Edward Winter

Chessathon: A term for tournaments registered by the USCF on 17 July 1996 with an application stating that it was first used on 1 April 1992.

Chessay: ‘Captain Evans ... inventor of the marvellous gambit which made this chessay possible.’ CHESS, 14 January 1939, page 181. The terms was also used in the subtitle of the book Not Only Chess, ‘A Selection of Chessays’ by G. Abrahams (London, 1974).

Chesscape: ‘As a result of the upheaval in Europe, many minor European masters and near-masters are now resident in England, lending colour and variety to the British chesscape.’ Chess Springbok by Wolfgang Heidenfeld (Cape Town, 1955), page 9.

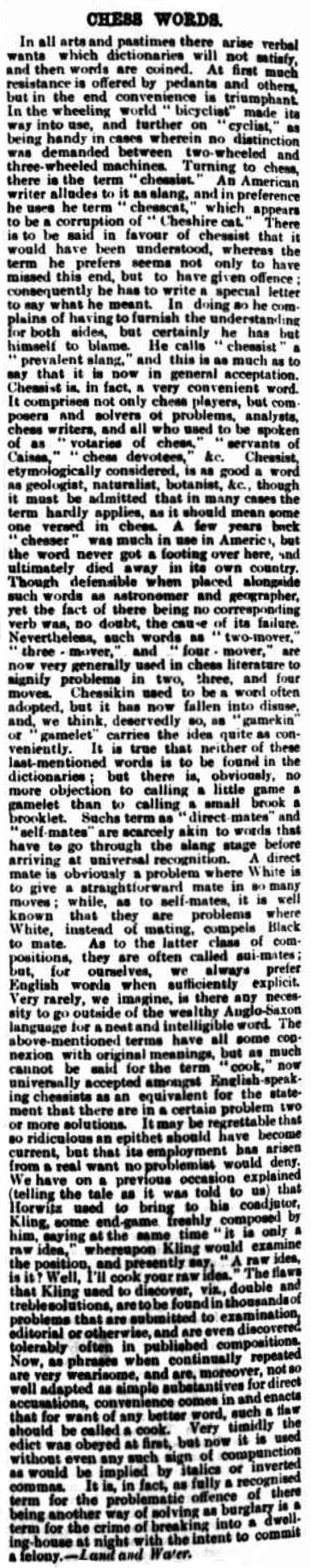

Chesscat: ‘Turning to chess, there is the term “chessist”. An American writer alludes to it as slang, and in preference he uses the term “chesscat”, which appears to be a corruption of “Cheshire cat”.’ Land and Water (date?) Reproduced on page 2 of the Australasian Supplement, 21 February 1885. See C.N. 10493.

Chesscellaneous: Chapter heading on pages viii and page 43 of The Chess Beat by L. Evans (Oxford, 1982).

Chessdom: ‘The British Chess Association Problem Tourney Committee bids fair to be the best abused body in Chessdom.’ City of London Chess Magazine, October 1874, page 209.

Chesser: ‘English chessers, to use the American word, for which we seem to have no good substitute, … ought certainly to subscribe to this capital monthly.’ City of London Chess Magazine, May 1875, page 105. See also the short poem (1878) in C.N. 7777.

From page 334 of the Maryland Chess Review, 1874:

‘We implore our Charleston friends not to allow another “Alligator” to attack Mr Orchard, as, in that case, we might easily be converted into a “Handsaw”, which would not be very appropriate, even if we have a brother Chesser who is a “Carpenter”.’

Chessercize: In 1991 Bruce Pandolfini wrote two books, Chessercizes and More Chessercizes.

Chessiad: Comic Tales and Lyrical Fancies; Including The Chessiad, A Mock Heroic, in Five Cantos and the Wreath of Love, in Four Cantos by C. Dibdin the Younger (London, 1825).

Chessian: ‘Another correspondent stoutly maintains the availability of scacchic – others mention chessical, chessian, zatrikial and exchequerian.’ Chess Monthly, November 1859, page 360. See C.N. 8999.

Chessiana: heading on the first (unnumbered) page of text in unit three of Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play by W.E. Napier (New York, 1935).

Chessic: ‘MY intent in this Poem was, through the medium of a burlesque battle, to convey to the learner, in an amusing manner, the first principles of the GAME OF CHESS, according to Phillidor [sic]; the value of the PIECES being signified by the rank of the chiefs, and the nature of the moves and operations of the chessmen represented by the modes of march, evolutions, and actions of the chessic warriors.’ Page 115 of Comic Tales and Lyrical Fancies; Including The Chessiad, A Mock Heroic, in Five Cantos and the Wreath of Love, in Four Cantos by C. Dibdin the Younger (London, 1825).

Chessical: ‘Away with all flimsy excuses; they

are not chessical.’ G. Walker, Liverpool Mercury,

24 January 1840, page 27. See C.N. 7776. The later term

‘chessical gradgrinds’ (coined by A.F. Mackenzie) was noted in

C.N. 5347.

