Edward Winter

We present a compendium of reports on initiatives to create an international governing body for chess, prior to the founding of the Fédération Internationale des Echecs in 1924.

1900:

When, it may be wondered, was the need for an international body first voiced in the chess world? The following passage, concerning the Munich, 1900 tournament, is taken from page 562 of Amos Burn A Chess Biography by Richard Forster (Jefferson, 2004):

‘A side issue at the Munich congress, but one dear to Burn’s heart for quite some time, was the formation of an International Chess Masters’ Association on the day of the last round. On Burn’s initiative the masters present (including Lasker) discussed and sanctioned the provisional statutes which he had drawn up. The association’s goals were to promote the interests of chess in general and of the masters in particular, especially in connection with international tournaments and their conditions. A further important goal was to establish by way of election who did, and who did not, deserve to be called “master”, in order to prevent dilution of that title. The constitutive meeting of the Association was attended by Berger, Burn, W. Cohn, Janowsky, Lasker, Marco, Maróczy, Mieses, Pillsbury, Schlechter and Showalter. Berger was elected President and Marco honorary secretary for two and four years respectively. With Alapin, Blackburne, Chigorin, Gunsberg, Lipke, Marshall, Schiffers, Tarrasch, Teichmann, Weiss and Winawer invited to join, the novel undertaking seemed to be enjoying a promising start. Unfortunately, the Association – like so many of its successors – failed to achieve its goals. Despite having the Wiener Schachzeitung as its official medium from 1902 until publication was suspended in 1916, the organization remained dormant from an early stage onwards. Perhaps matters would have been different if Burn had been involved during the following period too, but with business again taking precedence over chess, that was not the case.’

(3387)

Concerning the ‘International Union of Chess Masters’, see, for instance, the letter from Georg Marco (‘Secrétaire de l’Union Internationale des Maîtres-ès-Echecs’) on pages 241-242 of La Stratégie, 20 August 1903.

1905:

The following appeared on page 121 of the January 1905 issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine:

‘The pending negotiations for the match between Mr Marshall and Mr Lasker for the title of chess champion of the world brings [sic] up for discussion a few questions which, it is believed, have never been fully considered by the chess public, and a study of them again forcibly demonstrates the necessity for some kind of organization by chess masters and the leading men of the chess world.’

(3387)

From the obituary of Arnous de Rivière in The Field, 16 September 1905:

‘Latterly his name came into prominence as the organizer of the Monte Carlo tournaments, and he was occupied with the drafting of a constitution for the establishment of an International Chess Association when death overtook him.’

What more is known about that initiative?

(5185)

1906:

From page 91 of the May 1906 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Proposed International Chess Association

The Committee of the International Chess Congress, at Ostend, beg to draw your attention to the proposed formation of an International Chess Association, the aims and objects of which are fully set out below. The Committee extend to you a most hearty invitation to be present at the inaugural meeting of the projected Association, which will take place at Ostend, on 4 July 1906.

The objects of the Association will be to foster and cultivate the highest class of chess, and to promote or give assistance in promoting International Chess Contests and Tournaments.

To issue a Charter for the Chess Championship, which will establish the holder of the title in his high place in a manner befitting the dignity of the noble game, and with proper pecuniary benefit to himself.

To afford aid or small pensions to famous players who, in their declining years, may find themselves in necessitous circumstances.

To form a Supreme Tribunal on all matters respecting the laws and practices of Chess and Chess contests.

It is not proposed to make this Association a federation of existing National Associations, though all Associations or Clubs will be very welcome as members on a minimum payment of a single member’s subscription. Such Associations as a rule have a sufficiently hard task set them to meet all the responsibilities incurred in their local work.

The International Chess Association will mainly appeal to private members drawn from the very large class of well-to-do lovers of the game distributed all over the world, who would like to avail themselves of an opportunity to contribute a little towards the organized support of the intellectual pastime which they admire, and which serves to fill so many pleasant hours of their lives; especially as they would do so with the conviction that their contributions would assist in stimulating the game towards its highest and noblest form of development, in the best manner possible for the benefit of Chess in general.

