Edward Winter

Brian Donnell (Portland, OR, USA) quotes from the Norton Critical Edition of Dickins’ Hard Times (edited by George Ford and Sylvere Monod, New York, 1966) a letter written by Dickins to Frank Stone on 30 May 1854:

‘I stand engaged to dine ... with one Buckle, a man who has read every book that ever was written, and is a perfect gulf of information. Before exploding a mine of knowledge he has a habit of closing one eye and wrinkling up his nose, so that he seems perpetually to be taking aim at you and knocking you over with a terrific charge. Then he looks again, and takes another aim. So you are always on your back, with your legs in the air.’

(1876)

From G.H. Diggle (Hove, England):

‘I am sure that Buckle’s habit of “closing one eye ... so that he seems perpetually to be taking aim at you” was actually used by Dickens when describing a minor character in Great Expectations, Chapter X. Here Pip encounters a stranger in the Bar of the Three Jolly Bargemen:

“He was a secret-looking man whom I had never seen before. His head was all on one side, and one of his eyes was half shut up, as if he were taking aim at something with an invisible gun.”’

(1907)

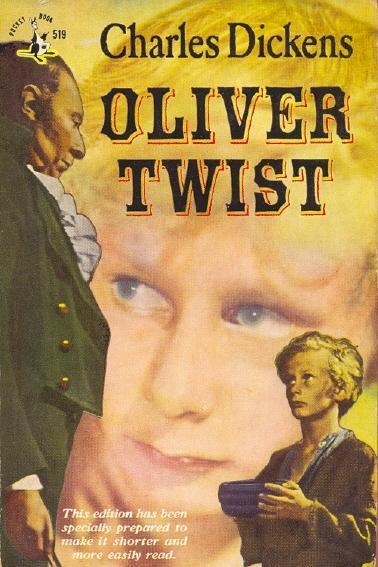

We believe that Fred Reinfeld’s first non-chess book was an abridgment of Oliver Twist (New York, 1948). The front cover featured John Howard Davies in the title role in the film version released the same year, and the last two pages (313-314) had an Afterword by Reinfeld about Dickens’ life and work.

(4859)

Charles Dickens

Some references to Charles Dickens and chess:

The item from Lasker’s Chess Magazine (1905) was reproduced on pages 285-286 of The Treasury of Chess Lore by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1951). A complication is that we see Internet pages stating that the Baltimore Sunday News ceased publication in the 1890s. Has anyone ever traced the newspaper’s original report regarding ‘Victoria Tregear’?

Many writers have placed reliance (rashly, we feel) on the item published in Lasker’s Chess Magazine. It was, for instance, the sole basis for an entry on Dickens in B.J. Horton’s Dictionary of Modern Chess (New York, 1959).

(6906)

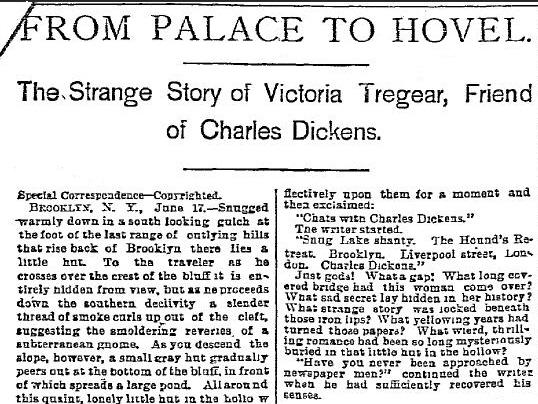

Russell Miller (Vancouver, WA, USA) has found an article ‘From Palace to Hovel’ by Miller Hageman which has the subtitle ‘The Strange Story of Victoria Tregear, Friend of Charles Dickens’. It was published in the Dallas Morning News of 21 June 1891, part two, page 16. The references to chess are in column three.

Caution is clearly still required with this curious matter, and the present feature article will report on further investigations and discoveries.

(6909)

Addition on 17 January 2011:

Mr Miller adds that the above newspaper report also appeared the same day (21 June 1891) in the Cleveland Plain Dealer (page 10), the Galveston Daily News (page 11) and the Salt Lake Herald (page 13). Furthermore, he has traced this item on page 3 of the Wichita Daily Eagle, 4 September 1891:

It has been mentioned that the game Piper v Davie was annotated on pages 394-396 of the December 1916 BCM with quotations from The Pickwick Papers.

