Edward Winter

(2020, with updates)

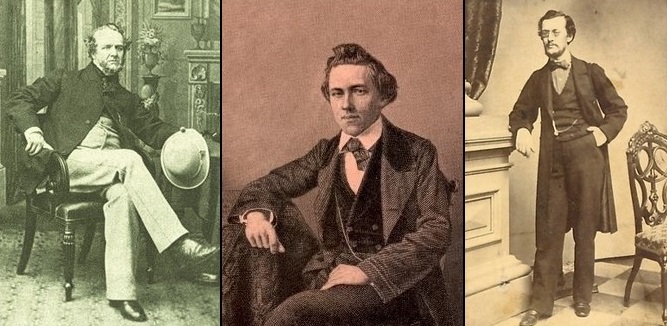

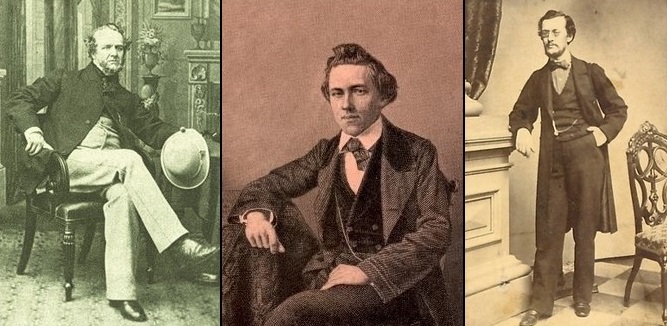

From left to right: Howard Staunton, Paul Morphy, Frederick M. Edge

A detailed overview of many issues in the late 1850s concerning Howard Staunton, Paul Morphy and Frederick M. Edge is in our feature article Edge, Morphy and Staunton. See too Supplement to ‘A Debate on Staunton, Morphy and Edge’ and Edge Letters to Fiske.

Firstly, the present article reproduces from the 1980s, when Chess Notes was a bimonthly magazine, the full published exchanges in a debate involving many chess historians: C.N.s 840, 881, 943, 957, 1012, 1031, 1124, 1149, 1172, 1228, 1269, 1270, 1358, 1416, 1417, 1439, 1440, 1480, 1499, 1569, 1570, 1633, 1642, 1643, 1669, 1700, 1722, 1757, 1758, 1818 and 1932. Our own remarks are in italics.

***

The following unpublished Edge letter has kindly been supplied by James J. Barrett (Buffalo, NY, USA):

‘This letter was commenced a fortnight back.

59 Great Peter Street, Westminster

London Apr. 3 – 1859My Dear Fiske:

Having nothing better to do (excuse this flattering commencement) I sit down to take up my pen for the purpose of beginning a lengthy epistle. As Paul Morphy will very shortly be back again in the United States receiving the slobberifications of his countrymen, this communication may be looked upon as an introductory act of transfer, instruction of consignment, etc. etc. Do you remember giving Paul Morphy a note for me when he was leaving New York, together with documents for Preti and others? Well, when we were both in Paris in the month of October last, he asked me to look in his portmanteau for some thick underlinen, as the weather was becoming cool. I searched as directed, and what should I find but these identical notes; and had it not been for my discovery, they would not now have been delivered. I mention the circumstances because I wish you to understand that it was simply and purely de mon propre avis that I stuck to him from the moment of his arrival. Several reasons impelled me to this. Firstly, revenge against the American players who had not recognized my exertions at the Congress. There was only one way in which I would have received any mark of recognition from them; that was by a vote of thanks of which I should have been proud as long as I lived. I don’t care about my duties during the Meeting, altho you are well aware, Fiske, the other secretaries did little or nothing: what I mean is – the publicity which my articles in the Tribune, Frank Leslie’s, etc. gave to the proceedings. Secondly, pride. The English players laughed at me when I told them about Morphy, and the St George’s in particular made merry at me, although I did not allow my enthusiasm to get the better of my judgement. When Paul Morphy arrived he, at first, was distant towards me; he thought, no doubt, I was desirous of being his second and deriving éclat from his feats. I soon set that thought to rest. But the greatest incentive of all was the determination that he should beat Staunton. In the presence of the London Chess Club, Mr Mongredien said to our hero – “You must be very careful, Mr Morphy, what you say and do with regard to Staunton: he is a wily customer and will find means to back out of this match and throw the onus upon you”. I immediately answered right out – “Mr Morphy, Sir, has come to Europe to beat Mr Staunton and he will beat him with whatever weapons that gentleman may choose”. – I have never acted with so much judgement and energy as in seconding Paul Morphy, and in future years I shall always reflect upon this period of my life with pride. Staunton has lorded it over the English chess world for many long years with the utmost tyranny and where is he now? “Not one soul to do him reverence.” He does not go to the St George’s, and all the members of that club are heart and soul for Morphy. Lord Lyttelton’s letter has damned him in history and write or say what he will, he can never resume his position in the teeth of that epistle. Would you think it possible, Fiske, that Morphy objected to have that letter published, and that I was subsequently obliged to send it off to the papers on my own responsibility, without his knowledge? Ah, I have had a bitter, hard battle to fight with him all through. He objected for a long, long time to having the letter sent to Staunton which commenced the public correspondence between them. When S. sought to entrap him by sending his private reply, Morphy preferred listening to anybody but me, and was about answering also privately. But, singly and alone, I managed to carry the day at last, by dint of argument, entreaty and almost tears. And when Staunton published M.’s letter, suppressing that important paragraph, I said that the latter must now address the British Chess Association and claim justice. Morphy laughed in my face, and replied “the matter need go no further”. What would you have thought of him and me if the affair had so rested? I immediately sat down, boiling with rage, and penned the letter to Lord Lyttelton. I took it right away and submitted it to Mr Bryant (Staunton’s old Second) who returned to the hotel with me and induced Morphy to sign it. Nor is this all. When Lord L. sent his capital reply, P.M. declared that it should not be published. – Seeing it was vain to hope for his consent, I waited until he was out of the way and then sent it to the London papers. Ask Morphy if all this is not true, and then say, Fiske, if I did not act as the very best of friends. Still further, am I not the sole cause of his remaining in Europe and beating Anderssen, without which he would have returned to America uncrowned and unacknowledged?

You have, by this time, read my book. Have I sought my own glory or avenged myself for any supposed wrong? Private feelings have nothing to do with my admiration for his genius; and besides, there is a sweet satisfaction in working heart and soul for a man who is unjust and ungrateful to you. Fiske, how Christian-like one feels when his motives are misjudged and his disinterested acts supposed to cover an arrière pensée, and this is just my position. Through chess in New York and working for your Congress, I lost a good situation on the Herald. Through Morphy I lost an autumnal tour in Russia, the confidence of my father, the affection of my family; nearly broke my poor wife’s heart by forsaking her for him, and to cap the climax am now hated and maligned by himself. And now, how stands the case? I see him safely out of Europe with the greatest reputation that ever chessplayer possessed, and I write a work which will live as long as the game lives and will make him more famous than anything he has ever done. And all for what? To be treated as Alexander served Parmenio.

The main reason for Morphy’s treatment is this: You know that any laborer in the South is regarded as a slave: he has come so to think of me. I made the proposition to him to accompany him to Paris as his secretary, etc., if he would pay my expenses, which I would pay at some future day. He ultimately got to think me a nigger, actually telling me one day, “you will write, you must write, you are paid to write”. No other man but myself would have forgiven him that. I did for he had not yet beaten Anderssen and I was resolved he should. And now that he is at home, I shall still guard his fame here in Europe and woe be to him who dares say aught against Paul Morphy.

In anything I do for Morphy, I am admirably seconded by Löwenthal who downright worships him. I am writing to you Fiske, purely confidentially, and will therefore tell you a secret, which for Heaven’s sake keep to yourself. Staunton has got himself into such bad odour with his countrymen that there is but one club throughout the length and breadth of the kingdom which is favorable to him – viz, the Cambridge University C.C. S. wants to right himself. He cannot get any games for the Ill. Lon. News except those he copies second hand from other papers, and he does not show himself anywhere in chess circles. Besides, he knows that the British Association must, at its next meeting, take action upon Morphy’s appeal to its President, and he is now working to get the meeting held at Cambridge. Löwenthal and I are watching him and we have discovered that he is endeavouring to induce the Worcester Club to give up its claims until next year and it is probable they will. We shall then get the meeting in London and Staunton will be outvoted 20 to 1. Löwenthal is very popular with all the London clubs, and I have now some influence with the leading members and shall have much more when my book is published. Besides, Walker, Boden and Falkbeer are under obligations to me and I can use their columns when I wish. Depend upon it, Staunton won’t make anything by Morphy’s departure, and wherever the association may meet, I shall be present and face to face with the portly Howard. He has been no match for me in diplomacy and correspondence and he will be still less in speechifying.

