Edward Winter

A selection of Chess Notes items concerning Max Euwe, with our usual emphasis on less well-known matters.

***

According to Golombek’s Encyclopedia of Chess (page 126 of the 1977 hardback edition), Bad Nauheim, 1937 ‘was the only tournament of importance Euwe won outright in his whole career’.

(32)

C.N. 51 noted that Euwe had just died and gave, from the January 1982 issue of Schakend Nederland, his win as Black against R. Moonen, which was believed to be his last recorded game.

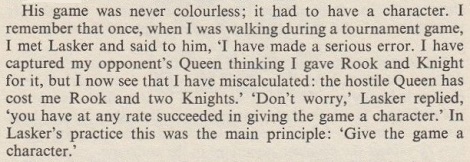

From the fine article by Walter Meiden in the April 1982 Chess Life (page 21) we take the following Euwe quotes:

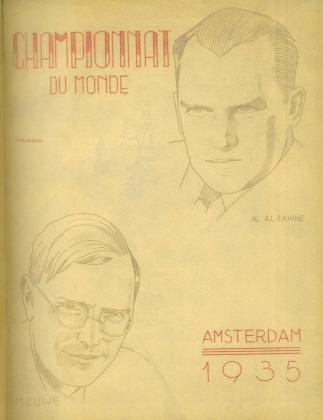

‘Alekhine can see five or six times as much as I can, but I have a plan, and that plan sometimes permits me to win.’

‘Alekhine outplayed me tactically; I outplayed him strategically.’

‘Alekhine should have won the 1935 match; I should have won the 1937 match.’

(497)

An endnote on page 271 of Chess Explorations:

C.N. 551 quoted Botvinnik in the context of Euwe’s death in 1981:

‘The world champions die in the strict order of their succession to the title. Thus the writer of these lines is the next on the list. I telephoned Smyslov and reminded him that after me it would be his turn. Smyslov laughed; indeed, as long as I am alive he can afford to laugh!’

Source: Europe Echecs, April 1983, page 13.

The following year C.N. 820 reported that Petrosian had died, out of sequence. Tal died in 1992 and Botvinnik in 1995.

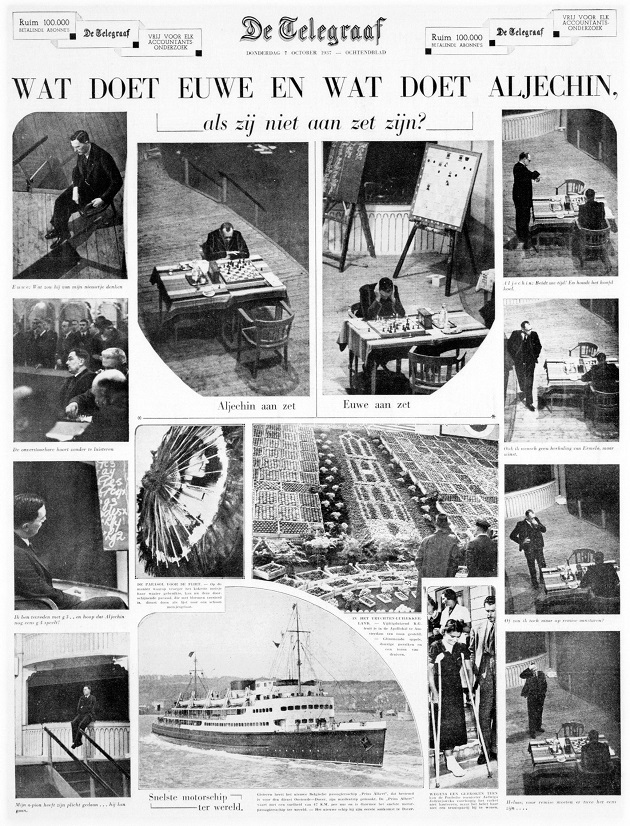

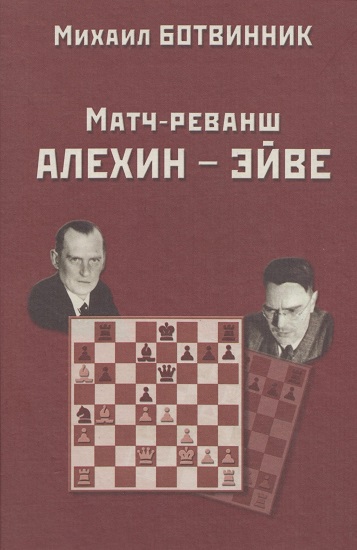

A splendid book is the CHESS volume on the 1937 world championship match with ‘exclusive statements’ by the two players. Here, for instance, is Euwe on Alekhine, from page 75:

‘I must above all marvel at the manner in which he treated the adjourned positions. This is all the easier to judge since I also had to analyse the adjourned games, and thus knew them through and through. When I think of the creative ideas which my opponent sometimes infused into the positions, of the unexpected turns which he was able to discover, then I must express the greatest admiration for his mastery of this phase of the game.’

(770)

See too Euwe and Alekhine on their 1937 Match.

From an interview with Euwe in the September 1981 CHESS (page 200):

[Rubinstein] ‘came to Holland towards the end of the ’30s before his match with Alekhine’.

What match?

Certainly not the same Rubinstein-Alekhine match that BCO wrongly claims took place (page 99) in 1924. In the ‘corrected edition’ the word match has been removed, but the reference is still wrong. The two players never played any match, and had no over-the-board meetings in 1924.

(917)

Thanks to Rob Verhoeven (The Hague, the Netherlands) we can clear up the curious CHESS reference. The September 1981 issue (page 200) quoted Euwe:

[Rubinstein] ‘came to Holland towards the end of the ’30s before his match with Alekhine’.

This was apparently translated from the August 1981 Europe Echecs, page 373:

‘Au début des années trente, avant son match avec Alekhine, il est venu aux Pays-Bas.’

(We wonder in passing how ‘beginning’ became ‘end’.)

But the French, in turn, came from the 5/1981 Schakend Nederland (page 150) which reads:

‘In het begin van de jaren dertig is hij, vóór mijn match met Aljechin, nog in Nederland geweest.’

Of course, no-one should imagine for a single moment that a correction will now emerge from Sutton Coldfield.

(1249)

From one of Dale Brandreth’s recent book lists (Probeg Five):

‘A Guide to Chess Endings by Euwe and Hooper. A superb book by two scholars on the endgame. I still remember Hooper telling me how difficult it was to analyse with Euwe because he was so fast. I find that interesting because it has been intimated by some that Euwe was one of the weakest world champions – something I always felt was perhaps more an indication of the jealousy of those who said it than of any substance. He was, after all, the only man ever to win a major match against Alekhine and, in fact, his overall life score vs Alekhine in tournaments and in their three matches has to be something that few others could aspire to.’

We remarked to Dr Brandreth that we tended to feel that Euwe was one of the weakest world champions, particularly on account of his self-acknowledged tendency to blunder, but that we were not sure those who said so were motivated by jealousy. At his best Euwe was magnificent, but the best did not really last long. Our view was that he had to be put well below Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine, even in terms of their over-the-board clashes, where Euwe had a substantial age advantage over all three. Dr Brandreth’s reply is quoted in full below:

‘I must agree with you in part, but in comparing records, etc. in any competition there is one factor which is difficult to account for, and that is the age at which the player made his record. For example, in the case of Euwe, in my view he probably peaked in the period 1938-1945, but owing to the war he was deprived of the benefits of being able to rack up tournament victories then. As I see it, in the period 1933-39 no one player stood head and shoulders over the rest. AVRO 1938 was not too convincing to me, considering the adverse conditions for the older players (as Alekhine himself said) with the constant travel. Flohr was a disaster at AVRO yet came back to win at Kemeri-Riga 1939 and at Leningrad-Moscow 1939, where he was ahead of Reshevsky (2nd) and way ahead of Keres (12/13th).

Many players such as Fine and Reshevsky did well, but how would they have done in matches vs Alekhine in 1937? It is a fascinating question, but I would put my money on Alekhine by a wide margin vs Fine and by a small margin vs Reshevsky (who would have probably done well on the basis of determination, but whose scant openings knowledge would have been disastrous vs Alekhine). Fine always thought he was top dog in that era, but then he had only one really big success – AVRO – and that was based on two fluke wins vs Alekhine (two draws would have put Keres clear first).

It would be interesting to look at the records of all the leading players in that period (the AVRO eight plus Em. Lasker) to see what conclusions pure results alone lead to. I would extend the period to 1932-39. This takes away Alekhine’s greatest year 1931 on purpose, because the question I am really posing is: on the basis of results in this period does any one player stand out as demonstrating he is more than first among equals? My feeling is that the answer is that it is very close, but that is without making the actual calculations.

Of course, such things as the quality of play are not taken into account. Reshevsky’s record would certainly be no disgrace, but as someone once pointed out to me – and I was surprised at first, but then had to agree – how many great Reshevsky games are there? He is gritty and stubborn, but he lacks the imagination and grand sweep of Alekhine, the grand design of Botvinnik, or the superb strategy of Euwe. Euwe was a great player, but he lacked the killer instinct of Fischer and his tendency to blunder kept his record from being much better. I would agree that he was weaker than Capa, Lasker and Alekhine at their best, but frankly I think the Euwe of 1937 could have handled the Botvinnik of 1948.’

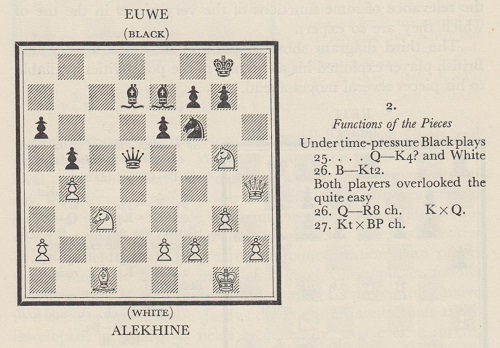

In case anyone has doubts about our statement that Euwe’s tendency to blunder was self-acknowledged, here is a quote from page 253 of that entertaining book Chess Treasury of the Air by Terence Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966):

‘During my chess career, I have made quite a few oversights. In fact, I have probably made more silly blunders than any other world champion.’

(1024)

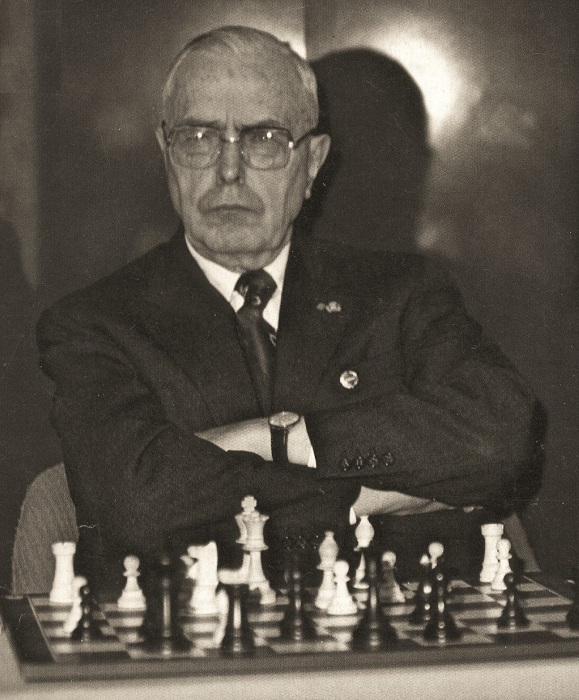

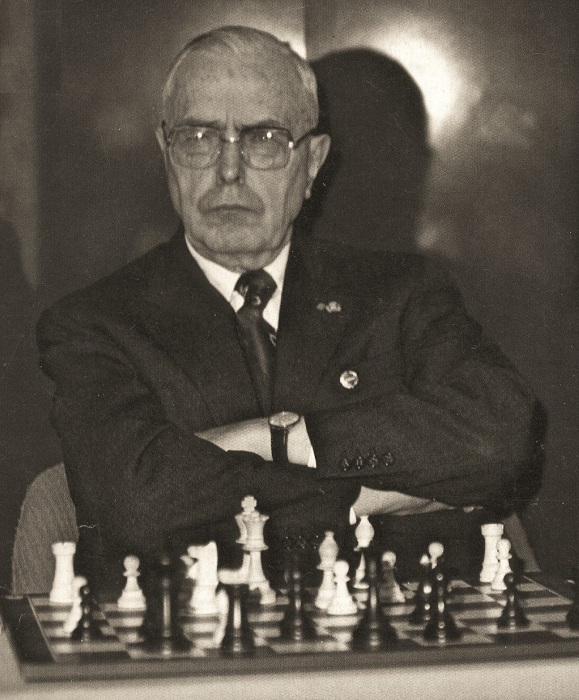

Euwe’s reply (dated 19 May 1970) to W.D. Rubinstein (C.N. 1018, concerning the greatest players of all time) may be noted here: 1 Morphy. 2 Lasker. 3 Fischer. 4 Alekhine. 5 Steinitz. 6 Botvinnik. 7 Capablanca. 8 Tal. 9 Spassky. 10 Euwe. 11 Petrosian. 12 Smyslov.

(1024)

The response by Euwe to W.D. Rubinstein was shown in C.N. 9275:

The earliest Euwe game we have seen:

Jacques Davidson – Max Euwe

Amsterdam, February 1912

French Defence

31...Rd8 32 Nf5 Rd7 33 Kf2 Kf7 34 Ke3 Kg6 35 Ng3 Re7+ 36 Kf2 Rxe1 37 Kxe1 d4 38 Kd2 c5 39 Kd3 b6 40 a4 Kg5 41 Ne2 Kh4 42 Ng1 Kg5 43 Ke4 f5+ 44 Ke5 g6 45 b3 Kh4 46 Kf4 g5+ 47 Kxf5 d3 48 f4 g4 49 h3 d2 50 hxg4 d1(Q) 51 White resigns.

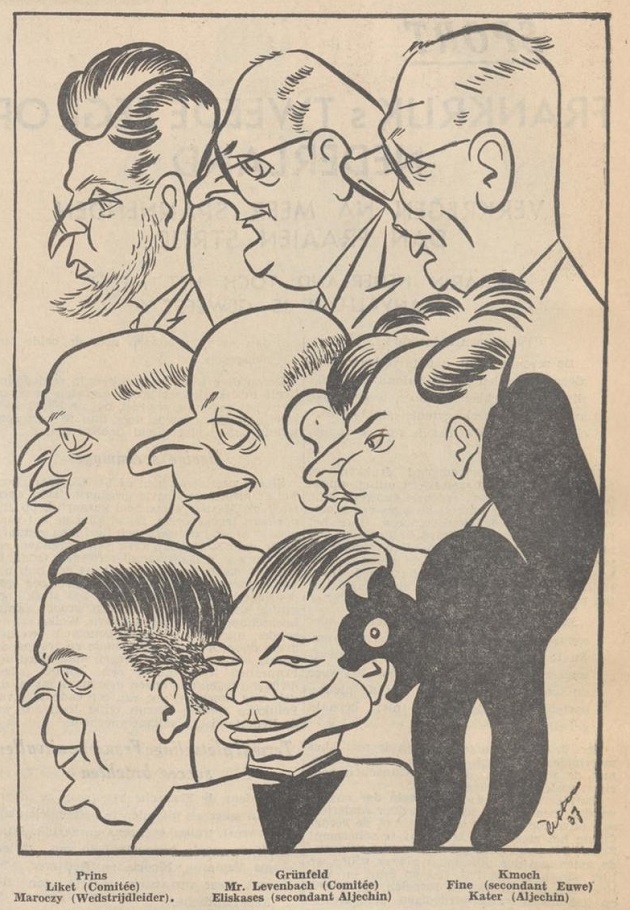

Source: Max Euwe by Hans Kmoch (page 2 of the German edition). This book also gives a study and a two-mover by Euwe dated 1912, and a 1914 victory in a simultaneous exhibition given by Dr J.C. Reeders.

(1811)

An endnote on page 259 of Chess Explorations:

Since White had a straightforward mate in three (with Qxd5+) at moves 25 and 26, it may be wondered whether Black’s 18th move was not the natural ...c6 rather than ...Rac8.

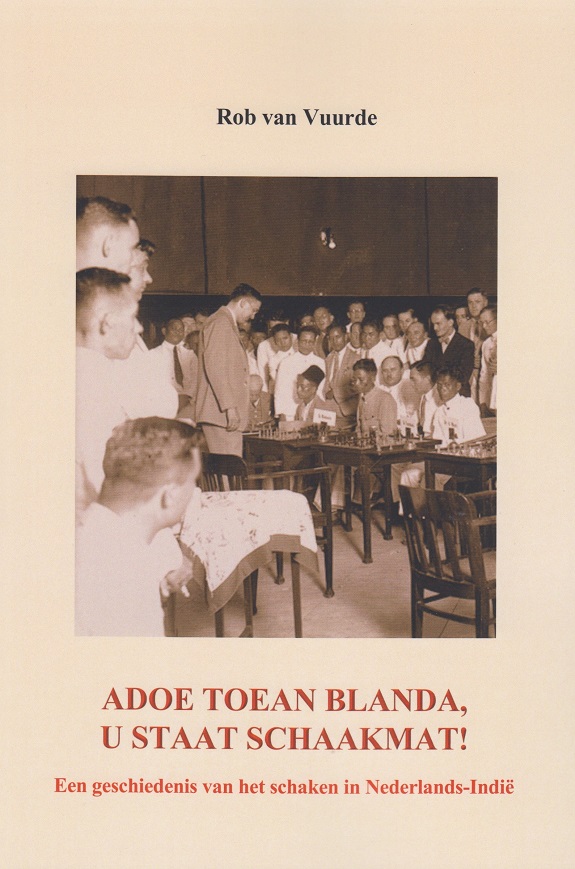

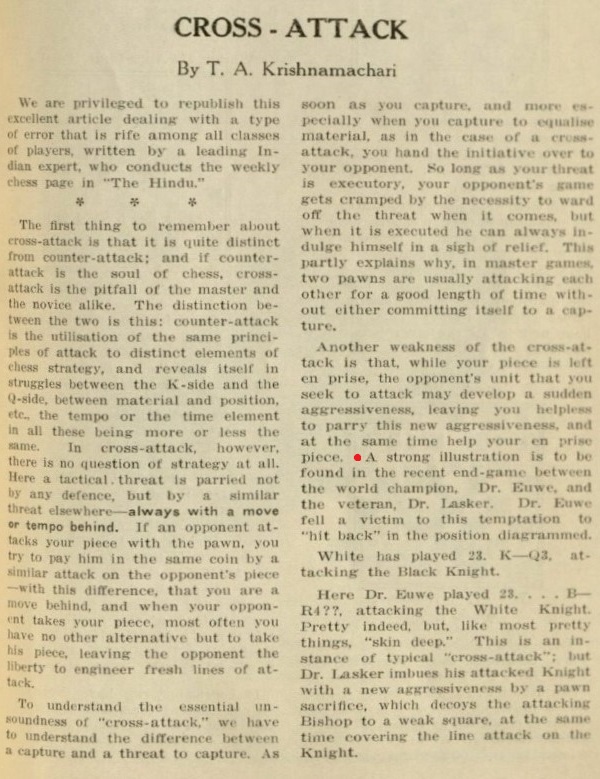

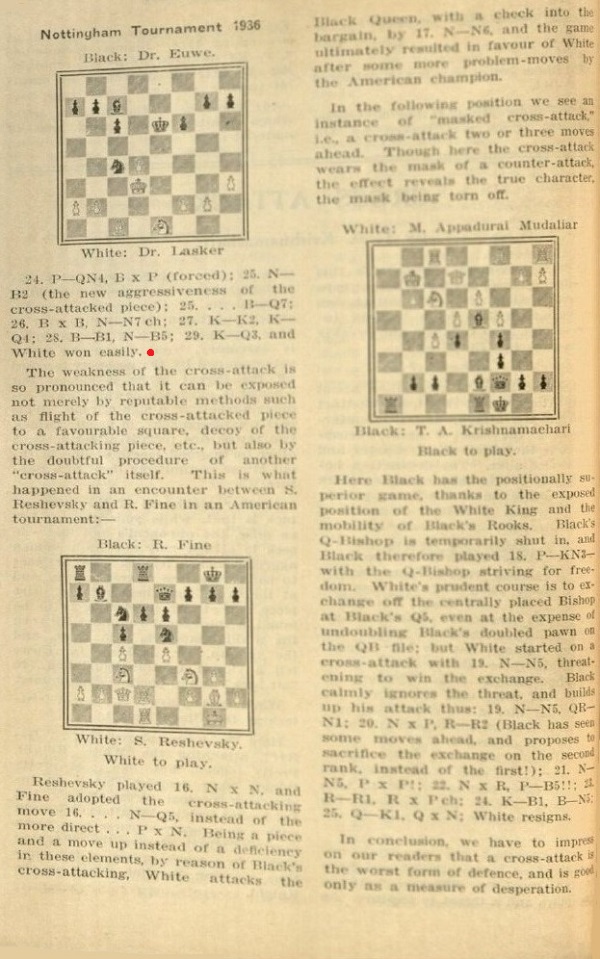

C.N. 1812 reproduced, courtesy of Richard Lappin (Jamaica Plain, MD USA), a 1930 simultaneous game in the Netherlands-Indies in which Euwe (Black) defeated Si Prang. The source (the 12/1930 issue of Schachvärlden) stated that Si Prang could neither read nor write.

