Edward Winter

Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart

From page 182 of Chess Review, August 1938:

‘“Unless Ray Milland is suppressed, he will have all Hollywood playing chess in another month or two.” (Jimmie Fidler in the New York Post).’

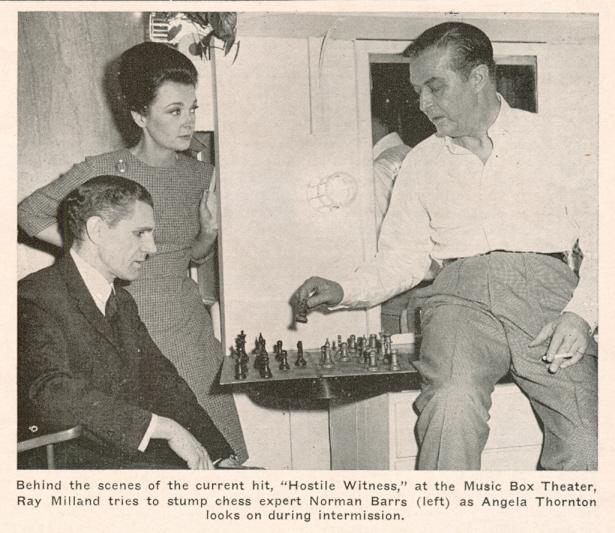

Chess Review, July 1966, page 195

(2567)

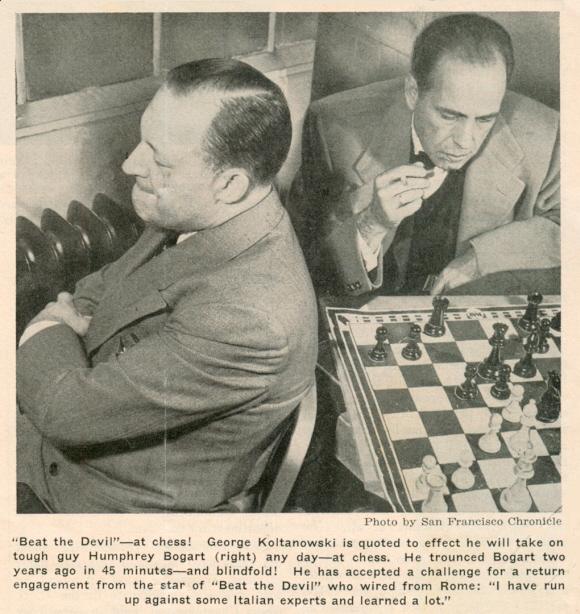

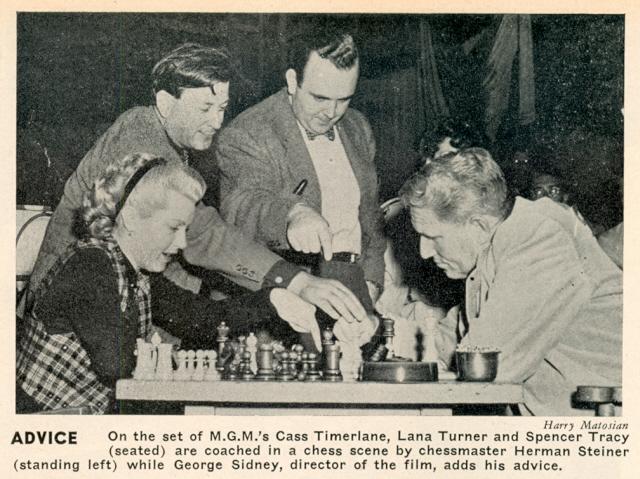

Chess Review, May 1954, page 131

Page 14 of the January-February 1943 American Chess Bulletin quoted the following from the New York Post:

‘Humphrey Bogart has started an idea that he hopes will be widely accepted. The Warner star is playing long distance chess games by mail with boys in the service.

It all started when a private, then stationed in this country, visited the set of Casablanca, still at the Hollywood Theatre where Bogart was playing chess with Sydney Greenstreet between scenes. The private offered to take on Bogart and a keen rivalry developed.

When the solider was transferred to the South Pacific, he kept up the game by mail. Since starting the game with the solider, Bogart has taken on several of his buddies by mail, playing simultaneously.’

(2610)

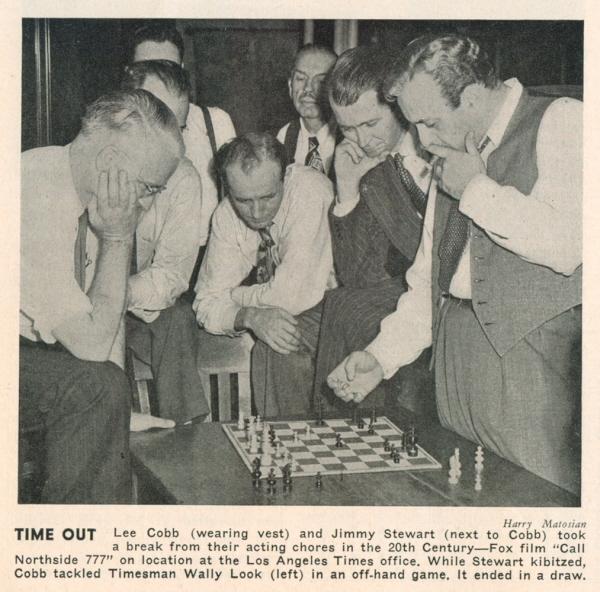

Chess Review, February 1949, page 4

(2641)

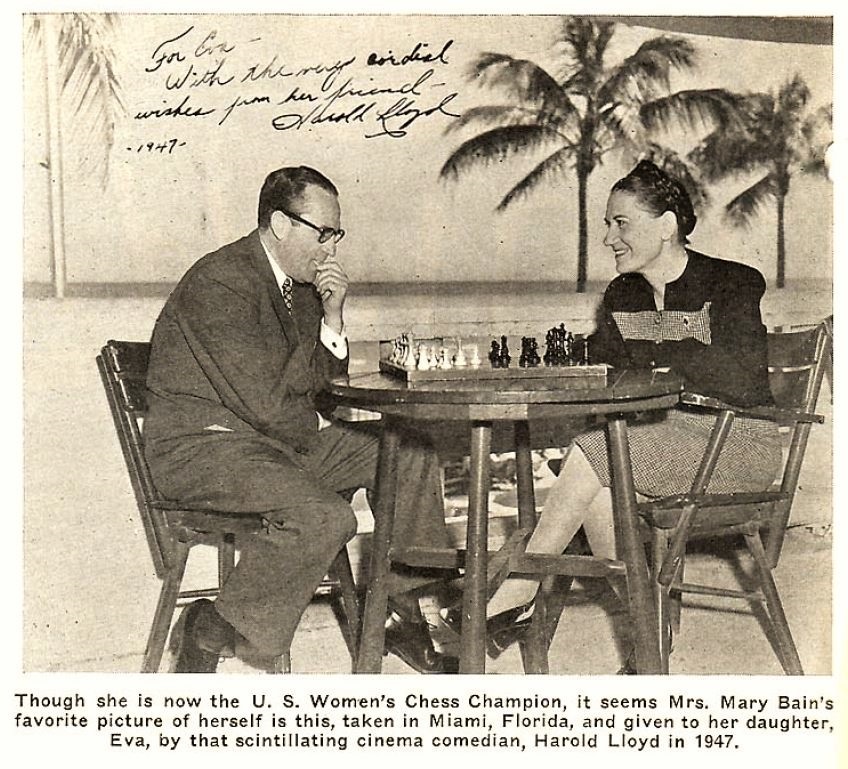

A photograph of Harold Lloyd with Mary Bain on page 356 of the December 1951 Chess Review:

(2678)

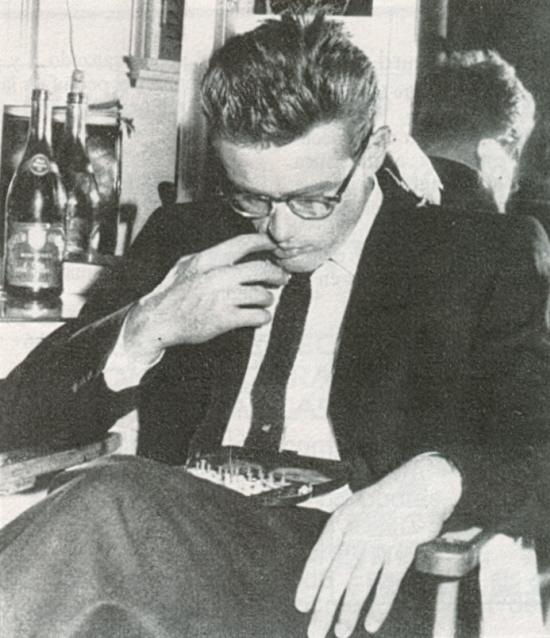

James Dean (Revista Internacional de Ajedrez, January 1992, page 53)

The Gambit, July 1930 (pages 189-190) contained an item dated 19 June which began as follows:

‘Lively interest of the picture world in the newly organized Beverly Hills Chess Club was emphasized last Thursday evening when Cecil B. deMille, the famous producer, sent in his membership and was elected to the board of directors.’

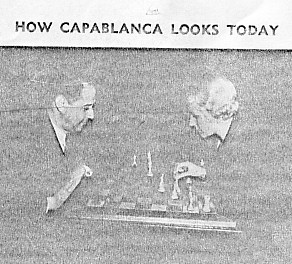

It may be recalled that he refereed Capablanca’s game of living chess (Los Angeles, 1933) against Herman Steiner (see page 115 of The Unknown Capablanca by D. Hooper and D. Brandreth).

(2848)

See also our feature article Capablanca v Steiner (Living Chess).