April 15th 1859 –

Morphy leaves for Liverpool today on his way to New York. Before you receive this, you will have seen him and no doubt will have heard his reasons for so acting towards me. Now Fiske, I ask you, what reasons have I, or had I, for sticking to him? I was no chessplayer or American. I could hope to gain nothing by friendship for him. I do not wish to prejudice you against Morphy: if one must suffer, let it be me, for he is your countryman, your co-editor and your friend. All I ask of you is – do not wrong me also. I have done him nought but good, I have served him as a Christian should his God. Judge me by my conduct since his arrival in New York in ’57 – and as I love and esteem you Fiske, show me some generosity – which I have not received from your countrymen. Morphy is gone. I must now devote my years to business. My father’s affairs call me constantly into the different great cities of Europe. I shall make a point of visiting the chess clubs in my journeyings and you may rely upon receiving occasional readable articles from me for the Monthly.

Hoping you are well and that you will receive Morphy as he really ought to be received for the glory he has cast upon his country.

I remain, my dear Fiske,

Most Sincerely Yours

Fred’k Edge

P.S. – You ought to have the announcement of Morphy’s being on board in the Extras. I wrote to the Captain of the steamer to ask him to do so.’

Below we quote from Mr Barrett’s commentary on this letter:

‘The text shows Edge to be a complicated man. His pushiness is well illustrated in the interchange with Mongredien. Although the latter speaks directly to Morphy, Edge did not let him answer. There are valuable glimpses of Morphy at a very personal level. The relating of his attitude towards Edge as a slave, at least in Edge’s mind, is an electrifying revelation (or opinion).

My own assessment of the Edge/Morphy interlude is that Morphy’s whole trip would have been without half the troubles it encountered had Edge been out of the picture. Edge’s almost paranoid hate of Staunton resulted in his enmeshing Morphy deeper and deeper into a controversy that would not have dragged on the way it did if Morphy had been in control.

Without Edge, Morphy would have played at Birmingham and his results no doubt would have been spectacular. Staunton’s Shakespeare texts were well-known at the time. Morphy has been criticized for not sufficiently appreciating this, but who better than Edge – a writing man himself and “in the know” – should have appreciated it? Yet he continued with his “so much judgement and energy” to press and connive and complicate until he backed both Staunton and Morphy into a corner. And all this took time. Morphy probably would have thrown up his hands and moved on to Paris much earlier than he did, otherwise. This would have condensed his itinerary and left him time and energy for proceeding into Germany, Austria and – who knows – Russia (for Petroff, Jaenisch et al.). Furthermore, this might well have been a jump ahead of Sybrandt, the ubiquitous brother-in-law. As it was, the delay over Staunton, and the rancor in the press reports, allowed the “nervous Nellies” in the Morphy family time to make up their minds and despatch this kill-joy emissary of the family’s “good name” in time to quash all further travels by Paul Morphy. And chess lost much.’

We add two brief comments:

a) Students of this fascinating relationship will need to be familiar with ‘The Morphy-Edge Liaison’ by G.H. Diggle (BCM, September 1964, pages 261-265).

b) The Oxford Companion to Chess quotes from a letter from Edge to Morphy (March 1859): ‘I have been a lover, a brother, a mother to you; I have made you an idol, a god ...’

The question is whether ‘lover’ is to be taken literally. If indeed Morphy were a homosexual, this may well have been one more burden on his ultra-sensitive nature, giving rise to feelings of guilt and accentuating his secretiveness. On the other hand, Edge’s use of the word ‘lover’ may be more casual, with no sexual connotation. In the Fiske letter he writes, ‘... I love and esteem you Fiske ...’

**

Additional remark on 6 August 2023:

As later became known, the ‘lover’ letter was from Edge to Fiske, and not to Morphy. It is shocking that Kenneth Whyld, an assiduous reader of C.N., did not correct our ‘from Edge to Morphy’ comment, that comment being the logical inference from what appeared in the Companion, and especially in the light of what Mr Whyld had written to us on 25 November 1982 (quoted and discussed below).

From G.H. Diggle (Hove, England):

‘The Edge letter is a great “find”, and I think it justifies my estimate of him in the 1964 BCM, with which it seems Mr Barrett largely agrees, though I was wrong in saying that Edge and Morphy did not separate till April 1859 – the rift came three months earlier. It is curious that David Lawson did not publish the whole, which sheds so much more light on his relations with Morphy. (Of course, the letter tells against Lawson’s rather favourable estimate of Edge.)’

Bob Meadley (Narromine, NSW, Australia) writes:

‘That certainly was an eye-popping letter of Edge’s to Fiske, and to some extent it is a pity David Lawson did not publish it in its entirety in his fine book Paul Morphy The Pride and Sorrow of Chess. As you know, the extract he did publish on page 148 of that book contains none of the startling material in the letter, and one can assume from that that he wished to gloss over some of the traits of Morphy by not including them.

It is to be hoped that other letters will be published in Chess Notes to give us a fuller picture of this relationship between Edge and Morphy as it is a fascinating one.

The publication of Edge’s letter in C.N. shows up a difference of opinion between the late Mr Lawson and Mr Barrett on the behaviour of Edge. On page 115 Mr Lawson wrote, “Edge always played a subordinate role in Morphy’s affairs”, whereas Mr Barrett feels that there wouldn’t have been half the trouble had Edge been out of the picture. I’m inclined to agree that there would also have been only half the chess had Edge been out of the picture.

One thing that has sadly always seemed to place historians into one camp or another depended on their view of whether they favoured Staunton’s actions with Morphy. Another matter is Morphy’s love life. David Lawson’s book suffers here and only on page 204 does he say, “What little is known of the women in Morphy’s life, he seems to have had some attraction for them”. Yet Frances Parkinson Keyes says on page 534 of The Chess Players (1961), “I believe I know who the object of his affection was; at all events, I know the family, in which she may have been one of several sisters or cousins, descendants of whom are still living. I could see no useful purpose in violating Creole reserve by making factual use of this episode ...” What an amazing statement, and one might well ask how anyone could be offended 100 years after the event. No-one is responsible for the sins or omissions of ancestors.

There is still a lot to know on Paul Morphy. For example, the only photo in Lawson’s book in which Morphy has anything resembling a smile on his face seems to be in that portrait on page 333 in which he is playing chess against a woman of older years. I would commend to everyone a close examination of this photograph. He was very interested in women if his actions in later life can be believed. Therein lies some of the mystery behind the man. What about all his late nights out in Paris?

Another thing worth knowing would be what P.W. Sergeant told David Hooper “in later years” such that Sergeant felt Edge lied. (See BCM, page 34, 1978.)

I hope Mr Barrett’s letter of F.M. Edge leads to a veritable rash of such publications in Chess Notes. It can only help get closer to the truth.’

For the record, J.J. Barrett informs us that he received the original Edge letter from David Lawson for inspection. Our correspondent xeroxed it and returned it to D.L. We personally believe that Mr Lawson’s decision not to quote the real ‘meat’ of the Edge communication in what aimed to be a definitive biography of Morphy was a grave misjudgement.

From Ken Whyld (Caistor, England):

‘Diggle’s article in the 1964 BCM was what first alerted me to Edge’s duplicity (that is, when I read it in 1964. What a good writer Diggle is). Later I checked Goulding Brown in the 1916 BCM (key section enclosed).’

This reads (page 192):

‘“The campaign of depreciation” by Staunton in the Illustrated London News from the time Morphy left England till the match with Harrwitz began to turn in his favour (Sergeant, page 16) is mythical. The whole story of Staunton’s depreciation of Morphy (before the rupture and Morphy’s appeal to Lord Lyttelton) is simply an impudent invention of Edge’s, and fully justifies Staunton’s denunciation of Edge’s book in the Praxis as “a contemptible publication”. With unparalleled effrontery Edge asked his readers not to take his word for granted, but to turn up the file of the Illustrated to see for themselves. I have done so, and I find him a liar. And I could wish that Mr Sergeant had done the same, before he penned his tremendous indictment of the greatest personality in English chess, and the central figure of the chess world from 1843-1851.’

