Edward Winter

Joop Elderhorst (Rotterdam, the Netherlands) raises the subject of chess masters’ final resting places.

Below are two photographs of Capablanca’s grave in the Colón Cemetery, Havana. They were taken by Bernardo Alonso García (who owns the copyright) and sent to us in 1994, with his permission, by Armando Alonso Lorenzo (Prov. Ciego de Avila, Cuba).

(3811)

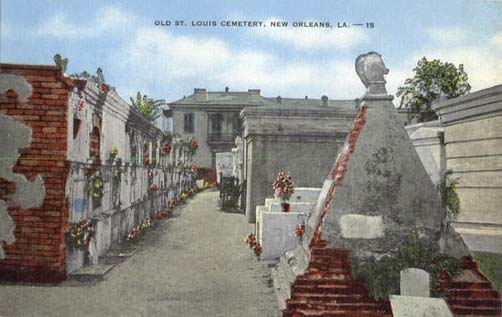

Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) has sent us this postcard:

Caption on the reverse side: ‘The most interesting of New Orleans’ historic burial places, the St Louis Cemetery No. 1 – there are three – has been in use for 175 years, with some of the inscriptions still decipherable dated 1800. Here lie the bodies of Paul Morphy, the famous chessplayer; Gayarre, the historian; Etienne de Boré, who first made granulated sugar; Charles LaSalle, brother of the famous explorer.’

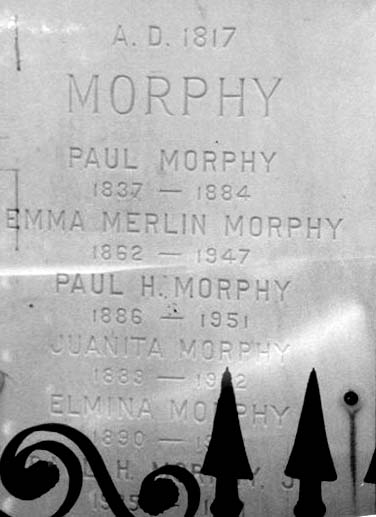

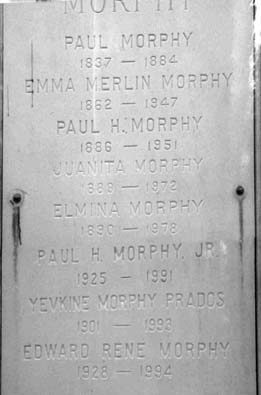

We have received from Gordon W. Gribble (Hanover, NH, USA) a number of photographs taken by him in New Orleans in August 2002, including the following of Paul Morphy’s tomb:

(3849)

See also the photograph on page 161 of the June 1950 Chess Review.

Marek Lada (Warsaw) sends us a photograph which he took in August 2005 of Adolf Anderssen’s grave at the Osobowicki Cemetery in Wrocław:

(3908)

Below is the report by ‘J.A.S.’ (Jakob Adolf Seitz) on page 220 of CHESS, 28 April 1956:

‘In memory of the tenth anniversary of the death of the late world champion Alexander Alekhine, several hundred people – more than one would have expected on an icy cold day – gathered outside the main entrance to Paris’s famous Montparnasse cemetery, just before eleven in the morning of 25 March 1956.

Folke Rogard, President of the International Chess Federation, was one of the first to arrive. Soon there came a strong delegation from the USSR led by grandmaster Ragozin. Some unkind tongues suggested that the Russian chessplayers were the main attraction of the ceremony to many locals; and certainly Smyslov, Keres, Bronstein, Geller, Petrosian and others were energetically pestered for autographs.

At 11 a.m., which was said to have been the hour of Alekhine’s death, the crowd moved to the monument.

We found that Abraham Baratz, a gifted sculptor, many times chess champion of Paris in his younger days, had chiselled a statue of Alekhine in his youth sitting at a chess board. All in white marble; and it was to be noted that his chessmen were not Staunton, but French, in type.

The base of the tumulus was a huge chessboard itself, though few noticed it at the time, so completely was it covered by wreaths, of which the Soviet delegation’s was the biggest. Beneath the sculpture appeared first Alekhine’s name in his native Russian characters, then the inscription “Alexandre Alekhine, génie des échecs de Russie et de France, 1 novembre 1891 – 25 mars 1946” and below “Grace Alekhine née Wishar 1876-1956”.

On the socle of the tumulus was an announcement that the monument had been erected on 25 March 1956 by the International Chess Federation. The names of Rogard (Sweden), Ragozin, Berman (France), Botvinnik (who was not present), Count dal Verme (Italy) and others followed.

Among French chessplayers present were Dr Bernstein, C. Boutteville (present French champion), Biscay, Halberstadt, Mme Chaudé de Silans, Muffang, Ségal and others. Edmond Lancel had come from Brussels. Rogard gave a brief address in French, Ragozin another in officially translated Russian. Alekhine’s son responded, followed by Mme Isnard, a daughter of Alekhine’s last wife. The chessplayers then repaired to a famous restaurant, where a hundred anecdotes about Alekhine were exchanged. Not one word about this impressive ceremony did I find in any of the French newspapers – a sad commentary on the place of chess in France today.’

Confusion with the dates may be noted. Firstly, the date on the tombstone was ‘1 November 1892’, not 1891 (although the correct date of Alekhine’s birth is 31 October 1892). The ‘1891’ was apparently Seitz’s error and not a misprint by CHESS, because it also occurred in a similar report by Seitz on page 83 of the April 1956 Schweizerische Schachzeitung. The latter magazine, moreover, quoted Alekhine’s death-date on the tombstone as ‘25 March 1956’, instead of 25 March 1946, although the latter too was wrong. As chronicled in C.N. 3086, Alekhine was found dead in the Hotel do Parque, Estoril on the morning of 24 March 1946.

(4043)

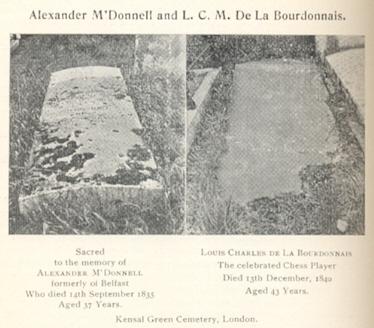

C.N. 3398 referred to the graves of McDonnell and Labourdonnais at Kensal Green Cemetery, London. Here we add that the only photographs known to us were published on page 202 of “Our Folder” (The Good Companion Chess Problem Club) 1 May 1921:

(4070)

José Angulo (Barcelona, Spain) asks about the graves of Lasker and Euwe.

