Edward Winter

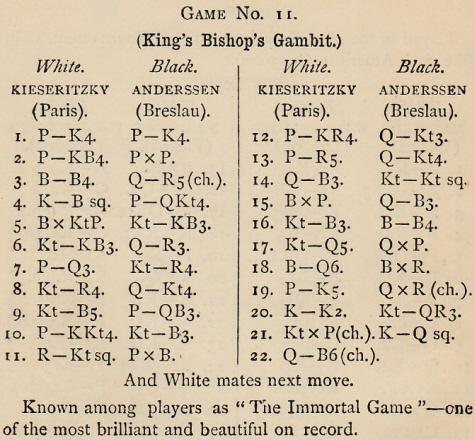

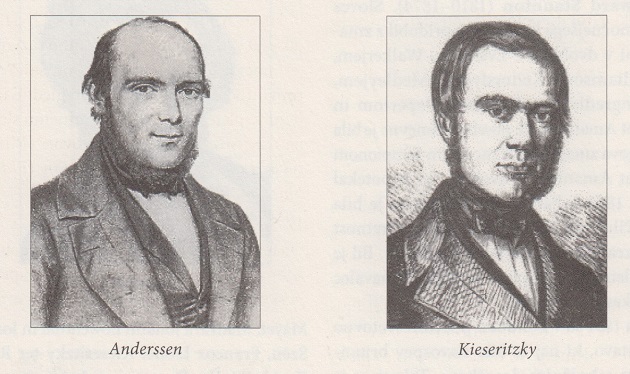

No blunder is too elementary to have been made by chess writers at one time or another. R.F. Green’s book Chess (page number varies in different editions) and C.B. Rogers’ How to Play Chess (pages 155-156) both gave the ‘Immortal Game’ as having been won by Kieseritzky against Anderssen.

(2469)

When the above item was included on page 314 of A Chess Omnibus we added in a footnote that another instance was page 45 of Chess and Draughts by Albert Belasco (various editions).

Before us lies a modern reprint of R.F. Green’s 1889 book Chess, brought out by the Tynron Press, Stenhouse in 1990. Slothful, uninformed duplicators posing as publishers were referred to in C.N. 3586, and here is another instance. The reprint even perpetuates Green’s blunder (on page 108) of stating that in the Immortal Game Kieseritzky defeated Anderssen.

(5464)

From our collection:

A report on the display, by Antonio Maspoli, was published on pages 164-165 of the September 1968 Schweizerische Schachzeitung.

(7983)

Regarding The Immortal Game by David Shenk (New York, 2006) see C.N. 8110.

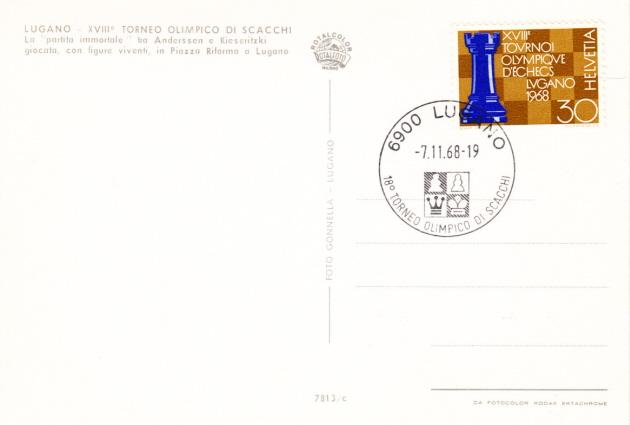

Below is the billing for Samuel Tinsley’s talk on chess (British Broadcasting Company, Saturday evening, 23 January 1926) in the programme schedule on page 157 of the Radio Times, 15 January 1926:

‘S.B.’ means simultaneous broadcast.

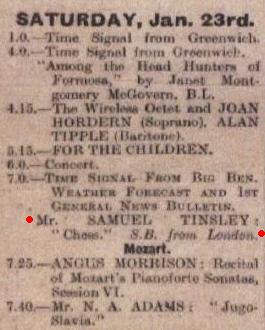

As shown in C.N. 8725, Tinsley mentioned in his talk that the Anderssen v Kieseritzky ‘Immortal Game’ was published in the same issue of the Radio Times. From page 148:

Permission to show the above material has been received from Immediate Media Company London Limited, the publishers of the Radio Times.