Frank Skoff (Chicago, IL, USA) writes:

‘Re your C.N. 943 and Edge. From Edge’s book, page 94: “Let him take up the files of the Illustrated London News from the time of Morphy’s arrival in England to his match with Harrwitz; let him examine the analysis of the games, the notes to the moves in that paper, and he will invariably perceive that the American’s antagonists could or might have won, the necessary inference being ‘There’s nothing so extraordinary about Morphy’s play, after all’. A change appeared in the criticism on the eight blindfold games at Birmingham, but, then, Morphy stood alone, and interfered with no-one’s pretensions.”

Morphy arrived in London on 21 June 1858. I therefore checked all the columns in the ILN from 26 June through to 28 August, the issue after that being the one dealing with the blindfold display at Birmingham. What Edge wrote is correct, however unamiably he may have phrased it.

Sergeant apparently erred in stating that the depreciation covered the period “from the time Morphy left England till the match with Harrwitz began ...” It should have read, if he is citing Edge for his assertion, “from the time Morphy arrived in England”.

I also read the 1916 BCM article by Goulding Brown and found it nonsensical, some of it also being refuted by Lawson in his book.

I see someone in BCM has already classed Morphy as a homosexual, though he offers no evidence. Even if it were true, it would not change chess history essentially. Edge’s remark was made in 1859, over 125 years ago; and did someone check the language to see the meaning of the word “lover” in 1859?’

(Here we exercise our right to intervene, as the ‘someone’ referred to. On page 24 of the 1985 BCM, in reviewing the Companion, we wrote: ‘Hidden away on page 217 is what appears to be the first publication of a claim by F.M. Edge that he was Morphy’s lover.’ The words ‘appears’ and ‘claim’ are surely sufficient in themselves to refute any charge of categorical classing. Moreover, we were also suitably cautious on page 111 of last year’s C.N. (final paragraph of C.N. 840), making an identical point to Mr Skoff’s concerning interpretations of the word love/lover.)

‘As for Goulding Brown, I must add that the evidence he produces to call Edge a “liar” would never pass a court test, or any other rational proof. What he does is select the brief quotes that are favorable to his case, ignoring those that are not. In judging what was termed a “campaign of depreciation”, you must look at the whole picture, the Gestalt, if you wish, before you can come to any reasonable judgement. You cannot be selective, choosing only those items that sustain your case, if you think them such. Brown, to elucidate further, apparently is a 100% purist; Staunton either praised or lambasted Morphy or Löwenthal, etc., and thus if you find one quotation, for example, of praise, then the whole case collapses. Brown forgot that Staunton was no fool; he was careful to throw in a bit of praise now and then while he is lambasting his poor victim, thus giving the appearance of objectivity. (I might add that I have read Staunton’s volumes from 1840 to 1852 and all his columns in the Illustrated London News – I am not writing without some basis or evidence,)

Interpretations of what Staunton wrote in the period in question may differ; however, just because Edge’s interpretation does not meet with Brown’s does not mean that Edge is a “liar”. For example, there appears to be quite a discussion in Chess Notes regarding Alekhine’s return match with Capa. Suppose X and Y were on opposite sides of the matter? Would it justify X calling Y a “liar”? Of course not. But that is what Brown does.

One minor point: Brown makes the foolish statement (one of many) at the close of his article re Morphy playing Staunton: “(4) If Morphy only desired a trial of skill (a) Why not at Birmingham? (b) Why not privately at Staunton’s house?” It was a true match that Morphy desired (didn’t Brown ever read about Morphy’s formal challenge?), not a private meeting wherein the results would not count. (There is some rumor that the two did play some private games, but only on Staunton’s proviso that the results should not be made public). Can you imagine such an attitude, say, in Steinitz’s time (which overlaps Staunton’s), when Steinitz was challenged by Chigorin, and Steinitz would only allow the latter to play him privately? What nonsense!

Brown cleverly uses Morphy’s words about “a trial of skill” as though Morphy did not want an official, public match, as he had with Löwenthal, etc. More nonsense.

Now to Diggle’s “The Morphy-Edge Liaison” (BCM 1964, pages 261-265). Here we have an amazing display by the author who, more than a hundred years after the event, knows the motives of Edge, the evil ones of a journalist. This is very clever on his part, the usual argumentum ad hominem approach to avoid facts. By discrediting Edge in this way, he can simply dismiss anything the man wrote. He calls Edge’s book “venomous and untrustworthy”, but he gives no facts other than his subjective reaction to the volume: “malignant participant”, “smear technique”, etc.

When Diggle discusses Harrwitz, he finds Edge trustworthy. Isn’t that odd? Edge lies about Staunton but is truthful about Harrwitz. “Here there was no need for him to stir up trouble or fabricate evidence.” First, what is really meant by “stirring up trouble”? Isn’t that what Diggle himself is doing? (Also, isn’t he a member of that evil clan, the journalist?) What does that term mean factually? Your guess is as good as mine. Secondly, what evidence did Edge “fabricate”? Diggle gives none.

Diggle may not like the flamboyant style of Edge, but that is a different matter compared to factual content. I wish he had made a list of lies by Edge with evidence to back up his assertions. Or did he find it unnecessary since Edge was a member of that evil profession, journalism? I am not impressed by emotional terms used to describe Edge’s conduct and writing, nor do I believe that Staunton, because he often wore flashy clothes and occasionally was as flamboyant as Edge in his writing style, was therefore another version of Edge.

Technically, I can only admire the subtle slanderings of Diggle, e.g.: “Edge was admirably fitted for the position into which he had wormed himself”, “the adroit Edge”, and other bits of fictional twaddle like that. Such writing serves well in literary fiction, but it is out of place in biographical exposition, which requires a firm, factual foundation.

Now, someone might say regarding some things I have written here: Where is your evidence? Strange, is it not, when I write something I must give evidence; but when Brown writes, he gives very little; and when Diggle writes, he gives the least of all. Yet nobody asked for evidence then.

I am being a bit sarcastic, of course, but it illustrates my point. Finally, just to repeat, if anybody wants to discredit Edge by saying he is a liar, a fabricator of evidence, then have him list both the lies and the evidence for them. Secondly, indicate what effect those lies, if any, had on the events in question. And, please, no words derived from fiction writers, and no talk about evil journalists. (Are Diggle and Brown evil? Is Winter evil? Am I evil? Are the BCM journalists evil?)’

Addition on 8 December 2020:

On 18 April 1985 Ken Whyld wrote to us:

‘I haven’t the time to deal with the Edge business, and no doubt Diggle will do it more ably than I could. However, I agree with Skoff that the word “lover”, in 1859 – perhaps even in 1939 – did not necessarily imply anything carnal. (Just as “having intercourse” meant simply holding a conversation.) There is not the slightest doubt that Edge manipulated Morphy. He withheld messages from him and wrote letters purporting to be from Morphy which P.M. had never seen – and this by Edge’s own admission – even boast.’

G.H. Diggle writes:

‘Mr Frank Skoff’s vigorous contribution and his generous defence of Edge give a new turn to a famous controversy which has now ebbed and flowed over 125 years. When I wrote “The Morphy-Edge Liaison” in 1964 I was a “fiery youth” of only 61, a lifelong admirer of Staunton who for four decades had witnessed my hero denigrated in potboiler after potboiler not only as the “cowardly evader of Morphy” but a producer of “devilish bad games”. As I considered that the main source of all this was Edge, I launched forth my “counterblast” in an attempt to redress the balance. If I have now lived to be myself “counterblasted” out of my “wheelchair”, I must accept this as one of the hazards of indiscreet longevity.

I have re-read my “thunder” and note Mr Skoff’s “objections” to my phraseology.

Mr Skoff says that I call Edge’s book “venomous and untrustworthy”. Not the whole book, nor do I altogether “dislike his flamboyant style”: “The book bubbles with joie-de-vivre and abounds in racy anecdotes – the smallest incident is presented vividly and effectively ... Quite apart from this, as Edge himself says in the Preface, he was an eyewitness of so much that ‘if I did not chronicle the history of Paul Morphy’s travels in Europe, nobody else could’ and subsequent chroniclers would indeed find it difficult to get on without him. Unhappily, however, Edge is all too often more of a menace to a later historian than a help. For the book, with all its merits, is in certain parts one of the most venomous and untrustworthy in the whole of chess literature.”

