Edward Winter

Below is an article on Brad Darrach and Bobby Fischer which we contributed in November 2010 to ChessBase.com. It is followed by extensive complementary material posted in Chess Notes about Fischer’s dark side and, in particular, his virulent anti-Semitism. It is also demonstrated how Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam deceived New in Chess readers on the subject.

***

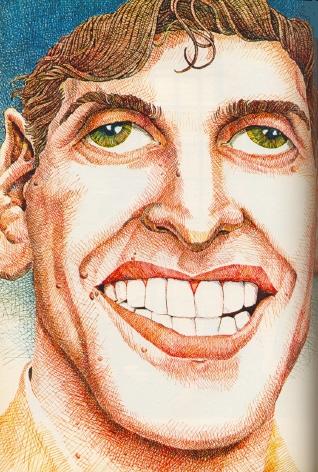

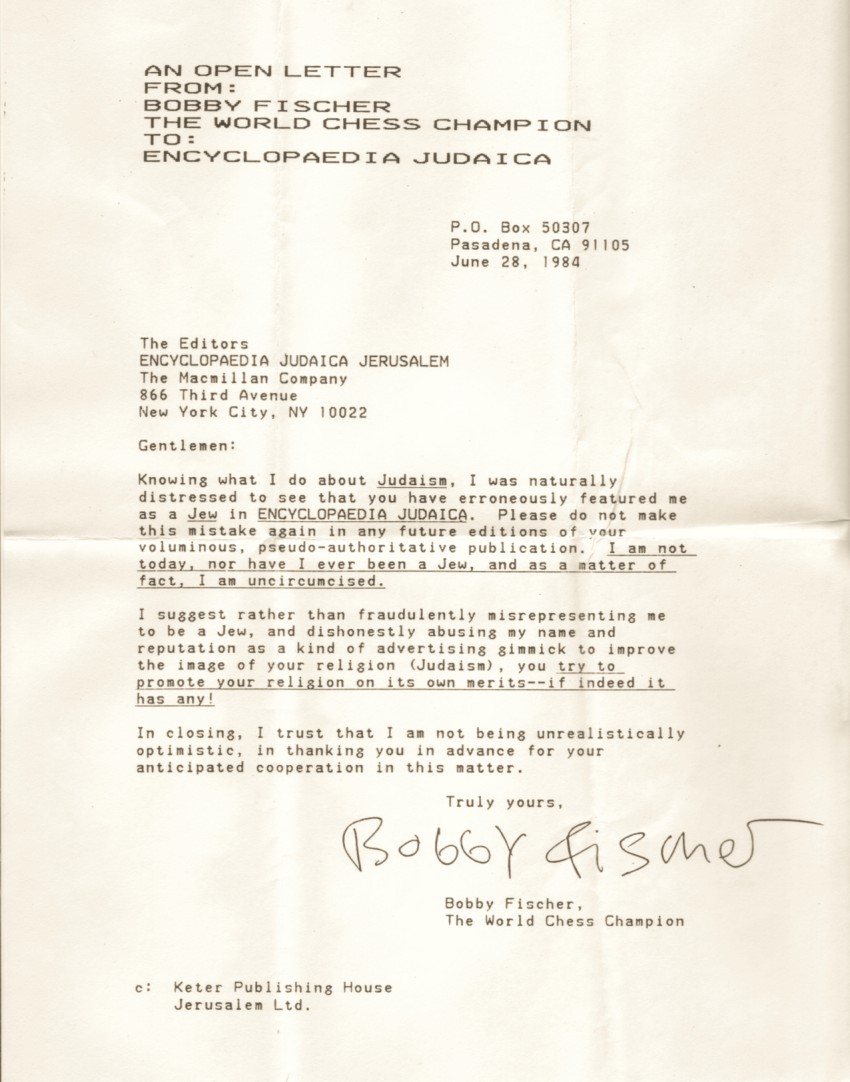

From page 678 of the October 1975 Chess Life & Review:

‘A UPI item in the New York Sunday News, datelined Los Angeles, 30 August, reports Bobby Fischer is suing Brad Darrach, Time-Life International and Stein and Day (publisher of Darrach’s Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World) for $20 million.’

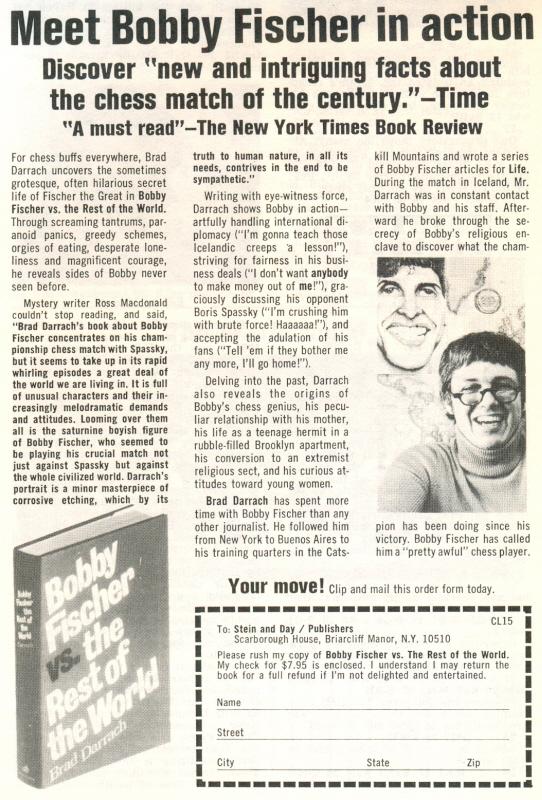

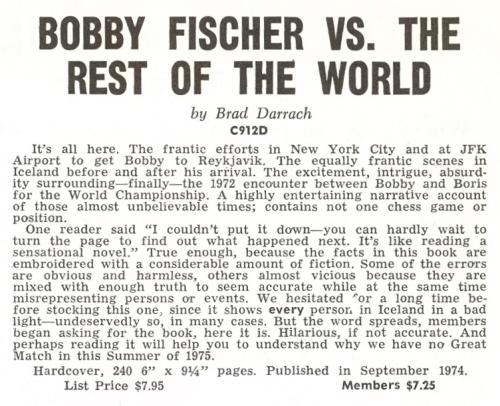

Earlier in the year, an advertisement had appeared in Chess Life & Review, on page 19 of the January 1975 issue:

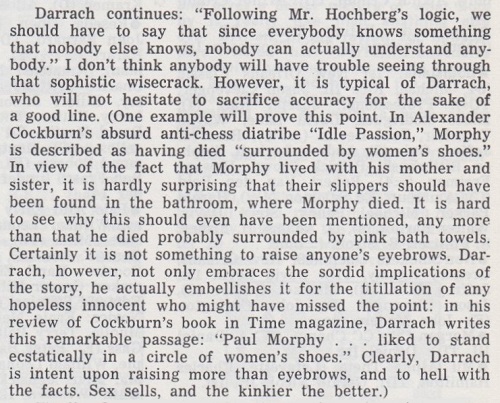

Chess Life & Review returned to the subject on pages 299-300 of the May 1975 edition, when its Editor, Burt Hochberg, discussed an article (‘by somebody named D. Keith Mano’) about Darrach’s book which had appeared in the New York Times Book Review, 13 October 1974. Mano had concluded that ‘men who play at the grandmaster level are, almost without exception, strange and unpleasant’, which prompted Hochberg to comment that Mano had been misled. Darrach’s book, Hochberg added, ‘is unbalanced and unfair; he has taken an extremely complicated and tortured genius and subjected him to an almost morbid scrutiny at the most critical and stressful period in his life’.