With regard to Euwe, we are hopeful that a Dutch reader can provide full particulars. Concerning Lasker we have no photograph but can outline the facts.

Emanuel Lasker died at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York shortly before midday on 11 January 1941 (the erroneous date 13 January is sometimes seen even today); he had been in the hospital for two weeks. This information comes from page 1 of the January-February 1941 American Chess Bulletin, which also reported:

‘Many sorrowing friends and admirers gathered on Monday, 13 January at the Riverside Memorial Chapel, to attend the funeral services conducted by the Rev. Dr David de Sola Pool, rabbi of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, Shearith Island, a personal friend of Dr Lasker’s and a member of his chess class. That afternoon, interment took place at the Shearith Israel Cemetery in Cypress Hills on Long Island.’

Emanuel Lasker

(4103)

Johan Hut (Baarn, the Netherlands) and Pascal Losekoot (Soest, the Netherlands) report that pages 5-6 of the January 1982 Schakend Nederland stated that Max Euwe was cremated on 1 December 1981 in Driehuis-Westerveld, following a ceremony attended by hundreds of visitors and at least ten speakers. The Dutch magazine made no mention of a permanent memorial.

Our correspondents add, however, that on 7 May 2004 a statue was unveiled on the Max Euweplein in Amsterdam, near the Leidseplein. It was a bronze bust of Euwe, 65 centimetres high, and was created by José Fijnaut of Geverik (Limburg). The unveiling ceremony was performed by a city councillor, Euwe’s daughters and his grand-daughter, Esmé Lammers. (It may be recalled from C.N. 3276 that she is the writer/director of the chess story Lang leve de koningin.) [See also C.N. 4121.]

(4116)

Page 75 of Rudolf Spielmann Portrait des Schachmeisters in Texten und Partien by M. Ehn (Koblenz, 1996) has a photograph of Spielmann’s grave in Stockholm.

(4128)

Below is the early part of an article by John Keeble about Zukertort on pages 401-403 of the October 1927 BCM:

‘His ashes remain in our keeping, as he died in London on 20 June 1888 and was buried in Brompton Cemetery, to the west of the Chapel, and about half-way between it and the Chelsea Football Ground. The grave is officially known as A.F. 107 x 18. A memorial slab, known as a marble “ledger”, is laid on the grave, and bears the following inscription:

“In Memory of J.H. Zukertort, the Chess Master,

Born September 7th, 1842. Died June 20th, 1888.”The slab is in good condition and the lettering still clear, but it has sunk into the ground considerably and wants restoration in that respect.’

We also quote a passage about Harold Lommer from page 12 of Cabbage Heads and Chess Kings by Bruce Hayden (London, 1960):

‘Zukertort became his hero. So, when Harold learned that it was in London he died – he was carried from Simpson’s Divan to Charing Cross Hospital near by – Harold searched the big city for his grave.

He found it, neglected and overgrown with weeds, in a cemetery in Kensington, a genteel quarter. Shocked, he spent two afternoons in clearing and trimming the plot, and since then a fine afternoon is likely to make Harold feel restive. Before long, he is on his way to Kensington with his gardening outfit to keep the grave of the great man in shape. His task done, Harold will sit around in the sun for a while with his pocket set, and some of his best conceptions have come during these moments.’

There is a photograph of the Zukertort plot on page 170 of Der Großmeister aus Lublin by Cezary W. Domański and Tomasz Lissowski (Berlin, 2005) with the caption, ‘Reste der Grabstätte Zukertorts auf dem Friedhof “Brompton” in London (1997)’.

(4200)

The text by Hayden about Harold Lommer originally appeared on page 107 of Chess Review, April 1951.

See also the article ‘Starry, Starry Knights’ by Stuart Conquest on pages 30-32 of the October 2011 CHESS.

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘There are two documents at the National Archives regarding Zukertort’s burial in Brompton Cemetery.

In the burial register (WORK 97/165), entry no. 141702 relates to the burial of Johann Hermann Zukertort on 26 June 1888, performed by Rev. A. Veysey. Charing Cross Hospital is stated as the place of his death, and his age is given as 46 years. It was a “Common Grave” at the depth of five feet, the deceased having been removed from the parish of St Martin in the Fields, Westminster.

The records of Brompton Cemetery also contain “Burial Books”, which include copies of the bills issued. In Burial Book No. 471 (WORK 97/679), entry no. 139748 cross-refers to the above entry no. 141702 in the burial register. The time was one o’clock on Tuesday, 26 June 1888. The name of the deceased, age, and place of death are the same. The undertaker was G.T. Poole, St. Martin’s Lane. The charge was £1 16s. for “Common Interment in Grave”. On the facing page has been added:“The Parish of St Martin in the Fields

G.T. Poole.”This appears to mean that the expense was met by the parish of St Martin in the Fields (into which Charing Cross Hospital fell).’

(8616)

A 1966 photograph of Charousek’s resting place in Nagytétény, with a new tombstone and J. Hajtun, A. Földeák, R. Sallay, A. Vajda and G. Barcza in attendance, was published on the final page of volume three of Magyar Sakktörténet by Barcza and Földeák (Budapest, 1989). See also page 229 of Chess Comet Charousek by Victor A. Charuchin (Unterhaching, 1997).

(4214)

Rob Bijpost (Middenmeer, the Netherlands) informs us that the Dutch chess collectors’ society Motiefgroep Schaken is searching for graves with a chess motif:

‘So far, we have found 30 specimens of well-identified graves, such as those of Alekhine, Nimzowitsch, Staunton, Steinitz and Tarrasch, but we are particularly interested in elegant chess motiis, and not only the graves of well-known players.’

(4216)

Walter B. Hart (Burra Creek, Australia) writes:

‘Pillsbury’s gravestone (in four-sided obelisk form) can be viewed at the ‘Find A Grave’ website. Only two sides are visible in the photograph supplied, with one side inscribed Harry N. Pillsbury 1872-1906 and the other with three names and dates which seem to read: Edwin B. Pillsbury 1860?-1941; his wife M. Eva 1865?-1937; and May F. Pillsbury 1870-1941.’

