Edward Winter

From Chess Miniatures & Caricatures by Jovan Prokopljević (1999)

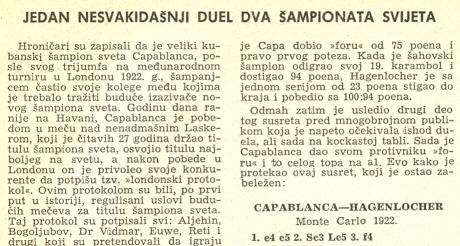

An interesting article appears in the October 1982 issue of the Yugoslav magazine Šahovski Glasnik (pages 363-364).

We learn that after the London Rules for world championship challenges had been agreed in 1922, Capablanca went to Monte Carlo ‘to relax’. Also there at that time was Erich Hagenlocher, a German from Stuttgart who in the 1920s was the unchallenged billiards champion of all cafés and casinos in Europe. Since each of the champions could play the other’s game, somebody had the idea of a contest between them. Billiards came first, with a match for the first to reach 100 ‘Karambols’ (forgive our lack of billiards terminology) with Capa given a start of 75 and the right to play first. The Cuban in fact reached 94, but then Hagenlocher struck back with a run of 23, thereby gaining victory by 100 to 94.

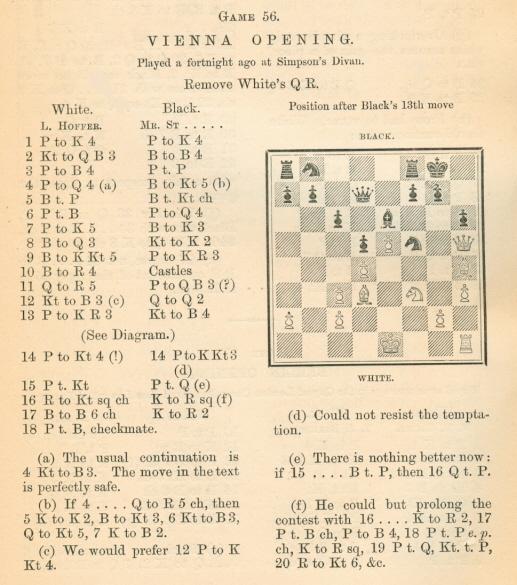

So on to chess. One game was played, with Capa giving the odds of his queen’s rook: J.R. Capablanca- E. Hagenlocher, Monte Carlo, 1922. Remove White’s queen’s rook. 1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Bc5 3 f4 exf4 4 d4 Bb4 5 Bxf4 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 d5 7 e5 Be6 8 Bd3 Ne7 9 Bg5 h6 10 Bh4 O-O 11 Qh5 c6 12 Nf3 Qd7 13 h3 Nf5 14 g4 g6 (Now comes an appealing finish.) 15 gxf5 gxh5 16 Rg1+ Kh8 17 Bf6+ Kh7 18 fxe6 mate.

And so it was that the first, and no doubt last, chess-billiards double-bill ended in a 1-1 draw.

(318)

We hasten to invite readers to draw a thick red line across C.N. 318. It now appears that Capablanca never played any such chess-billiards match.

Gunter Müller (Bremen, Germany) has sent us a considerable amount of information, based on the writings of Hans Klüver, that indicates that the Capablanca-Hagenlocher episode is pure fiction. Apparently Die Welt published the story as a joke towards the end of the 1950s. As often happens, a subsequent correction/confession was ignored and the account was republished elsewhere in German sources (Mr Klüver gives chapter and verse). Šahovski Glasnik, our source, may have picked it up from one of the German versions.

We learn that the original version of the hoax had it that the game was played on 31 December 1922. There are some discrepancies over the billiards, with the German versions saying that the run of 23 that Hagenlocher achieved brought him up to 92, and that it was Capa who won, by 100-92. Information on Hagenlocher would be welcomed – did he exist? The chess game itself, our German colleagues tell us, was actually played by Hoffer at the turn of the century. Presumably it was an off-hand game – can anyone identify the occasion?

Such hoaxes in chess history must be very rare.

