental edifice. The chessplayer who aspires to demonstrate the “how” of the game will view the single point scored a poor offset for the failure to gratify his artistic yearnings.

The bent for creating often results in disappointments, but in the end the passion is victorious, and it is only due to the sacrificing powers of many enlightened chess talents, because their creative leanings have foregone professional careers, that the chess world will be freed of the superstitution [sic] of the reformists. Chess is not football.

Between the two groups of contenders for prize money in the Carlsbad tournament we also would mention the so-called “classicists”, primarily Akiba Rubinstein of Poland, then that apostle of the king’s pawn, Rudolph [sic] Spielmann of Austria, and last, but not least, the gifted but erratic American champion, Frank Marshall.

I met Mr Marshall and his wife in Paris a few days ago, and the sight of this impetuous, expectant warrior hastening to the battle arena filled me with a momentary jealousy and a regret that I was not to participate in the greatest post-War tournament since that of Moscow in 1925. But the rank of a world champion often demands abstention from the lust of battle.

Only eight days after the conclusion of the Carlsbad tourney I shall be called upon to defend my title. The challenger is no less a person than Bogoljubow, victor of the Moscow and Kissingen tourneys. Consideration for himself apparently did not prevent this grand master from entering the lists at Carlsbad, and in this connection the following must be taken into account: a challenger has much less to risk than the defender of the title.

Efim Bogoljubow

Bogoljubow says he welcomes such active training before his match with me as this tourney imposes. It will soon be demonstrated who is right, Bogoljubow with his reckless optimism or I in my determination to husband my powers by practice and a rigid abstention on this occasion. Will Bogoljubow be the victor in the Carlsbad event? Let us consider the chances all round. We already have named the chief contenders. It is not in the cards that a dark horse like Dr K. Treybal of Czechoslovakia, Karl Gilg of Germany or P. Johner of Switzerland or a newcomer like Miss Vera Menchik of Russia will carry off first honors, although they each will furnish a sturdy combat.

Will that very superior technician Capablanca turn the trick? His victory would, at least, mean a great gain for chess, for nobody can reach the top in such a world tournament with only drawn games to his credit. He would have to abandon his morbid theories. Or will Bogoljubow succeed for a third time in bowling over the former world champion?

In addition to these two favorites, two other grand masters must be reckoned with, A. Nimzowitsch of Denmark, who, after his failure at Kissingen, will make a determined effort to prove he still belongs to the elected few, and the young Dutchman Euwe, who impresses me with his briskness and learning.

Soon, very soon, the race will be past. In any event, a great spectacle awaits the chess world.’

Article 2/6: New York Times, 20 August 1929, pages 21 and 24:

‘CARLSBAD, Aug. 19. The development of a chess tournament and its sporting results usually depend in a large measure on the pace wherewith the tourney gets under way. The initial contests usually influence the disposition and humor of the combatants. In this respect the first five rounds of the Carlsbad tournament were symptomatic.

This tournament afforded the spectacle of a man winning five games running or scoring 100 per cent. He is a player who, despite his long and in part brilliant tournament experience in recent years, perhaps has been slightly underestimated. He did not win through the inattention or errors of his opponents but by virtue of precise and determined mental effort. On the other hand, we witnessed in the course of these opening rounds how a hot favorite in this pace failed to win any games, although there were several minor strong players among his opponents.

Now how are these surprises to be explained? So far as Spielmann is concerned, it is well known that this sensitive artist is capable of top notch performances, but also that when he is not in form he can disappoint most grievously. One need only to recall his brilliant victory in the Semmering tournament of 1926 and then again his finishing last in the former Carlsbad tournament. The chess world, therefore, viewed him as a man of momentary successes, a prejudice which was wholly conceivable, for only those who have pursued his play in a long series of tournaments can arrive at a correct appraisal of his present unexpected series of victories.

He has had to conquer errors of a sporting nature as well as such as have to do with chess. As an artist he is impelled by an impetuous passion for combinations which, although they have earned him a number of brilliancy prizes, have also lost him many an important point in tournament scores. A tendency to explore all tactical details of his repertory of openings is characteristic of his play. He opened almost exclusively with his king’s pawn, which inevitably resulted in the clarification of the most important battleground of chess, viz.: the centre. While this may have injected an outward element of liveliness into the early stages of his game it nevertheless also resulted in a lessening of the more real tension.

