Edward Winter

A tall, apparently unassuming world chess champion. Numerous rivals, each with his own claims and pretensions. In particular, an active former champion liable to be relegated to the sidelines yet widely seen as deserving a chance to regain his crown. Interminable arguments about how the challenger should be selected. Fervid calls for the ‘dictator’ President of FIDE to be thrown out. A general sense of chaos and animosity. We are, of course, describing the chess world of 65 years ago, in the summer of 1937 …

As noted in C.N. 2473, the contract for the 1935 championship match specified that, if defeated, Alekhine would be entitled to a rematch ‘at a time acceptable to Dr Euwe, in view of his profession’. Euwe narrowly won that 1935 contest, and page 393 of the August 1936 BCM reported that when the two players met in Amsterdam on 19 June 1936 ‘the arrangement was then confirmed to begin the return match for the world championship title in October 1937’, in various Dutch cities.

Max Euwe

In the meantime, FIDE was still trying to introduce rules on the selection of the challenger, applicable to subsequent matches. Its congress in Warsaw on 28-31 August 1935 had passed the following resolution:

‘Each year the above-mentioned Committee [comprising Oskam, Alekhine, Louma, Przepiórka and Vidmar] shall draw up a list of masters who have the right to challenge the world champion. Those who in the past six years have three times won or divided the first prize in international tournaments with a minimum of 14 competitors, of which at least 70% are international masters, shall automatically be included on this list.’

Source: Compte-rendu du XIIe congrès, Varsovie, 28-31 août 1935, page 10.

At the following year’s General Assembly (Lucerne, 24-26 July 1936), the FIDE President, Alexander Rueb of Holland, stated that it was for the chess federations comprising the Assembly to take impartial decisions regarding the world championship, whilst also listening to the opinion of the world champion and other leading masters directly concerned. He hoped that the 1937 General Assembly in Stockholm would be able to take a final decision on the drafts already prepared. In Lucerne (25 July 1936) the texts adopted included the principle that the world championship must be decided by a match and not a tournament. (Source: Compte-rendu du XIIIe congrès, Lucerne, 24-26 juillet 1936, pages 5 and 9.)

Alexander Rueb

Subsequently, the Dutch Chess Federation came up with a proposal (given on page 171 of the June 1937 Tijdschrift van den Koninklijken Nederlandschen Schaakbond) that in 1938 there should be a double-round candidates’ tournament bringing together the loser of the return match between Euwe and Alekhine, plus Botvinnik, Capablanca, Fine, Flohr, Keres, Reshevsky and possibly one other master.

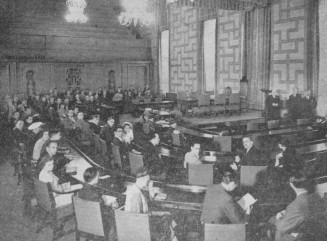

FIDE General Assembly, 1937

The FIDE General Assembly duly met in Stockholm in mid-August 1937, and the detailed report by Erwin Voellmy in the October 1937 Schweizerische Schachzeitung (pages 145-147) presented a tableau of administrative and linguistic confusion. The Dutch proposal for a tournament was turned down by eight votes to four. The Committee had recommended Capablanca as the official candidate, but after an inconclusive first round of voting (Flohr 6, Capablanca 4, Fine, Botvinnik and Keres 1), it was Flohr (with eight votes, against five for Capablanca) who was nominated. Even so, in a subsequent session (on 14 August) Euwe declared that if he won his re-match against Alekhine that autumn he was prepared to meet Flohr in 1940 but that he reserved the right to arrange a private match, either in 1938 or 1939, with Capablanca, who had older rights. If Euwe lost that match, he would make his title available to FIDE, and it would be Capablanca who, in 1940, would have to play against Flohr, whose rights would thus be safeguarded.

José Raúl Capablanca

With Flohr designated as the official challenger, the scene was set for the chess world’s first major outcry against officialdom.