In C.N. 1845 Ed Tassinari (Scarsdale, NY, USA) gave Euwe games published in the New York Times, 15 June 1947 (page 5, section 5) against Sussman (King’s Indian Defence) and Evans (Nimzo-Indian Defence). The same item presented the score of a game from a clock exhibition which Euwe lost to Charles Kalme (aged 15) and annotated on page 73 of the March 1955 Chess Review. See too pages 123-124 of A Chess Omnibus.

From Jack O’Keefe (Ann Arbor, MI, USA):

‘After the Manhattan Chess Club International of 1948-49, Euwe visited Detroit for a few days. He stayed at the home of a friend who one evening invited some local players over to meet the former world champion. Euwe graciously agreed to play some casual games with us, one of which was a charming miniature.’

Marvin Palmer – Max Euwe

Detroit, 1949

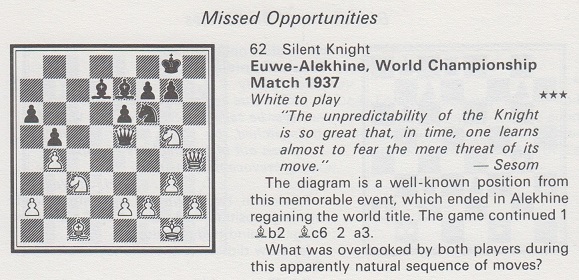

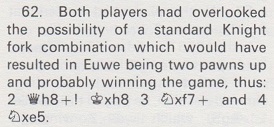

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 a6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Bd3 e5 6 Nb3 Nc6 7 O-O d5 8 exd5 Nxd5 9 Be4 Be6 10 Qf3 Qd7 11 Rd1 Bg4 12 Rxd5 Bxf3 13 Rxd7 Bxe4 14 Rxb7

14…O-O-O 15 White resigns.

A novel example of the familiar trick of queenside castling to win a stray rook at Kt2. Other cases can be found on pages 11-14 of Tim Krabbé’s book Chess Curiosities (London, 1985).

(Kingpin, 1990)

See Castling in Chess.

Apart from the surprising combinational phase, the game below is notable for a rare sortie by the white queen at move six:

M. Euwe – E. Straat

VAS Winter Tourney, Amsterdam, 1922-23

Queen’s Gambit Declined

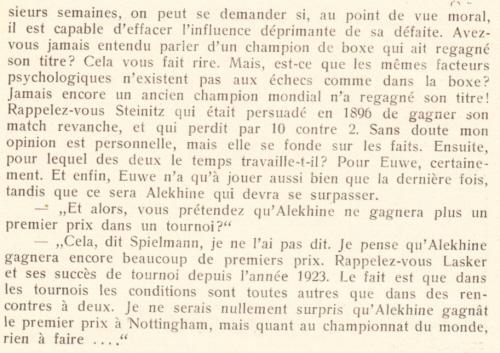

1 c4 Nf6 2 d4 e6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e3 O-O 6 Qf3 Nbd7 7 cxd5 exd5 8 Bd3 c6 9 O-O-O b5 10 h4 b4 11 Nce2 Qa5 12 Kb1 Ba6 13 Bc2 Rfc8 14 Bxf6 Nxf6 15 g4 c5! 16 dxc5 Rxc5! 17 Nd4 Qc7 18 g5 Ne4! 19 g6! Bf6! 20 gxf7+ Qxf7 21 Nge2 Rac8 22 Bb3 Bc4 23 h5 a5 24 Nc1 Ba6! 25 Nd3 Bxd3+ 26 Rxd3 Qc7! 27 a4! bxa3 28 Qxe4 Rc1+ 29 Ka2 axb2 30 Kxb2

30...Qc2+!! 31Ka3 Qxb3+! 32 Nxb3 dxe4 33 Rxc1 Rxc1 34 Nxc1 exd3 35 Nxd3 Drawn.

The exclamation marks are as awarded by Euwe, who annotated the game on pages 127-128 of the May 1923 Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond.

(2024)

Page 285 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves offered a game in which a prominent master (Marshall) overlooked an elementary queen mate at h2. Here is a similar specimen.

Max Euwe – Salo Landau

ASC-NRSV match, 1933

Queen’s Pawn Game

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 e3 d5 4 Bd3 Nbd7 5 Nbd2 c5 6 c3 Bd6 7 O-O Qa5 8 dxc5 Qxc5 9 e4 dxe4 10 Nxe4 Nxe4 11 Bxe4 Nf6 12 Bc2 Bd7 13 Be3 Qc7 14 Bd4 Bc6 15 Qe2 Ng4 16 h3 Nh2 17 Nxh2 Bxh2+ 18 Kh1 Bf4 19 Rfe1 O-O-O 20 b4 Kb8 21 b5 Bd5 22 b6 axb6 23 Rab1 Qc6 24 f3 Bc7 25 Bd3 f6 26 Qf2 Qd6

27 Bxb6 Qh2 mate.

Source: Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond, March 1933, page 79.

It can be imagined how notorious such a game would have become had it been lost by Capablanca.

(Kingpin, 2000)

See too page 313 of A Chess Omnibus.

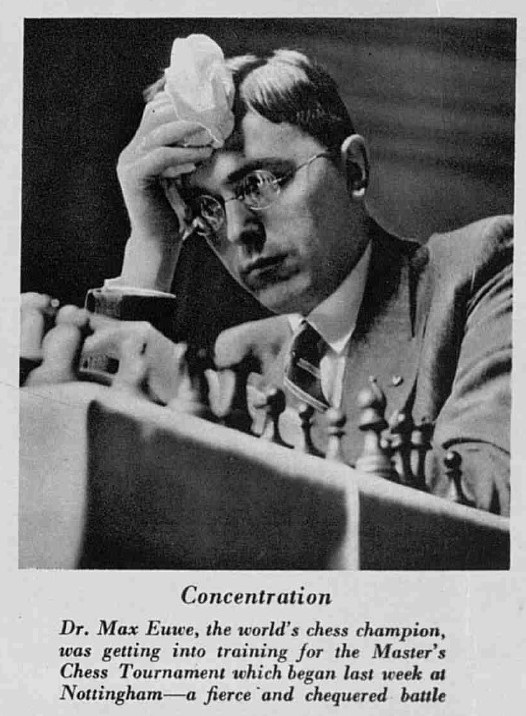

On pages 34-35 of the 14 September 1936 CHESS Euwe annotated his game against Sir George Thomas (White) at Nottingham, 1936. It began: 1 e4 Nf6 2 e5 Nd5 3 d4 d6 4 Nf3 Bg4 5 Be2 c6 6 O-O dxe5 7 Nxe5 Bxe2 8 Qxe2 e6 9 b3

Now Euwe played 9...Nd7 and wrote, ‘Interesting here was 9...Nf4 10 Qe4 Qxd4 11 Qxd4? Ne2+ or 10 Bxf4 Qxd4 attacking both the rook and the bishop. But White plays 10 Qf3! Qxd4 11Qxf4 Qxa1 12 Qxf7+ Kd8 13 Bg5+ and wins’.

On pages 83-84 of the 14 November 1936 issue a reader, H.T. of Hythe, pointed out that Euwe’s ‘interesting’ line loses owing to 10 Bxf4 Qxd4 11 Qd2, and if 11...Qxa1 12 Nc3 Qb2 13 Nc4.

Wanted: other annotational mishaps involving leading players.

(Kingpin, 1997)

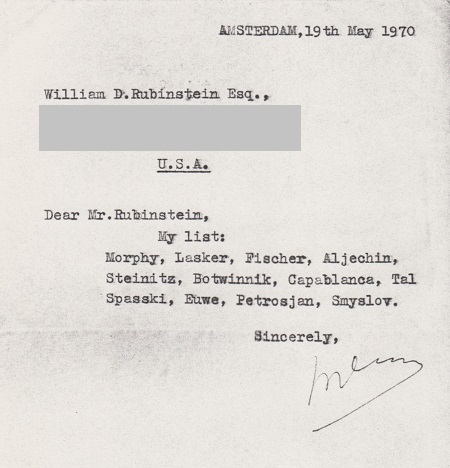

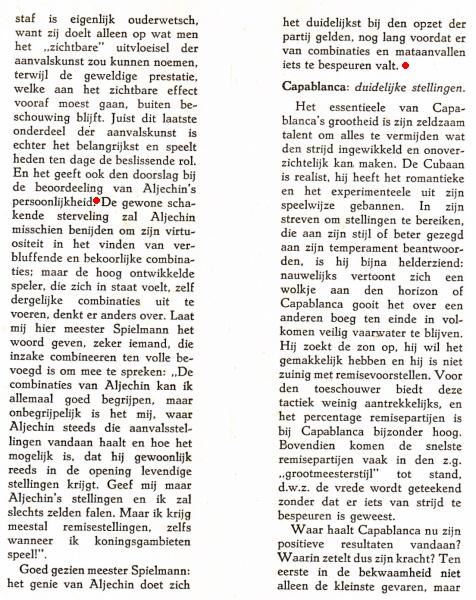

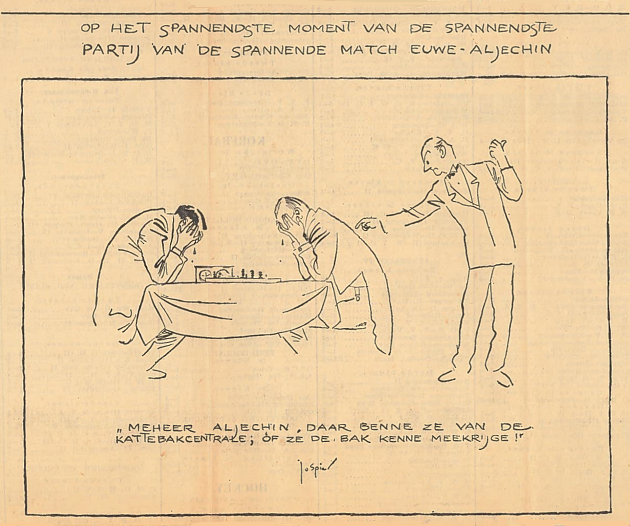

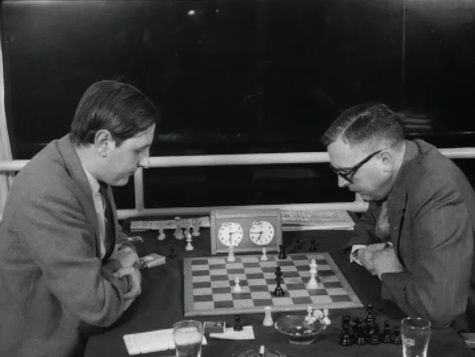

A photograph of Alekhine in play against Euwe at Nottingham, 1936 was given on page 229 of the October 1936 Chess Review:

P.H. Litwinsky was later known as Paul Hugo Little.

‘A fine specimen of Michell’s style’ is the comment about a win over Euwe (Hastings, 1931, 0-1 in 32 moves) on page 85 of R.P. Michell, A Master of British Chess by J. du Mont (published by Pitman in 1947). An odd blunder since, as Owen Hindle, points out to us, the game was won by Euwe, who played Black.

We add a few observations. The game was briefly recounted, though not given, on page 57 of the February 1931 BCM. A number of continental magazines did publish the score (stating that Black won at move 29), an example being the January 1931 Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond (page 17).

The Michell monograph received starkly contrasting notices in the BCM and CHESS. In the former (April 1947, page 114) R.C. Griffith wrote:

‘I doubt whether any five of our British experts of he last quarter of a century could produce such a collection of masterpieces as are here assembled’.

CHESS (April 1947, page 213) believed that:

‘… there must be a hundred British players with better justification for the publication of a book of their games than Michell.’

(Kingpin, 1998)

In an interview with Pal Benko on pages 410-413 of the August 1978 Chess Life & Review, Max Euwe stated that he had only ever composed one chess problem:

Mate in two

Euwe reported that he had composed it ‘when I was travelling, and I made it only because I needed one for my column and I had none with me’.

(Kings, Commoners and Knaves, pages 41-42)

The problem was discussed in C.N.s 78, 147, 224, 253 and 260.

The recent death of D.A. Yanofsky prompts us to record here two remarks by world champions. Firstly, Alekhine’s posthumous book Gran Ajedrez reproduced photographically part of his annotations (in English) to the famous game Yanofsky (aged 14) v Dulanto, Buenos Aires, 1939. At move 22 Alekhine wrote:

‘The whole little game is characteristic of the incisive style of the young Canadian, who was practically the only revelation of the Buenos Aires Team Tournament.’

In the introduction to Yanofsky’s book Chess the Hard Way! (London, 1953) Euwe, for his part, declared:

‘Considering his youth and his talent, I have no doubt that Abe Yanofsky will one day belong to the strongest of the strong ones, and many of my colleagues share this opinion.’

Chess the Hard Way! is, we believe, one of the best autobiographical games collections. Today, alas, it seems all but forgotten, as does Yanofsky’s 1957 treatise on the phase for which he was the most famed, How to Win End-Games.

(2376)

Thomas Broek (Egmond aan Zee, the Netherlands) submits the following game won by Euwe less than a year before he died.

Max Euwe (simultaneous) – Thomas Broek

Egmond-Binnen, 8 February 1981

Benoni Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 c5 3 d5 e6 4 Nc3 exd5 5 cxd5 a6 6 a4 d6 7 Nf3 g6 8 e4 Bg7 9 Be2 Nbd7 10 O-O O-O 11 Nd2 Re8 12 Qc2 Ne5 13 h3 Nh5 14 Bxh5 gxh5 15 Nd1 Ng6 16 Nc4 Qe7 17 Nde3 Nf4 18 f3 Bd4 19 Kh1 Qh4 20 Qf2 Qxf2 21 Rxf2 Re7 22 Nb6 Rb8 23 Nxc8 Rxc8

24 Nf5 Ree8 25 Nxd4 Nd3 26 Nf5 Nxf2+ 27 Kg1 Nd3 28 Nxd6 Red8 29 Nxc8 Rxc8 30 Kf1 c4 31 Ke2 Kg7 32 a5 Kf6 33 Bd2 Ke5 34 Ke3 h4 35 Bc3+ Kd6 36 Kd4 f6 37 Ra4 Nf4 38 Bd2 Ne2+ 39 Ke3 Ng3 40 Be1 Kc5 41 Bxg3 hxg3 42 Kf4 Kb5 43 Ra1 Kb4 44 Kxg3 Kb3 45 f4 Kxb2 46 Re1 c3 47 e5 c2 48 e6 Re8 49 f5 c1Q 50 Rxc1 Kxc1 51 d6 b5 52 d7 Rg8+ 53 Kf3 b4 54 e7 b3 55 d8Q b2 56 Qxg8 b1(Q) 57 Qc4+ Kd2 58 Qd4+ Resigns.

(Kingpin, 2001)

Did Euwe chivalrously grant Alekhine a return match for the world title in 1937? Many authors think so. For example, Richard Eales wrote on page 167 of Chess The History of a Game (London, 1985): ‘But it was only Euwe’s sportsmanship which gave Alekhine the chance to play the match at all.’

Adri Plomp (Hilversum, the Netherlands) sends us a copy of the contract signed on 28 May 1935 between Alekhine, Euwe and the organizing committee for the 1935 match. Article 14 stated:

‘If Dr Euwe wins the match in accordance with Article 4, he is first of all obliged to play a return match against Dr Alekhine if the latter makes such a request within six months of the last game being played. Within a further six months thereafter Dr Alekhine must deposit 2,000 guilders with a bank ... The essential conditions for that match shall be the same as for the match regulated by this agreement, except that the names of Alekhine and Euwe shall be interchanged. It shall be played in Europe at a time acceptable to Dr Euwe, in view of his profession.’

