Edward Winter

Steinitz writing on page 22 of the January 1887 International Chess Magazine (part of the justification provided for his Personal and General column):

‘... to make it disagreeable for dishonest parties who are, I believe, even less numerous proportionately in the chess world than in other walks of life, but more crafty, cunning or “smart” as it is called. Chess must be established as a thoroughly straightforward and honest game first of all before it can be made a real gentlemanly one, and unscrupulous trickery, deception and fraud must be “warned off the track”. But it requires a strong arm to accomplish that, and war on dishonest chessists cannot be made with rose water ...’

So often one reads that Ruy López suggested setting up the board so that the light shines in the opponent’s eyes. As noted on page 94 of Chernev’s Wonders and Curiosities ..., Lucena gave identical advice. Wanted: more particulars.

(906)

Ken Whyld (Caistor, England) sends a transcript of Lucena’s exact words:

‘Si jugaredes de noche con una sola candela hazed si puderedes que este siempre aman ysquierda por que no turba tanto la vista; si jugaredes de dia que agays astentar al otro en derecho de la luz que es una grande vantaja.’

(944)

From New in Chess, issue 1, page 11 (September 1984):

‘The rule that a player must move his king as punishment after an illegal continuation was taken from the book after the San Sebastián tournament in 1911, when Rubinstein gave the sealed move Kc2-c7 at adjournment in order to peacefully study at home which king move he would choose in the remaining pawn endgame.’

‘Taken from the book’ is meant in the sense of ‘removed’. Soltis’s Lists book (page 41) gives the same story – ‘perhaps apocryphal’. Is it?

(903)

Paul Timson (Whalley, England) writes:

‘I would think the story is almost certainly apocryphal. None of Rubinstein’s games at San Sebastián, 1911 fits the description given. I would also ask whether the rule referred to ever applied to sealed moves anyway. Just possibly the story derived from another incident involving Rubinstein and the sealed move. This was the game Rubinstein-Takács from Budapest, 1926. Rubinstein sealed 39 R-N7, and Kmoch describes the incident as follows:

“This move was handed up by Rubinstein just before the evening intermission. At the resumption of play, a minor incident occurred. Rubinstein came in a few minutes late. Meanwhile the tourney officials had opened the envelope and had made the move R-N2. Rubinstein immediately demonstrated that he had intended R-N7 as his sealed move. After repeated demonstration it became clear that Rubinstein had indicated the text.”’

In passing it may be noted that in the (1922) London Rules it was specified that matches would be played under the British Chess Code with a number of modifications, one of which was: ‘No king penalty for false move, except for the written adjourned move.’

Mr Timson’s analysis above is no doubt correct, but it seems a pity; should writers be deprived of their pleasure of calling Rubinstein a cheat (or Steinitz a madman ... or Alekhine an immoral sadist ...) just because of a want of evidence?

(956)

Mike Forster (Horsham, England) reverts to the topic of penalty moves, mentioning the well-known story about an endgame in which Rubinstein allegedly sealed an intentionally incorrect move, Kc2-c7.

Here we add pages 242-243 of Goldene Schachzeiten by Milan Vidmar (Berlin, 1961). It will be noted that, despite the length of the passage, Vidmar could not give particulars.

On page 502 of the September 1976 Chess Life & Review Tim Krabbé referred to Vidmar’s account, and his next paragraph turned to Breyer v Esser, Budapest, 1917, with a suggestion that White craftily touched his unmovable queen’s rook so as to be ‘forced’ to play a brilliant king move (14 Kf1). However, that was all related by Krabbé merely on a ‘the story has it that ...’ basis.

(8293)

Hugh Myers (Davenport, IA, USA) has been reading American Chess Masters from Morphy to Fischer by Arthur Bisguier and Andrew Soltis (Macmillan, 1974):

‘On pages 88-89 there is something that is too typical of master annotation. About the game Marshall-Atkins, Cable Match 1903, the co-authors say after move 24: “Black (Atkins) had played very effectively in the opening and held a considerable advantage ... White’s premature attack is repulsed.” Then Marshall played “25 P-N3!!” – “an ingenious attempt at swindle'. Marshall went on to win. They point out that annotators Mieses and Pachman didn’t understand the position, but that Marshall wrote how the game might have been drawn by the best response. So if Black had at best only a hard-to-find (and not certain) draw, why was White’s attack “premature”? And why did Atkins lose (or have only a possible draw with difficult play) if he “held a considerable advantage”??’

(997)

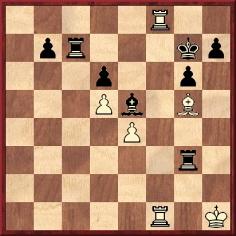

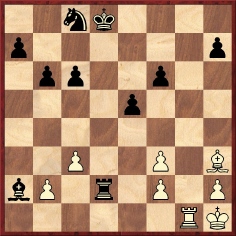

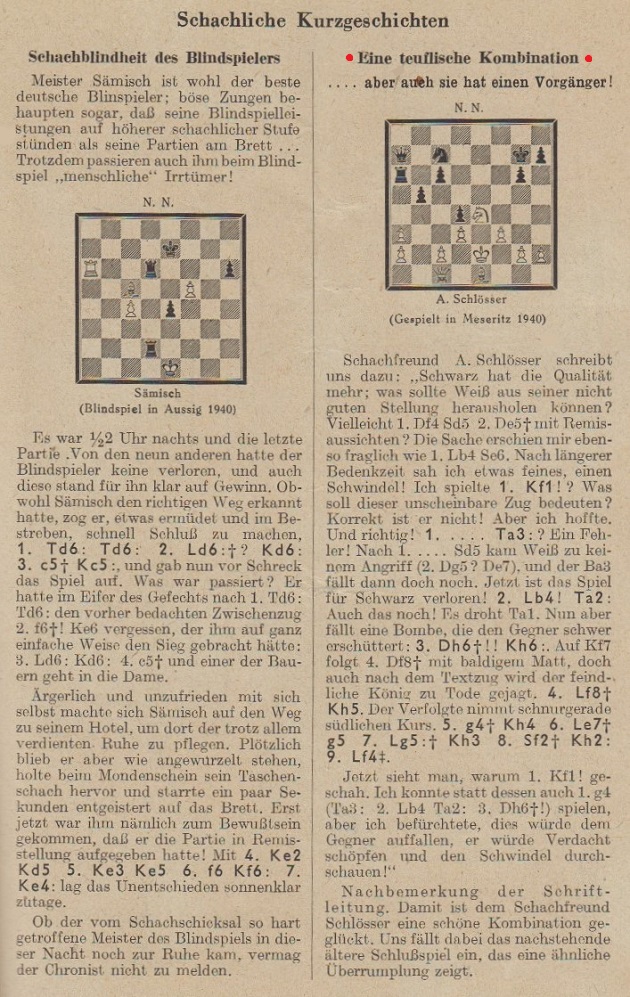

A position (Black to move) which is a good example of the Marshall Swindle and the knight fork:

F.J. Marshall v R. Swiderski, Monte Carlo, 16 February 1904

The preceding moves were 28 Rd1 Rxd1+ 29 Qxd1. Black now played the combination 29…Qxg2+ 30 Kxg2 Ne3+ 31 Kf3 Nxd1 32 c4 and White won.

Source: La Stratégie, 19 May 1904, pages 131-132. Janowsky wrote of 29…Qxg2+, ‘One of the many aberrations which occurred in this tournament; 29…h6 would have given him at least a draw’.

For some reason Kurt Richter’s Kombinationen and Irving Chernev’s Combinations The Heart of Chess mistakenly gave the occasion as Nuremberg, 1906.

(2230)

Chris Depasquale (Melbourne, Australia) points out that in the Marshall v Swiderski game Janowsky’s recommendation 29…h6 fails to 30 Qd8+ Kh7 31 Qd3+ and 32 Qxc4.

(2260)

A quote from page 102 of J. Platz’s Chess Memoirs, concerning the two Laskers:

‘... I personally witnessed when Edward came to Emanuel just to “show” him an interesting endgame position. And everybody who knew Emanuel Lasker knows that he would never ask: “Who is White and who is Black?” but go right down to the analysis of the position and get deeply involved with it. And that is how Dr Edward Lasker got a thorough analysis of a position which in reality was one of his adjourned tournament games! Emanuel Lasker never knew the truth.’

From pages 30-31 of Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood by Edward Lasker:

‘Some contestants think nothing of showing adjourned positions to stronger players and asking their advice. In fact, they have grown so accustomed to this unfair practice they are almost no longer capable of realizing that what they do is just plain cheating, whether sanctioned by usage or not.’

(747 & 811)

From G.H. Diggle (Hove, England):

‘There have been innumerable chess piracies and plagiarisms, but few actual “frauds”, though there was once an attempted “impersonation” of a chess master. On page 363 of the November 1855 Chess Player’s Chronicle Brien (then the Editor) writes:

“During the Michaelmas week an impostor appeared in Huddersfield under the name of Mr Zytogorski, who had not left London for a long time. A similar fraud was perpetuated, we hear, at Leamington and in other parts of Yorkshire. Our country readers cannot be too much on their guard against such an imposture.”’

(1875)

An Endnote on page 264 of Chess Explorations:

In C.N. 1861 Bob Meadley wrote a seven-page account of ‘The Great Chess Fraud of 1870’, concerning Andrew Burns and Alexander McCombe in Australia. A Blumenfeld/Przepiórka imposture was related in C.N. 2007.

Two players often alleged to have invented brilliant wins are V. Tietz (see C.N.s 215, 321, 516 and 896) and Prince Dadian of Mingrelia (C.N.s 1334, 1490, 1503, 1542 and 1627).