“Malignant participant”. I do not think this is unfair, especially after Staunton (whose own conduct in many respects cannot be excused) had finally broken off the match. Morphy knew that public sympathy both in London and Paris was on his side, and wanted to close down the whole affair quietly. He was twice frustrated by Edge, who drafted a letter to Lord Lyttelton and pestered Morphy into signing it – when the reply came Morphy was content and did not want it published – “seeing it was in vain to hope for his consent I waited till he was out of the way and sent it to the London papers”. It could be argued that though this was treacherous, it was not “malignant” – “he only wanted to clear Morphy’s name”. In view of Edge’s animosity to Staunton, I “leave it with the jury”.

“Smear Technique”. I quote in support a passage from Edge (Chapter 4) re Staunton’s attack of pneumonia in October 1844 which prevented the third match with St Amant. It was well known in Paris at the time, and accepted by all authorities afterwards, that it was “a very serious illness”, that “for some days his life was in danger” and that he was left with a permanent weakness of the heart (H.J.R. Murray, BCM, 1908). Edge, however, writes: “Stakes were deposited for the third and deciding match, but Mr Staunton was taken ill, and it was never played. It is unfortunate for Mr Staunton’s reputation that the plea of bad health was so frequently used by him when opponents appeared. And it is more than ever unfortunate in this instance, because the French players declared that, judging from the later games of the previous match, it was obvious that Mr Staunton would have succumbed to their champion if the third and deciding heat had not been prevented by the Englishman’s indisposition. And many of them even affirm that Mr S. felt this and acted in consequence.” Edge’s “technique” here was to put his “smear” into the mouths of others.

“Stirring up trouble”. See “Malignant Participant” earlier. But it must be allowed that Staunton’s fatal Illustrated London News paragraph of 28 August 1858 was a contributory factor, and gave Edge some good ammunition.

“Fabricating evidence”. I was of course referring to Edge’s story of Staunton’s depreciation of Morphy’s play, denounced by B. Goulding Brown, who had checked the ILN column himself, as “an impudent invention”. Goulding Brown was well-known in our chess circles as a strong player, a scholar, and a gentleman, and without hesitation I took his word rather than that of Edge, who was on his own statement “no chessplayer” and therefore incompetent to express an opinion on the fairness or otherwise of Staunton’s notes. But Mr Skoff has now examined the ILN himself, and suggests that Goulding Brown was taken in by the praise of Morphy which he found – it was only put in by Staunton to give an air of impartiality. While giving full weight to the opinion of a critic of Mr Skoff’s standing, I can assure him that if Staunton was “no fool”, “B.G.B.” was no fool either.

“The adroit Edge”. I see no harm in this. “Adroit” is defined in the Oxford Dictionary as “dexterous and skilful”. Edge was both – an agile-minded and able man.

“The position into which he had wormed himself”. Objection sustained. Though the evidence is circumstantial, it is I think enough to confirm that Edge angled for the position and got it. But this was a legitimate ambition and not a sinister one. “Wormed himself” is too strong and the “Right Honourable Gentleman” withdraws the expression.

To sum up. The difficulty in assuaging Mr Skoff’s thirst for “factual content” is that in Edge’s case there is (or was in 1964) practically nothing to go on outside his own book – his contemporaries give us no help as regards the man himself. As we do not know what other people said about him, he can be judged only by what he said about other people. My impression of this was sometimes far from favourable – I did not pull my punches and one or two were arguably “below the belt”. But, as Mr Skoff observes in another connection, “you must look at the whole picture”. So I will end by quoting the opinion of the man who knew more about Morphy than all of us put together – the late David Lawson. We were in frequent correspondence in the seventies while he was preparing his great work. His first letter (20 June 1973) opens: “It is almost a decade since I read your interesting article on Morphy and Edge in BCM. With most of it I am in agreement – to some of it I would take exception. But you cover their relations very well.”’

(End of G.H.D.’s contribution.) In reply to a point raised in C.N. 881, David Hooper (Bridport, England) informs us:

‘From time to time and over many years from the early 1930s I met Sergeant at the Guildford Chess Club. I was honoured to meet the great authority on Morphy, whom we both idolized. I accepted what Sergeant wrote. Doubts came years later, about 1946 I believe, after König had enlightened me about Staunton’s contribution to chess strategy, a contribution I also discussed with R.N. Coles and which may first have been noted in modern times by Golombek. I then became interested in Staunton in a general way and came to see that he was not as black as Sergeant painted him. I was neither alone nor the first to understand this and, of course, these views became known to Sergeant. Naturally we discussed this. I don’t think he ever changed his interpretation of events in Morphy’s time but he expressed some doubts as to whether he should have accepted so much uncorroborated evidence from Edge.’

A lengthy four-part review of the Oxford Companion to Chess appears in the February, March, April and May-June issues of the APCT News Bulletin (P.O. Box 305, Western Springs, Illinois 60558, USA). The writer, Frank Skoff, deals mainly with the Morphy/Staunton/Edge affair, and the concluding part offers the most vigorous and detailed defence of Edge we have seen.

Mr Skoff’s central thesis is that the Companion is too harsh on Morphy and indulgent to Staunton, and he criticizes B. Goulding Brown, G.H. Diggle and R.N. Coles on the same grounds. Support for this, in no uncertain terms, comes from Dale Brandreth in a letter published in the July number: ‘... the fact is that the British have always had their “thing” about Morphy. They just can’t seem to accept that Staunton was an unmitigated bastard in his treatment of Morphy because he knew damned well he could never have made any decent showing against him in a match.’

We regret the polarization of views, but it is all gripping and essential reading.

From Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA):

‘Re. the Staunton affair: I have never doubted Staunton’s importance either world-wide or to chess in Britain. As an organizer and promoter his place is secure in chess history, as is also his place as a player (even Fischer agrees there!). His treatment of Morphy was perhaps no worse than his treatment of others, except that in many ways Morphy had the naïveté of a child, and that made Staunton’s behavior even more reprehensible. What Skoff objects to in the Whyld-Hooper treatment in the Companion – and I am forced to agree – is their subjective evaluations such as his “weakness of character”. What was that? Did he steal, lie, cheat, chase women, smoke strong cigars, drink to excess ...?? Not all of the above would be regarded as character defects by many, but to state such things without saying what his faults were and without supporting evidence is the very thing that I think is reckless and unjustified. Staunton certainly did have at least one real weakness of character: his constant verbal abuse of, and sly innuendo towards, those he disagreed with or whom he wished others to see in an unfavorable light. Hooper and Whyld are both my friends and so I do not want to make more of this than it deserves, but I think their opinions have been subtly distorted by over a century of smearing Morphy by those contemporaries who could not stand the fact that this tiny young fellow was their total master on the chessboard. I have always sensed a tinge of arrogance in Morphy that undoubtedly and understandably raises the hackles of many who may have sensed the same in him, genius or not. I think Capa had much the same condescending air at times, and there too it served him poorly. For example, had he really wanted a match with Em. Lasker early in his career, a humble approach might have secured him the contest, but his rather haughty approach only brought out the worst in Lasker, and the latter naturally found many excuses for not playing the one he knew to be truly dangerous in the period 1910-14. Overall, I think Lasker erred there because he may well have won a 20-game match vs Capa earlier on, whereas after 1913 I think it was at best a 50:50 proposition. I would have favored Capa by at least 6:4 by 1914, though Lasker surely would have been no push-over.’

Ken Whyld writes:

‘Hooper and I spent some effort in writing the Companion to avoid words that have a different meaning across the Atlantic. It appears from Skoff and Brandreth that over there “character” means “morals”, which was not what we were discussing. The Marquis de Sade had a strong character but that did not make his morals praiseworthy. It should be remembered that this remark about “weakness of character” was made as one explanation of Morphy’s utter failure to build a legal practice. What is Skoff and Brandreth’s explanation? Is there any achievement of Morphy’s which we failed to praise, and that fully?’

Frank Skoff writes:

‘I owe an apology to Mr Diggle for being so late in my reply to his critique (C.N. 1012), but since we are discussing the eternal truths of journalism, perhaps time is not of the essence. I concede that Mr Diggle used “adroit” fairly to describe Edge. Nonetheless, under the circumstances my error may be understandable; Mr Diggle hurled so many verbal brick-bats at him that it was practically impossible for me to notice one of them was actually a rose, the solitary missile of mercy amidst the furious fusillade.