(368)

David Hooper (Bridport, England) writes:

‘After giving six simuls in England in October 1922, Capa left for the USA, arriving there on 12 November 1922, staying about five weeks, and then going home to Cuba for Christmas. Capa often left the USA to arrive in Cuba on Christmas Eve. He could hardly have been in Monte Carlo on 31 December.

If people are going to fake things they should at least get known facts correct, so that the event is plausible. Contrary to your view, I am of the opinion that many games are faked.’

In defence of our own original publication of the hoax, may we point out that our source, the Yugoslav magazine, made no mention of 31 December 1922, but merely stated vaguely that Capa went to Monte Carlo after the London tournament – which was quite plausible.

W.R. Hartston (Cambridge, England) sends the following:

‘There’s an interesting postscript to your Nos. 318 and 368 which makes it all the sadder that the story wasn’t authentic. During the Phillips & Drew tournament in London, 1982, attempts were made to arrange a snooker/chess match between Karpov and Steve Davis. Only the fact that no date could be found on which both gentlemen were free prevented this from taking place. Each is very keen on the other man’s game, and serious efforts were made to arrange a meeting (mainly for publicity purposes, of course).’

(440)

So far Šahovski Glasnik has failed to print a retraction of the Monte Carlo chess/billiards hoax. Why?

(491)

Europe Echecs has also published the Capablanca billiards hoax, in its April [1983] issue (page 15). No doubt a correction is imminent.

(514)

It was not.

Ken Whyld (Caistor, England) has found the Capablanca-‘Hagenlocher’ story and game on page 66 of the December 1951 Deutsche Schachzeitung, the source being given as H. Klüver’s Die Welt column. This means that our correspondent Gunter Müller was wrong in C.N. 368 to speak of ‘the end of the 1950s’. The next stage is to find out exactly when Die Welt published the hoax, and when, if ever, it owned up. In late 1951, presumably. Can one of our German readers do some hunting?

(1425)

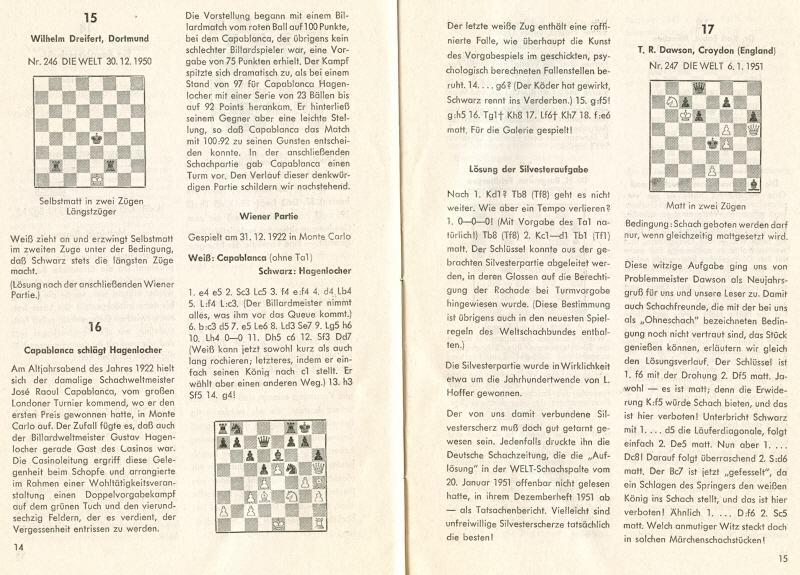

Hans-Georg Kleinhenz (Stolberg, Germany) answers C.N. 1425. A collection of Hans Klüver’s columns was published under the title Faschingsschach der Welt (Siegfried Engelhardt Verlag, Berlin-Frohnau, 1963). This book (pages 14-15) indicates that the original hoax (with the game-score given in C.N. 318) appeared in Die Welt on 30 December 1950. A retraction was published in Klüver’s column of 20 January 1951.

There remain a couple of loose ends:

a) Klüver states that the game was actually won by Hoffer at the turn of the century (see C.N. 368). Can anyone find its original publication?

b) Did the billiards world have a Hagenlocher? (Incidentally, our initial source of the story, Šahovski Glasnik, said his forename was Erich. We note that Klüver gives Gustav.)