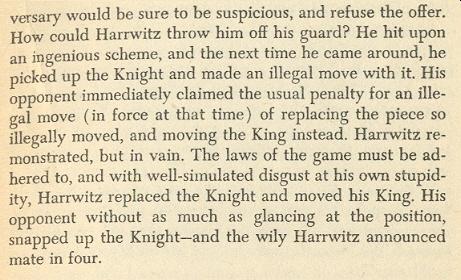

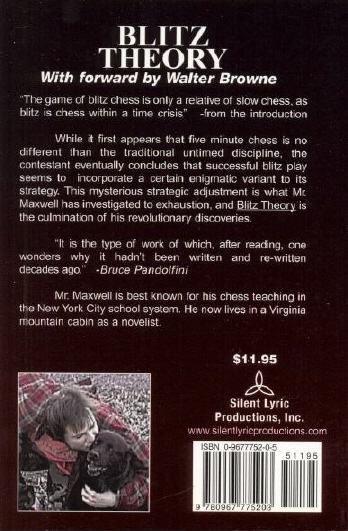

Below is a position (‘The “Swindle” Triumphant’) from page 44 of the Chess Weekly, 11 July 1908. ‘This pretty stratagem occurred last week in a game at the Brooklyn C.C.’ between Charles Curt (White) and Magnús Smith:

Black to play

The game went: 1…Kg7 2 Bc2 Kg6 3 Bd1 Kg5 4 Rxg3+ Qxg3 5 f4+ Kg6 6 Qh5+ Rxh5 7 Bxh5+ Kxh5 8 Bxg3 Kg4 9 Kg2

9…c5 (‘This loses at once. The ending, however, seems to be lost, play as Black may. For example, 9…Kh5 10 Kh3 Kg6 11 Be1 Kf7 12 Bb4 Kg6 13 Kh4 Kh6 14 Be7 Kg6 15 Bg5 Kh7 16 Kh5 Kg7 17 Be7 Kh7 18 Bf6 Kg8 19 Kg6 Kf8 20 Bh4 Ke8 21 Kf6 Kd7 22 Kf7 c5 23 dxc5 Kc6 24 Ke8 Bd7+ 25 Kd8, etc., which deserves a place in the books of end-play.’) 10 dxc5 d4 11 a6 and wins.

(2714)

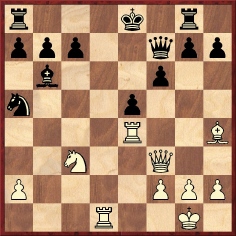

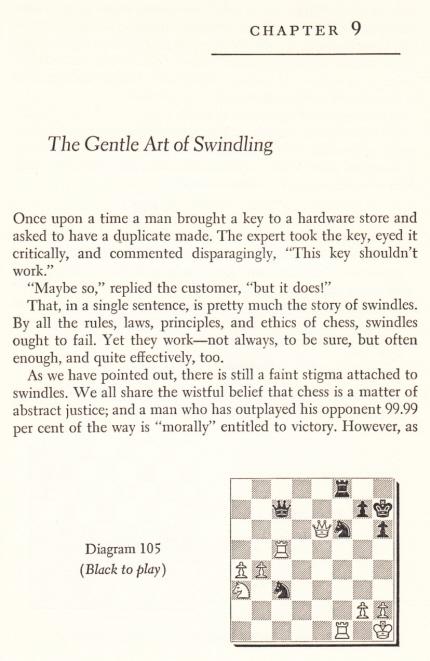

C.N. 2761 quoted from pages 164-165 of Complete Chess Strategy: Play on the Wings (London, 1978 and New York, 1979), where Ludĕk Pachman related a piece of foxiness to which he resorted in his game against Zbigniew Doda of Poland at the Capablanca Memorial Tournament in Havana, 1965:

Doda (Black) has just played his knight to e5 from d7, threatening to bring it to either g4 or d3. Pachman relates:

‘My first reaction was to consider immediate resignation at this point, but I then saw the glimmer of a chance. If I could ward off the immediate threat with Qd2 and after …Nd3 guard the b-pawn by Nd1, leaving the f-pawn en prise, instead of playing the obvious but passive Nce2, then it would be dangerous for Black to capture the f-pawn in view of the sudden resurgence of White’s attack by Nf5! However, it seemed too slender a prospect that my opponent would readily fall in with my plan. He only had to check that it would be risky to capture the f-pawn after Nd1!? and White’s position would be hopeless in view of the strongly-placed black knight. Was there any way of “bluffing” my opponent into capturing the pawn? If I were in time-trouble he might imagine that Nd1 was a blunder on my part, but I had more than one hour for the remaining 13 moves! This meant that, in order to attempt this ploy, I would have to devote most of the remaining time to “thinking about” 28 Qd2, and then play 29 Nd1 very quickly in my artificially created time-trouble! And so I stayed quietly at the board for a whole hour, thinking of anything but chess and patiently suffering the sight of my fellow competitors gathering around the board to gaze upon the ruins of my position. I allowed myself a mere three minutes for the remaining 13 moves, the absolute minimum required in case my opponent should err. Meanwhile he was walking about on the stage, no doubt pleased with his position and returning to the board occasionally to check the time on my clock.

At three minutes to the hour I played 28 Qd2 and after 28…Nd3 the immediate 29 Nd1, whereupon Doda glanced at my clock, thought for no more than 30 seconds, then captured the pawn 29…Nxf4? (of course 29…Bg4 was one of the various ways to win). The rest of the game followed at lightning speed, with my opponent in no way short of time but clearly depressed by the piece sacrifice: 30 Nf5! gxf5 31 Rg3+ Kh8 32 Qxf4 Rb3? (even after the better 32…Qxe4 White would have a strong attack by 33 Qd2 f4 34 Rf3 and 35 Rxf4) 33 Nc3 Rxb2 34 exf5 Bd7 35 Ne4 Re2 36 Nxf6 Rxf6 (after 36…Re5 37 Ng4 Rxf5 38 Nh6! Rf8 39 Rg5! wins) 37 Qg5 Re1+ 38 Kh2 1-0.’

Pachman annotated the full game on pages 59-61 of his subsequent book Jak přelstít svého soupeře? (Pliska, 1990). An ironic point not mentioned by him in either work is that according to page 78 of the tournament book (IV Torneo internacional “José Raúl Capablanca”, published by Editorial Sopena Argentina S.A., Buenos Aires in 1965) Black lost by overstepping the time-limit.

Later on, in C.N. 2853, Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) pointed out that a slightly different version of this episode was related by Pachman on pages 85-87 of his book Ajedrez y Comunismo (Barcelona, 1974), i.e. the Spanish version of Jetzt kann ich sprechen (Düsseldorf, 1973):

‘The clock indicated that there were still two minutes until the time-limit. In fact, that was the margin that I had intended for executing the ten remaining moves. I made the move that I had thought of one hour previously. Doda quickly returned to the board and, after thinking briefly, took my pawn. With feigned alarm, I looked at the clock and, at the speed of light, I put another pawn before his nose. He shook his head, glanced at my clock and took the pawn. He certainly thought that I was lost and that, on account of Zeitnot, I had lost all control and would sacrifice one piece after another. With stunning speed, yet another sacrifice. This time Doda suspected something; he put his head in his hands and thought intensely. But it was already too late. (...) With blow after blow I was cornering the black king. Barely two minutes had sufficed to carry out the devastating attack. Shortly before the time-control, my opponent resigned.’

See also pages 56-57 of Pachman’s book Checkmate in Prague (London, 1975).

Biographical information about Zbigniew Doda is given on pages 45-53 of Polscy szachiści by Władysław Litmanowicz (Warsaw, 1976).

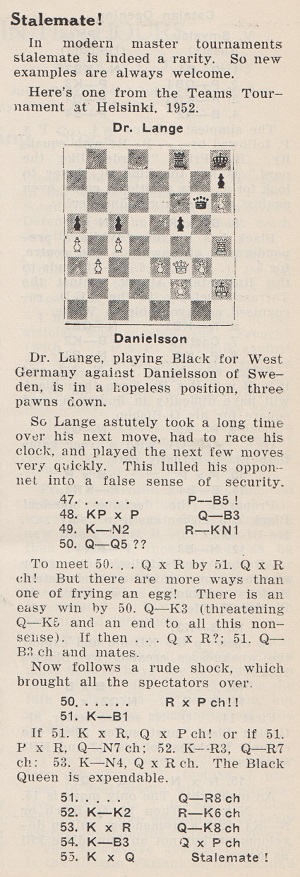

Further to C.N. 2761, Jonathan Hinton (East Horsley, England) draws attention to a similar, earlier case, reported on page 65 of Chess World, April 1953:

(10520)

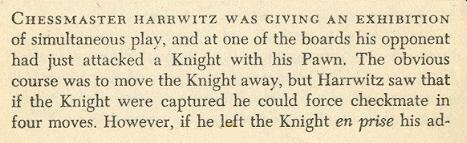

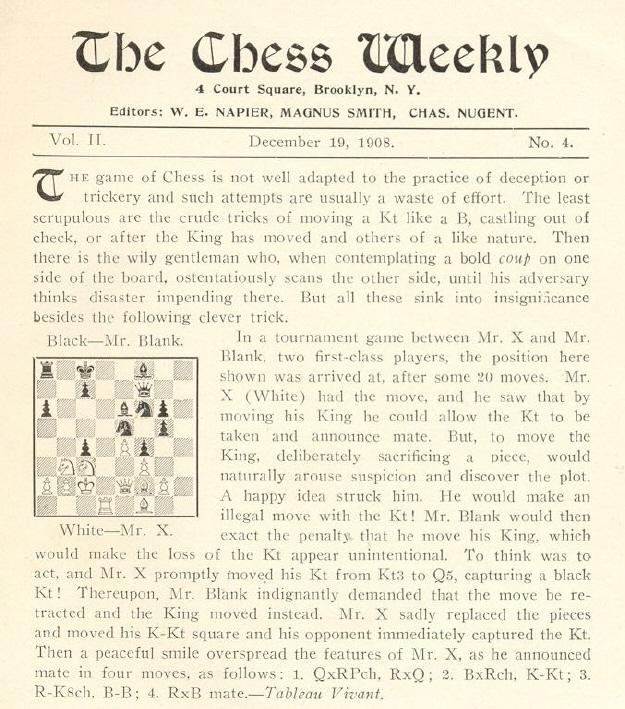

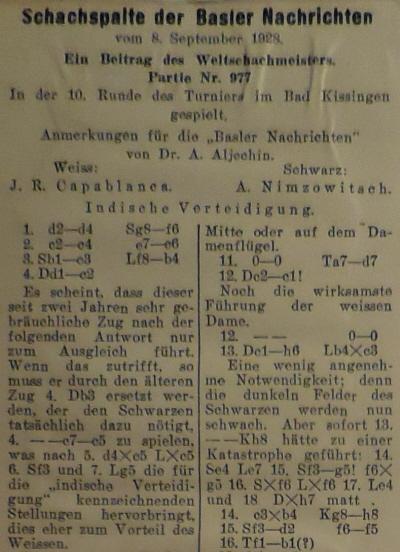

This familiar anecdote from pages 12-13 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948) was given in C.N. 4386:

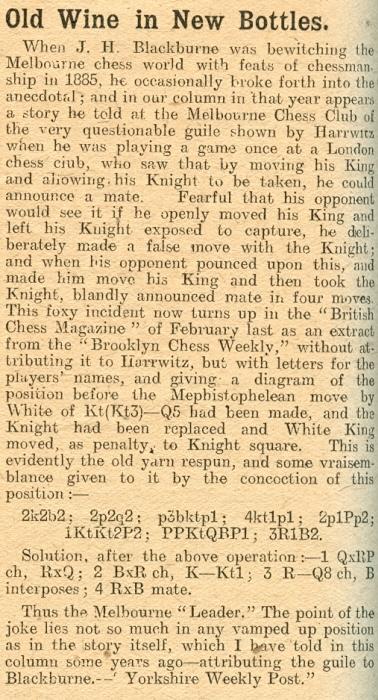

Chernev did not specify his source, but the story had appeared on page 25 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 24 June 1885 and on page 232 of the June 1885 BCM, with both magazines recording that, according to the Melbourne Leader, it had been related by Blackburne. See also page 222 of the November 1915 American Chess Bulletin. The wording is similar in all four cases.

