Edward Winter

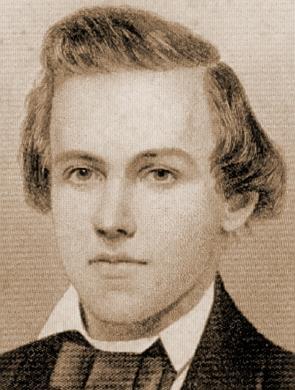

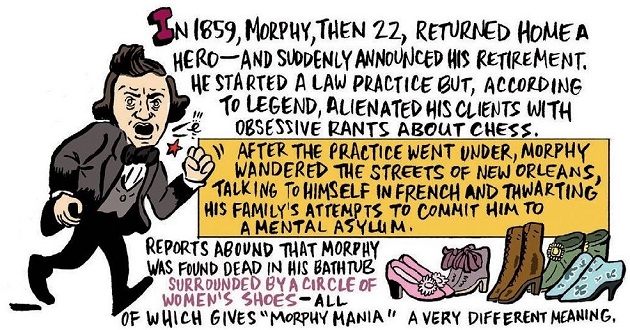

In a prize quiz set by Raymond Keene on page 99 of The Spectator, 19-26 December 1987 readers were asked, in a section entitled ‘They’re all mad’, which player died in his bath surrounded by women’s shoes. With predictable fallibility, Raymond Keene gave Morphy as the answer (on page 51 of the 23 January 1988 issue).

Page 144 of 2010 Chess Oddities by Alex Dunne (Davenport, 2003) condensed Morphy’s life into half a page but still found space to assert, ‘he arranged women’s shoes in a semicircle around his bed’.

The Morphy/shoes story was discussed on page 305 of David Lawson’s biography of Morphy and on page 162 of Chess Explorations. Over the years much embroidery (e.g. ‘women’s shoes’) has been grafted onto what appeared in the earliest known sighting of the Great Morphy Footgear Affair (i.e. on page 38 of the 1926 booklet Life of Paul Morphy in the Vieux Carré of New-Orleans and Abroad by Regina Morphy-Voitier). Morphy’s niece wrote:

‘Now we come to the room which Paul Morphy occupied, and which was separated from his mother’s by a narrow hall. Morphy’s room was always kept in perfect order, for he was very particular and neat, yet this room had a peculiar aspect and at once struck the visitor as such, for Morphy had a dozen or more pairs of shoes of all kinds which he insisted in keeping arranged in a semi-circle in the middle of the room, explaining with his sarcastic smile that in this way, he could at once lay his hands on the particular pair he desired to wear. In a huge porte-manteau he kept all his clothes which were at all times neatly pressed and creased.’

This innocently unenthralling story (about how Morphy arranged his own shoes) subsequently passed through many hands, such as Reuben Fine’s (The Psychology of the Chess Player, page 38):

‘... another eccentric habit of arranging women’s shoes in a semi-circle in his room. When asked why he liked to arrange the shoes in this way he said: “I like to look at them”.’

On page 16 of Idle Passion (New York, 1974) Alexander Cockburn declared that Morphy died ‘according to some accounts, in his bath, surrounded by women’s shoes’.

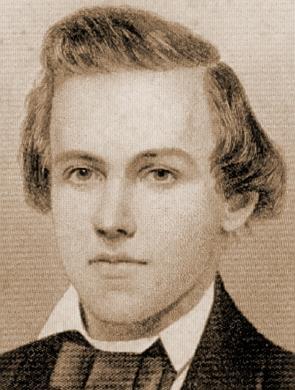

In Time, 17 February 1975 Brad Darrach wrote:

‘Paul Morphy he [Cockburn] reminds us, was a paranoid fetishist … who liked to stand ecstatically in a circle of women’s shoes.’

And so it is that much of chess history is not history at all but lurid figments. Anyone criticizing such output risks being labelled a spoilsport or humourless pedant, but a far heavier price is paid by our game’s greatest practitioners, for they are condemned to star ad infinitum in seedy anecdotes which are the product of mindless inter-hack copying or brutal distortion. Any aspect of their lives is considered fair game for sheep and jackals alike, this being the time-honoured process whereby chess history is made ‘fun’.

Paul Morphy

(2913)

C.N. 5280 discussed Treasure Chess by Bruce Pandolfini (New York, 2007) and quoted from page 264:

‘Paul Morphy did various inexplicable things, such as placing women’s shoes in a semicircle around his bed before going to sleep.’