(1502)

Jack O’Keefe (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) writes:

‘There are numerous references to Hagenlacher in the New York Times of 1925-1927. The name is always spelled “Hagenlacher”, though the first name is occasionally given as “Eric” rather than the correct “Erich”.

Some references are: 1926: 13 March, page 13:3, for a summary of Hagenlacher’s career up to that point; 1925: 4 December, page 28, where the headlines of adjoining columns are “Hagenlacher Balks at Billiard Deal” and “Bogoljubow Wins Again at Moscow”; and 1927: 23 September, page 25:2, where one can read about Hagenlacher’s exhibition match versus Willie Hoppe, then turn to nearby pages for accounts of Tunney-Dempsey or Capablanca-Alekhine (Match: Game 3).

According to the New York Times, Erich Hagenlacher was born in Stuttgart, Germany, on 25 July 1895. He won the world championship at 18.2 balkline billiards by defeating Jake Schaefer in March 1926 and lost the title to Willie Hoppe in January 1927.’

Congratulations to Jack O’Keefe, who has discovered that the fake Capablanca-Hagenlacher game was Hoffer-St..... ‘played a fortnight ago at Simpson’s Divan’ (Chess Monthly, May 1880, page 276). Ellis’ Chess Sparks (page 86) gives the date as April 1880.

Chess Monthly, May 1880, page 276

Slowly but surely all the key facts about this matter now seem to have come out.

(1837)

As noted in C.N. 3939, on pages 273-274 of The Batsford Book of Chess Records (London, 2005) Yakov Damsky related the Capablanca chess/billiards yarn, unaware that the whole thing was a hoax. Capablanca’s opponent was named as Hagenlohen.

From an historical article on the Queen’s Gambit on pages 453-457 of the December 1905 BCM:

‘During the decade 1830 to 1840 it was considered mean and somewhat analogous to “potting” one’s opponent at billiards to adopt the Queen’s Gambit.’

Source: Brentano’s Chess Monthly, August 1881, page 170

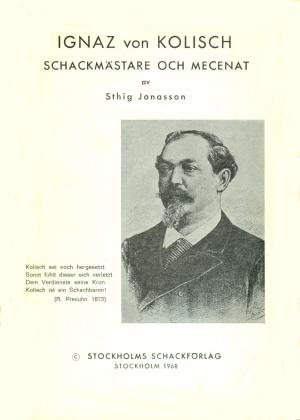

A well-known chess-billiards anecdote may be recalled, concerning a person who claimed to have beaten leading exponents of chess and billiards, albeit defeating the chess expert at billiards and the billiards expert at chess. Virtually mirthless, the story nonetheless occupied much of the section on Kolisch on pages 40-44 of Chess Life-Pictures by G.A. MacDonnell (London, 1883). The book stated that in Marseilles in 1867 M. Belvoir claimed victory over Berger and Kolisch at chess and billiards respectively.

On pages 220-221 of the July 1889 Deutsche Schachzeitung the tale received 38 lines, Marseilles becoming Paris. The French capital also featured in the lengthy rendition on page 192 of Capablanca-Magazine, 15 October 1912. The following year, a version appeared with Steinitz and Roberts representing chess and billiards respectively. The person who defeated them was named as George E. Walton, the President of the Birmingham Chess Club. See ‘Billiards and Chess’ by Robert J. Buckley on page 90 of the April 1913 American Chess Bulletin.

The yarn is, though, most commonly associated with Kolisch, and it appears on page 37 of Ignaz von Kolisch schackmästare och mecenat by Sthig Jonasson (Stockholm, 1968).

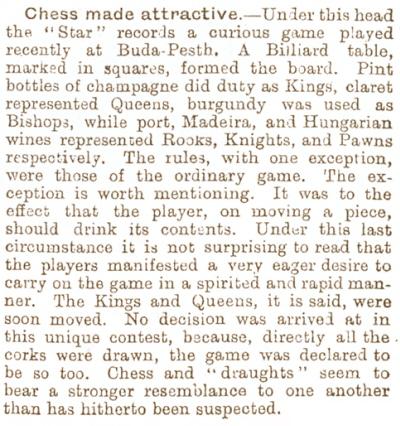

Three further references to ninenteenth-century items on chess and billiards:

(6415)

From page 173 of All Things Considered by Bernard Levin (London, 1988) comes another (‘once’) example of how tinkering with chess can make an ‘intellectual’ writer seem anything but:

‘Fischer is not known to have done, said or thought anything at all other than about matters pertaining to chess, and once, when he gave up chess temporarily, he did nothing but play billiards for a couple of years.’