We add that pages 119-120 of the May-June 1915 American Chess Bulletin reproduced from the Family Herald an article ‘Great Pickwickian Discovery’, comprising a game (J.H.B. v S. Pickwick) which also had annotations in the form of quotes from Dickens’ novel.

The game, not identified in the article, was Blackburne v N.N., Canterbury, 1903. We gave it in C.N. 182, with Blackburne’s notes from page 392 of the September 1903 BCM. See pages 31-32 of Chess Explorations.

(6937)

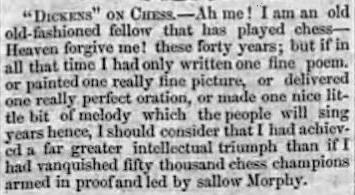

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) points out a brief item on page 1 of the Weekly Georgian Telegraph of 28 June 1859:

Pending further information, this paragraph, referring to Dickens, chess and Morphy, needs to be treated cautiously, and not least because our correspondent has found that the same text had appeared on page 3 of the Washington Constitution of 14 June 1859, but with the quote attributed to ‘Diogenes’.

(6957)

There is an article entitled ‘George Cruikshank, Charles Dickens and Chess’ by Gareth Williams on pages 44-45 of CHESS, April 2004.

Addition on 8 December 2012:

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

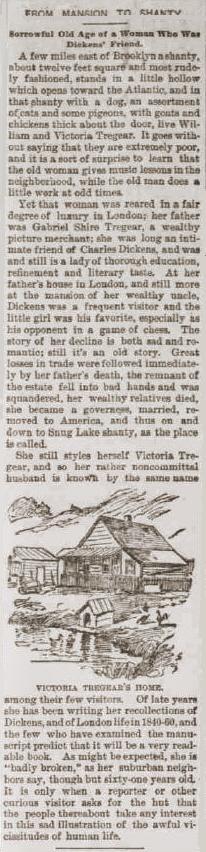

‘The house in which Victoria Tregear often played chess with Dickens was that of her uncle, Hector McLean, “upon Bloomsbury Square”, London, according to an interview with her which was reported in the Tuapeka Times (4 November 1891, page 5). The source referred to in the article was “a recent number of the Sunday Herald (Boston)”. She was reported as living in reduced circumstances with William, her husband, in “Snug Lake Shanty”, near Brooklyn, having emigrated from England.

“I was born on the anniversary of the Queen’s Birthday, and named, after her Royal Highness, Victoria. I was one of 13 children.” She claimed to have been born at 96 Cheapside in 1831, and that her father was “Alderman Tregear”, a “picture merchant”, and her mother Ann McLean, sister of Hector McLean.

This part of the story is corroborated by a baptism entry in the parish register of St Mary Le Bow, City of London, where Caroline Victoria Tregear was baptised on 7 December 1841, having been born on 24 May 1831, the daughter of Gabriel Shire and Anne Tregear of 96 Cheapside, printseller. Although Caroline Victoria was ten years old at the time of her baptism, the birth-date 24 May matches that of Queen Victoria, while 1831 also tallies with the story.

Her father can be identified as Gabriel Tregear, who is listed as a seller of music and prints at 96 Cheapside in Robson’s Commercial Directory of London for 1838 (page 732) and Pigot and Co.’s Directory of London, September 1839 (page 404). He also had a middle name which is usually printed as Shire, but sometimes as Shear or even Shir. The death of “Gabriel Shear Tregear” was registered in the Islington district in the quarter ending 31 March 1841.

Caroline Tregear can be identified on the 1841 census, aged ten, a pupil at a school in Brixton Rise, Lambeth, born outside the county of Surrey (1841 census, National Archives, HO 107/1054/5, f. 18). In the same census, her widowed mother, Ann Tregar [sic] is to be found living in Cheapside, aged 40, a printseller, with four children, Fanny, 15, Sarah, ten, Septima, five, and Gabriel, eight months, and a female servant (1841 census, National Archives, HO 107/722/4, f. 3).

Ten years later, in the 1851 census, “Caroline V. Tregear”, aged 19, a teacher, was in the household of her sister, Sarah M. Tregear, aged 22, a governess, at 121 Holly Mount, Hampstead. Both are described as having been born in London (1851 census, National Archives, HO 107/1492, f. 213).

Later, in the district of Epping, Essex, the marriage was registered of Caroline Victoria Tregear during the quarter ending 30 June 1868 (Volume 4a, page 79).