(4247)

Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) has sent us a photograph taken by him of the Nimzowitsch-Enevoldsen ‘double grave’ in Copenhagen:

(4307)

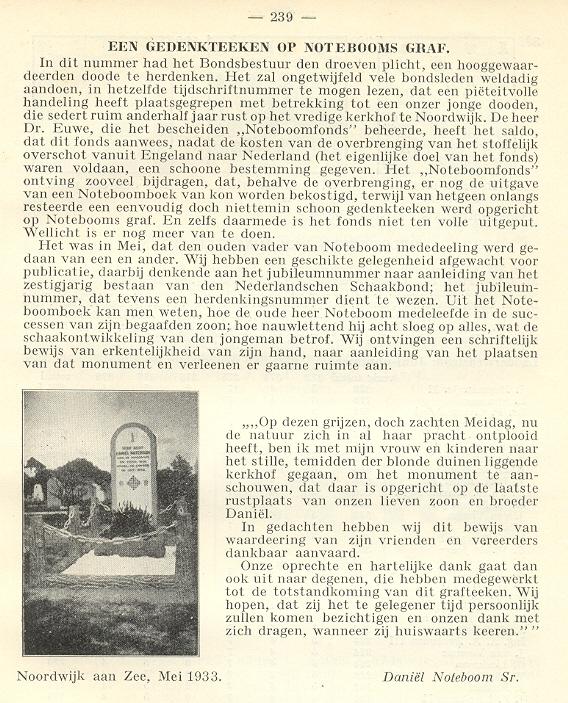

Rob Bijpost (Middenmeer, the Netherlands) sends us a photograph taken by him of Daniël Noteboom’s grave in the public cemetery in Noordwijk:

We recall in this connection the following item on page 239 of the August-September 1933 Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond:

(4352)

We have received from Jan Koppenaal (Noordwijk, the Netherlands), who was President of the Daniël Noteboom Chess Club from 1972 to 1997, a photograph of the funeral ceremony in 1932, with Max Euwe among the mourners.

(6846)

Addition on 20 July 2023:

Marieke Koppenaal (Nieuwer Ter Aa, the Netherlands) writes:

‘I went to the cemetery in Noordwijk a few weeks ago to visit the grave of Jan Koppenaal, the brother of my grandfather. He was involved in the Daniël Noteboom Chess Club for more than 40 years and was its Chairman for over 25 years. It took him ten years to have the grave of Daniël Noteboom recognized as a monument, and the little blue sign reflects that status. It means that the grave will stay and will be maintained by the local authority.’

From Norman Pillsbury (Atascadero, CA, USA):

‘I can shed a little light on the inscriptions, based on the 1898 book The Pillsbury Family by David B. Pilsbury and Emily A. Getchell. Page 162 gives the following information:

“Luther B. (Caleb, Caleb), b. 23 Nov. 1832; m. 14 Aug 1863, Mary A. Leath, of Lynnfield, Mass., who d. in Somerville, 20 Nov. 1888, aged 50. Children:

i. Edwin B., b. in Hopkinton, N.H., 30 Aug. 1866

ii. Ernest D., b. in Hopkinton, N.H., 19 May 1868

iii. May F., b. in Bridgewater, 15 May 1870

iv. Harry N., b. in Somerville, 5 Dec. 1872.”’

(4380)

Rob Bijpost writes:

‘The Dutch chess collectors’ group “Motiefgroep Schaken” has issued a 44-page booklet in Dutch with information on about 44 chess graves and illustrated with 39 photographs.

One of the pictures shows the resting-place of the Dutch chessplayer Jacques Davidson, which has a problem engraved on it. It is mate in one. The solution is Kc9 or Kd9; the king goes to heaven, and his rival is mated.

We use the term “chess grave” for any chess-related text or image, so they are not necessarily all graves of famous chessplayers. There must be more chess graves still to be traced, and we should be interested to hear from anyone with information to offer.

A small number of copies of the booklet are still available in case any readers of Chess Notes inform you of their interest in acquiring one.’

(4452)

Tomasz Lissowski (Warsaw) submits two photographs which he took at the Jewish Cemetery, Okopowa str., Warsaw. He reports that there are three graves of Winawer family members: Szymon (shown on the left), his wife, Adela née Kerner (on the right) and their son, Rafał.

(4499)

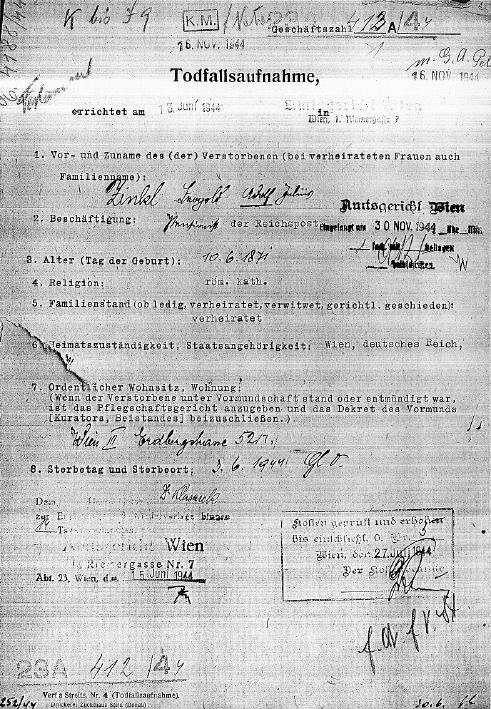

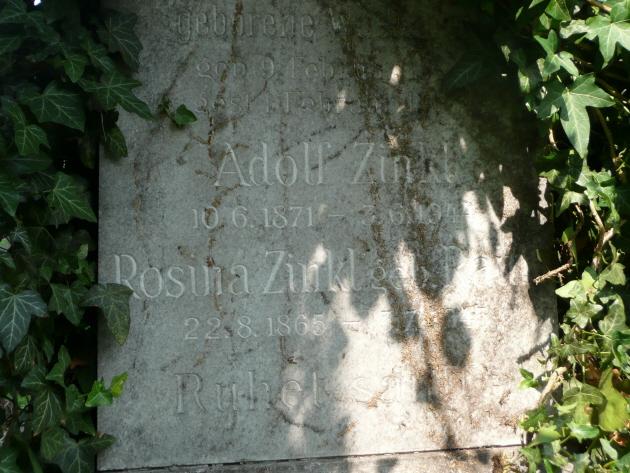

Michael Lorenz (Vienna) has discovered information about Adolf Zinkl’s death:

‘At the time of his death on 3 June 1944, at the age of almost 73, Adolf Zinkl was a retired employee of the postal service (Reichspost). His last address, as recorded on his Todfallsaufnahme, was Erdbergstraße 53/2 in Vienna’s third district. He was survived by his widow Rosina Zinkl née Raith (aged 79) and left no children or other relatives.