Ascribing causation (or motivation) to human actions is often extremely difficult. Some would ascribe the collapse of the Morphy-Staunton match to Staunton, some to Edge, some to mere accident, some to an Act of God under very suspicious circumstances; others would find the cause in socio-economic factors, or in the effects of climate (Parisian air and water pollution) upon character and subsequent inevitable action, or in the genetic code which, step by step, worked its way inevitably to the final dénouement. Others believe the whole matter ended tragically because of the poor relationships of the individuals involved with their respective parents; still others would ascribe the tragedy to some sexual origin as compared to those who found the fatal flaws in the liver, the kidneys, the gall-bladder, the pineal gland, tangled neurons, weak synapses, etc. Despite the difficulties in biographical interpretation, one must look at all the evidence and interpret it as best one can, taking care to avoid dubious speculation or silly idolatry.

I cannot find in my analysis of Brown and Edge in the APCT News Bulletin where I suggested “that Goulding Brown was taken in by the praise of Morphy which he found – it was only put in by Staunton to give an air of impartiality”. I hope I didn’t put on the mantle of omniscience as to Staunton’s motivation; if I did so, it was wrong. Perhaps Mr Diggle can clarify the reference for me. In any case, to settle the point definitively, I conceived a brilliant idea: why not arrange a seance to contact Staunton’s ghost in the other world? Upon being contacted he was most vehement in his protestations, employing some awful language, like “puerile imbecilities” and other outrageous phraseologies too violent and abusive for me to repeat here. I positively will not invite that ghost to any of my future seances! Since then, however, some scientific authorities, probably envious of my innovative approach to historical research, told me bluntly that “information” gleaned in that way is worthless because a seance does not meet the rigorous requirements of the scientific method. What rotten luck¨! For a while I thought I had something.

But I must become serious before someone accuses me of trifling with a sacred subject. My thesis still remains solid: Edge told no lies. The cause of all the argument and confusion must ultimately rest upon the shoulders of Sergeant, who read Edge’s statement that Staunton’s annotations underwent a “change” of “tone” or “tactics” during a certain time frame (the period between Morphy’s arrival in England up to the time of the Harrwitz match). In that period the annotations went from having “scarcely a word of commendation for Morphy” to the high praises of the Harrwitz match, a rather obvious fact, though its cause may be arguable. For his Morphy book, Sergeant created his own phrasing for what Edge had called a “change” of “tactics” or “tone” (a); he called it Staunton’s “campaign of depreciation” (e), a highly inaccurate summation of Edge. (Incidentally, a “campaign” implies an organized structure whose conscious aim is to carry out its purpose of “depreciation”. Edge, however, never used either term.)

The clearest road to understanding is to read Edge first, carefully noting his criterion in the aforesaid “change” (a). Then as one reads Brown, one will soon see that he is completely unaware of it, understandable enough because he has just reviewed Sergeant – not Edge – and is bent on disproving the “campaign of depreciation” (e). Since initially both writers have vastly different criteria to start with, they can hardly show the same results in their analyses; having different targets, their paths will not cross except by chance.

However, this inevitable, huge disparity in results is increased even further by the differences in the limits or restrictions under each criterion. Edge restricts his criterion by three limits: (b) the time frame; (c) the excluded simuls; (d) the restriction to annotations only. Brown, on the other hand, has only the one limit given him by Sergeant – (b) the time frame – and naturally follows it; unfortunately for him, Sergeant did not mention that Edge excluded the simuls (c) and restricted his view to annotations (d) only. All this led Brown simply to look for any praise anywhere in the columns to refute the “campaign” charge (an easy task when using the (e) criterion instead of the (a) and being unaware of two of the three limits in Edge), after which he called Edge “a liar”. There is nothing really complex or intricate about the preceding explication of Brown and Edge; in fact it possesses all the crude subtlety of the obvious. (Brown’s failure to check Edge was not due to any malice or defect of character; upset by Sergeant’s phrasing, he just made a simple mistake, something which could happen to anyone.)

A look at the circumstances or context involving the Edge statement may be useful. At the Birmingham 1858 meeting Staunton had agreed to the match except for the “exact date” (see Morphy’s letter, 6 October 1858 in Lawson, page 140). A few days later, on 28 August, Staunton published his shocking “Anti-Book” statement, declaring that: “In matches of importance it is the inevitable practice in this country, before anything is settled, for each party to be provided with representatives to arrange the terms and money for the stakes. Mr Morphy has come here unfurnished in both respects; and, although both will no doubt be forthcoming in due time, it is clearly impossible, until they are, that any determinate arrangement can be made”. He also added that the wealthy Morphy wanted the stakes reduced from £1,000 to £500. (My comment on this secondary issue: First, if Staunton had any complaints about any phase of the match, why didn’t he mention them at Birmingham? Second, why didn’t he simply write Morphy as to the obstacles, easily taken care of, which would be the formally correct way? Instead, he resorts to his public column. Finally, isn’t Staunton saying in effect that he will play the match once these two obstacles are removed? And there is no mention of any literary contract.)

Edge’s position: “Shortly after that” (the Anti-Book statement) Staunton changed his “tactics” or “tone”, between the time of that statement (after 28 August) to the time of the praises of the Harrwitz match (5 September, etc.) “when Mr Staunton’s tone was suddenly altered”. It is quite obvious that Staunton had gone from sparse praise to laudation; the question as to the accuracy of any annotations is patently beside the point. (Note again that Edge never said anything about any “campaign of depreciation” but wrote of a change in tactics or tone, from sparse praise to laudation, hardly an earth-shaking finding. Brown, on the other hand, demolished Sergeant’s “campaign of depreciation” by simply recounting the praises he found anywhere. There you have the whole comedic mix-up in a nutshell.)

The Staunton-Morphy negotiations at this moment must have been tense enough to cause the Morphy side to be wary of Staunton. After all, Morphy had come to play Staunton, arriving on 20 June 1858. Sometime in late June the match was accepted with the proviso that Staunton be allowed a month to brush up on his openings and endings. About two months went by, but still no match. Now the Anti-Book barrage was certainly unsettling enough to both Edge and Morphy, the latter being in favor of letting Staunton write as he wished; eventually he would overreach himself. Edge was suspicious of the “change”. Morphy did not reveal his feelings on the various delays by Staunton of the match, but having waited all this time for some final results, he certainly could not have been pleased with Staunton, especially after the 28 August blast, which produced his vigorous denial. To say that the Staunton-Morphy relations at this point were cordial or excellent is untenable. After the breakdown of the match, Staunton made some very insulting (malignant?) remarks about Morphy (see his columns, also Sergeant)

“Fabricating evidence”: To me that phrase meant the falsification of any evidence presented to a court in a legal case; for example, it could be the altering of a murder weapon or a document, the forging of a document or letter, etc. That meaning could not apply to Edge since he took his evidence from the same columns Brown did. Since both men used the same source, I was baffled as to how it could be “fabricated”. Mr Diggle clarified matters by explaining that he referred to the so-called “campaign of depreciation”, which I have just re-analyzed and refuted.

Edge’s book: “... with all its merits, is in certain parts one of the most venomous and untrustworthy in the whole of chess literature”.

“Smear technique”: Edge is quoted re the possible third Staunton-St Amant match in 1844: ‘“It is unfortunate for Mr Staunton’s reputation that the plea of bad health was so frequently used by him when opponents appeared. And it is more than ever unfortunate ...” Edge’s technique here was to put his smear into the mouths of others.’ How does Mr Diggle know that this is true? Now he has donned the mantle of omniscience. Isn’t it also likely that Edge was merely reflecting the biased views of the French, who are mentioned in the brief history Edge was setting forth and which encompassed this statement? In any case, let’s assume Mr Diggle’s view is accurate; Edge’s statement then becomes a harsh and unkind remark, but it does not necessarily follow that everything Edge wrote was therefore unreliable and unworthy of trust in other areas. Staunton himself made similar remarks – see my review – and must therefore be classed as “venomous and untrustworthy” in certain areas as Edge. Now that both Staunton and Edge are disposed of as unreliable, where does it leave matters?

As to dishonesty, one must not overlook Staunton’s excision of the Anti-Book statement quoted in a Morphy letter before publishing it in his column. Also, Staunton, in another letter (15 November 1858), stated he had written to an anonymous friend living with Morphy in Paris, explaining the excised letter; when Morphy denied knowing such a person, Staunton had his chance to crush Morphy completely by identifying the party, which he was certainly obligated to do under the circumstances. Instead, he remained silent, as silent as he did when Edge’s book was published except for a few general words. In practically all his other disputes in his lifetime, Staunton replied; this is the only one in which he was at a loss for words in defending himself. A jury will have to decide that one too.