From John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA):

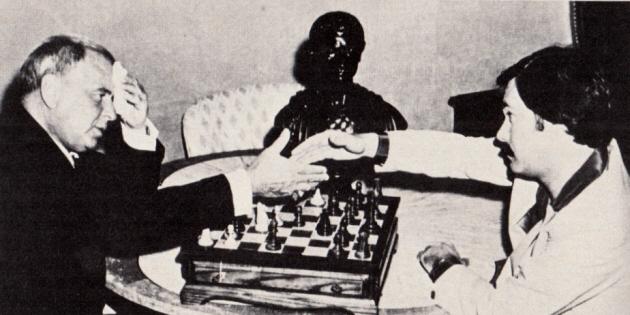

‘I have seen pictures of Capablanca and Steiner from Los Angeles 1933, but, until now, not this one with Cecil B. deMille:

It comes from the archives of Jacqueline Piatigorsky, whose chess mentor was Herman Steiner, and has been made available thanks to her family.’

It will be noted that Steiner has the white pieces. A detail of the position is provided.

(8030)

We see no reference to chess in The Autobiography of Cecil B. deMille edited by Donald Hayne (London, 1960).

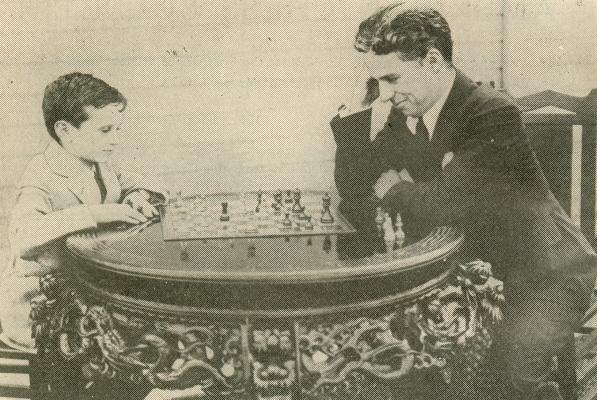

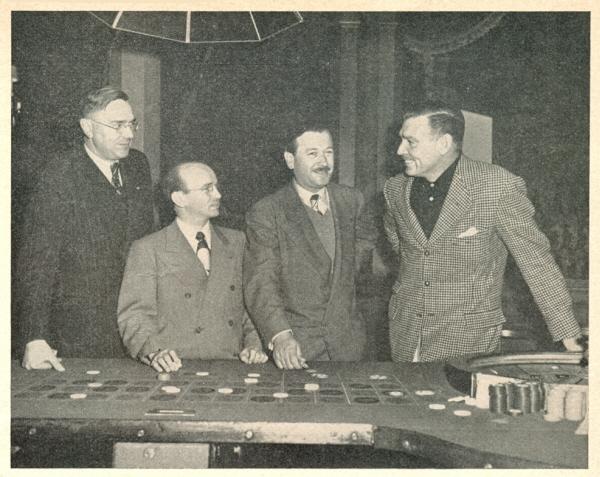

C.N. 198 briefly discussed the meeting in the early 1920s between Reshevsky and Charlie Chaplin. There are two well-known photographs of the celebrities in play against each other; in addition, page 191 of Chess Life & Review, April 1979 reproduced a shot of the prodigy watching a game between Douglas Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin.

A decade or so ago we noted that the following alleged game between Chaplin and Reshevsky had been published on page 414 of Şah Cartea de Aur by Constantin Ştefaniu (Bucharest, 1982), with a claim (devoid of any source) that it had been won by Reshevsky in New York in 1923:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 d4 exd4 4 e5 Ne4 5 Qe2 Nc5 6 Nxd4 Nc6 7 Be3 Nxd4 8 Bxd4 Ne6 9 Bc3 Be7 10 Nd2 O-O 11 Ne4 d5 12 O-O-O Bd7 13 Ng3 c5 14 Bd2 b5 15 Nf5 d4 16 h4 Nc7 17 Nxe7+ Qxe7 18 Bg5 Qe6 19 Kb1 Nd5 20 g3 Nb4 21 b3 Qa6 22 a4 Qa5 23 Kb2 bxa4 24 Ra1 Rab8 25 Kc1 a3 26 Bd2 Be6 27 Bxb4 cxb4 28 Qa6 Qc5 29 Bc4 Rbc8 30 White resigns.

We submitted the game-score to Frank Skoff, who scrutinized the matter in considerable detail in Chess Life, December 1992 (page 37) and June 1994 (page 10), reaching the following conclusion:

‘The game is a myth, to phrase it delicately, though some would bluntly call it a hoax. All that is left is the score, the origin of which is practically impossible to track down since it would have been copied from any game anywhere, or perhaps even composed by the perpetrator, man the myth-making animal in either case.’

Samuel Reshevsky and Charlie Chaplin (American Chess Bulletin, January 1922, page 2)

(2875)

Further to our material on page 258 of Chess Facts and Fables and in C.N. 7236, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found this report on page 18 of the New York Evening Telegram, 28 December 1921:

(7531)

Olimpiu G. Urcan also points out the Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo website. A search for ‘Schach’ yields many photographs of chess masters past and present. We note, for instance, a 1921 shot of Samuel Reshevsky boxing against the Hollywood prodigy Jackie Coogan.

(7784)

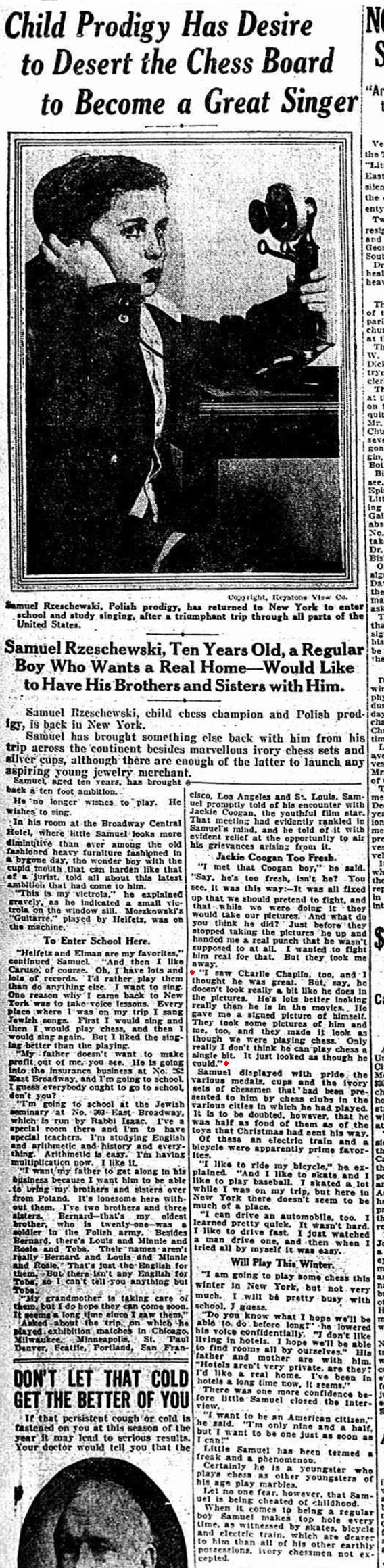

Max Euwe, Samuel Reshevsky, Herman Steiner and Clark Gable (Chess Review, March 1949, page 69)

(2931)

Chess Review, July 1947, page 5

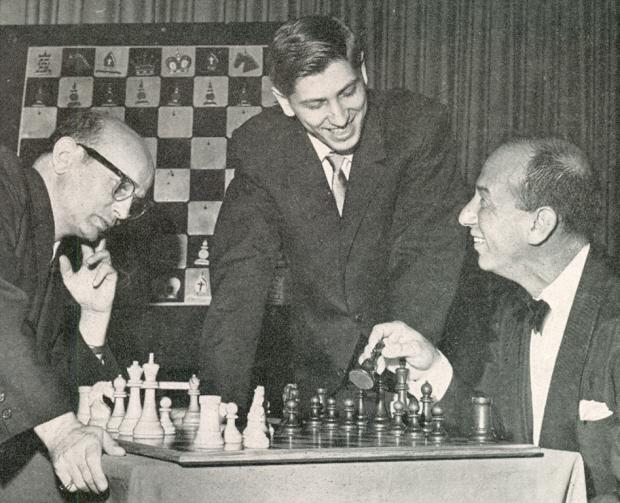

Samuel Reshevsky, Bobby Fischer and José Ferrer (Chess Review, September 1961, page 267)

Which musical composer wrote, in consecutive years, two entirely different pieces which were both entitled The Chess Game?

(2978)

The composer was Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957). They were featured in the Errol Flynn films The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939) and The Sea Hawk (1940). Numerous recordings of the scores are available, the most complete ones apparently being from Varese Sarabande (VSD-5696 and VSD-47304 respectively).

(2986)

From Chess Life, 20 April 1961, page 117:

‘Frances Parkinson Keyes’ novel The Chess Players is under negotiation as a possible motion picture. Dealing with the life and love of Paul Morphy, there is speculation that Bobby Fischer may play the role of Morphy in the movie.’

(2982)

The tale that Capablanca ‘once’ refused to be photographed with an actress (‘Why should I give her publicity?’) is well known, but what are its origins?

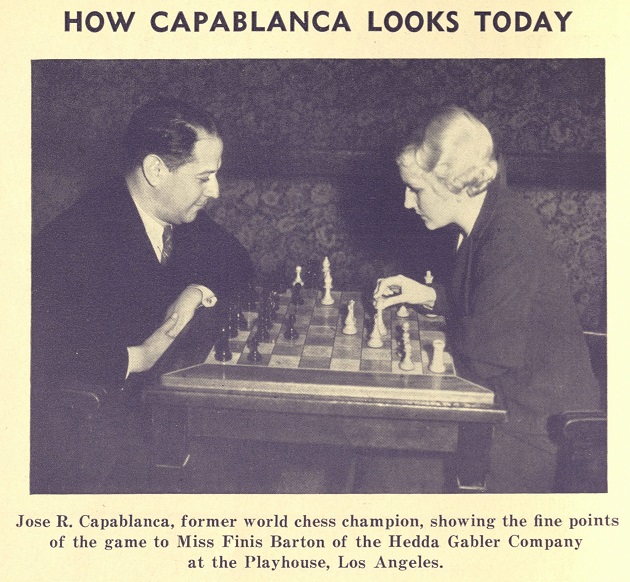

Two shots of him with Hollywood actresses come to mind. The first we have available only in poor photocopy form, from an unidentified source which has this caption beneath: ‘José R. Capablanca, former world chess champion, showing the fine points of the game to Miss Finis Barton of the Hedda Gabler Company at the Playhouse, Los Angeles.’