“I first met Charles Dickens when a mere child of nine years of age at my father’s house”, continues the newspaper article. That meeting was “utterly inconsequential”: he tossed her up in the air, kissed her, told her stories, and gave her a copy of The Old Curiosity Shop. The next time she met him was when she was “a gay, impulsive, facetious girl”, at her Uncle Hector McLean’s house. Of her chess encounters with Dickens, she recalls:

“He was always annoyed when I beat him, and invariably wanted to play another game. I shall never forget how once at midnight Charles Dickens faced me across the board at the end of a play. The game was drawn. ‘Well’, said Dickens, somewhat resignedly, ‘why not?’ ‘Man and woman represent an equation after all. Discriminate as you will in favour of either, they are, when their mutual traits come to be considered, equals.’ A little of Uncle Hector’s choice port wine soon put him into a loquacious mood, and we chatted over the chess-board merrily. ‘Yes’, continued Dickens, ‘the woman who grows up with the idea that she is simply to be an amiable animal, to be caressed and coaxed, is invariably a bitterly disappointed woman. A game of chess will cure such a conceit for ever. The woman that knows the most thinks the most, feels the most, is the most.’ ‘Intellectual affection’, Dickens is alleged to have said, ‘is the only lasting love. Love that has a game of chess in it can checkmate any man and solve the problem of life.’ There was one peculiarity about Dickens as a chessplayer. He always wanted me to move first. He followed my play and accepted all my variations. It was just as in his novels. He lets a character take a lead, and then he simply follows it, studies it, exhausts it. He never created a character.”

The article states that she was for a time governess to the family of the Duke of Norfolk, and that her sisters were governesses in the houses of Russian princes. “At length I married the man whom you see asleep there against that post.” The article contains much other interesting material allegedly recalled from her conversations with Dickens, mostly of literary interest.’