The C.N. item mentioned that we had not come across any publication of the tale during Harrwitz’s lifetime (he died in 1884) or any further information about the position in question. On the other hand, we added that under the title ‘Skulduggery’ C.N. 2157 had given a position which had appeared in the Chess Weekly (19 December 1908, page 25):

The over-the-board play corresponds perfectly to the Harrwitz story: White made an illegal move with a knight which was under attack by a pawn and, after moving his king as a penalty and having his knight captured, he announced mate in four. Can all this be a coincidence, or does a more complicated explanation exist?

The above position was also given in C.N. 2157, based on its appearance on page 53 of the February 1909 BCM.

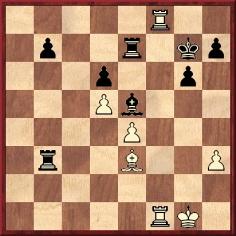

Next, a more innocent episode. Page 243 of the June 1892 BCM had the following position, which was discussed in C.N. 4450:

Jackson Whipps Showalter v Professor J.E. Logan (White to play)

W.H.K. Pollock commented:

‘And here we can save a separate chapter on “Showalter’s Chess Finessing, or High Cunning”, by giving a diagram of a game-ending which does seem to illustrate the peculiar feature called finesse – like a trap, good play, if the prey snaring himself, the trapper loseth neither bait nor tackle. This was the outcome of an Evans, played by correspondence, between Mr S. and a strong amateur of Louisville.

Now White (as the moves will shew) would like Black to play ...Nc4. Therefore he does not play Qf5 at once, but makes a move to prevent ...Nc4, in other words puts it into his opponent’s head to play ...Nc4. The game proceeded 18 Qg4 h5 19 Qf5 Nc4 20 Rxc4 Qxc4 21 Nd5 Qc5 22 Qe6+ Kf8 23 Bxf6 Re8. White announced mate in seven (24 Ne7, etc.).’

The full game-score of the game was given in C.N. 2694 (see page 199 of A Chess Omnibus), from page 382 of La Stratégie, 15 December 1890. For the record, the moves were: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Bc5 6 d4 exd4 7 O-O d6 8 cxd4 Bb6 9 Nc3 Na5 10 Bg5 f6 11 Bxg8 Rxg8 12 Bh4 Bg4 13 e5 dxe5 14 Re1 Bxf3 15 Qxf3 Qxd4 16 Re4 Qd7 17 Rd1 Qf7 18 Qg4 h5 19 Qf5 Nc4 20 Rxc4 Qxc4 21 Nd5 Qc5 22 Qe6+ Kf8 23 Bxf6 Re8. The announced mate in seven moves is 24 Ne7 Qxf2+ 25 Kh1 Qxf6 26 Ng6+ Qxg6 27 Rf1+ Bf2 28 Rxf2+ Qf6 29 Rxf6+ gxf6 30 Qxf6.

Another example was recorded in C.N. 5145. From pages 24-25 of Not Only Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1974):

‘... Cold-blooded gamesman-planning is rare. But I have one pretty example. At my first British Championship, [at Ramsgate] in 1929, a friend of mine – who is a magnificent analyst and celebrated in the chess world – found himself in a very bad position. But there was a way out. Given that his opponent (a very strong player) did not see the threat, it was possible, with a series of sacrifices, to achieve stalemate. But he had to include in his play a clearly inadequate move, which would inevitably warn his opponent. After all, one plays chess on the assumption that the opponent sees everything. (That is why the word “trap” is not a good chess term.) But my friend devised a psychological trap. He sat and looked at the board with a despairing face until he was well and truly in time trouble. Then he fumblingly made the crucial moves. His opponent, tempted to a little gamesmanship himself, was playing very quickly. Quick came the erroneous capture. Even quicker came the series of sacrifices and, while the flag was tottering, stalemate supervened. Now could he have improved on things in the following way: touched the piece, taken his hand away, and let himself be compelled to move the piece at random? No, he had thought of that, but dismissed it as sharp practice.’

Abrahams then gave the relevant position:

‘Time control at move 40. At move 31 Black has played R-Kt6, a good move, because, if either rook guards the bishop, RxB wins.’

Play continued: 32 Bd2 Rg3+ 33 Kh1 Rxh3+ 34 Kg1 Rd3 35 Bc1 (‘Leaving himself less than half a minute on his clock.’) 35...Rc7 36 Bg5 (‘Finger staying on his clock; and Black falls for it.’) 36...Rg3+ 37 Kh1

37...Rxg5 38 R1f7+ Rxf7 39 Rxf7+ (‘Forcing stalemate or perpetual check.’).

Abrahams did not name the players, but the position after White’s 37th move was given on page 346 of the September 1929 BCM. W.A. Fairhurst was White against T.H. Tylor.

A topical thought in conclusion. Unspecific accusations of dishonesty concerning chess players will result in an international news story. Specific proof of dishonesty concerning chess writers will result in international silence.

The above, which originally appeared at ChessBase.com, on 23 January 2011, incorporates a few additions and other amendments.

From Jonathan Hinton (Horsley, England):

‘I have a query concerning a strange drawing combination, which occurred in an otherwise forgettable speed game I played against Richard Francis in Crowborough in 1991:

As Black I had sacrificed my queen, but the intended 1...Nd3+ loses to 2 Kd1 Nxe5 3.b8(Q). So I tried the swindle 1...Rg1+, which should lose rapidly after 2 Kd2. But White fell for it by immediately playing 2 Nxg1, and after 2...Nd3+ 3 Kd1 Nxb2+ 4 Kc1 Nd3+ I had a draw by perpetual check (knight checks on d3 and b2), since the king cannot venture to b1 or f1 because of mate from the rook. Has this unusual drawing combination been seen in master play?’

(2564)

A national championship. Certain players collude by delaying games among each other in order to determine which of them has the best chance of unhorsing the tournament front-runner. One participant even throws a game, allowing himself to be mated on move two.

For information about this remarkable episode we are grateful to Luc Winants (Welkenraedt, Belgium), who writes as follows:

‘I would like to draw your attention to my own website, which is dedicated to the history of chess in Belgium. Concerning Koltanowski, about whom you have written recently in C.N., the account of the second Belgian Championship, held in Antwerp in September 1922, reveals some interesting details [http://users.skynet.be/jardinsdecaissa/belch/belch22.html – link no longer available]:

One chronicle, written by Edouard Verschueren, a friend of Edgard Colle, for La Flandre Libérale, 4 October 1922, states the following:

“C’est à ce moment que les joueurs anversois se sont liés contre le champion, dans l’espoir de lui ravir encore le titre. Volontairement on remettait des parties entre les joueurs anversois (Koltanowski-Dunkelblum), afin d’attendre le résultat de M. Colle et d’avantager alors le joueur ayant encore des chances; on lui cherchait toutes les difficultés possibles au jeu, tandis que, d’autre part, des parties entre Anversois finissaient dans des limites de temps ridicules, et ainsi M. Koltanowski gagnait la partie suivante contre M. Boruchowitz, ancien champion de Belgique:

1 f3 e5 2 g4 Dh4 mat. Ce n’est évidemment pas des parties pareilles qui donneront un lustre à nos joueurs anversois; le plus petit débutant aurait évité cette gaffe ... volontaire.”

Thus, as you can see, the game between Boruchowitz, the winner of the first championship in 1921, and Koltanowski finished after only two moves: 1 f3 e5 2 g4 Qh4 mate.’

Despite the plot against him Colle won the event and the national title, half a point ahead of Koltanowski.

(2928)

C.N. 3639 quoted the following passage from page 242 of Official Chess Handbook by K. Harkness (New York, 1967):

‘So far as the complaints of collusion among Soviet players are concerned, it is undoubtedly true that the Soviet contestants in FIDE tournaments, especially in the early competitions, have played as a team and not as individuals. Alexander Kotov admits this in his Memoirs of a Chessplayer, published in the USSR in 1960. He apologizes for his victories over Smyslov in 1933 [sic – 1953] and Botvinnik at Groningen in 1946, and hopes he will be forgiven, since he made up for these lapses by defeating Reshevsky and Euwe respectively in these tournaments.’

From Steve Giddins (Moscow):

‘Harkness’s reference to Kotov’s “Memoirs of a Chessplayer” presumably means the book Zapiski Shakhmatista (Moscow, 1957), a title more appropriately rendered as “Notes (or Jottings) of a Chessplayer”. I have translated into English the relevant passages concerning the Groningen, 1946 game against Botvinnik (pages 121-122) and Kotov’s win over Smyslov at Zurich, 1953 (pages 196-197). The 1960 edition of Kotov’s book was effectively just a reprint, with no material textual changes.’

Our correspondent’s translations are given below. Firstly, from pages 121-122 and Groningen, 1946:

‘When Botvinnik had established a clear lead and Euwe was trailing him, various reactionary newspapers decided to support their champion by means of the familiar propaganda: “It’s impossible to compete with the Russians”, claimed one Catholic newspaper. “One only has to look at how they have all lost intentionally to Botvinnik. Smyslov lost to him, Boleslavsky also. We know for a fact that they are all under strict orders to lose to Botvinnik without any struggle, and thereby assist him into first place!”

This unceremonious invective contained as much truth as it did logic. In the first place, Botvinnik had won both the games against his Soviet rivals only after sharp battles, subtly outplaying his opponents. Secondly, Botvinnik’s lead did not result from just two games – two points is hardly enough to put one in the lead after 13 rounds of a tournament. Botvinnik had also beaten eight other players from various countries in Europe and America. But, as is well known, invective has no need of logic!

Throughout the first 13 rounds of the tournament, this Catholic paper kept up similar commentary. However, it did not help Euwe. Although he remained hot on Botvinnik’s heels, he could not catch him.