Re Mr Diggle’s complaint that Edge was the “main source” of Staunton being denigrated “not only as the ‘cowardly evader of Morphy’ but a producer of ‘devilish bad games’”: As to the games, the original quotation is ‘some devilish bad games’ (my emphasis), from lines Morphy had written in a copy of a chess book when he could not have been more than 16 years old, lines not intended for publication and hardly sensational since all masters have played badly on occasion. As to the denigration, it would seem that the rational course to pursue would be to garner all the facts about the matter, then weigh the evidence for and against Staunton to discover the errors which caused a miscarriage of justice. Instead, Mr Diggle, in the main, attacks Edge personally, showing what a repulsive person he was, a procedure which does not add much substance to the matter.

When the Morphy match negotiations broke down after three months or so, not a single chess organization or player of any prominence came out in favor of Staunton (not even his Cambridge CC, which only seemingly did so). Why? Public opinion – and here I can only interpret the foregoing evidence – could only see that Staunton, not Morphy, had finally declined the match and so ascribed its failure, rightly or wrongly, to Staunton. The public was not much interested in any justification.

Had the match been delayed for a short time, after which Staunton said his literary contract made it impossible, nothing more would have been said. But he accepted the challenge and then kept delaying it month after month for one reason or another. Morphy, a visitor to Britain, was kept waiting by Staunton for three months, certainly a most discourteous act, to say the least. Naturally Staunton’s reputation in his homeland suffered afterwards to a large extent, despite a lifetime of toil for the cause of chess, because he failed to meet Morphy.

Nonetheless, the wheel has come to a full circle, and now Staunton is pictured as a saint without fault, Morphy as an introverted and incompetent wimp, and Edge, in some unexplained way, as the villain of the whole affair (see the Oxford Companion to Chess), a point of view more founded on fiction than on fact. Edge’s idolization of Morphy, sometimes hard to take, is at least understandable since he (Edge) knew little of chess. The Staunton biography mentioned, however, beats him hollow in that respect, yet its creators were much more knowledgeable than he and had access to more data. Of course, idolatry is not unknown in chess biographies since the earliest days of chess history.

“Malignant participant”: Morphy, as Mr Diggle says, wanted to end the affair quietly. “He was twice frustrated by Edge, who drafted a letter to Lord Lyttelton and pestered Morphy into signing it – when the reply came Morphy was content and did not want it published – ‘seeing it was in vain to hope for his consent I waited till he was out of the way and sent it to the London papers’. It could be argued that though this was treacherous, it was not ‘malignant’ – ‘he only wanted to clear Morphy’s name’. In view of Edge’s animosity to Staunton, I ‘leave it with the jury’”.

Edge’s publication of the Lyttelton letter was “treacherous” or insubordinate, but it was so to Morphy – not to Staunton – and no doubt was one reason why Morphy fired him. Again, Mr Diggle has donned the mantle of omniscience in knowing that Edge did it only because he hated Staunton. Perhaps, but that is not very helpful in assessing matters, no more than discussing the various people Staunton disliked or hated would be. Assuming for the moment that Edge had not acted as he did and the letter only surfaced last year, how would the case against Staunton be changed? The facts in the letter are still facts, whether published immediately or not, whether published against Morphy’s wishes or not.

The major difference between Mr Diggle and me is that he was interested in presenting an adroit portrait of Edge because he had treated Staunton badly, whereas my objective was to amass whatever facts one could in the Brown-Edge-Morphy-Staunton relationship. I have no real quarrel as to the repulsive portrait Mr Diggle draws of Edge; my only aim was uncovering facts so as to analyze Brown’s charge of “liar”, which simply is untrue. (If anyone has hard evidence to the contrary, I should like to know; and if my analysis of Edge and Brown is not factually based, or is erroneous in some way, I should like to be shown exactly where I went wrong.) Consequently, David Lawson and Mr Diggle may agree on Edge’s unpleasant personality, but that has no relevance to my analysis and does not affect it; the same applies to Hooper’s account of his discussions with Sergeant. Specific facts can help any analysis; discussing personal traits, repulsive or fascinating, rarely does. Perhaps Mr Diggle and I can agree that Edge was a repulsive journalist who gathered gossip, facts, insults, and the like, but to my knowledge he never altered any facts or documents which came into his hands, though like other journalists throughout history, he did publish a letter without permission.’

From G.H. Diggle:

‘Mr Skoff kindly sent me an advance copy of his reply (C.N. 1172) to ensure that I would, like Antonio, be “armed and well prepared”. I do not, however, propose to deal with all his points in detail, for two reasons. First, because he covers a very wide field, and introduces matters outside the scope of my 1964 article, which dealt only with the “Morphy-Edge Liaison” and not the whole Morphy-Staunton controversy. Secondly, because I doubt whether there is as much disagreement between us as would appear on the surface, and we may be in danger of quarrelling about words, emphasis – and epithets. For example, Mr Skoff complains that we British chess pundits treat Staunton as “a saint” and Edge as the root of all evil. This is of course an exaggeration – but we all know what he is getting at. While it is agreed on all sides that both Staunton and Edge committed excesses in print, Mr Skoff espies an unwritten British law that what is allowable in Staunton is not allowable in Edge. If Edge makes an outrageous statement it is typical of the fellow – if Staunton makes one to a fake correspondent it is treated rather as the unfortunate eccentricity of a great man, and we whisper confidentially to our readers, “There are people who refuse to credit the existence of these correspondents” (Murray, BCM 1908). But even Staunton’s enemies admitted that he had great qualities; moreover, though a very bad controversialist, he was less “greasy” and insidious than Edge. Staunton in one of his moods would indulge in a glaring mis-statement which could hardly be called false, so remote was the chance of anyone believing it. Edge was cleverer and more plausible – his methods are illustrated by his unctuous remark (mentioned by Mr Skoff in C.N. 1172, page 76): “It is unfortunate for Mr Staunton’s reputation that the plea of bad health was so frequently used by him when opponents appeared.” Edge writes as though this was common knowledge, yet it is quite untrue. “When opponents appeared” suggests that he pleaded bad health to avoid playing them – what he did was to play them and plead bad health afterwards if he lost!

There is one important point, however, which (though it does involve a dispute about words) it would be discourteous to ignore, as I know Mr Skoff feels strongly about it and defends Edge with meticulous detail, even introducing a “little algebra”. This concerns Edge’s “impudent invention” (Goulding Brown’s words quoted by me with some relish in 1964) of Staunton’s “campaign of depreciation” (Sergeant’s words, not Edge’s, as Mr Skoff points out). What Edge wrote was: “Shortly after that Mr Staunton changed his tactics ... Let the reader take up the files of the Illustrated London News from the time of Morphy’s arrival in England to his match with Harrwitz – let him examine and analyse the games, the notes to the moves in that paper, and he will invariably perceive that the American’s antagonists could or might have won, the necessary inference being ‘there’s nothing so extraordinary in Morphy’s play after all’ ... When, however, the match with Harrwitz came off, Mr Staunton’s tone was suddenly altered, and this gentleman, who previously had scarcely a word of commendation for Morphy, now talked of combinations which would have excited the admiration of La Bourdonnais.”

Three questions arise:

(1) Does this amount to an accusation that Staunton at first systematically disparaged Morphy and suddenly changed to praise as a matter of tactics?

My own opinion is “Yes”. More important, both Sergeant and Brown, though one was attacking Staunton and the other defending him, clearly thought so too. “The reader will invariably perceive ...”, wrote Edge. Sergeant’s “campaign of depreciation” may have been an ebullient translation, but scarcely a distortion of his meaning. Nor do I believe that B.G.B. was so mesmerized by Sergeant’s expression that he failed to check what Edge had said. It must be conceded, however, that he did, quite unnecessarily, over-egg the pudding by dragging in additional ILN items praising Morphy which, as Mr Skoff’s “algebra” demonstrates, were outside Edge’s “equation”.

(2) Was the accusation true? In my own opinion, “No”. Edge was wrong in saying that Staunton had “scarcely a word of commendation” for Morphy’s earlier games – in two cases he praises M. twice in the same game. But he did praise the Morphy-Harrwitz games more than the previous ones. Goulding Brown solves Edge’s “mystery” in four words. “They were better games.” This is confirmed by Steinitz, who spoke of “a marked improvement” in Morphy’s play as compared with his games against Löwenthal. The “change” Edge talks of was in Morphy’s play, not Staunton’s tactics.

