Edward Winter

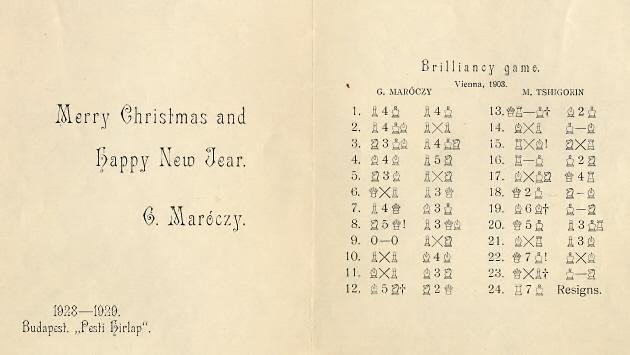

C.N. 6922 quoted an item about Géza Maróczy on page 26 of the February 1929 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Only recently the famous Hungarian sent out as a Christmas greeting card to his wide circle of friends the score of the Muzio Gambit which he won from Chigorin in the Vienna Gambit tournament of 1903.’

Subsequently, David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA) submitted a copy of the card, for presentation in C.N. 6928:

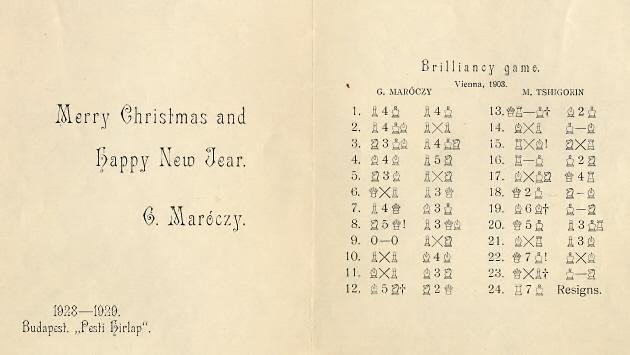

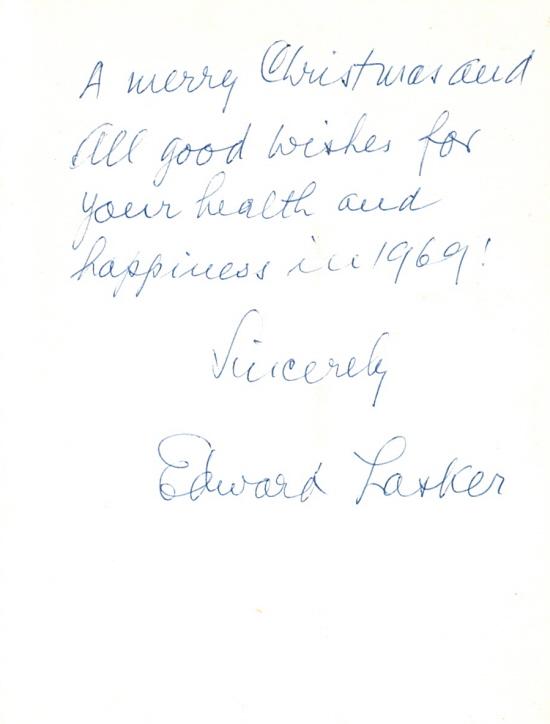

From our collection comes this card sent by Edward Lasker to the Morphy authority David Lawson:

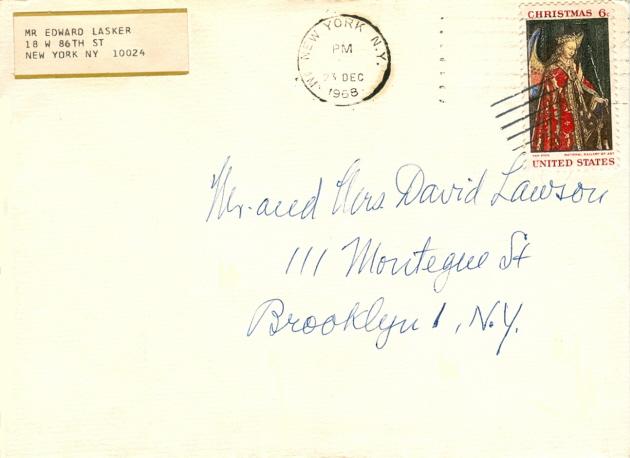

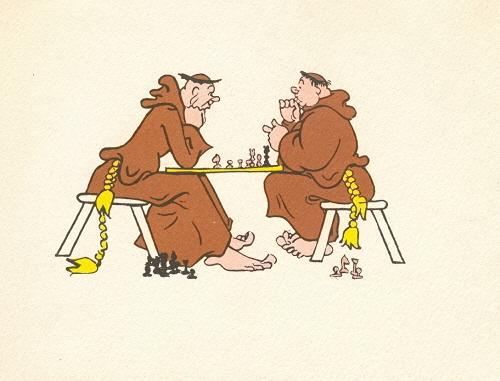

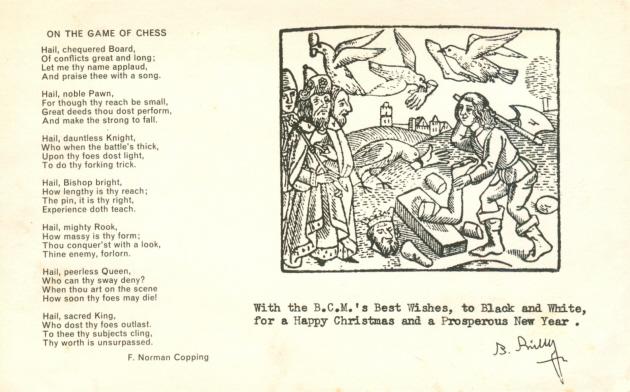

Below is a rare example of Christmas card with an un-Christmassy chess theme:

Next, two cards signed by Brian Reilly, the longstanding editor of the BCM:

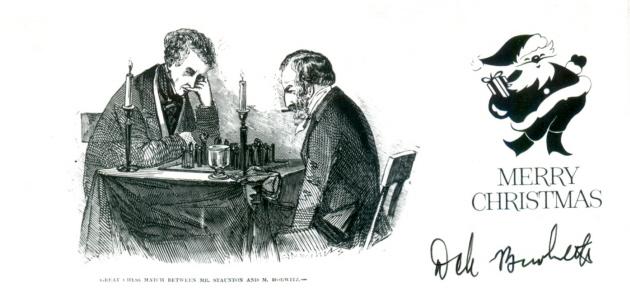

Our collection also includes a card depicting Howard Staunton in play against Bernhard Horwitz, issued and signed by Dale Brandreth:

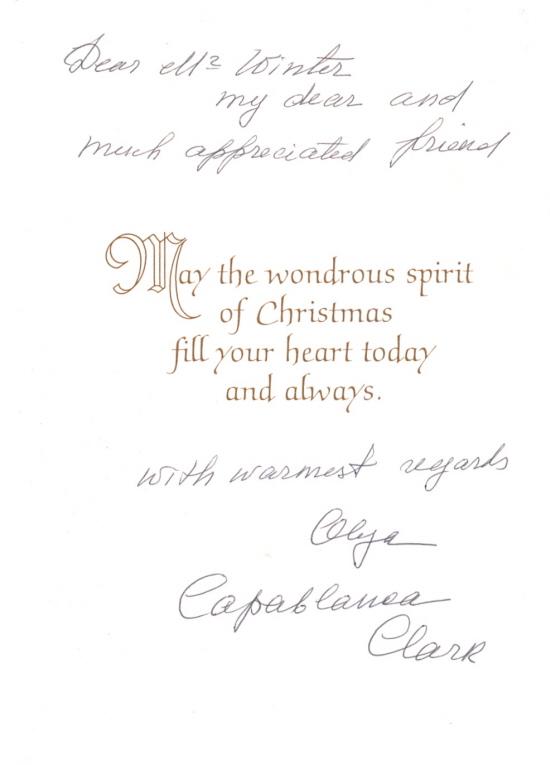

Finally, we show two of the cards we received from Olga Capablanca Clark and Irving Chernev:

This article originally appeared at ChessBase.com.