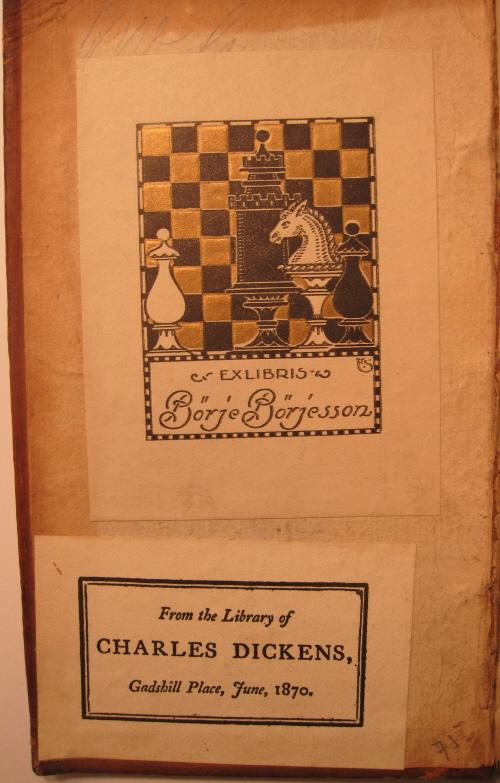

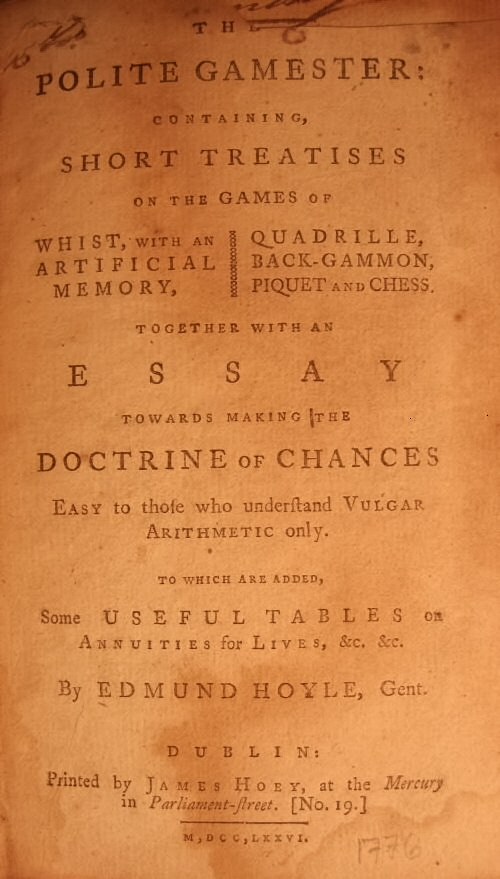

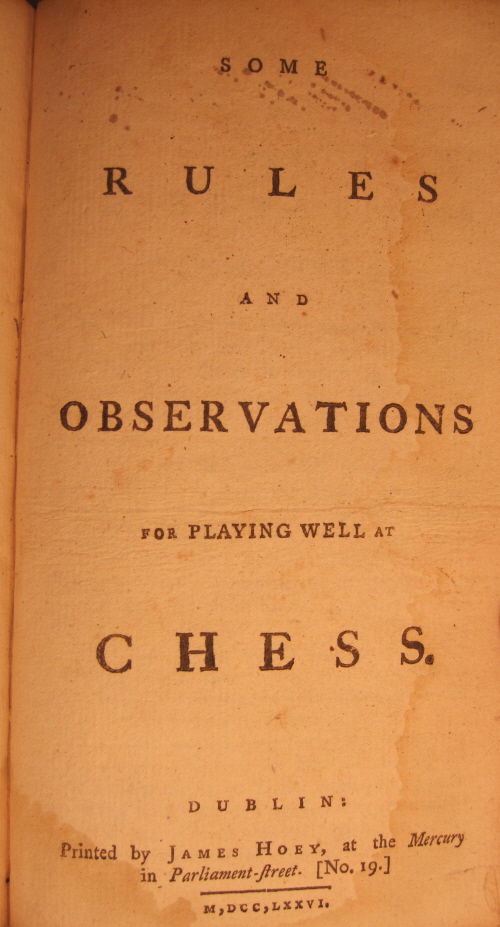

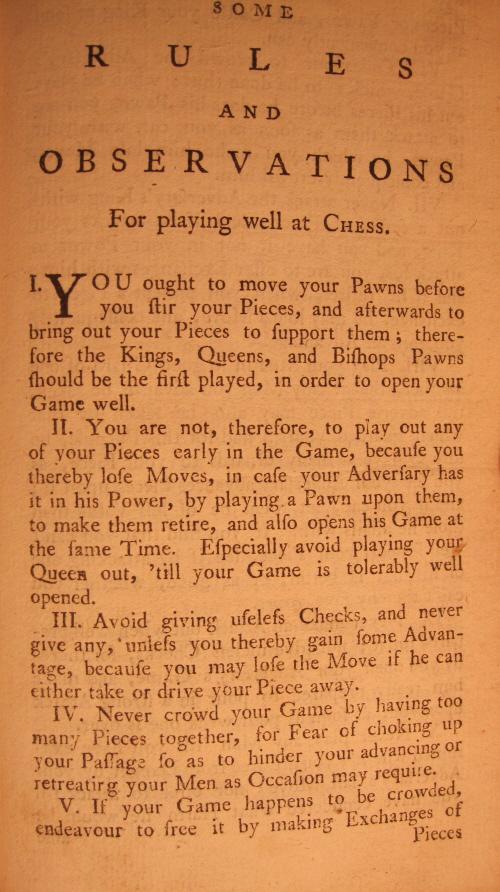

Jon Crumiller (Princeton, NJ, USA) reports that he owns a copy of Edmund Hoyle’s The Polite Gamester (Dublin, 1776) which has the bookplate of Charles Dickens:

A footnote on page 206 of America’s Chess Heritage by Walter Korn (New York, 1978):

‘The hilariously double-edged expression “Chess-Nuts” was first employed as the pseudonym of an anonymous “letter-to-the-editor” correspondent of the chess column in the Illustrated London News in the mid-nineteenth century. The column, along with the signature, was later taken over by Howard Staunton. The fitting appellation was most likely coined by Charles Dickens, who was a student of chess. At the time just before the term first appeared in the column, Dickens described some of his analytical and solving efforts as little “Chess Nuts” – as is collaborated by his letters and by biographies about him.’

Not everyone will share Korn’s view as to what engenders hilarity.

He may have been following pages iii-iv of American Chess-Nuts by E.B. Cook, W.R. Henry and C.A. Gilberg (New York, 1868). Page iv stated:

‘According to historical record, the word-play “Chess Nuts” was first used by a correspondent of the Illustrated London News as a signature. Mr Staunton, thereafter, employed “Chess Nuts” as a heading for little collections of positions given in the Chess Player’s Chronicle and Illustrated London News.’