(8068)

From page 86 of CHESS, January 1940:

(9651)

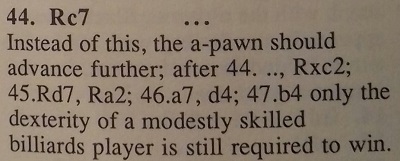

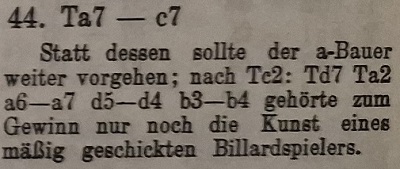

João Pedro S. Mendonça Correia (Lisbon) draws attention to this annotation on page 217 of the Caissa Editions translation (Yorklyn, 1993) of Tarrasch’s book on St Petersburg, 1914 and wonders whether any personal acrimony underlies the reference to billiards:

From the original German edition (page 151):

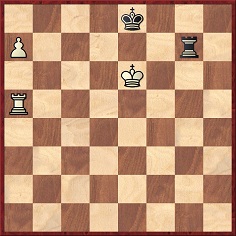

The game was Capablanca v Marshall in round four of the final section: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 d6 4 Nf3 Nxe4 5 Qe2 Qe7 6 d3 Nf6 7 Bg5 Be6 8 Nc3 h6 9 Bxf6 Qxf6 10 d4 Be7 11 Qb5+ Nd7 12 Bd3 g5 13 h3 O-O 14 Qxb7 Rab8 15 Qe4 Qg7 16 b3 c5 17 O-O cxd4 18 Nd5 Bd8 19 Bc4 Nc5 20 Qxd4 Qxd4 21 Nxd4 Bxd5 22 Bxd5 Bf6 23 Rad1 Bxd4 24 Rxd4 Kg7 25 Bc4 Rb6 26 Re1 Kf6 27 f4 Ne6 28 fxg5+ hxg5 29 Rf1+ Ke7 30 Rg4 Rg8 31 Rf5 Rc6 32 h4 Rgc8 33 hxg5 Rc5 34 Bxe6 fxe6 35 Rxc5 Rxc5 36 g6 Kf8 37 Rc4 Ra5 38 a4 Kg7 39 Rc6 Rd5 40 Rc7+ Kxg6 41 Rxa7 Rd1+ 42 Kh2 d5 43 a5 Rc1 44 Rc7 Ra1 45 b4 Ra4 46 c3 d4 47 Rc6 dxc3 48 Rxc3 Rxb4 49 Ra3 Rb7 50 a6 Ra7 51 Ra5 Kf6 52 g4 Ke7 53 Kg3 Kd6 54 Kf4 Kc7 55 Ke5 Kd7 56 g5 Ke7 57 g6 Kf8 58 Kxe6 Ke8 59 g7 Rxg7 60 a7 Rg6+ 61 Kf5 Resigns.

Tarrasch also criticized 46 c3, appending a question mark.

Below is the position after White’s penultimate move, 60 a7:

Tarrasch called Marshall’s 60...Rg6+ a Racheschach. It is not a ‘spite check’ strictu sensu, given that two of the three possible king moves by White lose.

(11997)

In connection with Capablanca’s simultaneous display in Hastings on 23 August 1919, an unsigned interview was published on page 4 of the Birmingham Evening Despatch two days later which included this exchange:

‘“Do you ever play billiards?”

“I have played several games”, said Capablanca, adding with a quizzical little smile, “but I have a tendency to send the ball across the edge of the table, and I have made some little rips, too, in the cloth. For this reason I am not exactly a welcome visitor to a billiard saloon.”’

The accuracy of details in such interviews is not to be taken for granted.

(12072)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.