Hochberg (a fine writer and editor, unjustifiably disregarded nowadays) added:

‘Mr Mano has fallen into a trap; he sees Fischer the nut, Fischer the unreasonable child, Fischer the pathologically repulsive – all through Darrach’s eyes, for of course Mr Mano does not know Fischer. But Darrach does not really know Fischer either; no-one can really know him who does not understand chess. Strange Fischer may be, even to his friends in the chess world, and unpleasant he is at times – but who isn’t? In Fischer’s case, his unpleasantness is obvious to journalists because they know nothing about chess and are incapable of correctly interpreting anything Fischer says or does.’

The rebuttal by Hochberg concluded:

‘... Fischer is not perfect. He is not even close. But he deserves to be treated fairly and with some attempt at understanding. If he were not the man he is, he would not be the greatest chessplayer the world has ever known.’

Darrach’s reply in the newspaper (23 February 1975), which included the claim that ‘The book shows Fischer as superhuman, subhuman and normally human (whatever that is) in different proportions at different times’, was also discussed by Hochberg. He observed that Darrach ‘will not hesitate to sacrifice accuracy for the sake of a good line’ and concluded that the book mainly comprised ‘incidents chosen to show Fischer in the worst possible light’. It was ‘a hatchet job’.

On the next page of Chess Life & Review a reader requested Larry Evans’ view on whether the Darrach book was fair and accurate. The reply included the following opinions:

‘Darrach is not always fair and not always accurate, but his book is clever and gives a better picture of what Bobby is really like than anything else ever written. In my review for newspapers I noted that: “Darrach’s anecdotes are choice and indiscreet. Little escapes his keen eye, and he was the only reporter allowed to shadow Bobby after promising not to write a book about him.”’

Evans’ ‘review’ can be found on page 9 of his book The Chess Beat (Oxford, 1982). From the first paragraph:

‘This hilarious portrait of a genuine loner reads like a novel as it recreates the inglorious saga of the title match in Iceland. Bobby is revealed as an idiot-savant who can neither cope with nor fathom the forces driving him. A moody genius.’

(See also, in this connection, C.N. 323, reproduced on pages 208-209 of Chess Explorations.)

In contrast, Fischer’s biographer, Frank Brady, wrote on page 808 of the December 1975 Chess Life & Review:

‘... Fischer is no idiot savant, no Grandmaster Cro Magnon, as he is constantly portrayed in the popular press and in worthless hatchet jobs like Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World by Brad Darrach.’

The French term cropped up yet again in Yasser Seirawan’s discussion of Fischer on page 293 of the book he co-wrote with George Stefanovic on the 1992 Fischer v Spassky match, No Regrets (Seattle, 1992):

‘The media had a field day. They could write anything they wanted, both real and imagined.

The coup de grâce was Brad Darrach’s book, Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World, that forever nailed Bobby as the horrible combination of idiot savant and enfant terrible. This single work undoubtedly influenced multitudinous journalists to write about Bobby in exactly the same way. This book would prove to be a monkey on Bobby’s back. He would find himself forced to fight back against the media.’

The Darrach book has certainly been influential. For example, Bobby Fischer Goes to War by David Edmonds and John Eidinow (London, 2004) made liberal use of it and even had, on page 153, two sentences which started with the same demeaning phrase: ‘According to Darrach’.

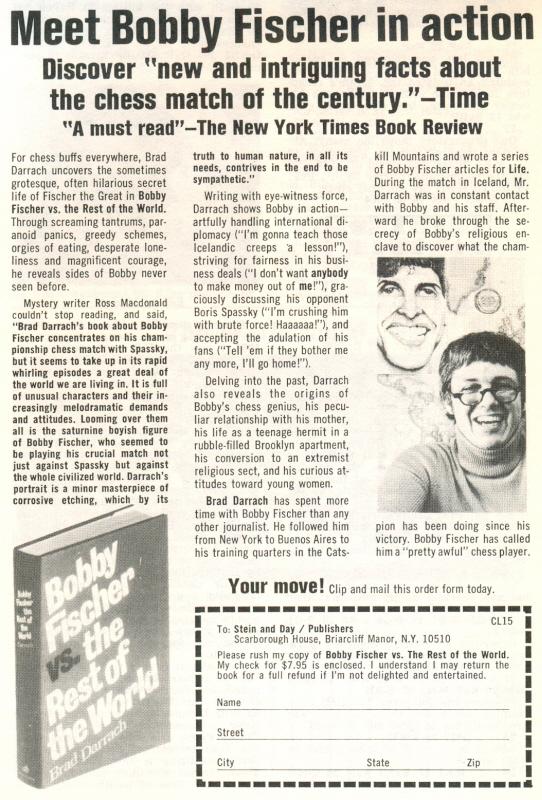

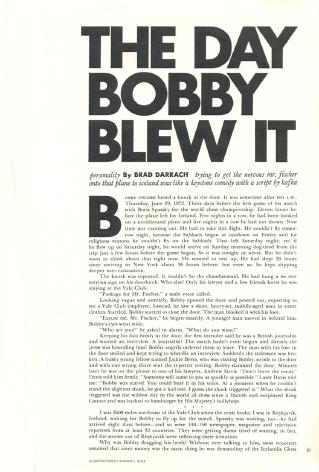

Fischer v Spassky in Reykjavik. Front-cover photograph of How Fischer Won by C.J.S. Purdy (Sydney, 1972)

This Crazy World of Chess by Larry Evans (New York, 2007) began with an item entitled ‘Fischer Letter to Marcos’ which Evans had originally presented in 2004. The letter was dated 27 January 1975 and began ‘Dear Mr President, How are you?’. It included this passage:

‘... I’ll be starting a suit of my own against someone who has written an incredibly boring book about me [Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World by Brad Darrach] that’s being pushed as “the most deliciously indiscreet biography ever written”. I think it should be called the most inaccurate biography ever written! But we can’t expect much accuracy from the press.’

