Edward Winter

William Lewis

Section 2: Inflation and proposals to reform terminology

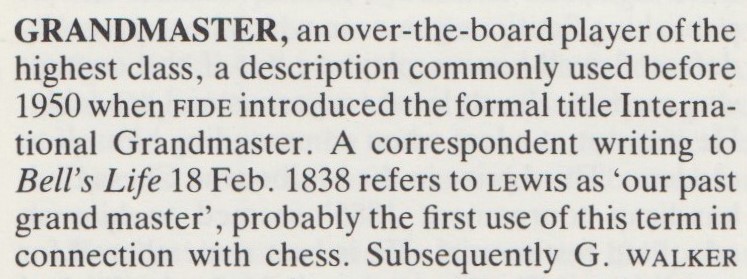

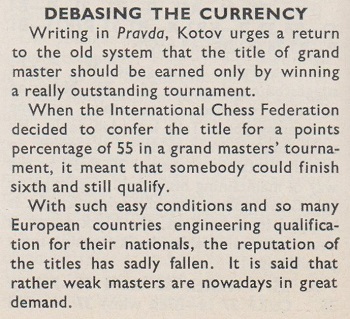

From page 132 of the Oxford Companion to Chess by D. Hooper and K. Whyld (Oxford, 1984), in the entry on ‘Grandmaster’:

‘A correspondent writing to Bell’s Life 18 Feb. 1838 refers to Lewis as “our past grand master”, probably the first use of this term in connection with chess.’

(848)

In an article on page 19 of the March 1989 CHESS Nigel Davies writes:

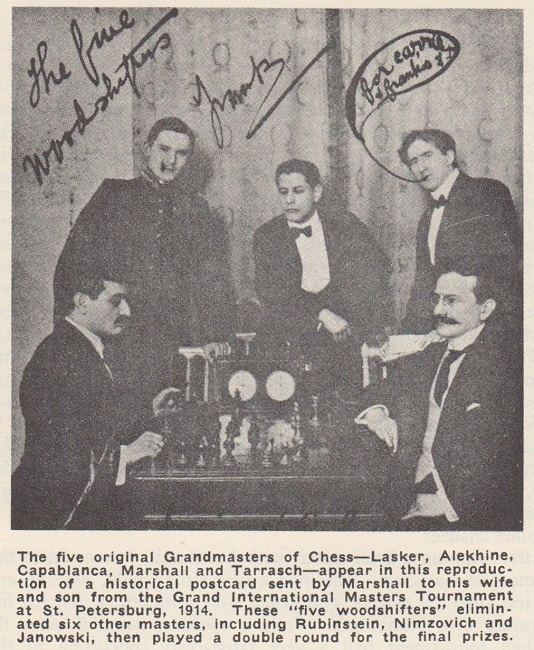

‘The original grandmasters, however, were created by the Tsar at the great St Petersburg tournament of 1914. They were Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Marshall and Rubinstein, arguably the five best players of the day, and of whom three held the world championship at one time or another.’

For Rubinstein read Tarrasch; A.K.R. came nowhere in the St Petersburg tournament. The Tsar’s conferment of the five Grandmaster titles is a recurrent story in historical works, but what proof of it is there in Russian literature of the time?

(1810)

Some chess writers contend that Tsar Nicholas II awarded the title of Grandmaster to Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Marshall and Tarrasch, the five finalists at St Petersburg, 1914. Does evidence exist to corroborate this?

(1998)

Louis Blair (Knoxville, TN, USA) believes that the source of the Tsar story is almost certainly page 21 of Marshall’s My Fifty Years of Chess (New York and Philadelphia, 1942), a book in which Fred Reinfeld is known to have played an extensive role. Our correspondent quotes a passage (referring to the period of the St Petersburg, 1914 tournament) from page 198 of Nicholas II by Dominic Lieven (New York, 1993):

‘The imperial family spent April and May 1914 in the Crimea. The Council of Ministers no longer had an effective chairman, but the monarch was hundreds of miles from his capital with communications passing by post and courier.’

(2080)

We note that both the Wiener Schachzeitung and the Deutsche Schachzeitung were using the term ‘grandmaster (Großmeister) tournament’ to describe St Petersburg, 1914 before the event began.

Page 28 of the January 1914 Deutsche Schachzeitung called Capablanca ‘der kubanische Großmeister’. (This news item also reported that in a simultaneous display at St Petersburg, in 1913, a draw had been scored by a ten-year old, Prince Gedroiz, who was ‘the son of a lord-in-waiting of the Imperial Court’.)

(2101)

Page 119 of the second volume of Complete Games of Alekhine by V. Fiala and J. Kalendovský (Olomouc, 1996) offers a strange twist to the question of whether Tsar Nicholas II conferred the title of ‘grandmaster’ on the finalists of the St Petersburg, 1914 tournament. The book quotes an interview with Alekhine in El Debate of 28 May 1922. Asked whether he had started to play chess at a very early age, he replied:

‘I have played chess since the age of seven and when I was 14 I was named a master by the Tsar himself when I won the national tournament in St Petersburg.’

For 14 read 16. The event in question was the St Petersburg, 1909 All-Russian tournament, but is there any more evidence of the Tsar’s involvement in that event than there is, at present, concerning St Petersburg, 1914?

(2139)

On page 265 of Chess Digest Magazine, December 1974 Larry Evans, a chess writer not famed for accuracy, stated: ‘Czar Nicholas I coined the title of “Grandmaster” when he sponsored the great St Petersburg tournament in 1914.’ Nicholas I lived from 1796 to 1855.

With regard to the origin of the term ‘grandmaster’, Znosko-Borovsky dealt with the issue extensively on pages 221-222 of the November 1925 L’Echiquier. His conclusion was that the title was over-used:

‘In truth, the only players whom we should consider grandmasters are Capablanca, Alekhine, Lasker, perhaps Marshall (if we wish to forget his misfortunes in match play) and, on account of their former successes, Tarrasch and Rubinstein. All the others should be regarded as plain masters.’

In C.N. 2080 a correspondent suggested that the story about the grandmaster title being conferred by Tsar Nicholas II at St Petersburg, 1914 probably originated with Marshall’s 1942 book My Fifty Years of Chess. We have now found, however, a slightly earlier occurrence. In an article ‘Things I Never Knew’ on page 149 of Chess Review, October 1940 Fred Reinfeld quoted the following passage from an article by Robert Lewis Taylor in The New Yorker of 15 June 1940:

‘[A grandmaster] is a master who has either won, placed, or showed in a major tournament or been named a Grand Master by Tsar Nicholas II of Russia. The Tsar, it seems, was a rather arbitrary chess fan who enjoyed watching matches, and when he saw a player he liked the looks of, he just slapped the title on him.’

Given Reinfeld’s involvement in Marshall’s autobiography, it may be wondered how the Nicholas II story found its way into the book.

The Chess Review article shows that on his day Reinfeld could be scathing:

‘The author is one Robert Lewis Taylor, whom The New Yorker describes (with unnecessarily brutal frankness) as A Reporter at Large. Mr Taylor’s style is compounded of breathless inanities smothered in pixillated whimsy. What matter-of-fact detail he presents is vitiated by a slick and phony innocence which forever seems to be saying, “Terribly quaint, my deah!” One’s irritation is increased by the numerous errors which are liberally strewn over every page. Presumably it is a sign of sophistication to hash up even the simplest set of facts, and such elementary accuracy as might be found in the Penmanship lesson of a 1A class is beyond the powers of A Reporter at Large.’

(Kingpin, 2001)

Books continue to claim, without substantiation, that the title of ‘grandmaster’ was first conferred by Tsar Nicholas II at St Petersburg, 1914. The matter was discussed on pages 315-316 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves and pages 177-178 of A Chess Omnibus, and we have still found no earlier occurrence of the story than in an article by Robert Lewis Taylor in The New Yorker, 15 June 1940.

To pose a broader question: do 1914 sources contain references to Tsar Nicholas II in connection with any aspect of the St Petersburg tournament?

(5144)

From page 32 of the February 1943 BCM:

‘Vasily Smyslov is a student at the Moscow Aircraft Institute, and is 21 years old. Nevertheless he has earned a place among the six chess grand-masters of the Soviet Union. … Great maturity, level headedness and confidence mark Smyslov’s playing in spite of his youth, and many of his admirers predict that he will be a candidate for the world championship.’

