Edward Winter

White to move. See C.N. 124 below.

The origins of the word ‘gambit’ have often been discussed in chess literature, and on page 813 of A History of Chess (Oxford, 1913) H.J.R. Murray wrote:

‘Another result of this visit [to Rome] was that [Ruy López] learnt a slang (originally a wrestling) term of the Italian players, and was afterwards instrumental in giving the word an international currency. This is the word gambit, of which López tells us in his chess work (108 a):

“It is derived from the Italian gamba, a leg, and gambitare means to set traps, from which a gambit game means a game of traps and snares, and it is used to describe this Opening because of all the Openings which Damiano gave, this is the most brilliant and trappy.”’

See also the entries on gambetto and gomito in the Dizionario enciclopedico degli scacchi by A. Chicco and G. Porreca (Milan, 1971).

Non-authorities have given other derivations for the word gambit, such as:

When did the English word gambit first appear in a chess-related text? The Oxford English Dictionary quotes the title page of the Biochimo/Beale book The Royall Game of Chesse-Play (London, 1656), which included the words ‘Illuſtrated with almoſt an hundred Gambetts’. For a photograph of that title page, see page 32 of David DeLucia’s Chess Library. A Few Old Friends (Darien, 2003).

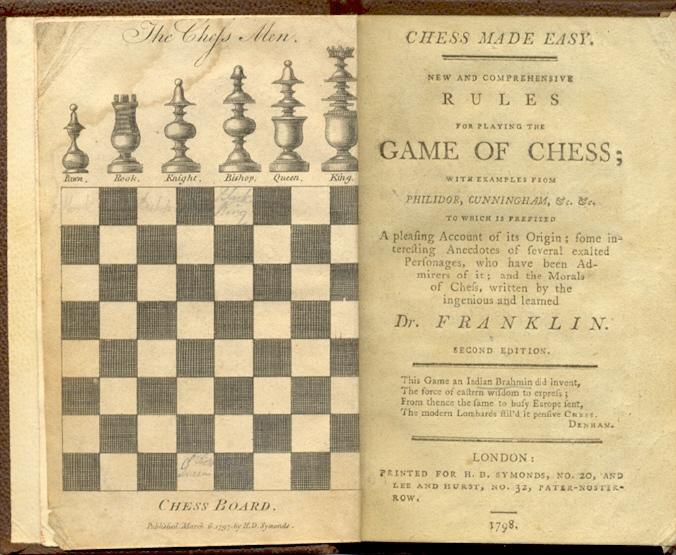

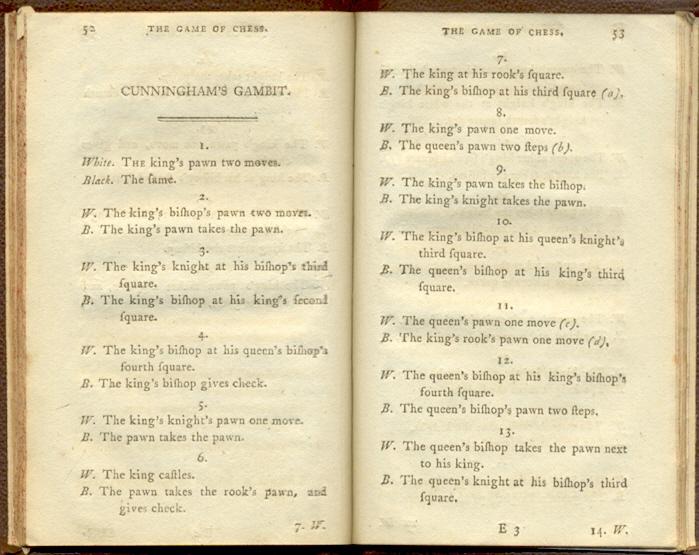

Surprisingly, the earliest instance of the modern English spelling of gambit cited by the Oxford English Dictionary dates from 1847 (C. Kenny). However, the first eighteenth-century book we checked (dated 1798, see below) had many instances of ‘gambit’:

(4592)