Rudolf Spielmann

Spielmann’s principal sporting shortcoming as a chessmaster consisted in a slightly exaggerated good-naturedness which at times could not be distinguished from indifference. This was conspicuous in his drawn games in New York in 1927, where he tossed away winning prospects in decidedly superior positions.

He is also obsessed with idiosyncrasies with respect to some of his colleagues. For instance, up to a year ago he could not picture himself in the position of winning even a single game against Capablanca. His scores against Bogoljubow were also of an extremely moderate calibre.

Now what has remained of these shortcomings in tournament play? Spielmann will always remain an attacking player but he is now building up his attack on a fundamentally sound basis. In the place of a wild King’s Gambit or a speculative Viennese Opening, he has up to now adopted the more sedate Queen’s Pawn Opening in the Carlsbad tournament.

The Austrian also appears to be cured of his former attacks of “stage fright”. Last year in the Kissingen tournament he administered a decisive defeat to Capablanca. In the present Carlsbad tournament Spielmann apparently need not be in a hurry to accept draws because, according to the rules of play, a game may not be abandoned as undecided before the 45th move unless the tournament committee approves of a draw because the position has become hopelessly deadlocked.

In view of all this the prerequisites for another conspicuous success by Spielmann are available. This impression is strengthened when one considers the form in which some of his competitors have been playing, above all Capablanca. So far as the latter is concerned, it must be noted that his indifferent start is nothing unusual – one need only to recall Moscow in 1925 and New York in 1924. It will also not have a decisive bearing on the finish of the tournament because the Cuban master has been known to play the final spurt in a lively and energetic style. He will be among the first four in Carlsbad.

It is the quality of Capablanca’s games, however, that suggests comment. He shows a fighting spirit and a wealth of ideas all right, but one is compelled to note a certain tactical insecurity. In Moscow, for instance, Capablanca did not take pains to win against strong opponents, he rather contented himself with tedious, symmetrical variations of his Queen’s Gambit. In Carlsbad on the other hand he was determined to win against Rubinstein and Bogoljubow; he combined, even exposed himself to certain risks, and yet did not succeed. Against Thomas he even drifted into a very tight corner; Thomas might have won.

Bogoljubow’s play up to now makes a rather weak impression, which might also be said of Euwe. Vidmar, who is rector of the University of Laibach, has of late years been heavily engaged professionally, but hopes to show better form in the coming rounds. Nimzowitsch also has been playing unevenly. Alongside of several colorless draws he succeeded in winning his game against Bogoljubow, which must be counted as one of the most significant incidents of the tournament thus far.

This particular game is indicative of the modern conception of the beautiful in chess. It is distinguished by logical purity of structure, apparent in the visibility of means applied, complete unity in the profundity of a winning combination – elements which in an aesthetic sense impress the connoisseur much more than the outward effects of some of his former pyrotechnic finales. It is not improbable that we shall witness further games of this calibre in the course of the tournament.’

Article 3/6: New York Times, 21 August 1929, page 21:

‘CARLSBAD, Aug. 20. – The sixth and seventh rounds of the grandmasters’ chess tourney, which still is being played here, were not distinguished by any animation. This is accounted for on the ground that favorites are conserving their strength for the final spurt and also because they probably want to size up the various newcomers in this tournament.

With the exception of Rudolph [sic] Spielmann of Austria, whose chances of victory at this stage are becoming more evident, the play of Dr M. Vidmar of Yugoslavia deserves mention. His style may be characterized as “robust”, which also applies to his personality.

His conception of chess is both simple and sound and his very plain, yet highly effective style of play may be described as follows: In the opening he invariably seeks to obtain the initiative, that is, he aims to gain both time and space even at the cost of sacrifice. When he plays the black pieces, on the other hand, he is content to establish a safe defensive position, which he then endeavours to convert into a draw when opposed by players of equal strength.

The weaker opponents he seeks to entice into unsound sacrifice attacks. In this connection he reveals a concealed characteristic which not infrequently enables him to win. He has a certain good-natured rustic slyness characteristic of his Slovene countrymen. All told he is, perhaps, no lion in the realm of chess, but he is highly dangerous to those who permit themselves to be intimidated by his apparent harmlessness. He was the first player to take half a point from the leader.