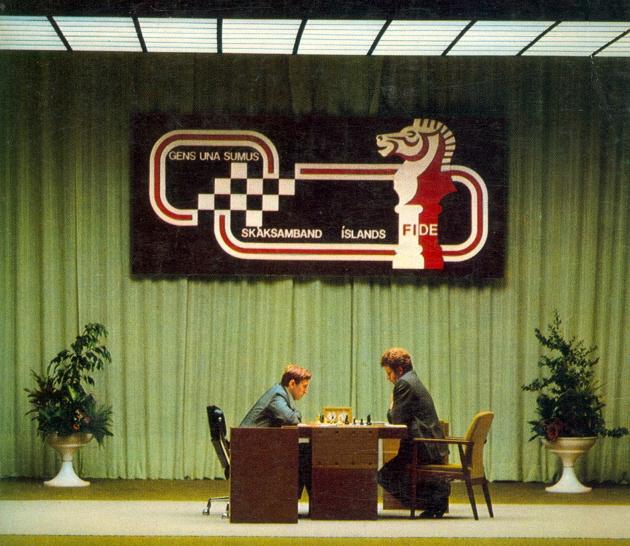

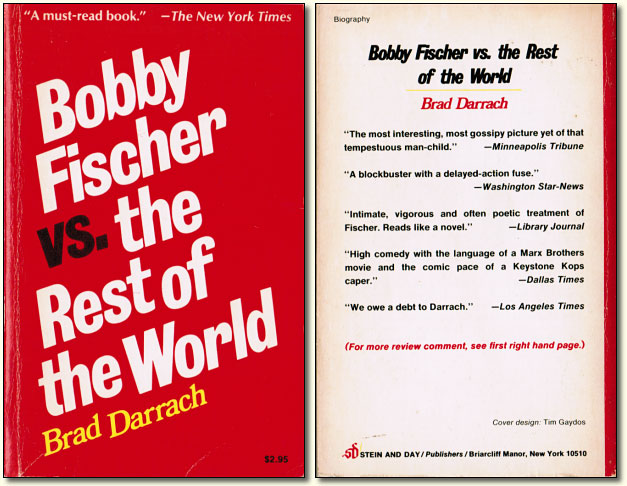

That last sentence, at least, is hardly open to dispute, and mainstream journalists have seldom paused to wonder how much of Darrach’s narrative and dialogue was true. The text is too colourful for any qualms about using it freely and with relish. In 1975 Stein and Day brought out a paperback edition, which quoted commendatory phrases such as the following from the Dallas Times:

‘High comedy with the language of a Marx Brothers movie and the comic pace of a Keystone Kops caper.’

But what about the issue of truth, the question of Fischer’s right to privacy and the wealth of direct speech? Discussing Chess Scandals: The 1978 World Chess Championship by E.B. Edmondson and M. Tal (Oxford, 1981) we commented in C.N. 509:

‘The late Colonel provides a mass of documentation tracing all the unbecoming disputes that marked the 1978 match as one of the most bitter in the game’s history. It seems strange that the 1972 Fischer-Spassky match did not give rise to such a book (we are discounting the scurrilous fiction of Brad Darrach).’

On 13 September 1983 Anthony Saidy (Santa Monica, CA, USA), who was frequently mentioned in Darrach’s book, wrote to us:

‘How accurate you were to describe Darrach’s “scurrilous fiction”! He writes superior pulp novel stuff.’

The views quoted so far have come from the compatriots of Fischer and Darrach, but the reception accorded to Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World across the Atlantic was also highly diverse. In fact, the BCM, edited by Brian Reilly, gave the book no reception of any kind, whereas the brasher CHESS (editor: B.H. Wood) had a field day. A cover page of the May/June 1975 issue mentioned that the book was in limited supply and gave readers every encouragement to place an early order:

‘Racy dialogue and a breathless hard-hitting style ... gripping stuff.

To what extent spontaneous conversation can be accurately reproduced years later is, of course, debatable.

The book is full of it, revealing R.J. Fischer as an obnoxious person indeed. As Brad Darrach has contributed to Life, Esquire, Harper’s and other magazines and (on the lines of this book) to the English Daily Telegraph supplement and attended the 1972 match at Reykjavik in person, we might assume that he has tackled his reportage responsibly. In the eyes of an ordinary man not blinded by hero-worship, Fischer emerges as a pretty noxious individual.’

Thus Fischer was described within a single paragraph as both obnoxious and noxious. Concerning Darrach, the grounds on which ‘we might assume that he has tackled his reportage responsibly’ scarcely appear rock-solid, but B.H. Wood was never an enemy of gossip.

The paperback edition of Darrach’s book received a mention among the cover pages of the February 1978 issue of CHESS, which showed that the magazine’s enthusiasm for such reportage had not diminished:

‘Deliciously sordid, and controversial, account of the clash of ’72. Racy, amusing prose and vivid portraits of even the minor characters give the book the air of a “non-fiction novel”.’

By that time, the lawsuit had come and gone. On page 238 of the May-June 1975 CHESS Frank Brady wrote:

‘... Fischer had other business matters to be discussed, including the possibilities of instigating a legal suit against author Brad Darrach for his book, Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World, most of which, Fischer claims, is libellous and untrue (as do many others in the chess world, including myself; Saidy calls it a “great work of fiction”) and also violates an agreement that Fischer had with Darrach that the latter would not write a book while covering the Fischer-Spassky match for Life magazine.’

Pages 80-81 of Playboy, July 1973

As mentioned earlier, Fischer sued Darrach for $20,000,000 in August 1975. The outcome of the case, two years later, was related by Frank Brady in a detailed article (‘Bobby Fischer Pilloried – His lawsuit collapses because he disdained legal aid’) on pages 364-365 of the September 1977 CHESS. Brady’s main points are quoted below:

‘... to solidify his reputation as a loner, Fischer prepared the legal brief himself, without the aid of an attorney.’

‘After two years of postponements on the part of the defendants, the case recently came before US District Court in the state of California and was dismissed by Judge Matt Byrne on the grounds that Fischer’s brief was not properly prepared.’

‘As Fischer’s biographer, I must admit that he is difficult, intense, and often detached but he is certainly not the uneducated and hysterical pet-baboon that Darrach so vividly but so inaccurately develops.’