(2473)

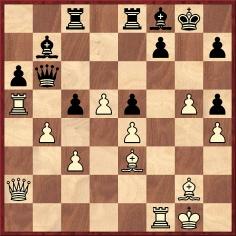

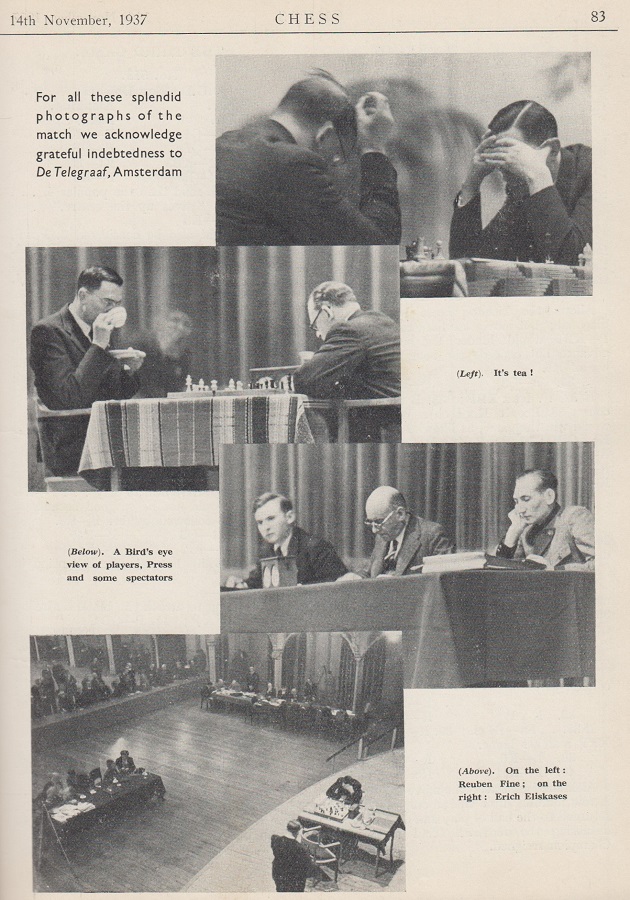

‘Since the last match, the membership of the Dutch Chess Federation has doubled. Euwe gets a “fan mail” of three thousand letters a week, which keeps two secretaries at hard whole-time work.’

CHESS, 14 November 1937, page 78.

(2576)

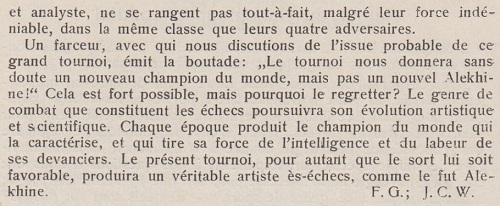

A photograph given in Hans Frank and Chess from the August 1937 issue of Deutsche Schachblätter shows, from left to right, Post, Zander, Frank, Euwe, Miehe and Bogoljubow, under the heading ‘Weltmeister Dr Euwe in Berlin’:

Euwe gave an assessment of Tartakower on pages 106-107 of the April 1956 Chess Review:

‘Tartakower was all action – in gestures and in words. He possessed within him all the good, and perhaps also a few of the bad qualities. He did occasionally appear quarrelsome and once, by overstrictly applying the letter of a regulation, incurred an unsportsmanlike odium. He raised or made up controversies. But, personally, he usually remained in the background, taking sides with one or the other, but without showing partiality to friends. Just as passionately as he at one time championed the interests of “X”, he would next time combat the opinions of that same “X”.

Tartakower had a special word of encouragement for the newcomers who underwent a trying time when their debut fell short of being overwhelmingly convincing. “All of us required a lot of time to learn the game.”

Tartakower was not a “joiner”, and he hated mass demonstrations When the case “Alekhine” came up, following the 1946 London Tournament, Tartakower held aloof. “Everybody now criticizes Alekhine’s anti-semitism. For all that, didn’t we know about it all of 15 years ago?” And Tartakower proceeded to take up a collection for Alekhine who was then in destitute circumstances in Portugal. He signed himself up for a pound sterling. He took up the cudgels for the underdog, but he defended himself personally against those holding the upper hand, also and specifically on the chessboard. A remark such as “Alekhine is unbeatable” could drive him into a rage and provoke him to such a degree that, in his next encounter, he played a class above his own strength, against which the unsuspecting Alekhine could not hold his own.

In the 1922 Pistyan tournament, as Black, he commenced his game with Alekhine in the following defiant fashion: 1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 cxd5 cxd5 5 Nc3 Nc6 6 Bf4 Ne4?! – and won in 31 moves.’

In an interview he gave towards the end of his life, Euwe had the following exchange with Hans Bouwmeester:

‘Euwe: Tartakower was a very interesting man – a paradox. A fine, often trenchant, writer. When, in London in 1946 Alekhine’s collaboration with the Nazis came into question, Tartakower maintained that it was not for us but for the French Government to judge the case. That Alekhine was anti-semitic, we have all known since 1934, he said.

Bouwmeester: Some say that Tartakower was organizing a collection for Alekhine around that time?

Euwe: I recall that – but with Tartakower you never knew whether he was serious or not.’

Euwe also stated: ‘Alekhine may have hoped the Germans would win because he owned several houses in Leningrad. As things went, he lost everything …’

Source: CHESS, September 1981, page 199.

Finally, to return to the Chess Review article, Euwe concluded with a reminiscence about Tartakower at the Hastings, 1945-46 tournament:

‘In every phase he performed the most wonderful feats; for example, winning an endgame of two rooks and two pawns apiece even though his opponent, Denker, had the advantage of a dangerous, passed pawn. “Are you playing to win?”, Denker asked. “The position plays for a win”, Tartakower replied in his peculiar, mystic style. He continued the game and won, unendangered.’

We have asked Arnold Denker whether such an exchange occurred as described, and he has replied to us as follows:

‘It is all correct and the good doctor gave me a lesson I will never forget.’

(2605)

‘Young American shows genius for chess’ was the heading of a full-page article on page 245 of CHESS, 26 May 1956, but the prodigy was not Fischer. ‘Philadelphia has a young player of 16 who is showing every sign of developing into a world champion: Charles Kalme.’

The previous year Kalme had received high praise from Euwe after defeating him in a six-board simultaneous exhibition with clocks. The Dutchman annotated the game on page 73 of Chess Review, March 1955, and few leading players have been so generous in describing the play of a young victor.

Max Euwe – Charles Kalme

Philadelphia, 1955

Grünfeld Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 g3 Bg7 4 Bg2 d5 5 cxd5 Nxd5 6 e4 Nb6 7 Ne2 O-O 8 O-O c6 9 Nbc3 N8d7 10 b3 e5 11 Ba3 Re8 12 d5 Nf8 13 dxc6 bxc6 14 Qc2 Be6 15 Rfd1 Qc8 16 Nc1 Bh3 17 Nd3 h5 18 Bd6 Nh7 19 f3 h4 20 Nf2 Bxg2 21 Kxg2 Ng5 22 gxh4 Ne6 23 Ne2 Nd7 24 Ng4 Nf6 25 Rac1 Nxg4 26 fxg4 Nd4 27 Nxd4 Qxg4+ 28 Kh1 exd4 29 Re1

29…Rad8 30 e5 Qxh4 31 Qxc6 Bh6 32 Rcd1 Bf4 33 Re2 Qh5 34 Rde1 d3 35 Rg2 d2 36 White resigns.

Euwe concluded:

‘A baffling finish. With Black’s last six moves, he has hit the nail right on the head every time.

One indeed asks oneself: how will this young man be playing five years hence? Woe is Moscow!’

Source: Chess Review, March 1955, page 73.

(2630)

For the remainder of this item, giving further information about Kalme, see Chess Jottings.

Charles Kalme

From page 85 of The Pleasures of Chess by Assiac (New York, 1952):

‘If among the living great masters there is one rightly renowned for the precision of his mind and a correspondingly rare victim to oversights or hallucinations, I would say that – next to the great Botvinnik – this master is Max Euwe.’

Euwe himself commented on page 253 of Chess Treasury of the Air by T. Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966):

‘During my chess career, I have made quite a few oversights. In fact, I have probably made more silly blunders than any other world champion.’

(2840)

On pages 410-413 of the August 1978 Chess Life & Review Max Euwe was interviewed by Pal Benko. Here is one exchange, regarding the 1935 world championship match:

‘Benko: I have heard many rumors that Alekhine was drinking heavily during the match and was behaving strangely sometimes. Can you comment?

Euwe: I don’t think he was drinking more then than he usually did. Of course he could drink as much as he wanted: at his hotel it was all free. The owner of the Carlton Hotel, where he stayed, was a member of the Euwe Committee, but it was a natural courtesy to the illustrious guest that he should not be asked to pay for his drinks. I think it helps to drink a little, but not in the long run. I regretted not having drunk at all during the second match with Alekhine. Actually, Alekhine’s walk was not steady because he did not see well but did not like to wear glasses. So many people thought he was drunk because of the way he walked.’

(3005)

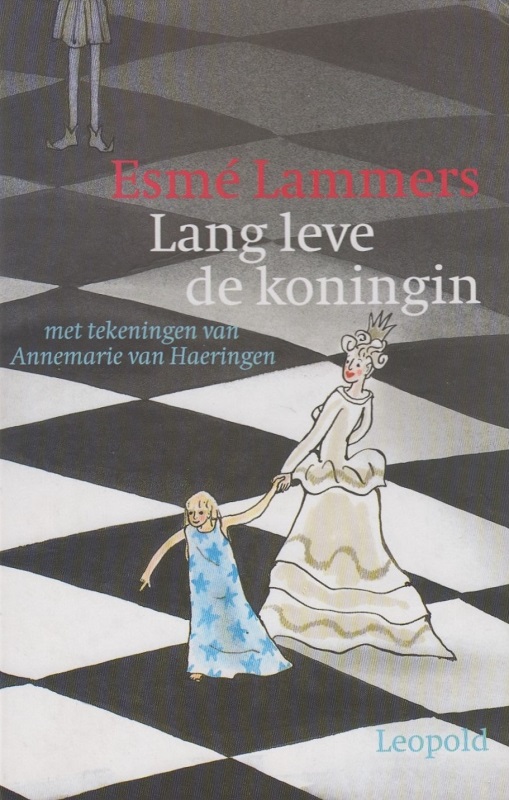

Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) points out a chess novel for children Lang leve de koningin (‘Long Live the Queen’) by Esmé Lammers, who was born on 9 June 1958. Our correspondent adds that in 1995 she directed the film of the same title and, moreover, that she is the grand-daughter of Max Euwe.

(3276)

Question: How many times did Euwe play against Tal?

Answer: Euwe played Tal once only, as he stated when, in an interview shortly before his death, he was asked by Hans Bouwmeester whether he had played against all the world champions apart from Steinitz:

‘I have played them all except Spassky and Karpov. Fischer three times; Tal just once, by radio.’

Source: CHESS, September 1981, page 197.

The game-score and a few details (we should like more) are given at Tim Krabbé’s website.

(3322 & 3331)

From Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA):

‘On page 102 of his book Max Euwe (Alkmaar, 2001) Alexander Münninghoff relates that in 1934 Hans Kmoch successfully persuaded a reluctant Euwe to challenge Alekhine for the world’s championship, as Kmoch felt that “Alekhine’s form was – at least temporarily – in decline”. Münninghoff then makes three separate references to the game Alekhine-Lilienthal from the Hastings, 1933-34 tournament, which Kmoch supposedly saw as emblematic of that decline:

1. “Alekhine’s loss against the young and promising Hungarian Lilienthal was especially revealing in Kmoch’s eyes: for the first time in his career, Alekhine had been outplayed in a series of complicated tactical manoeuvres.”

2. (Münninghoff, paraphrasing Kmoch’s words to Euwe) “Didn’t you see Alekhine’s Hastings games? Don’t you know how he fumbled against Lilienthal?”

3. (Münninghoff, paraphrasing again) “Why don’t you have another look at that game of his against Lilienthal, then you will see that it wasn’t an accidental slip-up.”

I find all this rather perplexing, as Alekhine lost no games at Hastings, 1933-34, and in fact defeated Lilienthal in the game in question. Moreover, a quick check with Fritz indicates that Alekhine never stood worse during the tactical phase of that game; nor did he “fumble” or “slip up”. How Münninghoff can be so mistaken about a game that he himself considers the central topic in a “conversation that would have a decisive impact on the history of chess” is a mystery to me.’

We offer a few comments:

a) The original (1976) Dutch edition of Münninghoff’s book (pages 148-149) had a similar account. Euwe was listed as a co-author (for the annotations) and he also contributed the Foreword.

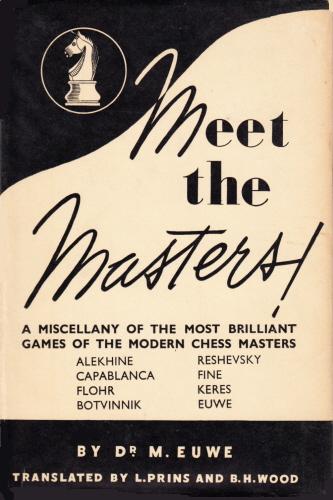

b) Kmoch wrote the chapter on Euwe in the former world champion’s book Zóó schaken zij! (Amsterdam, 1938). On page 151 he noted Alekhine’s relative failure at Hastings, 1933-34 but made no mention of the Lilienthal game. The chapter was expanded for the English edition, i.e. Meet the Masters (London, 1940), but there was still no reference to Lilienthal. To quote from page 258:

‘Then came a break in his chess career through his devoting himself to his mathematical studies for a while. Alekhine’s slight lapse in the Christmas tournament at Hastings, 1933-34 suddenly gave him the idea of challenging the now world champion to another match, and by the summer of 1935 the great event had been arranged.’

c) On page 123 of his monograph Max Euwe (Berlin and Leipzig, 1938) Kmoch stated that one January evening in 1934 he and Euwe were discussing Alekhine’s performance at Hastings (equal second with Lilienthal behind Flohr), and the conversation turned to the fact that Euwe had a 7-7 score against Alekhine in their last 14 games. No other master had put up such resistance against the world champion, and that evening Euwe decided to challenge him for the title. For the record, Kmoch’s original text is reproduced below:

‘Im Januar wohnte ich bei Dr. Euwe. Eines Abends sassen wir beisammen und plauderten über das letzte Weihnachtsturnier in Hastings, wo Flohr den ersten Preis gewann, während Aljechin und Lilienthal die zwei folgenden Preise teilten.

Es bedeutete damals noch eine grosse Sensation, wenn Aljechin einmal nicht Erster wurde, und so kam es, dass sich unser Gespräch bald nur noch um den Weltmeister drehte. Natürlich kamen auch die Ergebnisse der Spiele zwischen Euwe und Aljechin zur Sprache: 7:7 aus den letzten 14 Partien, ein prachtvoller Erfolg für den Holländer. Keinem anderen Meister der Welt ist es geglückt, Aljechin so guten Widerstand zu bieten (welche Feststellung übrigens auch heute noch zutrifft). Und irgendwie kam es, dass Euwe an diesem Abend den Entschluss fasste, Aljechin zum Kampf um die Weltmeisterschaft herauszufordern.’

d) We can supply no explanation for Münninghoff’s statement that Alekhine lost to Lilienthal or for his belief that the game was otherwise significant.

e) Pre-1934 predictions that Euwe had chances of becoming world champion are not too difficult to find. For example, the text below appeared on page 54 of the February 1931 BCM:

‘The popular Dutch champion is still under 30, so he should be a strong candidate for the world championship before long.’

On the other hand, we note the following on page 3 of the January 1936 BCM:

‘Euwe has fulfilled the prophecy of Dr Emanuel Lasker, when he was still a boyish student, that he would one day win the world title.’

When and where did Lasker make such a prediction about Euwe?

(3348)

Max Euwe

Glenn Giffen (Toronto, Canada) and Mark Weeks (Brussels, Belgium) raise the subject of the ‘champion for one day’ claims sometimes seen regarding Euwe, and for readers’ convenience we revert here to C.N. 3321 [see pages 295-296 of Chess Facts and Fables], where Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) wrote:

‘I have repeatedly read that in 1947 Euwe was champion for one day; for instance, page 127 of the second edition of The Oxford Companion to Chess says:

“With the death of Alekhine in 1946 the world championship title was vacant. To deal with the matter FIDE delegates assembled in 1947, and at the same meeting the Soviet Union became a member. The delegates decided that Euwe, as the previous title-holder, and indeed the only ex-champion still alive, should become world champion pending the next contest. The next day the Soviet contingent arrived, having been delayed en route, had the decision annulled, and the title left vacant. Thus he would say wryly that he had been world champion for one day in 1947.”

However, according to the minutes of the FIDE Congress, that decision was never taken. Below is the Spanish version of the two reports on the sessions of 1 and 2 August 1947 respectively, as published in El Ajedrez Argentino, November-December, 1947, pages 298-300):

“La cuestión del Campeonato del mundo se discute y después de votación de diversos proyectos se inclinan los delegados, cuando el Dr. Euwe abandonó la sesión, a la proclamación del mismo como Campeón del mundo con la obligación de jugar un match con Reshevsky y luego el ganador de enfrentarse con Botvinnik. Sres. Louma y Rogard juzgan esta determinación como peligrosa en vista de la ausencia del delegado soviético y proponen aplazar la resolución en espera de la Delegación de la U.R.S.S. Esta proposición fue aceptada.”

“Presentes los mismos Delegados de la sesión anterior y los Delegados soviéticos señores Pochegnikov, Ragozin y Yudovich y el intérprete S. Malolev. (...) Luego se discute la reglamentación del Campeonato del mundo. Se acepta por unanimidad jugar un torneo de seis grandes maestros como fue fijado en la Asamblea General de Winterthur, 1946. El torneo se inicia el 1º de marzo de 1948 en Holanda jugándose allí la mitad del torneo. Después de un intervalo de 15 días como máximum se jugará la segunda mitad del torneo en URSS de modo que el torneo terminará el 31 de mayo de 1948. El torneo se jugará entre los maestros designados y presentes al iniciarlo y en el caso de que no se llevara a cabo decidirá la Asamblea General próxima otro reglamento.”’

In expressing gratitude to Mr Sánchez for these quotes, C.N. 3321 commented that we had been unable to find an English version of the minutes of FIDE’s 1947 Congress (which remains the case today). The first passage above states that after Euwe left the room the delegates decided to proclaim him world champion, but with an obligation upon him to play a match against Reshevsky and with the winner of that match then having to play Botvinnik. However, Messrs Louma and Rogard regarded this proposal as dangerous in view of the absence of the members of the Soviet delegation, and it was decided to postpone the resolution, pending their arrival. The second text above states that after they had come the following day the six-man match-tournament was agreed upon.

C.N. 3321 furthermore requested substantiation (not yet found) for the statement in The Companion that Euwe himself ‘would say wryly that he had been world champion for one day in 1947’ and for the assertion on pages 270-271 of Max Euwe by Alexander Münninghoff (Alkmaar, 2001) that in 1947 ‘Euwe was world champion for two hours’. We also wondered about the identity, and even existence, of the ‘someone’ on page 9 of part two of Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors (London, 2003):

‘Euwe held the crown for only two years (1935-37), and someone once christened him “king for a day”, in view of Alekhine’s indifferent form.’

(3816)

See too Interregnum.

Peter de Jong (De Meern, the Netherlands) sends the following curious game from a simultaneous exhibition:

Max Euwe – N.N.

Brazil, 1947

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nd2 Nc6 4 Ngf3 dxe4 5 Nxe4 Be7 6 c3 Nf6 7 Bd3 O-O 8 O-O Bd7 9 Nfg5 g6 10 Qf3 Kg7 11 Qh3 e5

12 Qh6+ Kxh6 13 Ne6+ g5 14 Bxg5+ Kg6 15 Nxf6+ e4 16 Bxe4 mate.

Source: Euwe’s column in the July 1947 issue of the Dutch magazine De Uitkijk, from a scrapbook in our correspondent’s possession.