(2484)

Little-known nineteenth-century occurrences of the term ‘grandmaster’ are always welcome. Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) forwards one from page 324 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1854:

‘Many a player can conduct a game without the board coolly and steadily, but who, save De la Bourdonnais, under such circumstances, invented attacks profound in conception, brilliant in execution, and enduring upon analysis? Who but the Chess Grand-Master could have contested a game without the board against a player like Boncourt, with the remotest chance of success?’

(5152)

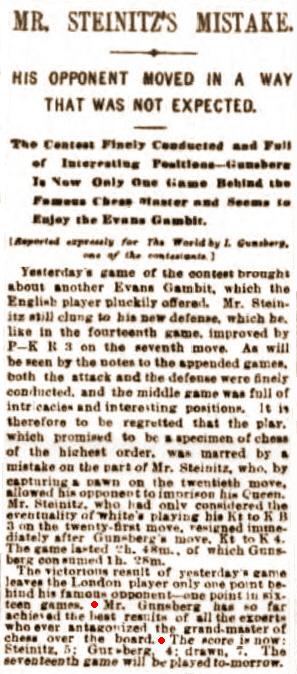

The following item, submitted by John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA), was written by Gunsberg on page 6 of The World, 16 January 1891:

(7779)

Raymond Keene, naturally enough, has continued to spread the Tsar Nicholas II story. It appeared twice in his unspeakably awful book The Official Biography of Tony Buzan (Croydon, 2013), on pages 137 and 415:

‘Chess, of course, was the template for royal endorsement of the Grandmaster title, when Czar Nicholas II conferred the original chess Grandmaster titles on Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine Tarrasch and Marshall at St Petersburg in 1914.’

‘In 1995, paying homage to the initial award of the chess Grandmaster title by Tzar Nicholas II, the Mind Sport of Memory was granted Royal patronage by Prince Philip of Liechtenstein.’

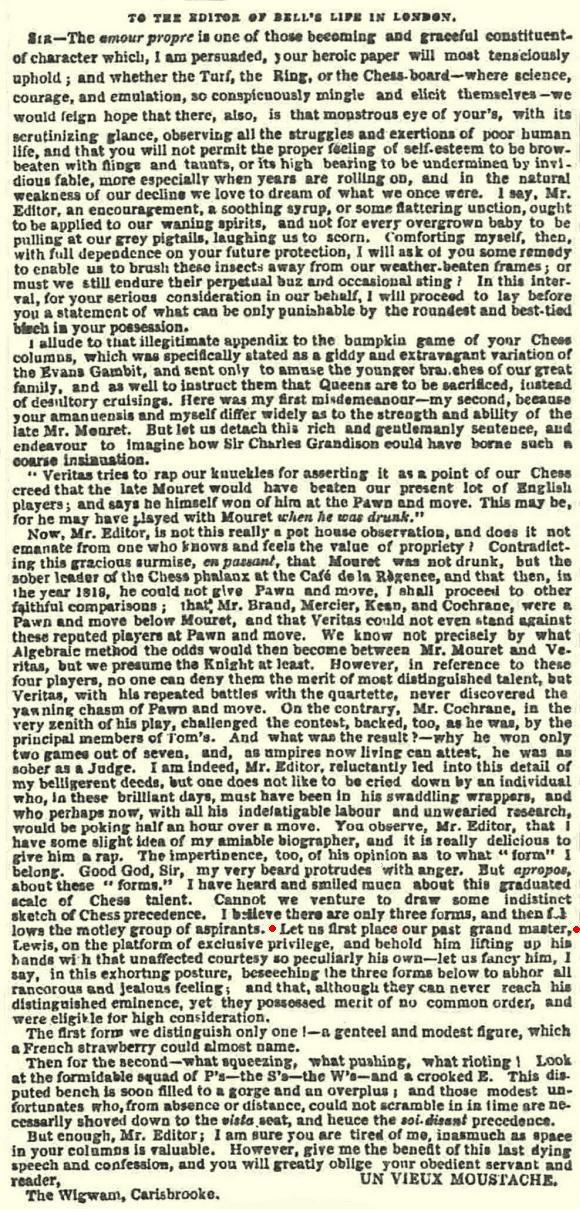

Following publication of the first edition of the Oxford Companion to Chess by David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld (Oxford, 1984), C.N. 848 quoted from the entry on ‘Grandmaster’ (page 132):

‘A correspondent writing to Bell’s Life 18 Feb. 1838 refers to Lewis as “our past grand master”, probably the first use of this term in connection with chess.’

On page 156 of the second edition of the Companion (Oxford, 1992) ‘grand master’ was changed, incorrectly, to ‘grandmaster’.

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) provides the full letter, from page 4 of the 18 February 1838 issue of Bell’s Life and Sporting Chronicle, contributed by ‘Un vieux moustache, The Wigwam, Carisbrooke’:

The relevant passage:

‘I have heard and smiled much about this graduated scale of Chess talent. Cannot we venture to draw some indistinct sketch of Chess precedence. I believe there are only three forms, and then follows the motley group of aspirants. Let us first place our past grand master, Lewis, on the platform of exclusive privilege, and behold him lifting up his hands with that unaffected courtesy so peculiarly his own – let us fancy him, I say, in this exhorting posture, beseeching the three forms below to abhor all rancorous and jealous feeling; and that, although they can never reach his distinguished eminence, yet they possessed merit of no common order, and were eligible for high consideration.’

William Lewis (detail from opposite page 197 of the New York, 1859 edition of F.M. Edge’s book on Morphy)

There have come to light no pre-1838 occurrences of the term ‘grand master’ or ‘grandmaster’ in a chess context, or any pre-1984 mentions of the Bell’s Life citation. The Companion should thus continue to receive full credit for a significant discovery, and no honest writer would hesitate to give such credit.

Under the title ‘Grandmasterly research’ Raymond Keene wrote on page 5 of The Times, 7 November 1994 about claims that the grandmaster title was created by Tsar Nicholas II at St Petersburg, 1914, and he then added:

‘Following up a clue from the Oxford Companion to Chess, Barry Martin, chess captain of the Chelsea Arts Club, has now demonstrated that the term is considerably older.

Martin’s research shows that in Bells Life [sic], a popular Sunday paper, of February 18, 1838, a leading British player, William Lewis, is referred to as “our past grandmaster” [sic]. Here is a sample of play by the man whom the latest research indicates to have been the first player described as a grandmaster in print.’

Barry Martin had not demonstrated or researched anything. In an article about Staunton in the October 1994 CHESS he had merely given the Bell’s Life quote about Lewis (see page 34), without bothering to acknowledge that it had been published by the Companion a decade previously. Nor was the Companion credited when Martin’s article was reproduced on pages 191-201 of Staunton’s City by Raymond Keene and Barry Martin (Aylesbeare, 2004).

It is also worth dwelling on Keene’s deceitful introductory words in The Times:

‘Following up a clue from the Oxford Companion to Chess, Barry Martin ... has now demonstrated ...’

The Companion did not supply ‘a clue’. It supplied the exact relevant text supported by a precisely dated reference.

Worse was to follow. On page 100 of The Spectator, 4 July 1998 Keene made no mention of the Companion and affirmed flatly:

‘Lewis, according to research by Barry Martin, the secretary of the Staunton Society, was the first player to be described as a grandmaster.’

(8298)

Summary:

From page 132 of the first (1984) edition of the Oxford Companion to Chess:

According to Raymond Keene, that entry gave his friend and co-author Barry Martin ‘a clue’, after which, through ‘research’, Martin ‘demonstrated’ (in 1994) that in Bell’s Life on 18 February 1838 Lewis was referred to as ‘our past grandmaster’.

Chess Problems, Play and Personalities by Barry Martin (Beddington, 2018) was discussed briefly in C.N. 11186.