(3) Even if not true, did Edge honestly think it was? This is, of course, the “thousand dollar” question – but who is to answer it? As I have been told not to go looking into Edge’s mind (especially if I happen to have donned “the mantle of omniscience” – a favourite vestment of mine, in the opinion of Mr Skoff), I will resort to my other vexatious habit of “leaving it with the jury”. They should pay every attention to Mr Skoff’s argument that Edge was not so much attacking Staunton as beginning to worry about what he was up to – first “anti-Book” – still no date fixed – then “sudden praise” etc. On the other hand, in assessing Edge’s attitude and reliability, they are entitled to take into account any earlier remarks he had made about Staunton’s ILN column. On 6 August, writing to Fiske, he alluded to “those mean, sneaking notes which have constituted Staunton the Chess Pariah of the London World”. Earlier still, writing to Maurian on 24 July, he reported: “Morphy’s scores with the leading players in offhand games stand as follows ...” Then follows the curious allegation: “Staunton will not publish them” [i.e. the figures ] “they being too much in Morphy’s favour”. Both the allusion and the allegation were made weeks before any trouble between Staunton and Morphy had arisen.

As regards my general treatment of Edge, Mr Skoff feels unable to award me very high marks for “factual foundation”. There is indeed a sort of “no man’s land” between fact and fiction into which I sometimes strayed, playing Edge by ear rather than from the music. But at that time I had practically no music in front of me except Edge’s own book. There is no more finality in chess historical research than in analysis of the Chess Openings. On the evidence then before me I portrayed Edge as an able, pushing, thick-skinned and sometimes unscrupulous journalist. But thanks to David Lawson and to Chess Notes much more about him has now come to light. His letters to Fiske and Maurian in Lawson’s book and his extraordinary letter to Fiske published for the first time in C.N. 840 suggest deeper waters. While they scarcely show Edge in any pleasanter light, he can no longer be dismissed solely as a journalist who thought he was on to a good thing. He is revealed (strangely enough for a man of his undoubted ability) as an almost adolescent Morphy-worshipper – a sort of vicarious bully where Morphy’s play was concerned who regarded any suggestion that M.’s opponents “could or might have done better” as a malevolent insult to the young master. And when Morphy finally discarded him, his tone verged almost on the hysterical. Everyone, from the officials of the American Congress in 1857 to Morphy himself in 1859, had treated him shamefully. Mr Barrett perhaps says the last word when he describes Edge as “a complicated man”.

One minor point. In reply to Mr Skoff’s enquiry in his third paragraph, his suggestion that “Goulding Brown was taken in, etc.” was not made in the APCT News Bulletin, but in C.N. 957.’

A letter from Ken Whyld runs:

‘Skoff has performed a valuable service in segregating Edge’s opinions from Sergeant’s. However, Edge talks of a change of “tactics” in Staunton’s annotations, from “scarcely a word of commendation” to “high praise”. The word “tactics” implies that the change was not connected with the merit of the games themselves. Does anyone doubt that the games against Harrwitz were much superior to those played by Morphy when he first arrived in England? Edge, being less than a patzer, said, “There are more flies caught with honey than with vinegar” without explaining how the gad-fly was to be caught.

What the Morphy-worshippers have not explained is why they attach importance to the non-match. Nobody has ever, as far as I recall, maintained that Staunton was the better player, or that he would have won the match.

I believe that Skoff makes an error of interpretation when he says that Staunton’s 15 November 1858 letter refers to “an anonymous friend living with Morphy in Paris”. Staunton said “a friend in Paris with whom, through my introduction, Mr M. was living upon intimate terms”. This need not be the same as co-habiting.

If Skoff thinks that the Companion pictured Staunton as a saint without fault then he cannot have read the entry. And did Morphy ever employ Edge in a formal sense?’

Addition on 8 December 2020:

Further to the penultimate point above, on 6 September 1986 Mr Whyld wrote to us:

‘My point is that if you say “Smith lives at peace with God” you mean he has a tranquil life, but if you say “Smith lives with God, at peace” you imply that he is dead. To live upon intimate terms with someone is not the same as to live with someone on intimate terms. The second implies cohabitation, but Staunton used the first. It simply means that they would call upon each other without appointments and without presenting cards.’

James J. Barrett writes:

‘Ruminate about this statement of Edge’s: “... and I write a work which will live as long as the game lives and will make him more famous than anything he has ever done [my emphasis]. This is possibly the most remarkable insight into Edge’s state of mind at that time in the whole letter. An honorable mention might go to the masochistic/martyr-complex implications of the passage beginning “... and besides, there is a sweet satisfaction ... etc.”. Psychoanalyst Fine would have a field day.’

We offer one research idea on Edge, related to his many books, booklets and open letters on British and American history and current affairs. Is there a historian who could examine these works and offer a judgement on their reliability?

Also from James J. Barrett:

‘Much more light needs to be cast on the “Edge to Morphy” letter quoted in the Oxford Companion to Chess and referred to in C.N.s 840 (page 111) and 957 (page 55) – “I have been a lover, a brother ...” etc. Nothing less than the quoting of the full text will satisfy the needs of accurate chess history. If this letter was ever delivered to Paul Morphy does it make sense that both he and his family would have preserved it if it in any way compromises the man?’

Additions on 9 December 2020:

A letter to us from Frank Skoff dated 17 January 1987:

‘Trying to assess the Edge-Morphy matter by citing, as the Companion did, only a few words from Edge’s letter of March 1859 is silly and amateurish (as well as dangerous) and would be rejected by any first-class university faculty whose students or scholars might accidentally attempt such an unethical procedure. The letter itself runs over 100 lines, of which only about 1½ are quoted! Since this minuscule quote contains a number of metaphors – as you once pointed out – and the vast context in which it appears is missing, readers so inclined can let their imagination flow freely among the metaphors and the unknown context. Under such circumstances, one’s imagination can run riot with all sorts of speculation, revealing perhaps more of the speculator than anyone else; however, it is truth we are after, not imagination.

I have obtained a copy of the Edge letter of March 1859 and believe Chess Notes would be the most appropriate place for it. Would you print it in full if I sent it to you?’

On 28 January 1987 we hastened to agree to publish the Edge letter in full and congratulated Frank Skoff on his find, also asking him whether any information could be added about the whereabouts of the original. He sent us a transcript of the letter on 4 February 1987.

In reply to other points in that letter of ours, Frank Skoff wrote on 18 February 1987:

‘As to “speculation about the brief line quoted in the Companion” getting “out of hand”, it was to be expected since so little material is presented, without context, that many readers will be tempted to unscrew the inscrutable, a situation lending itself to flights of the imagination, since there is so little factual material to form any rational exegesis. The “brief line” is really a verbal Rohrschach Test, a blob of words into which the reader gazes and tells his analyst what forms he discerns, which in turn can reveal any deeply-hidden drives or conflicts. Since a blob by its very nature has no rational appearance or structure to begin with, there can be no consistent agreement about the various forms discerned and hence no rational results about them. If such results could occur, the Test would be useless for its purpose.

My insistence on documentation is the same that impels you to insist on it for contributions to C.N. Without it, we do not progress but simply stay on square one. By documenting the Capa book, you will increase the chances of other journalists following suit, as they may get the idea that such documentation is the way they must go. It might even become chic.

As to Whyld and Hooper giving a general account of the sources of their information, I frankly think it would be a waste of space. The errors in the Staunton and Morphy biographies is [sic] not due to any lack of documentation; one can do that and still turn out questionable work. What is too often wrong is that facts which do not fit their conception of the masters in question are simply ignored, glossed over, or cunningly distorted to fit the aforesaid conception. When I pointed out some of these to Whyld sometime ago, his replies simply omitted any attempt at refutation or even comment on them, which of course convinced me I was on the right path, especially when I had already garnered enough facts to sink a battleship. (I have corresponded with Whyld off and on for over 30 years, and this is our first serious disagreement. My high opinion of him has dropped considerably.)

Actually I think I could get a publisher for full documentation of the Companion. Whyld has the documentation; all he has to do is type it with a good black ribbon, after which photocopying takes over. He may even have the material in that form already.