(2913)

Some observations by Burt Hochberg on page 299 of the May 1975 Chess Life & Review:

Here is the full text of the above-mentioned item (C.N. 1271) on page 162 of Chess Explorations:

From James J. Barrett (Buffalo, NY, USA):

‘We all know that in his The Psychology of the Chess Player (page 38, Dover edition), Reuben Fine speaks of Morphy arranging a semicircle of women’s shoes in his room; “When asked why he liked to arrange the shoes in this way he said: ‘I like to look at them.’” As Lawson comments in his book, “the story has grown”. An example: reviewing Cockburn’s Idle Passion in Time (17 February 1975) Brad Darrach wrote: “Paul Morphy he [Cockburn] reminds us, was a paranoid fetishist who ... liked to stand ecstatically in a circle of women’s shoes.” I could cite other journalistic trash articles of the same ilk. But what are the facts? I can state with authority that David Lawson, in all his researches, could never trace any anecdote regarding Morphy and shoes any earlier than the 1926 booklet by his niece Mrs Morphy-Voitier, where it was stated clearly that Morphy arranged his own shoes in a semicircle in his bedroom, and that when asked about it explained that in this way he could easily select the pair he wished to wear. This leaves it up to Dr Fine to reveal his source for his version of the anecdote.’

For the record we quote Cockburn’s exact words on Morphy (page 16): ‘At the age of 47 he caught a chill and died – according to some accounts, in his bath, surrounded by women’s shoes.’ And page 47: ‘His voyeurism was gratified by the opera and the business of the women’s shoes.’

In Time, 31 July 1972, Ray Kennedy was the author of the cover article on pages 32-37 of that issue – a catchpenny thing ‘The Battle of the Brains’ which was mainly about Spassky and Fischer but also leapt gleefully on whatever might serve to ridicule such great players of the past as Morphy, Steinitz and Alekhine. For example (from page 35):

‘Morphy was given to such eccentricities as arranging women’s shoes in a semicircle in his room and prancing around his veranda reciting in French that “the little king will go away unabashed” [sic – an apparent miscopying of ‘all abashed’].’

In short, yet another ‘Fun’ writer for whom Reuben Fine’s The Psychology of the Chess Player was a godsend.

(5559)

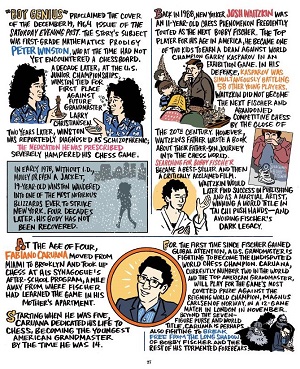

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) draws attention to a cartoon feature on pages 26-27 of the November-December 2018 Playboy: ‘American Chess Masters’ written by Brin-Jonathan Butler and illustrated by Nathan Gelgud.

The left-hand section on Morphy refers to ‘a spooky child prodigy’ who later ‘traveled across Europe and toured royal courts ...’ Then comes this ‘Fun’:

The treatment of Steinitz does not even attain the ‘according to legend’ and ‘reports abound that’ level:

(11084)

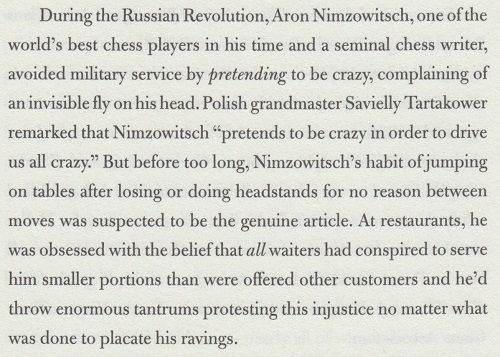

An extreme example of a chess book treating the leading players of the past without respect is The Grandmaster by Brin-Jonathan Butler (New York, 2018). From page 133, this is the sum total (Wikipedia-based, of course) of what the book offers on Nimzowitsch:

An extract from C.N. 891, concerning Total Chess by David Spanier (London, 1984):

In a sense we could repeat our comments on the Eales work (C.N. 878): Total Chess’s main attraction is that it is clear and sensible (whilst also conveying what might be labelled the ‘excitement’ of current chess). It too is less good on individuals than on tendencies – once again (page 146) poor old Wilhelm Steinitz is ridiculed for alleged hallucinations that Mr Spanier is happy to mention but would be unable to corroborate. The temptation to add piquancy and colour to chess books is so great that few authors can stop themselves from repeating ‘good’ stories, even if not a shred of evidence exists to support them. As noted before in this magazine, we deplore such a ‘masters are fair game’ attitude.