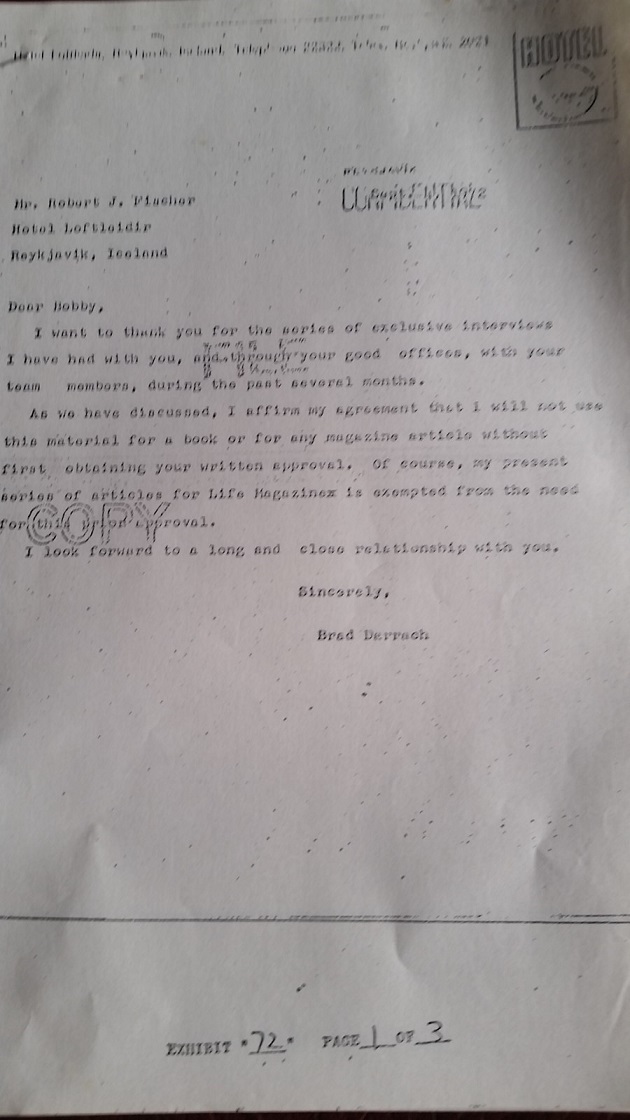

‘Darrach signed two documents, now in Fischer’s possession, stating that he would not write a book about Fischer. He also made numerous oral promises to that effect. I have before me copies of Darrach’s letters to Fischer.’

‘Using the ploy of postponements, hoping that Fischer would relent from lack of money to continue the case, was Darrach’s and his attorney’s only hope. As it developed, a technicality has temporarily saved them but Fischer will undoubtedly win the appeal ... if he allows himself to secure proper legal aid.’

‘Actually, without Bobby’s or anyone else’s knowledge Darrach had made the rounds of New York publishers prior to going to Iceland, attempting to secure a contract for a book. In Iceland, he snooped and wormed his way around attempting to find out as many intimate details in Bobby’s skeleton closet as he could. This was material that Life had no interest in publishing. Even Stein and Day, the publisher, deleted much gossip about Fischer’s private life before the book went to press.’

‘A large part of the book covers Fischer’s peregrinations before deciding to go to Iceland. Darrach weaves a colourful account of those moments and quotes long sections of dialogue, as though he were on the scene and heard the specific conversation. In fact, Darrach was already in Iceland, Fischer was in New York and most of the material that Darrach relates as history is just an exercise of his imagination.’

‘Other persons mentioned in the book are having trouble with Darrach. Two other chessplayers – one an international grandmaster – seriously considered libel suits against him. One of Fischer’s oldest and closest friends, hardly a public figure, is described in a particularly vicious and harmful way. He is currently preparing a lawsuit. Dr Max Euwe and Lothar Schmid are furious over Darrach’s unfair treatment of them.’

‘Certainly, these legal difficulties are a crucial factor in keeping Fischer from the board.’

We have yet to find details regarding an appeal by Fischer or any other lawsuits against Darrach.

In CHESS B.H. Wood conspicuously distanced himself from Brady’s analysis and gave the article this heading:

‘Frank Brady, official biographer of Fischer, whose opinions as an unreserved supporter of the ex-world champion are very definitely all his own.’

At the end of the Brady article CHESS opined:

‘Darrach is sometimes grudgingly fair to Fischer but obviously loathes him. He stresses the mad genius’s merciless eccentricities. He has researched assiduously though nobody could have attended every personal encounter written up in such vivid dialogue. The facts are all basically authentic, as to prompt the question again and again “Could anyone behave like this?”

A gripping book, almost a work of genius whose bad faith, which Frank Brady documents so fiercely, is another matter.’

It is unclear how CHESS felt competent to affirm that ‘the facts are all basically authentic’.

Bobby Fischer (Chess Life & Review, February 1973, page 71)

Independently of who was closest to the truth about Fischer in the 1970s, the subsequent revelations as to his character naturally cannot be ignored. In a 2005 Afterword to a feature article we observed:

‘From the late 1990s onwards he gave a series of radio interviews in which, egged on by standardless “broadcasters”, he came out with the most abject set of utterances ever made by a chess master.’

Yet there was even worse to come. The extent of Fischer’s depravity, anti-Semitism and, it must be said, apparent insanity was shown when a selection of his personal notes and other memorabilia was reproduced in Bobby Fischer Uncensored by David and Alessandra DeLucia (Darien, 2009).