On pages 496-497 of the October 1937 BCM P.W. Sergeant reported Tartakower’s view that FIDE ‘though it can be useful in deciding abstract questions, such as the rules of play in championship matches, when it comes to vital questions gets drowned in a bureaucratic sea of dead paragraphs and premature decisions’. Instead of accepting the attractive Dutch proposal, Tartakower complained, FIDE had tried to be clever and ensure the selection of Capablanca. However, Flohr was chosen, as the result of a ‘revolt’, and ‘we can only designate the intervention of the FIDE in this burning question of practical chess as truly deplorable’.

More indulgently, the American Chess Bulletin (July-August 1937, pages 70-71) observed: ‘It fell to the lot of Dr A. Rueb of The Hague, as the distinguished head of the International Federation, to preside over this polyglot assemblage of chess-playing delegates – a task which no one could possibly envy him’. Chess Review (September 1937, page 193) felt that Capablanca had been hard done by but also that ‘it might be well to point out that the Americans Reshevsky and Fine are probably every bit as well qualified as Flohr to play a match for the world championship!’

Meanwhile the more brash CHESS (14 September 1937 issue, pages 3-4) was outraged:

‘So long as the arrangement of world championship matches remains out of the control of some recognized responsible body, so long will there be chaos in connection with them. The chess world may have to wait ten years for a match; it may witness a series of farcical contests against a third-rate challenger (as has actually occurred); it may, and has, seen a defeated champion wait ten years and more for a return match in vain.

The world has sighed for a champion with a sufficiently knightly spirit to hand the tremendous weapon he has just acquired, his championship, into the hands of some public-spirited committee for their disposition. At last, in Dr Euwe, it has found what it sought. He has promised that, if he wins his return match against Dr Alekhine, he will place the control of future world championship matches in the hands of the FIDE.

The FIDE has shown itself, at Stockholm, supremely unfitted for the task. It has shown already more bias, stupidity and incompetence than any world champion ever did.

Euwe, Alekhine, all the “candidates”, welcomed this wonderful proposal [from the Dutch Chess Federation]. The whole chess world would have welcomed it with open arms.

The FIDE rejected it!

The reasons for this crassly stupid decision are hard to find. You can send ten very wise men into a committee room and they may make a very stupid committee. Invoke the curse of Babel and the confusion is intensified. Add a group of men whose heads are slightly puffed by the positions they have attained, and who are spitefully jealous of any scheme to which their own name is not affixed and you get results like this.

[…] It is almost superfluous to add that the FIDE, still floundering like an inebriated elephant, managed to reject Capablanca’s claims as official challenger in favour of Flohr’s.

Get better men! Mr Rueb and his delegates are not gods. If a labourer makes a mess of his job, he is sacked. If an engineer makes a bad blunder, he loses his job. The present FIDE is obviously incompetent. We should sack the lot!’

On pages 12-13 of the same issue Reuben Fine gave a detailed analysis of ‘Chess Politics in Stockholm’. He said that FIDE’s decisions had ‘produced something little short of consternation throughout the entire chess world’ and he analysed in detail the rejection of the Dutch (AVRO) proposal. The FIDE President and the Czechoslovak delegate, Fine wrote, had deluded the General Assembly into believing that the Warsaw and Lucerne assemblies had taken a formal decision, to be adhered to as a matter of honour, that the federations needed to select a challenger. ‘This statement, though Mr Rueb and the Czechoslovakian delegate must have known it to be false, was repeated time and again …’; Fine added regarding the latter individual that his ‘only object was to “put Flohr across”’.

A couple of further quotes from Fine’s article:

‘It would be an understatement to say that Mr Rueb’s whole conduct of the Stockholm meetings was partisan in the extreme, and that he deliberately intended to make the tournament proposed by AVRO impossible.’

‘We cannot afford to ignore these facts. Mr Rueb is attempting to set himself up as an autocratic dictator in the chess world. Politics instead of a good hard fight have determined the next candidate for the world’s championship. Reason and common sense have been cast aside; personal prejudices rule the day. The interests of living chess have been defeated; and the FIDE with Mr Rueb as president is responsible.’