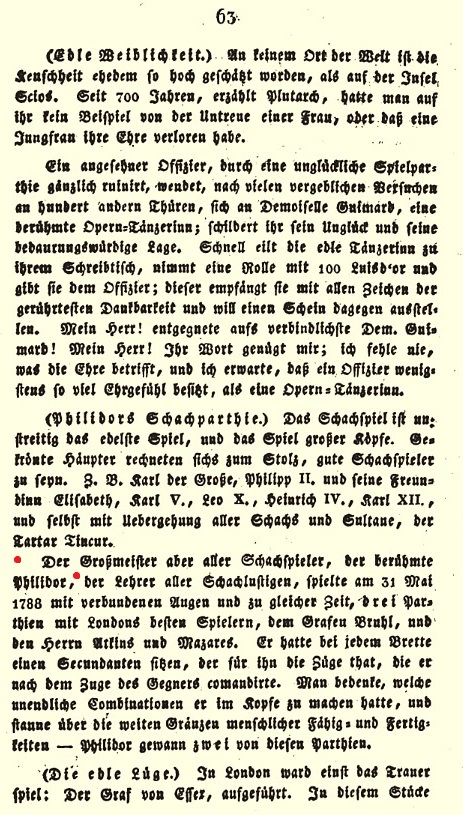

Nick Pope (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) sends the following in relation to Philidor from page 63 of volume three of Lesefrüchte, belehrenden und unterhaltenden Inhalts (Munich, 1828):

(11967)

Chapter XI (pages 53-56) of Lessons from My Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1958) was entitled ‘I Become a Grand Master’, and on page 53 he reiterated a claim already made on page xv: that as a result of winning Hastings, 1935-36 he ‘was officially a grand master’. What is the factual basis of that statement?

Fine also asserted on page 53 that after his first-round victory over Flohr ‘first prize was never in any doubt’. He annotated the game not only in Lessons from My Games but also on pages 3-4 of the January 1936 American Chess Bulletin and on pages 166-167 of CHESS, 14 January 1936.

(8566)

On the front cover and the title page of Bréviaire des échecs Tartakower was described as ‘Grand maître international’:

(9180)

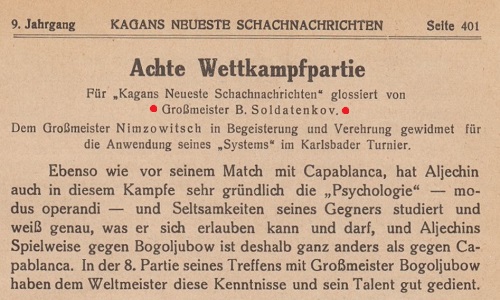

An illustration of how casually the term ‘grandmaster’ (in this case ‘Großmeister’) was sometimes used is on page 401 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, December 1929:

(9203)

Many chess books and articles unquestioningly state that the first five official grandmasters were the finalists at St Petersburg, 1914, and that they received the honour from Tsar Nicholas II. At first sight, there may seem no reason to doubt the story, given what appeared on pages 20-21 of My Fifty Years of Chess by Frank J. Marshall (New York, 1942):

However, complications have been mentioned in C.N. items over the years: the claims that Marshall’s autobiography was ghosted, the failure to discover any pre-1940 version of the story, and the Tsar’s absence from St Petersburg during the 1914 tournament.

Even cumulatively, those points naturally do not suffice to disprove the story about Nicholas II, but they do suggest a verdict of ‘not proven’ and that, at least, the tale should not be repeated without reservation. Alas, few chess writers like expressing reservations or surrendering the opportunity for name-dropping.

No Russian-language sources dating from 1914 have been traced which shed light on the ‘grandmaster title’ affair. Nor has it been possible, so far, to examine the writings (i.e. diaries) of the Tsar himself for the relevant period. We have the Journal intime de Nicolas II (Paris, 1934), but it begins shortly after the St Petersburg, 1914 tournament.

Nor has positive information been found in secondary sources, such as the biographies of the Tsar by Marc Ferro, Dominic Lieven and Edvard Radzinsky.

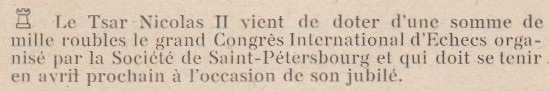

That Nicholas II had involvement of some kind with St Petersburg, 1914 is shown by a brief paragraph on page 79 of La Stratégie, February 1914:

(9317)

See too C.N. 9318.

From page 230 of How To Play Winning Chess by John Saunders (London, 2007):

‘The title of grandmaster first came into frequent use in chess when Tsar Nicholas II conferred it upon the participants of the 1914 St Petersburg chess tournament. The five players – world champion Emanuel Lasker, future champions José Raúl Capablanca and Alexander Alekhine, plus Siegbert Tarrasch and Frank Marshall – were the leading players of their day and fully deserved the honour.’

The same text, with the same photograph of the Tsar, is on page 236 of The Practical Step-by-Step Guide to Chess & Bridge by David Bird and John Saunders (London, 2010) and on page 236 of the same authors’ The Complete Step-by-Step Guide to Chess & Bridge (London, 2015). The chess content of the three books is more or less identical.

As mentioned in C.N. 9317 (see above), the Tsar story lacks proof and should not be repeated without reservation.

(9466)

The same material about the Tsar appeared on pages 106-107 of another repackaging: Advanced Chess by John Saunders (London, 2009).

From Ola Winfridsson (São Paulo, Brazil):

‘I have browsed through some of the early issues of Tidskrift för Schack (Sweden) for instances of the term “stormästare” (grandmaster) prior to the St Petersburg, 1914 tournament.

On page 141 of the 6/1907 issue the games section began with “Stormästareturneringen i Ostende” (The Grandmaster Tournament in Ostend), and page 50 of the 2/1907 issue had this news item:

“Ostende. Som förut är nämnt skall årets turneringar här börja redan den 15 maj. Turneringsledare blir L. Hoffer. Föreslagna äro: en stormästareturnering med 6 deltagare, 4 omgångar och 10.000 fr i priser samt dessutom 1.200 fr som ersättning för omkostnader; en mästareturnering med 30 deltagare ...” [“Ostend. As previously mentioned, this year’s tournaments will begin as early as 15 May. The tournament director will be L. Hoffer. The following are proposed: a grandmaster tournament with six players, quadruple round-robin ...; a master tournament with 30 participants ...”]

That item also stated:

“Segraren i stormästareturnering skall erhålla titeln ‘Turnier-Champion’ och erhåller som sådan guldmedalj och diplom.” [“The winner of the grandmaster tournament will receive the title ‘Turnier-Champion’ and, as such, receive a gold medal and a diploma.”]

The use of “stormästareturnering” without further explanation suggests that “stormästare” was already a familiar term. I can find no reference in Tidskrift för Schack to Tsar Nicholas II having bestowed the title of Grandmaster on the five participants in the final phase of the St Petersburg, 1914 tournament.’

In his extensive coverage of the Ostend congress in The Field, Hoffer referred to the main event as the ‘Championship Tournament’. The book by the winner, Tarrasch, was entitled Das Champion-Turnier zu Ostende im Jahre 1907 (Leipzig, 1907). Throughout its 1907 coverage, La Stratégie used the term ‘tournoi-championnat’.

(9475)

An extract from C.N. 9500:

The dust-jacket of Players and Pawns (Chicago and London, 2015) states that ‘Gary Alan Fine is the John Evans Professor of Sociology at Northwestern University’ and introduces his book thus:

‘A chess match seems as solitary an endeavor as there is in sports: two minds, on their own, in fierce opposition. In contrast, Gary Alan Fine argues that chess is a social duet: two players in silent dialogue who always take each other into account in their play. Surrounding that one-on-one contest is a community life that can be nearly as dramatic and intense as the across-the-board confrontation.’

Beyond such woolliness, the book is striking for a heavy USA-centric approach, the author’s unfamiliarity with chess history and lore, and a staggering lack of discernment in the sources cited.

As demonstrated by the concluding ‘Notes’ section (pages 227-261), the Professor has no interest in, or access to, primary sources and makes do with material unquestioningly derived from familiar books and webpages which are themselves derivative. Those ‘sources’ in the Notes section include an Internet quotations site (itself devoid of sources) and such embarrassments as ‘Internet Chess Club discussion boards, 2010’.

...

Our minuscule sample from Players and Pawns concludes with a line from page 169, regarding the title ‘grandmaster’:

‘... in 1914 Czar Nicholas II awarded the title in Russia. It became an official designation in 1950 by edict of the World Chess Federation.’

The source for that information is specified, on page 255, as ‘Olson, The Chess Kings, 95’. Yet what appears on page 95 of The Chess Kings by Calvin Olson (Victoria, 2006) is something very different:

‘The story regarding the Czar has no foundation and must be relegated to the category of fiction.’

Information about Tsar Nicholas II and the ‘Grandmaster’ title has yet to be found in Russian sources at the time of the St Petersburg, 1914 tournament, but Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada) notes a Soviet perspective by Lev Travin on pages 4-5 of the 14/1974 issue of 64:

Our correspondent has translated the relevant section, at the start of the article:

‘This international tournament was held in 1914 and featured an outstanding entry. It was organized by the St Petersburg chess circle, which had just moved into a spacious new building at 10 Liteyny Prospekt.