Zinkl was buried on 9 June 1944 in Vienna’s Zentralfriedhof (group 41/F, row 13, no. 15). The existence of his grave is guaranteed “auf Friedhofsdauer” (i.e. as long as the cemetery exists).’

(4839)

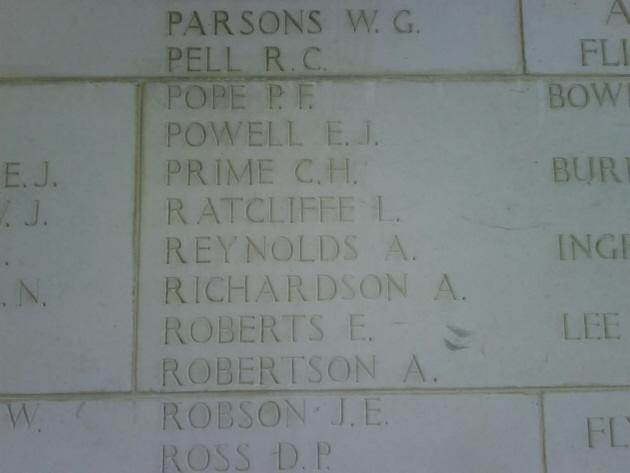

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘The War Graves Photographic Project gives details regarding Arthur Reynolds, who died on the Suez Maru, a Japanese cargo ship sunk on 29 November 1943. His name appears on a website providing an account of the event.

On 11 April 2009 I went to the Kranji War Cemetery, where the Singapore Memorial is located, and took a number of photographs, including the following:

(6075)

Olimpiu G. Urcan sends us, courtesy of Peter Michael Braunwarth (Vienna), photographs of Adolf Zinkl’s grave in the Zentralfriedhof Wien (door 2, group 41F, row 13, number 15):

(6685)

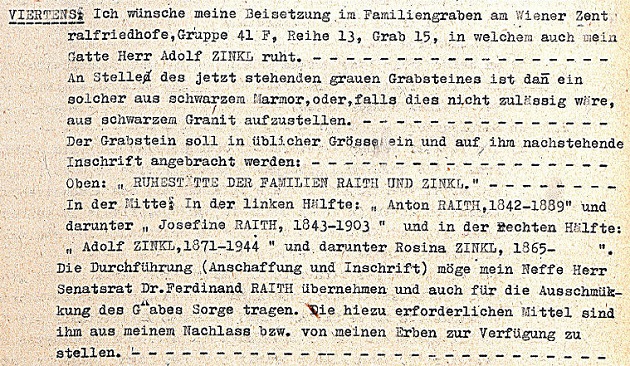

Michael Lorenz reports that in August 2019 he tidied the gravestone of Adolf Zinkl in the Zentralfriedhof Wien and took this photograph:

Our correspondent furthermore provides the fourth paragraph of the will of Zinkl’s widow, Rosina (1865-1945), written on 29 August 1944:

The request that the headstone be replaced with one made of black marble or black granite, to be bought by her nephew Senatsrat Dr Ferdinand Raith from his share of the inheritance, was not complied with, for unknown reasons.

(11483)

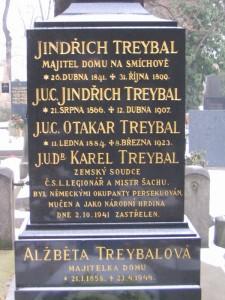

Jan Kalendovský submits a photograph of Karel Treybal’s gravestone in Prague:

The exact location is Prague 5 – U Smíchovského hřbitova 1, Malvazinky. For information about Treybal’s death (by execution on 2 October 1941) see C.N.s 3729 and 3733.

Karel Treybal

(5099)

Michael Lorenz has submitted a photograph which he took at Vienna’s Zentralfriedhof. Grünfeld was buried there on 9 April 1962.

(5733)

Our correspondent Michael Lorenz reports that, 11 years on, he has just revisited the grave, which is held privately (group 65, row 17, number 65):

We hope to be able to report soon that the authorities have carried out the necessary restoration and preservation work.

(11459)

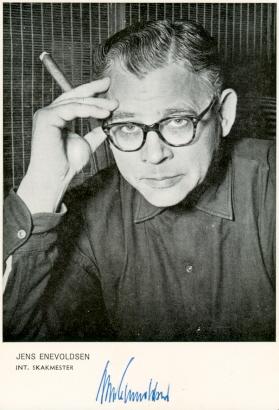

In C.N. 4307 (see above) Michael Negele presented a photograph taken by him of the Nimzowitsch-Enevoldsen ‘double grave’ in Copenhagen.

Phil Bourke (Blayney, NSW, Australia) asks why the two masters share the same resting place.

The matter was discussed on page 11 of Schaakgraven (the booklet mentioned in C.N. 4452 above). That publication relates that Nimzowitsch described Enevoldsen as ‘the hope of Danish chess’ after losing to him in the Copenhagen, 1933 tournament. Enevoldsen died in 1980, and in his will he expressed a wish to be buried alongside Nimzowitsch. The Danish Chess Union, the owner of the plot, acceded.

Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark) informs us:

‘Enevoldsen’s obituary by Poul Hage in Skakbladet, July 1980, pages 99-102 does not mention the matter, but I have checked the facts with Steen Juul Mortensen, who was the President of the Danish Chess Union in 1980. He confirms that Enevoldsen wanted to be buried alongside Nimzowitsch. His family made a contribution to the fund.

Nimzowitsch, for his part, had no family in Denmark when he died, in 1935. A number of chess friends created a fund to care for his grave, and the fund still exists today, administered by the Danish Chess Union.

As noted by Hage in the above-mentioned obituary in Skakbladet, Enevoldsen was a great admirer of Nimzowitsch, and they became friends in 1933. On page 150 of his autobiography 30 år ved skakbrættet (Copenhagen, 1952) Enevoldsen wrote about his victory over Nimzowitsch at Copenhagen, 1933 (my translation from the Danish):

“As you can imagine, the waves rose high when Nimzowitsch turned over his king. The master removed his glasses and wiped away the perspiration from his brow, stood up and disappeared. From all sides people shook hands with me and slapped me on the back. My elderly mother, who was a spectator that particular day, was as moved as when she became a grandmother ...