It is also proposed by gradual stages to raise a permanent endowment fund for the carrying out of the above objects, such fund to be established:

(1) By setting apart a portion of the annual income for this purpose;

(2) By donations from members; and

(3) By testamentary bequests.

To gain the confidence of the public it will be desirable that gentlemen of the highest standing in the Chess world should allow their names to be associated with the management, and to delegate to a capable Committee the framing of such rules and regulations for the financial control of the Association as will place its solidity and trustworthiness beyond the possibility of cavil or doubt.’

1912:

In a letter published on page 75 of the April 1912 American Chess Bulletin Albert E. Seibert of New York called for the creation of ‘a Supreme Court or Chess Council’. The context was the dispute between Lasker and Capablanca over terms and conditions for a world championship match:

‘No one man, whether title-holder or challenger, should have anything to say as to the conditions governing championship matches. Personal interests should be, not subordinated to the good of chess, but wholly disregarded, in determining the “how” and the “when” of a championship match.

... The proposed Supreme Court, which might be known as the Chess Council, must of course be, not only international, but also representative in order to command that ready acquiescence in its decrees which is to be desired. It should contain representatives of Austria, France, Germany, Great Britain, Russia and America, and, desirably, also representatives of other nations. Its members might be elected for a term of say three years, one-third of the membership being chosen annually.’

The initiative was discussed on page 609 of the May 1912 Chess Amateur, where the issue of funding was raised:

‘All this seems very right and proper, but there is no allusion to one important point, viz dollars. The proposed Supreme Chess Council would be powerless without the “sinews of war”. The British Chess Federation is not a wealthy corporation, the Associations and important chess clubs in the Empire and in foreign countries have little enough for their own requirements. The Supreme Council to secure the control of the world championship should have at its command a considerable revenue. Then it would be in a position to provide attractive stakes as well as a salary for the champion. Under these conditions it would have the right to enact special regulations and the power to enforce them. But who is to provide the funds? Can chessplayers without loss of self-respect appeal to the general public?’

Page 465 of the November 1912 BCM reported on the annual general meeting of the British Chess Federation in London on 19 October, during which the following resolution was adopted unanimously:

‘That this meeting of the Council of the British Chess Federation being of opinion that the present position whereby the champion of the world for the time being should be in a position to refuse any challenge except upon such terms as he himself may think fit to impose, is most unsatisfactory, and considers that in the interests of the game the conditions governing contests for the title “Champion of the World” should be definitely laid down, and urges the formation of an International Board to formulate such conditions.’

The BCM observed:

‘After passing this resolution the meeting instructed the executive committee of the Federation to draft tentative conditions to govern the contest, and then to submit same to the leading chess organizations.

We presume that one of the first steps taken will be to seek the co-operation of the German Chess Association, also of other chess societies of national status, and the views of leading master players.

We notice that there is no reference whatever in the resolution to the financial aspect of the case, but this is a point which will have to be provided for. In our opinion it will be futile to draft conditions for a contest which may require six to eight weeks to complete, unless the holder of the championship is compensated for the time, trouble and expense he is put to ...’

1913:

A report on page 435 of the November 1913 BCM regarding the British Chess Federation’s annual meeting in London on 18 October:

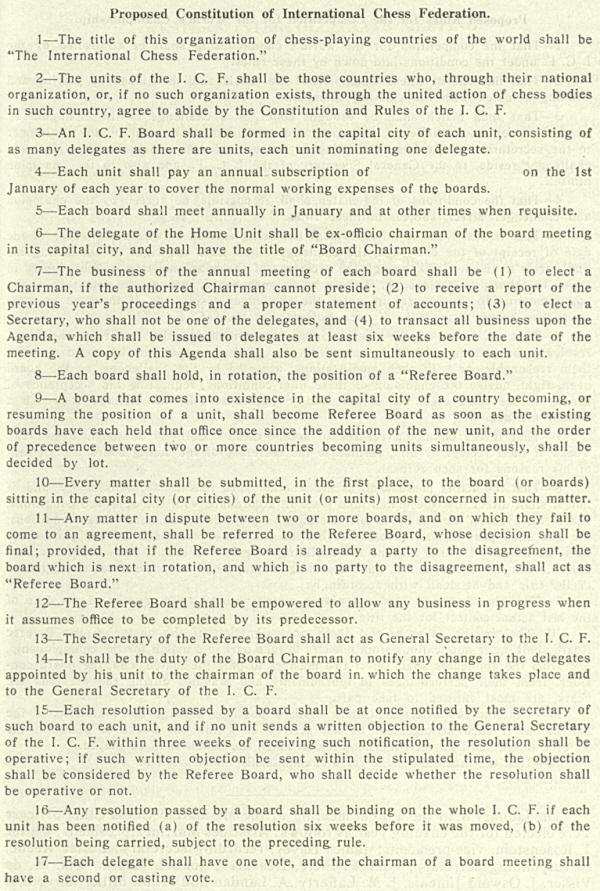

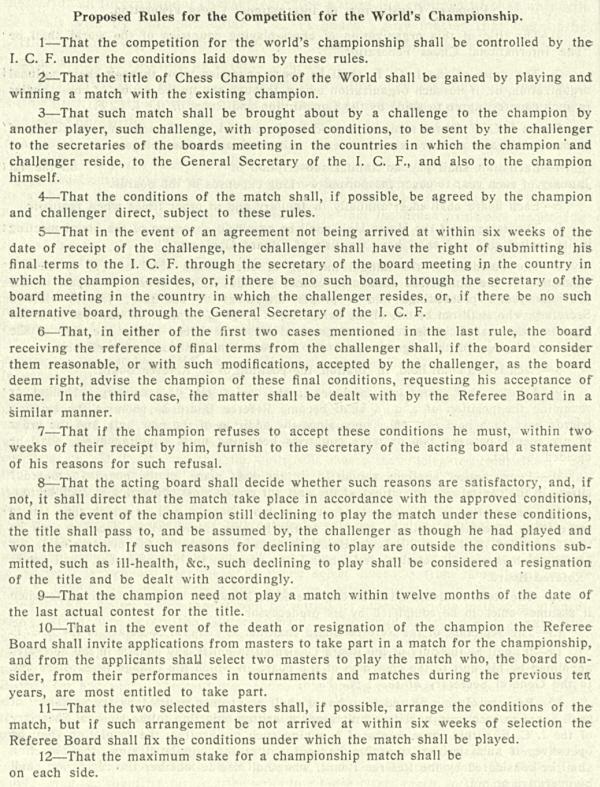

‘With regard to the proposed International Chess Federation, Articles of Association and also Rules for the World’s Championship Contest have been drafted, and will now be submitted to kindred chess authorities of other countries for consideration and approval or amendment. The general principle outlined in the proposed Constitution overcomes in great measure the difficulties of distance and cost.

The chief conditions of the suggested rules to govern the contest for the world’s championship provide that while the champion and the challenger have in the first place full liberty to make mutual arrangements, the challenger, failing an agreement being reached, has the right to submit the matter to the International Chess Federation, which may require the champion to play, or relinquish his title.’

From page 65 of the December 1913 Chess Amateur:

1914:

Below is the coverage on pages 25-28 of the February 1914 American Chess Bulletin:

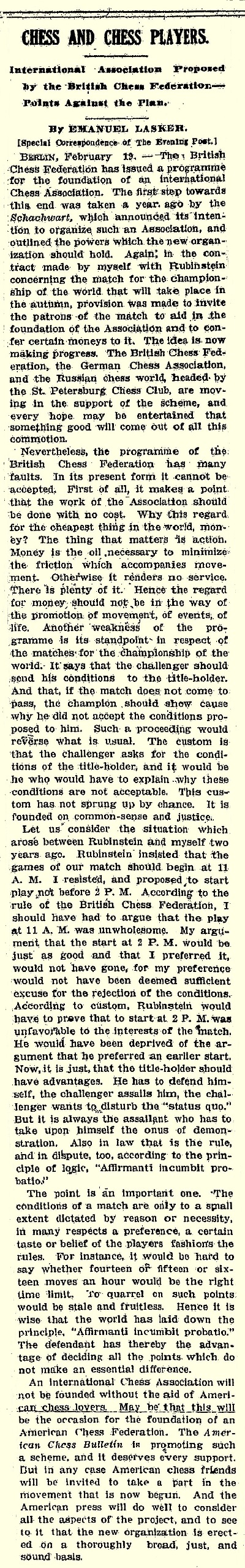

Emanuel Lasker commented on the document in his New York Evening Post column of 11 March 1914, page 10:

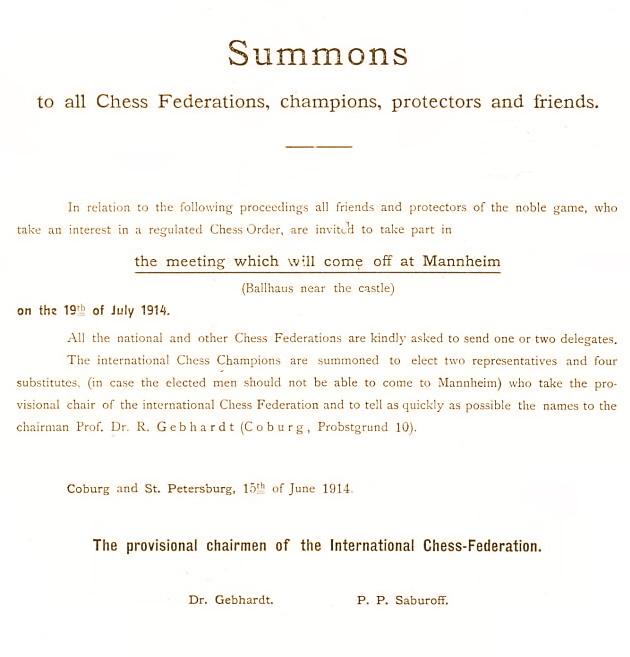

In C.N. 1476 Casto P. Abundo (Lucerne, Switerland) provided a document dated 15 June 1914 which serves as a reminder that steps to form an international federation were taken well before 1924. It is a ‘Summons to all Chess Federations, champions, protectors and friends’ and announces a meeting on 19 July 1914 at Mannheim. ‘The provisional chairmen of the International Chess Federation’ are named as Prof. Dr R. Gebhardt and P.P. Saburoff.

The scheme came about as a result of an initiative taken in St Petersburg on 23 April 1914, a conference attended by figures such as Bernstein, Gunsberg and Burn. ‘The purpose and tasks of the International Chess Federation’ would be:

‘A. Who shall be recognized as international Champion.’

‘B. Support for champions who are ill and invalided.’

‘C. The World Championship.’

‘D. Regulation on general questions (rules for the game notation and so on).’

‘Single members (as honourable members, protectors or real members) as well as confederations and associations may belong to the International Chess Federation.’

The full text of the above documents (of which a German edition is also on hand) was published on pages 32-34 of the January-February 1915 American Chess Bulletin under the title ‘The Russo-German Idea of Federation’.

There was some comment on the underlying issues in the August 1914 BCM (pages 290-291):

The outbreak of the Great War put an end to all such plans.

1920:

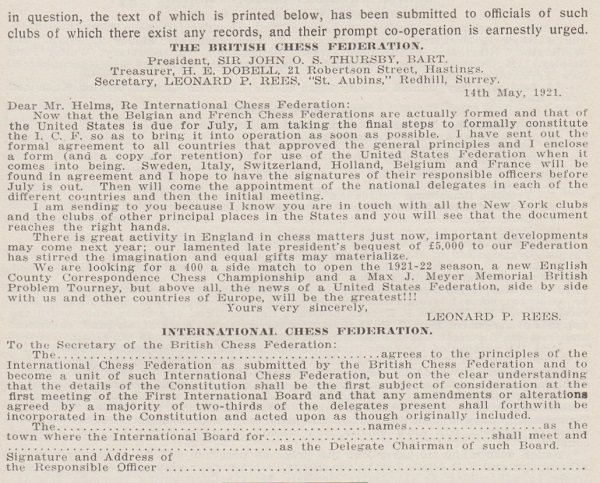

From pages 129-130 of the July-August 1920 American Chess Bulletin:

An additional item was published on page 143 of the September-October 1920 issue:

The following report appeared on page 12 of The Times (London) of Wednesday 4 August 1920:

‘A Reuter’s telegram of Monday’s date gives the news of the formal opening of the Gothenburg Tournament by the president, Mr Martin Anderson. The question of an international chess federation was discussed, and it was proposed that the Nordiska Shackforbundet [sic - Schackforbundet] should take the initiative in the constitution of such a federation. When one remembers that the professional players competing at Gothenburg are mostly the men who suggested the same movement at Mannheim in 1914, the meaning of the message becomes clear. It is an attempt by these same men to form an association that shall only regard the interests of the professional chess player, with the larger interests of chess entirely ignored. The British Chess Federation, on the other hand, is working in concert with the chess authorities of the world, to form a truly International Federation, in which the professional player will be welcome as a player, but will not be allowed to dominate the policy. Mr L.P. Rees, the BCF secretary, informs me that this recrudescence of the ill-advised Mannheim suggestions of 1914 will in no wise affect the policy of the British body.’

On pages 234-235 of its August 1920 issue the BCM commented with regard to the confusion over the anticipated Lasker v Capablanca world title match:

‘There is one distinct compensation in the otherwise unfortunate position which has now arisen with regard to the world’s championship title. This position would not have arisen if there had been in existence the International Chess Federation which was at least on the way to formation when the war broke out. We are, therefore, glad to hear that the subject of such a Federation is under serious discussion again. We hope that the discussion will be fruitful; and we believe that it has the chance of so being, if only the point be kept in mind that an International Constitution acceptable to the chessplayers of the world must be, not the product of a Chess Masters’ Union, but the work of international delegates selected for their impartiality and their tested organizing powers. The Masters must, of course, have their representatives; but, on the evidence of past history, they have always been notoriously incapable of managing chess affairs. Without paying the piper, they have claimed to call the tune – and often an extremely poor tune.

When the International Chess Federation becomes an accomplished fact, one of its most important duties will be to formulate the conditions under which the Championship shall be fought for in future – conditions not varying according to the caprice of the holder at any particular time, but carefully and fairly drawn up and universal in their application. Dr Lasker’s abdication and the consequent temporary lapsing of the title of the Chess Champion of the World will be advantageous rather than prejudicial to the cause of chess if they lead to the speedy setting up of a competent authority, which shall do away with the arbitrary proceedings of the past in connection with the Championship.’

The following comes from page 146 of the September-October 1920 Tidskrift för Schack:

And from pages 133-134 of the August 1921 issue of the Swedish magazine:

The latter report made it particularly clear that the Scandinavian federations were not in favour of such an international body until the political situation permitted it to be representative.

As quoted on page 107 of our 1989 monograph on Capablanca, the text below appeared in Brian Harley’s interview with him on page 16 of The Observer, 17 October 1920:

‘I sounded him gently on the burning question of an International Chess Federation.“Theoretically an excellent thing”, said the Cuban, “but you cannot exclude such important countries as Germany and Russia, which contain most of the great chess masters. The time will not be ripe for international control until the big European nations are again on friendly terms.”’

1921:

From pages 111-112 of the May-June 1921 American Chess Bulletin:

1922:

At the instigation of Capablanca, many of the world’s leading masters signed the London Rules.

1924:

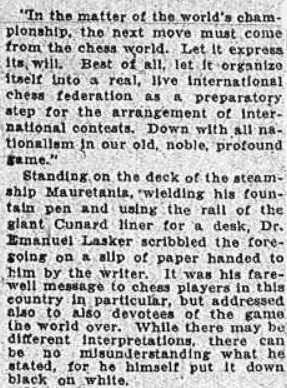

Emanuel Lasker was quoted in Hermann Helms’ chess column on page A3 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 12 June 1924:

(8918)

The Fédération Internationale des Echecs was founded in Paris. See Chess: The History of FIDE.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.