The organizers’ intention was to make it the largest chess event of the day, and it was therefore decided to invite only grandmasters.

At that time, the term “grandmaster” was reserved for players who had gained at least one first prize in a major international tournament. There were very few such players. With the exception of the 77-year-old Winawer, who had retired from tournament chess, there were only two players in Russia who held the title: Akiba Rubinstein of Łódź, and the Moscow lawyer Ossip Bernstein.

The other Russian masters were invited to participate in an event known as the All-Russian tournament, the winner of which would be admitted to the grandmaster tournament ...’

(9520)

From The Field, 13 March 1909, concerning St Petersburg, 1909:

‘The Czar has generously given an objet d’art and 1,000 roubles in specie towards the prize fund.’

The 20 March 1909 issue of The Field reported:

‘The prizes added by the Czar are not intended, as erroneously stated, for the masters only, but the 1,000 roubles go to the masters, and the objet d’art to the first prize winner of the strong National Tournament. The committee will probably take the equitable step to apportion the 1,000 roubles to all the players pro rata of their scores.’

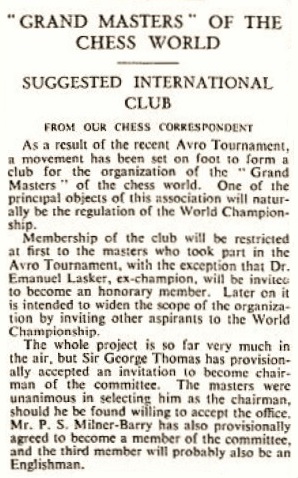

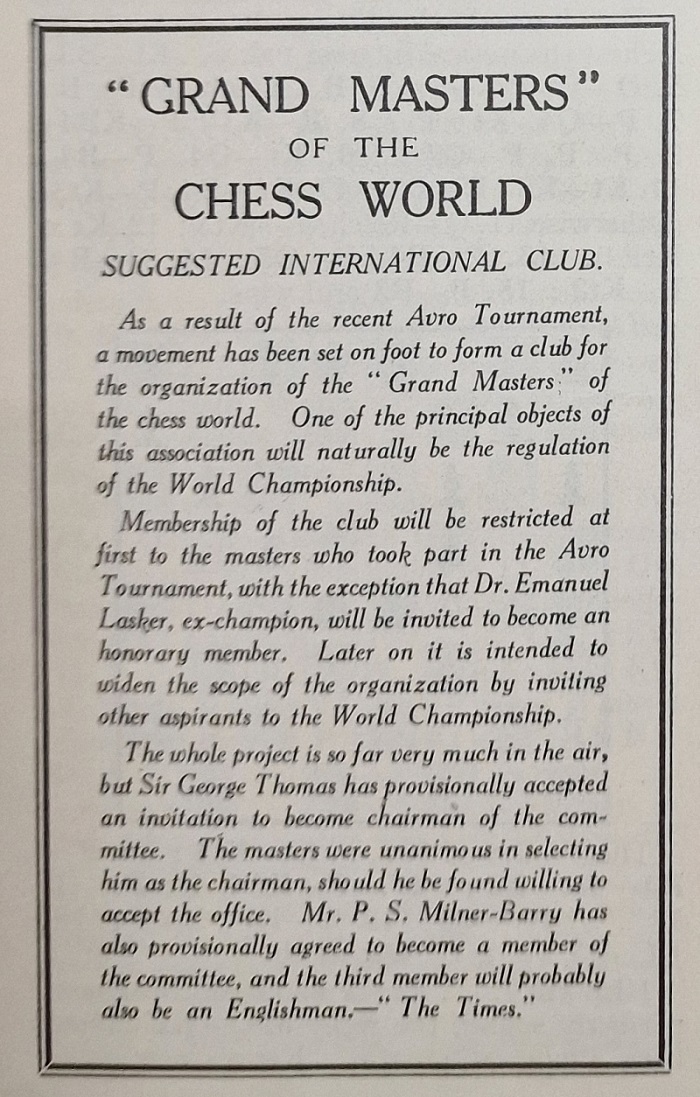

A project announced on page 8 of the (London) Times, 4 January 1939:

The report was reproduced on page 167 of the January 1939 CHESS, as mentioned in C.N. 1590:

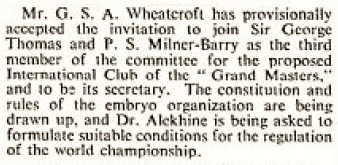

Page 8 of the 16 January 1939 edition of the Times had a brief follow-up note about the Anglocentric initiative (on which further information is sought):

(10695)

Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) writes:

‘In a letter to Ilya Maizelis (New York, 7 July 1939), Emanuel Lasker wrote:“Der Vereinigung der Schachmeister, deren Mitglieder Botwinnik, Alekhin, Capablanca, Euwe, Flohr, Fine, Reszhewski, Keres sind, bin ich nun angeschlossen und hoffe, dass sie etwas zur Förderung des Meisterschachs beitragen wird.”

Are any details known about this attempt to form a masters’ association, perhaps in conjunction with the AVRO, 1938 tournament?’

(11892)

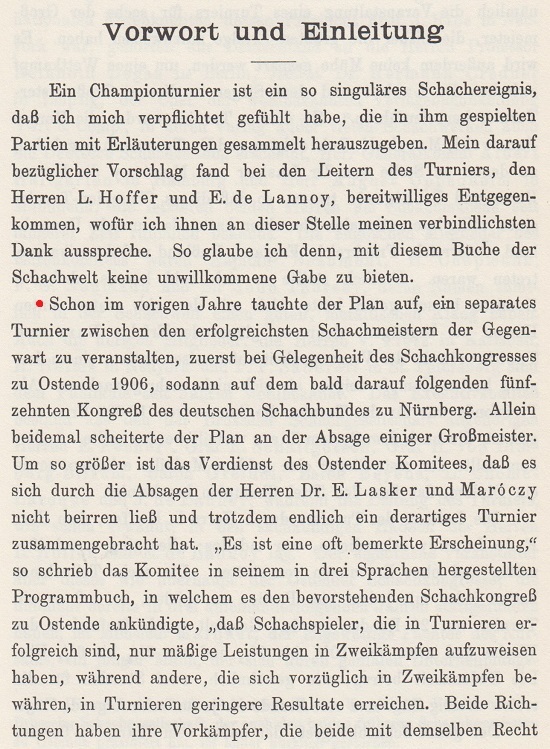

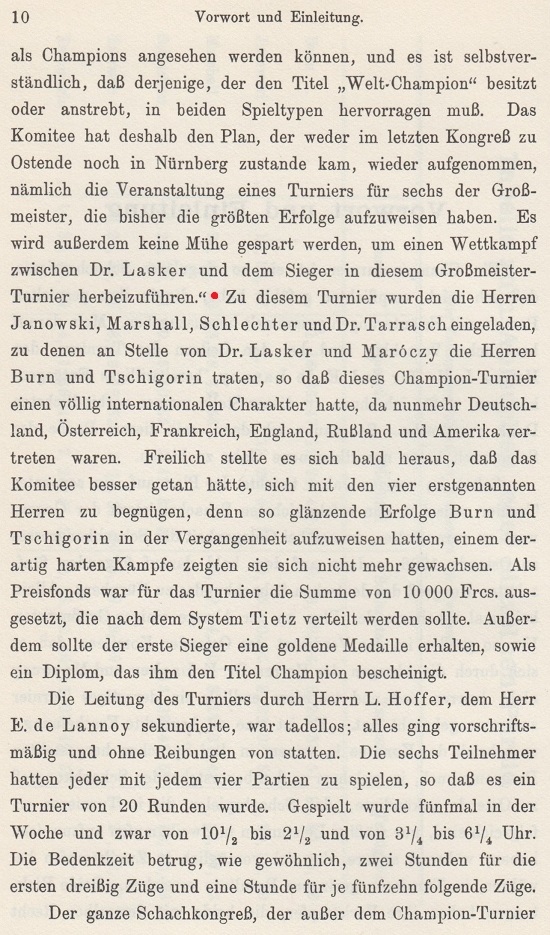

Morten Lilleøren (Oslo) notes the Großmeister references on pages 9-10 of Siegbert Tarrasch’s introduction to his Ostend, 1907 tournament book:

An immediate question is whether any reader has access to the trilingual Programmbuch.

(10904)

Among the points made on page 3 of The Guinness Book of Chess Grandmasters by William Hartston (Enfield, 1996):

This book is about the real Grandmasters.’