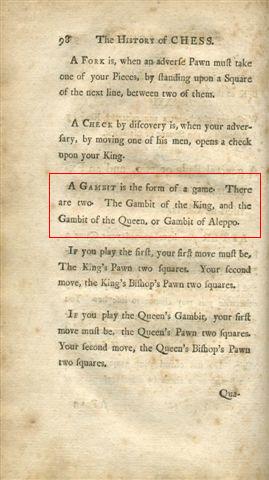

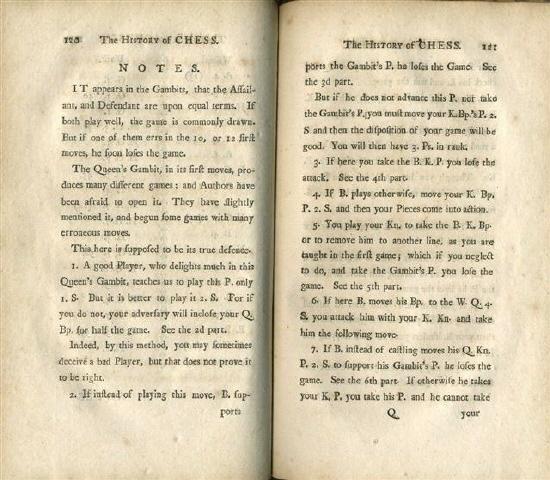

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) mentions that the word ‘gambit’ appeared regularly in The History of Chess by R. Lambe (London, 1764):

Our correspondent points out that the book is also relevant to the discussion of old works in English which adopted the algebraic notation (see C.N. 4589):

(4602)

Although W.E. Napier (1881-1952) was a highly quotable writer, he produced only one chess work, Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (published in three ‘units’, the first two in 1934 and the third the following year). After his death they were adapted into a single volume entitled Paul Morphy and The Golden Age of Chess (New York, 1957 and 1971).

From the first unit:

3. ‘In the laboratory, the gambits all test unfavourably, but the old rule wears well, that all gambits are sound over the board.’

In late 1993 Caissa Editions published St Petersburg 1914 International Chess Tournament by Siegbert Tarrasch, translated by Robert Maxham. Tarrasch’s excellent annotations have been supplemented with the notes of Georg Marco and much material from other sources.

... An example of Tarrasch’s colourful prose is his explanation on page 177 as to why, against Alekhine, he played 3 e3 after 1 d4 d5 2 c4 e5:

‘On principle, I accept no gambit as the first player, for if I must defend myself as the second player and should also defend myself as the first player, when should I then really enjoy the pleasure of attack?’

(2018)

Page 446 of The Game of Chess by Edward Lasker (Garden City, 1972) referred to ‘a remark which the great German master Siegbert Tarrasch made some threescore years ago’:

‘To win a pawn in the opening is usually a dangerous thing.’

What more is known about that observation?

(7762)

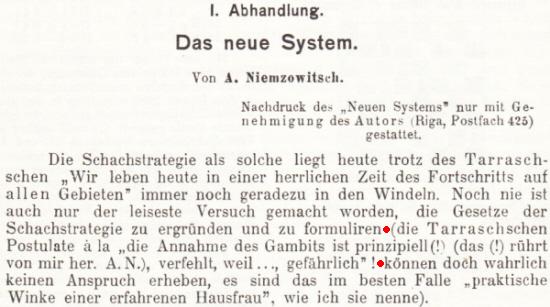

Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark) notes that on page 294 of the October-November 1913 Wiener Schachzeitung Nimzowitsch attributed to Tarrasch the following observation:

‘Die Annahme des Gambits ist prinzipiell verfehlt, weil gefährlich.’

(7770)