Euwe wrote in the column that he spoke no Portuguese but learned three sentences before his tour began. With every exhibition he added an extra line to his speech, and during his last display, in São Luiz do Maranhão, he used his entire collection of sentences, to loud applause. The next day he read a report in the local newspaper that he had thanked the audience in Spanish.

(4014)

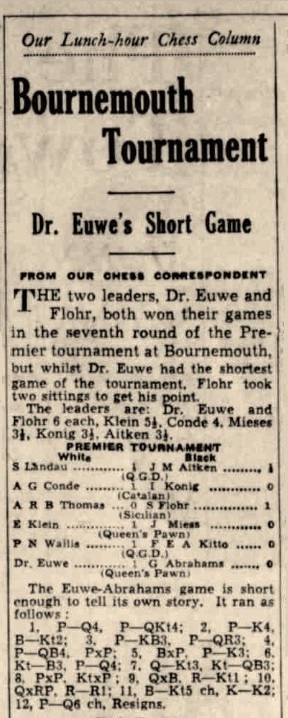

In Bournemouth on 21 August 1939 Gerald Abrahams lost a game (1 d4 b5) in 12 moves against Euwe, as reported at the start of the chess column on page 7 of the (London) Evening News the following day:

See The Chess Moves 1 b4 and 1...b5.

A strange matter from two decades ago (C.N. 1181 – see page 96 of Chess Explorations) is revived here.

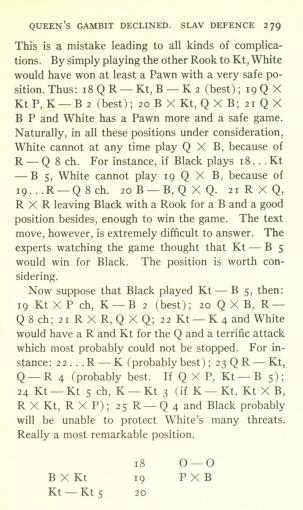

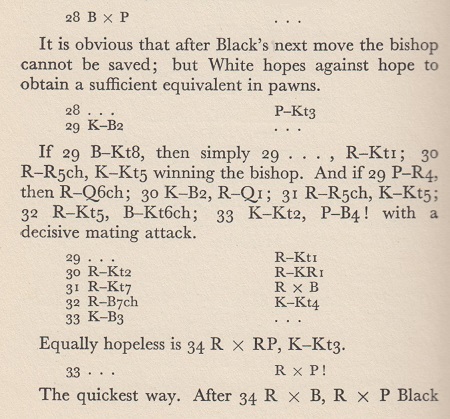

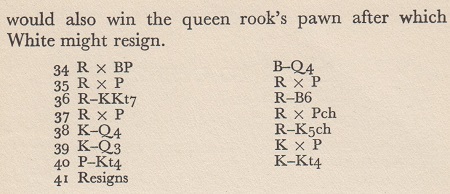

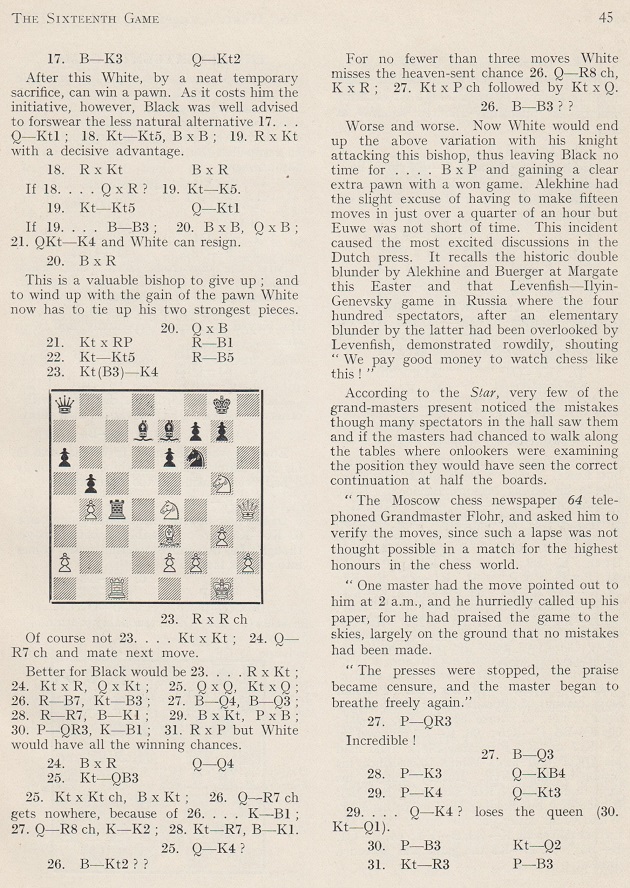

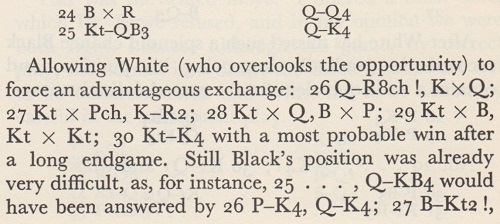

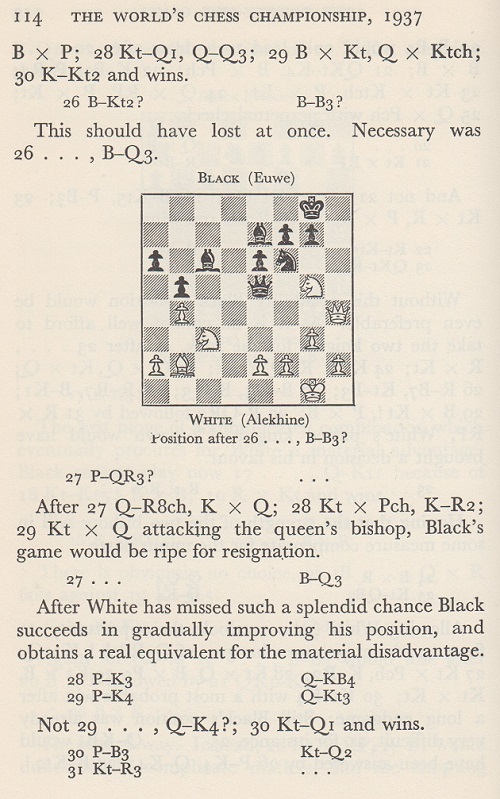

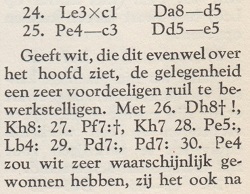

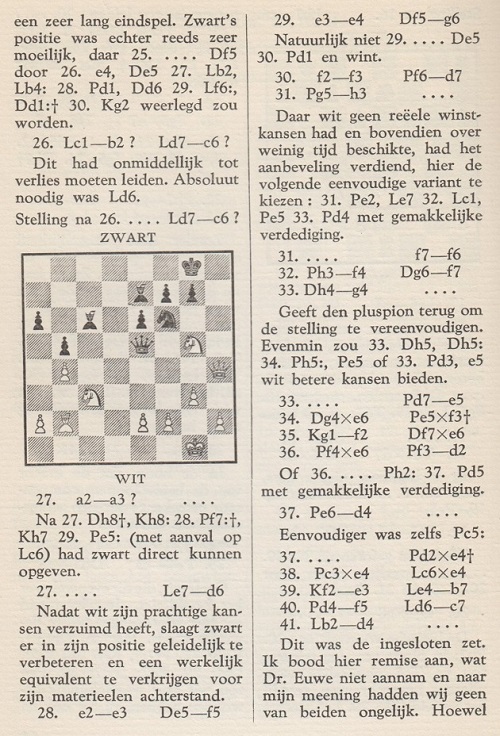

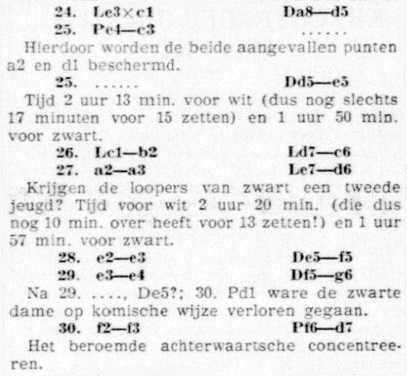

One of Alekhine’s most notable sacrificial experiments was in the sixth game of his 1937 world championship match against Euwe. As White he opened 1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nc3 dxc4 4 e4 e5 5 Bxc4 exd4 6 Nf3 and won quickly after Euwe’s 6...b5? In his notes (My Best Games) Alekhine said that his ‘chief’ variation started 6...dxc3 7 Bxf7+ Ke7 8 Qb3 Nf6, etc., which contradicts Reinfeld’s claim (The Human Side of Chess, page 211) that the ‘greatest gamble of his life’ was played ‘on the spur of the moment’.

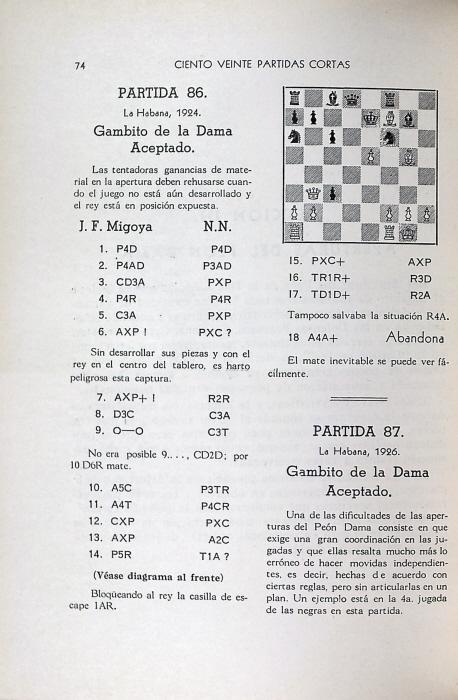

It always seems to have been assumed that Alekhine was the first to play this piece sacrifice, but we found the following game, recorded as having been played 13 years earlier, in 120 Partidas Cortas de Ajedrez by Gumersindo Martínez (Havana, 1947), page 74:

J.F. Migoya – N.N.

Havana, 1924

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nc3 dxc4 4 e4 e5 5 Nf3 exd4

6 Bxc4 dxc3 7 Bxf7+ Ke7 8 Qb3 Nf6 9 O-O Na6 10 Bg5 h6 11 Bh4 g5 12 Nxg5 hxg5 13 Bxg5 Bg7 14 e5 Rf8 15 exf6+ Bxf6 16 Rfe1+ Kd6 17 Rad1+ Kc7 18 Bf4+ Resigns.

Can any further particulars be found?

(4079)

Concerning the sixth match-game against Euwe, 1937 the following remark by Alekhine appeared in his second Best Games collection after 1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nc3 dxc4 4 e4:

‘It is almost incredible that this quite natural move has not been considered by the so-called theoreticians. White obtains now an appreciable advantage in development, no matter what Black replies.’

Following 4...e5 5 Bxc4 exd4 there came 6 Nf3, ‘yet another of Alekhine’s sacrificial hazards, which would hardly bear repetition’ in the words of R.N. Coles on page 77 of Dynamic Chess (London, 1956).

At a library in Havana in 1986 we copied down this score from page 74 of 120 Partidas Cortas de Ajedrez by Gumersindo Martínez (Havana, 1947). Now we are able to show the page, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library:

(8250)

Johan Hut (Baarn, the Netherlands) and Pascal Losekoot (Soest, the Netherlands) report that pages 5-6 of the January 1982 Schakend Nederland stated that Max Euwe was cremated on 1 December 1981 in Driehuis-Westerveld, following a ceremony attended by hundreds of visitors and at least ten speakers. The Dutch magazine made no mention of a permanent memorial.

Our correspondents add, however, that on 7 May 2004 a statue was unveiled on the Max Euweplein in Amsterdam, near the Leidseplein. It was a bronze bust of Euwe, 65 centimetres high, and was created by José Fijnaut of Geverik (Limburg). The unveiling ceremony was performed by a city councillor, Euwe’s daughters and his grand-daughter, Esmé Lammers. (It may be recalled from C.N. 3276 that she is the writer/director of the chess story Lang leve de koningin.)

(4116)

Calle Erlandsson sends four photographs of the Euwe memorial which were taken by him on 27 November 2004:

(4121)

In C.N. 3194 (see pages 280-281 of Chess Facts and Fables) a correspondent mentioned a report in Alexander Münninghoff’s book on Max Euwe (pages 155-156 of the Dutch original and page 112 of the English edition) that in 1935 Euwe played, while preparing to face Alekhine for the world championship, a secret ten-game match against Spielmann. Below is Münninghoff’s text:

‘… just before the final secondary school exams he met Spielmann for a drawing-room match. This latter piece of practical training went quite badly for him; we don’t know whether he found it hard to concentrate because of his schoolwork or whether he had underestimated Spielmann, who was clearly past his prime as a chessplayer, but the fact remains that the peripatetic Austrian veteran claimed this secret ten-game match in fairly superior style with 6-4 (+4 –2 =4).’

Max Euwe

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) quotes three reports from 1935 which show that the existence of the match was not a secret and that, moreover, there is no unanimity as to who won the contest:

1) From page 402 of the September 1935 BCM:

‘In preparation for his match for the world championship, Dr Max Euwe has had a practice match with R. Spielmann, whom he beat by 4-2, with 2 draws.’

2) Pages 282-283 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 15 September 1935 also referred to the Euwe v Spielmann match, without giving the result:

‘Der holländische Vorkämpfer nimmt den Kampf sehr ernst; so hat er sich in Trainingskämpfen mit Spielmann und Eliskases geschult und in Wien theoretische Studien getrieben.’

3) The December 1935 Wiener Schachzeitung had an article reviewing the past year, and on page 354 it was stated that Spielmann had defeated Euwe:

‘... in einem Übungswettkampf schlug er Euwe 4:2 ...’

We can add that in De Groene Amsterdammer (an article reproduced on pages 185-186 of the June 1935 Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond) Salo Landau wrote that Euwe and Spielmann were playing a training match in the absence of the press and witnesses, so that Alekhine would not have the benefit of seeing the games:

‘Het is bekend, dat Euwe op het oogenblik een oefenmatch speelt met Spielmann. Pers noch toeschouwers worden hierbij toegelaten, uit vrees, dat Aljechin de partijen te zien zal krijgen en daardoor het geheim der vorderingen van den Nederlandschen kampioen te weten zou komen.’

Can readers shed further light on the Euwe v Spielmann match?

(4174)

To revive a matter from C.N. 33, on page 60 of Tal Since 1960 (St Leonards on Sea, 1974) W.H. Cozens wrote:

‘... when I remarked to Dr Euwe after the publication of his book From My Games in 1938 that the book would have been even better for the inclusion of a short selection of “Other Games” such as gave such a sparkle to the Alekhine books he said, “I have no ‘other games’”. Botvinnik has a similarly austere attitude.’

Euwe’s reply is not to be taken literally, and we wonder whether readers can submit any little-known sparklers from old publications.

(4510)

From page 176 of the June 1939 issue of the Tijdschrift van den Koninklijken Nederlandschen Schaakbond:

The occasion was the match between Holland and England in the Hague, 28-29 May 1939.

(5116)