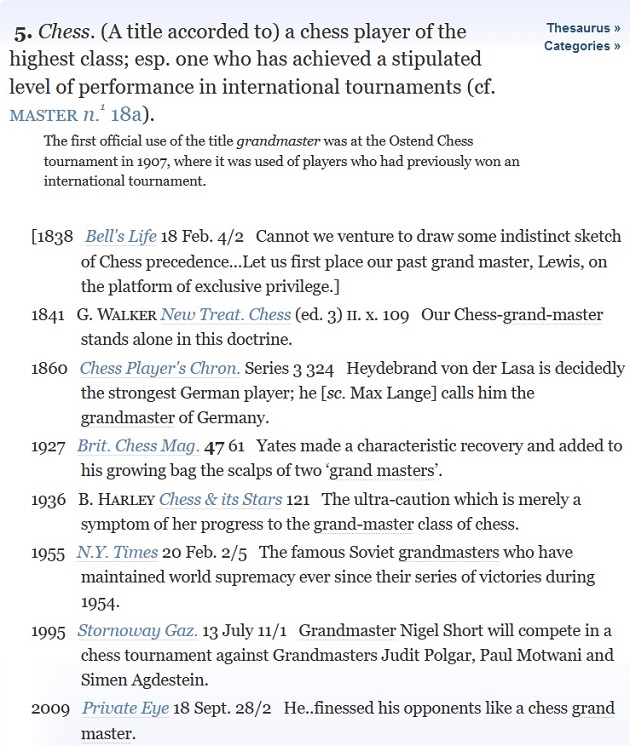

The on-line entry in the Oxford English Dictionary currently stands as follows:

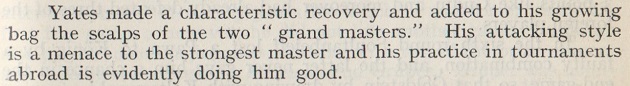

From page 61 of the February 1927 BCM:

This was in the conclusion of the report on Hastings, 1926-27, where Yates defeated Tartakower and Réti.

(11444)

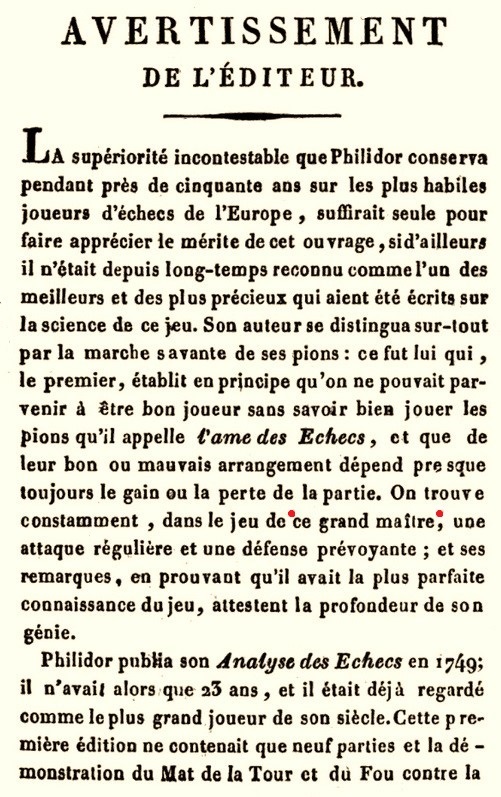

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) notes ‘ce grand maître’ with reference to Philidor on page 5 of the Philadelphia, 1821 edition of Analyse du jeu des échecs:

Commenting that ‘grand maître’ is a less distinctive term than ‘grandmaster’, since the French adjective may be translated as either ‘grand’ or ‘great’, our correspondent adds that volume 1 of Le Palamède (Paris, 1836) had the following on pages 318-319:

‘Philidor a nommé les pions l’âme des échecs, et il était particulièrement remarquable par sa manière savante de les conduire. L’école fondée en France par ce grand maître a hérité de sa science.’

(11478)

The report on FIDE’s 8th Congress (Prague, 22-26 July 1931) indicates that on behalf of the Polish Federation Dawid Przepiórka asked FIDE to draw up a list of International Masters and establish the conditions for the granting of such titles. The President, Dr Rueb, was unenthusiastic, but to study the question a small Committee was formed, with Alekhine, Vidmar, and Przepiórka among the members. It was not until the 12th Congress (Warsaw, 28-31 August 1935) that a text was adopted. This stated that the title of International Master would be awarded by FIDE to any player who won a tournament featuring a minimum of 14 players if at least 70% of the players were International Masters, or who came second twice in such events. Less successful tournament scorers could obtain the title if they also won a recognized match (of at least four games up) against an International Master. Initially, the Committee was to prepare a basic list of recipients. Titles would be awarded for life, and there could be no appeal against the Committee’s decisions.

When a (modified) system was eventually introduced (20th Congress, Paris, 20-22 July 1949), a distinction was made between Grandmaster and International Master. There were under 30 of the former, and fewer than 100 of the latter.

Most of these title-holders were familiar personalities whose names needed no adornment, but nowadays ‘Grandmaster’, ‘International Master’, etc. are used almost like forenames. Paradoxically, the very top players outgrow their titles; it would be incongruous, and perhaps even insulting, to refer to ‘Grandmaster Fischer’.

(1982)

Discussion topic: is there any good reason why master titles for playing ability should be awarded for life? We believe that, by analogy with the ‘world champion’ appellation, they should be lost if results over a fixed period (perhaps five years) are sub-standard or non-existent. This would reduce the cheapening of FIDE titles, although nothing would prevent a player from referring to himself as, for instance, a ‘former Grandmaster’.

From Sidney Bernstein (Brooklyn, NY, USA):

‘I agree with you that something should be done about the permanence of FIDE titles. The latest oddity was the GM award (practically posthumously!) to Dake. While he was once quite strong, I know of no tourney success for him, and see his GM title as part of the FIDE “old boy” structure. (Incidentally, I played him eight times in tourneys – result was, I lost one, drew seven.)’

We would point out another dubious case: in 1985 FIDE awarded Golombek an emeritus GM title. According to Elo’s book, H.G.’s best five-year rating was 2450, the same figure as that of Eugene Znosko-Borovsky, whom Golombek (on page 522 of the paperback edition of his Encyclopedia) described as ‘a minor chess-master’. It is also worth noting that on page 61 of the January 1988 FIDE Rating List (an example we take at random) Anatoly Dozorets is mentioned as the 20th strongest player in the United States, with a rating of 2495, yet without even the International Master, let alone the Grandmaster, title.

The point is that once a governing body decides to use a statistical system it must endeavour to follow it through fairly and logically. Sentimental end-of-career gestures have no place ...

(1638)

As regards titles for life, a good contribution to the debate has been made by Nigel Short in a Letter to the Editor published on page 3 of the 9 October 1988 issue of Inside Chess. To quote the essence of his proposal:

‘There can be no doubt that the Grandmaster title is not what it was meant to be: an honor awarded to only the finest players in the world. An examination of the rating list shows that far too many of these “Grandmasters” are in fact remarkably weak: 56 of them are rated below 2450, the minimum rating required to obtain the title. A further dozen or more Grandmasters are inactive altogether. Grandmaster inflation is eroding the title’s value almost by the day. Something should be done about it urgently.’

Short proposes that Grandmasters whose Elo rating drops below 2450 on two consecutive Rating Lists should revert to being International Masters, and that Grandmasters who play fewer than ten rated games in two years should also lose their titles. Such ‘former Grandmasters’ (our term) could recover their titles by making a single Grandmaster Norm, providing that they also secured the 2450 minimum rating.

Since Short’s open letter was addressed to the Grandmasters’ Association, it was not the place to discuss parallel cases where ‘International Master’ is a misnomer.

Page 3 of Inside Chess, 10 November 1988 has a playfully sarcastic reply from Andy Soltis which does not lend itself to shortening here. Perhaps a reader can phrase the counter-arguments for Chess Notes more maturely.

(1735)

Louis Blair (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) writes:

‘I think the point that Soltis is trying to make is that life is hard enough for ageing grandmasters without people trying to take their titles away. It seems to me that many think of a GM title as being analogous to a doctor’s or lawyer’s degree. Such titles represent what you have accomplished and not necessarily your current status. In my own field, for example, I have never heard of anyone losing their math Ph.D. because they no longer published. We do have ratings to indicate a person’s playing strength, although I admit that it would probably be a good idea if such lists, as a matter of routine, indicated in some way how active the player has been. Maybe there should be a provision to lower a player’s rating by some set amount (only once) if he or she has been inactive long enough. I suspect, however, that this idea would be at least as unpopular as revoking grandmaster titles.’