The other item on that page is a crosstable of the ‘Southern California Major League Race’, a chess event won by Beverly Hills with six points out of seven, and we hope that this clue will permit a reader to trace the source and send us a better copy of the above picture.

The second shot comes from the end section of volume one of Capablanca Leyenda y Realidad by Miguel A. Sánchez (Havana, 1978). It is identified as ‘Con Kay Frauce en Hollywood, 1933’, but Kay Francis was meant. [See, however, C.N. 5996 below.]

(3454)

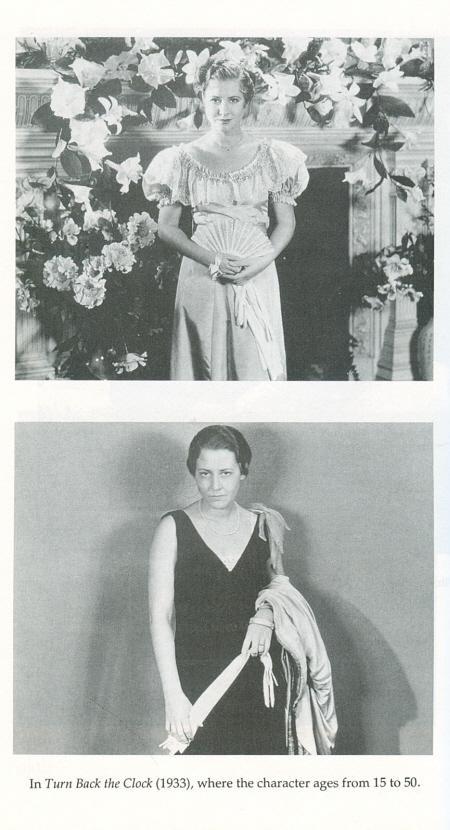

Lawrence Totaro (Las Vegas, NV, USA) sends this photograph of Mae Clarke (1910-92) with Capablanca in 1933:

A typewritten paragraph on the reverse side states that Capablanca ‘was the guest recently of Mae Clarke, actress, on the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer set making Turn Back the Clock’.

Capablanca was in Los Angeles in April 1933 (C.N. 4151). We see no mention of him in Featured Player An Oral Autobiography of Mae Clarke edited by James Curtis (Santa Barbara and London, 1996). The two photographs below come from that book:

(5996)

Further to C.N. 3454 above, which gave a small, poor-quality photograph of Capablanca at the chessboard with Finis Barton (1911-78), Olimpiu G. Urcan has found another shot, on page 10 of Part II of the Los Angeles Times, 11 April 1933:

Can a high-quality copy of the photograph be found?

Regarding the game referred to, see Capablanca v Steiner (Living Chess).

(11598)

The photograph shown in C.N. 3454 has been traced to page 2 of the North American Chess Reporter, April-May 1933. Below, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, is a fine copy:

(11606)

From Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) comes a photograph (source unknown) of Alekhine at the studios of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer with Renée Adorée (1898-1933) and Fred Niblo (1874-1948):

Can it be confirmed that the photograph was taken during Alekhine’s visit to Los Angeles in May 1929?

(5915)

In C.N. 5915 we tentatively suggested that a photograph of Alekhine at MGM was taken during his visit to Los Angeles in May 1929.

David Picken (Greasby, England) and Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) note that Renée Adorée played the role of a gypsy in an MGM film directed by Fred Niblo, Redemption. Shot in 1929 and starring John Gilbert, it was not released until 1930. Without the production delays it would have been his first talking picture.

We add that Redemption was unsuccessful, as noted, for instance, on page 66 of La fabuleuse histoire de la Metro Goldwyn Mayer en 1714 films (Paris, 1977). See also pages 261-262 of volume one of The Great Movie Stars by D. Shipman (London, 1989). According to page 544 of Close-Ups From the Golden Age of the Silent Cinema by J.R. Finch and P.A. Elby (New York and London, 1978) Gilbert’s ‘greatest film was The Big Parade with Renée Adorée’.

(5922)

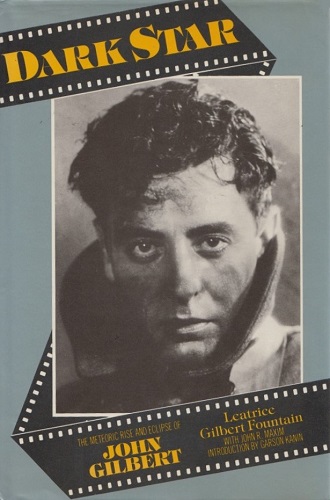

In connection with a photograph of Alekhine in Hollywood, C.N. 5922 referred to the actor John Gilbert (1899-1936). Information about his possible interest in chess is sought.

His daughter Leatrice Gilbert Fountain wrote a biography of him, Dark Star (London, 1985), and on page 253 she recalled that on Christmas Eve 1935, when she was 11, the many gifts (‘wonderful impractical things’) which John Gilbert gave her included an ivory chess set.

(10542)

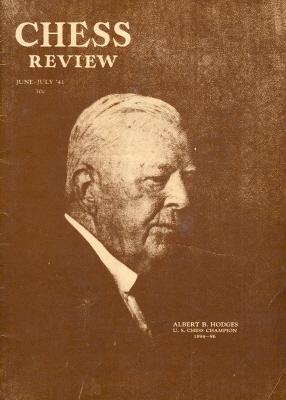

C.N. 2221 raised the subject of the first chess master to act in a film. We suggested A.B. Hodges (1861-1944), on the basis of the following ‘Hodges in the Movies’ item on page 47 of the February 1918 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Albert B. Hodges, ex-United States chess champion, has made a number of appearances on the screen, notably as a member of the Russian Duma in War Brides, the Police Inspector in The Auction Block, the Coroner in Empty Pockets and the Butler in the new Brenon picture False Faces.’

Can any reader discover information about Hodges’ acting career?

Albert Beauregard Hodges

(3806)

As regards Albert B. Hodges’ alleged involvement in films in the second decade of the twentieth century, David Picken (Greasby, England) writes:

‘I have searched in the Internet Movie Database and the All Movie Guide database but have found nothing on Hodges, although the four films you mentioned are covered and cast-lists are given. It may be that Hodges was an “extra” or a very small bit part player who would not normally be credited. The films are:

War Brides. Released in 1916 as a short (eight minutes) by Selznick Pictures Corporation and directed by Herbert Brenon. The cast included Alla Nazimova and Richard Barthelmess.

The Auction Block. Released in 1917 and directed by Laurence Trimble.

Empty Pockets. Released in 1918 and directed by Herbert Brenon.

The False Faces. Released in 1919 and directed by Irvin Willat. Brenon appears not to have had a connection with this film.’

(3813)

Although many of the key details remain elusive, all available information on this aspect of the master’s life is presented on pages 314-315 of an admirable new book, Albert Beauregard Hodges (subtitle: The Man Chess Made) by John S. Hilbert and Peter P. Lahde (Jefferson, 2008).

A.B. Hodges, front cover of the Chess Review, June-July 1941

(5737)

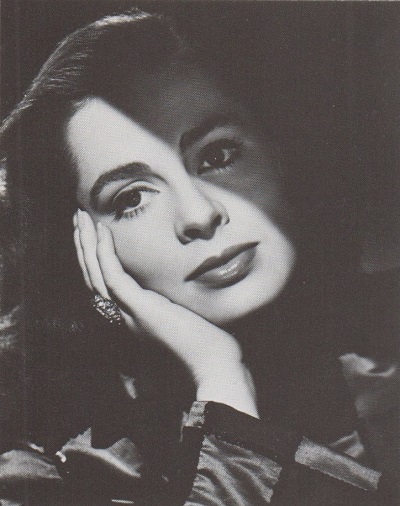

Some years ago (see pages 230-232 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) we discussed chess connections involving Viveca Lindfors and Errol Flynn, who co-starred in the 1948 film Adventures of Don Juan. In passing we described Viveca Lindfors as ‘the only screen goddess lucky enough to marry a FIDE President’ (i.e. Folke Rogard). This 1946 photograph of the couple appeared in her autobiography Viveka ... Viveca (New York, 1981):

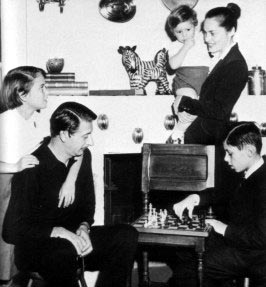

She was later married to the actor and writer George Tabori, and her book also has the following shot, ‘the first picture of the Tabori-Lindfors family in the house on 95th Street’:

A photograph of Viveca Lindfors from opposite page 63 of Viveka ... Viveca:

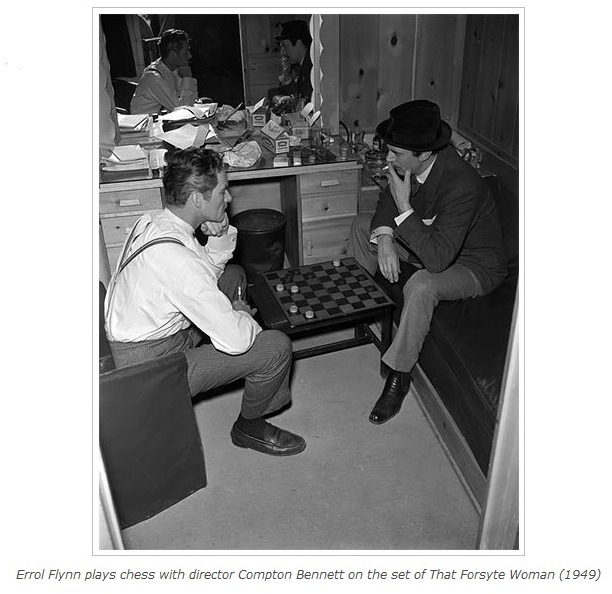

Errol Flynn (1909-59) is chiefly remembered for his swashbuckling films and off-screen embroilments, but he was also a vividly eloquent novelist and journalist.

