Edward Winter

Jan Enevoldsen

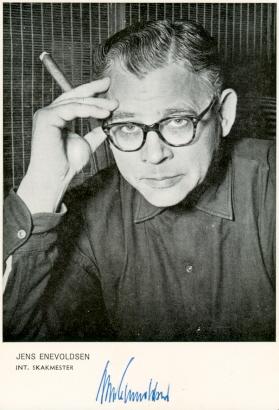

From page 499 of Alt om skak by Bjørn Nielsen (Odense,

1943)

Concerning the blindfold chess exploits of Jens Enevoldsen (1907-80), the following paragraph comes from page 384 of CHESS, 20 July 1939:

‘Jens Enevoldsen of Copenhagen … confirmed his reputation as one of the world’s leading blindfold players by tackling 24 opponents simultaneously at Roskilde and registering, after 11½ hours’ play, 13 wins and 11 draws.’

(2856)

A reference to Jens Enevoldsen’s blindfold play appeared on pages 211-212 of Alt om Skak by Bjørn Nielsen (Odense, 1943), together with this game, probably played in 1936, from a 20-board display (+8 –3 =9):

Jens Enevoldsen – N.N.

Venue?, circa 1936

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 e3 Nbd7 5 cxd5 Nxd5 6 e4 N5f6 7 Nc3 e6 8 e5 Nd5 9 Nxd5 cxd5 10 Bd2 Be7 11 Bd3 O-O 12 h4 f6 13 Bxh7+ Kxh7 14 Ng5+ fxg5 15 Qh5+ Kg8 16 hxg5 Rf5 17 Qh7+ Kf7 18 g6+ Ke8 19 Qxg7 Bf8 20 Qg8 Qe7 21 Rh7 Qd8 22 Qxe6+ Be7

23 Qf7+ Rxf7 24 gxf7+ Kf8 25 Bh6 mate.

From Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark):

‘On pages 180-181 of his 1952 autobiography 30 år ved skakbrættet (“30 years over the board”) Enevoldsen gave the following account of his blindfold chess:

“That year [1933] I gave my first performance, … at the Lyngby Skakklub. It was the first time I had tried this, and I cautiously limited the number of opponents to five. (Of course I had played blindfold chess before. It started as a boy, and I believe I was 14 or 15 years old. My opponent was my younger brother [Harald]. Later, in high school, I sometimes played three games blindfold.) It went all right. I won three, lost one and drew one. Then things started to heat up. Next time, I increased the number of games to eight. That was in Helsingør. Result: +4 –1 =3. Rather quickly I reached 12 games, all of which I won. After that I went out on a tour. It was Alex Villadsen who was responsible for the arrangements. I remember that I arrived in Ålborg and was told that I would be facing 20 opponents. Deep inside I was horrified, but I calmed down and carried out the performance with a score of +8 –3 =9.

In the ensuing years I gave so many performances that I have given up keeping count. Once I scored only 50%. It was in Odense. In the room next door there was a dance school, so I could not concentrate. In due course I became quite experienced, and performances of, for example, ten games are purely routine for me and do not bother me whatsoever. It becomes a little difficult when we arrive at 18 to 20 games, but carrying out the task is only a matter of time, energy and proper playing conditions. Of course, I have often thought of making a new world record, which was then 34 games, set by Koltanowski in Scotland. I steadily worked on it, but the Second World War put an end to it. The highest number I ever played was 24 games in Roskilde in 1939. I won 13 and drew 11. No losses. Now, many years later, I am a little annoyed that I did not take the bull by the horns and allow 12 more opponents in the event. It would then have been a world record.”

The April 1939 Skakbladet (page 73) gave only a brief note on the event in Roskilde, stating that it was played on 12 March 1939 and lasted 11 hours 40 minutes. Twenty-four opponents was a Nordic record.’

(2861)

Per Skjoldager has now tracked down some details of Enevoldsen’s large blindfold display, in the local newspaper Roskilde Tidende of 14 March 1939, page 8. A summary is given below:

14.00: Jens Enevoldsen, his second (Harald Enevoldsen) and the 24 opponents were welcomed to the Hotel Prinsen by the chairman, N.H. Ilsøe. J.E. had the white pieces in all games, and alternately opened with 1 e4 and 1 d4. The openings most used were the Queen’s Gambit, the Ruy López and the Scotch Game.

18.00: Dinner break. J.E. still felt confident of setting a new [Nordic] record.

19.00: Resumption of play.

21.30: J.E.’s first win.

00.00: The single player’s score stood at four games won and eight games drawn.