... Facts have never bothered me since one must face them sooner or later. If Morphy were positively proven to be homosexual, it would not bother me because it would then be a fact. However, what has been presented so far are pseudo-facts, quasi-facts, the pitifully inadequate lines of the Edge letter, in which it is impossible to discern any solid fact; it has all the earmarks of a smear. ... Now that the full letter will be in C.N., the air will be cleared, though the error will live on forever under the banner of the Oxford U. Press in the Companion. So much for justice ...

I never intended to get into the Morphy-Staunton-Edge question, but I have, to the neglect of my own researches into Chicago chess history ...

Perhaps some further explication of the question of dates ... : Whyld did give me the day involved (“25) but would go no further, which puzzled me a bit. After all, if you make a list of the dated letters in Lawson, you will be able to make a good guess as to the date in question. I quite understand the use of years only in giving birth and death dates of individuals, but this does not apply to quoted letters as a rule. Innumerable volumes of letters of famous men in the arts and sciences have been published the last century, always with the complete dating unless it was unknown.

Before I forget: the owner of the Edge letter prefers to remain anonymous, but, unlike Whyld’s counterpart, allows the full text to be printed.’

On 3 March 1987 Mr Skoff explained why the text sent to us was only a transcript:

‘After a long and occasionally bitter discussion, the owner of the letter would not allow a full copy of it to be sent to you, apparently due to the fear that its commercial value might drop too much, etc. Anyway, I managed to be persuasive enough to get you the crucial page, the last one, containing the Edge-Fiske passage.’

Another extract from a letter from Frank Skoff (dated 11 March 1987):

‘As to “the impression that Edge was writing to Morphy”, many people I talked with on the matter have expressed the same point, but that is only one specific result of suppressing the pertinent context for the quote. Once that gross and unprofessional error was made, I didn’t want to waste my time analyzing incomplete evidence. From suppression of context, all kinds of evil flow.’

On 19 April 1987 Mr Skoff wrote to us:

‘[There is] a general law: Whenever you make a case – whatever K.W. intended that excerpt to mean – you are violating both the laws of logic and of ethics: Logic, because evidence is missing or incomplete; ethics, because evidence is suppressed or not revealed. Don’t be fooled into thinking that because K.W. doesn’t bother explaining whatever he means, that [sic] he is not making “a case at all.” He knows full well some of the implications that readers will see in the isolani – unless of course you assume K.W. is an incompetent writer and mentally retarded to boot.

The “case” (whatever the fragmented isolani means by itself) is whatever the reader can make of it; it certainly does not possess much clarity, yet people will try to figure out some meaning. (Even you and I fell into that blind-alley trap.) Such a “case” is of course a grossly unfair trick – I could use blunter language – that can only lead to misreadings, untruths, exaggerations, deceptions, delusions, distortions, arguments, animosities, etc., many of which K.W. was surely quite aware of and, possibly, desired. Now he is trying to play the innocent (see the 3 March 1987 letter) and says in effect: I didn’t mean any of those things; all I meant was to show how “dangerous and unbalanced” Edge was!!! And so it’s your own fault if you saw other things in the quote, to which the answer is: by suppressing the context of the isolani, you never gave any reader a chance to get whatever meaning you intended, and you are therefore responsible for all the misinterpretations and falsities which resulted, including the smear of Morphy and Edge. After all, it was your job to explain exactly what you meant. And why was it necessary to omit the day of the letter and the party to whom it was addressed? And since when is secrecy and suppression a method of explication? Finally, why didn’t you simply say Edge was “dangerous and unbalanced” and present your evidence? Then at least the reader would have had your contention before him, unproven though it would be. To sum up, the whole affair is disgusting, loathsome, and subtly vicious.

... If you look at the Staunton entry in the Companion, you will see that “a small squabble” is hardly described therein. In fact, Whyld there is trying to soften or ignore the fact that Staunton waited until the last minute – of 90 days of delay – to suddenly discover he had a literary contract, ignoring the fact that such prolonged delay is hardly praiseworthy ... and besides, it’s all that fellow Edge’s fault anyway.

My references, in various letters ... to the unethical conduct of printing excerpts out of context were never answered by K.W.. Other points were also ignored, a few were answered. His omissions reveal a great deal:

F.S. to K.W., 25 February 1985: “I note that somebody in BCM has already dubbed Morphy a homosexual because of the quote in the Companion, which itself never made that inference. But you can’t help what people will say sometimes.” (I had hoped, with that last sentence, to draw K.W. into some discussion of the matter, without success, until 3 March 1987.)

K.W. to F.S., 24 April 1985: “Regarding the Edge letter, we had permission only to quote it in part and not to reveal who has possession of it. I could, no doubt, send you a photocopy of the part quoted in the book if you would like to be satisfied that it is in Edge’s handwriting.”

F.S. to K.W., 8 May 1985: “I do not doubt that the portion of the Edge letter in question is in his hand, but any excerpt from anything is within a certain context and that context is important in evaluating the whole. ... I don’t know what else to say under the circumstances except that in a court of law such partial quotation would not be permissible. I mention this, not in anger but to make my main point: unless something can be documented, why even bother with it?”

K.W. to F.S., 3 August 1985: “By the way, I am puzzled that, in your letter to Diggle, you assume that he wrote the Staunton and Morphy biographies. Every word of the book was written by Hooper or myself.”

F.S. to K.W., 16 December 1985: “As to the promise to you, I hate to point out that if you could not publish in full, you should not have published at all. If you don’t believe me, ask any scholar at Oxford University about the customary practice in citing material without context, etc.” (Never touched on in his reply.)

F.S. to K.W., 24 April-12 June 1986: “It is not very ethical to print only part of a letter and that with elisions too.” (Never touched on in his reply.)

F.S. to K.W., 22 February 1987: “Finally, I cannot understand why you allowed yourself to insert that brief 1859 quote from Edge-Fiske, obviously to imply that Morphy was homosexual. The fact that the owner of the letter wouldn’t let you quote more doesn’t excuse you since you had the same responsibility regarding excerpted quotations that he had. I found the whole business a bit of a shock since you are generally very careful to buttress your assertions with hard facts. Nevertheless it will all come out in the open when the full text of the letter is published ... One major difference between us is that you are over-influenced by elements other than facts. You do not, for example, take what you have written about anybody or anything and say to yourself: could I prove this in a court of law? Are there facts which gainsay it? If you did, you would never have written half the stuff you did in the bios, especially the Edge quote, which is a smear of the rankest odor.”

K.W. to F.S., 3 March 1987: “The quotation we gave shows what a dangerous and unbalanced person he was, which is why we gave it. He clearly regarded Morphy as his creation. You appear to be the only one who has read a suggestion of homosexuality in the quote. You know that the word ‘lover’ had a different colour in the mid-nineteenth century, and you ought to know that Edge was speaking metaphorically and did not mean that he was literally Morphy’s mother, etc. If you get around to reading Edge’s other works you will find confirmation of his unreliability.” (Amazing nonsense filled with non sequiturs!)

F.S. to K.W., 2 April 1987: “I am not the only one who read the quote ... as hinting at homosexuality; other people here who have talked about it had that same immediate reaction. (You might look at Winter’s review of the Companion in BCM too.) What is more astonishing is that you thought nothing of simply citing those few words, even though you had only a tiny part of a large whole, thus smearing Morphy – unintentionally or intentionally, it matters not. Would you have printed those lines had they apparently referred to Staunton? You also knew that most modern readers would not know of the Victorian usage of ‘lover’, but you printed the passage without any attempt to clarify the matter as you are now doing.” (Reply to letter not received as yet.)

F.S. to G.H. Diggle, 23 September 1986: “I have been asking Whyld without success for the few lines cited from an Edge letter in the Companion, but he says the owner of the letter would not allow him to quote more than was given. In that case I replied you should never have cited it at all since to quote material without its context is not a just procedure as any scholar at Oxford or at any other university would be quick to tell you. In fact, it is reprehensible to act that way. Whyld never replied to that obvious fact.” (No reply received.)’

The Morphy entry in the Oxford Companion to Chess (page 217) caused a considerable stir by quoting from an unpublished Edge letter: ‘I have been a lover, a brother, a mother to you; I have made you an idol, a god ...’ For a long time it proved impossible for us to secure a copy of the letter but now, thanks to Frank Skoff (who obtained it from a source insisting upon anonymity), the complete text can be made public here. The first thing to note is that, contrary to the impression given by the Companion, the letter is not addressed to Morphy himself, but to Fiske.

‘59 Great Peter Street, Westminster

London S.W.

March 25th 1859My Dear Fiske,