A few minutes later Nimzowitsch came back as calm and composed as would be expected. As a good sportsman he offered me his hand and thanked me for the game.

From that day on, he had tremendous respect for my play and never again regarded me with the usual lack of interest. In fact, we began to appreciate each other. Unfortunately, this lasted for only the two years that he had still to live. I am sure that he would have been happy to see the many games that I have played since then in his spirit and in accordance with his principles.”’

(5776)

The above photograph of Fernando Saavedra’s gravestone has been sent to us by Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands). It was among the papers of John Selman, whose son Frank gave it to our correspondent.

(5805)

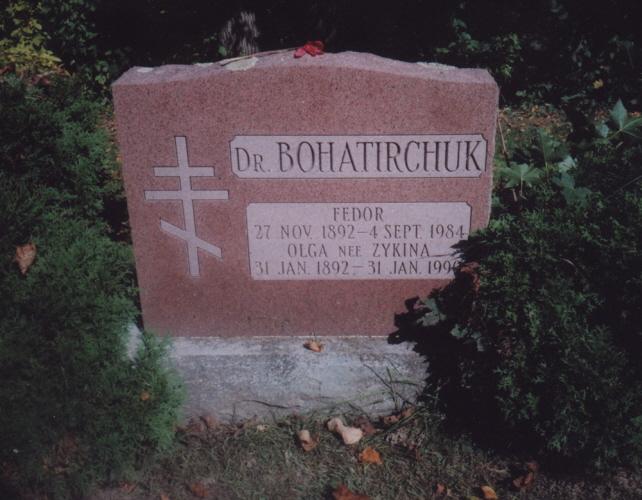

Yakov Zusmanovich (Pleasanton, CA, USA) sends this photograph, taken by Irene Ben-Tchavtchavadze, of the grave of Fedor Bohatirchuk:

(5816)

Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, Italy) informs us that on 2 November 2008 he took two photographs of the grave of Esteban Canal and his wife Anna Klupacs in Cocquio Trevisago, Italy:

Canal’s year of birth is given as 1893, whereas standard reference books (e.g. Chess Personalia and the Dizionario enciclopedico degli scacchi) state that he was born on 19 April 1896, in Chiclayo, Peru.

Our correspondent mentions that doubts as to the facts were expressed by Alvise Zichichi on page 2 of his book Esteban Canal (Brescia, 1991). According to Zichichi, Canal sometimes said in private that he was born before 1896 and in Spain, not Peru. The book also noted Giancarlo dal Verme’s statement in L’Italia Scacchistica, April 1981, pages 106-107, that Canal was born in Santander, Spain of a Spanish mother and a Peruvian father.

(5831)

Yakov Zusmanovich has sent us, courtesy of Sergei Voronkov, a photograph of David Bronstein’s grave, located in a cemetery (Чижовскоe) in Minsk, Belarus.

The photograph was taken by Bronstein’s widow, Tatiana Boleslavsky, who is the daughter of Isaac Boleslavsky.

(5859)

Marc Hébert (Charny, Canada) notes on page 192 of the 14/2007 Quarterly for Chess History a reference to ‘Aleksander (actually – Avrohom) Flamberg’ and asks for further information on the forename.

The writer of the article, Tomasz Lissowski, tells us:

‘Flamberg used the “modern” form of his forename, Aleksander, but the inscription on his grave at the Jewish Cemetery, Okopowa Str., Warsaw states that his first name was Avrohom.’

A photograph has been supplied by Mr Lissowski:

(5952)

From Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel):

‘Flamberg, like many European Jews, had two forenames – one “Jewish” (Avrohom) and one “Gentile” (Aleksander). The point of such double names (usually beginning with the same letter) was to make assimilation easier. One would use the Jewish name within the Jewish community, especially for religious purposes, and the Gentile one within the larger, Gentile world.

The Hebrew on the gravestone says:

“Here is buried

The bachelor Avrohom Alexander

Son of David Flamberg

Died on the tenth of the month of Shvat 5686

Aged 45 years

[mourned by] His parents and sisters.”Avrohom, Avraham, Abraham, etc. are all variant spellings (or pronunciations) of the same Hebrew name אברהם – i.e. the name of the biblical patriarch.’

(5963)

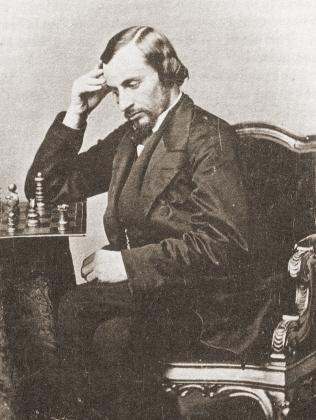

Daniel Harrwitz

From Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, Italy):

‘Standard reference works, such as Gaige’s Chess Personalia (page 163) and Chicco and Porreca’s Dizionario enciclopedico degli scacchi (page 266), give 9 January 1884 and Bolzano/Bozen as the date and place of Daniel Harrwitz’s death.

In July 2009 I checked the Totenbuch Number 12, 1884-1895 (Dompfarre M. Himmelfahrt, Bozen), page 1. It reported that Harrwitz died at 5 a.m. on 2 January 1884, at the age of 63, the cause of death being “lung paralysis” (“Lungenlähmung”). Under “Religion” it was stated “Israelit”, and his last address was “Zollstange 173” in Bolzano.

Following on from this information, I managed to find Harrwitz’s grave in the Jewish Cemetery in Bolzano. My photographs were taken on 17 July 2009, with the kind permission of the Jewish Community of Meran/Merano.

The gravestone has the following inscription:

“Hier ruhet

unser guter Bruder u. Onkel

Professor

D. Harrwitz

geb. in Breslau d. 22.2.1821

gest. in Bozen d. 2.1.1884.”

The death-date on the gravestone is the same as that given in the Totenbuch. Any remaining doubts about its correctness are removed by verification of what was published on page 4 of the Bozner Zeitung of 4 January 1884:

“Verstorbene im Bezirke Bozen.

(...)

2. Jänner. Dr. Harwitz [sic], led. Professor aus Breslau, 63 J. alt, an Lungenlähmung.”

It is therefore certain that his widely-reported date of death, 9 January 1884, is wrong.