He received a brief mention on page 79 of the 14 November 1937 issue of CHESS:

‘Errol Flynn is another film-star chess-ite.’

Page 61 of Errol Flynn in Northampton by Gerry Connelly (Corby, 1995) reported:

‘Flynn might not have been an Einstein or a Socrates, but he always took intelligent approaches to his film rôles, played chess well, could converse in a number of exotic languages, and worked productively as a writer.’

Flynn himself took lightly the claims made on his behalf. In an article entitled ‘My Plea for Privacy’ published in Screen Guide in 1937 he wrote:

‘As to my private life – well, there’s precious little of it left – but according to what I read in the newspapers, I am a master of such minor arts as boxing, fencing, wrestling, jiu-jitsu, horsemanship, hunting, fishing, sailing, swimming, golf, tennis, chess, trap-shooting and jacks. I get up early in the morning and after dashing through Beethoven’s Etude in B Minor I casually practise each and every one of the above sports, sometimes doing a little Indian club work with my disengaged hand.’

A photograph of Errol Flynn playing chess appeared in the book From a Life of Adventure: The Writings of Errol Flynn edited by Tony Thomas (Secaucus, 1980). Taken during the shooting of his 1942 film They Died with Their Boots On, it showed him locked in combat with Olivia de Havilland.

From our collection comes this photograph of Errol Flynn, inscribed by him in 1940:

And, as a tailpiece, an extract from page 8 of the new Gambit Publications book Secrets of Attacking Chess by Mihail Marin (London, 2005):

‘I am sure most of us have been captivated by the cape and sword movies of the 1960s, featuring such fine actors as Errol Flynn.’

Not exactly. Flynn died in 1959.

(3868)

What on earth has happened to the standards of accuracy and integrity usually applied by ChessBase.com in the past?

There is, for instance, an individual named Albert Silver who cobbles together articles by indiscriminately hoovering up images instantly available via an Internet search.

As regards the indiscriminate nature of his ‘work’, below is what appeared in (but has since been removed from) an article of his about chess and film stars which ChessBase.com posted on 23 February 2015:

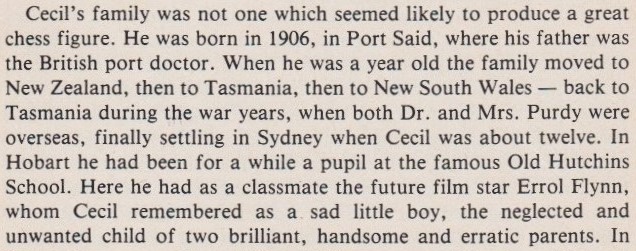

From page 14 of C.J.S. Purdy, His Life, His Games and His Writings by J. Hammond and R. Jamieson (Melbourne, 1982), in the chapter ‘C.J.S. Purdy – His Life’ by Anne Purdy, his widow:

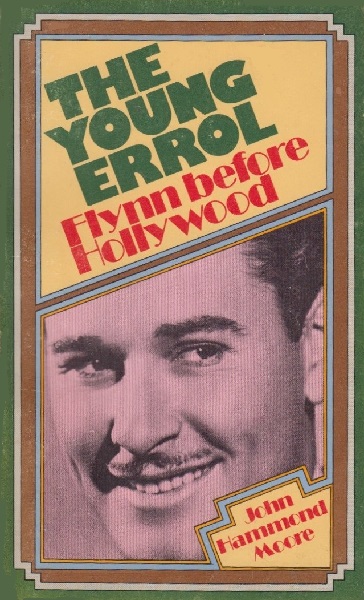

The Hutchins School was mentioned on pages 13-15 of The Young Errol by John Hammond Moore (Sydney, 1975), which asserted that Errol Flynn (born on 20 June 1909) was a pupil there:

‘Errol began his formal education at the Franklin House School on Davey Street, but by 1918 was enrolled in the junior division of the Hutchins School, Hobart’s most prestigious private, old-tie institution for miniature bluebloods.

... Errol lasted only one more term at Hutchins. (Australian schools traditionally operate on three terms of several months each from February to December.) In April of 1920 he entered Friends’ School ...’

Different information is on pages 7 and 9 of Errol Flynn The Tasmanian Story by Don Norman (Hobart, 1981):

‘Errol first attended Franklin House School in July 1916, which was later incorporated in Hutchins Junior School in June 1917 ... Hutchins School is a prestigious establishment for boys begun in 1846 and modelled on the lines of the upper class English schools.

Errol went with the boys of Franklin House School to Hutchins Junior in June 1917, but remained there for only a short time before attending Albuera Street Model School ...

There is no explanation as to why Errol was taken away from Albuera Street School when he was ten years and ten months old and placed as a boarder at Friends School, a long established academy for girls and boys. He was nine months at Friends leaving on 20 December 1920.’

(11706)

See too C.J.S. Purdy.

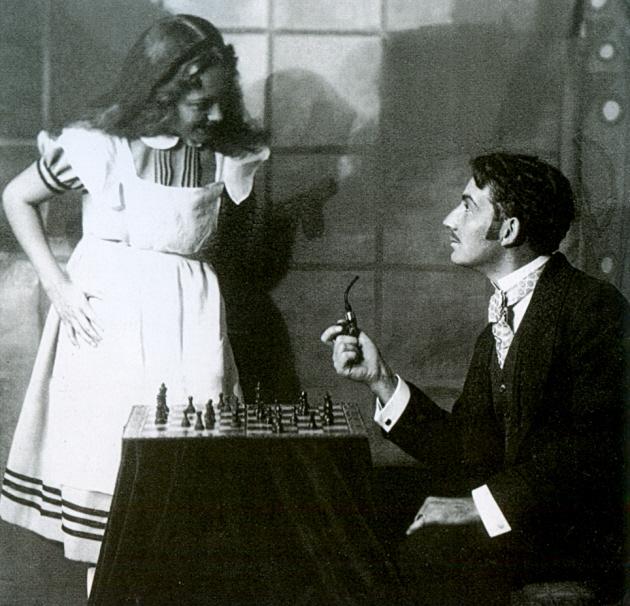

Here is another photograph of Olivia de Havilland, from page 4 of Errol & Olivia by Robert Matzen (Pittsburgh, 2010):

The caption reads: ‘To escape an unhappy home life, Olivia de Havilland finds a creative outlet with the Saratoga Community Theatre. Here, at age 16, she plays Alice in Alice in Wonderland, her first acting role.’

(7095)

From Stephen Wright (Vancouver, Canada):

‘Your feature article on Alekhine v Kimura mentions the English player Mr Havilland. I do not think that it has been widely realized that this was Walter de Havilland, the father of the film stars Olivia de Havilland and Joan Fontaine. In later life his home was in British Columbia.’

On his British Columbia Chess History website our correspondent has written an article about Walter Augustus de Havilland (1872-1968).

(12147)

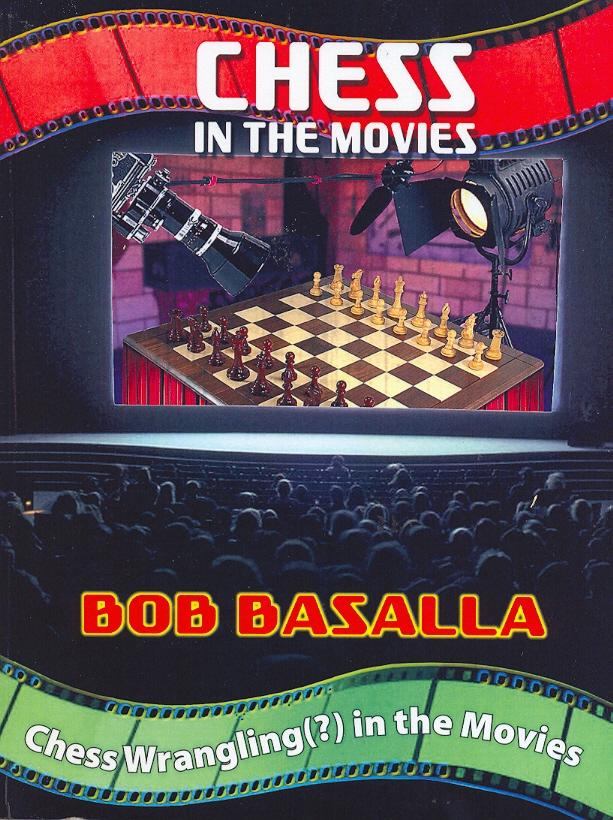

From the outset (i.e. even before the book arrived) we had rather low hopes of liking Chess in the Movies by Bob Basalla (Davenport, 2005), largely because of the dreaded words ‘vanity press’. When, however, the volume turned up, it immediately created a favourable impression as a well-produced 422-page paperback (large-size, in A to Z encyclopaedia format) containing a remarkable amount of fresh information.

Yet as we began to browse, focusing on productions about which we have written, disappointment took the upper hand. C.N. 3858 quoted P.H. Williams (in 1919) on the chess-related poster for The Summer Girls, but the book had no entry for it and there was no way of knowing whether this was an oversight or whether it was only the poster, and not the film itself, which had chess content. Then we looked at the brief entry for the 1987 Cuban/Soviet production Capablanca (pages 61-62). ‘The details I have gathered are sketchy’, writes Basalla, yet the film is readily available in video-cassette format. Nor was it encouraging to read on pages 393-394 that the 1925 Soviet film Chess Fever included documentary footage of Gideon Ståhlberg, who belonged to a later period or, on page 73, concerning the same film, that F.D. Yates was Canadian. Next, we consulted the entry (pages 94-95) for the 1984 Swiss film Dangerous Moves, where Basalla observes that the chess games were ‘created, the credits tell us, by someone named Nicolas Giffard’; whatever may be thought of Giffard’s chess writings, that seems an unattractively disparaging reference to an international master. We turned to the entry (pages 236-238) on The Most Dangerous Match, the chess-related episode of the television series Columbo. In the first paragraph the actor who played the murder victim is misidentified (it was Jack Kruschen, not Lloyd Bochner). Moreover, Basalla appears unaware of the circumstances of the position presented on page 237 (see Chess and Television).