The remaining masters in the tournament were chiefly concerned in maintaining their temporary standing without unduly exerting themselves. Thus the tournament proceeded up to the eighth round, after which it was transferred from the somewhat old and unattractive rooms of the Kurhaus to the modern Hotel Imperial, where the pleasure-seeking masters will have an opportunity to do a Boston or tango between moves or find diversion at roulette after a strenuous day’s work.

The effect of this electrified atmosphere on the more sensitive and artistic temperaments was instantaneous. All of the games in the eighth round, the first played in the Imperial Hotel, indicated the decisive results. Incidentally, this very exceptional development effectively refutes rumors of a “death through draws” which is alleged to threaten our art.

Among the victories scored on this day was one by Frank Marshall , the United States champion. It was scored after a brief but energetic light cavalry charge. This American combatant began the tournament with three successive defeats. He then pulled himself together and by superior playing managed to gather in five points.

Despite his talent, Marshall has a weakness which in the present stage of evolution in chess asserts itself most unfavorably in a sporting sense. He is primarily an artist by nature who seeks, without compulsion or restraint, to create a style of his own.

Nowadays every leading master must “look to the end”, for among the strong partners play almost invariably leads to simplification, and with the end-game in sight one always should have soundness of one’s pawn skeleton in mind. Only in such instances as, for example, in the game between Marshall and Sir George Thomas of England, when one of the players disregards the principles of sound opening strategy and fails to bring his king into safety, is a quick decision possible.

Spielmann, in contradistinction to Marshall, has adapted his style of play to the present-day demands and this explains his success. After the fashion of José Capablanca of Cuba, he now follows the tendency of avoiding complications, but compared to the Cuban grandmaster, with whom he shares the same technique of simplification, he has the advantage of a livelier imagination and greater accuracy. As in the Semmering tournament of 1926, Spielmann once again is the player who makes the fewest mistakes and who devours his victims with deadly security.’

Article 4/6: New York Times, 25 August 1929, pages 1 and 2 of the sports section:

‘CARLSBAD, Aug. 24. – After two-thirds of the grand masters’ chess tournament is over it can be said that the leading players are very cautious when opposing each other – about 90 per cent of their games have ended in a simple manner. The final standing, therefore, depends on the smartness with which they beat the so-called outsiders. It is very interesting to get the correct idea of the most prominent of these outsiders.

Regarding their prize-winning chances in this tournament the “minors” can be divided into two groups; those who no longer are able to do much and those who have not yet advanced very far. The senior master, Géza Maróczy of Hungary, and the Englishmen, Sir George Thomas and F.D. Yates, certainly belong to the former group and also – it is hoped, however, only for this one time – Dr S. Tartakower of France, a successful theorist and author on chess.

Maróczy, who about 20 years ago, after the death of the American genius, Pillsbury, was considered the most qualified rival of the “great Lasker”, then the world champion, is now a typical example of one who bears the inevitable sign of an older class bravely and with dignity. And he has no reason to envy the younger generation, for he shows no lack of talent, vigour and perceptivity, and only his will to win and great personal ambition, which is of the utmost importance for success in any contest, is no longer the same. But where national and not personal ambition is the question, he is marvelous.

At the international match in London in 1927 he appeared, after a long illness, as the head Hungarian player. Playing without any loss he incited his compatriots to such efforts that the palm of victory was allotted to the Hungarians.

Sir Thomas [sic] and Yates are typical representatives of the English school and style of chess, especially Yates. This school, founded by the great combination of players, Blackburne and Mason and the ingenious, although less profound, Bird, always lay greater stress on a thorough study of each tactical unit of a scheme than on judging the expediency of such a scheme.

That they had good results despite such a primitive conception of chess was due, especially by Blackburne, first to their extraordinary combinatorial talent and, second, to the fact that Steinitz’s epoch-making explanations of the principles of chess strategy were then only beginning to become popular.