Now I turn to his date of birth. The Totenbuch and the gravestone are significantly at variance with the information commonly given in such works as those by Gaige and Chicco/Porreca referred to above, i.e. 29 April 1823, in Breslau. The day, month and year are all different from what appears on the gravestone (22 February 1821). If the gravestone and the Totenbuch are correct, Harrwitz was born over two years earlier than was previously believed, and he died at the age of nearly 63.

The inscription on the gravestone indicates that Harrwitz was survived by relatives (“unser guter Bruder und Onkel”), which to me is a strong argument in favour of the correctness of the gravestone date.

It would be interesting to know whether any documentation in Breslau/Wrocław (Poland) confirms the birth-date on the gravestone.

For assistance with my research I should like to thank Pater Plazidus (Benediktinerkloster Muri-Gries, Bolzano/Bozen), Mrs Streiter (Dompfarre Maria Himmelfahrt, Bolzano/Bozen) and the Jewish Community of Merano/Meran.’

(6286)

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) informs us that Václav Kotěšovec has found and photographed the grave of Karel Opočenský in the Friedhof Vinohrady, Prague:

The photograph below is taken from Nad šachovnicemi celého světa by K. Opočenský and V. Houška (Prague, 1960):

Karel Opočenský

(6355)

Yakov Zusmanovich has forwarded a photograph, received from Sergei Voronkov, of the grave of Isaac Boleslavsky in a cemetery (Чижовское) in Minsk, Belarus.

The picture features Boleslavsky’s son, Stanislaw, and his daughter, Tatiana (David Bronstein’s widow). Our correspondent mentions that Boleslavsky’s grave is about ten paces away from that of Bronstein, his son-in-law (see C.N. 5859).

Isaac Boleslavsky (Source: Chess in Russia by P. Romanovsky (London, 1946), plate section)

(6389)

From Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

‘Some years ago I gave a lecture to the British Chess Problem Society about E.E. Westbury, an excellent composer whose work deserves to be better known. The text was reproduced in The Problemist and later added to the BCPS website. [Updated link.]

Recently I was contacted by the composer’s grandson, Ian Westbury, who found the website article while researching his family history. He sent me two photographs of his grandfather and two of his grave in Erdington, taken in 1939, the year he died. The grave is adorned with a marble board and pieces (the pieces have apparently disappeared over time) and has this inscription:

“Treasured memories of Eric Ernest Westbury, born June 11th 1881, died March 15th 1939 (International chess problemist and player). A tribute of affection from his beloved wife Kit and boys Kenneth and Roy. Oh true brave heart, God bless thee.”

It must be unusual for an epitaph to refer specifically to the deceased as a chess problemist, and I wonder whether there are any others. Eric Westbury certainly had international fame as a problemist, but I doubt that the “international” was intended to accompany “player”, although he played on top board for Worcestershire.’

Mr McDowell has also forwarded to us, courtesy of Ian Westbury, a photograph dated July 1924. Can any information be traced about the occasion (e.g. based on the trophy)?

Eric Ernest Westbury

(6457)

Piotr Hoffmann (Srem, Poland) requests information about Chigorin’s resting place.

(6753))

Some information about Chigorin’s grave is available in an article by his daughter which has recently come into circulation. Acknowledgement for this information: Wijnand Engelkes (Zeist, the Netherlands), Hassan Roger Sadeghi (Lausanne, Switzerland) and Stephen Wright (Vancouver, Canada).

(6758))

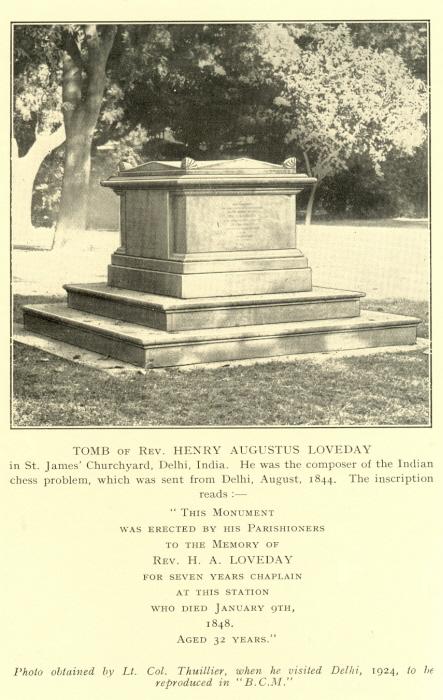

This illustration comes from opposite page 343 of the August 1925 BCM:

(6774)

Yakov Zusmanovich sends us, courtesy of Denis Shabalin and Sergei Voronkov, a photograph of Salo Flohr’s grave at the Vagankovo Cemetery in Moscow, shared with his second wife, Tatiana Flohr-Esenina:

(6794)

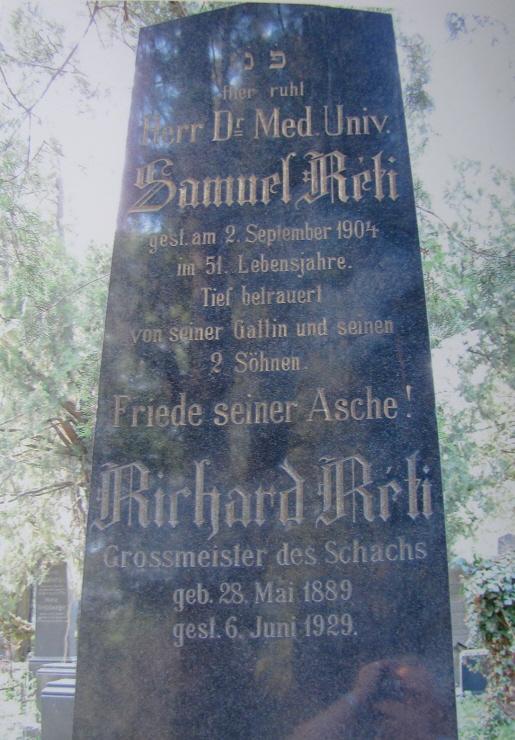

This photograph, taken by Miloslav Salomounek, has been sent to us by Jan Kalendovský:

We have also received a photograph from Stanislav Vlček (Bratislava, Slovakia):

The location is the Jewish part of the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna (Section T1, Group 51, Row 5, Grave 34), and Mr Kalendovský draws attention to an article about Réti’s grave.