From page 79 of the 2002 edition of Chess Lists by A. Soltis:

‘The most tragic case belongs to Paulino Frydman, a little-known Polish master who was invited to the Bad Podĕbrady, Czechoslovakia international of July 1936. Surrounded by several world-class players – including Alexander Alekhine, Salo Flohr, Erich Eliskases and Gideon Stahlberg – he astounded them by allowing only a draw in his first seven games. But two rounds later, with a score of 8-1, he lost to Alekhine and suffered a nervous breakdown. Frydman scored only one and a half points in his last eight games and finished as an also-ran. He was never again a significant figure in chess.’

There were similar words from Sourceless Soltis on page 81 of the 1984 edition of his book. In reality, though, from the field of 18 masters Frydman finished equal sixth with Eliskases, and his significant over-the-board achievements in subsequent years are a matter of public record. As regards the ‘nervous breakdown’ part of the story, it may be wondered if Soltis had any solid information of his own or was merely copying from Wolfgang Heidenfeld’s entry on the Podĕbrady tournament in The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977).

Next, a typical Internet item by Bill Wall:

‘Frydman, Paulino (1905-1982)

A leading Polish player during the 1930s who represented his country in seven Olympiads. He used to run around nude in hotels yelling, “fire”.’

Wall writes similarly at another website:

‘Paulino Frydman was a leading Polish player during the 1930s who represented his country in seven olympiads. He used to run around nude in hotels yelling “fire”.’

Or again:

‘The Polish master Frydman also ran around nude, but usually in hotels while yelling, “fire”.’

At yet another Internet site, Wall disseminates a slightly dressed-up version of his story:

‘The Polish master Paulino Frydman represented his country in seven chess olympiads. He liked to clear out hotels by running down the halls in his underwear yelling, “Fire!”’

At no stage, of course, has Wall given any further particulars, but a similar tale may be recalled from The Psychology of the Chess Player by Reuben Fine. On page 65 he wrote:

‘During a chess tournament in Poland a Polish master by the name of A. Frydman was reported to have gone berserk and to have run through the hotel without any clothes on shouting “Fire!”’

This may seem strange. We have been repeatedly assured by Wall that the master in question was Paulino Frydman, so why did Fine write ‘A. Frydman’? Moreover, Fine suggests that the incident in question occurred once only, whereas Wall is ostensibly privy to information that it was Frydman’s frequent conduct (i.e. what he ‘used to’ do, ‘liked to’ do and ‘usually’ did). Finally, given that Podĕbrady was in Czechoslovakia and not Poland, where Fine places the tournament in question, how might any of this tie in with Soltis’ reportage?

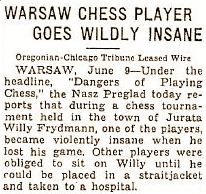

We note that page 44 of CHESS, 14 October 1937 contained the following piece under the heading ‘What really happened?’:

‘Variations of the following weird theme have appeared in a number of British and American newspapers. We reproduce without comment:

“In a chess tournament at Jurata, Poland, a contestant, Willy Frydmann, lost a game then went raving mad.”’

So now we have ‘Frydmann’ instead of ‘Frydman’ and ‘Willy’ rather than either ‘Paulino’ or ‘A’.

Pages 197-198 of the July 1937 Deutsche Schachzeitung had a brief account of the Jurata tournament, a 22-man contest in May/June for the Polish championship. It was won by Tartakower ahead of Ståhlberg and Najdorf, and the Deutsche Schachzeitung stated that P. Frydman finished last but two, with 6½ points, having withdrawn after losing in the 15th round and suffering a nervous breakdown. (‘Frydman erlitt, als er in der 15. Runde verlor, einen Nervenzusammenbruch und musste aus dem Turnier ausscheiden.’)

However, the full crosstable of Jurata, 1937 was given on page 374 of the December 1937 Wiener Schachzeitung, and it stated, correctly, that the player who finished 20th was A. Frydman. Earlier (page 152 of the May 1937 issue) the Wiener Schachzeitung had named the player as Achill Frydman and had referred to ‘den tragischen Unfall Achill Frydmans, der mit einer schweren Nervenerkrankung in eine Heilanstalt überführt werden musste’.

Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia lists ‘Achilles Frydman (1905-circa 1940)’, a player with an entry on page 276 of Szachy od A do Z by W. Litmanowicz and J. Giżycki (Warsaw, 1986). Perhaps a Polish correspondent can locate further details. And perhaps – a true long shot, this – one or two writers will consider it appropriate to substantiate their assertions about Paulino Frydman. For our part, we have found no contemporary report mentioning fire, nudity or underwear.