All this was a poor start for Chess in the Movies, and it was a relief to find on pages 152-153 a good account of the Canadian production The Great Chess Movie (although Basalla really might have been expected to know that the problem attributed to Pope John Paul II is a hoax) and to see the author demonstrating fine critical faculties on pages 293-296 in his detailed discussion of Searching for Bobby Fischer. As we continued, examining other entries for films with which we could claim familiarity, a strange thing happened: the série noire had ended, and Chess in the Movies was growing on us. Basalla’s love of both chess and the cinema is evident, and he has put an extraordinary amount of research into what is, after all, a brave venture, given that no remotely comparable book exists. He states on page 12 that errors are likely in such a large work, and of course they are inevitable in any book of substance. Chess in the Movies, which is available from Amazon, will certainly be scrutinized avidly by readers around the world, and the author invites corrections. We look forward to the prospect of a superb second edition.(3986)

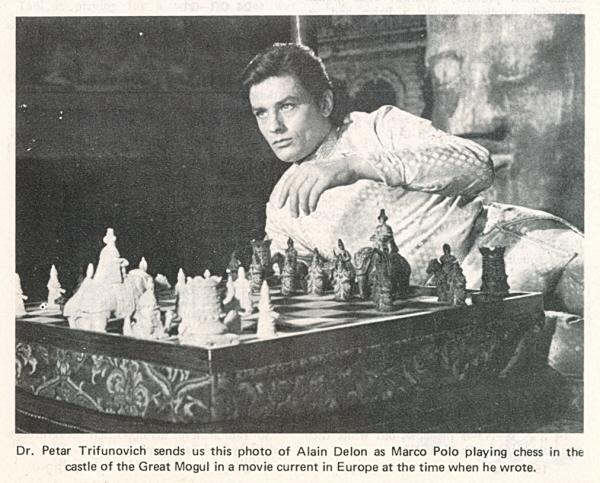

Alain Delon (Chess Review, September 1968, page 265)

C.N. 2865 (see page 75 of Chess Facts and Fables) asked for relevant information about the actress Marie Dressler (1869-1934), given that page 218 of Chess: Man vs Machine by Bradley Ewart (London, 1980) mentioned her ‘among the notables who were said to have played Ajeeb at the Eden Musée and were invariably defeated at chess or checkers’. Corroboration is still being sought, no progress having been made so far.

Front cover of a supplement to The Picturegoer, 1933

(4568)

C.N. 4229 referred to an Austrian webpage with a collection of chess postcards. Page two of the ‘Herren’ section features the photograph of Rudolph Valentino mentioned in C.N. 3097 (see page 108 of Chess Facts and Fables). Further details are sought, and particularly since in the biographies of the silent film star (1895-1926) we recall no mention of chess.

(4758)

Luc Winants has forwarded to us the photograph of Rudolph Valentino (1895-1926) referred to in C.N. 4758. It comes from the collection of Daniël De Mol, to whom we are also grateful.

(4788)

See too Chess Jottings.

From pages 319-320 of Harpo Speaks! (New York, 1961), the autobiography of Harpo Marx:

‘One day [in Moscow, autumn 1933]when there was no matinee I ducked out and went looking for some kind of action. In front of a good-sized theatre, one I hadn’t been in yet, there was an unusually long line of people. The line wasn’t moving. No tickets were being sold. It had to be something sensational with this many people waiting for a chance to get in.

Since the day I bought my outfit at the government store I had become used to the idea that foreigners didn’t stand in line. I went up to the box office and waved a dollar bill in the window. The cashier grabbed the buck and gave me a ticket. Valootye – foreign currency – worked like magic in Moscow.

The house was packed, and noisy. Most of the audience were standing or walking around, chatting, drinking and eating. Others were sleeping or reading. I had apparently come in during the intermission. Yet the curtain was raised and the stage was lit. Oddest of all was the setting on the stage. There was a small table and a chair. On the table were two telephones, and a bunch of knickknacks. Behind the table was a large, tilted mirror.

It was the longest intermission I ever sat through. Fifteen minutes passed. Twenty minutes. Twenty-five. Nobody seemed to mind waiting that long for the next act.

Then a buzzer sounded. People damn near trampled each other to get back to their seats. In 30 seconds the theatre was silent as a tomb. Everybody was watching the empty stage.

A boy, maybe ten or eleven years old, walks out from the wings. He sits at the table. He picks up the receiver of one of the telephones. He listens for a while, then hangs up without saying anything. He moves one of the little props on the table. The joint is so quiet I can hear my wrist watch ticking. The boy moves another knickknack. A guy comes out, walks to the footlights, announces something to the audience, and the joint goes wild.

People jump to their feet. They yell and throw their hats in the air and embrace each other. The guy who made the announcement shakes hands with the boy and the cheers are deafening. This is absolutely the craziest show I ever saw.

Finally it dawned on me what I had been watching. A chess match.

The kid on the stage, I found out, had been playing the Polish chess champion and the Ukrainian champion, by long-distance telephone. It was nice to know the home team won, but it would have been nicer if I could have gotten my dollar back.’

A slightly abridged version of this text appeared on pages 206-207 of King, Queen and Knight by Norman Knight and Will Guy (London, 1975), where Harpo Marx’s dates were given as ‘1893-1965’ instead of 1888-1964. Knight and Guy added:

‘There seems to be some mystery about the identity of this Soviet boy prodigy.’

Can readers provide any information?

(5483)

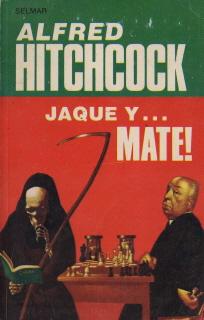

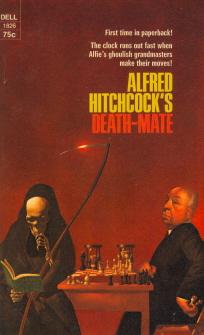

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) draws attention to the front cover of Jaque y ... mate! (Montevideo, 1976), a collection of mystery stories selected by Alfred Hitchcock:

The English edition was entitled Death-Mate (New York, 1973):

(5530)

Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, Italy) informs us of a new novel about Capablanca, by Fabio Stassi: La rivincita di Capablanca (Rome, 2008):

(5758)

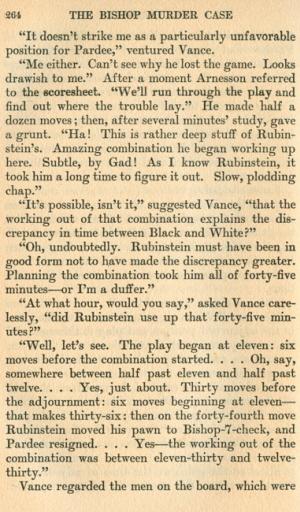

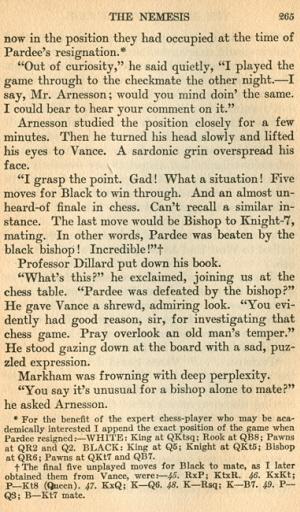

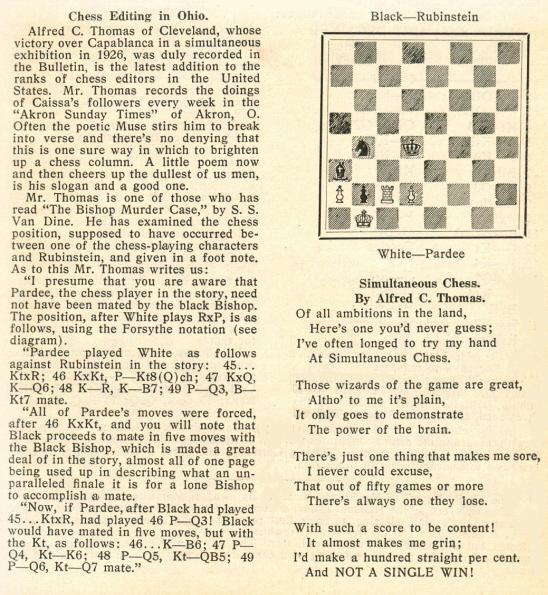

Albert Frank (Brussels) asks which crime novel featured A. Troitzky’s famous study (Novoye Vremya, 1895) with mate administered by a single bishop.

It was The Bishop Murder Case by S.S. van Dine (New York and London, 1929). We reproduce pages 264-265 of the edition published by Grosset & Dunlap, New York:

Below is an item from page 55 of the March 1929 American Chess Bulletin:

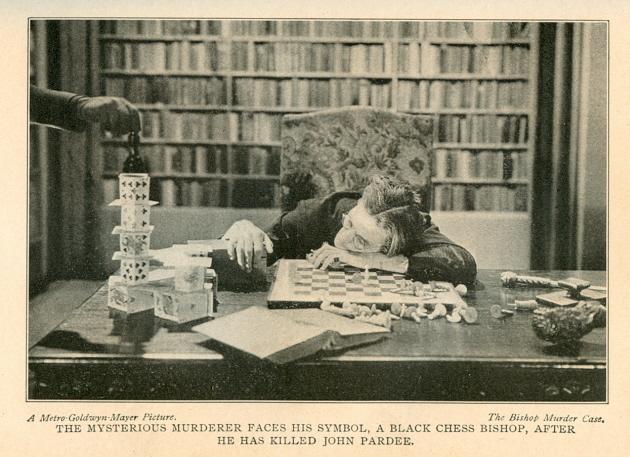

From the above-mentioned edition of van Dine’s book comes this picture:

(5948)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) sends a cutting from page 14 of La Capital, 7 November 1930:

The caption states that two Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer directors, David Burton and Nick Grinde, are discussing scenes from a film. We note that the two men co-directed the 1930 production The Bishop Murder Case (see C.N. 5948 above).

