Edward Winter

C.N. 5884 quoted from page 52 of Better Chess by William Hartston (London, 1997):

‘One of the best excuses I ever heard was from a man who had just lost to a female opponent. “She completely disrupted my thought processes”, he complained. “Every time I tried to calculate something, I’d begin: ‘I go here, he goes there’, and then I’d have to correct myself: ‘No, it’s I go here, she goes there’.”’

G.H. Diggle related another memorable explanation of defeat, concerning ‘the Lincoln bottom board of 1922, who complained that he had “lost his queen about the third move and couldn’t seem to get going after that”.’ The reminiscence appeared in an article by Diggle in the August 1979 issue of Newsflash, reprinted on page 50 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984). On page 66 of Chess Characters Diggle reported a comment which he had overheard in a league match: ‘Fancy losing to YOU!’

In the present article, though, we shall be looking at the heyday of self-exculpation: the nineteenth century. A familiar quote was mentioned in C.N. 2051 (see pages 322-323 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves). John Nunn asked which player originally commented that he had never beaten a healthy opponent, and some readers subsequently drew attention to the following assertion by B.H. Wood in the 1949 Illustrated London News which was anthologized on page 10 of The Treasury of Chess Lore by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1951):

‘It was old Burn, veteran British master of the ’90s, who was heard to remark plaintively towards the end of his long life that he had never had the satisfaction of beating a perfectly healthy opponent.’

The same passage (with a repetition of the word ‘never’) was reproduced by Wood on page 78 of CHESS, January 1952, but it has not been possible to find any link between the quote and Amos Burn. In C.N. 4189, though, we noted that page 2 of Chess Pie, 1936 had an article entitled ‘Humours of Chess’ by E.B. Osborn (‘Literary Editor of the Morning Post’). It concerned H.E. Bird (‘most lovable of all the old masters’), with whom he was personally acquainted. Osborn remarked:

‘Dear Old Bird would say that he had hardly ever beaten a healthy player.’

The question, therefore, is whether B.H. Wood, writing over a decade later, had the Osborn article in mind but mistakenly referred to Burn instead of Bird.

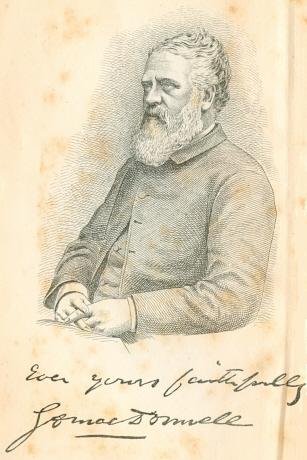

Henry Edward Bird (frontispiece to his book Chess History and Reminiscences)

C.N. 2118 quoted Charles Tomlinson from pages 54-55 of the February 1891 BCM:

‘Few men will admit the superiority of an opponent, and he who loses finds generally something in himself to account for defeat; or, as Löwenthal once remarked to me, “He always has a doctor’s certificate in his pocket!”’

A standard primer on the subject is the chapter ‘Excuses for Losing Games’ on pages 191-200 of Chess Life-Pictures by G.A. MacDonnell (London, 1883). The full text was cited in C.N. 4036, and some extracts are given here:

First let me notice the pre-prandial and post-prandial excuses. At one time it is, “I cannot play because I have not had my dinner”; and at another time, “I cannot play because I have had my dinner.” I have never yet had the good or the ill fortune to engage one of these gentlemen at the particular time when his chess powers were in real working order; and as all time must either precede or follow dinner, I am at a loss to conceive when such a player can conduct his game in a manner satisfactory to himself.’ (page 191)

George Alcock MacDonnell

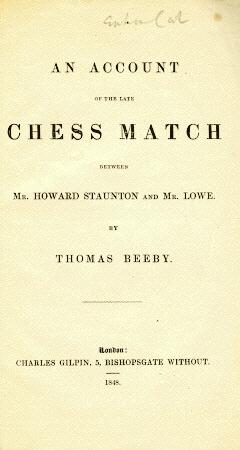

This brief selection of quotes concludes with a slice of magisterial sarcasm in a letter from Thomas Beeby to Hugh Alexander Kennedy dated 23 September 1848 and published in the Morning Post of 30 September 1848. The letter included an offer by Beeby to put up funds for a match of 25 games between Kennedy and Edward Lowe …

‘… such games to be published without note or comment, but upon the express understanding that, whatever may be the result, we hear nothing of indigestion, headache, indisposition, want of preparation, rust, or any other excuse, however ingenious, as palliative of defeat.’

Source: An Account of the Late Chess Match Between Mr Howard Staunton and Mr Lowe by T. Beeby (London, 1848), page 10.

The above article originally appeared at ChessBase.com.

Regarding pages 111-112 of Tarrasch’s book on his 1908 world championship match, Der Schachwettkampf Lasker-Tarrasch (Leipzig, 1908), Scott Thomson (New York) writes:

‘Tarrasch states that he planned to play a training match with a chess master, but that at the last moment the master failed to show up, thus depriving Tarrasch of needed practice and contributing to his very poor start to the match. Tarrasch is quite bitter about what he sees as a betrayal. Do you know the identity of this master?’

This matter was touched on by Emanuel Lasker in the New York Evening Post of 24 October 1908:

‘First, Tarrasch wrote that Düsseldorf has an ocean climate, that the sea winds upset him; then, that at the commencement of the match, he had not had his full force, because both Schlechter and Rubinstein failed, as they had promised, to practise with him; then, that I was lucky.’