(2917)

From Tomasz Lissowski (Warsaw):

‘It is true that Achilles Frydman of Łódź (and not the more famous Paulin(o) Frydman of Warsaw, and later of Buenos Aires) had serious health problems in the late 1930s. Two quotations follow, the first being from the column in Polska Zbrojna by Colonel M. Steifer at the time of the Jurata, 1937 tournament:

“Najdorf could have easily won first prize, had it not been for an irritating incident with A. Frydman, who caused many difficulties for the tournament management and for the players. This cost Najdorf two points: the games he lost against Gerstenfeld and Schächter in winning positions.”

Further information is given by Tadeusz Wolsza on page 32 of the third volume of his dictionary of Polish chess players, Arcymistrzowie, mistrzowie, amatorzy (Warsaw, 1999):

“Near the end of the tournament Achilles Frydman fell ill. After one of his numerous lost games he was the victim of a strong attack of fury, and doctors placed him in a mental asylum in Kocborowo. This unfortunate case ended his chess career. He never returned to competitive chess, and his occasional off-hand games were only against friends.”’

(2932)

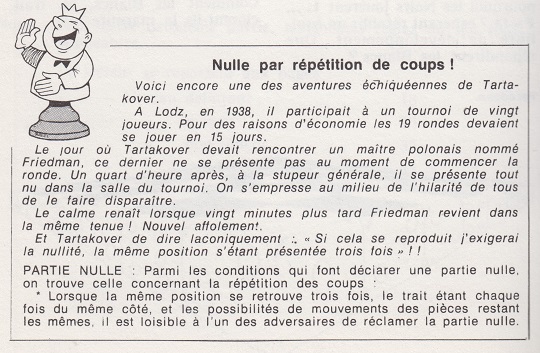

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) refers us to page 10 of the eighth issue of the Spanish magazine Ocho x Ocho Especial (January 1995), in which Román Torán quoted Albéric O’Kelly de Galway as stating that at Łódź, 1938 ‘Friedman’, entirely naked, turned up 15 minutes late for his game against Tartakower. It is not specified where the Belgian master wrote the item attributed to him by Torán.

(3290)

C.N. 2917 (see above) quoted from page 44 of CHESS, 14 October 1937 the following piece under the heading ‘What really happened?’:

‘Variations of the following weird theme have appeared in a number of British and American newspapers. We reproduce without comment:

“In a chess tournament at Jurata, Poland, a contestant, Willy Frydmann, lost a game then went raving mad.”’

Russell Miller (Vancouver, WA, USA) has found one of those newspaper reports, on page 3 of The Oregonian, 10 June 1937:

Can a reader find what had appeared in the Polish publication mentioned (whose correct title is Nasz Przegląd)?

(7084)

Below is how half of page 66 of Objectif mat! by Raoul Bertolo and Louis Risacher (Paris, 1978) was filled:

(9370)

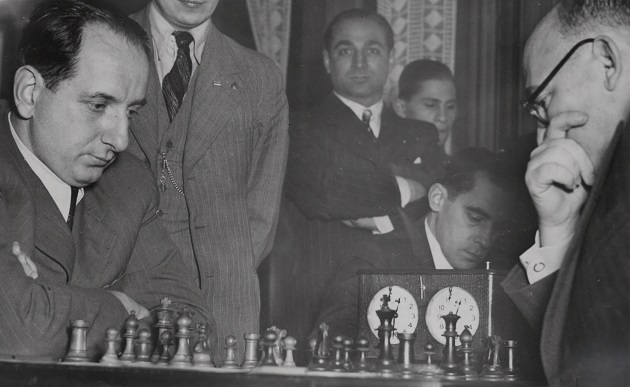

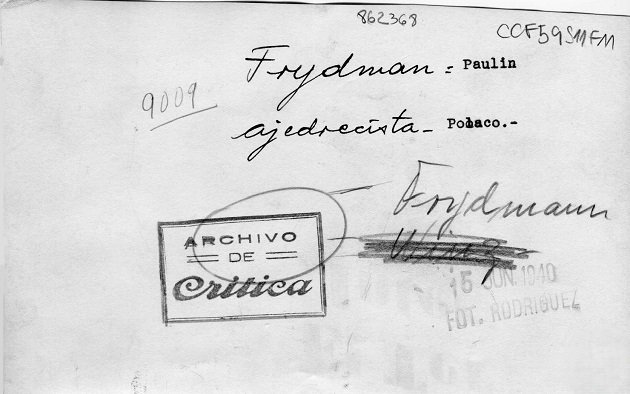

Courtesy of the Crítica archive, Olimpiu G. Urcan sends this photograph:

It will be recalled that Paulin(o) Frydman (White) has been the victim of negligence by chess writers so eager to have fun with insanity that they muddled him with a lesser-known, similarly-named player.