(6099)

Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA) writes:

‘A photograph showing Basil Rathbone, David Burton and Nick Grinde gathered around the same board as in C.N. 6099 appears on page 261 of the May 1979 issue of Chess Life & Review with the following caption:

“Basil Rathbone, before his series of film portrayals of Sherlock Holmes, with crew members discussing a scene in The Bishop Murder Case, in which he played supersleuth Philo Vance.”

It comes in an article entitled “Chess in the Cinema: Films of the Thirties”, one of a series of articles by Frank Brady which appeared in the magazine in 1979, and it discusses the film in some detail.’

(6105)

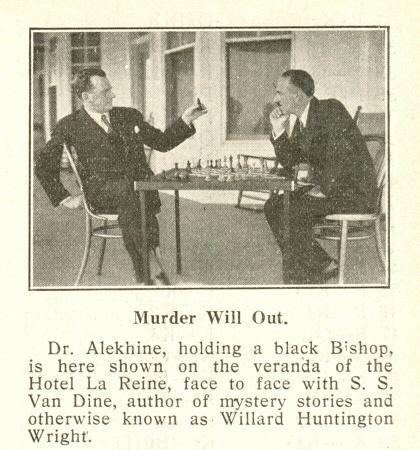

A photograph of Alekhine with the novelist was given in C.N. 5126 from page 129 of the July-August 1929 American Chess Bulletin:

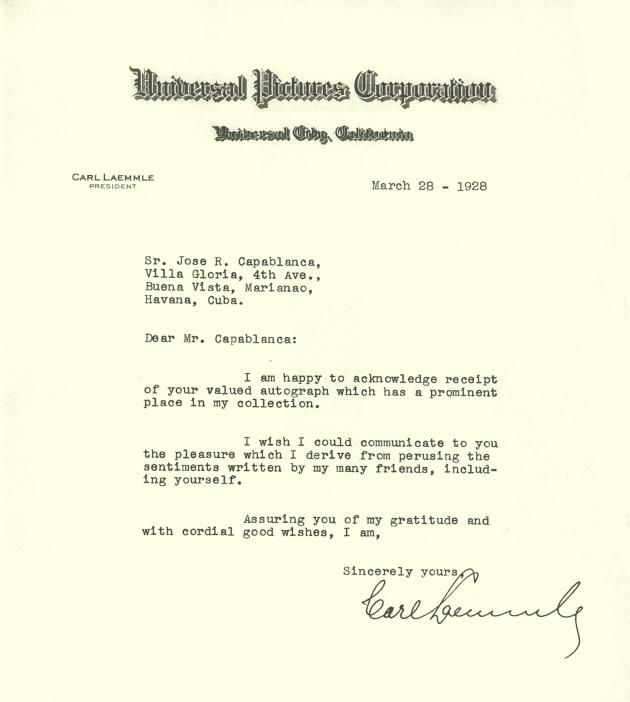

Our collection includes copies of many letters addressed to Capablanca, including the following:

(6133)

In the light of Nunnally Johnson’s article on the New York, 1924 tournament (C.N. 6881) we hoped to find some references to chess in The Letters of Nunnally Johnson selected and edited by Dorris Johnson and Ellen Leventhal (New York, 1981). The only (passing) mention of the game that has been found in the collection (which covers his correspondence from 1944 to 1976) is on page 249, in a letter dated 8 November 1974 from Johnson to Tom Dardis concerning F. Scott Fitzgerald:

In Hollywood, Johnson worked with and frequented a vast muster of celebrities. The photograph below, taken during the shooting of How to Marry a Millionaire (1953), features, from left to right, Nunnally Johnson, Marilyn Monroe and Jean Negulesco:

(6904)

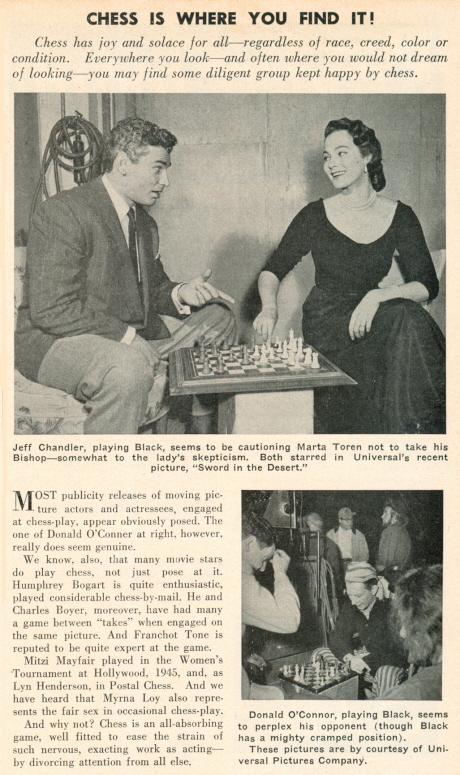

A brief article on page 97 of the April 1950 Chess Review had photographs of Jeff Chandler, Marta Toren (Märta Torén) and Donald O’Connor:

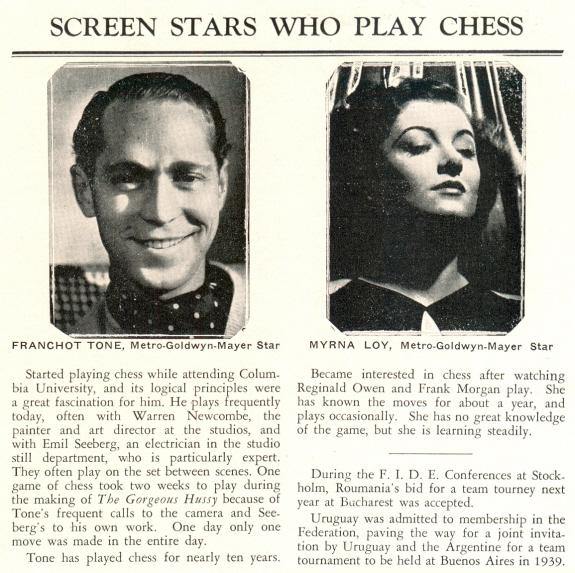

The item also referred to Franchot Tone and Myrna Loy, and we add the following from page 223 of the October 1937 Chess Review:

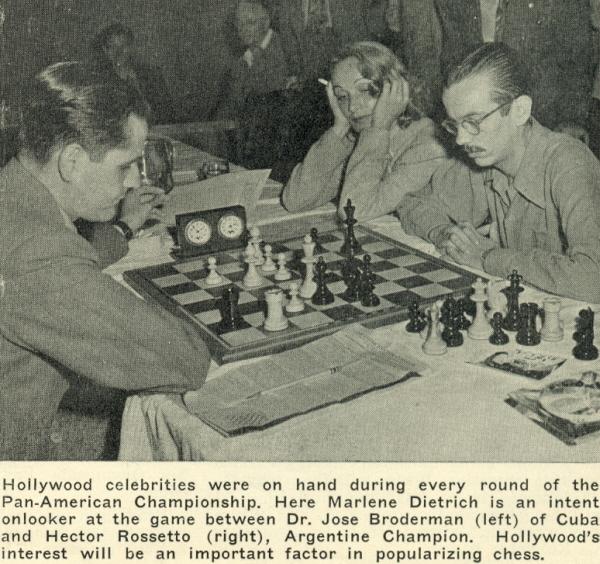

The largest pictorial feature on Hollywood and chess that we have seen is on pages 26-35 of the October 1945 Chess Review, in connection with the Pan-American Congress (won by Reshevsky ahead of Fine). The film stars included Marlene Dietrich:

The complete article is reproduced here, the illustrations being as follows:

Page 26: Barbara Bates, Dawn Kennedy, Julie London, Jean Trent.

Page 27: Reuben Fine, Carmen Miranda, J. Edward Bromberg, José Joaquín Araiza, Herbert Seidman

Page 28: Samuel Reshevsky

Page 29: Playing room

Page 30: Roseanne Murray, Herman Steiner, Samuel Reshevsky, Weaver Adams, Marlene Dietrich, José Broderman, Héctor Rossetto

Page 31: Mitzi Mayfair, Héctor Rossetto, Mary Bain, Mrs Harmath, Mrs von Sternberg, N. May Karff, Miss Roos, Linda Darnell, Roseanne Murray, Reuben Fine, Isaac Kashdan

Page 32: Al Horowitz, Fritz Lang, Nigel Bruce, Basil Rathbone

Page 33: Herman Pilnik, Samuel Reshevsky, Reuben Fine

Page 34: Living chess; Earl Carroll girls

Page 35: Barbara Hale, Bill Williams, Linda Darnell.

The photographs given above included a shot of a game of living chess in August 1945, from page 34 of the October 1945 Chess Review. Luc Winants notes that a fine version is available on-line, courtesy of the Los Angeles Times.

(7887)

Regarding the Pan-American tournament held in Hollywood in 1945, Luc Winants provides links to a number of photographs taken by Walter Sanders for Life and available on-line (using the key words chess, Sanders, 1945). Among the high-quality shots are the following:

Page 28 of the 27 August 1945 issue had a photograph of starlets playing on cubes of ice.Linda Darnell and Herman Steiner

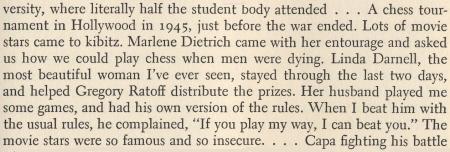

Mr Winants also notes this passage from page 211 of The World’s Great Chess Games by R. Fine (New York, 1951):

(7081)

See furthermore pages 48-49 of The World’s a Chessboard by R. Fine (Philadelphia, 1948).