Then came the 14th round, in which I played Botvinnik. The tournament leader played the opening badly and too riskily and, having reached an inferior position, overlooked a relatively straightforward combination and lost. The Dutch were celebrating. Botvinnik is beaten! To their surprise, a compatriot had done to Botvinnik what the Western masters had been unable to do. Now Euwe had caught up with Botvinnik. We ourselves were highly interested in one question: what would the newspaper which had been screeching about a conspiracy between the Russians say now? How would they get out of the ticklish position in which they now found themselves?

It would appear that the shameless know no bounds. On the following day, the newspaper reported my game with Botvinnik in detail, and placed it under the headline: “Russian defies Kremlin orders! Future fate of Kotov uncertain!”.

What more can one say about such filthy slander and evil-minded fantasy?’

Alexander Kotov

From pages 196-197:

‘Smyslov’s only defeat in the Zurich tournament was against the author of these lines. At that point, Smyslov was leading. I was somewhere in the middle of the tournament table. Reshevsky was right behind Smyslov. The reader will understand my situation: just as in Groningen, I had obstructed a colleague’s path to the supreme sporting title, without the win bringing any material improvement to my own tournament position. I understood very well the absurdity of what had happened, and that I would not get any plaudits for this win over Smyslov from my compatriots, who so closely shared in the successes of the Muscovite. It is sufficient to say that when, as usual, I telephoned my wife in Moscow that evening, she immediately asked me:

“What are you playing at over there? I’ve had chess fans on the phone here, cursing you. Is that what you want?”

But there was nothing to be done – sport is sport! I secretly hoped that I would be able to undo some of the damage later on. I still had one more game to play against Smyslov’s main rival, Reshevsky. And so it happened. Exploiting Reshevsky’s inaccuracies, I won. Thus, the Groningen story was repeated.’

Mr Giddins comments:

‘It is quite clear from the above that no admission of the sort that Harkness alleges is made; quite the contrary. Indeed, it is inconceivable that any such admission could have been made, given Kotov’s known Communist loyalties, and the heavy hand of the Soviet censor. I can only assume that Harkness himself did not understand Russian (a supposition supported by his mistranslation of the book’s title) and was merely reciting something he had been told by somebody else. It may be that, in some other context, Kotov joked about asking “forgiveness” for beating his colleagues, but to suggest that this amounts to an admission of a conspiracy is quite unjustified.

One point worth clarifying is that in the Smyslov section Kotov refers to having, for the second time, “obstructed a colleague’s path to the supreme chess title”. It may be wondered in what sense his defeat of Botvinnik at Groningen, 1946 could be said to have done this. The answer is that, when discussing Groningen, Kotov makes great play of the fact that, had Botvinnik not taken first place ahead of Euwe, the latter would almost certainly have been declared world champion by FIDE, without any match-tournament taking place. Kotov therefore argues that winning Groningen was an essential step for Botvinnik in securing the chance to play for the world title.’

We are grateful too to Claes Løfgren (Randers, Denmark), who has also provided translations from Kotov’s book, commenting to us, ‘I do not see any admission of foul play’. That conclusion is shared by Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina), who has submitted extracts from the Spanish translation of Kotov’s book, Apuntes de un ajedrecista (Moscow, 1959).

If the only problem with Blitz Theory by Jonathan Maxwell (Flint Hill, 2005) were the typos and shoddy language (enough to have even a Cardoza author looking over his shoulder), the book would not be mentioned here, just as most Cardoza tomes have been passed over in mute dismay. Since, however, the back-cover blurb of Mr Maxwell’s book bills it as ‘the culmination of his revolutionary discoveries’, readers may welcome an inkling of what he has revolutionarily discovered. We therefore pick two examples, the first being on pages 92-93:

‘... when [a piece] is placed with too much inaccuracy, the veteran player is greatly distracted at this “smudge” on the board. By purposely creating such smudges, we can favorably distract our opponent into serious blunders. Let’s look at an example ...

The move Nf5 creates a standard discovered attack on the queen, and will be seen in a typical situation. By placing the knight not directly in the center of the square, but a good ways past the edge of the square, there is a fine chance that the opponent’s flow of concentration will be jostled, and his view of the position will now be skewed in the direction of the “sloppy knight”. Now that he is distracted to the wrong side of the board, there is every likelihood he will miss the attack on his queen, and leave it vulnerable to the naughty bishop.’

On page 96 the revolutionary discoverer offers further counsel which is absent from Chess Fundamentals:

‘When we have an obvious check with a rook or queen, we don’t play the check, but instead say “check” while merely cutting the king by placing the piece on the line adjacent to the check. In the above diagram, our opponent will expect the move to be the Rg8 check. Instead, we say “check” while playing the wily Rg7 blitz tactic! Now there is every chance that upon seeing the typical rook thrust he will move out of the anticipated check, and walk right in to our true check. We can then claim his illegal move as our victory.

This is a perfectly legal tactic. While the unfortunate mark may complain about the validity of the swindle, the fact is that there is no such thing as a “false check call”. Vocal declarations of check have no relevance in blitz or slow chess. Only the board speaks of the king’s danger.’

The back cover sports an appreciative word from Bruce Pandolfini, and the opus has a foreword (‘forward’ three times in Mr Maxwell’s spelling) by Walter Browne. While dissociating himself from ‘the “pseudo check” technique’, Browne writes, ‘Otherwise I endorse this uniquely insightful book with open arms!’

(4311)

Students and/or practitioners of cheating at chess en famille should consult the reminiscences by Simon Gray on pages 25-28 of The Year of the Jouncer (London, 2006).

(4718)

‘... Chess is possibly the only game in the world in which it is impossible to cheat.’

So says a character in chapter 4 of Sweet Thursday by John Steinbeck (New York, 1954):

It may, though, be recalled from our feature article A Chessplaying Statesman that Sir John Simon remarked in a speech in Cambridge in March 1932:

‘... We may describe chess as the politician’s game, for obviously there are some qualities which make it particularly suitable for politicians; for example, nobody can cheat in chess. So far as I know it is the only game in the world in which it is impossible to cheat.’

(5064)

Concerning Steinbeck, see also C.N.s 9413 and 12177.

A further article by the Badmaster, G.H. Diggle, from the April 1977 Newsflash and page 21 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘W.R. Hartston’s disgraceful book How to Cheat at Chess (a work “without which no Badmaster’s bookshelf could possibly be complete”) was lapped up with avidity by the present BM while commuting from Lewes to Victoria. He had omitted to conceal from public gaze the brazenly gaudy title on the cover, and even before reaching Haywards Heath his fellow passengers were exchanging significant glances, while a ticket inspector on the train subjected the BM’s “Season” to a minute scrutiny before allowing him to resume his “nefarious perusal”. The BM, who after 50 years of chess gamesmanship flattered himself that he knew every trick of the trade, is forced to admit that on nearly every page of this comprehensive work some completely fresh specimen of low rascality held him captivated and enthralled.

There are, however, one or two “Irregular Openings” which Mr Hartston has omitted to notice, possibly because they may have become obsolete before his time. Perhaps the most diabolical tactician the BM ever encountered was in a rather rustic Minor County match. Before our game started he affected a sort of weary affability: “These awful matches, you know – they will keep roping me in – I much prefer to play chess for fun”, etc., etc. Then he picked up our chess clock with some revulsion: “Oh gosh, have we really got to use this contraption? Can’t we be naughty and discard the beastly thing?” On the BM replying, “Perhaps we had better do as Rome does”, he observed: “Well, just keep an eye on me, that’s all – I shall never remember to press the bleeding button, or worse still, I shall keep on pressing the one on the next board – I’m left-handed, you know.” Then we were handed our score-sheets: “What’s this blasted dossier? Name of opponent? White’s time? Black’s time? This is Chess Bureaucracy gone mad. Would you mind ‘keeping the Minutes’ – I’m sure you are one of those enlightened coves who understands this idiotic notation.” Reduced by these blandishments to a thoroughly fidgety state, the BM played “at least a rook below his usual strength” and when time was called Machiavelli was a pawn up, though with bishops of opposite colours. “It looks rather drawish”, ventured the BM. Then the villain showed the cloven hoof. “Pity I won that pawn! You know what these Match Captains are. It’ll have to go up to the House of Lords, I suppose – there must be a win somewhere, and no doubt some bore will plough through every blasted variation till he finds it. Isn’t it absurd?”’

(6837)

From page 308 of the July 1920 Chess Amateur:

After correction of a couple of obvious errors in the Forsyth notation the position, it will be noted, is the same as the one given on page 25 of the 19 December 1908 issue of the Chess Weekly (which did not mention Harrwitz).

(7129)

Another version of the tale, this time with Blackburne supposedly claiming that he was the player in question:

‘A good story is told by J.H. Blackburne, which runs as follows:

“When playing a game once at a London Chess Club I saw that by moving my king and allowing my opponent to capture my knight I could announce mate. Fearful that my opponent would notice this, I deliberately made a false move with the knight, and my opponent pounced upon this and made me move my king. Needless to say, my man took the knight, and I blandly announced mate in four.”’

Source: Chess Amateur, November 1921, page 36.

(7206)

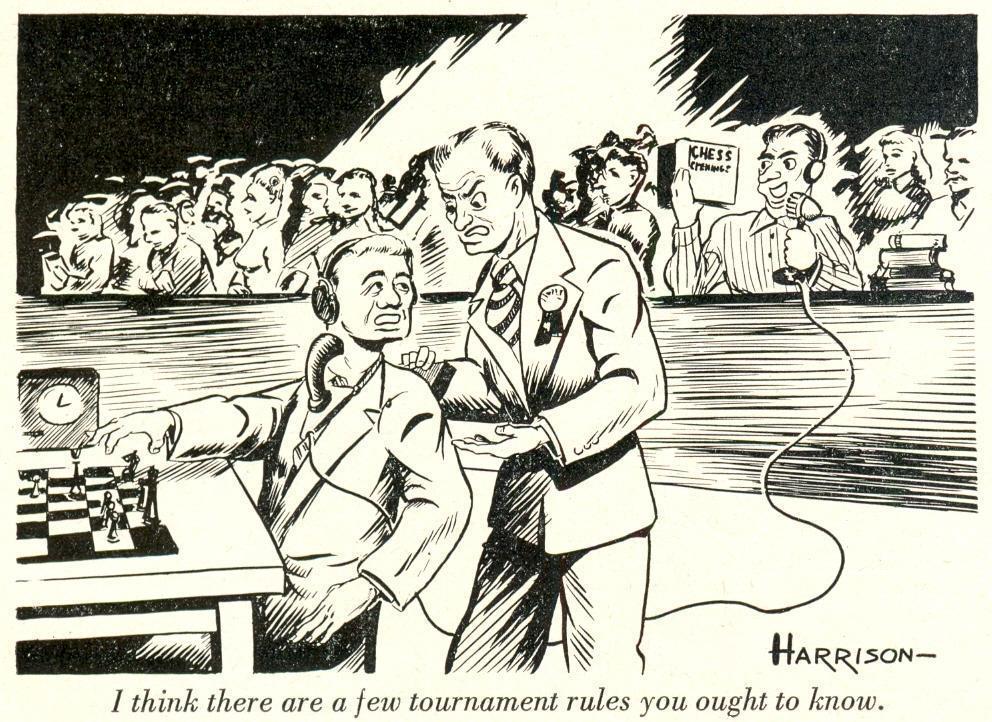

Below is the opening of a ‘Chess Explorations’ article which we contributed to ChessBase on 2 September 2011:

Recent reports of alleged cheating put us in mind of two old US cartoons. The first, by George Price, comes from page 131 of the June 1939 Chess Review:

The second cartoon, from page 24 of the March 1948 Chess Review, depicts a rather more sophisticated technique:

Information is still being sought on an alleged incident related in C.N. 1263 (see page 14 of Chess Explorations). In an article ‘Triche, triche et colégram ...’ in Le Courrier (Geneva), 11 April 1986, Fernand Gobet gave the position below, which, he said, was from ‘la partie Biélovski-Tcherniev il y a quelques décades en URSS’:

Here, we are told, White played 1 c7-c8=black bishop, after which 2 Nc7 mate cannot be prevented. Under shock, Black at once resigned, forgetting that the rules require a pawn to be promoted to a piece of the same colour.