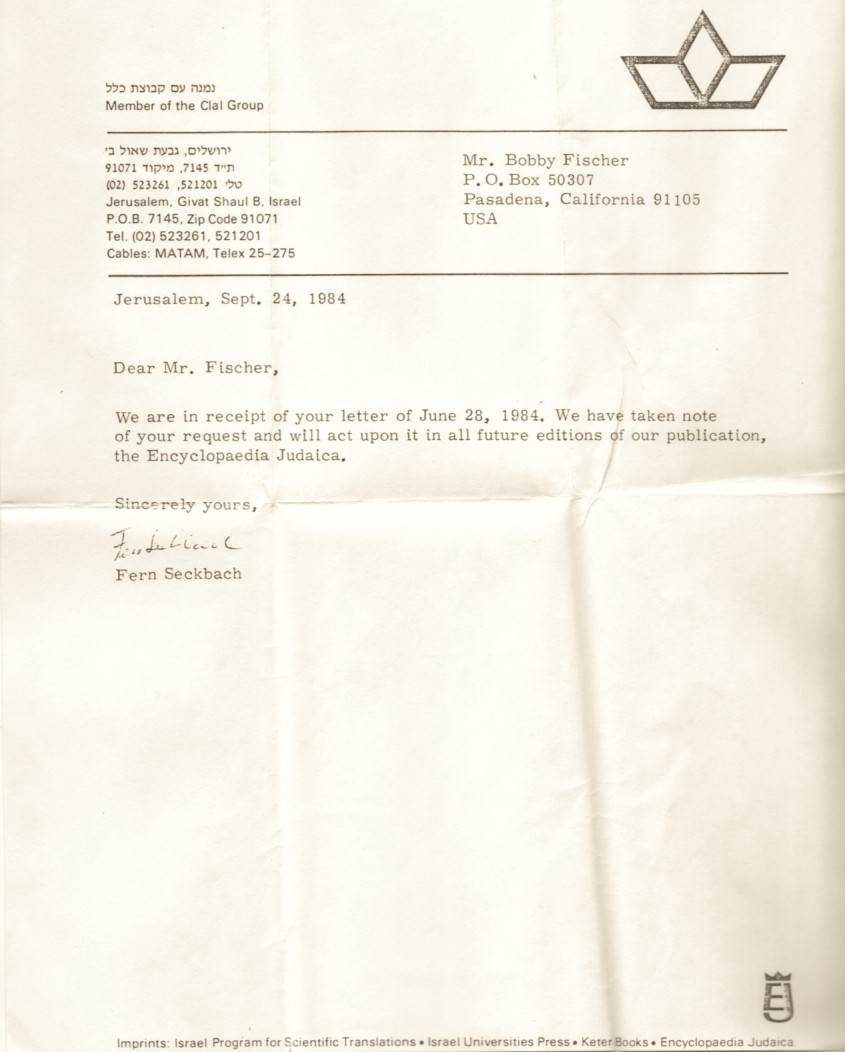

The following exchange of correspondence between Bobby Fischer and the Encyclopaedia Judaica was received by us in 1988 from Fischer’s address in Pasadena:

(1671)

Whereas Fischer, even during his periods of relative mental steadiness, viewed attempts to befriend or assist him with narrow-eyed paranoia, Kasparov’s failure has been at the opposite extreme and has, down the years, enabled some spectacularly unsuitable individuals to work their way in as neo-associates and pseudo-friends.

(3648)

There may never have been a chess book, even by Dimitrije Bjelica, with more direct speech than Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World by Brad Darrach (New York, 1974). The matter was touched on in a recent ChessBase article of ours [reproduced above].

It brings to mind the brilliant, though possibly untranslatable, remark by François Mitterrand about Jacques Attali: ‘Il a le guillemet facile.’

(6897)

Further to our ChessBase article on Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World by Brad Darrach (New York, 1974), we are grateful to Frank Brady (New York, NY, USA) for a copy of Fischer’s legal complaint (‘Demand for Jury Trial’, addressed to the United States District Court for the Central District of California). It was filed in 1975 against 27 parties, including Brad Darrach, Time Inc., Stein and Day, the United States Chess Federation, Burt Hochberg, Edmund Edmondson, Frank Skoff, Martin Morrison and Leroy Dubeck.

The ‘Plaintiff in pro ter’ was recorded as ‘Robert James Fischer, 300 Mockingbird Lane, South Pasadena, California. Tel: 795 5181’. He demanded a jury trial for his ‘complaint for defamation, invasion of privacy and interference with contractual relations’. The document, filed under 28 USC Section 1332, was 24 pages long and had two annexes (exhibits). These comprised advertisements reproduced from the United States Chess Federation’s magazine [such as the first illustration in our present feature article and the following]:

Chess Life & Review, September 1975, page 603

With much textual repetition the cause of action fell into eight sections:

‘... All such charges, references, assertions and imputations were false, malicious and unprivileged, and were calculated to and did expose Plaintiff to hatred, contempt and ridicule, causing him to be shunned and avoided and proximately caused him to sustain severe nervous shock and strain, and to suffer great mental anguish, humiliation, shame and embarrassment.

As a direct result of the foregoing, Plaintiff has suffered general damages in the amount of $20 million US dollars.

As a further result of the foregoing, FIDE Delegates who would have voted in favor of amending the FIDE world championship rules in accordance with Plaintiff’s requests after reading the ad in Chess Life & Review lost respect for Plaintiff – did not vote in favor of Plaintiff’s amendments, and as a result Plaintiff was precluded from amending the rules for the FIDE world championship match scheduled for about June 1975 in Manila, Philippines, did not compete in said match and consequently was damaged in the amount of $4 million US dollars.

As a further result of the foregoing conduct of Defendants on or about 1 April 1975 Plaintiff was stripped of his prestigious FIDE world chess champion title and thereby damaged greatly in his reputation, property and business interests, as governments, chess organizers, individuals and corporations who would have employed Plaintiff now would not and Plaintiff has suffered damages in the amount of $16 million US dollars.’

In each of the eight sections the sum of $20 million US dollars was claimed against ‘each and all of the Defendants’, and there was also a request ‘for costs incurred and such other further relief as the court may deem just and proper under the circumstances’.

The fate of Fischer’s complaint is related in our above-mentioned ChessBase article.

(6982)

Concerning the court case, see too page 216 of Endgame by Frank Brady (New York, 2011).

Some observations by Burt Hochberg on page 299 of the May 1975 Chess Life & Review:

(9095)

C.N. 4797 mentioned that Darrach also wrote on music, and his output included monographs about Beethoven and Verdi:

On the subject of New in Chess and the importance of factual accuracy, we turn to an article entitled ‘Facing Bobby Fischer’ by Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam on pages 12-27 of the 3/2015 issue [which praised Brad Darrach’s book highly]. It refers to the large amount of ‘unsettling’ material in Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair edited by Alessandra DeLucia (Darien, 2014) and argues that ‘even to this day, many Fischer fans and people that had known him personally are looking for ways to excuse his outrageous behaviour or gloss over his dark side’ (page 12). The dark side is identified as Fischer’s mental illness and virulent anti-Semitism, and page 16 states that ‘since the book appeared one year ago, it has been surrounded by silence’.

That last remark comes from a lengthy paragraph which, bafflingly, criticizes us for such silence. To quote just the conclusion:

‘It is remarkable that Winter, a historian who loves unearthing historical titbits, often fairly insignificant and from obscure sources, could not find more than a number of unpublished training games in Triumph and Despair to show to his readers. It is hard to come up with another reason than that he had no wish to enter the dark recesses of the mind of a man he admires so much as a chess player.’

Mr ten Geuzendam is referring to C.N. 8634 and, wilfully or not, he omits the obvious explanation for our ‘silence’: by that time we had already discussed Fischer’s dark side on many occasions, on the basis of earlier volumes by Mr David DeLucia.

Below, for instance, is an extract from C.N. 6189, concerning Bobby Fischer Uncensored (Darien, 2009):

Another item in Mr DeLucia’s collection, dated 18 November 1997: ‘a 100-page working typescript by Fischer entitled “What Can You Expect from Baby Mutilators”’.