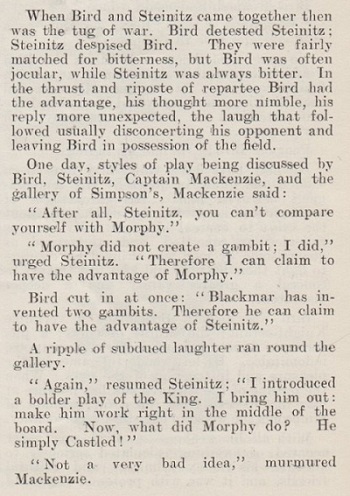

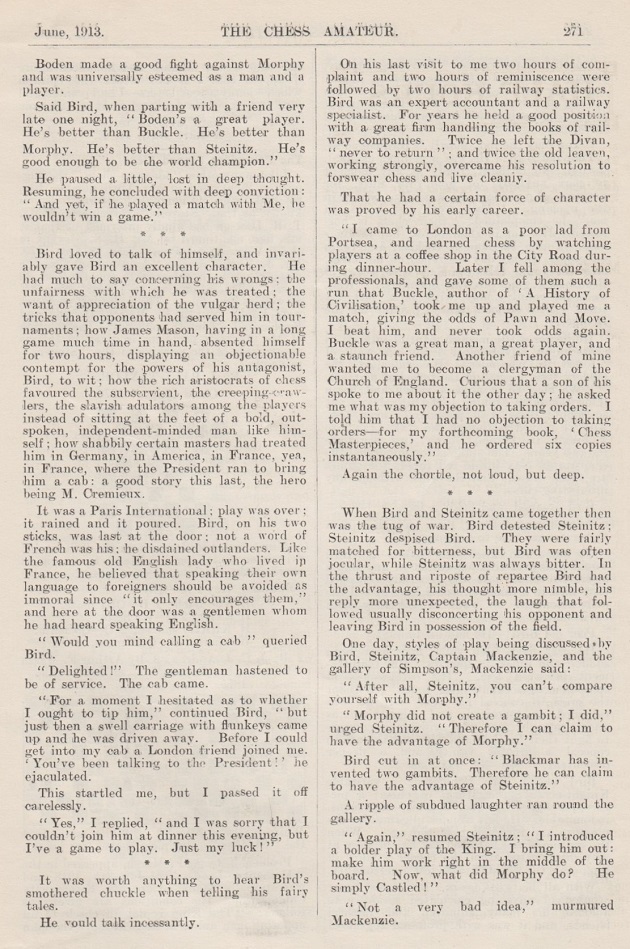

An excerpt from C.N. 9084 quoted Robert J. Buckley in the

Chess Amateur, June 1913, pages 270-272, including the

following:

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) asks what grounds Bird had for stating that ‘Blackmar has invented two gambits’ (C.N. 9084). Readers’ suggestions are invited as to the second gambit.

The full article in question is shown below, from the Chess Amateur, June 1913, pages 270-272 (‘Memories of the Masters. H.E. Bird’ by Robert J. Buckley). The Blackmar comment is near the bottom of page 271.

(9299)

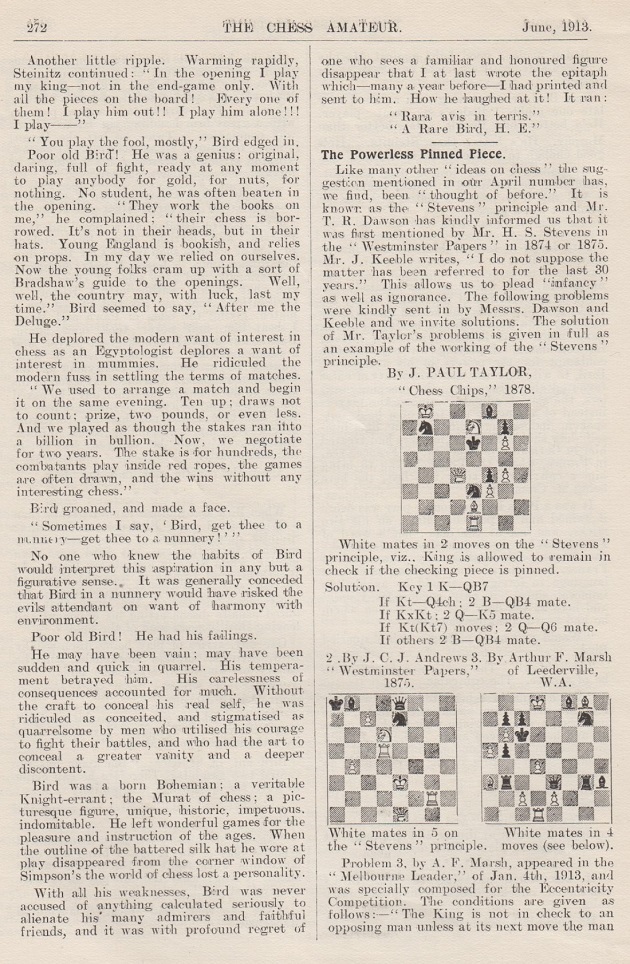

Rick Kennedy (Columbus, OH, USA) refers to pages 84-89 of The American Supplement to Cook’s “Synopsis” edited by J.W. Miller (London, 1885), which had analysis of two gambits attributed to Blackmar: 1 d4 d5 2 e4 dxe4 3 f3 and 1 d4 f5 2 e4 fxe4 3 f3. From page 84:

(9306)

C.J.S. Purdy wrote the following at the start of an article about the Evans Gambit, ‘“Evans” in World Title Tourney’, on pages 90-91 of Chess World, 1 April 1950:

‘An Evans Gambit – even if declined and if the game itself is nothing wonderful – is always “news”. This is not only because of its romantic story but because it still stands as one of the few unrefuted genuine gambits.

(9322)

A common example of the plumping process discussed in C.N. 9887 concerns quotations. When plumpers say what a given master ‘once said’, ‘often said’ or ‘used to say’, they are simply opting for one version of what earlier plumpers said was said. No caveats are expressed, and random possibilities are presented as fact.

A dictum usually ascribed to Steinitz is that the best way to refute an offer is to accept it. The wording varies, au gré du preneur, and either ‘gambit’ or ‘sacrifice’ may be plumped for.

The investigator hoping that a McFarland book will resolve the question may turn to William Steinitz, Chess Champion by Kurt Landsberger (Jefferson, 1993), but it fell far short of that publisher’s usual standards. Page 282 attributed this remark to Steinitz:

‘“The refutation of a sacrifice fervently consists in its acceptance” (80).’

The word ‘fervently’ is peculiar, but the matter can be pursued because the ‘(80)’ relates to a source note on page 473. Any hope of a precise reference to, perhaps, one of Steinitz’s books or columns, or to the International Chess Magazine, is dashed. Note 80 merely states:

‘80. Levy & Reuben. The Chess Scene. London: Faber & Faber, 1974.’

So the next step, however unpromising, is to turn to The Chess Scene, which has the following on page 70:

‘The refutation of a sacrifice frequently consists in its acceptance. Steinitz.’

As feared, we are no further forward, except that ‘fervently’ can be seen as Landsberger’s mistranscription of ‘frequently’.

Although they did not bother to say so, the exact wording given by Levy and Reuben was in the entry for Epigrams on page 119 of The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks (London, 1970):

‘The refutation of a sacrifice frequently consists in its acceptance. W Steinitz.’

Again, no source was supplied.

A few years earlier, the ‘gambit’ version had cropped up twice in book two of The Middle Game by Max Euwe and Haije Kramer (London, 1965):

‘Steinitz would certainly have taken it [a pawn], following his own motto “The only way to refute a gambit is to accept it”.’ (Page 276).

‘“The only way to refute a gambit”, said Steinitz, “is to accept it”.’ (Page 329).

Books co-authored by Savielly Tartakower and Julius du Mont had both the ‘sacrifice’ and the ‘gambit’ versions, with Steinitz mentioned in connection with the former:

‘Steinitz’s dictum that “a sacrifice is best refuted by its acceptance” is here put to the test.’

Source: page 233 of 500 Master Games of Chess, book one (London, 1952).

‘On the principle that the best refutation of a gambit is to accept it.’

Source: page 16 of 100 Master Games of Modern Chess (London, 1954).

From the previous decade, page 178 of The World’s a Chessboard by Reuben Fine (Philadelphia, 1948) had this:

‘Steinitz used to say that the way to refute a gambit is to accept it.’

Fine’s text had originally appeared on page 24 of the Chess Review, June-July 1946. On page 43 of the November 1946 issue I.A. Horowitz wrote after 1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4:

‘As a rule, and this is no exception, the best way to meet a gambit is to accept it ...’

Larry Evans’ books and articles often referred to the remark sourcelessly, and page 86 of The Italian Gambit by Jude Acers and George S. Laven (Victoria, 2003) even attributed it to him, also sourcelessly:

‘The best way to refute a gambit is to accept it. – GM L. Evans.’

From pages 221-222 of The Human Side of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1952), in his notes to an 1860 game won by Anderssen with the Evans Gambit:

‘To decline a gambit in those days was almost as unthinkable as for a gentleman to decline to fight a duel. Offering the gambit was a challenge that one could refuse only at the risk of stamping himself as a sissy and a coward.