This is quite different nowadays when every average champion is well equipped with strategical knowledge, especially those players who lay chief stress on the tactical moment in a match, and who must possess the most exact calculation and never-failing sharpness. For such types of players the signs of the older class are simply pernicious. Therefore it is not surprising that masters like Sir Thomas [sic] and Yates – who also in former times seldom detected the entire plan beyond a single move – are being driven to the background of the chess arena.

It is a different case with the highly talented Dr Tartakower. He is a victim of overproduction in chess, which also in our art gradually degrades the artist to a “tradesman”, and what is worse, he has lost his own style. It is incomprehensible that such a head can have such faltering ideas. Surely it is only a passing sign of fatigue. But for this tournament he no longer counts as a candidate for first prize.

Among the younger players, the Peruvian, E. Canal, who lives in Italy, and the Belgian champion, E. Colle, are to be mentioned in the first line. Each of them seeks a way to perfection by a path shown to him by his natural temperament. The South American, whose sparkling eyes and Indian profile attract attention, has presented himself in this tournament mainly as a cautious endgame player. On the other hand, Colle’s power of imagination commences when there is a possibility of attacking his opponent’s king. Canal lacks perseverance and Colle physical health.

I have suspended final judgment so far about Miss Vera Menchik of Russia, because the greatest caution and objectivity in criticism are necessary regarding anyone so extraordinary. However, after 15 rounds it is certain that she is an absolute exception in her sex. She is so highly talented for chess that with further work and experience at tournaments she will surely succeed in developing from her present stage of an average player into a high classed international champion.

She indisputably has attained her three points against the strong masters, but it is little known to the public that she has also attained superior positions against Euwe, Treybal, Colle and Dr Vidmar. She was beaten by Dr Vidmar only after a nine-hour match. It is the chess world’s duty to grant her every possibility for development.

Some of the “small players” were able to overthrow the tournament list in the last few days. Canal beat Spielmann, and Maróczy and Tartakower beat Bogoljubow. This defeat of Spielmann’s, however, was not decisive, for the Münchener was playing for first prize, but Bogoljubow is a candidate for the world’s championship.

His double defeat in this tournament is hardly retrievable. He probably will have to be content with moral success. However, Bogoljubow should not be deprecated. In a medium tournament at Dortmund in 1928 he attained only 50 per cent success, and afterward at Kissingen he was first, ahead of Capablanca and Spielmann. It would be a great mistake if in the next big match his opponent would permit himself to immoderate optimism.

Spielmann’s failure probably was due only to passing nervousness. He has sufficient chess abilities to remain at the head of this match. But it is admitted that Capablanca, who is on an equal standing with him after the 15th game, perhaps has greater chances morally. It is true the Cuban has succeeded – but not without some lucky incidents – to carry through his obvious intention to draw his games against dangerous opponents and “swallow all the small fish” by means of his superior technique.

Besides, Spielmann, Vidmar and Nimzowitsch are in a dangerous neighborhood. Nimzowitsch was lucky enough to win against Marshall when he was exposed to defeat.

The last third of the tournament promises, in regard to sport, to be the most exciting.’

Article 5/6: New York Times, 28 August 1929, pages 19 and 20:

‘CARLSBAD, Aug. 25. – After the failure of Rudolph [sic] Spielmann of Austria in the middle rounds of the chess tourney here, experts believed that José Capablanca of Cuba would be the winner. Therefore there was a great surprise when it became known, after 20 minutes of play against F. Sämisch, that the Cuban had lost, owing to a gross mistake on the ninth move, losing a major piece [sic] to the German master for only one pawn.

This game, which naturally lost all artistic value, was dragged by Capablanca to the 60th move. However, the inevitable at last happened. It is clear that a master of Capablanca’s class does not need to lose games in such a manner.

While such a mistake never has happened to masters of a less high class, such as A. Nimzowitsch of Denmark and Dr Vidmar of Yugoslavia, in their long careers, negligence with Capablanca is sporadical and nearly typical. Just remember the 1914 St Petersburg game with Tarrasch, the 1916 New York test with Chajes, the London match in 1922 with Morrison, the Moscow test of 1925 against Werlinsky, the 12th game at Buenos Aires in 1927 and the Kissingen match of the same year against Spielmann.