Numerous illustrations are of books and other publications owned by Fischer, including such titles as The White Man’s Bible, The World Conspiracy and The Myth of the Six Million. His personal notebooks are also reproduced, and it would be impossible to overstate the anti-Semitism with which they are suffused. ‘Hitler was right about the Jews: They want to steal everything I’ve worked for all of my life’ (page 244). On page 285 another note, dated 21 May 1999, is also typical: ‘It’s time for programs against Jews and it’s also time for vigilante killings of Jews – random killings of Jews.’ Page 301 has a draft letter which begins:

‘Dear Mr Osama bin Laden allow me to introduce myself. I am Bobby Fischer, the World Chess Champion. First of all you should know that I share your hatred of ...’, etc., etc.

Mr DeLucia presents such material without editorial comment, rightly leaving readers to supply their own revulsion.

We also wrote about David DeLucia’s collection, again stressing the dark side of Fischer, in an article at ChessBase.com in 2012. The same year the feature article A Letter from Bobby Fischer to Pal Benko was posted, again courtesy of Mr DeLucia. We first mentioned the letter to Benko in C.N. 3165 (‘Fischer on Hitler’ – see pages 329-330 of Chess Facts and Fables) following publication of David DeLucia’s Chess Library: A Few Old Friends (Darien, 2003).

Another article, Instant Fischer, has an Afterword written in 2005, and its conclusion provides further proof that we have not shied away from denouncing Fischer:

From the late 1990s onwards he gave a series of radio interviews in which, egged on by standardless ‘broadcasters’, he came out with the most abject set of utterances ever made by a chess master.

(9245)

A retraction and apology are awaited from Mr Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam over his claim on page 16 of the 3/2015 New in Chess that we have been silent about Fischer’s dark side. As demonstrated in C.N. 9245, the truth is the exact opposite: thanks to Mr David DeLucia’s generosity, we have quoted extensively from the series of books which he and his daughter have published over the past dozen years, and much ‘dark’ material has been included.

A further example of non-silence is our conclusion to a ChessBase.com article in 2010:

The extent of Fischer’s depravity, anti-Semitism and, it must be said, apparent insanity was shown when a selection of his personal notes and other memorabilia was reproduced in Bobby Fischer Uncensored by David and Alessandra DeLucia (Darien, 2009).

(9252)

Despite the rebuttals in C.N.s 9245 and 9252, the 4/2015 issue of New in Chess contains no apology or retraction regarding Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam’s false statement in the previous issue that we have been silent over the dark side of Fischer shown in the documentation which David DeLucia has published from his collection.

Page 16 of the 3/2015 New in Chess. The section with the false attack on us is marked.

The truth is the exact opposite of what New in Chess readers were told, given that we have quoted far more ‘dark’ material from Mr DeLucia’s books than all other chess writers combined.

Before publication of his Fischer article in the 3/2015 New in Chess, Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam sent a preview to Mr DeLucia and was specifically told, in advance of publication, that his intended criticism of us was unfounded. Mr DeLucia has informed us:

‘When he sent me the draft the one comment I made was that he was wrong with his assessment of your view on Fischer. I told him to review past C.N. articles as I knew you had done a number of them regarding Bobby and his craziness. Dirk Jan obviously had a different view.’

(9338)

Addition on 15 June 2016:

Mr DeLucia’s next sentence in his above-mentioned e-mail message to us (13 May 2015) stated with regard to Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam:

‘There is no doubt that anyone who has followed C.N. and read his Fischer article knows that he is simply wrong on his assertions.’

On 20 June 2015 David DeLucia wrote to us regarding Mr ten Geuzendam:

‘My take on this was that he didn’t care what you wrote in past articles but wanted to get his view out there in NIC.’

Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam still cannot bring himself to correct the record in New in Chess after cold-bloodedly deceiving his readers about us on page 16 of the 3/2015 issue.

(9401)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘As New in Chess did not correct the record off its own bat, I sent the magazine this letter:

“Concerning page 16 of the 3/2015 New in Chess, Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam’s criticism of Edward Winter for disregarding the dark side of Fischer (as shown in published items from David DeLucia’s collection) is unfounded. Winter’s article Brad Darrach and the Dark Side of Bobby Fischer demonstrates that the truth is the exact opposite: in his Chess Notes column over the years, Winter has posted, courtesy of DeLucia, a large amount of such ‘dark’ Fischer material (more than all other chess writers combined, in fact). Moreover, DeLucia states that when he was sent a preview of the New in Chess article he specifically told Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam, prior to publication, that the planned criticism of Winter was wrong.”

My letter has not been published.’

(9635)

Addition by Mr Urcan on 30 May 2016: ‘In an e-mail message dated 4 November 2015 Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam told me that he would publish my letter. He has not done so.’

We are very grateful to Olimpiu G. Urcan, who is unflinchingly scrupulous.

From page 287 of Bobby Fischer Uncensored by David and Alessandra DeLucia (Darien, 2009) we reproduce a note by Fischer dated 8 July 1999:

‘The Jews claim that I’m mentally ill but they’re the ones who are mentally ill. What terrible hatred inside of them compelled them to forge an illegal mating variation in the Batsford edition of “My 60 Memorable Games” in my game with Bolbochan. And in the 1988 Faber and Faber edition of “My 60 Memorable Games” what compelled them to forge “winning the Bishops pawn” rather than what I really wrote “winning the two Bishops”. They’re the ones who are mentally ill!!!’

(6214)

For the full item, see also Fischer’s Fury.

The first section of a contribution from From Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA) in C.N. 9812:

‘Fischer can be seen playing 29...Bxh2 at the 1’00” mark of a video from the NBC news archives. The moments of play shown are not necessarily sequential; for example, the bishop already stands on h2 at 0’42”. Some of the subsequent play (33 Kg2 hxg3 34 fxg3) can be seen at 1’10” of another video.

From the NBC item it appears that Spassky was away from the board when 29...Bxh2 was played, a circumstance which casts doubt on any descriptions of his supposedly surprised reaction to the move. For example, on page 172 of Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World (New York, 1974) Brad Darrach wrote:

“Spassky jolted like a man hit by a bullet and stared at the board.”

Page 92 of Fischer/Spassky: The New York Times Report on the Chess Match of the Century mentioned the “look of incredulity” on Spassky’s face, said to be noticed by an audience member with binoculars.’