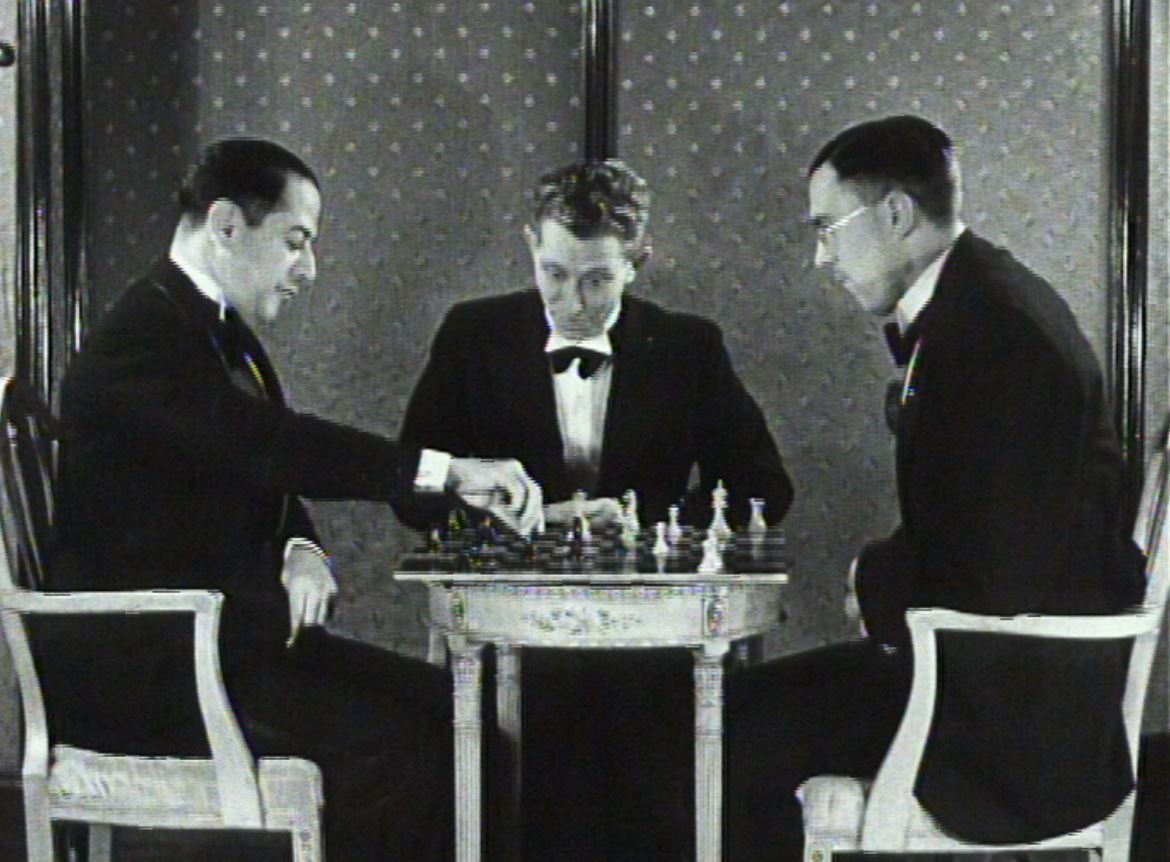

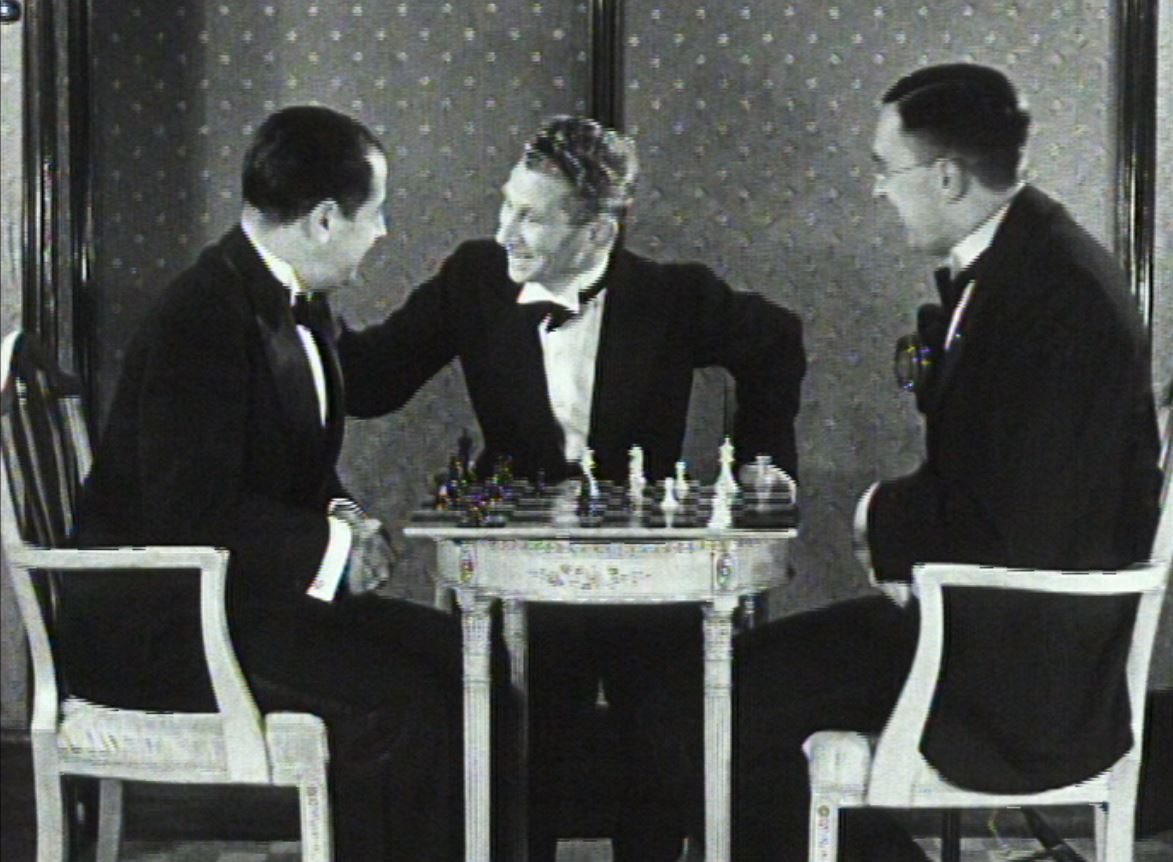

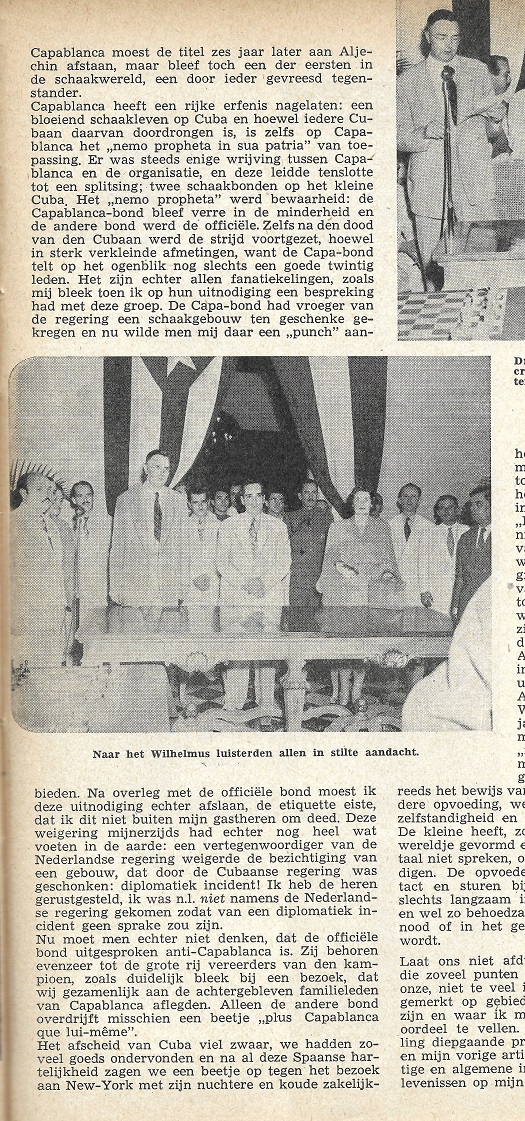

Ryan Paulis (Amsterdam) informs us that much Euwe-related footage is now available on-line, including an unmissable item which features Capablanca speaking.

(6862)

(

Note on 6 December 2019: at present, the best available link appears to be on YouTube.

(7550)

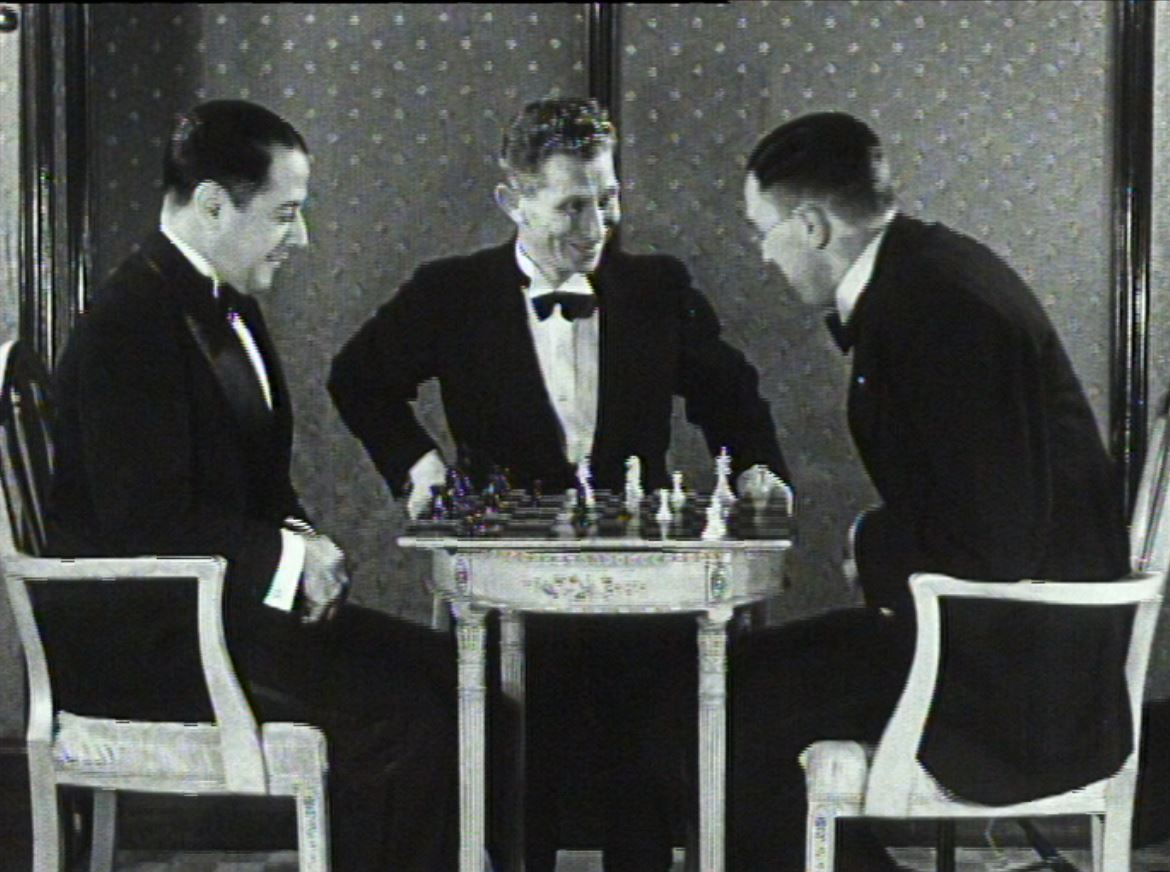

Further to the above items, we are grateful to Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) for these screen-shots of Capablanca and Euwe with Han Hollander (1886-1943)

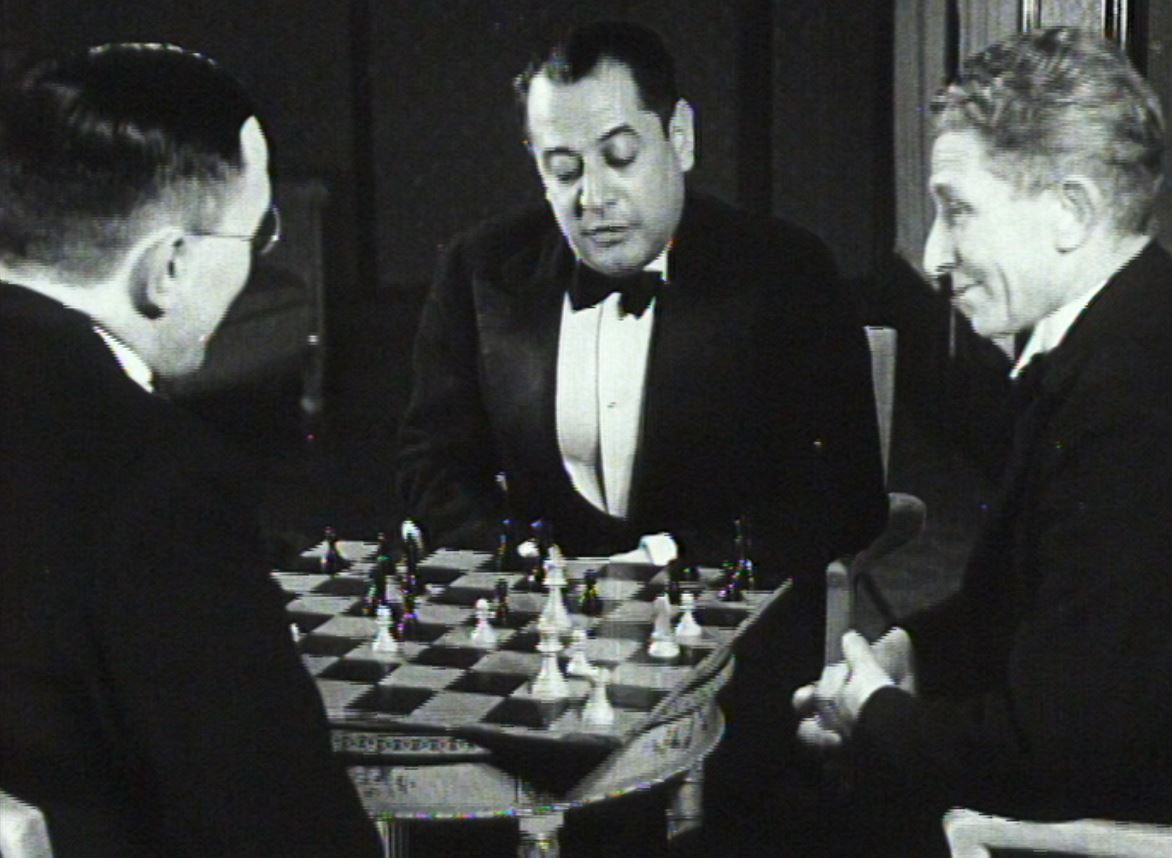

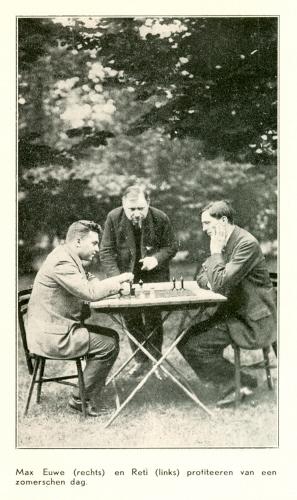

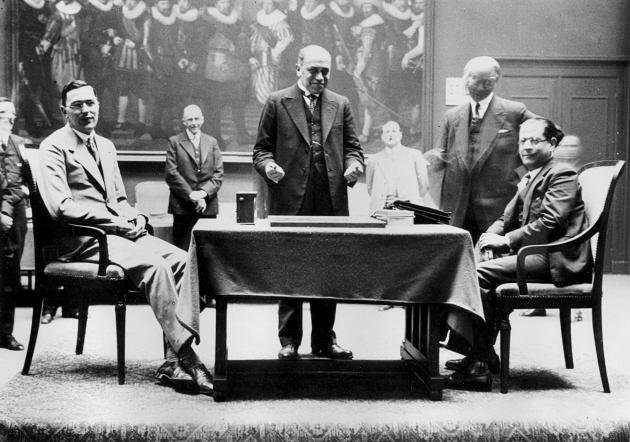

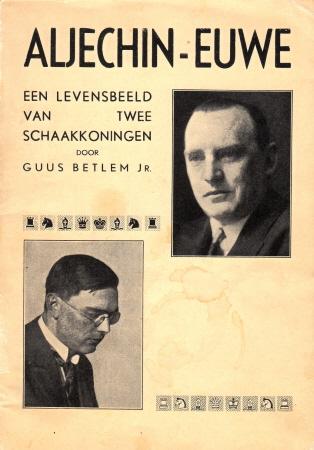

Can any reader identify the third man in this photograph, which comes from Aljechin-Euwe by Guus Betlem Jr (Helmond, 1936)?

(5187)

Peter de Jong suggests – and we believe him to be correct – that the person standing is Willem Schelfhout (1874-1951). Below is a photograph published on page 136 of the February 1951 Tijdschrift van de Koninklijke Nederlandse Schaakbond:

Willem Andreas Theodorus Schelfhout

(5197)

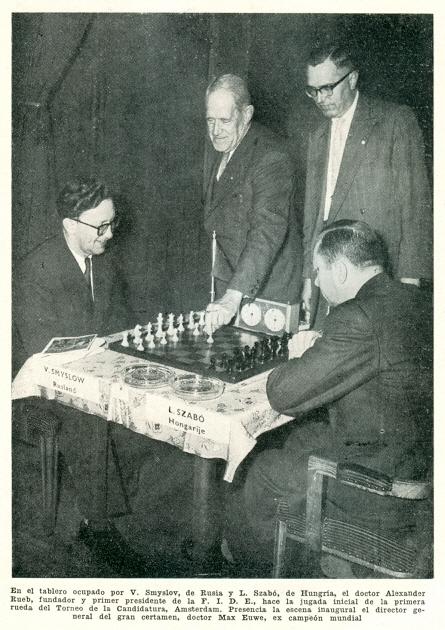

This photograph of V. Smyslov, A. Rueb, M. Euwe and L. Szabó at the 1956 Candidates’ tournament in the Netherlands is taken from page 161 of the May 1956 issue of Ajedrez (Buenos Aires):

(5377)

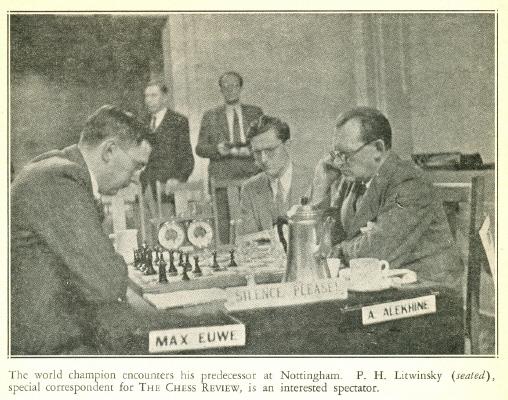

C.N. 593 quoted from page 80 of Lessons from My Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1958):

‘Both Alekhine and Capa were anxious to see Euwe do badly. I was rather amused when a most critical situation arose in my game with Euwe and both the ex-world champions whispered suggestions in my ear.’

Reuben Fine

Fine reiterated that claim about the game (a 19-move draw) on page 33 of his book Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship (New York, 1973):

‘... at the Nottingham tournament in 1936, when I was playing Euwe, then world champion after his defeat of Alekhine in 1935, both Alekhine and Capablanca spontaneously came up to me during the game to suggest moves, even though I had not asked them to do so.’

(5394)

This position (White to move) arose in the ninth match-game between Capablanca and Euwe in Amsterdam on 8 July 1931. The Cuban played 18 Rfb1 and the following year he discussed the game in a lecture in Havana which was reported on pages 242-243 of the August-September 1932 El Ajedrez Americano. He took issue with Znosko-Borovsky for the way he had criticized 18 Rfb1 ‘in his latest book on errors by grandmasters’. The Argentinian magazine, whose article was entitled ‘Capablanca refutes Znosko-Borovsky’, related (in our translation):

‘All the commentators – added Capablanca – had agreed on one assumption: that I should lose by means of the following continuation: 18...Nc4 (in the game Euwe played 18...O-O) 19 Qxb4 Rd1+ 20 Rxd1 (If 20 Bf1 Qxb4, followed by 21...Rxa1 and 22...Bh3.) 20...Qxb4 and Black would win.

This is clear and logical, but what the critics did not see, as our champion pointed out in his instructive and masterly lecture, is that White would have answered 18...Nc4 with 19 Nxf6+ ...

The main variation, according to Capablanca, would be 19...Kf7 (if 19...gxf6 then 20 Qxf6, attacking the bishop and the king’s rook and winning rather easily, and if instead 19...Ke7 then 20 Qxb4 with check) 20 Qxb4 Rd1+ 21 Rxd1 Qxb4 22 Ne4! and – still according to Capablanca – White should win despite the queen sacrifice. Black has many weak points, and the threats Rab1 and Ng5+ are difficult to neutralize. If, for instance, 22...h6, there would follow 23 Rab1 Qe7 (To protect the b-pawn.) 24 Bd6! Qd7 25 Nc5, followed by 26 Rxb7+, with gradual, decisive pressure.

Capablanca showed many variations to prove that after 22 Ne4!! it is only White who has winning chances.

Position (analysis) after 22 Ne4

Nonetheless, Capablanca declared that the critics were right to consider 18 Rfb1 inferior to 18 Rab1 (as El Ajedrez Americano mentioned in its annotations) but that although the move played by him was not the best it was far from leading to defeat.’

On page 279 of A Primer of Chess (London, 1935) Capablanca supplied the following assessment of 18 Rfb1:

Position after 25 Rd4 (analysis by Capablanca)

On page 213 of Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess (London, 1947) Harry Golombek gave the line ‘18...Nc4! and now if 19 Nxf6+ Kf7! 20 Qxb4 Rd1+ 21 Rxd1 Qxb4 22 Ne4 h6 23 Rab1 Qe7 24 Nd6+ Nxd6 25 Bxd6 Qd7 26 Be5 Qc8 and Black, having weathered the storm, should win easily enough’, without mentioning Capablanca or any other previous annotator. On page 237 of the algebraic edition (London, 1996) John Nunn added a footnote: ‘White can improve by 24 Bd6! winning the b7-pawn, after which White has a clear advantage. A more accurate 22nd move (possibly 22...Kg6) might give Black an edge, but he is certainly far from winning.’ It should be recalled that 24 Bd6! was given by Capablanca during his lecture.

Beyond the above analytical complexities – and see too page 37 of Schachmeister wie sie kämpfen und siegen by Alfred Brinckmann (Leipzig, 1932) – we should welcome clarification of Znosko-Borovsky’s involvement: where exactly did he criticize Capablanca’s play against Euwe at the time? We can find no book of his that would fit the bill, so was ‘book’ an error for ‘article’?