Later on Steinitz, with the attitude of “a pawn’s a pawn for a’ that”, gave the quietus to aristocratic chess.’

That brings to mind a paragraph on page 4 of Winning with Chess Psychology by Pal Benko and Burt Hochberg (New York, 1991):

‘Steinitz believed that the choice of a plan or move must be based not on a single-minded desire for checkmate but on the objective characteristics of the position. One was not being a sissy to decline a sacrifice, he declared, if concrete analysis showed that accepting it would be dangerous. There was no shame in taking the trouble to win a pawn. A superior endgame was no less legitimate a goal of an opening or middlegame plan than was the possibility of a mating attack.’

The penultimate sentence will take us on to a related remark regularly ascribed to Steinitz. One example comes from page 228 of The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played by Irving Chernev (New York, 1965):

‘... as Steinitz once mentioned, “A pawn ahead is worth a little trouble”.’

The observation ‘When in doubt, take a pawn. A pawn is worth a little trouble’ is on page 282 of Landsberger’s above-mentioned book on Steinitz. Again, the reference is ‘(80)’, and again the quote is on page 70 of Levy and Reuben’s The Chess Scene, again without a source.

And so it goes on. Many chess writers do not take even a little trouble and, above all, they pretend to possess knowledge which they do not have. Entire websites are ‘devoted’ to sourceless quotations, that most facile way of filling space, and they are a plumper’s charter.

Assistance from readers in tracking down the exact origins of the gambit and sacrifice remarks will be greatly appreciated.

(9929)

‘And the best way to refute a gambit is to accept it.’

That observation occurs in The Pawn Gambit on page 158 of Send for the Saint by Leslie Charteris (London, 1977):

In a description of an Evans Gambit game the previous page had references to ‘the Göttingen manuscript of 1490’, ‘Bird, Blackman, Staunton, Anderssen’ and ‘Morphy, Steinity’.

The Pawn Gambit (the title The Pawn Gamble can also be found) was not written by Charteris. The contents page of Send for the Saint specified ‘Original Teleplay by Donald James’ and ‘Adapted by Peter Bloxsom’. The corresponding television episode, starring Roger Moore as Simon Templar, was ‘The Organisation Man’ (1968).

(9952)

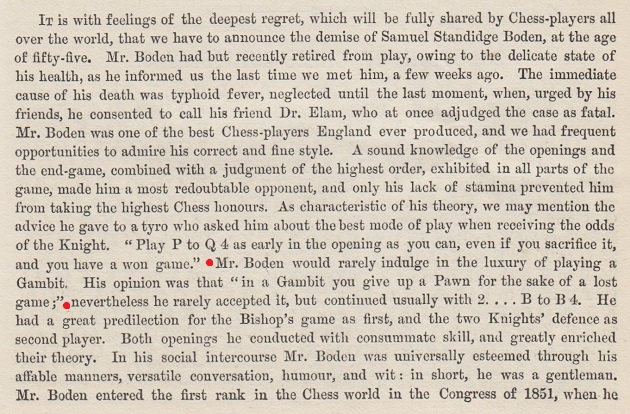

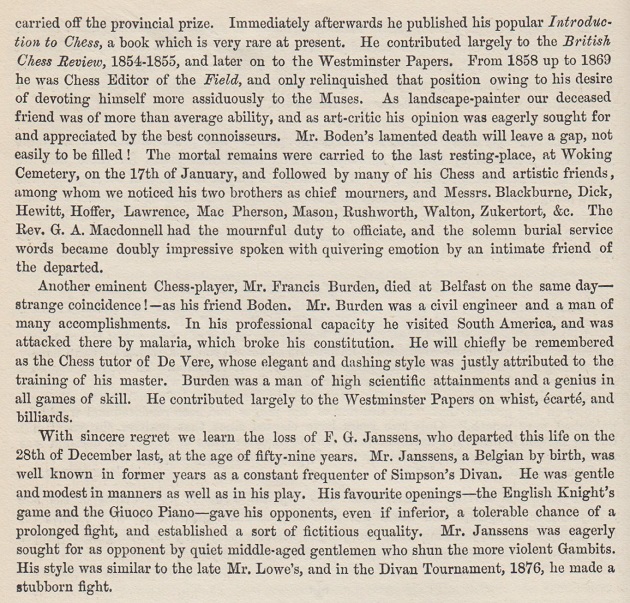

C.N. 10087, concerning A Popular Introduction to the Study and Practice of Chess by S.S. Boden (London, 1851), did not have the most famous quotation ascribed to him (about gambits giving a lost game), because there is no such remark in that volume. However, Boden’s obituary on pages 167-168 of the February 1882 Chess Monthly is noteworthy:

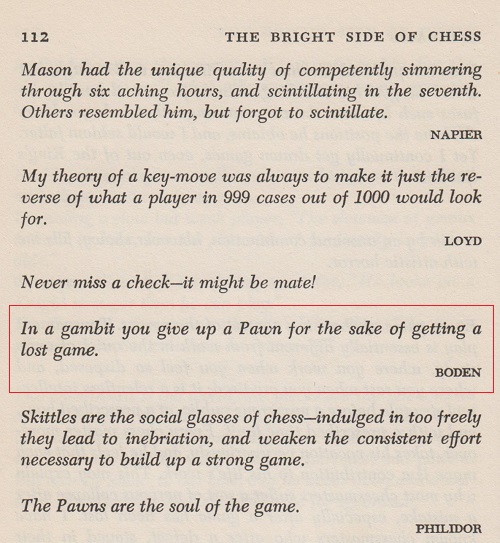

The most common wording of the dictum found nowadays is that given by Irving Chernev on page 112 of The Bright Side of Chess (Philadelphia, 1948):

This extract also offers an answer to a matter raised in C.N. 9377: why the name Boden was given in connection with the ‘Never miss a check’ comment on page 37 of Impact of Genius by R.E. Fauber (Seattle, 1992). It appears to be yet another example of the confusion caused by the lay-out of epigrams in Chernev’s book. See, for instance, C.N. 3741 and, more generally, Chess: the Need for Sources.

(10088)

Regarding the Chernev book, see also Muddled Chess Epigrams.

From the inside front cover of Chess Review, January 1954, in ‘Chernev’s Chess Corner’:

What is known about any such remark?

(11204)

C.J.S. Purdy on page 184 of Chess World, 1 August 1949:

‘Capablanca was the gambit-killer of all time.’

(11454)

A game contributed by Jeroen van de Weijer in C.N. 124:

Hugh Edward Myers – Tirso Alvarez

Santo Domingo, 24 December 1966

Amar Opening/Paris Opening

1 Nh3 d5 2 g3 e5 3 f4 Bxh3 4 Bxh3 exf4 5 O-O fxg3 6 e4 gxh2+ 7 Kh1 dxe4 8 Nc3 Nf6 9 d3 exd3 10 Bg5 dxc2 (‘And yet another one. I claim a world record for most pawns gambitted in the first ten moves: six.’ – Hugh Myers on page 26 of Exploring the Chess Openings (Davenport, 1978).

11 Qf3 Be7 12 Qxb7 Nbd7 13 Bxd7+ Nxd7 14 Bxe7 Kxe7 15 Nd5+ Kf8 16 Nxc7 Nc5 17 Ne6+ Nxe6 18 Qxf7 mate.

The Oxford English Dictionary has no entry for ‘gambit’ as a verb or for ‘gambiteer’. Regarding the latter, we note an early occurrence on page 8 of the Dublin Saturday Herald, 25 March 1899 (chess column by Porterfield Rynd):

‘Another new development is chess at the Catholic University Professor M’Neill, one of our most cultured gambiteers, seems to have infused the spirit of chess chivalry amongst the talented students of St Stephen’s green with such success that already a host of strong young players has been created quite capable of holding their own with some of our long-established junior clubs.’

From page 3 of CHESS, 14 September 1937:

(7136)

See Chess Corn Corner.

See also:

The King’s Gambit

The Meran Variation of the Queen’s Gambit

Lisitsin’s Gambit

Wing Gambits in Chess

The Evans Gambit

The Marshall Gambit

Professor Isaac Rice and the Rice Gambit

‘The Swiss Gambit’

The Budapest Defence.

Regarding other named gambits, see the Factfinder.

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.