It should be noted that the twice-yearly International Rating List has a column for the number of games played by each master.

From Hugh Myers (Davenport, IA, USA):

‘The Elo rating system is so fundamentally inaccurate that it would be ridiculous to grant or remove GM titles based on ratings of 2450 or 2449. Elo wrote on page 18 of issue 36 of The Myers Openings Bulletin: “The term accuracy is not even properly applicable to ratings.”’

Nigel Davies makes an interesting contribution to the debate on page 19 of the March 1989 CHESS. He considers Short’s proposal ‘rather brutal’ and comments that ‘anyone losing the title by a rule which they considered to be unfair might have very few qualms about “buying” the redeeming norm’. Moreover, ‘players such as Botvinnik and Bronstein would lose their titles’. Davies proposes instead that ‘only grandmasters rated 2500 or more should be counted as such in norm calculations’, after which ‘lower-rated GMs could no longer be used in the “norm factories”’. In addition, ‘international masters should only be counted for IM norm creation when they have a rating of 2400 or more’.

(1807)

W.D. Rubinstein writes (Geelong, Australia):

‘Concerning the profligacy of grandmaster titles, I should like to suggest a new category called “World Master”, which would include (A) the current world champion and all living, previous ones; (B) anyone who has played unsuccessfully in a world title match; (C) up to ten other players of long distinction. At present, category C would possibly include: Najdorf, Szabó, Gligorić, Geller, Larsen, Portisch and perhaps two or three others. As there are either nine or ten persons in (A) and (B), depending on how to count Short/Timman, there would be only 15-20 “World Masters”, making it the equivalent of what was meant by “grandmaster” before the Second World War.’

We recall the view of W.H. Cozens, given on page 161 of the April 1976 BCM:

‘The obsession with grading is fast becoming the curse of chess; from the top (where the multiplication of grandmasters already calls for the creation of a new supermaster class – the dozen or so with legitimate pretensions to a world title match) right down to club level where it is simply laughable.’

(2010)

As far back as the May 1953 Chess Review (page 129) a reader, W.N. Wilson, had declared himself ‘perturbed about the loose use of the term “grandmaster”’. In reply the Editor remarked that ‘with a couple of dozen grandmasters around now, we ought to have a grade designated between the bulk of these and the world champion’.

(Kings, Commoners and Knaves, page 224)

From the article ‘The mating game’ by Bernard Levin on pages 171-174 of his anthology All Things Considered (London, 1988):

‘It is dangerous; too many great players have been on the edge of madness, or over it, for it to be a coincidence. The mind of a grandmaster is something that cannot be properly understood, so extraordinary is its ability; and those of the handful of what may be called the supergrandmasters defy imagination.

... I sometimes think that the real wonder of supergrandmasters is that a good many of them are perfectly sane.’

The article first appeared on page 16 of The Times, 9 November 1987.

A quote from page 43 of E. Klein and W. Winter’s The Anglo-Soviet Radio Chess Match (London, 1947), the writer of the passage being Klein:

‘To my mind the days of a small super class like Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine are gone for ever: these men were inventors. Now masters are merely technicians of varying skill and the question of the world title, which it would seem is causing some heart-burning, is really out of date.’

(2293)

P.W. Sergeant wrote a general historical article about the use of titles on pages 72-73 of the third issue of Chess Pie (1936).

Below is an extract from an editorial on page 169 of the June 1946 BCM:

‘Of late years a new custom has crept into chess life, a custom which is not altogether desirable, if we look upon chess as an art.

We refer to the custom of giving chessplayers various and rather high-sounding titles. For the best part of a century we were satisfied with the denominations of amateurs and masters, the master being either a front rank professional or an amateur able to hold his own in the best company. Comparatively recently we have heard of candidates for mastership, masters and grandmasters.

In art there is really no call for titles. The artist himself creates his own title by the lustre his achievements give to his name, and nobody will contend that the title “Grandmaster” is an adornment to the name of Botvinnik. It is rather the other way about. We are becoming blinded to the absurdity of it all, but it would become clear to many if they tried to say “Grandmaster Morphy”.’

On page 202 of the July 1955 Chess Review Ossip Bernstein wrote, after referring to the ‘grandmaster tourney at St Petersburg’ in 1895-96:

‘The title Grandmaster was as yet unknown, but the idea was widely understood. The title, Grandmaster, was introduced in the international tourney at Ostend in 1907, in which I shared first prize with Akiba Rubinstein. I should have contested a match for this title – but the match never took place.’

(A Chess Omnibus, page 178)

On pages 297-298 of the October 1968 BCM D.J. Morgan noted Bernstein’s remark about Ostend, 1907 (see above) and added:

‘The following note comes to us via the Illinois Chess Bulletin, May 1968. George Tiers, the editor of the Minnesota Chess Journal, has found this reference in the chess column of the Winona Republican of 8 September 1858 to “our ancient ‘Chess Grandmaster’ Philidor”. Furthermore, George Walker, in his New Treatise of 1841 (page 109) wrote of the famous Frenchman as “our Chess-grandmaster”.’

‘What is a chess master player? What is the difference between a “master” and a “grand master”? About what date may we anticipate the advent of the “great grand master”? These are the conundrums of the moment for the amusement of any detached spectator of the chess world.

Time was when there were no masters. There were plenty of woodshifters (as now), and a few good players of varying strengths (as now). But this must have been in a pre-historic era; even As-Suli has a boast about his mastership. Having invented the stupid term “master” (thrice stupid – untrue, unnecessary, unholy in its commercialism) the few good players temporarily basked in a complacent glow of superiority.

Unhappy men! Fools! Were they permitted to enjoy their superiority undisturbed? Not on your life! By this path, and that snicket, and yonder ginnel, crept woodshifter after woodshifter into the sacred circle. With no precise definitions, interpreted by Babel in as many ways as the tongues of Europe, a flood of mediocrity has swamped the realm of “masters” thoroughly and efficiently as commercialism must ever swamp mere merit.

The few good players of the age have realized that “master” is a ruined term. In self-defence someone has invented “grand master” as a new mark. Futile endeavour – at the present rate of production of “grand masters” it is a calculable distance to their successors, the “great grands”.

Is there not here, again, work for the FIDE?’

The above is an article by ‘Theta’ on page 129 of the Chess Amateur, February 1926.

(3780)

‘All agree the grandmaster title suffers from inflation and so has lost much of its value. The FIDE awards the title too readily and on conditions known in advance. So agreements are made in the corridors: “Help me and I will help you ...” The practice is irregular and needs correction.’

Criticism of ‘grandmaster inflation’ is frequent, but the above passage was written 44 years ago. The author was Petar Trifunović, on page 202 of Chess Review, July 1965.

(6238)

As quoted in C.N. 6764, in Chess Life, December 1968 Larsen commented as follows when asked, on page 437, whether he thought that the grandmaster title had been cheapened by the standards which FIDE set:

‘In the last ten years, yes. Many so-called grandmasters are not worthy of the title.’

Larsen added:

‘I understand that Robert Byrne is proposing a scheme to make the title really first-rate, difficult to obtain without real grandmaster performance and consistent evidence of it in international tournaments.’

From page 484 of the December 1972 BCM (in an article by R.W.B. Clarke):

‘It may be worth listing the top 14 – the greatgrandmasters of 2600 up (BCF 250).’

The 1952 article by Euwe mentioned in C.N. 10276 (pages 74-75 of Chess Review, March 1952) began with this observation:

‘The USSR Championship usually enlists the efforts of almost half the holders of the title of Grand Master in the FIDE.’

From page 296 of CHESS, June 1968:

(10279)

An observation by W.A. Fairhurst on page 134 of the April 1955 BCM:

‘Many players will agree that there are too many international masters and far too many so-called grandmasters. Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine could be considered of such high rank amongst the masters of the past that they were entitled to such a distinction as grandmaster, but it is doubtful if there is a single player living at present worthy of this title. Botvinnik, Keres, Smyslov and Reshevsky are all fine players but they have not that superiority over some of the other leading masters which entitles them to be described as “grand”. In addition to these four there are apparently 37 other grandmasters, and this makes the distinction almost meaningless.’