02.40: He defeated his last opponent after a fine endgame and received applause lasting for over a minute. (Final score: +13 –0 =11.)

The following game from the séance appeared in Roskilde Tidende, 21 March 1939, page 10:

Jens Enevoldsen – Rudolf Christensen

Roskilde, 12 March 1939

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O b5 6 Bb3 d6 7 c3 Be7 8 d4 exd4 9 cxd4 Bg4 10 Be3 O-O 11 a4 Na5 12 Bc2 Nc4 13 Bc1 c5 14 axb5 axb5 15 Rxa8 Qxa8 16 b3 Nb6 17 dxc5 dxc5 18 e5 Bxf3 19 gxf3 Nh5 20 f4 g6 21 f5 Rd8 22 Qe2 Rd4 23 e6 Qd5 24 Nc3 Qc6 25 Be4 Qd6 26 Nxb5 Nf4 27 Bxf4 Qxf4 28 exf7+ Kxf7 29 Nxd4 cxd4 30 fxg6+ hxg6 31 Qf3 Resigns.

Claes Løfgren (Randers, Denmark) quotes from Roskilde Skakklub 1908-1983, a pamphlet published by the Roskilde Chess Club to commemorate its 75th anniversary and written by a number of club members:

‘... Enevoldsen’s final result – after 12 hours and 15 big cigars – was 13 wins and 11 draws: 18½ points out of 24. Quite fantastic, although in justice it must be added that Enevoldsen ought to have lost a game or two. On a couple of occasions, when he was about to leave a piece en prise, his brother Harald suffered momentary spells of deafness and had to ask again if he had really got the move right. But even with a couple of losses, the result, of course, would have been formidable.

No event in the history of the club has sparked nearly the same interest with the press and the public. Even the radio news carried a feature. All day and until the show ended at about 3 a.m. the house was full, and animated discussions took place in the adjoining restaurant. A well-known banker loudly declared that from a chess point of view the whole business was a hoax. The two brothers were simply in telepathic contact with each other – so the existence of this phenomenon was hereby proved.’

Mr Løfgren mentions that although no games from that occasion were given, the pamphlet published one from an earlier visit, when Enevoldsen had played ten opponents blindfold (+7 –1 =2):

Jens Enevoldsen – L. Lind

Roskilde, 21 April 1936

Bololjubow-Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 Bb4+ 4 Bd2 Qe7 5 g3 Ne4 6 Bg2 f5 7 O-O O-O 8 Bc1 c6 9 a3 Bd6 10 Nbd2 Nf6 11 Ne5 Bc7 12 e4 d6 13 Nd3 e5 14 dxe5 dxe5 15 f4 exf4 16 e5 Bxe5 17 Nf3 Bc7 18 Nxf4 Qc5+ 19 Kh1 Bxf4 20 Bxf4 Ne4 21 Ng5 Nf2+ 22 Rxf2 Qxf2

23 Bd5+ and Enevoldsen announced mate.

(2869)

Eliot Hearst (Tucson, AZ, USA) informs us that the extensive volume on blindfold chess (including historical and psychological aspects) that he is writing jointly with John Knott is nearing completion, and here he raises two questions:

‘Firstly, we know that J.O. Hansen broke Enevoldsen’s 1939 Nordic record of 24 simultaneous blindfold games by playing 25 on 24 May 1986. Moreover, John Knott was informed by a Danish chess contact in October 2002 that O.B. Larsen of Denmark had surpassed Hansen’s record by playing 28 games. Can anyone validate this new record and indicate when and where it occurred? We should also like to find out more about the tournament and blindfold career of O.B. Larsen.

Secondly, a few years before his death in 1983, Janos Flesch claimed in a written statement to John Knott that his 52-board blindfold display in Budapest in 1960 had been “duly ratified by FIDE as the new world record”? Can a FIDE official or other chess authority/historian tell us whether this claim is true and, if so, what other simultaneous blindfold records have been “ratified by FIDE”?’

(3329)

Jan Enevoldsen

Following press reports that Nimzowitsch had issued a world championship challenge, Capablanca wrote to him from New York on 21 September 1926 that he had received no direct word and giving him until the end of the year to post a forfeit for a match, failing which he would take up Alekhine’s challenge. (See pages 193-194 of our book on the Cuban.)

From Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark):

‘Nimzowitsch, for his part, was very proud of being recognized as a challenger for the world championship and when he returned from Germany he wrote the following in the Danish chess magazine Skakbladet (January 1927, page 3):

“En særlig glæde var det for mig, at pressen overalt betragtede mig som kandidat til verdensmesterskabet.’ (“It was particularly pleasing that the press regarded me everywhere as candidate for the world championship.”)