(12183)

George Koltanowski

Now we add the handling of the affair by Koltanowski, from an article entitled ‘People are the craziest!?’ on page 186 of Chess Digest Magazine, August 1971:

‘[L]et me start at the beginning of this true story:

We quote from the Jurata (Poland) morning paper of 11 August 1937:

“In the International Chess tournament of Jurata, 21 of the 22 competitors have suddenly become stark crazy. They have decided to continue with the tournament and finish their 21 games in 14 days. Only one participant was sensible enough to retire to a resthome.” End quote.

The player in question was Anton Frydman, a Pole who a few days before the start of the tournament, had just been released from a Mental Institute and had been warned by the doctors not to play chess for a good while. Yet Frydman persuaded the tournament organizers to allow him to play in the tournament. In the first rounds he played good chess. He managed to draw with Xavier Tartakower, who eventually won the tournament. But the way the chess masters played, NO adjournments, playing two games a day, almost each day, with a total of 12 to 14 hours of mental work daily, sometimes even longer, something had to give.

In the 12th round Frydman started his shenennigans [sic]! During his game with Miguel Najdorf, Frydman ran to the phone after every move, placing long-distance calls collect, ordering such important articles as a bicycle from Germany, a flute from Hungary, etc. The next day he had to be locked up in his room ... he insisted in walking around in the lobby in his Adam’s suit. Gideon Stahlberg, who had the misfortune of having the room next to Frydman, couldn’t sleep at night. His (opponent) next-door neighbor was calling out check and check-mate all night long in a very loud voice.

That was when the committee decided to have Frydman returned to his Resthome ... and the players met to vote if they should continue the tourney under those terrible long hour conditions. They finished the event!’

The ellipses in the above passage are Koltanowski’s.

What he terms ‘this true story’ is just a further example of the Koltanowski drivel-machine at full throttle. He did not participate in the tournament, and the origin of many of his claims is unknown to us. A number of them, however, are contradicted by the details in Four Polish Championships by T. Lissowski (Nottingham, 2003), which gives all available games from Jurata, 1937 and some background information (noting, for instance, that the tournament took place from 23 May to 6 June 1937 and that ‘three games were to be played every two days’). The following points, in particular, may be listed:

a) Although the tournament finished on 6 June, Koltanowski claims to be quoting a topical-sounding newspaper item which he dates over two months later: 11 August 1937. (It may seem ungracious to criticize Koltanowski on a matter where, for once, he attempted to cite a documentary source, but he failed even to name ‘the Jurata (Poland) morning paper of 11 August 1937’ from which he was purportedly quoting.)

b) Koltanowski refers to ‘Anton’ Frydman. His forename was Achilles.

c) Another incorrect statement by Koltanowski is that Frydman drew with Tartakower. In fact, Tartakower won (in round 2).

d) Koltanowski is also wrong to indicate that Frydman’s game against Najdorf was in the 12th round. They met in round 15.

e) Nothing has been found to support Koltanowski’s assertions about Frydman’s withdrawal from the tournament.

(3567)

See Chess and Insanity.

In 1976 Paul Schmidt wrote to Chess Life & Review to straighten out the following paragraph by Koltanowski which had appeared on page 89 of the February 1976 issue:

‘During the Second World War Dr Alexander Alekhine, then Champion of the World, participated in a number of tournaments. In 1942 he played in Prague, under the sponsorship of Germany’s Nazi Youth Association. There he met 18-year-old Klaus Junge of Leipzig, who was acclaimed as a future world champion by the German press, and who was stabbed to death in a chess club fight in 1942!’

On pages 212-213 of the April 1976 issue Schmidt wrote:

‘Klaus Junge, one of my best friends, was not “stabbed to death in a political brawl in a chess club in 1942” as stated by George Koltanowski in the February issue. He died in combat, as a German officer, on the last day but one [sic] of World War II, i.e. in 1945. Nor did Alekhine meet him for the first time at the tournament in Prague, 1942, where they tied for first and second place. They met for the first time at the 1941 tournament in Warsaw-Cracow, their individual game ending in a draw, … and then again in 1942 at the six-master double-round tournament in Salzburg, each winning one game… [as well as two other tournaments before Prague, 1942].

Klaus Junge also did not come from Leipzig. He was born in Chile as the son of German parents who, unfortunately, returned to Germany to get a better education for their children than was possible at that time in Chile – only to lose all their three sons to Hitler’s war. His parents lived in Hamburg.

