Edward Winter

Under the title ‘Sketches from the Chess World’, Ernst Falkbeer’s reminiscences on Staunton were published on page 5 of the May 1881 issue of Brentano’s Chess Monthly, translated from the Deutsche Illustrirte Zeitung (Leipzig) by Otto F. Jentz and originally published in the Neue Illustrirte Zeitung (Vienna):

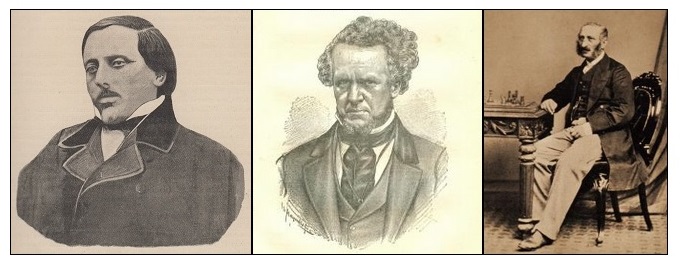

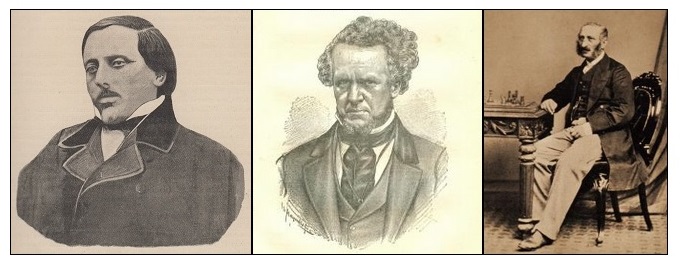

‘One of the most wonderful and original chess players that I had the good fortune to become acquainted with during my séjour in England was Howard Staunton. I might call him a typical figure of chess, at least as far as the manner of play of the Englishman is taken into consideration. Staunton, who died several years ago (1874), not very advanced in years, will remain in the memory of beginners who are not unacquainted with the literature of chess, on account of his theoretical and practical labors. He was the author of several highly celebrated works on chess; one of these (The Handbook) being even preferred by many to the Handbook of Bilguer’s, on account of its thoroughness.

His play was in the manner of the full-blooded Englishman, slow, thoughtful and far-seeing; but seldom surprising on account of an ingenious impromptu. Games of 10-12 hours’ duration came into vogue in England only through Staunton. He lived in the classic age of the game, when the world had time to busy itself with the peripatetics of the game; and the beautiful days of international combats had not yet passed. Staunton’s gigantic struggles with the Frenchman, St Amant, whom he at last overcame, with Cochrane, Buckle, Harrwitz, Löwenthal and many others, are engraved in the annals of chess. The man has a rich and varied past behind him. In his younger days he was a chess player. They say that he led a very adventurous life, that he made a wild, romantic marriage, which he afterwards dissolved. Tired of the artistic career which seemed to offer him no laurels, he threw himself into the arms of literature, and in this field he has certainly performed praiseworthy work. His critical, well-annotated edition of Shakespeare’s plays, which shows astonishing labor and learning, is esteemed by all acquainted with Shakespearean literature. He was also well known in literary circles as a regular collaborator on the Illustrated London News, in which he at the same time edited the chess department. But as chess player he was the lion of the day. Staunton was a man of winning, imposing appearance; an athletic form, with a truly lion-like countenance, and always most carefully dressed. He knew how, wherever and in whatever society he moved, to concentrate the attention of those present upon himself. It made a truly comic impression when, in the year 1855, the so-called “Midland Counties’ Chess Association” met for three days at Leamington, to which I was invited as a guest, to see the President of the Society, Lord Lyttelton, a man of small stature, but of measured and worthy behaviour, enter beside the mighty Staunton, who performed the honours of the day. In other respects Howard Staunton, smooth as his manners appeared, was liable to great and severe outbursts of passion. In his likings and dislikings he remained true to himself to his last day. Against Löwenthal, with whom he was previously on very good terms, he formed a great aversion, which he manifested in the most bitter manner on various occasions, no matter how bright the star of the German-Hungarian shone. Löwenthal survived Staunton but two years. The cause of this rupture between two once intimate friends is probably today still a mystery in English chess circles.’