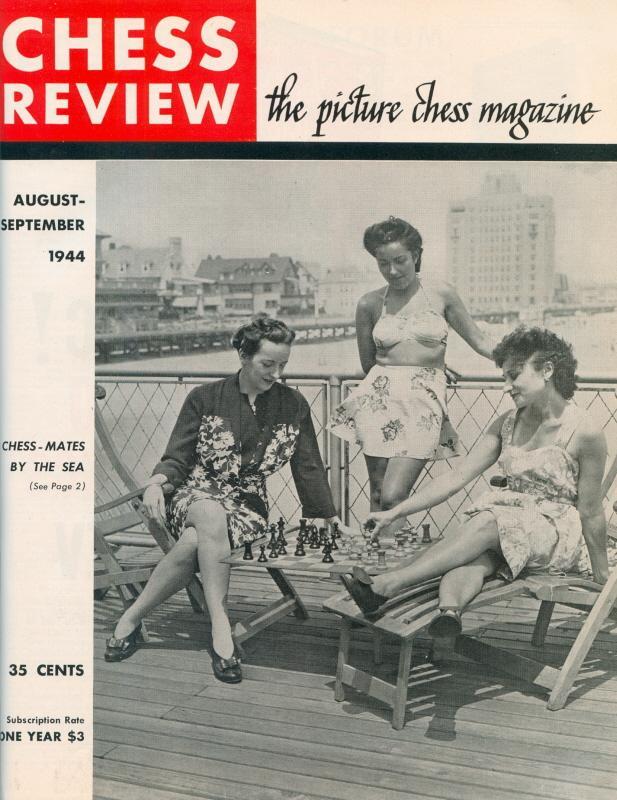

The readers’ letters section of the November 1944 Chess Review included the following from Billy Wilder:

The front cover to which he was referring:

Page 2 identified the group as comprising ‘Mrs E.S. Jackson, Jr., Mrs G. Shainswit and Mrs A.S. Pinkus, wives of three of the contestants at the Ventnor City tourney’.

(7396)

Page 185 of the July-August 1963 Chess Life had this news item in its coverage of the Piatigorsky Cup tournament in Los Angeles:

‘Most commotion of the tournament to date was caused when Frank Sinatra and Mike Romanoff walked in. Tigran Petrosian temporarily lost his title as most-stared-at individual.

The City of Hope was holding a convention at the hotel, and some of the ladies spotted Sinatra. Result – a rush to the playing room that was halted by some fast blocking on the part of our officials.’

A photograph of Sinatra with Walter Browne (and with the time-honoured ‘board problem’) was published on page 24 of Chess Life, May 1982:

(7466)

In 1927, in his pre-Hollywood phase, Alfred Hitchcock directed The Lodger, starring Ivor Novello in the title role. It had a substantial chess scene with, secondarily, substantial fodder for boardistas, boardites and boardomaniacs (the terms coined in C.N. 11471).

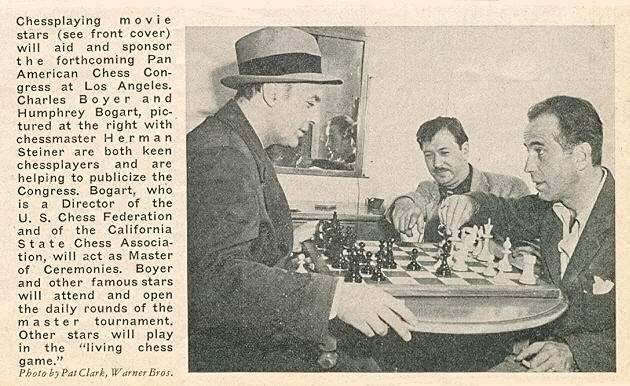

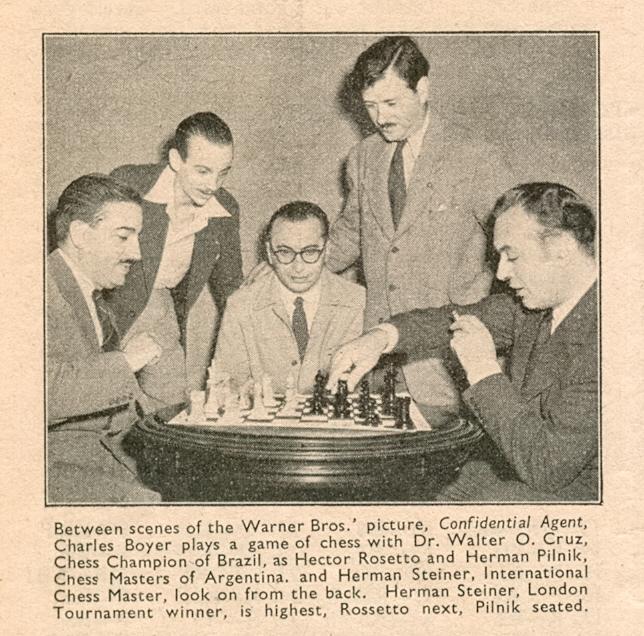

The front cover of the June-July 1945 Chess Review featured Charles Boyer, Herman Steiner, Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart:

A further photograph from page 18 of the same issue:

From page 143 of CHESS, April 1946:

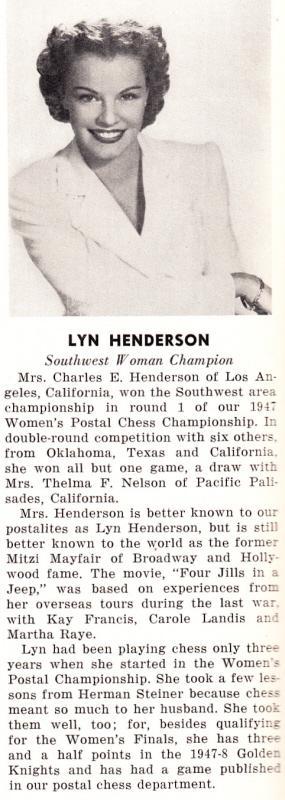

The dancer and actress Mitzi Mayfair (1914-76) was mentioned in C.N. 7076, and she appeared with Héctor Rossetto in this photograph from page 31 of the October 1945 Chess Review:

The magazine noted that she had participated in the women’s tournament in Hollywood under her married name, Mrs Charles Henderson.

Steven B. Dowd (Birmingham, AL, USA) adds that this biographical note was published on page 26 of Chess Review, November 1948:

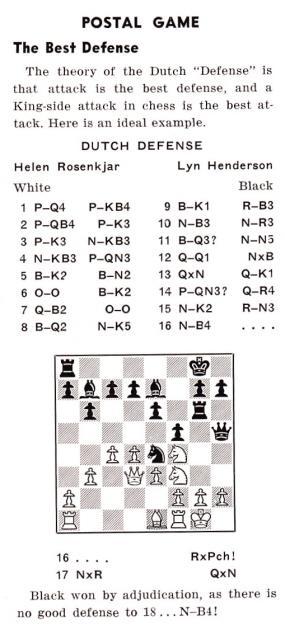

Our correspondent also points out that the game referred to was on the inside back cover of Chess Review, October 1947:

Helen Rosenkjar – Lyn Henderson

Correspondence game

Dutch Defence

1 d4 f5 2 c4 e6 3 e3 Nf6 4 Nf3 b6 5 Be2 Bb7 6 O-O Be7 7 Qc2 O-O 8 Bd2 Ne4 9 Be1 Rf6 10 Nc3 Na6 11 Bd3 Nb4 12 Qd1 Nxd3 13 Qxd3 Qe8 14 b3 Qh5 15 Ne2 Rg6 16 Nf4 Rxg2+ 17 Nxg2 Qxf3 and ‘Black won by adjudication’.

(7491)

The front-cover picture of Chess Review, October 1948:

From page 2:

‘If looks could kill, anyone facing Sid Caesar, comedy star of the hit musical Make Mine Manhattan, would die laughing. On the other hand, perhaps the wholesome beauty of Barbara Weaver, also a member of the company, offsets Caesar’s hilarious mugging.’

(7507)

Steven B. Dowd asks what grounds there may be for a statement at the IMDb website regarding the actor George Mathews (1911-84):

‘In private life, Mathews was the antithesis of the ruffians he often portrayed on screen: amicable and intelligent. Outside of his profession, he was an avid chessplayer and often participated in international tournaments.’

(8041)

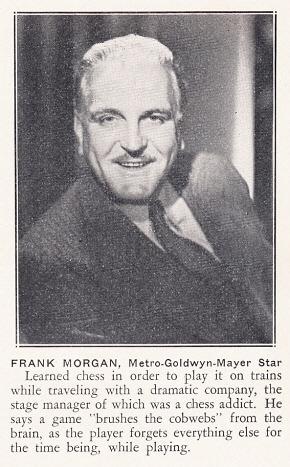

A small feature on Frank Morgan from page 2 of the January 1938 Chess Review:

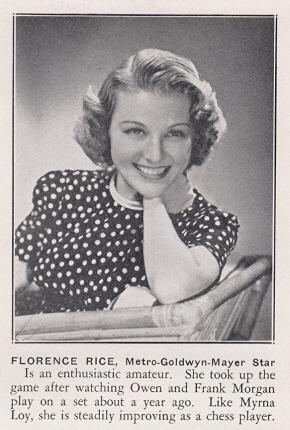

Florence Rice appeared on page 291 of the December 1937 Chess Review:

From our collection, a photograph of Maximilian Schell, in Return from the Ashes:

Concerning the alleged game between Paul Limbos and Humphrey Bogart, see C.N. 8536.

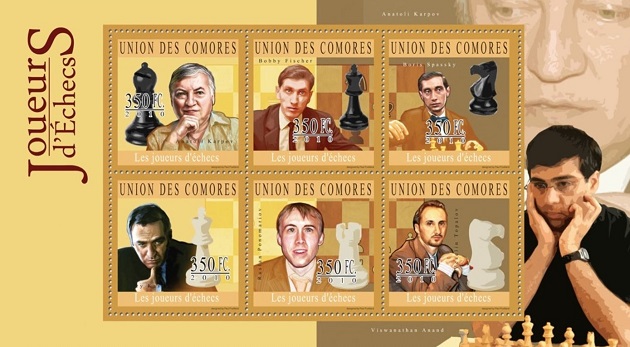

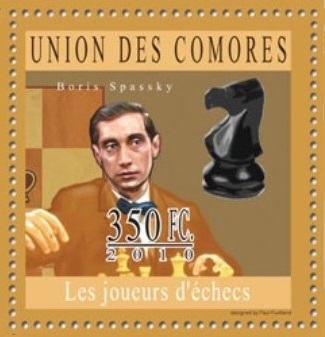

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada) draws attention to a set of postage stamps:

Our correspondent notes that ‘Boris Spassky’ is Vladek Sheybal, who played the role of Kronsteen in the 1963 film From Russia with Love.