(6821)

Concerning the grave of Richard Réti in the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna, we have received the following from Michael Lorenz (Vienna):

‘It is not Réti’s body that is buried there, but the urn containing his ashes. The urn was buried in Vienna on 30 June 1929. Owing to the cause of his death, Réti’s body had to be cremated in Prague.

The source for this information is the card catalogue of Jewish graves in the archive of the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde (IKG) in Vienna. The basic information (i.e. the location of the grave and the date of Réti’s burial) can also be accessed at the Abfrage Friedhofs-Datenbank webpage.’

(6854)

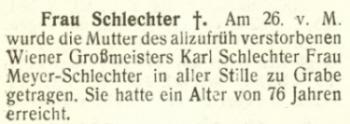

Maurice Carter (Fairborn, OH, USA) asks about the location of Carl Schlechter’s remains. His question arises from C.N. 1084, which is reproduced below:

Ludwig Steinkohl (Bad Aibling, Federal Republic of Germany) informs us of a letter he has received from Mr Egon Spitzenberger of Vienna, the Chairman of the Committee for Correspondence Chess of the Austrian Chess Federation, indicating that both Schlechter and his mother were buried in Catholic graveyards (the latter at Perchtoldsdorf, a suburb of Vienna, in the late 1930s).

The reference by Steinkohl to the late 1930s in connection with Schlechter’s mother was corrected in C.N. 1152 when Warren Goldman pointed out this report on page 76 of the March 1925 Wiener Schachzeitung:

Goldman added that the 1925 death-date was confirmed by church papers about the Schlechter family which were in his possession.

As Mr Carter remarks, the master’s death and burial were subsequently discussed on pages 45-47 of Carl Schlechter! Life and Times of the Austrian Chess Wizard by Warren Goldman (Yorklyn, 1994). It was noted, for instance, that writers such as Schonberg and Horowitz were ‘apparently blissfully unaware that Schlechter died in Budapest’ (as opposed to Vienna). In this connection, see the first item in Chess and Untimely Death Notices.

Schlechter was buried in Budapest, and a footnote on page 47 of Goldman’s book reads:

‘A last word concerning Schlechter’s final resting place: during a 1984 visit to Budapest, Herbert Huber of Vienna learned that the “honor grave” of 1918 no longer exists – the burial site in the Rakoskeressturer Cemetery having been closed by the Hungarian authorities some years ago. Whether Schlechter’s remains were moved to another location is unknown to the author.’

The discussion concerning Schlechter originated in C.N. 1055, where we noted the deletion of his name as a Jew in some versions of the anti-Semitic articles attributed to Alekhine. For further information on Schlechter’s religion (Catholicism), see Chess and Jews.

(6883)

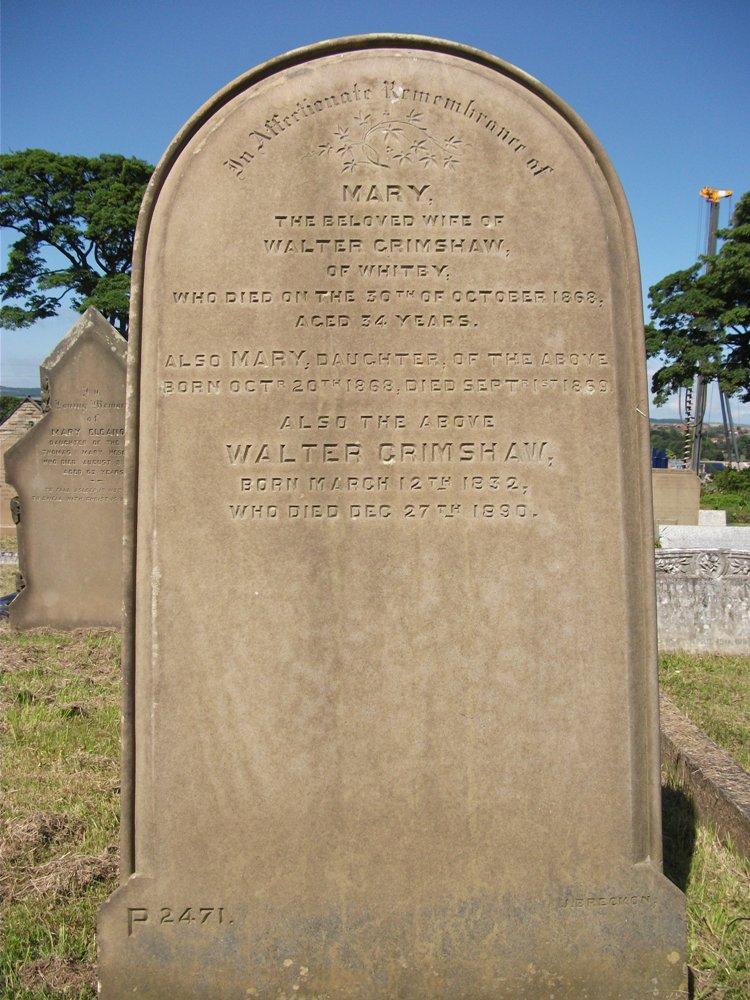

With regard to Walter Grimshaw, see C.N. 7271.

Alexander Rietema (Fort Lee, NJ, USA) has forwarded some photographs, which he took in late September/early October 2006, of the graves of Steinitz (Brooklyn, NY) and Lasker (Queens, NY):

It will be noted that the year of birth is incorrect.

(7794)

Tomasz Lissowski reports that Arthur Tartakower is buried in Kotowice Cemetery.

Source, found by Marek Lis (Opoczno, Poland): page 251 of Wielka Wojna na Jurze by P. and K. Orman (Cracow, 2008).

(8220)

For a note about Arthur Tartakower, the younger brother of Savielly, see C.N. 8198.