(7807)

The preceding part of C.N. 1263:

Underhanded Chess by Jerry Sohl (Hawthorn Books Inc. 1973) received little publicity outside the United States, but it is an amusing guide full of ‘devious diversions and stratagems for winning at chess’. A quote from page 6 sets the tone:

‘To win, one must have a touch of the larcenist in his heart, the actor in his soul, the picaroon in his psyche, and the cozener in his brain.’

A remark by Nat (Nathan) Halper (1907-83) on page 136 of the April 1943 Chess Review:

‘In my early career I knew nothing about chess, but had a certain slyness. In my later career I knew nothing about chess, but had a certain cussedness. I never knew enough to know how to win a game, but because of my orneriness and cunning I have been able to tie games with Kashdan, Horowitz, Hanauer, Reinfeld, Bernstein, Ulvestad, Santasiere, M. Green and L. Levy ... And – were they annoyed!’

(8011)

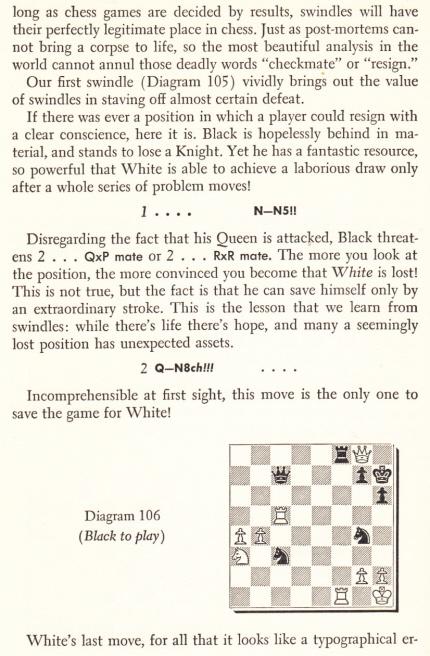

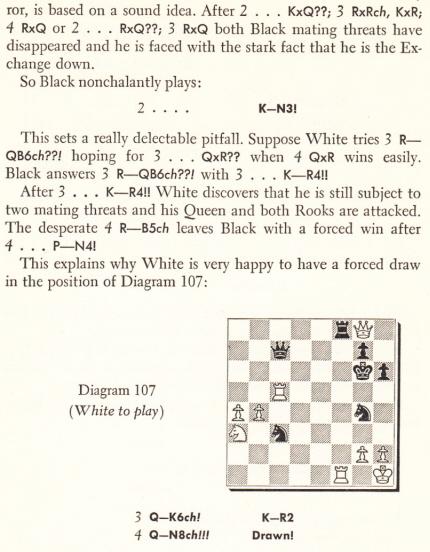

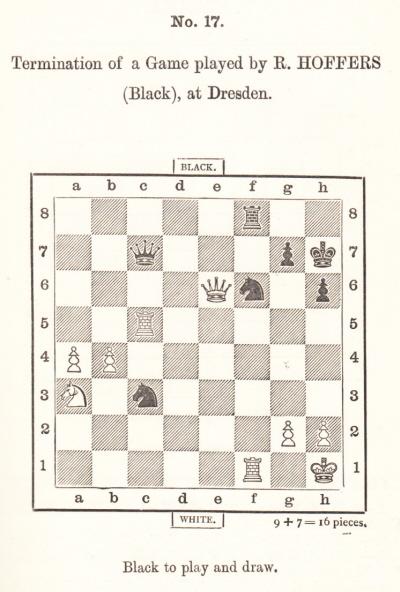

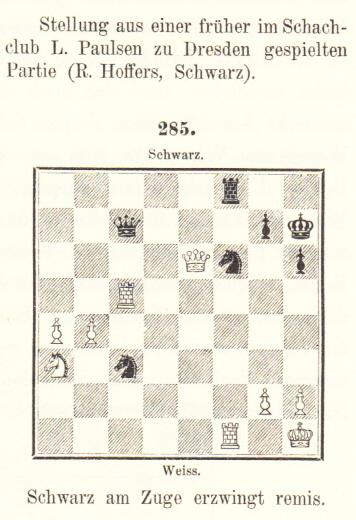

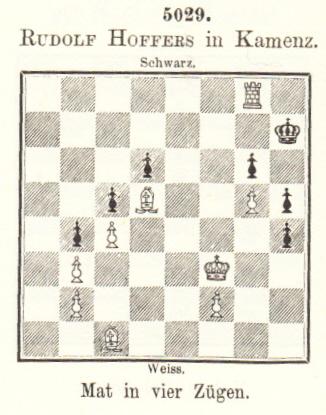

Black to move

‘If there was ever a position in which a player could resign with a clear conscience, here it is.’

So commented I.A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld in Chess Traps, Pitfalls, and Swindles (New York, 1954) in a discussion on pages 127-129:

(Four lines above the diagram on the third page ‘4 R-B5ch’ means ‘4 R-QB5ch’.)

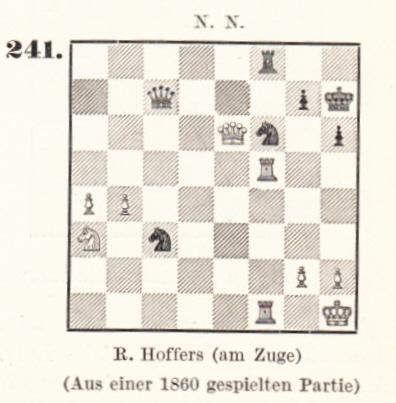

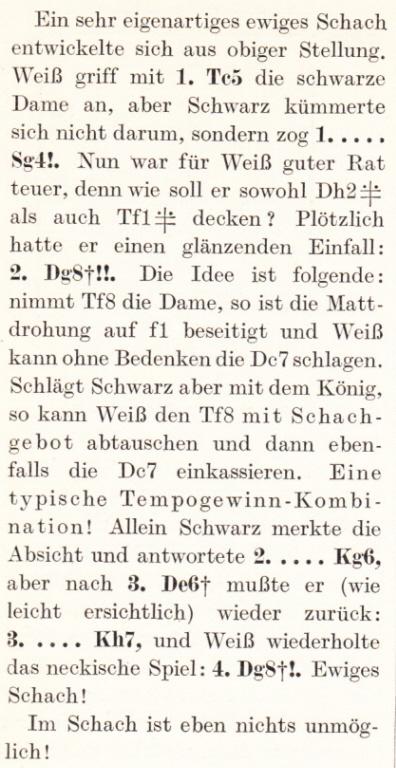

No information was provided about the players or occasion, but the following appeared on pages 107-108 of Kombinationen by Kurt Richter (Berlin and Leipzig, 1936):

In later editions of Kombinationen it was position 271, but the information remained the same: Richter stated that R. Hoffers was White and that the game was played in 1860.

However, on page 119 of A Complete Guide to the Game of Chess by H.F.L. Meyer (London, 1882) R. Hoffers was named as Black, Dresden was given as the venue, and there was no date:

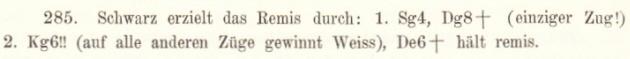

Below is the solution on page 122, in Meyer’s unwonted notation (explained in C.N. 4589):

Hoffers had also been identified as Black, not White, on page 313 of the October 1880 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

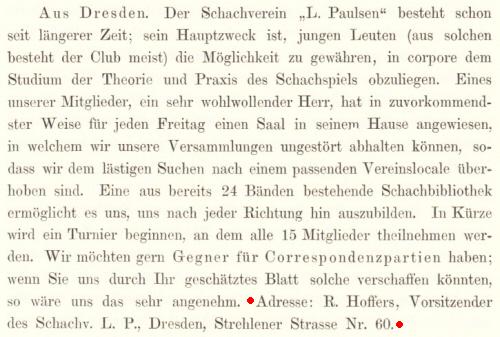

It is unclear exactly how the word ‘früher’ (e.g. ‘some time ago’) should be interpreted. Certainly, the references to Hoffers in the German magazine were clustered around 1880, and we have found nothing about him or the position in any publication circa 1860.

The conclusion was given on page 20 of the January 1881 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

Page 5 of the January 1880 issue had mentioned Hoffers in connection with the Schachverein Louis Paulsen, giving an address in Dresden (Strehlener Strasse 30):

Page 62 of the February 1882 Deutsche Schachzeitung printed a problem by ‘Rudolf Hoffers of Kamenz’ (Kamenz being a town about 40 kilometres from Dresden):

Inevitably, confusion has arisen between Hoffers and Hoffer. For example, page 42 of Chess Techniques by A.R.B. Thomas (London, 1975) labelled the ‘swindle’ position ‘Hoffer-N.N., 1860’.

Other occurrences in print are sought. What, for instance, was the source for the starting position given by Richter (with the white rook on f5 and not yet on c5)?

(8179)

Play went 1...Ng4 2 Qg8+ Kg6 3 Qe6+ Kh7 4 Qg8+ Drawn. No further details have yet been traced concerning this nineteenth-century game involving R. Hoffers.