This short statistical outline, which easily could be continued, shows sufficiently that the former world’s champion lacks an important component of chess playing strength, namely an imperturbable attention which separates the player absolutely from the outer world. Therefore, with him, such mistakes as in the Sämisch game cannot be counted as a crash incident.

José Raúl Capablanca

Regarding the sporting point of view, however, Capablanca’s defeat has a positive value in that it prevents a new legend of his inviolability, which this tournament would have more than justified, being built up because he twice before was clearly exposed to defeat and only had to thank the carelessness of his opponents for his rescue.

Public attention thus has been called to Sämisch, who so far has had little luck at Carlsbad. Possibly big achievements may be expected of this agreeable German master, who won third prize in the 1923 tourney here, leaving a number of the bigger masters behind, and won two first prizes last year, losing not one of 42 games.

That the hopes placed in him in this tourney may not be realized is due – paradoxical as it sounds – according to the observation of the author of this article, to an excessive use of nicotine. Certainly a cigarette has a soothing effect for a moment. However, a player deep in thought and excited is easily apt to smoke too much, thus, in the first line, spoiling his memory and ruining his nerves and his power of resistance. Only when I rid myself of the passion for cigarettes did I attain enough confidence to win the world championship.

I believe, therefore, that if Sämisch is able to free himself of this habit he will enjoy a very good future in chess.

Naturally some of the masters showed signs of fatigue in the second half of the tournament, mainly Dr Max Euwe of Holland and Dr Vidmar. The latter does not seem as yet to have overcome the defeat by Professor A. Becker of Austria. He also seems not to have had sufficient experience in tournaments, otherwise he would know that defeat itself is not to be feared in a large tourney but rather its physical effects.

Another, besides the experienced tournament player Capablanca, proved that he is fully conversant with modern chess tactics and that is the Polish grand master, Akiba Rubinstein. All the admirers of this genius of chess will be pleased to hear this. Rubinstein’s career in chess has been original. After sharing first prize with Lasker in the great tournament at St Petersburg in 1909 and winning four first prizes in other large tournaments, all experts and Lasker, the world champion himself, considered Rubinstein qualified to be Lasker’s successor. His innovations in the opening theory and his masterly ability to find microscopic advantages in the final game have procured him a place of high honor in the chess hierarchy.

Then came the World War. In the post-War tournaments was Rubinstein quite changed. He no longer was the calm, methodical strategist who was able to turn the faults, almost imperceptible, of even the greatest players in his favor, but a man who apparently decided to replace his nerves, ruined during the years of the War, with a new temperament in his game. Hereby he obtained an exceedingly large number of brilliancy prizes – at the Teplitz tournament he won five such prizes – but this system did not prove successful for any length of time.

In 1924 and 1925 he suffered heavy defeats and had to change his system again. Luckily he has succeeded. He has realized the necessity of balancing the modern theories of chess with his special talent. That this is the correct point of view is shown in this tournament. The “second chess youth” which Rubinstein is surely approaching will find him, according to his talent, a very great man.

As this is being written there still are three rounds to be played. A finish seldom has been so exciting as this one. Spielmann still has to play against Nimzowitsch, and Capablanca has such heavy opposition as Dr Vidmar and Maróczy, while Nimzowitsch still has to encounter Tartakower and Maróczy.

The difference of a half a point between the three first-named is almost zero. Capablanca seems unmoved by his defeat, Nimzowitsch, although somewhat agitated, is encouraged by his success, and Spielmann, even if somewhat fatigued, is incited by a decided “will to win” which promises a lot.’

Article 6/6, New York Times, 30 August 1929, pages 13 and 14:

‘CARLSBAD, Aug. 29. – The fourth international grand masters’ chess tournament at Carlsbad resulted in an exciting finish, Aaron Nimzowitsch being the man of the day. Other winners of prizes lent significance to the tournament.

That was a finish. Every day [sic] of the last round was a surprise, and the biggest was another victory for Rudolf Spielmann over José R. Capablanca.

This game former champion was defeated by Spielmann’s heavy direction of play. From the first to the last move he was unable to do anything against the attack. It was all the harder for the Cuban to lose this encounter as his other competitor in the finishing phase showed an extraordinary playing disposition.