(5427)

A photograph of the boxing champion Manny Pacquiao playing chess is pointed out by Edward Zoerner (Redondo Beach, CA, USA).

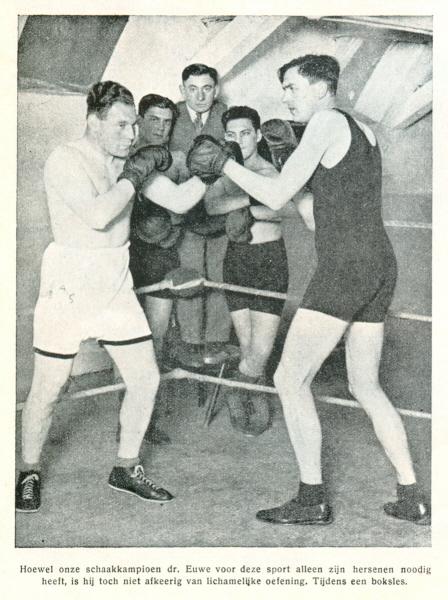

Lennox Lewis was mentioned in our Chess Awards article. There is a well-known picture (it accompanied the Time article discussed in C.N. 5559) of Fischer torse nu confronting a punchbag, and the photograph below of Euwe was published on page 10 of Zooals ik het zag (Amsterdam, 1935 and 1976):

Other chess masters’ names also come to mind, but here we conclude with a brief item, quoting E.B. Osborn, from page 267 of the August 1919 BCM:

(5570)

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) writes:

‘There is a line in the Winawer Variation of the French Defence which is often attributed to Euwe and in some sources is called the “Euwe-Gligorić line”. It occurs after 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 Ne7 7 Qg4 cxd4 8 Qxg7 Rg8 9 Qxh7 Qc7:

And now 10 Kd1, instead of 10 Ne2.

I have found two games with this line which were played in 1952 and 1953, and then three games played in 1960, after which the variation became more popular, but I have traced no games by either Euwe or Gligorić.

Moreover, already in 1960 Euwe wrote on page 79 of Part VIII of his Theorie der Schach-Eröffnungen (my translation):

“Another possibility in this kind of position is 10 Kd1, but the king move seems rather too sharp in this position.”

He then gave some analysis and presented moves from two games between E. Paoli and L. Schmid played in 1953 and 1960.

On what grounds has 10 Kd1 been named after Euwe (and Gligorić)?’

(5607)

The question asked in C.N. 5607 was why, after 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 Ne7 7 Qg4 cxd4 8 Qxg7 Rg8 9 Qxh7 Qc7, the move 10 Kd1 is credited to Euwe (and Gligorić).

Roland Kensdale (Aberdeen, Scotland) notes that a similar, though not identical, opening was seen in Gligorić v Petrosian, Candidates’ tournament, 1959 (1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 Qc7 7 Qg4 f5 8 Qg3 Ne7 9 Qxg7 Rg8 10 Qxh7 cxd4 11 Kd1) and that Gligorić discussed the line on pages 270-271 of his book I Play against Pieces (London, 2002). He gave the king move an exclamation mark and wrote:

‘The only way to meet the double threat on c3 and e5 and at the same time make possible a harmonious development of White’s pieces ...’

Moreover, Ola Winfridsson (Cambridge, England) quotes Mikhail Tal’s reference to that game on page 13 of Tal-Botvinnik 1960 (Milford, 2000), in a note after 11 Kd1 in the first game of that world title match:

‘... As far as I am concerned, the only game in which I came across the move 11 Kd1 (recommended, by the way, by Max Euwe) was in the above-mentioned Gligorić-Petrosian game.’

Our correspondent comments:

‘This is not the exact same variation (the moves 7...f5 8 Qg3 have been inserted), but the position is very similar (a pawn on f5 instead of f7). Perhaps some theoretician has confused the two variations and the moves 10 Kd1 and 11 Kd1.’

Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA) points out that the Tal v Botvinnik game was annotated in the second volume of Kasparov’s Predecessors series, with this comment about 11 Kd1 on page 417 of the English edition:

‘A fantastic move, recommended in 1948 by Euwe and first tried in the game Gligorić-Petrosian (Yugoslavia Candidates 1959).’

Mr Beck mentions too that page 32 of The French Defence by S. Gligorić and W. Uhlmann (New York, 1975) attributed 10 Kd1 to Euwe, and our correspondent adds:

‘Interestingly, the Tal v Botvinnik game is also annotated in the Gligorić/Uhlmann book, but it is merely stated that 11 Kd1 “offers the best prospects”, with no mention of Euwe or the Gligorić-Petrosian game (page 118).’

We conclude with an addition of our own, given that Gligorić’s book I Play against Pieces referred (on page 270) to a game between Reshevsky and Botvinnik in the 1948 world championship and that Kasparov’s book stated, correctly, that 11 Kd1 was ‘recommended in 1948 by Euwe’. In the Reshevsky v Botvinnik game this note appeared after 8 Qg3 cxd4 on pages 200-201 of Euwe’s book Wereld-Kampioenschap Schaken 1948 (Lochem, 1948):

‘Om met Pe7 te kunnen voortzetten, welke zet thans zou falen op 9 Dg7: Tg8 10 Dh7: cd4: 11 Kd1! en Wit heeft goede aanvalskansen (11...De5: faalt op 12 Pf3 benevens 13 cd4:). In aanmerking kwam echter ook 8...Pc6.’

Max Euwe and Mikhail Botvinnik (photograph published opposite page 161 of the above-mentioned book by Euwe)

(5613)

From Thomas Niessen:

‘I asked in C.N. 5607 why the line 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 Ne7 7 Qg4 cxd4 8 Qxg7 Rg8 9 Qxh7 Qc7 10 Kd1 is often attributed to Euwe (and Gligorić). C.N. 5613 contained some further information, from you and your readers, and the conclusion seems to be that the theoreticians confused two variations.

I have now found two remarks by Enrico Paoli, one dating from 1953 and the other from 1981, which point in another direction.

On pages 29-30 of his book on Venice, 1953 Paoli annotated his game against Lothar Schmid. No comment was appended to 10 Kd1, but Schmid’s reply 10...Nd7 received an exclamation mark and was described as an excellent novelty. Previously, Paoli added, 10...Nbc6 11 f4 Bd7 12 Nf3 had been played.

In fact, only two earlier games with 10 Kd1 seem to be known (Willborg v Nyman, Stockholm, 1952 and Karaklajić v Cala, Bled, 4 June 1953), and neither featured the line 10...Nbc6 11 f4 Bd7 12 Nf3.

In the tournament book Paoli also mentioned that Euwe had analysed the 8 Qxg7 line.

On pages 84-85 of the March 1981 Deutsche Schachzeitung Paoli annotated Taruffi v Renman, Reggio Emilia 1980-81, commenting after 10 Kd1 dxc3 (in my translation):

“I remember my game with Lothar Schmid at Venice, 1953 (won by Canal), where he continued 10...Nd7. This produced a new problem (I knew only Euwe’s 10...Nbc6, which he had analysed in Schach-Archiv) ...”

There is thus now another suggestion (in addition to the one in C.N. 5613) that Euwe published analysis of the line in or before 1953. Can it be traced?’

(6316)

Thomas Niessen writes:

‘In C.N. 5607 I asked why the line 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3+ 6 bxc3 Ne7 7 Qg4 cxd4 8 Qxg7 Rg8 9 Qxh7 Qc7 10 Kd1 is often attributed to Euwe (and Gligorić).

In C.N. 6316 a citation hints at the early issues of Euwe’s Schach-Archiv, and eventually I found that in the July 1952 number he suggested 10 Kd1, with an exclamation mark. He also gave some lines of play, from which Paoli took a number of moves, claiming that they had been played (see C.N. 6316).

However, I have now found that in the 7/8 1954 issue of Schach-Archiv Euwe withdrew his suggestion and noted that 10 Kd1 is “practically refuted” by the game Paoli v Schmid, Venice, 1953.

It can therefore be concluded that both the above line and the similar line discussed in C.N. 5613 were suggested by Euwe, and that only the latter has any connection with Gligorić.’

(6850)

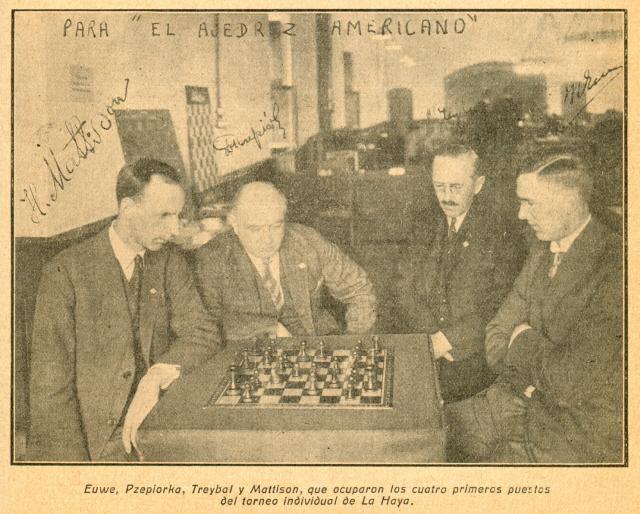

This photograph was published on page 403 of El Ajedrez Americano, October 1928:

(5637)

A detail has been provided by the Cleveland Public Library:

It is a Four Knights’ Game position arising after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Bb4 5 O-O O-O 6 d3 d6 7 Bg5 Ne7.

(12080)

See too A 1928 Chess Photograph.

From the archives of Frank Anderson comes this photograph (Amsterdam, 1954), forwarded to us by John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA):

The caption on the original states: ‘M. Euwe, Keres, Mrs Botvinnik, Postnikov/Botvinnik, Flohr’.

(5798)

From page 237 of Why You Lose at Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

‘I shall never forget the description of the final scene of the 1935 match for the world championship. Both Alekhine, the defeated champion, and Euwe, the new champion, were in tears. There was this difference: Alekhine, the defeated, wept tears of sorrow. Euwe, the victor, wept tears of joy.’

In which contemporary source did the ‘description’ in question appear?

(5907)

Prompted by the Reinfeld quote regarding Euwe and Alekhine, Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) has sent us from his collection a photograph taken at the end of the 1935 world championship match:

(5914)

Concerning the involvement of Eric Klein in the 1935 world title match, see our feature article on him.

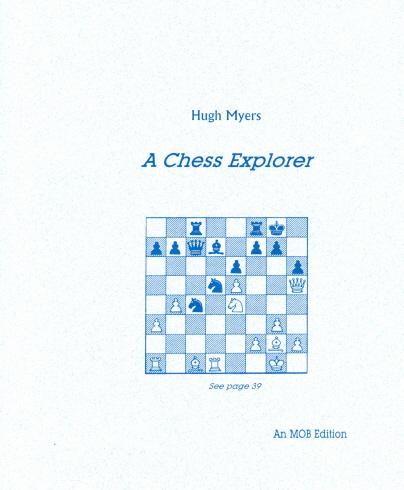

Hugh Myers’ book A Chess Explorer was published in 2002, and the following year he sent us a copy of a handwritten 12-page supplement which included a letter to him dated 4 March 1954 from Max Euwe. The former world champion commented, ‘your games are excellent and I hope to publish at least one of them in Ch. Arch.’ Myers wrote in 2003 that he was not sure which of his games he had submitted to Euwe. Did any of them appear in Chess Archives?

(6031)

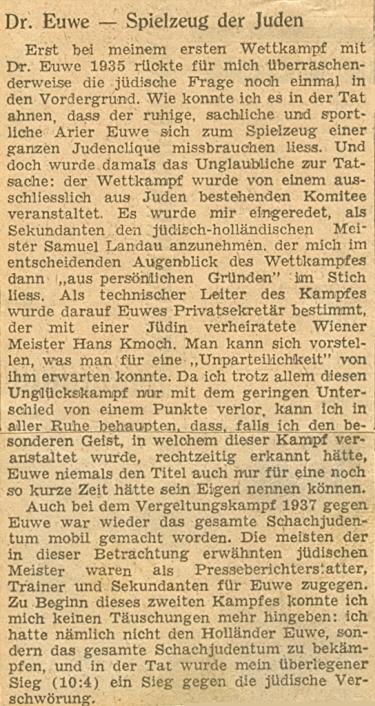

Regarding the anti-Semitic articles published in 1941 under Alekhine’s name, Henk Smout (Leiden, the Netherlands) writes:

‘The June-July 1942 issue of the Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond reported on a congress in Salzburg (held during a tournament won by Alekhine) concerning the foundation of an “Europaschachbund” (European Chess Federation). At the congress Alekhine was the French representative, and the magazine’s report (page 88) contained the following “rectification”:

“Gedurende dit congres heeft dr Aljechin tegenover den secretaris van den Ned. Schaakbond zijn leedwezen betuigd over het misverstand, dat zich in het afgeloopen jaar heeft voorgedaan als gevolg van een onjuiste publicatie betreffende het dr Euwe-comité, in het bijzonder ten opzichte van dr Euwe en de heeren Van Harten en Liket.”

[“During this congress Dr Alekhine expressed regret to the secretary of the Dutch Chess Organization about the misunderstanding which occurred last year in consequence of an incorrect publication concerning the Euwe committee, and in particular with respect to Dr Euwe and Messrs Van Harten and Liket.”]

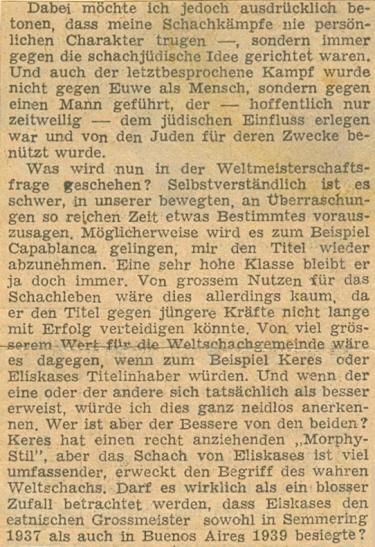

This was understandable only to those who knew the Pariser Zeitung of 23 March 1941 or the Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden of 2 April 1941. It related to the final anti-Semitic article, which stated that the organizing committee of the 1935 match with Euwe had consisted exclusively of Jews and that Euwe was a plaything of the Jews.

That article was not included in the Deutsche Schachzeitung’s serialization. The German magazine’s last instalment concluded on pages 82-84 of the June 1941 issue, and the promise “Fortsetzung folgt” was left unfulfilled, without explanation. It may, though, be relevant that Euwe had long been listed by the Deutsche Schachzeitung as a contributor. (He also became a “Mitarbeiter” of the Deutsche Schachblätter, the official organ of the Grossdeutscher Schachbund, as from the April 1941 issue.)

Approximately 40% of the text of the anti-Semitic articles was not republished in the Deutsche Schachzeitung and was therefore also absent from CHESS, which printed an English translation of what had appeared in the Deutsche Schachzeitung.’

Below we reproduce from our collection the relevant part of the article as it appeared in the Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden:

(6110)

Addition on 18 March 2022:

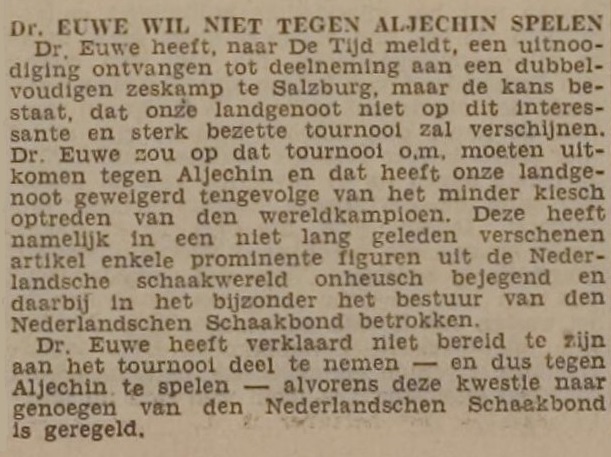

Mr Smout adds a report on page 2 of the Leidsch Dagblad, 14 November 1941 that Euwe was not prepared to play against Alekhine until the the issue of the latter’s quoted remarks about Dutch players and the Dutch Federation had been satisfactorily resolved:

From Google maps:

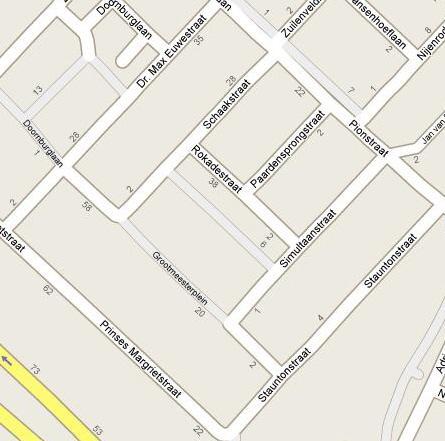

Henk Smout writes:

‘Max Euweplein in Amsterdam, Max Euwelaan in Rotterdam, Max Euweweg and Jan-Hein Donnerstraat in The Hague are all named after the masters.

Reestraat, Koningstraat, Koninginnestraat, Paardenstraat, Torenstraat, Kasteelstraat, Kastelenstraat, Loperstraat, Raadsherenstraat, Bisschopsplein in Zuilen and Bisschopsstraat in a number of Dutch and Belgian places have nothing to do with chess.’

(6211)

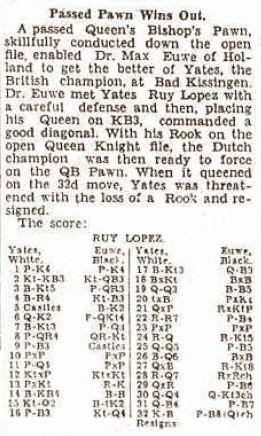

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) notes a report on page 6A of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 6 September 1928 that Euwe defeated Yates at that year’s Bad Kissingen tournament:

In reality, Euwe was White, and Yates’ victory was highly praised on pages 159-161 of the tournament book by Tartakower. Yates’ own notes appeared on pages 101-102 of his posthumous book One-Hundred-and-One of My Best Games of Chess (London, 1934).

(6682)

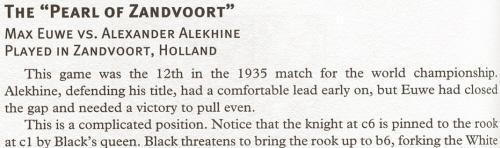

One of Euwe’s most famous wins is the ‘Pearl of Zandvoort’, the 26th game of his 1935 world title match against Alekhine. See, for instance, page 150 of Euwe’s From My Games 1920-1937 (London, 1938) and such well-known books as Wellmuth’s The Golden Treasury of Chess, Fine’s The World’s Great Chess Games and Schonberg’s Grandmasters of Chess. Various chess encyclopaedias (e.g. by Sunnucks, Golombek and Brace) have an entry for the ‘Pearl of Zandvoort’, and it is, in short, a matter on which no half-competent writer would go wrong.

From page 158 of The Big Book of Chess by Eric Schiller (New York, 2006):

The Euwe win given by Schiller as the ‘Pearl of Zandvoort’ was played in Amsterdam.