However, Richard Forster (Zurich) considers that the Horowitz and Reinfeld book was incorrect to classify the play as a ‘swindle’. There was no element of luck, such as a move or plan which worked only because the opponent did not see through it in time. Both sides simply played the best moves, and the spectacular draw by perpetual check was the fair outcome.

Our correspondent adds that Black’s unknown move before Rf5-c5 could be called a swindle if it provoked White to err with the move Rf5-c5, but that was not the thrust of Horowitz and Reinfeld’s text.

(8206)

An article by G.H. Diggle from the July 1982 Newsflash which was given on page 84 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘A fine example of chess longevity was the late O.C. Müller ... He came to England in the early 1880s and for ten years made a meagre living as a professional – but being an excellent linguist he wisely took up translating and interpreting, supplementing his income by Divan Chess. He was an habitué at Purssells (1880-94), Simpsons (1894-1903) and later the famous Gambit Café in Budge Row, where in the ’20s the BM (when in town) spent some pleasant hours losing to the veteran at pawn and move (which was then approaching but not quite on its deathbed) and listening with others to his vast repertoire of anecdotes of days gone by. From a young would-be chess historian’s point of view he was rather irritating in one respect – he would never wear any attempt to turn a monologue into an interview, and “any questions” was simply not on. Once he made a small slip when speaking of the Anderssen-Morphy match, and the BM, bursting to air his knowledge, had the temerity to interrupt. “Surely it was in the sixth game, not the fourth”, piped up the unwary youth. “Indeed?”, replied Müller with great deference, “Personally I vos not there.”

But some of Müller’s opponents in his later days were older even than himself. There was one retired aged clergyman, a fairly strong player but rather deaf and somewhat cantankerous. The BM once saw Müller refute the old cleric’s combination with an unexpected resource, whereupon His Spiteful Reverence barked: “All luck! Sheer luck! You never played for that – it dropped on you like manna from Heaven!” Müller merely winked quietly at the gallery. But on another occasion the old curator of human souls actually scored a win worthy of being “written in letters of gold” in W.R. Hartston’s How to Cheat at Chess. The queens had already been exchanged but “Clericus”, who had an advanced passed pawn, made a series of sacrifices which ensured its promotion. On the eve of “victory”, however, he realized that his new queen would be “all on her own” against two rooks and several minor pieces. Nothing daunted, he “queened” with a tremendous flourish, jumbled up all the remaining pieces on the board as though nobody but a fool could fail to see the game was over, girded up his loins like Elijah the Tishbite, and made for the door at full speed. As his shovel hat disappeared into Budge Row some wit called out “Stop, thief!”, and there was a great roar of laughter.’

(8377)

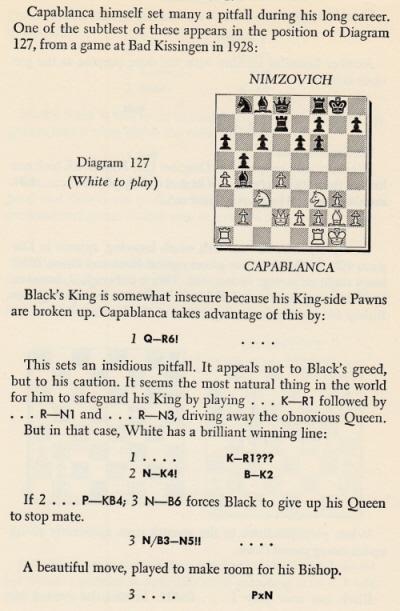

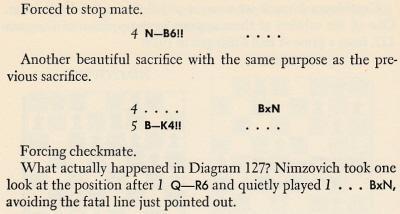

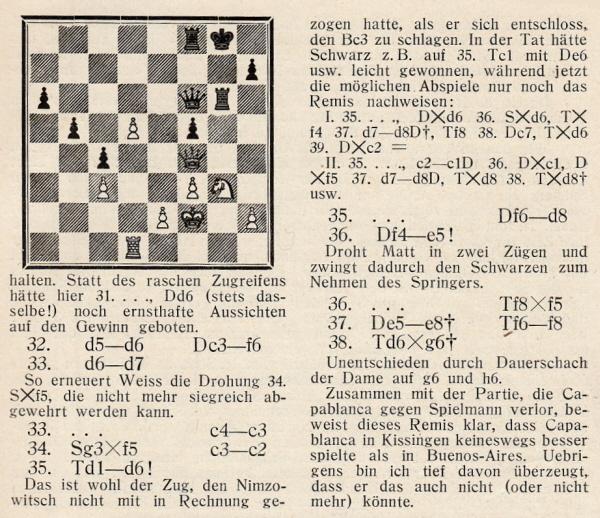

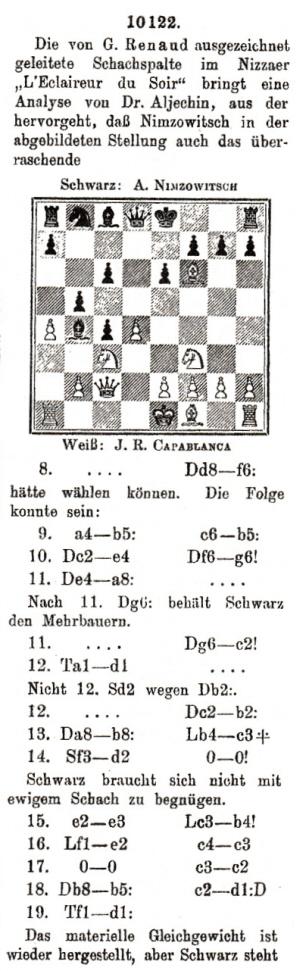

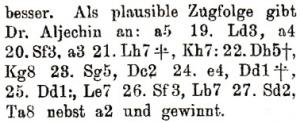

From pages 151-152 of Chess Traps, Pitfalls, and Swindles by I.A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1954):

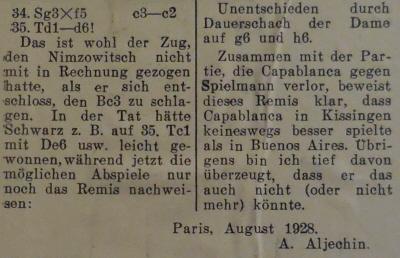

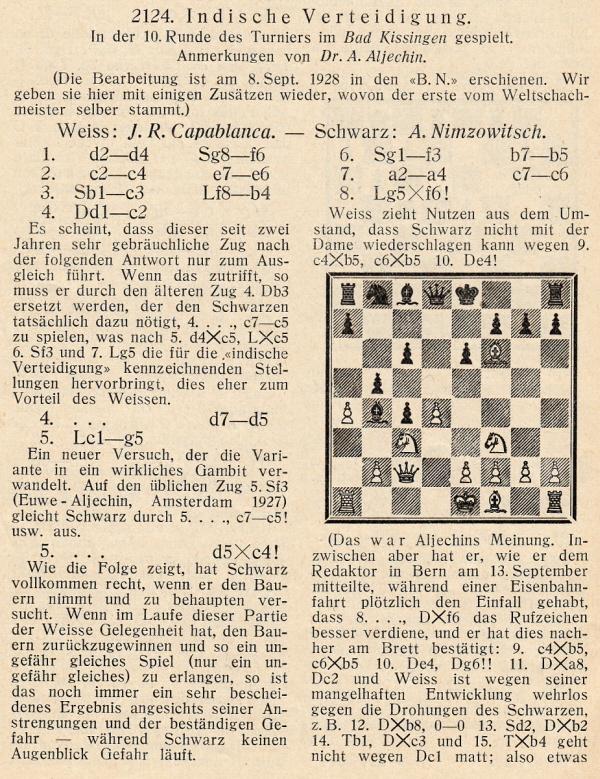

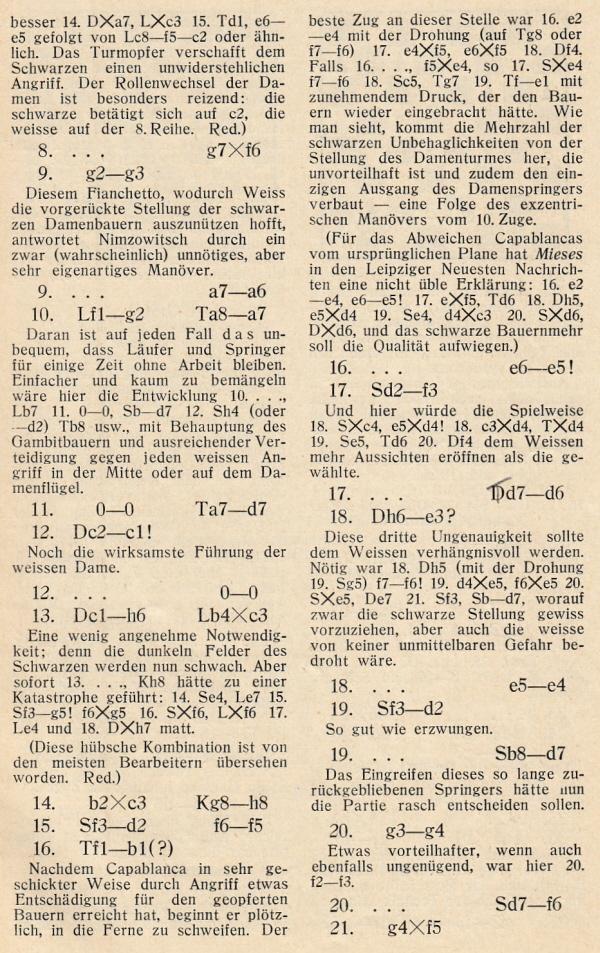

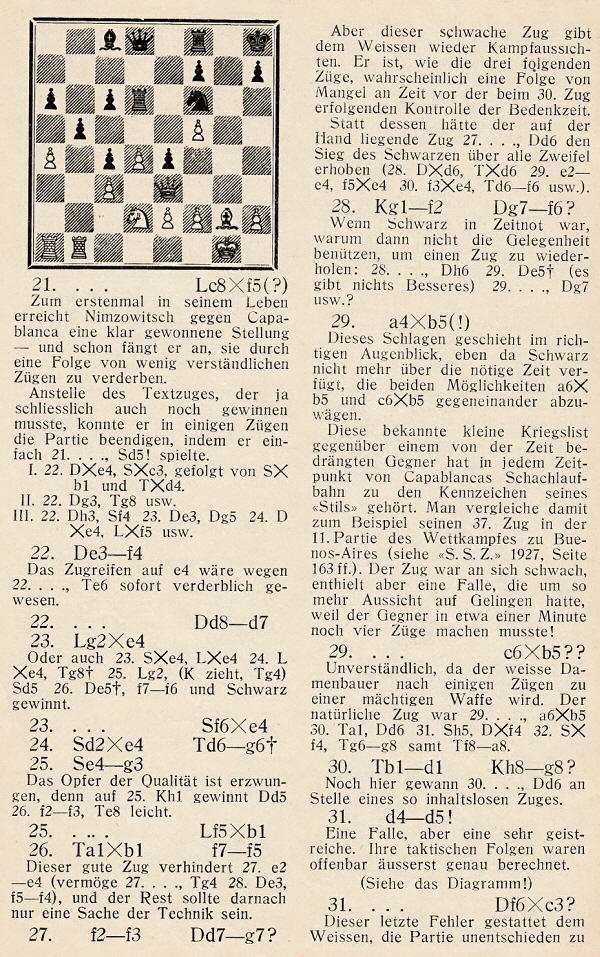

In the initial diagram the white queen should be on c1. We do not know the basis for the co-authors’ statement that after the move Qh6 Nimzowitsch merely ‘took one look at the position’ before ‘quietly’ capturing the knight. Indeed, we cannot say when either player became aware of the mating line; on page 470 of the December 1928 BCM J.H. Blake wrote that it was pointed out by Alekhine.

