Edward Winter

A miscellany of Chess Notes items about 1 c4.

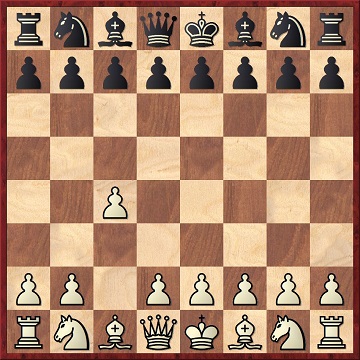

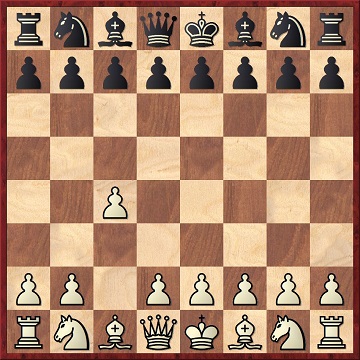

Annotating a game in the October 1904 issue of the BCM (page 406), Blackburne says of his first move, 1 c4:

‘I play this move not that I like it, but because my opponent likes it less.’

(183)

Edward Janusz (Bricktown, NJ, USA) draws attention to a comment by Blackburne on page 122 of his games collection:

‘The English was once looked upon as sound but is now practically discarded.’

Our correspondent adds that ‘English Opening’ at the time may have meant just the move 1 c4 (even with transpositions into various Queen’s Pawn openings), and not an ‘actual system’.

(1320)

The book catalogues prepared by Dale Brandreth are of enthralling interest, crammed as they are with acute observations on the titles listed. For example:

‘The Chess Wheel, V. Armen, English Opening. Similar to the circular slide rule. 65 variations. More a novelty than anything else. Rather humorous in that the author has boldly printed on the device that “patent pending for all chess openings and defenses on the wheel system”. What sublime effrontery and ignorance. Did he invent all these lines? No, of course not. Yet he has the gall to try to patent them. The chess world does not lack its buffoons either.’

(472)

John Donaldson (Seattle, WA, USA) sends an English translation by R. Tekel and M. Shibut of an interesting article by Réti ‘Do “New Ideas” Stand Up in Practice?’, published on pages 8-10 of the Virginia Chess Newsletter of September/October 1993.

A sidelight is Réti’s nomination for White’s best first move: 1 c4. His reasoning begins: ‘One would expect Black’s strongest point in the centre to be d5 since, unlike e5, it has natural protection by the queen. Therefore, the ideal initial move is 1 c4, immediately taking aim at d5.’

Tartakower (see page 15 of his first volume of Best Games) called 1 c4 ‘the strongest initial move in the world’.

(2030)

We first mentioned that remark of Tartakower’s in C.N. 1219.

Numerous books assert that Carl Carls always played 1 c4, except on the occasion when his c-pawn was glued to the board. In fact, games in which Carls opened as White with another first move may even be found in the monograph Carl Carls und die “Bremer Partie” by Kurt Richter (Berlin, 1957).

Annotating the move 1 c4, as played in a match-game between Carls and Antze at Bremen in 1933, Tartakower declared (on page 637 of the August-September 1934 issue of L’Echiquier):

‘An opening which the master from Bremen has been playing, almost without exception, for about 30 years.

Just recently, however, I learned that in annotating the game Eliskases v L. Steiner, which Black won prettily ..., the German master and journalist Leonhardt expressed his joy that this tortuous opening, which comes from the Eastern Jews (“Ost-Juden”) Nimzowitsch and Tartakower, will lose some of its worth.

With such remarks, Leonhardt is certainly doing his homeland a disservice. His hope of flattering official circles may well backfire and he may well be “corrected” for publishing assertions which are:

1. untrue, since the opening was introduced by the Englishman Staunton;

2. maladroit, since the system was developed by the German Carls;

3. ridiculous, since in the game in question, Eliskases v L. Steiner, the move 1 c4 was played by a good Tyrolean, whereas it was refuted by a Semitic player;

4. preposterous, since in chess we take pleasure in seeking truth, without players’ personalities playing any role;

5. unhealthy, since in chess we prefer to be rid of political, ethnological, etc. discussions; and finally;

6. harmful, since the German authorities recommend their citizens not to make attacks on foreigners.’

Leonhardt died a few months later, a great loss to German chess.

(Kingpin, 1996)

A footnote on page 156 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves mentioned that we had been unable to find Leonhardt’s original annotations.

C.N. 6113 added the following from page 4 of Relax with Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1948):

‘The story goes that a practical joker, taking advantage of Akiba Rubinstein’s predilection for 1 P-Q4, once nailed down the grandmaster’s queen’s pawn.’

Annotating his victory (as White) over Schlechter at Vienna, 1907 in his first Best Games volume (pages 15-17), Tartakower gave 1 c4 an exclamation mark and wrote:

‘A curious point: 18 years later (in 1925) I published a detailed analysis of this opening, in which I arrived at the conclusion that 1 P-QB4 was “the strongest initial move in the world” – and I was already applying it intuitively with great predilection in the first stages of my chess career.’

In his notes to Alekhine v Sämisch, Baden-Baden, 1925 on pages 106-108 of La Stratégie, May 1925, Tartakower wrote:

‘1 P4FD. “Le début le plus fort du monde!”, comme je l’ai déjà et maintes fois proclamé. Les Blancs se préparent à bouleverser le centre ennemi sans se créer quelque point faible.’

(7718)

Wanted: instances during Howard Staunton’s lifetime of 1 c4 being called the English Opening on the basis of his espousal of the move.

(9166)

A note by Potter and Steinitz concerning 1 c4:

‘This move, when made by the first player, constitutes what is called the “English Opening”. It is calculated to bring about positions in which each side is soon thrown upon its own resources; but, if met by a proper defence, it is doubtful whether the first player should gain any advantage by its adoption.’

Sources: page 375 of the 18 April 1874 edition of The Field and page 89 of the May 1874 issue of the City of London Chess Magazine.

C.N. 9166 asked for instances during Howard Staunton’s lifetime of 1 c4 being called the English Opening on the basis of his espousal of the move. None having yet been found, we give below a slightly later citation. It is a note by G. Reichhelm about 1 c4 in a Delmar v Brewer correspondence game on page 362 of the American Chess Journal, June 1879 (annotations reproduced from page 4 of the Hartford Weekly Times, 19 June 1879):

‘Now justly called “the English opening”, it having been introduced by the great English champion, Staunton.’

(10066)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.