(10999)

C.N. 1638 pointed out that in 1985 FIDE made Harry Golombek an emeritus GM. However, H.G. evidently considered that to be mere rubber-stamping:

‘Known as the Rubinstein Variation after the great Russo-Jewish master, Rubinstein, this line was all the rage when I was a young grandmaster ...’

Source: Beginning Chess by H. Golombek (Harmondsworth, 1981), page 146.

(1808)

In his Independent obituary of Harry Golombek referred to in C.N. 11557, William Hartston wrote:

‘He was awarded the title of International Grandmaster in 1985, which he liked to stress was not an honorary award, but a belated recognition of his playing achievements in the 1940s.’

Confusion sometimes arises over the status and terminology of such a title. In keeping with Jeremy Gaige’s usage in Chess Personalia, C.N.s 1638 and 1808 stated that in 1985 FIDE made Harry Golombek an emeritus GM, but in addition to ‘emeritus’ and ‘honorary’ another possibility is ‘honoris causa’.

Page 121 of FIDE Golden book 1924-2016 by Willy Iclicki gave a single list, without different categories, of individuals awarded the grandmaster title in 1985. Golombek appeared, with the forename ‘Garry’.

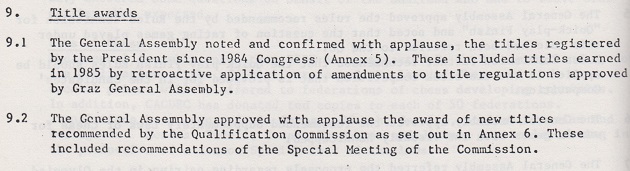

Some particulars are shown below from FIDE Congress, Graz 1985 Minutes & Annexes, beginning with an extract from page 4 of the minutes of the General Assembly (29-31 August):

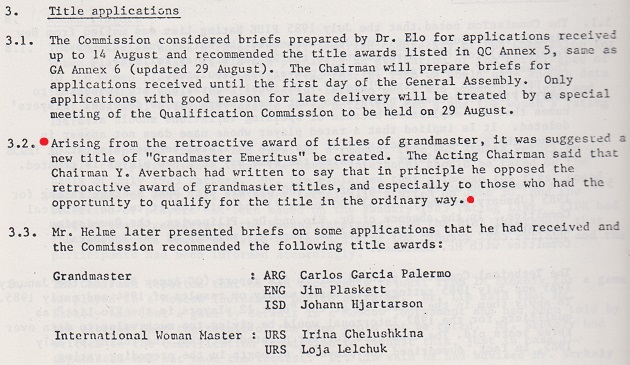

The FIDE document included a report on the meeting on 25-26 August of the Qualification Commission, whose Acting Chairman was Eero Helme (Finland):

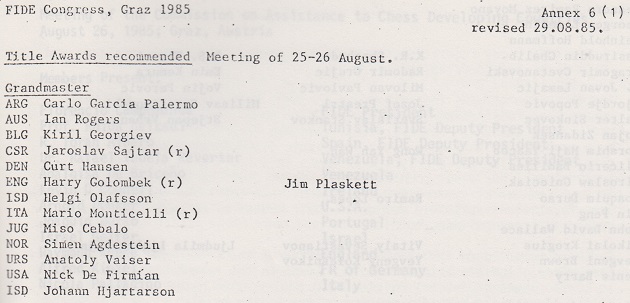

The relevant part of the above-mentioned list:

The documentation leaves a number of loose ends, and we shall welcome authoritative guidance on this topic, and not only concerning the particular case of Golombek.

(11558)

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) reports that page 54 of issues 13-14 of Leaves of Chess quoted the following from the New York Times, 22 March 1959:

‘Svetozar Gligorić, one of the eight candidates for the honors by virtue of his No. 2 finish in the interzonal matches at Portorož, and Dr Petar Trifunović, also a grandmother, narrowly escaped death in an automobile mishap.’

(4540)

The following article by the Badmaster, G.H. Diggle (1902-93), was originally published in the January 1986 Newsflash – see also page 34 of volume two of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1987):

‘Since the Government’s rejection of the Church of England’s report on the state of the nation, “rubbishing” is all the rage. The irascible BM, determined to be “with it”, glowered through the December Newsflash (which arrived by the same post as his Electricity Bill) to see what he could “rubbish”. He had to go no further than the Editorial, which exhorts us all (after our Silver Olympiad and Bronze World Test Medals) to “sit back over Christmas and enjoy it, if you remember the days of no Grandmasters”.

The BM, a confirmed Chess Luddite, as cheerful at Christmas as Gabriel Grub, not only remembers, but glories in, the days of no British Grandmasters, and indeed no Grandmasters at all. Capablanca was known as Capablanca, and not belittled by having ponderous prefixes tacked on to his illustrious name, or by every masterpiece he produced being dubbed “a true grandmaster game”. And Reshevsky was Reshevsky, though there was one commentator who used to croon about him in this manner: “See, Sammy’s king arrives just in time. What a master of technique is Sammy! Now the stage is set. Soon the rook’s pawn will advance. A grandmaster ending indeed. Is he not a rare technician?”

Slowly but surely during the last 50 years, Grading, Grandmasters and now the invasion of huge weekend Tournaments over our land have ruined the English Chess Countryside, where players like the BM once enjoyed immense and undisturbed rustic renown (ensured by standing drinks from time to time to the Editor of the local rag). When the BM won the Lincolnshire Championship (at the fifth attempt) such was his repute amongst his townsmen (population 4,000) that he actually gave a “simul” as a sideshow at a charitable fête. Fourteen “victims” offered themselves for slaughter – equally surprisingly, 14 chess sets were raked up too – some of them not very favourable to the development of the Champion’s powers, being great red and white “Bone-Henges” with the fatter pieces bulging against each other like overhanging Elizabethan houses in a narrow street. Even then, by a superhuman effort, he scored +10 –2 =2 in three hours and can give excellent reasons for his two defeats – in one case, he never recovered after losing four pieces in two moves, discovering too late (and chivalrously keeping quiet about it) that his opponent (a most estimable lady music teacher) was quite innocently playing too many crotchets in a bar – in short, moving when the maestro arrived and again when he departed.

But today Arcadia is not left to enjoy its chess in its own way. We must all try to be Grandmasters, though (as chess officialdom admits) there are already too many of them, and if one of them is pointed out in the street no-one turns round to look. Their deportment, indeed, is often deplorable – the other day one of them actually won a Tournament playing horizontally, and crawling about the arena like the Serpent in the Garden. Staunton and Löwenthal would have fainted away at the sight. Let the BM’s message for 1986 be: “Grandmasters must go! Long Live Bad Chess, and Up the Chess Proletariat!”’

(5369)

From C.N. 5467, below is an extract from an article by G.H. Diggle in the May 1976 issue of Newsflash which was reproduced on page 11 of his anthology Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘There are recent signs, however, that amongst other modern horrors, the constant use of “Grandmaster” as a stopgap adjective is on its way out. This may be due partly to the age of galloping “Grandmaster” inflation that we now live in, and partly to the influence of Bobby Fischer, one of whose minor achievements has been to restore a few one or two syllable words to chess annotation, and to clear away much adjectival dead wood.’

G.H. Diggle, the Chess Badmaster had the following remarks by him, from C.N. 2896:

‘Had “grandmasters” been invented in those days, they would have qualified for that elephantine title only by having been dead for at least 25 years, or by having successfully evaded all challenges after negotiations dragged out for a similar period. Morphy finally disposed of this cult, and it was at long last realized by writers like Walker that a champion had arisen who might possibly be superior to Philidor.’

The above-mentioned feature article also quotes, from G.H. Diggle’s letter to us of 4 March 1987, a remark about David Spanier’s chess column in the Daily Telegraph:

‘The other day he used the expression “grandmasterly”, which upset me for the rest of the day.’

Also pointing out the adjective ‘grandmasterly’ in a chess report by Malcolm Pein on page 13 of the Daily Telegraph, 13 August 1988, G.H. Diggle informed us on 2 September 1988:

‘Constant repetitions of the players’ titles almost occupy the space of a paragraph.’

The report refers to:

‘Grandmaster Jonathan Mestel’, ‘international master William Watson’, ‘grandmaster Glenn Flear’, ‘international master Julian Hodgson’, ‘international master Tony Kosten’, ‘grandmaster Niaz Murshed’, ‘grandmaster Murray Chandler’, ‘international Robert Belling [sic]’, ‘international master Michael Adams’, ‘grandmaster Ian Rogers’, and ‘female international master Christine Flear’.