Chessically: ‘Yes, and where would these very upstart, opinionated scribblers themselves have been (chessically) but for this very Mr Staunton?’ New York Clipper, 9 October 1858, page 196 (column by Miron J. Hazeltine). See C.N. 9506 (as well as C.N. 8999).

Chessie: ‘... his many chessie friends.’ Chess Weekly, 17 July 1909, page 60.

Chessikin: ‘... about two years ago this Chess-i-kin cropped up in the Illustrated London News ...’ Westminster Papers, 1 May 1873, page 2, in a letter from H.A. Kennedy written in Reading on 7 April 1873.

‘A correspondent at Delft has favoured us with another “Chessikin”, as Captain Kennedy has happily named those brief and brilliant little encounters.’ Westminster Papers, 2 June 1873, page 26.

Chessing: ‘… such terms as chessy, chessist, chessing and caïssic are revolting hybrids. Chess jargon and clichés can be bad enough without resorting to such vulgarisms.’ D.J. Morgan on page 334 of the December 1953 BCM.

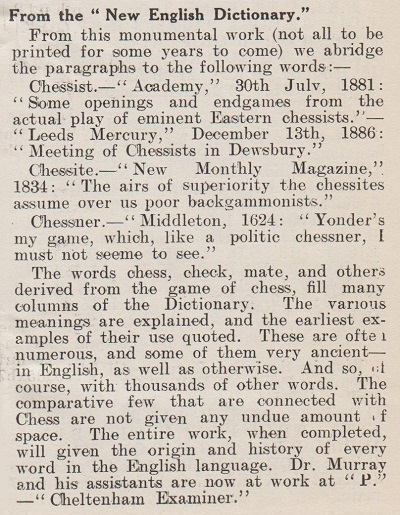

Chessist: ‘A Boston paper calls an editor a “writist”, a New Hampshire paper speaks of a “hair cuttist” and a Pennsylvania paper styles Paul Morphy as “a chessist”’. Brooklyn Eagle, 5 October 1868, page 1.

Chessite: ‘The airs of superiority the chessites assume over us poor backgammonists.’ New Monthly Magazine, 1834.

Chesslet: ‘Chesslets’ was the title of brief compilations of quotes in Lasker’s Chess Magazine, December 1904, page 81, and January 1905, page 126. J. Schumer published a small book entitled Chesslets in 1928.

Chessling: ‘If only a chessling, beware how you talk chess (about Philidor, Staunton and gambits, for instance) before anyone who understands these matters.’ Page 32 of A Popular Introduction to the Study and Practice of Chess by S.S. Boden (London, 1851), a book published anonymously.

Chesslorn: ‘Advice for the Chesslorn’ was the heading of a section in a column by Eliot Hearst on pages 38-39 of the February 1963 Chess Life.

Chessmanity: ‘He will have some claim to be regarded as a benefactor to “chessmanity”.’ F.P. Wildman, BCM, December 1901, page 497.

Chessner: ‘Yonder’s my game, which, like a politic chessner, I must not seeme to see.’ T. Middleton’s Game at Chesse (1624).

Chessnicdote: Chessnicdotes I and Chessnicdotes II: titles of books by G. Koltanowski (1978 and 1981).

Chesso-mania: ‘In a very short time, however, I myself became thoroughly inoculated with Chesso-mania ...’ H.A. Kennedy on page 123 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1851.

Chessophile: ‘[Ray] Kennedy himself has been a chessophile since the age of nine ...’ Ralph P. Davidson, Time, 31 July 1972, page 2.

Chessophobe: ‘The base calumny industriously spread by “chessophobes” (to coin a word) should be silent in face of these facts.’ P.H. Williams, American Chess Bulletin, February 1911, page 26.

Chessophrenetic: ‘(nonce term) a chess fanatic.’ Page 65 of An illustrated Dictionary of Chess by Edward R. Brace (1977).

Chessophrenia: Page 289 of Chess Review, October 1953 (letter from William Benedetti, Las Vegas).

Chessophrenics: ‘I would punish them for all eternity with the denomination of “Chessophrenics”’. Page 289 of Chess Review, October 1953 (letter from William Benedetti, Las Vegas).

Chess-o-rama: ‘Lawrence H. Nolte, a 63-year-old Canadian-born inventor, of Lebanon, Pa., won a gold medal at the International Patent Licensing Exhibition in New York for “Chess-o-rama” in April. This game allows up to eight persons to play four interlocking chess games at a time, on a four-foot square board representing four oceans and five major land areas ...’ CHESS, June 1973, page 271.

Chessorama: Chessorama by Nigel Davies was due to appear in 2001, from B.T. Batsford Ltd., but the book was never published.

Chesspearean: ‘The brutal plot of this Chesspearean tragedy culminates in banishment of the lady.’ Page 40 of The Personality of Chess by I.A. Horowitz and P.L. Rothenberg (New York, 1963).

Chesspool: ‘... that monthly chesspool’. Description of The Westminster Papers in the August 1888 International Chess Magazine, page 236.