About the only correct reference to Klaus Junge in Mr Koltanowski’s article is to his chess genius: had he not died in 1945 he would indeed have become a formidable contender for the world championship. He was equally fond of combinatorial and positional play, and his style was completely mature even at age 18. My book Schachmeister Denken! (Walter Rau Verlag, 1949) is dedicated to the memory of Klaus Junge.’

Photograph in the Prague, 1942 tournament book. Standing: K. Junge, J. Podgorný, J. Foltys, F. Sämisch, J. Rejfíř, C. Kende (organizer), F. Prokop. Seated: A. Alekhine, O. Důras.

(2926)

Anyone wishing to make chess history ‘fun’ by spreading unsubstantiated anecdotes and tittle-tattle has only to eschew specifics like dates and places and rely on the shadowy word ‘once’. From 2010 Chess Oddities by A. Dunne (Davenport, 2003) we scoop up the following selection:

‘World Champion Emanuel Lasker was once offered an opium scented cigar …’

‘Aron Nimzovich once broke his leg ...’

‘Aron Nimzovich once stood on his head ...’

‘Pal Benko once thought Mikhail Tal was trying ...’

‘Max Euwe once requested a game for the World Championship be postponed ...’

‘Akiba Rubinstein once won four brilliancy prizes in one tournament.’

‘Anatoly Karpov once listed his hobbies as ...’

‘Mikhail Tal was once signed to play the Devil in a movie ...’

‘Tal was once asked what chess piece he would like to be ...’

When an author (see C.N. 3255) who calls Harry Golombek Sir Henry Golombek ventures a one-sentence summing-up of the complex Morphy/Staunton affair the result is unlikely to be impressive. From pages 10-11 of The Sporting Scene by George Steiner:

‘The fairest assessment of this acid imbroglio would be that Morphy was justified when he asserted that Staunton was afraid to meet him across the board and that Staunton was using what influence he had to block the triumphant progress of a Yankee intruder.’

Given our admiration for the writing of Gilbert Highet it is no pleasure to quote from the article of his which was mentioned in C.N. 3232:

‘… the English dictator of chess, Howard Staunton, not only avoided a direct meeting with [Morphy], and refused to answer his letters, but snubbed him in the most brutal way, hinting in his chess column that Morphy was a crook who played chess as a method of swindling people out of their money.’

(3256)

An ‘intellectual’ writer who put no scholarship into his chess writing was Arthur Koestler. Pages 206-231 of his book The Heel of Achilles (New York, 1974) reproduced his (London) Sunday Times articles of 2 July 1972 and 3 September 1972. Below is a sample from pages 213-214 of the book:

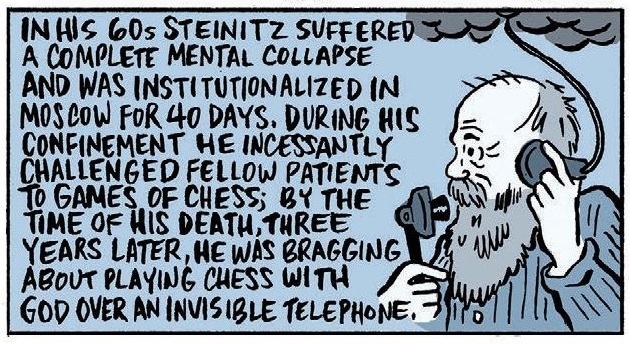

‘The great Alekhine, when beaten, often threw his king across the room, and after one important lost game smashed up the furniture in his hotel suite. Steinitz, on a similar occasion, vanished from his quarters and was found disconsolately sitting on a bench in a deserted park. He died insane. So did Morphy, who preceded him as world champion. Morphy suffered from persecution mania; Steinitz from delusions; he thought he could speak over the telephone without using the instrument and that he could move chessmen by electricity discharged from the tips of his fingers. What sane person could devise a symbol more apt for the omnipotence of the mind?’

(3266)

Bernard Levin was a British writer of the supposedly highbrow variety who, like Arthur Koestler and George Steiner before him (see C.N.s 3256 and 3266), occasionally wrote about chess, on autopilot, if a world championship match was in the news. We recently came across a piece by Levin on pages 171-174 of his anthology All Things Considered (London, 1988). Endowed with the catchpenny title ‘The mating game’, it had already somehow received space in the (London) Times, of 9 November 1987, and was the usual dollop of flash-fried offal served by writers who think that a readable overview of chess can be rustled up for the populace by cribbing tittle-tattle from books like Cockburn’s Idle Passion, Fine’s The Psychology of the Chess Player and Schonberg’s Grandmasters of Chess.