Our feature ‘Brad Darrach and the Dark Side of Bobby Fischer’ summarizes the dispute about Darrach’s book Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World (New York, 1974) on pages 299-300 of the May 1975 Chess Life & Review, a dispute which concerned three pieces in the New York Times Book Review:

13 October 1974, page 6: a review by D. Keith Mano of the Brad Darrach and George Steiner books on the 1972 Spassky v Fischer match;

17 November 1974, page 59: a letter to the Editor from Burt Hochberg, which is reproduced in the May 1975 Chess Life & Review;

23 February 1975, pages 41-42: a letter to the Editor from Brad Darrach in response to Hochberg. Extracts were reproduced, and disputed, by Hochberg in the May 1975 Chess Life & Review.

See also the many references to Darrach indexed in Bobby Fischer and His World by John Donaldson (Los Angeles, 2020). These include, on page 493, a brief comment that Darrach’s above-mentioned letter was ‘the only public response by Darrach after the book’s publication’.

Donaldson added:

‘Darrach shows no feelings of remorse in his lengthy defense to charges by Frank Brady and Burt Hochberg that he betrayed Bobby’s confidence and put words in his mouth. Nor does he comment about breaking his agreement with Fischer.’

It should, however, be noted that such charges did not appear in the Hochberg letter to which Darrach was replying.

We add here some significant passages in Darrach’s letter (sent from Madison, CT, USA) in the New York Times Book Review which were not quoted in Chess Life & Review:

‘The world of chess is like the Chinese court in the story of “The Emperor’s New Clothes”. The Emperor, Bobby Fischer, wanders about in a strange condition but nobody dares to say what everybody can see. In private, chess people tell grotesque or funny stories about their encounters with Mr Fischer; in public, they butter him up. “We don’t dare to offend Bobby”, one chess official told me. “He might quit the game, and chess without Bobby would be about as popular as tiddlywinks.”’

‘I take it Mr Hochberg thinks the subhumanity is overstressed in the book. I can only say it was overstressed in the man I wrote about.’

‘But Mr Hochberg will say I imply interpretations and judgements of Mr Fischer in my choice of incidents. I can only say I tried to let the events speak for themselves. If I have anywhere redressed reality, it is only to omit dozens of scenes which, in aggregate, would have made Mr Fischer seem weird beyond belief – as in fact he sometimes was.’

‘During the 13 months before the Reykjavik match, on assignments from Life Magazine, I visited Bobby, on the average, twice a week, usually for five or six hours at a stretch; sometimes I saw him every day for eight or ten days in a row; when I did not see him we spoke by telephone sometimes five or six times a week. I saw him in New York, in Buenos Aires, at his training camp in the Catskills. I saw him in a hundred moods and circumstances – happily scoffing up platefuls of Chinese food, terrified in the back seat of a small plane, red-eyed with rage as he kicked a photographer in the shins, laughing as he romped with a collie in the open pampas, guffawing at Red Skelton on TV in a New York hotel room, casually playing fast chess in an East Side steak house as he tunneled into a two-inch thick New York Cut, lying limp with a bad cold in a stuffy little cell at Grossinger’s.

In Iceland, as the book makes clear, I saw him every day and often most of the night for more than two months.’

‘If my “viewpoint is severely limited” I’d like to see the man who could stick with Mr Fischer long enough to develop a broader one.’

‘Mr Hochberg is apparently interested in what the match revealed about Mr Fischer’s chess; I am more interested in what the match revealed about Mr Fischer.

It revealed, among other things, such murderous force that I find myself smiling at Mr Hochberg’s attempts to protect Mr Fischer from my book. The only thing Mr Fischer needs to be protected from is Mr Fischer. Drifting in fantasies, chased by terrors, rigidified by pride, impelled to self-destruction, he will be very lucky if he can survive his own character long enough to defend his title against Anatoly Karpov. If he can beat that truly formidable young Russian, we may begin to believe he belongs with the supreme masters, Steinitz and Lasker and Botvinnik, who attained the pinnacle and held it. If he welshes on the match he will be remembered as a half-mad maverick who could produce great games and even great years, but lacked the will and the principle to sustain a great career.’

(12037)

John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) has sent us a copy of a telegram from Brad Darrach to Bobby Fischer:

‘Robert J. Fischer

Hotel Loftleidir

Reykjavik, IcelandDear Bobby,

I want to thank you for the series of exclusive interviews I have had with you, and, through your good offices, with your team members, during the past several months.

As we have discussed, I affirm my agreement that I will not use this material for a book or for any magazine article without first obtaining your written approval. Of course, my present series of articles for Life Magazine is exempted from the need for this prior approval.

I look forward to a long and close relationship with you.

Sincerely,

Brad Darrach’

The text was given on page 492 of our correspondent’s book Bobby Fischer and His World (Los Angeles, 2020), introduced as follows:

‘Darrach’s duplicity is documented in a telegram sent during the match.’

Wanted: confirmation of the exact date on which Darrach sent it.

(12049)

Addition on 2 November 2024:

It seems likely to us that the telegram was sent on 4 September 1972, a tentative conclusion also reached by Rudy Bloemhard (Apeldoorn, the Netherlands):

Many virtually identical (agency) obituaries of Brad Darrach appeared in the US press, such as the following on page 8 of the Daily Times (Salisbury, MD) on 7 November 1997:

However brief, references to chess in the mainstream media traditionally have a factual mistake or two. In the penultimate paragraph above, 1976 should read 1974.

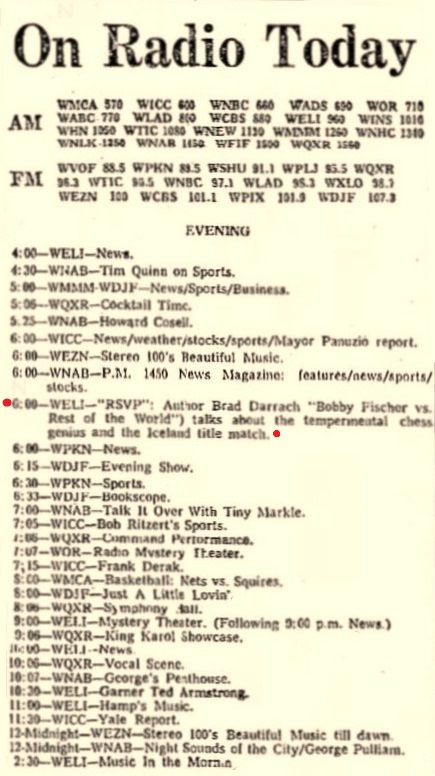

One broadcast by Darrach, on WELI 960, can be noted from that year, as listed on page 75 of the Bridgeport Post, 26 December 1974:

John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) informs us that he is continuing to investigate Brad Darrach’s Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World (New York, 1974), and at this stage we quote the following from him:

‘The New York bookseller Fred Wilson, active since the 1970s, has mentioned to me that the book never sold particularly well among the chess community. He believes that it was marketed to the casual player who had taken up the game during the Fischer boom of the early 1970s. Anthony Saidy has told me that what most stood out to him after reading the book was Darrach’s habit of including himself in conversations where he was not present. Frank Brady has made the same observation. On the basis of how he and his family were portrayed, Saidy estimates that approximately 20% of the book was fabricated.’