Alexander Alekhine

CHESS, 14 October 1937 (pages 45-46) quoted from Šachový Týden Alekhine’s reaction to the Stockholm congress:

‘Everything about this decision is incomprehensible and astonishing, particularly the haste displayed. They might have awaited the result of my match against Euwe, on which so much depends! The haste was all the more superfluous as the Flohr match is fixed for 1940. Are no changes going to take place for the next three years? Furthermore, if the whole thing is a question of adding up the successes of individual candidates, why was it necessary for the FIDE to set up a special commission to make out a list of candidates in order of precedence? I was a member of that commission which made out a list of candidates – mainly on the basis of the last known results – and in it Capablanca came first, Botvinnik second …

In my opinion, the FIDE has done positive harm to Flohr by its decision, which has only succeeded in provoking a storm in the chess world and, worse still, even in creating enmity towards Flohr on the part of his colleagues and rivals. All this notwithstanding, Flohr is perfectly entitled to such a match and providing he can muster the necessary resources for it, every champion of the world would be delighted to play with him …

I shall not hold myself bound by the decisions of the FIDE and I am under no obligations towards it. I shall act, should I beat Euwe, according to my own judgment, reckoning with the FIDE as a moral factor only insofar as I find their decisions correct and of benefit to chess at large.

I am having a visit from Mr Piazzini, the captain of the Argentine team, to discuss the question of a possible future world championship match. Argentina and Uruguay jointly wish to organize a mach for the championship of the world in 1939. It is quite understandable that they should wish Capablanca to play in it, but that is by no means decided yet. In any event, I am prepared to play that match with him or with anybody else in the event of my regaining the title.’

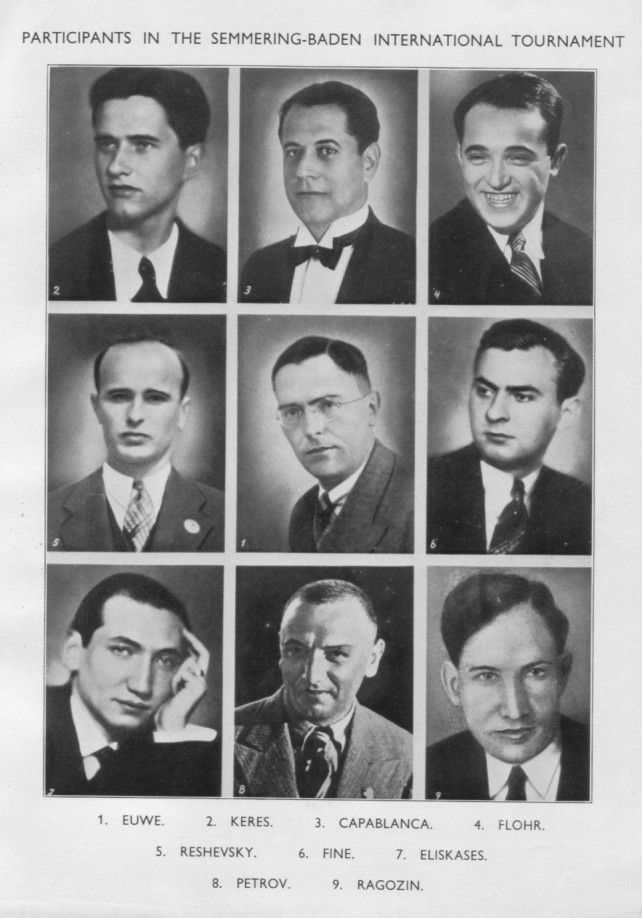

Subsequent practical developments may be summarized briefly. Already by September 1937 (i.e. a mere month or so after the Stockholm congress) Capablanca’s standing, founded on his great triumphs at Moscow, 1936 and Nottingham, 1936, began to lose its shine; at the Semmering-Baden tournament he finished equal third with Reshevsky (behind Keres and Fine but ahead of Flohr) with a score of +2 –1 =11.

Below is an illustration which appeared in the CHESS monograph on Semmering-Baden, 1937:

In mid-December 1937 Alekhine decisively regained the world title from Euwe. The AVRO tournament went ahead in late 1938, but without the status of a candidates’ event. As was reported on page 509 of the November 1938 BCM:

‘… since there have been all sorts of rumours as to a world championship match resulting from this tourney we have been permitted by Dr Alekhine to publish the clause in his contract with AVRO dealing with this question. It runs as follows: “Dr Alekhine declares himself ready to play a match for the world championship against the first prize winner of the tournament upon conditions and at a time to be arranged later. However, Dr Alekhine reserves the right to play first against other chess masters for the title.” So the reader will observe that this clause in no way affects Dr Alekhine’s projected match v Flohr, which is due to take place next year.’