The following article is reproduced from pages 43-44 of our publication Chess Characters, volume two by G.H. Diggle (Geneva, 1987), having originally appeared in the Christmas 1986 issue of Newsflash. Known as the ‘Badmaster’, Diggle, a quintessentially English writer, was aged 84 at the time.

‘The Badmaster, though now retired from chess polemics, has received a kind invitation from the Editor to send Acrimonious Greetings for Christmas 1986. In response to numerous anxious enquiries from pseudonymous admirers (such as In Zugzwang, Three Pawns Down and Just Fools-mated) the BM is pleased to report that, like Captain Corcoran, “he is in reasonable health” and happy to sit reading Newsflash each week and watching the Chess World go (or rather whizz) by with momentous British triumphs and weekend tournaments springing up, in and out of season.

As one of these (Brighton, 1986) landed right on his doorstep, the BM actually tottered down to “The Old Ship” and entered for one of the side-shows. As his last appearance in a South Coast Tournament occurred 47 years ago, it was like leaping a two-generation gap and landing on a new chess planet. The BM had innocently expected to encounter grave adversaries in sober attire who had procured respectable weekend apartments on the Sea Front (Visitors are requested not to play the piano on Sundays, etc.). Instead, half the opposition came roaring in for the day on old bangers and motorcycles – several wore jeans and ate lunches out of rucksacks.

Their style of play, too, the BM found (to quote Boden’s old joke) was “a stile he couldn’t get over”. None of them had ever heard of P-K4, and whenever the BM “occupied the centre” they either crawled around the side of it and mated him in the corner, or undermined it by some system of remote control, picked up no doubt from the latest “Batsford”. Still they were generous victors – “Hope I shall put up as good a fight when I’m your age, sir!” Indeed, all was cheerfulness and Coca Cola. The organizers were as good-humoured as they were efficient, and W.R. Hartston’s “serious lunch-time talk” was punctuated with laughter which would have “excited the admiration” of Terry Wogan.

But, as Sir Robin Day would point out, the topic under discussion is not the BM, but Christmas. Has Britain ever celebrated a great Chess Christmas, one coming immediately on top of a National Chess Triumph? For a collective triumph one has to go back only two years (Salonika, 1984) and even this may soon be “old hat” for as the BM writes this we are already in the lead at Dubai. But for an individual triumph, it seems we must go back to 1843, when on 20 December, after 14 hours’ play, “Mr Staunton achieved his 11th and final victory in Paris”. As London and Paris were still unconnected by rail or telegraph, the news had to come ploughing across The Channel, and reached the Press only two days later. “The Englishman’s victory”, says Murray, “was received with great enthusiasm, and Staunton was fêted on his return”. Yet owing to the unexpected vicissitudes of the course of the match, he only just got home in time for Christmas.

He had been “gloriously successful at the onset” and by 9 December led +10 –3 =2. At this point Staunton’s two seconds, Captain Wilson (indisposed) and Mr Worrell, returned home, “laissant à leur Champion la tâche facile d’achever un ennemi expirant” (Le Palamède). But St Amant, like Karpov in the late great struggle, refused to “expire”. Though one bad move would have cost not only the game but the match, he played with superb accuracy and sang froid through five more games covering 278 moves in all. Staunton’s substitute second and admirer, the American amateur Thomas Jefferson Bryan, was so alarmed that to boost his hero’s morale he collected several English friends in Paris to turn up and “show the flag” at the 21st game. Staunton then pulled himself together and produced (in Ray Keene’s opinion) one of his four greatest games. The match ended in a blaze of goodwill, Staunton being delighted with his victory and his opponent with his great stand at the end – “J’ai sauvé l’honneur”.

On the eve of his departure Staunton invited several leading members of the Paris Chess Club to a farewell soirée at his hotel – “a prior engagement prevented M. St Amant from being present at the dinner, but he arrived immediately afterwards, and participated cordially in the festivities of the evening”.’

(6421)

Addition on 10 November 2020: The reverse of a greetings card that we received from the late Alessandro Sanvito (C.N. 11821):

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.