Spielmann took the lead at the beginning and kept it during the first half of the tournament. Capablanca gained ground according to his manner, slowly and apparently surely. Nimzowitsch played his speed and had a very narrow victory. Nimzowitsch’s first prize, the first success of his chess career, was the only surprise from a sporting point of view. The widest circles expected Capablanca to win although he often disappointed his adherents last year. From a point of view of quality, there was only one opinion possible about Nimzowitsch’s achievement at Carlsbad: it was by far most significant of all.

Right at the beginning of the tournament, he pleased his friends with a genuine game against Bogoljubow, who was a dangerous opponent. Then he showed some uncertainty which caused some dull draws and the sole loss of one game against Yates.

Driven back to the middle tournament list, he patiently waited for something to occur to give him back his self-confidence and incite him to a new maximum of achievement. He actually received such incitement from his miraculous rescue in the game with Dr Euwe. It was in the ninth round when, in promising position, the Dutch precedent player permitted himself to be checkmated by a gross trap by Nimzowitsch, who suddenly advanced to the first line, where he remained.

Nevertheless, four rounds before the finish, his prospects of attaining first prize were still poor. Standing one half point behind the leaders, he still had to play against the four big guns, Vidmar, Spielmann, Maróczy and Tartakower.

Not only was it a fact that he won three and one-half encounters of these four games, but he did so in emphatic and deep style, worthy of a first prize winner of such a significant tournament.

If in addition one considers what Nimzowitsch attained against other winners, by far the best result – four victories, three draws – then his success must be of higher value than the advance points, which at first glance only appear small.

In a preliminary article of the Carlsbad tournament we referred to Nimzowitsch as an advocate of a real artistic line. This victory of the mediating explorer of our art will gladly welcome all those who see more than entertainment or sporting record in chess.

In America he became known as a sensible player by participation with six [sic] champions in a tournament in New York in 1927, especially by his impressive start. However, one is only able to form a correct opinion of the chess artist and philosopher, Nimzowitsch, if he is acquainted with his books. His last book is especially interesting. Therein he illustrates by numerous games his strategy which he calls “system”, and does this in such original manner that the reader is led to a new kind of reflection on chess without noticing it.

Aron Nimzowitsch

His great chess knowledge certainly was a preliminary condition to his victory, but undoubtedly his fine physiological treatment of an opponent also contributed to the victory. That especially was noticeable in games against Spielmann and Tartakower. Knowing Spielmann would not be content with a draw, he drew him into a prolix variant exchange and thereby in the end obtained a very small but undeniable advance.

He noticed that the grand master Tartakower was so fatigued that he had only capable and brilliant ideas, but could not stand through a game for hours. Therefore, he started a lengthy rochade attack and Tartakower actually collapsed in the sixth hour of play after a splendid defense at the beginning.

According to the course of play following the allotments, Spielmann deserved a high prize on account of his splendid achievement in the first half of the tournament and Capablanca’s defeat.

But Spielmann’s nerves forsook him at important moments – in the game with Rubinstein and in the final game with Mattison, in which he already was on the winning point.

Capablanca delivered some games which owing to a symmetrical style had an aesthetic effect. Even if there is any question of his indisputable superiority over precedent players, he nevertheless is one of the foremost and likely to remain so for a long time.

We told about Rubinstein’s significant success in the last article. As to Vidmar and Euwe, they hardly fulfilled the hopes their adherents had placed in them. Professor Becker passed his first international test successfully.

Bogoljubow’s last prize, of course, corresponds in no degree to his real playing strength. We know from example of the talented grandmaster Schlechter that deficient shape in any master may be only passing. Soon after his failure in the Petersburg tournament in 1909 he was able to draw a game with the giant Lasker. Bogoljubow is sure to show quite a different force in the forthcoming championship match.

The Carlsbad tournament, in which alert play and full ideas were shown, is of greater value to chess than merely the sport of comparison of results. It has shown that chess, even in its present shape, is exceedingly far from destruction owing to drawn games and unnecessary reforms which some desire to force upon the play.

Three cheers for the future, everlasting young and old in chess!’

Left to right: Aron Nimzowitsch, Victor Tietz, Alexander Alekhine (Carlsbad, 1929)

Note: These texts were originally reproduced by us in C.N.s 1274 and 1319, in 1986-87.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.