There has probably never been another period in chess history with so many ‘projected matches’ that failed to materialize. The AVRO tournament itself clarified nothing, except that the two ‘Stockholm finalists’, Flohr and Capablanca, finished bottom, in eighth and seventh places respectively.

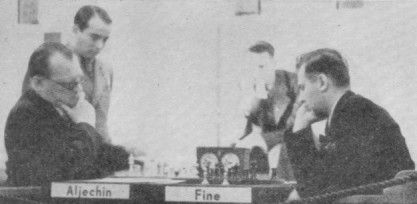

Alekhine v Fine, AVRO, 1938, with Flohr behind the world champion

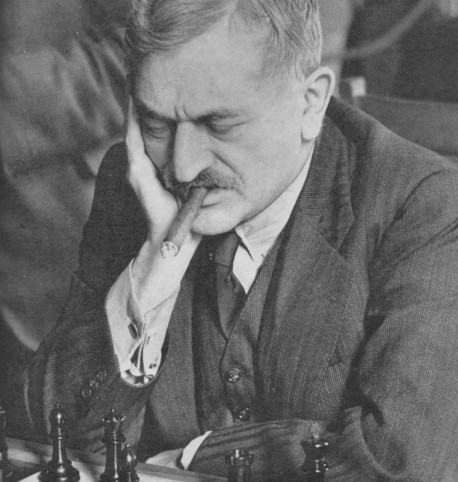

Then there was Emanuel Lasker, who was upset at not being invited to participate in the AVRO tournament. In an interview with Paul H. Little on pages 14-15 of the January 1938 Chess Review, ‘the veteran commented that his own record in tournament play against the leading world masters (particularly against the three other world champions), since his loss of the title in 1921 to Capablanca was enough to qualify him as a candidate who ought not to be overlooked. Dr Lasker feels that Dr Rueb is a foe of the creative master.’

Emanuel Lasker

Asked what the rules for world championship matches should be, Lasker replied:

‘We must disregard specious theorizing. As in all other sports, chess must be judged by results. Hence challengers should be determined by match and tournament play. The latter should be confined to leading candidates. The rules for qualification to these tournaments must be decided by a congress of masters who are authorized and representative. All negotiations must be public – no clandestine bargainings can be allowed. When these rules are formulated, the tournaments to follow will have to be conducted by them to the absolute letter. Race, age or creed must not interfere with qualifications. In the event of a tie among the voting body of masters in deciding such rules, the champion must be allowed the deciding vote.’

Lasker added that a world championship match every two years would be ideal. As regards his own chess play, he commented: ‘I have trained intensively in the last three years and see no reason why I cannot acquit myself creditably.’

But little more than two years after the AVRO tournament, Lasker was dead. Capablanca died the following year (1942), and Alekhine survived only until 1946. In any case, the outbreak of war in September 1939 had already despatched the Stockholm plans to oblivion. Tussling with cold war politics would be FIDE’s next major challenge.

As noted above, FIDE’s position in the mid-1930s was that ‘the world championship must be decided by a match and not a tournament’. Even that principle was to be abandoned in the late 1940s. Nobody in 1937 could have imagined that, after that year’s return contest between Euwe and Alekhine, the next world championship match would not come for over 13 years. The challenger on that occasion, David Bronstein, was barely a teenager at the time of the Stockholm, 1937 rumpus.

Because Nottingham, 1936 was Emanuel Lasker’s last tournament it is sometimes assumed that thereafter he retired from top-level play. In a letter published on page 194 of the May 1969 Chess Life Joseph Platz commented on Lasker’s absence from AVRO, 1938:

‘It is useless to speculate how the man who was among the top players of the world for 50 years would have fared at the AVRO tournament. Had he been invited, he would have played. Lasker and I were good personal friends and he expressed bitter disappointment that he was not invited.’

(2430)

See also The World Chess Championship by Paul Keres.

Reuben Fine’s personal claims concerning the world championship were discussed in C.N. 10028.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.