(9658)

From the ‘Problem Pages’ column by P.H. Williams on page 11 of the Chess Amateur, October 1919:

The poster for the film may be viewed on-line.

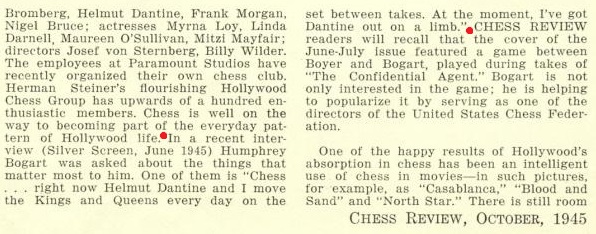

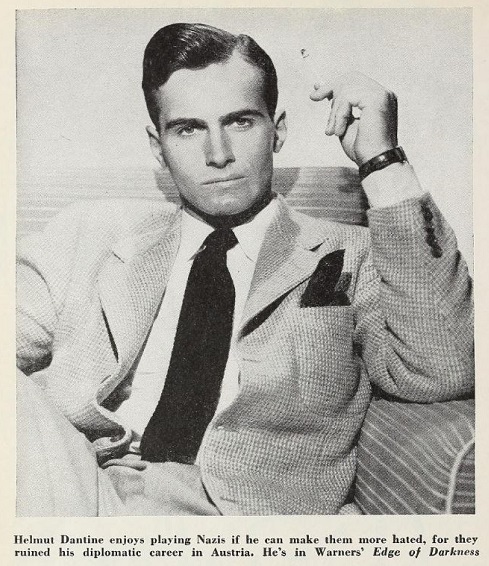

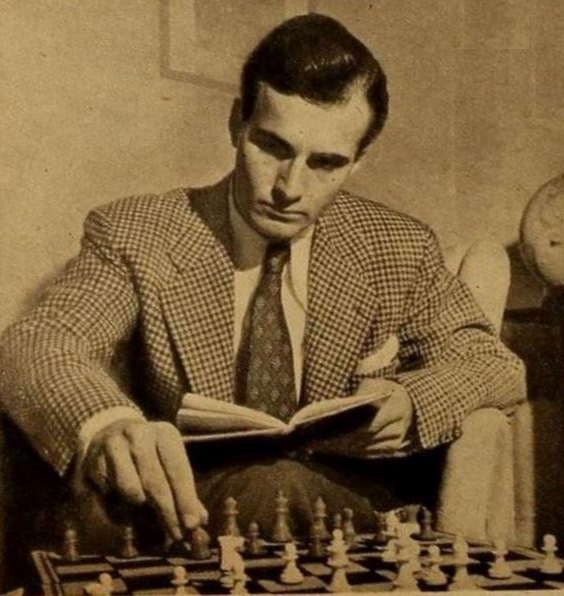

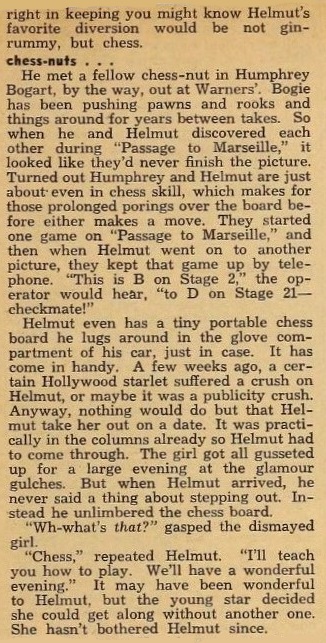

C.N. 7076 had a reference to Helmut Dantine (1918-82) from page 26 of the October 1945 Chess Review:

Olimpiu G. Urcan provides some further material on the actor:

1) On page 36 of Hollywood, January 1943, Dorothy Haas wrote about Dantine:

‘In addition to writing, his real hobby is chess. He and Humphrey Bogart played every day during the shooting of Casablanca. He likes all active sports and enjoys watching football and baseball.’

The accompanying photograph:

Bogart and Dantine in Casablanca:

2) From the Long Beach Independent, 4 July 1943, page 16:

‘Helmut Dantine, featured in Warner Bros’ Edge of Darkness, has entered the National Association Chess tourney. Helmut was seventh-ranking player in Vienna.’

3) Modern Screen, June 1944, page 38 had this:

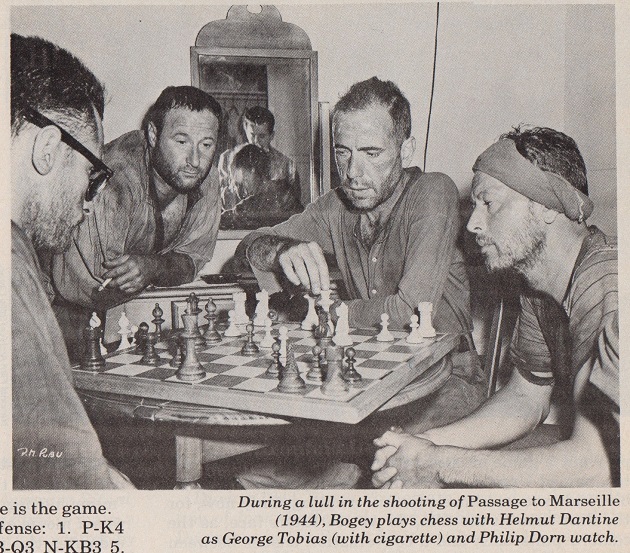

Dantine’s role in Passage to Marseille was featured on page 56 of the same issue of Modern Screen, with this photograph:

From page 91 (text by Jack Carson):

4) A photograph of Dantine and Bogart at the chessboard, with George Tobias and Philip Dorn, was on page 12 of the 14 January 1944 edition of the Salt Lake Tribune. As shown below, it also appeared on page 393 of Chess Life & Review, July 1979:

5) From the Olean Times Herald, 27 December 1949, page 7 (and in other newspapers in late December 1949):

‘Helmut Dantine’s prowess at chess makes him puffier than any critics’ praises he ever won at acting. Whenever he’s in New York he can be found haunting the midtown chess parlors, and he’s never so happy as when one of the gray-bearded experts takes him on for a contest. His mail-box gets crammed with communiqués from other chess addicts, and he always has a dozen chess-by-mail opponents following wherever he may travel.’

(10495)

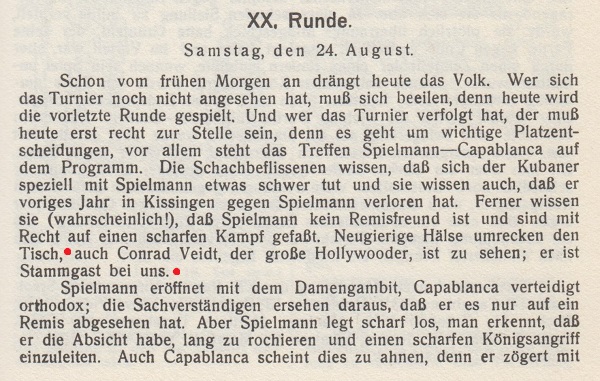

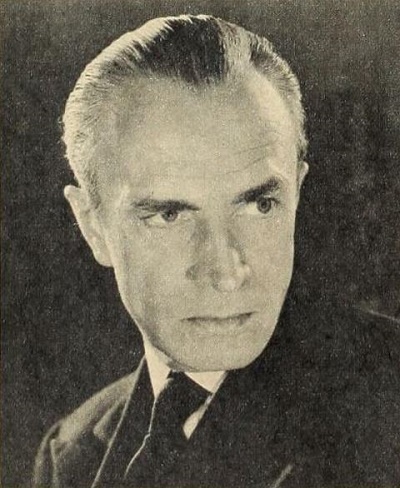

Mention of Casablanca in the item on Helmut Dantine (C.N. 10495) prompts Edward Hamelrath (Dresden, Germany) to point out a reference to Conrad Veidt on page 379 of the Carlsbad, 1929 tournament book:

Conrad Veidt, Hollywood, February 1943, page 32

Chess in the Movies by Bob Basalla (C.N. 3986) mentions in connection with Veidt A Man’s Past (1927), Le joueur d’échecs (1938) and The Thief of Bagdad (1940).

In Le joueur d’échecs Veidt played the role of von Kempelen. Below are two photographs from the Sketch, 22 June 1938, page 599:

(10499)

Olimpiu G. Urcan has provided this still from The Thief of Bagdad:

Ed Hamelrath draws attention to a webpage with many behind-the-scenes photographs taken during the production of Casablanca, including (fifth from the bottom) a shot of Humphrey Bogart playing chess against Paul Henreid.

(10612)

Chess Review, February 1954, page 38

Page 200 of Chess in the Movies by Bob Basalla (Davenport, 2005) identified Robert Taylor’s opponent as Ava Gardner, instead of Maureen Swanson, in this film, Knights of the Round Table.

(11261)

Olimpiu G. Urcan has acquired permission from Mondadori for us to reproduce a photograph taken during the shooting of the 1967 film A Countess from Hong Kong:

Marlon Brando, Charlie Chaplin, Sophia Loren

(11405)

Concerning the 1930 film the 1930 production The Bishop Murder Case, see The Single Bishop Mate.

A photograph of Douglas Fairbanks, Jr playing chess against Harry Borochow was published on page 2 of Chess Life, 5 May 1959.

Many chessplayers are sticklers for fact only regarding works of fiction.

Addition on 11 March 2024:

The Bogoljubow v Trott game is used, with colours reversed, in the 2023 animated short film War Is Over! directed by Dave Mullins and co-written by him and Sean Ono Lennon. We proposed the 1950 game to him when he requested an illustration of the theme of check followed by immediate checkmate.

A still from War Is Over! (reproduced with permission)

At the Academy Awards ceremony in Los Angeles on 10 March 2024, War Is Over! won the Oscar in the category ‘Best Animated Short Film’.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.