The world champion annotated the game deeply in the Basler Nachrichten, 8 September 1928:

The full notes, incorporating some further remarks, were reproduced on pages 164-167 of the October 1928 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

A different German version of Alekhine’s notes appeared, via Tidskrift för Schack, on pages 252-255 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, August 1929.

From pages 377-378 of the December 1928 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

When the Deutsche Schachzeitung had annotated the full game on pages 273-274 of its September 1928 issue, the ‘insidious pitfall’ was overlooked, the following being the note to 13...Bxc3:

‘Es drohte Sc3-e4. Dennoch sollte sich Schwarz lieber die beiden Läufer erhalten, z. B. 13...Kh8! 14 Se4 Le7 als Tg8 und Tg6.’

Similarly, the notes in The Field, reproduced on pages 83-84 of the January 1929 Chess Amateur, stated after 13...Bxc3:

‘To stop Kt-K4. Better, however, would have been 13...K-R1 14 Kt-K4 B-K2, followed by ...R-Kt1 and ...R-Kt3.’

On pages 27-29 of Schachjahrbuch 1928 by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1929) the moves 12...O-O 13 Qh6 Bxc3 14 bxc3 Kh8 were given without comment. Nor was the mating trap mentioned in C.S. Howell’s annotations on pages 137-138 of the September-October 1928 American Chess Bulletin.

A detailed set of annotations appeared in Tartakower’s German-language tournament book. See too the coverage of the game on pages 37-41 of Aaron Nimzowitsch 1928-1935 by Rudolf Reinhardt (Berlin, 2010), or pages 39-43 of the English edition (Alkmaar, 2013).

(8594)

Richard Réti’s remark that Emanuel Lasker ‘often deliberately plays badly’ was given in the section on the former world champion in Masters of the Chess Board (London, 1933); on page 124 of the German edition (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1930) the wording was ‘Lasker spielt oft absichtlich schlecht’. See too pages 404-405 of A Chess Omnibus, as well as C.N. 6889. We should like to give the full text of Réti’s original article (‘published after the New York tournament of 1924’).

A detailed study of Lasker’s play has just been published, John Nunn’s Chess Course (London, 2014), and it is unmissable.

In his Introduction (page 7) Nunn writes:

‘... the myth has developed that many of Lasker’s wins were based on swindles, pure luck or even the effect of his cigars. In reality, there was nothing mystical or underhand about his games; they were based on a deep understanding of chess, an appreciation of deceptive positions and some shrewd psychology. Another myth for which there seems no real evidence is that Lasker deliberately played bad moves in order to unsettle his opponents. Certainly Lasker played bad moves, as all chessplayers do from time to time, but the point which struck me when analysing his games was how often he adopted a safety-first strategy. Lasker was a great fighter and had a strong will to win, but his winning efforts hardly ever crossed the boundary into recklessness; in almost every case, he played moves that appeared provocative but were no worse than the alternatives, with the important difference that they were more likely to induce a mistake.’

(8660)

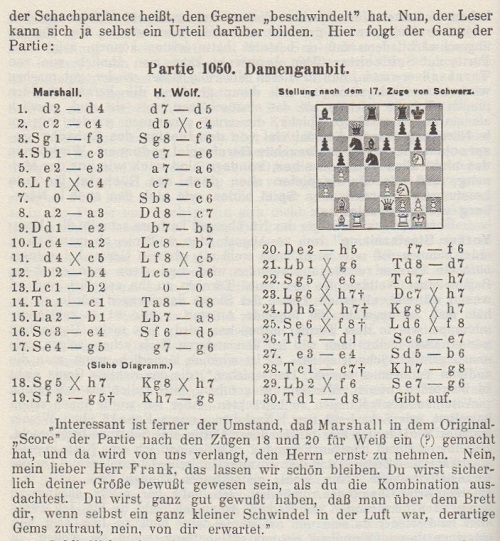

From the third match-game between Janowsky and Marshall, Biarritz, 4 September 1912 (Black to move):

Marshall played 12...Qxf3, and commented on page 50 of Marshall’s Chess “Swindles” (New York, 1914):

‘Taking White completely by surprise, and I heard a murmur of a “swindle”.’

A similar remark was on page 141 of My Fifty Years of Chess by Frank J. Marshall (New York, 1942):

‘Before my opponent answered this surprise move, I heard him whisper, “Swindle!”’

The Introduction to Marshall’s 1914 book had this note on the term:

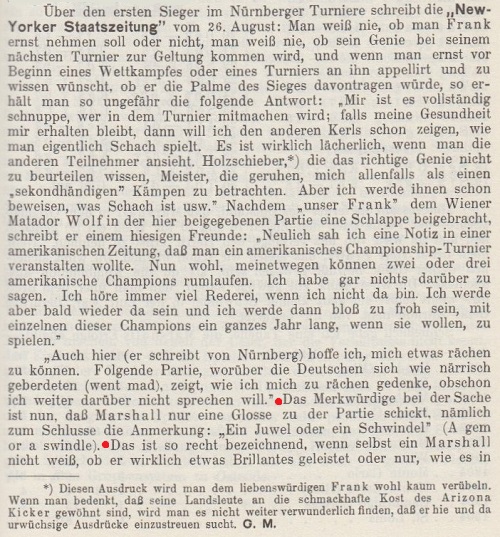

Proceeding in reverse chronological order, we give now an extract from pages 39-40 of the January-February 1907 Wiener Schachzeitung, in connection with Marshall’s game against Heinrich Wolf at Nuremberg, 8 August 1906:

From page 11 of Hermann Helms’ coverage of the Marshall v Tarrasch match on page 11 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 15 October 1905:

‘One thing is sure, and that is, Dr Tarrasch has reduced the possibilities for the famous “Marshall’s swindles” to a minimum.’

Another remark by Helms is on page 85 of volume two of Halpern’s Chess Symposium (New York, 1905) – concerning the position after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 f5 in the 14th match-game between Janowsky and Marshall in Paris, 25 February 1905:

The game with Helms’ notes is on pages 52-53 of Marshall’s Chess “Swindles”.

An earlier occurrence of the term, also in Helms’ journalism, was on page 24 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 6 March 1904:

When was the word ‘swindle’ first used in connection with Marshall’s play?

The following paragraph is from page 51 of Frank Marshall, United States Chess Champion by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 1994):

Soltis did not specify his source or indicate whether the quoted words were his own translation. Can a reader provide the original Russian text? For now, we can give only the following on page 477 of the November 1903 BCM, with ‘rogue’ instead of ‘swindler’:

(9620)

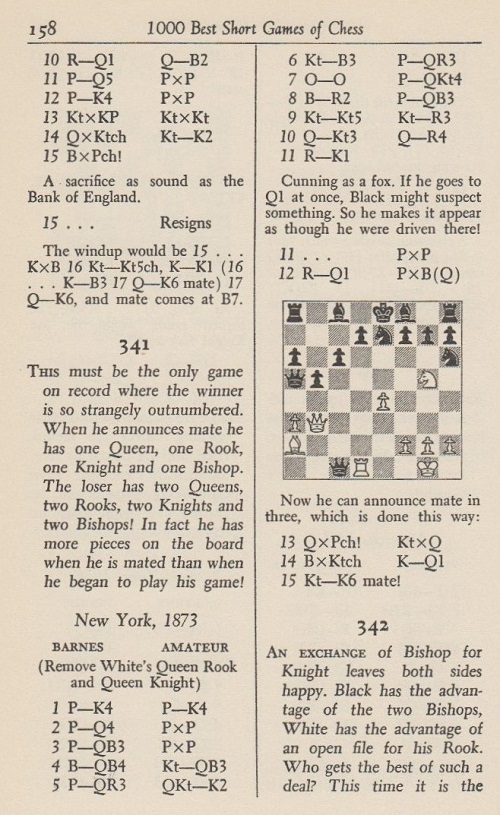

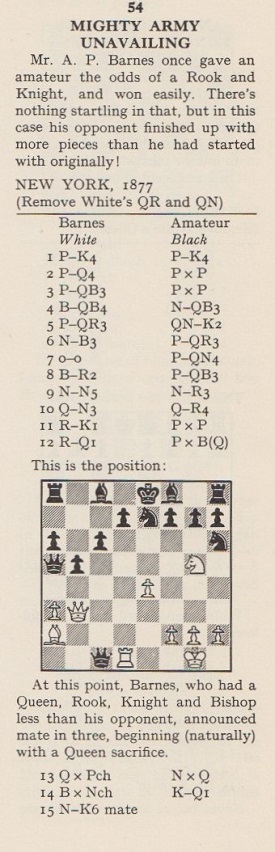

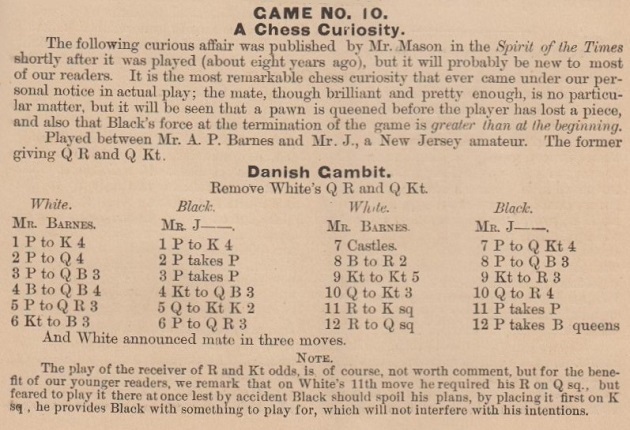

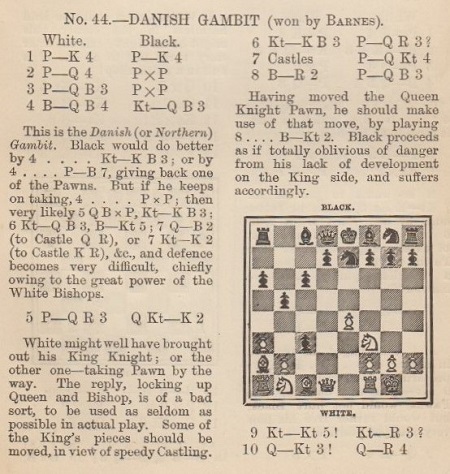

White to move

In this position, wrote Irving Chernev on page 158 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955), White was ‘cunning as a fox’ by playing 11 Re1, and not Rd1.