C.N. 6625 quoted G.H. Diggle’s words from page 4 of the January 1981 BCM:

‘Staunton, though he had his faults, would have cut his throat before penning the hideous expression “grandmaster norm”. He would have seen at once that the second word reduced the glory of the first to a meaningless nothing.’

A remark by G.H. Diggle from an article in the December 1981 Newsflash which was reproduced on page 78 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘... to imagine that “psychological motifs” and whatnot are the exclusive monopoly of grandmasters is to fall into the snobbish fallacy of the Sergeant Major who (when a poor Private reported sick with a “pain in the abdomen”) roared at him: “You ’ave a stummick! Only orficers has abdomens!’

(7805)

One of T.H. Tylor’s very rare forays into chess writing was ‘The Grand Masters’ on pages 26-29 of the anthology Home and Away (London, 1948). Directed at a mainstream audience, the article contained little that is quotable, although on page 28 he described Alekhine as ‘perhaps the greatest chess genius of them all’.

(5966)

Jens Kristiansen (Qaqortoq, Greenland) is trying to ascertain the highest age at which anyone has gained the grandmaster title for over-the-board play in regular fashion (and not, for instance, honoris causa).

(6146)

Brian Karen (Levittown, NY, USA) writes:

‘Has there ever been a grandmaster who had a parent who was a grandmaster?’

(6340)

Which chess book contains the most hype? One promising contender (at least from the pre-Cardoza era) is Fred Reinfeld’s Beginner’s Guide to Winning Chess, which was first published in 1964, the year he died. Here is the back-cover of the 1994/2006 paperback edition from Foulsham (which used the spelling Beginners’):

There is plenty more inside concerning ‘the rarest of Grandmasters’.

(6585)

In a report on the 11th Capablanca Memorial Tournament in Camagüey on page 196 of the April 1974 CHESS David Levy stated that Guillermo García ...

‘... had the satisfaction ... of beating three grand masters and he left no doubt that he will be Cuba’s first GM.’

That occasioned a reaction on page 79 of the December 1974 CHESS:

The prediction about Guillermo García proved wrong (he became a grandmaster in 1976, the year after Silvino García), but the matter came back to mind when we saw page 9 of the 8/2013 New in Chess. A reader, John DiLucci of Irving, TX, USA, condemned the statement (‘so ridiculous that it is beyond comprehension’) from page 36 of the 6/2013 issue that ‘in 1975 Cuba’s first grandmaster Silvino García dedicated his title to Che’. Mr DiLucci wondered whether the author of the offending article on Che Guevara (Adam Feinstein) and the New in Chess editorial staff could be ‘so uneducated ’ as to be unaware of Capablanca.

The letter was deemed easy to rebut and, therefore, printworthy, and in the 8/2013 New in Chess about 40 lines were made available for the ‘discussion’, which included the editorial response that Capablanca was never ‘officially’ a grandmaster, given that he died some years before FIDE introduced the title (a perfectly defensible argument).

In fact, though, Mr DiLucci had merely been reacting to a pull-out quote in the 6/2013 issue, and neither he nor the editorial staff apparently realized that on the previous page of Adam Feinstein’s article (i.e. page 35) Capablanca was specifically mentioned:

‘... Silvino García, who in 1975 had fulfilled Guevara’s prophesy [sic] by becoming Cuba’s first grandmaster since the death of Capablanca in 1942.’

(8433)

Mark Hoffman (Leipsic, OH, USA) asks whether it is possible to name about half-a-dozen players who gained the grandmaster title for over-the-board play at a relatively advanced age. Moreover, from such a list can it be determined who achieved the title the fastest and from the lowest starting-point in terms of playing strength?

(8467)

Paul Dorion (Montreal, Canada) notes two players who achieved the grandmaster title in their mid-40s: Vasja Pirc (born 1907) in 1953, and Albéric O’Kelly de Galway (born 1911) in 1956.

(8472)

From Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel):

‘Several players received the grandmaster title when in their 50s, including Julio Bolbochán (born 1920) in 1977 and Gösta Stoltz (born 1904) in 1954. Slightly younger title-holders: Isaac Kashdan (born 1905) became a grandmaster in 1954 and Raúl Sanguineti (born 1933) in 1982. Carlos Torre (born 1904 or 1905) was awarded the title in 1977, over half a century after almost completely retiring from competitive chess.

Not included on this list are honorary title-holders such as George Koltanowski, Esteban Canal, Erik Lundin and Vladas Mikėnas, who were granted the title when in their 80s or late 70s. Similarly, the group of veteran players Jacques Mieses, Géza Maróczy, Akiba Rubinstein, Ossip Bernstein, Oldřich Důras, Milan Vidmar, Boris Kostić, Savielly Tartakower, Grigory Levenfish, Ernst Grünfeld and Friedrich Sämisch, who were awarded the grandmaster title en bloc by FIDE in 1950 in recognition of their past achievements. Another old-timer, Efim Bogoljubow, who belonged to the same group of players, received the title the following year, the delay being for political reasons.’

After the general topic of the ‘oldest grandmaster’ was raised in C.N. 6146, Andrew Bull (Cheltenham, England) referred in C.N. 6155 to Tim Krabbé’s ‘Open Chess Diary’ (item 193), where it was noted that Jānis Klovāns (born 1935) became a grandmaster in 1997 by winning the world senior championship. Mr Bull added the case of Valery Grechihin (born 1937), who gained the title in 1998, and he now mentions Leif Øgaard (born 1952) in 2007 and Mark Tseitlin (born 1943) in 1997, as well as world senior champions (e.g. Yuri Shabanov, Larry Kaufman and Vladimir Okhotnik) who, by winning that championship, received the grandmaster title when over 60.

(8477)

Morten Fabrin (Viborg, Denmark) adds that Jens Kristiansen (born 1952) became a grandmaster by winning the World Senior Championship in 2012.

From page 266 of the Complete Book of Beginning Chess by Raymond Keene (New York, 2003):

‘The most renowned chess grandmaster in Baghdad was As-Suli (880-946 AD).’

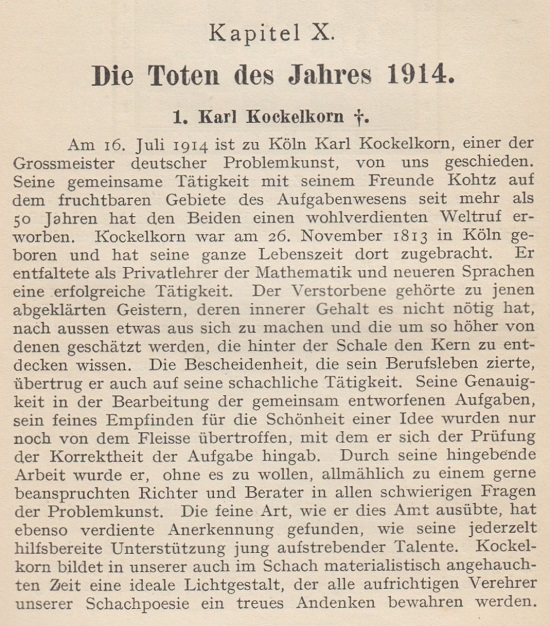

An unusual instance of the term ‘Grandmaster’ to describe a problemist occurs at the start of the obituary of Karl Kockelkorn on page 248 of Schachjahrbuch 1914 II. Teil by Ludwig Bachmann (Ansbach, 1914):

(11010)

From from the obituary of John Wisker on page 88 of La Stratégie, 15 March 1884:

‘Sans être un grand maître, ou du moins sanctionné tel, puisqu’il n’avait pris part à aucun tournoi international, M. Wisker était de première force; en 1870 il était champion de l’Angleterre et sa renommée serait devenue universelle s’il n’avait dû quitter la Métropole pour l’Australie.’

Pages 121-122 of the August 1872 Chess Player’s Chronicle praised Wisker (‘depth, soundness and brilliancy are all characteristics of his play’) when noting his victories in the British Chess Association’s Challenge Cup (‘England’s champion chessplayer’) in 1870 and 1872.

John Wisker (page 353 of the August 1893 Chess Monthly)

An excerpt from page 113 of Kings of Chess by William Winter (London, 1954), in the chapter on Alekhine:

The ‘I am not Grand Master’ remark was discussed in C.N. 5525.

(11419)

Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) adds a reference to Samuel Loyd on the subject of chess grandmasters:

‘We present this week a choice chess-nut from the hands of the problem grand master, Mr Samuel Loyd.’

Source: Philadelphia Times, 7 March 1880, page 2.

(12102)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.