(6683)

From page 3 of The Groningen International Chess Tournament 1946 by M. Euwe and H. Kmoch, translated and edited by B.H. Wood (Sutton Coldfield, 1949):

‘Kotov and Smyslov received a medal from Euwe which is awarded to anybody who beats him; it was well meant and well taken.’

This implies that it was Euwe’s practice to make an award to players who defeated him. However, the original Dutch text, on page 20 of Groningen 1946 Het Staunton Wereldschaaktournooi (Groningen, 1947), was:

‘Kotof en Smislof kregen samen één plaquette van Euwe, gesticht door iemand die hem die van Euwe mocht winnen wilde beloonen. Het was goed bedoeld.’ [‘Kotov and Smyslov jointly received a plaque from Euwe, at the initiative of someone who wanted to reward the person beating Euwe. It was well intended.’]

(6845)

Our article Graves of Chess Masters has two photographs of the resting-place of Daniël Noteboom. We have now received from Jan Koppenaal (Noordwijk, the Netherlands), who was President of the Daniël Noteboom Chess Club from 1972 to 1997, a photograph of the funeral ceremony in 1932, with Max Euwe among the mourners.

(6846)

Mr Koppenaal has also sent us a photograph of Euwe with his pupils outside the Gemeentelijk Lyceum voor meisjes in Amsterdam (1930).

(6846)

White to move

This position arose at the end of Janowsky v Capablanca, New York, 1916. White played 46 Rxe6+, and on page 217 of The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played (New York, 1965) Irving Chernev wrote:

‘A spite check. Janowsky must realize there isn’t one chance in a million that Capablanca will move 46...K-R4, and allow himself to be mated.’

Chernev wrote similarly on page 96 of his book on Capablanca’s endings.

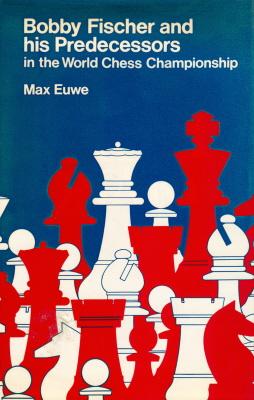

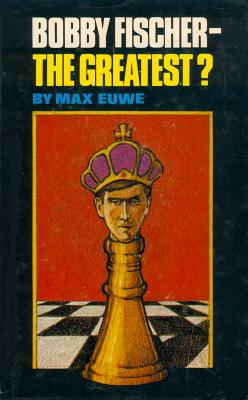

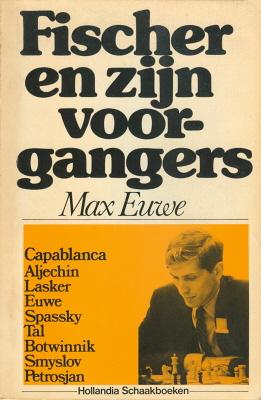

Naturally the Cuban played 46...Kh7, whereupon Janowsky resigned. Even so, the following appeared at the bottom of page 39 of Bobby Fischer and his Predecessors in the World Chess Championship by Max Euwe (London, 1976):

The mistake was left uncorrected in the US edition, Bobby Fischer – The Greatest? (New York, 1979). The Dutch version of the book, Fischer en zijn voorgangers (Baarn, 1975), was also wrong. From page 72:

Strangely, the imprint page indicates that the English edition came first and was translated into Dutch by Euwe:

In fact, Bobby Fischer and his Predecessors in the World Chess Championship was dated 1976, not 1975, and did not appear until summer 1977 (BCM, July 1977, page 314). On page vi of the book Euwe wrote:

‘I am very grateful to Mr Steve Wygle of Columbus, Ohio, for his careful reading of the entire manuscript, for his checking of the accuracy of the scores of the games, and for his valuable suggestions on the organization of the material. I wish to thank my friend and collaborator, Dr Walter Meiden, of the Ohio State University, for his suggestions on presentation and style.’

Are more details available about the exact genesis of Euwe’s ‘predecessors’ work?

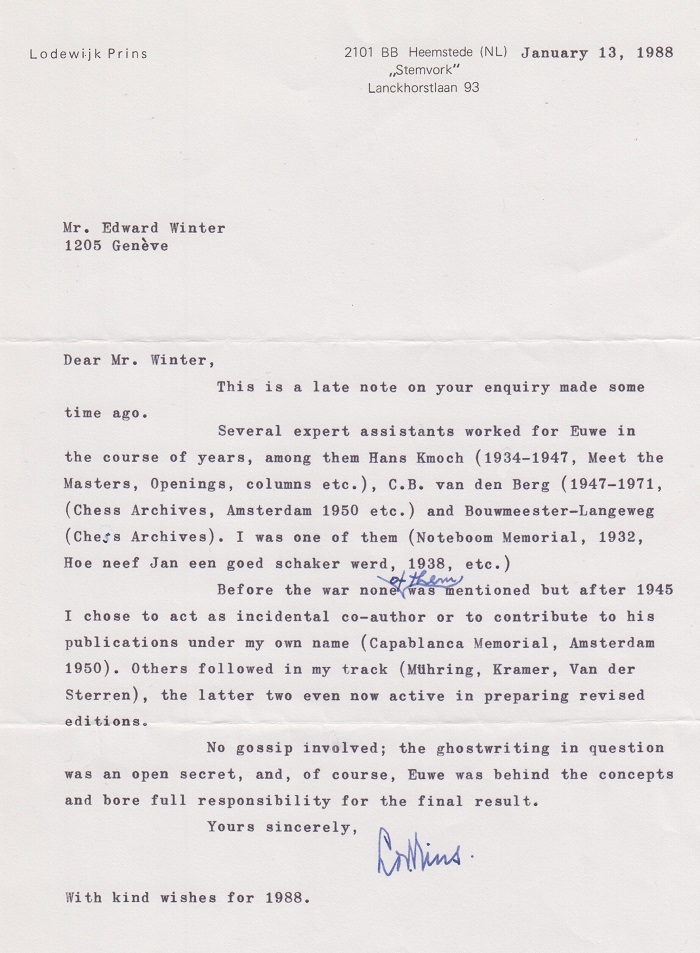

Concerning the more general issue of authorship of Euwe’s books, in C.N. 1529 Lodewijk Prins (Heemstede, the Netherlands) informed us:

‘Several expert assistants worked for Euwe over the years, among them Hans Kmoch (1934-1947, Meet the Masters, openings, columns, etc.), C.B. van den Berg (1947-1971, Chess Archives, Amsterdam, 1950, etc.) and Bouwmeester-Langeweg (Chess Archives). I was one of them (the Noteboom memorial book in 1932, Hoe neef Jan een goed schaker wordt in 1938 [sic], etc.)

Before the War, none of us was mentioned, but after 1945 I chose to act as incidental co-author or to contribute to his publications under my own name (the Capablanca memorial book and Amsterdam, 1950; for the Capablanca book I did most of the work, including literary and analytical research). Others followed in my track (Mühring, Kramer, van der Sterren), and the latter two are even now active in preparing revised editions.

The ghost-writing in question was an open secret and, of course, Euwe was behind the concepts and bore full responsibility for the final result.’

From our archives a photograph of Euwe and his wife, with, handwritten overleaf, ‘Gröbming, 1.6.1979’:

(6866)

Under the heading ‘Concentration of errors’, C.N. 93 stated:

On page 64 of Meet the Masters by M. Euwe the match Capablanca-Corzo is discussed:

‘In 1900, when only 12 years old, he beat J. Corzo by four games to nil, with six draws, in a match for the championship of Cuba.’

In fact, the match took place in 1901, not 1900. Capa was 13, not 12; he lost three games, not zero; the match was not for the championship of Cuba.

The year of the match seems to have caused widespread confusion on account of Capablanca’s statement in My Chess Career that he was 12, whereas he celebrated his 13th birthday just after the match had started. Nonetheless, the date 1900 appears only in the index; it is hardly fair to claim that Capablanca forgot the year of the match himself – the facts, correct in all particulars, are given in his book of the Havana, 1913 tournament.

A paragraph about Euwe by Walter Meiden on page 21 of the April 1982 Chess Life:

‘He was modest and unassuming; he tried to look at things from an unbiased point of view. He insisted on including in The Road to Chess Mastery, which had only master vs amateur games, one that he had lost to Capablanca – Game 7. “I played like an amateur in that game”, he said, and he showed in his marvelously clear way just how Capablanca won.’

The game was played at London, 1922.

(6867)

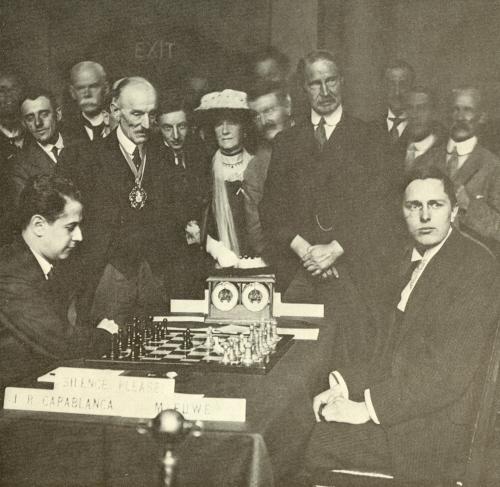

Our feature article on Andrew Bonar Law begins with these two photographs:

The above photograph, taken at the start of London, 1922 and with Bonar Law standing on the right, has been published quite extensively, e.g. on page 83 of A Book of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1973). A second shot from the same occasion appeared opposite page 216 of Glorias del Tablero “Capablanca” by José A. Gelabert (Havana, 1923):

Jan Koppenaal possesses a cloisonné tile (13cm x 13cm) manufactured by De Porceleyne Fles in Delft. It states ‘1935 – Dr Max Euwe – wereld kampioen – schaken’:

(6907)

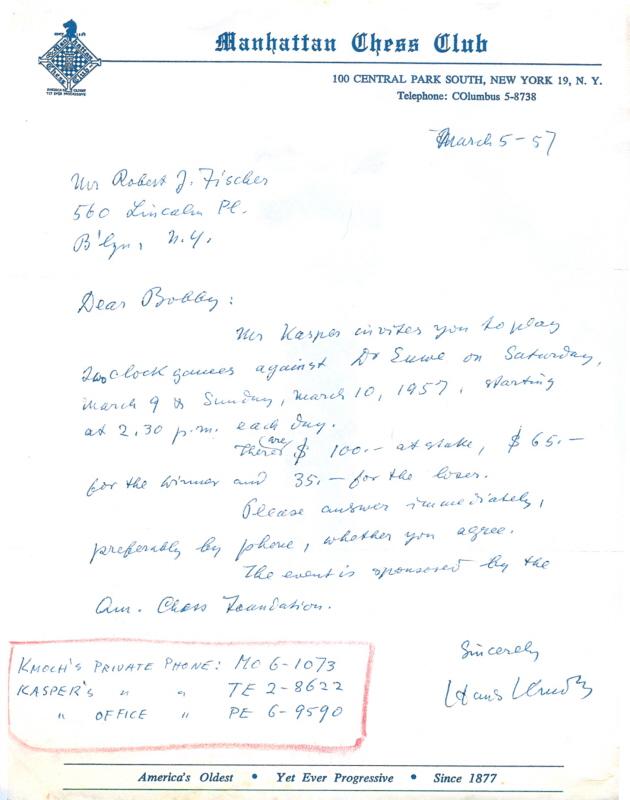

Courtesy of Frank Brady (New York, NY, USA) we reproduce a letter dated 5 March 1957 in which Hans Kmoch forwarded an invitation to Fischer to play two games against Euwe:

Fischer agreed, but it is only recently that the full score of the second game, a draw, has become known, thanks to Dr Brady’s researches.

A photograph showing play in the first game was on the front cover of the April 1957 issue of Chess Review:

(6995)

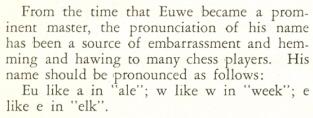

From page 3 of the 14 September 1935 CHESS:

‘For the benefit of those to whom Dutch pronunciation is a trouble, we might mention that “Euwe” is pronounced like “Minerva” without the “Min”.’

Some verse by H.D’O. Bernard was published on page 47 of the February 1941 BCM:

‘A Dutchman exclaimed with some fervour –

“When writing to our Doctor Euwe

Kindly say it’s untrue we

Pronounce it as Youwe

It is rather more Yerver than Erver.”’

C.J.S. Purdy discussed the matter on page 137 of Chess World, 1 June 1950:

‘Euwe. There is no way of anglicizing this famous name satisfactorily, so the best idea is to get reasonably close to the Dutch. The “eu” is not pronounced “oy” as in German, but is a seasick sound between “oy” and “ee”. The “w” is between “w” and “v” and nearer “w”, Dr Euwe has explained to us. If you listen to a Dutchman you’ll hear him glide over it so lightly that you can take your pick. The normal English “near enough” pronunciation is “Erva” as in “Minerva”.’

On page 357 of the December 1958 Chess Review J.S. Battell stated, ‘Euwe in Roman alphabet, pronounced Er-va’. The first edition of The Oxford Companion to Chess (page 105) had ‘ervour as in fervour’, whereas the second edition (page 126) gave ‘erwe as in Derwent’.

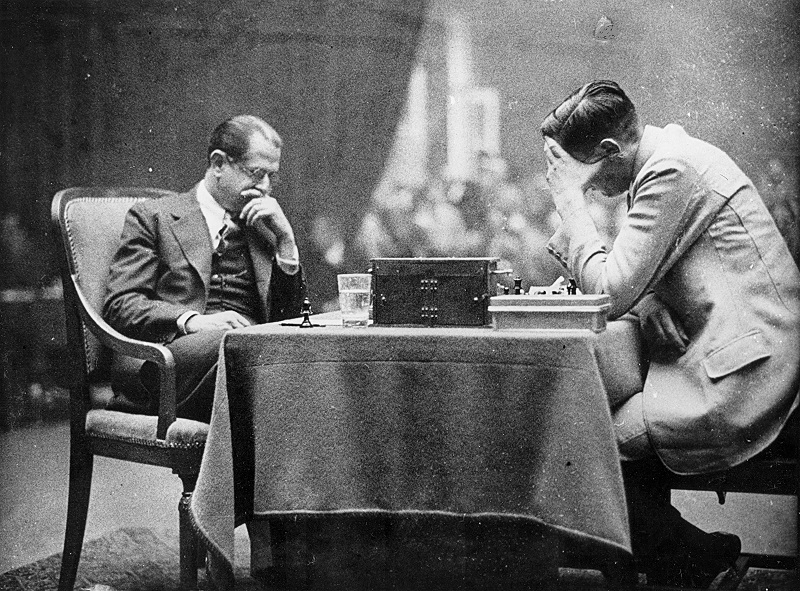

From our archives comes this photograph of Euwe during his match with Capablanca in 1931:

(7019)

Another photograph from the 1931 match, in our 1989 monograph on Capablanca:

A particularly dubious suggestion for pronouncing ‘Euwe’ was given on page 274 of the December 1935 Chess Review:

The proposal was repeated on page 262 of the magazine’s November 1937 issue.

(7048)