Chernev also gave the game on page 29 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974), but this time dated 1877:

It is unclear why, in both books, Chernev stated that the venue was New York, given the references below to New Jersey.

The cunning of Alfred P. Barnes in this game was remarked upon on page 29 of Brentano’s Chess Monthly, May 1881:

The game had been published by James Mason on page 483 of Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, 26 December 1874:

However, when Mason included the score on pages 77-78 of Social Chess (London, 1900) it was not presented as an odds game:

(9674)

A similar item, with no date or venue, appeared on page 74 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949).

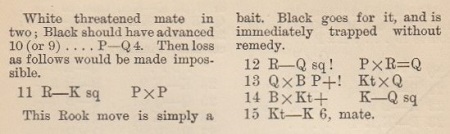

Concerning the Milan Matulović/j’adoube affair, see C.N. 9737.

Chess Review, January 1968, page 24

‘The term “swindle” in chess is so widely used that we have to tolerate it. But it carries the implication we always fight against, i.e. that a player in a theoretically winning position has a sort of moral right to the game; if he fails to see through his opponent’s resourceful play, he says he was “swindled”.

Showing that he hasn’t a moral right to the game is just what the authors are really doing – and doing very well.’

Source: Chess World, January 1957, page 22, in a brief notice regarding Chess Traps, Pitfalls, and Swindles by I.A. Horowitz and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1954). Purdy’s item began: ‘This is the best book on traps yet.’

(9749)

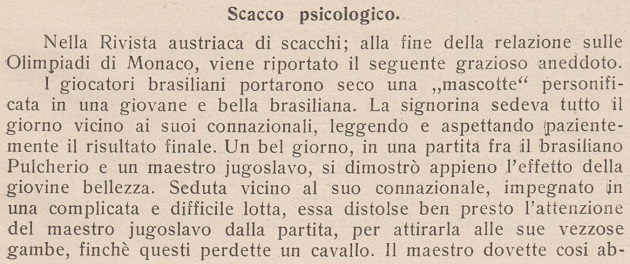

Wanted: information about a finish discussed on pages 132-135 of Chess Traps, Pitfalls, and Swindles by I.A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1954), where it was described as ‘one of the most far-reaching swindles in the history of chess’:

White to move

1 Kf1 Rxa3 2 Bb4 Rxa2 3 Qh6+ Kxh6 4 Bf8+ Kh5 5 g4+ Kh4 6 Be7+ g5 7 Bxg5+ Kh3 8 Nf2+ Kxh2 9 Bf4 mate.

No particulars about the players, date or venue were provided.

(9824)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) notes that the position was given as ‘A. Schlösser-N.N., Meseritz, 1940’ on page 50 of Jaque Mate by Kurt Richter (Barcelona, 1972). The winner’s explanation of the trap was quoted.

The item was on pages 43-44 of the original German edition, Schachmatt (Berlin, 1950). No source was given, but we have found the original text on the inside back cover of the 1 July 1940 issue of Deutsche Schachblätter, in a feature entitled ‘Schachliche Kurzgeschichten’:

(9828)

From the article ‘Luck in Chess, the Clock, the Bad Bishop’ by C.J.S. Purdy on pages 189-190 of Chess World, September 1957:

‘Chess is in the last resort a battle of wits, not an exercise in mathematics. Theory helps you; but you have to fight. Hence our contempt for the stupid word “swindle” in chess.’

(10216)

An episode in the 1936 Munich Olympiad was related on pages 159-160 of the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, October 1936:

The Austrian magazine referred to was the Österreichische Schachzeitung, and the relevant passage on page 5 of the September-October 1936 issue is given below, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library:

Gerbec did not name the player on the Yugoslav team who lost to Pulcherio after being distracted by the beauty of a young Brazilian ‘mascot’. Pages 106-107 of part two of Schach-Olympia München 1936 by Kurt Richter (Berlin and Leipzig, 1937) record that in round 16, played on 28 August, Pulcherio (Black) defeated Imre König. We have not found the game-score.

(11285)

See too the references to Labatt v Marshall and Alekhine v Braumann in the Factfinder.

Concerning a chess magazine which regularly deceived its readers about us (the BCM, under the editorship of Bernard Cafferty), see Rebuttals.

As shown in our feature article on him, the writings of G. Koltanowski were liberal with accusations of sharp practice. Two examples from his 1972 booklet With the Chess Masters:

Pages 15-16: The best part of two pages are devoted to a story of how L. Steiner cheated against Colle at ‘the Budapest International, 1928’. Neither player was there.

Pages 67-68: Another cheating anecdote, according to which Dyckhoff pretended only to have drawn against John at Hanover, 1902, so that his close rival Bernstein would not go for a win against Kagan. Yet Dyckhoff and John did only draw.

The opening sentence of our article on Copying:

Some cheat at the chessboard, others at the keyboard.

Prompted by the swirl of unverified and unverifiable claims about online cheating, we suggest the following:

Accusations need corroboration. Insinuations need expurgation.

(12007)

An addition on 29 October 2024 (see also Chess Thoughts):

Establish misconduct and then go public, yes. Pluck an angle and then go angling, no. Inquisitorial not piscatorial.

Having previously asked readers to imagine themselves as the editor of a chess quotations book (C.N. 11994) and of a single-volume chess encyclopaedia (C.N. 12035), we now invite them to assume the role of a mainstream journalist commissioned to produce a chess article on recent allegations of online cheating. Where to look for the essentials? Where to find output in which opinions, biased or not, do not leap-frog over facts?

The journalist may dive in at some random point proposed by Google, only to find barely comprehensible arguments deployed with links to barely comprehensible X/Twitter posts or YouTube videos, as various parties and partisans compete with declarations, interrogations, accusations and insinuations. But where are a placid, objectively formulated overview and chronology of how any given point was reached? In brief, where is the journalism?

This is not new. Nearly a decade ago, Nigel Short wrote in New in Chess about the differences between male and female chessplayers, and an outcry ensued, unhurriedly. If a journalist today seeks a reminder of the case, where to go? Should Google prove unhelpful, it may seem sensible to turn to a ‘standard’ source such as the Wikipedia entry on Short, but that fails too. It has 70 words on the affair and three endnotes, all three being links to ‘outcry’ articles by non-specialist writers in three UK newspapers, the Independent, the Guardian and the Daily Telegraph; all three articles, as it happens, were dated 20 April 2015. The New in Chess piece had been published about a month previously.

Wikipedia does not relate what Short had written in New in Chess, even though the full text was reproduced by ChessBase not long after the tumult began, and is still there. Nor does Wikipedia display awareness of Short’s follow-up article in New in Chess, which was, in part, a reply to the assertions in the three UK newspapers. The media had gorged themselves and, in terms of actual arguments, the second New in Chess article was, so to speak, even more ignored than the first one. Vive l’indifférence.

That was the shallow treatment of a controversy in 2015, and one looks in vain, even today, for a plain, factual account of it. How will the media of 2024 be judged in future years for their handling of the present cheating cacophony? Who will emerge with honour for showing care over facts and respect for fair play? Who will work hard to clarify the issues for the public’s benefit? And when will the process start?

(12060)

Addition on 14 November 2024:

An example of how the public record may be skewed is provided by the reaction, or lack thereof, to Nigel Short’s follow-up article (‘A Beautiful Minefield’) on pages 36-37 of the 4/2015 New in Chess, where he wrote, for instance:

‘On 20 April an article appeared in The Daily Telegraph entitled “Nigel Short: Girls Just Don’t Have the Brains to Play Chess”. Never mind the fact I didn’t say that, it was a catchy headline to set me up as a misogynist pantomime villain. In extraordinary rapid succession came a whole series of similar articles, in The Guardian, The Times, The Independent, many with totally fabricated quotes and grotesque distortions – such as the Daily Mail’s “Women aren’t smart enough to play chess because the game requires logical thinking, says British Grandmaster”, despite me having said nothing at all about logic.’

C.N. 9344 quoted that rebuttal, but where else can it be found on the Internet? We see only one place, at the English Chess Forum, where, on 18 December 2020, Short reproduced the full text of ‘A Beautiful Minefield’.

From C.N. 9254 (written a decade ago, in intentionally utopian style):

Of all the lessons to be learned from the shambolic, sprawling rumpus over ‘Vive la Différence’ [a New in Chess article by Nigel Short on women’s chess ...] a neglected one is mentioned here, in the context of any current issues (as opposed to history and lore): the lack of a proper online chess forum where topical controversies can be discussed in depth; where comprehensive and comprehensible coverage is founded on facts and informed opinions; where contributions bear the writer’s real name; where hearsay is absent; where wit is welcome but glib illiterates are not; where Internet links are supplied only if they lead to something worthwhile; where irrelevancy and repetition are avoided; where strong criticism of people and of ideas is expressed solely if based on substantiated information; where all relevant sources are cited; where points are not deemed true, or even noteworthy, merely because they come from the mainstream media; where press articles by non-chess-specialists are treated not with automatic gratitude but with particular caution; where misquotation is excoriated; where the debate, however lively, is moderated with rigorous even-handedness; where good linguistic standards are ensured; where contributors and readers are treated with the respect that they deserve; where anyone, including top-level masters, would be proud to have a contribution posted.

Wanted: one topical chess forum where 100% of the contributions are worth reading, and not 100 forums where 1% are.

No topical forum along remotely similar lines has yet emerged. The current battles over online cheating are a grimly undignified, barely intelligible mess with, as their hub, nothing better than X/Twitter.

There must be a better way.

(12166)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.