See C.N. 1688 (on pages 188-189 of Chess Explorations), as well as page 325 of Siegbert Tarrasch Leben und Werk by Wolfgang Kamm (Unterhaching, 2004).

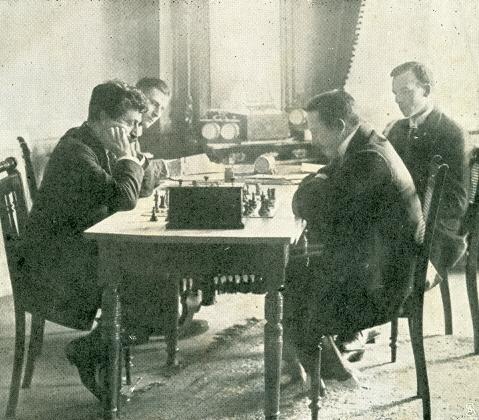

The photograph below is the frontispiece to The Championship Match: Lasker v Tarrasch by L. Hoffer (London, 1908):

Emanuel Lasker and Siegbert Tarrasch

See too our feature article Siegbert Tarrasch.

We add now, from page 16 of the Supplement to the Chess Player’s Chronicle, October 1873, a report on a speech by MacDonnell. The occasion was a meeting of the Counties’ Chess Association in Clifton on 8 August that year:

(6397)

From page 25 of A Popular Introduction to the Study and Practice of Chess (London, 1851), a book by S.S. Boden published anonymously when he was in his mid-twenties:

‘It is not every player that can lose a hard fought game with perfect equanimity. Few things are more annoying, indeed, than repeated loss, but we cannot but agree with all authorities on the subject, and strongly advise you, however trying the defeat, never to lose your temper, if you can help it. Endeavour to take a beating with good humour, and fight in quiet to the last. It is better never to make any excuse whatever after losing – apologizing for your bad play in such terms as “darkness”, “rust”, “single oversight”, “that one slip”, “headache”, “dizziness”, “thinking of other things”, “bad men and board”, etc., etc., etc. will only make your opponent laugh in his sleeve, or hypocritically condole with you. If you are, from any cause, “off your play”, say so before beginning, and not after losing.’

(10087)

From page 87 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 3 May 1899:

‘Another story of an excuse – same man. He had been cogitating some time and at length played. Notwithstanding his ruminations, however, he overlooked a slip mate on the board. “Ah!”, he exclaimed, “I was only looking for checks!”’

(10116)

From an article by Jeremy Gaige, ‘The Ethics of Chess’, on page 106 of Chess Review, April 1961:

The story is related on, for instance, pages 82-83 of The Chess Scene by David Levy and Stewart Reuben (London, 1974):

No source was given, naturally, but the ease with which anyone can fill space with such stuff is demonstrated by this extract from a ‘Round the Chess World’ article by G. Koltanowski on page 77 of CHESS, 14 October 1935:

The episode was also related on page 18 of Najdorf: Life and Games by T. Lissowski and A. Mikhalchishin (London, 2005). The conclusion:

On the strict basis of authoritative accounts, and ideally with the game-score, how can the incident best be summarized in a brief paragraph?

(11395)

‘I had a toothache during the first game. In the second game I had a headache. In the third game it was an attack of rheumatism. In the fourth game, I wasn’t feeling well. And in the fifth game? Well, must one have to win every game?’

Anyone using a search-engine for that remark, or a slightly different wording, will be presented with countless webpages. Most ascribe the comment to Tarrasch, some to Tartakower, and none to a precise source.

In print, it is no surprise to find A. Soltis writing the following sourcelessly on page 11 of Chess Life, June 1990:

‘And it was Tartakower who had perhaps the final word on excuses. Asked how he could lose so many games in a row at one tournament he replied: “I had a toothache during the first game, so I lost. In the second game I had a headache, so I lost. In the third game an attack of rheumatism in the left shoulder, so I lost. In the fourth game I wasn’t feeling at all well, so I lost. And in the fifth game – well, must I win every game in a tournament?”’

An earlier version was related by Harry Golombek on page 91 of the April 1953 BCM in a report on that year’s tournament in Bucharest, at which he ‘had a really dreadful phase’:

‘If asked to account for these six successive losses I think I cannot do better than to quote Dr Tartakower who on a similar occasion was explaining why he lost five games in a row in an international tournament. “The first”, he said, “I lost because of a very bad headache; during the second I didn’t feel at all well; I was afflicted by rheumatic twinges throughout the third; in the fourth I suffered acute toothache; and the fifth – well, must one win every game in a tournament?”’

Readers may care to imagine themselves entrusted with editing a chess quotations anthology. What to do with this ‘final word on excuses’? Omit it owing to the lack of a source? Give in detail the various versions and attributions? Plump and hope for the best (the process described in C.N. 9887)?

An attempt may first be made to establish when, if ever, Tartakower or Tarrasch lost five consecutive tournament games, and when the story was first attributed to, if not voiced by, either of them.

(11994)

Addition on 23 December 2024:

Emanuel Lasker, writing on page 9 of the New York Evening Post, 18 May 1907:

‘A man who can lose a game and yet acknowledge that he played his best is a rarity. Nowhere is vanity so rampant as in the ancient game of chess. In all other walks of life vanity is a stimulant for effort; in chess, it is an inventor of excuses, and its inventions are often ingenious. The loser was always “out of form” – what that signifies nobody knows. He was always “pressed for time” – of course, he began to take time when the situation became unfavorable. Then again, he “experimented in the opening” or he “did not know the gambit”, or he “has never studied the books”, implying that he is really a natural genius, etc., etc.’

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.