A prime objective of such output is to deride chess masters (particularly dead ones), and we quote just one passage from Levin’s ‘The mating game’, i.e. the sum total, ‘all things considered’, of what he had to impart about Emanuel Lasker:

‘Lasker, for instance, tried a variety of business schemes, all of which came to nothing (or to bankruptcy), his record being a pigeon-breeding establishment which failed, not surprisingly, because he tried to mate two male pigeons to get the thing properly started.’

The pigeon yarn is often seen, and in C.N. 1048, an examination of The Kings of Chess by W. Hartston (London, 1985), we commented:

‘The Lasker chapter captures the German champion vividly but still cannot resist churning out vague claims (page 81) about his “being swindled by all who did business with him”, trying to mate two male pigeons, despising imitation flowers, etc. (We might point out that Dus-Chotimirsky – Lasker & His Contemporaries, issue 4, page 140 – quotes Lasker as saying that he could not stand real flowers, but we have no wish to launch a debate on his floral tastes ...)’

When the unsubstantiated pigeon story about Lasker started circulating is difficult to say, but it was a staple feature of chapter 22 of Emanuel Lasker Biographie eines Schachweltmeisters by J. Hannak (Berlin-Frohnau, 1952) and chapter 21 of the English version, Emanuel Lasker The Life of a Chess Master (London, 1959). Since many parts of Hannak’s book read like a novelette, it may reasonably be felt that something more substantial is required before Lasker is mocked.

If any outsider is to cast an eye over chess and chessplayers, how we wish that it could be a truly outstanding writer with the finest insight, such as Alan Bennett.

(3662)

C.N. 11127 quoted the following from page 3 of the Chess Amateur, October 1925:

‘To the folly of the lay journalist writing about chess there is no end.’

In an item on Hans Frank, C.N. 5533 drew attention to some observations in the Preface (page 1) of Nuremberg. Evil on Trial by James Owen (London, 2006 and 2007):

‘History is the prelude to myth. When what actually happened, in all its unsimplified and usually unsensational truth, is forgotten, we create legends for ourselves. Frequently this is because the facts are not exciting enough, or not properly understood, or because they are uncomfortable to live with. ...

... if history has a value it is in reminding us that the past ought not be backlit and airbrushed for ease of mass consumption. That, as the Nazis knew, is not history but propaganda.’

C.N. 5574 asked which chessplayer Edgar Lustgarten described as being ‘the subject of more public discussion than any other English clergyman since Wolsey’.

The observation appeared on page 290 of Lustgarten’s book The Judges and The Judged (London, 1961), in his chapter on ‘The Rector of Stiffkey’, Rev. Harold Francis Davidson (1875-1937). Davidson’s ‘extra-rectorial activities’, to borrow the genteelism coined by Lustgarten, have been widely narrated. One of the lesser-known monographs is The Rector of Stiffkey and Morston by Buttercup Joe (Briston, 1985 and 1987):

Davidson’s death was briefly mentioned on page 7 of CHESS, 14 September 1937:

In fact, Davidson survived the mauling for two days, and the circumstances of his death, in hospital, appear quite complex. Of course, that is too dull for a book such as The Even More Complete Chess Addict by M. Fox and R. James (London, 1993), and so page 22 had some ‘fun’ by making out that the lion devoured Davidson.

(5592)

For insouciant story-telling purposes there exists an ideal anecdote: the oft-related one about how Emanuel Lasker, unrecognized, intentionally lost one or more handicap games to N.N. but then turned the tables, thereby convincing his opponent that giving odds is an advantage. The setting and dialogue can be whatever the story-teller wants, in the interests of A Fun Read.

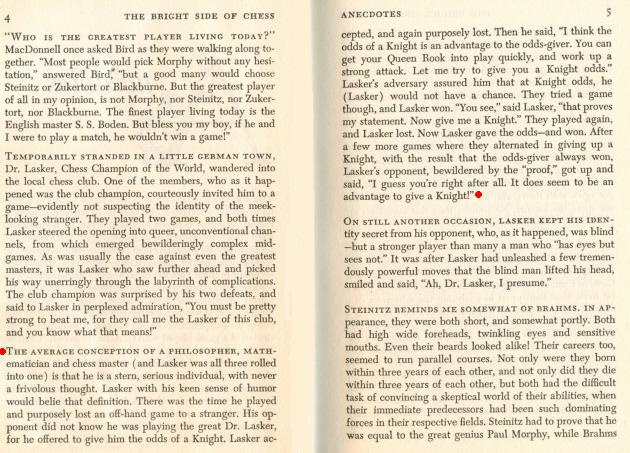

The yarn appeared on, for instance, pages 200-201 of Total Chess by David Spanier (London, 1984), but we are particularly intrigued by the wording on pages 4-5 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

As Alan Slomson pointed out on page 145 of the 30 December 1969 CHESS, the following contribution by Antony Guest appeared on page 111 of The Chess Bouquet by F.R. Gittins (London, 1897):

Alan Slomson commented:

‘Guest says this happened “some 14 years ago”, when Lasker would have been only 15 years old.’