We add some jottings of our own. Although published in mid-1974, the book was not mentioned in Chess Life & Review (apart from the January 1975 advertisement shown in our feature article) until the May 1975 issue, in which Fischer’s removal as world champion also happened to be reported. The book was listed as being on (direct) sale to USCF members only once, in the August 1975 issue (with a members’ discount of 70 cents). Fischer’s lawsuit was announced in the October magazine, and there are no sightings of the name Brad Darrach in Chess Life & Review in 1976.

It is of interest to note some of the attention that Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World received in newspapers of the time.

In October 1974 an Associated Press report (sometimes attributed to Dan Berger, and with apparent input from Darrach) was published in dozens of US newspapers. On newspapers.com many appearances can be found by searching for this paragraph:

‘Fischer is the second American ever to hold the title, which must be contested every three years. The first was Alexander Alekhin in 1937.’

Few lengthy reviews have been found, but a notable critic of the book was R.E. Fauber (1936-2013). On page 41/9 of the Sacramento Bee, 23 March 1975 he observed:

‘Darrach is one of your usual kind of slick journalist types who were pampered in English 1a while in college. He happily quotes Fischer’s description of him as a “pretty awful” chessplayer. His ignorance of chess spills over onto every page of the book.

... If you like books about fearful hysterics and do not play chess well, you will love Darrach’s.’

If Darrach’s ignorance of chess ‘spills over onto every page of the book’, a few examples might be expected, but Fauber preferred generalities, as in the concluding paragraph:

‘In fairness to Darrach, he was up close for most of the drama of the Fischer-Spassky match, which he chronicles in the book. He seems a careful reporter, but his consummate ignorance of what competitive chess is about disqualifies the tone and connotative value of the book. If you must read it, get it at the library.’

Fauber returned to the book on page 23 of the 22 June 1975 edition of the same newspaper, writing ‘Then there is the even more execrable product of rank and reeking amateurs such as Brad Darrach’s Bobby Fischer vs the Rest of the World’ and calling it ‘that hysterical essay’.

A lengthier article on Darrach’s work, by Juan Rodriguez (1948-2024) on page 34 of the Montreal Star, 29 March 1975, took a very different view: the book was ‘absorbing – and hilarious’. The concluding paragraph by Rodriguez (‘the Montreal Star’s rock music critic’):

‘Even if you’ve never heard of Bobby Fischer, this book will make you laugh for hours.’

The review gave the publisher as McCraw-Hill Ryerson, and not Stein and Day.

The longest review that we have found is by Martin Johnston (1947-90) on page 13 of the ‘Weekend magazine and book reviews’ section of the Sydney Morning Herald, 15 February 1975. Some extracts:

‘There is a small and curiously interesting class of books whose authors give the impression of being, on the one hand, the only people qualified to write on a particular subject and, on the other, quite incapable of doing so. This book is one of them. While I quake at the thought of Mr Darrach (whose apprenticeship was ten years as film reviewer for Time, which to me speaks for itself) writing on anything, I have to admit that the very qualities that make this book so unpleasant may well be those best qualifying the author for admittance to the confidence of the monstrous genius Fischer.

Fischer, as even non-players are generally aware, is not a lovable man. We tend, of course, to make allowances for genius in the spirit of Auden’s elegy on Yeats: “You were silly like us; your gift survived it all.” To describe Fischer’s oddities of character as merely “silly” seems, by contrast, risibly inadequate.’

‘... What Darrach does, much more than Fischer’s affable biographer Frank Brady, is to bring the reader brutally face to face with the private figure – lonely, insecure, arrogant, an almost inarticulate genius with the culture of a gum-chewing bovver boy and the social feelings of a warthog – behind the public antics.’

‘He [Darrach] provides lurid snaps of Fischer in paranoid terror of Soviet Machiavellianism; Fischer as inconsiderate lout; Fischer as idiot savant – anything, indeed, rather than try to capture what Fischer is and why.’

‘... Darrach can’t write, except the nauseating hip prolixities of the New Journalese.’

‘...Darrach’s book (despite one additional deficiency – an apparent inability to distinguish between fact, speculation and gossip) is unavoidably fascinating, because of its subject, and Darrach’s proximity to him; but it hardly deserves to be.’

‘... So why buy Darrach? Well, out of place though his smug trendiness is in this company [the previous paragraph praised other writers, singling out Purdy], he is the only one to show us Fischer with the defences down, as one grotesque to another. I hate recommending it but I have to: if you like Bosch or Grünewald, you’ll love this.’

The final quote on the back cover of Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World was ‘We owe a debt to Darrach’. That was from an article by Burt Prelutsky (1940-2021) on page 16 of the ‘Calendar’ section of the 5 January 1975 edition of the Los Angeles Times:

‘Asked what impressions he retains of his three months in Reykjavik, Darrach says, “It was like being in the trenches. For weeks on end, I averaged no more than an hour’s sleep a night. I was up all day, reporting the event for Life, and then Bobby would insist on keeping me awake all night, talking. I was strained to the breaking point, and ended the summer on the verge of a nervous breakdown. My muscles never totally recovered from the ordeal. It wasn’t just the physical abuse, though. Being with Bobby is like being with a robot on some dumb TV show, pretending to conduct rational dialogues. He is a totally frozen person. The only time you could make him happy and get a spontaneous reaction from him was if you told him about a disaster. Tell him about an earthquake or a plane crash or an outbreak of the plague, and he couldn’t help smiling. Psychologically, as his sister says, he’s a three-year-old child; he’s a mess. He is a man consumed with hatred. He speaks of destroying his opponents with brute force. To win is never enough, he also must humiliate. Chess, at Fischer’s or Spassky’s level, is aggression at the outermost extreme.”

I asked Darrach whether he had ever dared challenge Fischer. “We’ve played a few times. And although I am what Bobby refers to with contempt as a weaky and he obviously wasn’t going all out, they were brutal experiences. His concentration is so total that it hits you in waves of force. After a while you can hardly breathe.”

We owe a debt to Darrach. Like such fearless correspondents as Richard Harding Davis and Sir Henry Stanley, he has ventured forth to where only the bold, the brave and the loony would dare set foot. He has not written a book about chess or even just a book about chessplayers, exactly. What Darrach did, like a latter-day Ernie Pyle, was to file blood-stained dispatches from Reykjavik, the unlikely site of World War II½.’

(12066)

See too: Articles about Bobby Fischer.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.