On page 124 of the July 1881 issue of Brentano’s Chess Monthly it was pointed out, courtesy of Falkbeer himself, that ‘in his younger days he was a chess player’ should have read ‘in his younger days he was an actor’. Somewhere along the line there was a mix-up over Schachspieler and Schauspieler.

The July issue added that ‘concerning Herr Falkbeer’s reference to the quarrel between Staunton and Löwenthal, the well informed “Mars” says in Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News’ [21 May 1881, pages 226-227]:

‘Well, here is what I know on this subject: I never heard Staunton speak a word as to the cause of the quarrel, but I often heard him express in bitter language his dislike and contempt for the Hungarian. But Löwenthal a short time before his death gave me the following account of the matter: A correspondent wrote to the Era – wherein Löwenthal was at the time conducting a chess column – asking what was his score with Staunton. Löwenthal, in reply, did not, as well as I remember, specify the names of the players referred to, but he indicated them so very clearly to the initiated that there could be no mistake as to their identity, and claimed for himself a score exceeding his opponent’s in a certain ratio. Thereupon, another correspondent wrote to Staunton inquiring as to the score, and he claimed for himself a majority in a still greater ratio, and, at the same time, he sent for Löwenthal and requested of him a letter corroborative of his statement to be published in the Illustrated London News. Löwenthal was frightened, but refused his request on the ground that such a statement would be untrue; whereupon, Staunton told him he regarded him as an impostor, and should renounce his acquaintance. Who was right it is difficult, indeed, I may say impossible, to decide. In the case of matches the score is always made public. This is one of the few advantages pertaining to matches; but in off-hand games, played, as were the games referred to, without any stake, the players have to depend upon memory, a very treacherous calculator, that is but too apt to remember the games that have been won and to forget those that have been lost. [Passage omitted here by Brentano’s Chess Monthly: I, therefore, think that, as no actual score had been registered, it was scarcely fair for one player to claim publicly a victory, especially as his doing so was not likely to serve any desirable end, but, on the contrary, was only calculated to wound the susceptibilities of his opponent.] What particularly irritated Staunton in this matter was the seeming ingratitude of his protégé. He had been Löwenthal’s first and best friend from the time of his arrival in this country. He had treated him with unbounded hospitality, had recommended him to pupils, had used his influence successfully to get him appointed secretary to the St George’s Club at a salary of £100 a year, and therefore he considered, and rightly I think, that, even granting the score given by Löwenthal to be correct, he was not justified in making it public. On the other hand, I must add that Staunton’s persecution of the Hungarian from that time forward was wholly inexcusable.’

Translated into anecdotese, that becomes:

‘Staunton had a high reputation – and he was jealous of it. One time he confronted Löwenthal, a rival master, with, “I understand, Mr Löwenthal, that you have published a statement in your chess column to the effect that you have beaten me the majority of games”. “I did write that”, answered Löwenthal. “You will have to retract that assertion in your next issue”, said Staunton. “But I did beat you the majority of the games we played”, protested Löwenthal. “That does not matter”, Staunton replied, “you must retract the statement.”’

Source: The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev, pages 9-10.

(1624)

From page 149 of How to Play Chess Like a Champion by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

‘Staunton was pompous and bombastic, a self-appointed dictator of the chess world. On one occasion a rival published a statement that he had won the majority of his games with Staunton. The next time they met Staunton thundered, “You can’t print that!” His rival stammered feebly that the statement was true. “What’s that got to do with it? Of course it’s true!”, Staunton raged. “But you still can’t print it!”’

(4030)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.