Chess-smith: ‘A chess-smith, too, must go into the forge and strike the iron on its white-hot places.’ W.H.K. Pollock, Baltimore Sunday News, 23 September 1893. See C.N. 10484.

Chesstapo: Title of a poem (a Mikado parody) by F.J. Whitmarsh on page 28 of the February 1944 BCM.

Chess-ty: ‘The champion’s “chess-ty” physical make-up is not that of the popular conception of a chess-player.’ C. Sherwood, writing about Alekhine in the Los Angeles Times. The item was quoted on page 96 of the May-June 1929 American Chess Bulletin.

Chessy: ‘Z Z – A neat game but too meagre for

publication. Black’s last move of queen to R 3 is very

chessy.’ Page 2 of Bell’s Life in London, 29 March

1840. See too C.N.s 6807 and 6782.

Acknowledgements: for the 1874 ‘chesser’ quote, to Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA); for the ‘chessiad’, ‘chessic’ and ‘chessophile’ quotes, to Mark McCullagh (Belfast, Northern Ireland); for the ‘chessikin’ quote, to Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany); for the ‘chessist’ quote, to Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina); for the ‘chessical’, ‘chessically’, ‘chess-i-kin’ and ‘chessy’ quotes, as well as C.N. 8999, to Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada); for the ‘chesso-mania’, ‘chessophrenia’ and ‘chessophrenics’ quotes, to Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore). As shown on pages 235-237 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, many of the entries were initially given by us in Kingpin, and it was the Editor of that magazine, Jonathan Manley, who first raised the topic with us, in 1997.

A few chessy words were reproduced from the Cheltenham Examiner on page 207 of the Chess Amateur, April 1908:

(10197)

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) notes this item on page 2 of the Australasian Supplement, 21 February 1885:

(10493)

Jean Fontaine (Montreal, Canada) reports that the following chessy words all come from Japanese Chess (Shō-ngi): the Science and Art of War or Struggle Philosophically Treated; Chinese Chess (Chong-kie) and I-go by Chō-Yō (New York, 1905), many of them appearing several times:

Chessologic: ‘The habit of patience and conformity with orders and observance of the rules of refined etiquette is absolutely cultivated by chessologic practice.’ Page 27.

Chessological: ‘The Chinese nomenclature, from a chessological view point, clearly and wisely depicts both concretely and esoterically the general aspect of the most abstract and majestic of all departments of knowledge, which is power.’ Page 30.

Chessologically: ‘The question, whether or not chess, however the greatest of intellectual games, might be too much of a strain on the mind, could be chessologically answered in regard to whether or how far it may become a recreation or an excessive and hurtful exertion […].’ Page 23.

Chessologician: ‘The Japanese are born chessologicians!’ Page 185.

Chessologics: ‘These are perfectly and beautifully displayed in chess, especially in Japanese chess, decidedly hundred times or ad infinitum more than in any other chess or branches of Chessologics […].’ Page 74.

Chessologist: ‘They have been the profoundest chessologists and not mere chess players who have adopted these highest conceptions of Mathematics, Physics, Philosophy and Poetry for chessworks.’ Page 66.

Chessology: ‘Chessology, in its largest sense, treats of the principles of the science of human struggles conceivable and symbolized in the shortest, smallest and least possible time, space and force and played as the highest and most intellectual game to develop and train the Mind, by virtue of amusement accompanied with competition […].’ Page 15.

Chessonym: ‘Chessonym or Chessological Figure is a symbolic name or an algebraic sign put on a Koma, chess-piece, or the board itself, as an index of the function of an element or groups of elements in struggles; hence Chessonymy, the method of using the Figure for brevity’s sake, hence chessonymous.’ Page 48.

Chessonymic: ‘Thus any physical and intellectual and speculative elements and some new resources […] are figuratively expressed in Chessonymic Symbols by the Mochingoma.’ Page 93.

Chessonymous: ‘Every Koma piece in its secondary meaning has much wider scope than an ordinary player would give it the power or value, and in fact, all of the names of the pieces, Koma, should include secondary meaning expressed in Chessonymous Symbolic Figures.’ Page 88. See also the Chessonym quote above.

Chessonymously: ‘“Queening a pawn” would be a ridiculous performance if we do not understand it chessonymously by esoteric connotation of the meaning of trans-modifications of force or vitality […].’ Page 189.

Chessonymy: ‘Chessonymy shows that Koma is also written as […], literally, Ko, game [on cross-lined board] and ma, horse, a Figure of Speech for hopping and galloping on the part of horses in significance of movements of pieces across the lines or sections over the chessboard (war or struggle game field), and it means “chessmen”[…].’ Page 54. See also the Chessonym quote above.

Unchessologically: ‘[…] a persistence in taking odds […] takes the game out of its proper grooves, and tends to produce positions not naturally or unchessologically arising in the ordinary course of the game, as developed from the recognized openings.’ Page 26.

(10510)

Latest update: 5 April 2025.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.