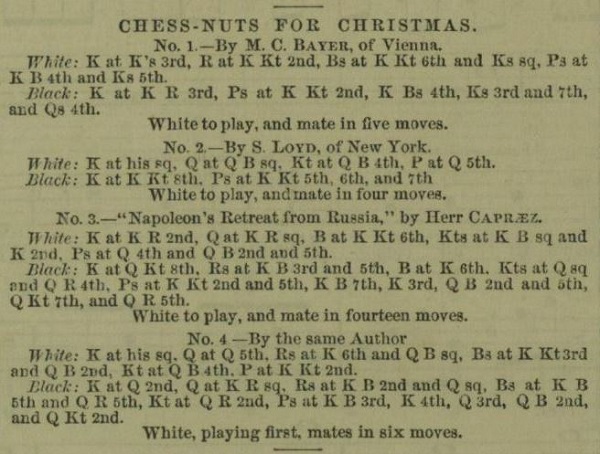

No pseudonymous use of ‘Chess nut’ by a correspondent in the Illustrated London News has yet been found, but one early occurrence of the term in a heading can be shown, from page 610 of the 19 December 1857 issue:

Concerning the above-quoted reference to the Chess Player’s Chronicle, it should be borne in mind that Staunton’s editorship ended in 1854.

Charles Dickens was not mentioned in American Chess-Nuts, but the present feature article includes this passage from the Dallas Morning News of 21 June 1891, part two, page 16:

What grounds did Walter Korn have for referring to letters and biographies?

(8932)

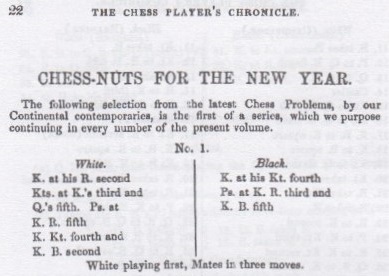

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) notes that the term ‘chess-nuts’ is on page 22 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1850:

(8936)

From pages 110-111 of The Chess Mind by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1951):

‘It often happens that a line of play is too hard to analyse exhaustively within the time at the player’s disposal. He sees a few variations that are definitely in his favour, sees the possibility of one or two clever moves in the distance, sees no immediate refutation and, therefore, adopts the promising line, judging that the continuations will all be satisfactory.

In practice, the judgment that “something favourable will turn up” is true with a frequency that is inversely proportional to the player’s laziness. To the Micawbers of Chess there only happen bad results and occasional pieces of luck when an opponent plays particularly badly.’

(8933)

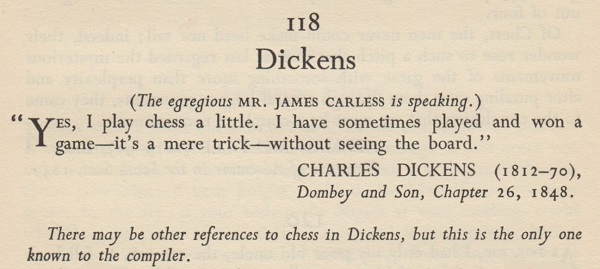

From page 101 of Chess Pieces by Norman Knight (London, 1949):

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) quotes two passages from Bleak House, in Chapters 5 and 20 respectively:

‘“Ah, cousin!” said Richard. “Strange, indeed! All this wasteful, wanton chess-playing is very strange. To see that composed court yesterday jogging on so serenely and to think of the wretchedness of the pieces on the board gave me the headache and the heartache both together. My head ached with wondering how it happened, if men were neither fools nor rascals; and my heart ached to think they could possibly be either ...”’‘Mr Guppy suspects everybody who enters on the occupation of a stool in Kenge and Carboy’s office of entertaining, as a matter of course, sinister designs upon him. He is clear that every such person wants to depose him. If he be ever asked how, why, when, or wherefore, he shuts up one eye and shakes his head. On the strength of these profound views, he in the most ingenious manner takes infinite pains to counterplot when there is no plot, and plays the deepest games of chess without any adversary.’

(11586)

Ross Jackson draws attention to an academic paper, ‘Dickens’s Gamers: Social Thinking in Victorian Gaming and Social Systems’ by Alyssa Bellows (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

(11655)

In a 1919 interview Capablanca was quoted as saying that Dickens was one of his favourite writers (C.N. 12072).

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.