On page 48 of his (1966) book Verdens bedste skak Jens Enevoldsen (who appears to have known Nimzowitsch better than Hage did) wrote:

“Det er kendt at Nimzowitsch udfordrede Capablanca til en match om verdensmesterskabet og også fik et høfligt svar fra ham, men ingen andre end Nimzowitsch tog det alvorligt. Trods sin storhed var han ikke manden. Men resten af sit liv medførte Nimzowitsch et visitkort hvorpå der stod: Kandidat til verdensmesterskabet i skak.” (“It is known that Nimzowitsch challenged Capablanca to a world championship title match and also received a polite answer from him, but nobody except Nimzowitsch took it seriously. Despite his greatness, he was not the man. But for the rest of his life Nimzowitsch carried a business card on which was printed World chess championship candidate.”)

Enevoldsen repeated this on page 103 in a slightly different wording.

On page 67 of his (1969) book Træk af Kampklubbens historie E. Verner Nielsen (who also knew Nimzowitsch well) wrote:

“Niemzowitsch var lidt forfængelig; på hans visitkort kunne man således nede i det ene hjørne læse: Skakverdensmesterskabsaspirant.” (“Niemzowitsch was a little vain; on his business card could be read in one of the corners: World chess championship candidate.”)

I have never seen Nimzowitsch use the title “Crown Prince”, but it seems likely that others have done so. At least his good friend and admirer Hemmer-Hansen wrote the following under the heading “Crown Prince of the Chess World” in Jyllands-Posten on 8 October 1933:

“Nimzowitsch regnes nu for skakverdenens ‘kronprins’, og man venter med spænding kampen mellem ham og Aljechin om verdensmesterskabet.” (“Nimzowitsch is now regarded as the ‘Crown Prince’ of the chess world, and we anxiously await the battle for the world championship between him and Alekhine.”)”

It therefore seems that a) the business card dates from 1926, when Nimzowitsch challenged Capablanca, b) the “Crown Prince” title originated at the beginning of the 1930s, and c) it would be wrong to use the title “Crown Prince” in conjunction with the anecdote about the business card.’

(3323)

For further details see Nimzowitsch the ‘Crown Prince’.

Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) has sent us a photograph taken by him of the Nimzowitsch-Enevoldsen ‘double grave’ in Copenhagen:

(4307)

Phil Bourke (Blayney, NSW, Australia) asks why the two masters share the same resting place.

The matter was discussed on page 11 of Schaakgraven (the booklet mentioned in C.N. 4452). That publication relates that Nimzowitsch described Enevoldsen as ‘the hope of Danish chess’ after losing to him in the Copenhagen, 1933 tournament. Enevoldsen died in 1980, and in his will he expressed a wish to be buried alongside Nimzowitsch. The Danish Chess Union, the owner of the plot, acceded.

Per Skjoldager informs us:

‘Enevoldsen’s obituary by Poul Hage in Skakbladet, July 1980, pages 99-102 does not mention the matter, but I have checked the facts with Steen Juul Mortensen, who was the President of the Danish Chess Union in 1980. He confirms that Enevoldsen wanted to be buried alongside Nimzowitsch. His family made a contribution to the fund.

Nimzowitsch, for his part, had no family in Denmark when he died, in 1935. A number of chess friends created a fund to care for his grave, and the fund still exists today, administered by the Danish Chess Union.

As noted by Hage in the above-mentioned obituary in Skakbladet, Enevoldsen was a great admirer of Nimzowitsch, and they became friends in 1933. On page 150 of his autobiography 30 år ved skakbrættet (Copenhagen, 1952) Enevoldsen wrote about his victory over Nimzowitsch at Copenhagen, 1933 (my translation from the Danish):

“As you can imagine, the waves rose high when Nimzowitsch turned over his king. The master removed his glasses and wiped away the perspiration from his brow, stood up and disappeared. From all sides people shook hands with me and slapped me on the back. My elderly mother, who was a spectator that particular day, was as moved as when she became a grandmother ...

A few minutes later Nimzowitsch came back as calm and composed as would be expected. As a good sportsman he offered me his hand and thanked me for the game.

From that day on, he had tremendous respect for my play and never again regarded me with the usual lack of interest. In fact, we began to appreciate each other. Unfortunately, this lasted for only the two years that he had still to live. I am sure that he would have been happy to see the many games that I have played since then in his spirit and in accordance with his principles.”’

(From our collection.)

(5776)

See too Graves of Chess Masters.

Latest update: 20 March 2025.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.