Photographs of the grave of Henry Michael Temple, the inventor of Kriegspiel, were shown in C.N. 9727. They include the following:

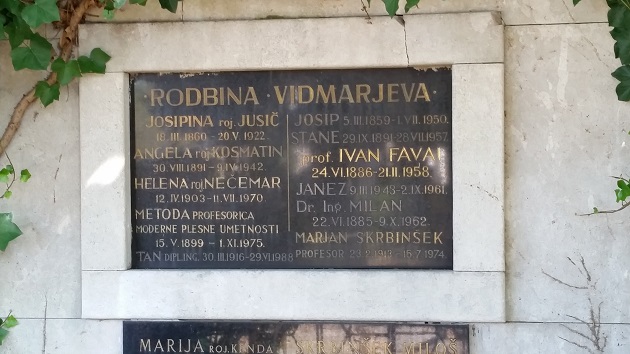

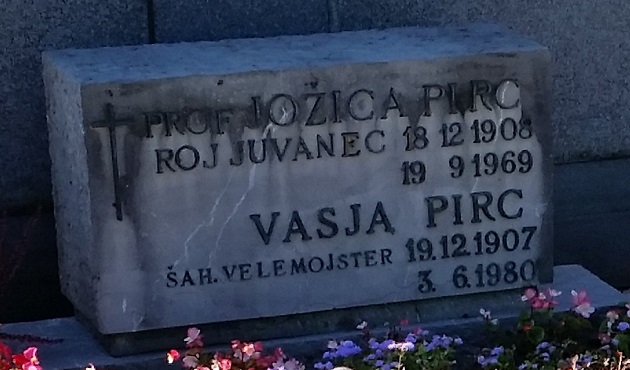

Jan Hessel (Rättvik, Sweden) reports that earlier this month he took these photographs in the Žale cemetery in Ljubljana:

(10627)

Cătălin Duminecioiu (Bucharest) reports that he has photographed the graves of Capablanca (November 2014) and Alekhine (summer 2016):

(11099)

Concerning the above photograph, see the contribution by Neil Hickman (Hardingham, England) in our feature article on G.H.D. Gossip.

From Michael Lorenz come two photographs which he took on 25 September 2019 in the Baumgarten cemetery in Vienna’s 14th district:

Our correspondent writes:

‘Hans Müller died on 28 February 1971 in the Sisters of Mercy Hospital, at Liniengasse 12, in Vienna’s Mariahilf district and was buried on 10 March 1971 in the grave number 2158 in group U in the Baumgarten cemetery. Müller had no children and was survived by two unmarried elder sisters, Hella and Maria Müller. On 18 January 1971, on his sick-bed, Müller had married his lifelong companion Friederike Madlmayr, whom he also appointed his universal heir. Friederike Madlmayr-Müller (as she signed her name) paid for the burial, a new headstone and – if the cemetery records are correct – also for the exhumation of Müller’s first wife Luise Müller (1896-1965), whose remains were transferred to Baumgarten from another cemetery. The fee for the grave was paid for a period of 30 years, and the right of use expired in March 2001. The headstone has gone.’

(11493)

Michael Lorenz sends two photographs of Alexander Halprin’s grave which he took on 24 May 2019:

Mr Lorenz writes:

‘As stated on pages 102-103 of the 5 March 1938 Wiener Schachzeitung, Alexander Halprin was buried at “Gruppe 10, Reihe 8, Grab 75” of the new Jewish cemetery at gate 4 of the Vienna Zentralfriedhof. His grave is the empty space to the left of the tree. The grave on the left (number 76 in row 8) is that of Sofie Morgenstern, who died on 20 May 1921 at the Rothschildspital in Währing.’

(11551)

Concerning this photograph, which he took at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow in February 2019, Douglas Griffin (Insch, Scotland) comments:

‘It shows the columbarium for Mikhail Botvinnik, his wife Gayane Davidovna and his mother Serafima Samoilovna.’

With regard to the cremation of Max Euwe, discussed in C.N. 4116 (see above), Mr Griffin notes that the Dutch National Archive site has four photographs.

(11569)

C.N. 11736 included the following pictures, courtesy of Cleveland Public Library Digital Gallery:

Michael Lorenz writes:

‘Adolf Albin is buried in Vienna’s Jewish cemetery at gate 4 of the Zentralfriedhof, group 6, row 13, number 45. The grave has no headstone but is between the two headstones in the foreground of this photograph, which I took on 24 May 2019:

The left-hand stone, number 46, is that of Chaim Ber Löwenheck, who died on 24 March 1920; the right-hand one, number 44, is that of Marie Aschenberger, who died on 26 March 1920. This was the burial area for, mainly, poorer members of Vienna’s Jewish population.

Albin’s wife is buried in another grave in the old Jewish cemetery, at gate 1 of the Vienna Zentralfriedhof, together with their daughter, Fanny, who committed suicide in 1896. It seems evident that Adolf Albin was due to be buried there too, but the existence of a family grave was not realized in 1920 because he left no will. His son, David Adolf, was born in Bucharest in 1874, and Fanny was born in 1877, also in Bucharest.’

In C.N. 11752 Michael Lorenz demonstrated that ‘Adolf Albin died on 22 March 1920 (and not 1 February 1920, as commonly stated)’.

Yuri Kireev (Moscow) has forwarded a photograph which he took in March 2019 of the memorial to Alexander Kotov at the Kuntsevsky Cemetery, Moscow:

(11762)

See too C.N. 3067 in Janowsky Jottings.

This photograph of Frank Skoff’s resting place is reproduced with authorization.

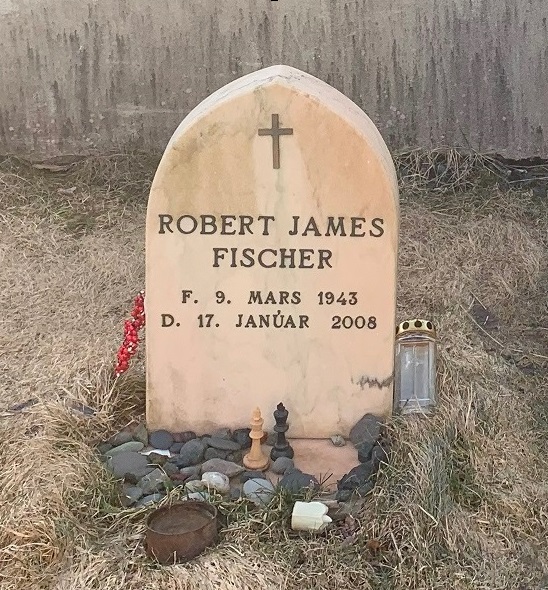

Bobby Fischer’s grave in Laugardælir, Iceland is shown in this photograph taken in March 2024:

Acknowledgement: Zachary Saine (Amsterdam).

See also Graves of well-known Chess Masters and Chess Personalities.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.