The similarity of the wording in the Chernev and Guest texts prompts a basic question: when was Lasker’s name first introduced into the story?

(7057)

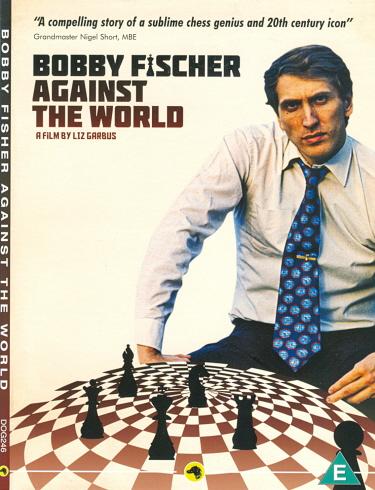

Graced with some exceptionally rich archive material, Liz Garbus’s 2011 documentary film Bobby Fischer Against the World is disgraced with some exceptionally poor interviewees. A particular low point, with some of the talking heads less concerned about being truthful than noticed, is the dense sequence which seizes on the issue of insanity:

Anthony Saidy: ‘Victor Korchnoi claimed to have played a match with a dead man and he even provided the moves.’

Asa Hoffmann: ‘Rubinstein jumped out of the window because the fly was after him.’

Anthony Saidy: ‘Steinitz in late life thought he was playing chess by wireless with God Almighty – and had the better of God Almighty.’

Asa Hoffmann: ‘Carlos Torre took all his clothes off on a bus.’

To highlight only the Steinitz versus God yarn, no scrap of serious substantiation is available. Once again we witness the magnetic pull of malignant anecdotitis. And since the theme is insanity, an uncomfortable question arises: can such groundless public denigration of Steinitz and others be considered the conduct of a rational human being?

(7345)

The reversed image of Fischer above is discussed in C.N. 12018.

Things That Matter by Charles Krauthammer (New York, 2013) has three brief chess articles, on pages 55-57, 102-104 and 108-111, but the only thing that apparently matters to him about the great masters of the past is using their lives as fodder for ‘fun’.

Page 104 (in an article reproduced from Time, 19 November 1990) has this remark, with the almost mandatory ‘once’:

‘The great Steinitz, who once claimed to have played against God and won (he neglected to leave a record of the game), went quite mad.’

There is nothing else about Steinitz, and the short paragraph moves on seamlessly to three or four lines about Fischer (dental fillings and the KGB).

(8461)

Extracts from ‘Reflections after Reykjavik’ by Gerald Abrahams on pages 84-90 of Encounter, March 1973 were given in C.N. 10497. In addition, page 89 of the article had stories about Rubinstein (who ‘was under the impression that a fly was crawling across his scalp’), Torre (who ‘decided to take his clothes off in the streets of Buenos Aires’), Steinitz (who ‘used to claim to be mad – long before his chess powers diminished’) and Morphy (who ‘retired to nursing home in Boston where he spent the rest of his life’).

C.N. 711 reported that after we complained to a columnist, James Pratt (Odiham, England), that he had published assertions about Torre taking his clothes off in a bus, Weaver W. Adams being addicted to bicarbonate of soda and Steinitz claiming that he could offer pawn odds to God, we received this reply, in a letter dated 8 February 1984:

‘You are probably correct that my anecdotes about Steinitz, Torre and Adams are untrue but I was writing purely to amuse myself. I would be very stupid if I spent hours and hours on an article, weeks on research before that, only to have it dismissed as 25% of my stuff is.’

See too pages 266-267 of Chess Explorations, which furthermore noted:

‘It makes a good story’ was also the reply received from Fred Wilson after we complained that he had published inaccuracies regarding Staunton’s background.

Another specimen is ‘you must admit it makes a good story’, a remark made to us by Larry Evans.

Illustrated Police News, 9 January 1897, page 7

Evening Express, 18 July 1922, page 4

Liverpool Echo, 22 September 1942, page 4

(12124)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.