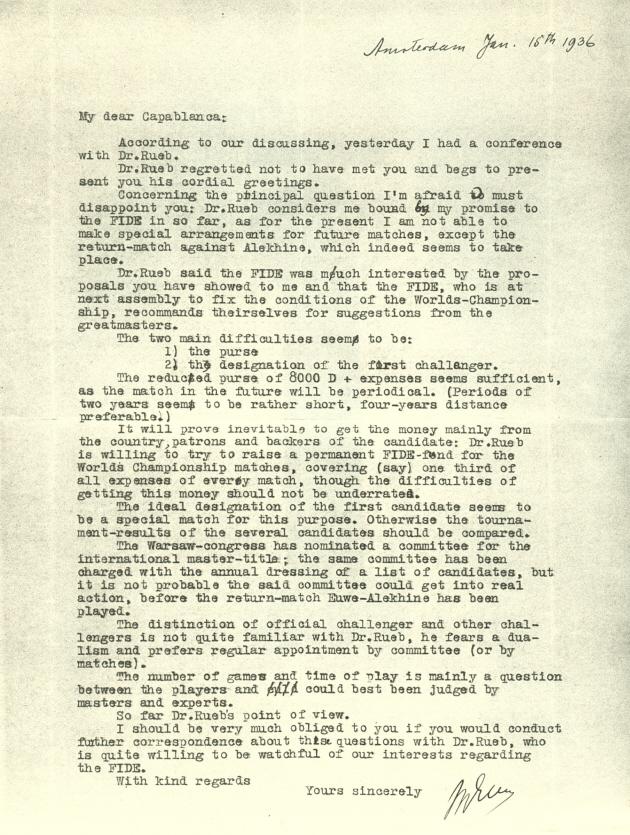

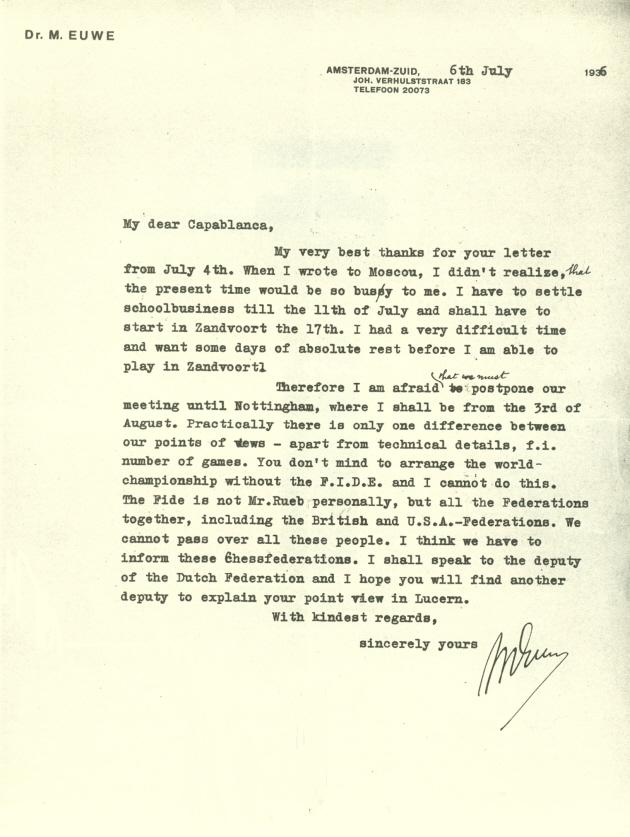

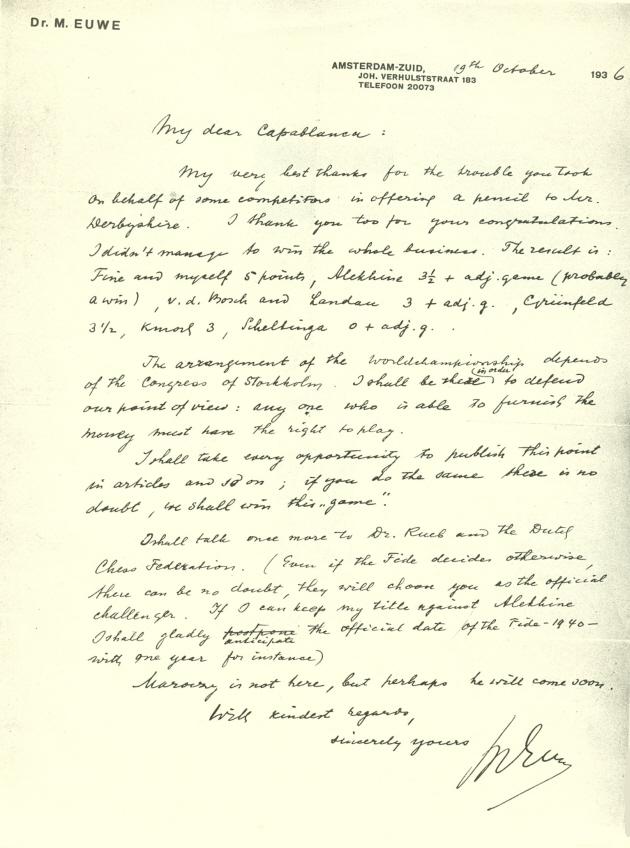

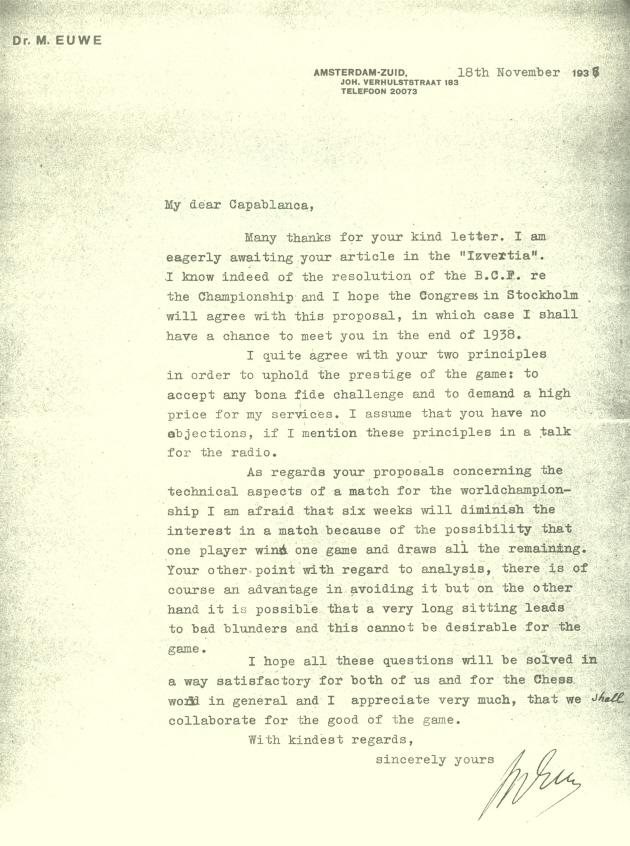

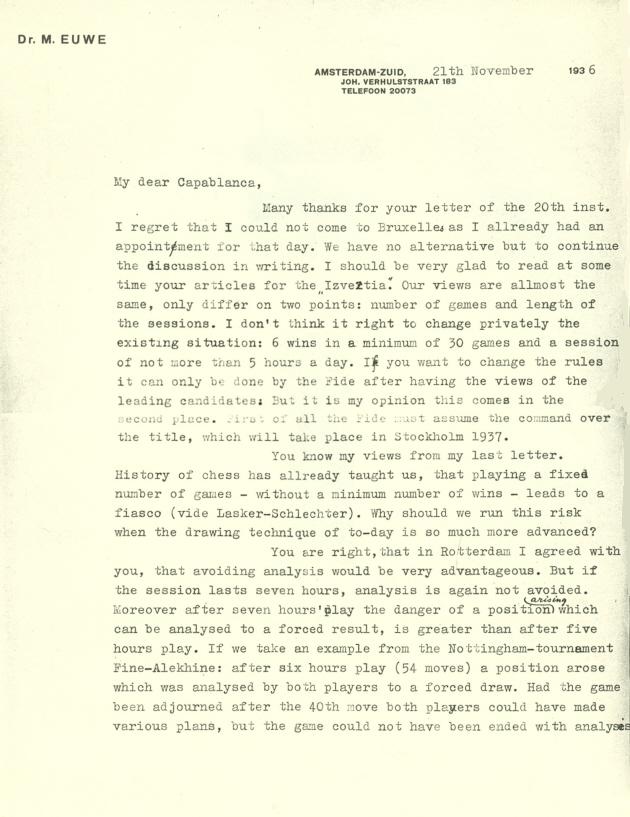

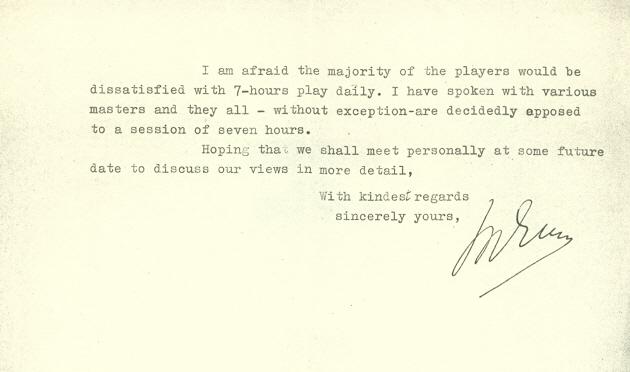

Our archives contain copies of five letters written by Euwe to Capablanca in 1936:

See too World Championship Disorder.

Robert Sherwood (E. Dummerston, VT, USA) draws attention to a snippet of film showing Alekhine and Euwe at the chessboard (the first part of the item).

(7153)

From Steve Wrinn:

‘C.N.s 6704 and 6720 discussed the claim by Chernev that Alekhine “once” stated, “There must be no reasoning from past moves, only from the present position”.

There is a good example of this view, expressed in Alekhine’s own words, in his comments on a note by Euwe in game 19 of their 1937 world championship match, on pages 134-135 of Alekhine’s book The World’s Chess Championship 1937 (London, 1938).

Euwe was White, and play went 13 Re1 Nb4 14 Bb5+ Kf8 15 Qe2 Bc5

16 Nd1. Having played 13 Rf1-e1, Euwe rejected 16 Re1-f1 and wrote:

“Of course not 16 R-B1, as this would admit something that was not true, namely, that 13 R-K1 was a mistake.”

Alekhine then added his own comment:

“An interesting remark, important for the comprehension of Dr Euwe’s chess personality; he simply does not want to admit that at the 16th move the best policy may be to return with the rook to KB1, and this solely because at the 13th move this rook went from KB1 to K1. For my part I confess that if I had White I would be satisfied with the fact that my 13th move had forced my opponent to lose the power to castle; and that I would have made my choice only on the basis of a close examination of the respective value of the moves possible – not taking into account which squares the corresponding pieces had occupied a few moves earlier. As a matter of fact it appears that 16 R-B1 would have been the simpler alternative; for in that case 16...B-B4 would have led to nothing after 17 P-QR3 Kt-B7 18 R-Kt1.”

So in this case a “once” quotation at least approaches the truth – for once.’

(7232)

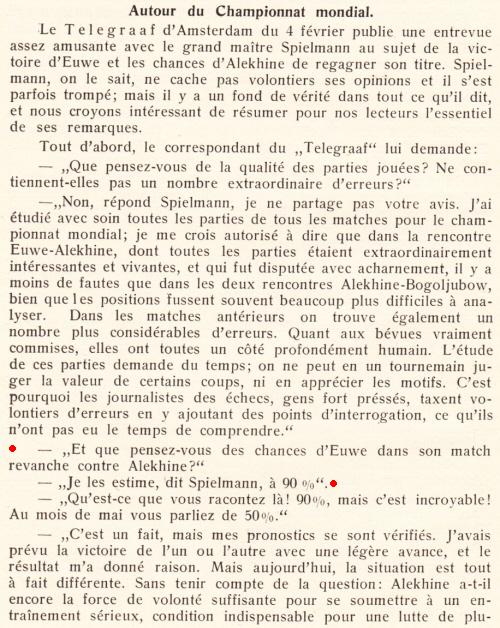

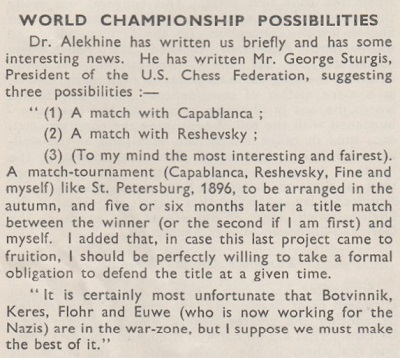

In 1936 which prominent master estimated at 90% Euwe’s chances of retaining the world championship in his return match against Alekhine?

(7929)

The answer is Rudolf Spielmann, as shown by an article on pages 68-69 of the May 1936 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

(7953)

Charles Sullivan (Davis, CA, USA) submits a game which he believes has not previously been published:

Max Euwe – Sargon 2.5

Detroit, 29 October 1979

King’s Fianchetto Defence

1 e4 g6 2 d4 Bg7 3 g3 Nf6 4 Bg2 d6 5 Ne2 O-O 6 O-O e5 7 c3 c5 8 d5 b6 9 f4 Bb7 10 fxe5 dxe5 11 Nd2 Nbd7 12 a4 Qc7 13 Nc4 Rae8 14 Qb3 Ng4 15 a5 bxa5 16 Rxa5 a6 17 h3 Ngf6 18 g4 Rb8 19 Qa2 Rfe8 20 Ng3 (Mr Sullivan points out the possibility 20 g5 Nh5 21 Rxf7.) 20...Bf8 21 g5 Nh5 22 Nxh5 gxh5 23 h4 Nb6 24 Nxb6 Qxb6 25 Be3 Rbd8 26 b4 Rc8

27 Qf2 Qg6 28 bxc5 Rcd8 29 c6 Bc8 30 Bb6 Rd6 31 Bc7 Re7 32 Bxd6 Qxd6 33 Qf6 Qxf6 34 Rxf6 Bg7 35 Rf1 Ra7 36 d6 Be6 37 d7 Ra8 38 Rxa6 Rb8 39 c7 Rf8 40 d8(Q) h6 41 Rxe6 fxe6 42 Rxf8+ Bxf8 43 Qxf8+ Kxf8 44 c8(Q)+ Kg7 45 Qxe6 hxg5 46 hxg5 Kf8 47 Qf6+ Ke8 48 g6 Kd7 49 Bh3+ Ke8 50 Qf7+ Kd8 51 Qd7 mate.

Our correspondent comments:

‘I recorded the game while standing next to Euwe. It was played between rounds two and three of the Tenth North American Computer Chess Championship in Detroit. Both sides played a move every five to 15 seconds or so, and Euwe stood for the entire game, which lasted approximately 20 minutes. Although he had no difficulty dispatching the computer, I was struck by how carefully he seemed to play, certainly not making his moves at blitz speed.’

(7949)

Thomas Höpfl (Schkopau, Germany) and Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) point out a video item featuring Euwe and Alekhine (1935) which is similar, but not identical, to one available in Chess Masters on Film.

From Thomas Höpfli there also comes a link to a video report on Arturo Pomar which includes Fischer speaking a few words of Spanish.

(8201)

The opening words of the chapter on Euwe on page 199 of The Great Chess Masters and Their Games by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1952):

‘“Dr Euwe is the most underrated player in the world.” Reuben Fine was absolutely correct when he made that flat statement in 1940.’

Fine’s observation, made slightly later than Reinfeld indicated, is given below, from page 200 of the November 1941 Chess Review:

‘To my mind Euwe is the most underrated player in the world. The common opinion (rarely heard in public but held by many people) is that he won the first championship match in 1935 because Alekhine drank too heavily, and that he lost the return match because Alekhine had restored his health.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Alekhine’s chess in the first match was no worse than the quality of chess he had been producing in the four or five years preceding the 1935 debacle, while Euwe’s play in the return encounter was considerably below his best form. For example, Alekhine’s games in his 1934 match against Bogoljubow were certainly no masterpieces, but Bogoljubow simply was not good enough to take advantage of it. And again in the second match Euwe made a number of incredible blunders.’

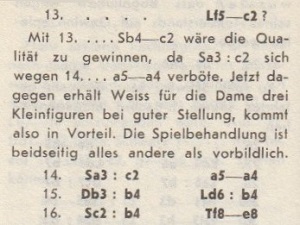

Source: Aljechin-Euwe by Guus Betlem Jr (Helmond, 1936)

‘He was described as “a man-eating tiger”’, commented page 34 of the February 1982 BCM at the start of ‘Dr Max Euwe (1901-1981) In Memoriam’, without any details being furnished. On page 73 of Max Euwe (Alkmaar, 2001) Alexander Münninghoff provided a ‘once’ version:

‘“An efficient man-eating tiger” was the epithet the American master Napier once coined for Euwe ...’

The phrase had been quoted by Lodewijk Prins on page 166 of Master Chess (London, 1950):

‘Euwe has been described by W.E. Napier as “an efficient, man-eating tiger”. The phrase sounds far-fetched, and many who regard the former world champion as primarily a positional player and theoretician will be surprised at this qualification. The following game from the Dutch championship, 1938 [a draw between van Scheltinga and Euwe] may make them change their minds.’

In item 147 in ‘unit two’ of Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (New York, 1934) W.E. Napier wrote:

‘Euwe v Alekhine

As contender for the proud title held by Alekhine, any game between them has special interest.

This one, played in Amsterdam, in 1926, exhibits a challenger of steady nerve, stout heart, and an efficiency like a man-eating tiger’s, – working at his trade.’

Napier then gave the eighth match-game between Euwe and Alekhine (The Hague, 1927, in fact), chopping off the last ten moves by putting ‘32 P-R6 Resigns’.

When the game, still shortened and still misdated, appeared on pages 251-252 of the single-volume edition of Napier’s book, Paul Morphy and The Golden Age of Chess (New York, 1957 and 1971), the introductory text was also curtailed, maladroitly:

‘This game, showing Euwe when he was a contender for Alekhine’s crown [sic – the match took place almost a year before Alekhine became world champion], exhibits a challenger of steady nerve, stout heart, and an efficiency like a man-eating tiger working at his trade.’

(8326)

‘The American grandmaster Reuben Fine called Euwe an efficient man-eating tiger.’

That comes from page 89 of My Chess (Milford, 2013), Hans Ree’s latest collection of superior nattering, but it is unclear why Fine’s name has been introduced. As regards the attribution to Napier (C.N. 8326), the following appeared on page 11 of Euwe’s Meet the Masters (London, 1940):

‘Napier once described Euwe as “an efficient man-eating tiger”.’

Page v of the Preface implies that this section was written by L. Prins and B.H. Wood.

Also from page 11 of Meet the Masters (immediately after the tiger quote):

‘Alekhine contributed a far more searching analysis of his [Euwe’s] style in an article in the Manchester Guardian soon after the conclusion of the last world’s championship match.’

That article (Manchester Guardian, 28 December 1937, pages 11-12) is given, together with others by Alekhine and Euwe in the same newspaper, in our latest feature article, Euwe and Alekhine on their 1937 Match.

(8335)

C.N. 7988 showed Max Blau astride a camel. Below is another example:

(8354)

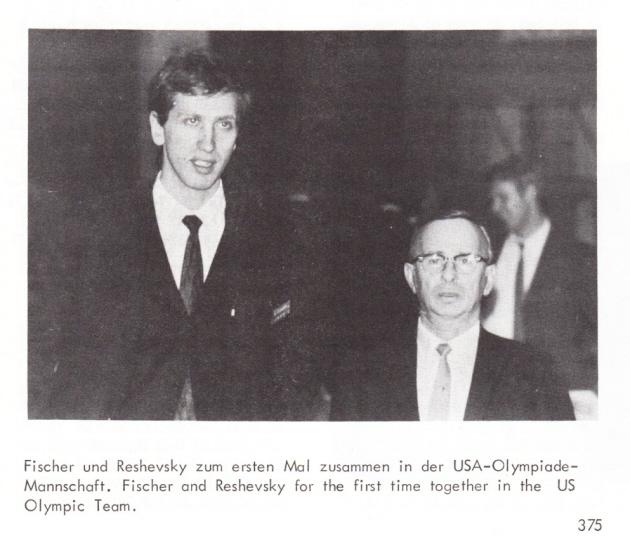

At the end of a brief review of Caïssas Weltreich by Max Euwe and Bob Spaak (Berlin-Frohnau, 1956) Harry Golombek wrote on page 63 of the March 1957 BCM that the book ...

‘is embellished by some excellent photographs, especially the one that gives such a humorous contrast between Reshevsky and Euwe’.

The picture was shown on page 94 of Chess Facts and Fables. On the same theme, the shot below comes from page 375 of Schach Express/Chess Express, October 1970, in a report on the Siegen Olympiad:

(8356)

‘He is a poet who creates a work of art out of something which would hardly inspire another man to send home a picture postcard.’

That well-known quote (Euwe on Alekhine) provides a small illustration of the current state of chess ‘scholarship’ on the Internet. It is commonly given sourcelessly, but what happens if, as is only reasonable, basic information is wanted about the occasion and context (e.g. whether Euwe was writing in general or was referring to a particular game or theme, and whether he expressed the sentiments before or after winning the world title from Alekhine)? We leave readers to try to find any websites which:

i) mention that the remark comes from Euwe’s book Meet the Masters (London, 1940). See pages 27-28.

ii) give the full paragraph with its context (Euwe’s introduction to Alekhine v Lasker, Zurich, 1934):

‘Curious is Alekhine’s knack of developing a seemingly harmless attack, within a few moves, into a hurricane which smashes down all resistance. His methods are simple; it is not so much any particular move which is important, as the whole series of moves – and the move after that! He is a poet who creates a work of art out of something which would hardly inspire another man to send home a picture postcard.’iii) provide, especially in the case of Dutch-language webpages, Euwe’s original text, from page 16 of Zóó schaken zij! (Amsterdam, 1938):

‘Eigenaardig is de kunst van Aljechin, een oogenschijnlijk onschuldigen aanval binnen enkele zetten te doen aangroeien tot een orkaan, welke alle tegenstand breekt. Hij gebruikt dan vaak heel eenvoudige middelen, waarbij niet elke zet afzonderlijk maar de heele reeks van zetten en vooral ook de volgende beslissende beteekenis heeft. Hij is dichter, die kunstwerken schept met dezelfde middelen, welke een ander nauwelijks voldoende zou vinden om een briefkaartje te schrijven.’

There have also been, of course, many printed versions of the Euwe quote without a source. Curiously, a few English-language publications continue, after the word ‘postcard’, with:

‘The wilder and more involved a position, the more beautiful the conceptions he can evolve.’

See, for instance, page 50 of The New Yorker, 28 October 1972 (an article by George Steiner on the 1972 world championship match), pages 15-16 of Steiner’s book The Sporting Scene (London, 1973) and Kasparov’s Foreword to Alexander Alekhine’s Best Games (London, 1996). All three publications had ‘conception’ in the singular.