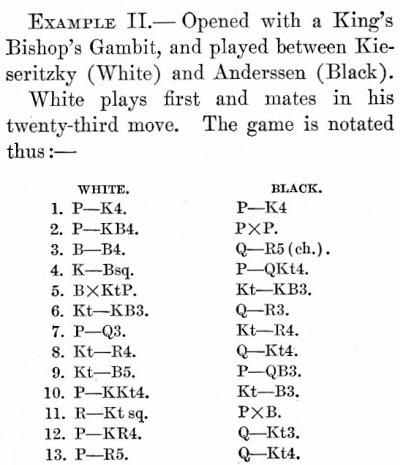

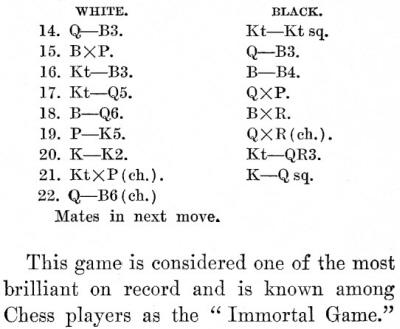

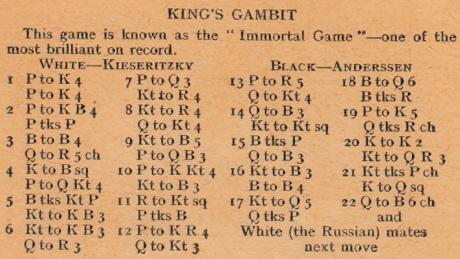

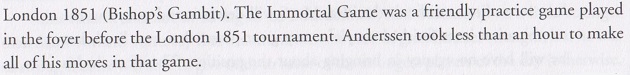

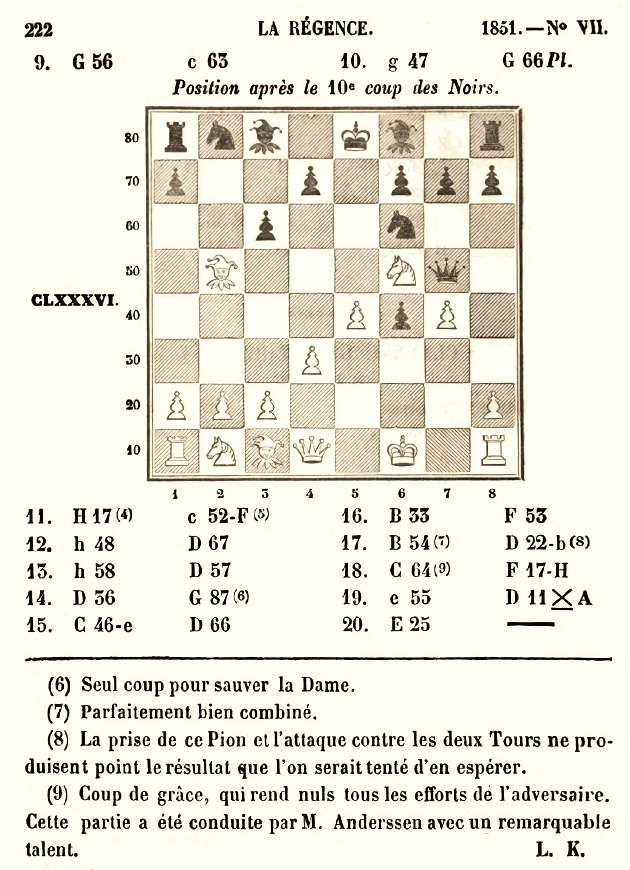

It has been shown that the ‘immortal games’ won by Nimzowitsch and Najdorf were not widely published at first. The same applies to the Immortal Game between Anderssen and Kieseritzky, although the loser did give it, with praise for Anderssen, on pages 221-222 of La Régence, July 1851.

Can readers help us to draw up a list of the game’s appearances in print in the mid-nineteenth century?

As mentioned in C.N. 2469, some books have inexplicably stated that Kieseritzky won. Below are the three cases referred to on page 314 of A Chess Omnibus:

Chess by R.F. Green (various editions)

Pages 155-156 of How to Play Chess by Charlotte Boardman Rogers (New York, 1907)

Page 45 of Chess & Draughts by Albert Belasco (various editions).

C.N. 1965 (see page 270 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) noted that the 1930s book Chess and How to Play It by B. Scriven correctly identified Anderssen as the winner but made a peculiar claim about the occasion of the game:

(8854)

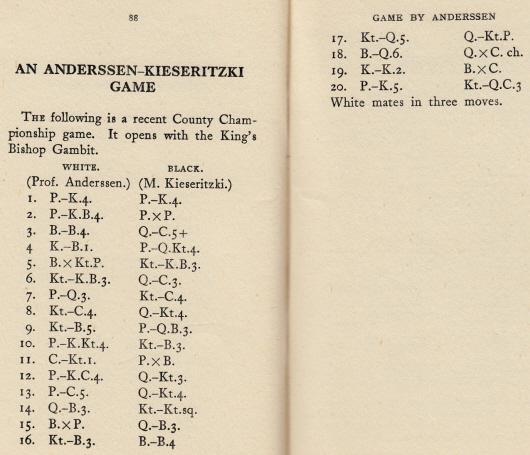

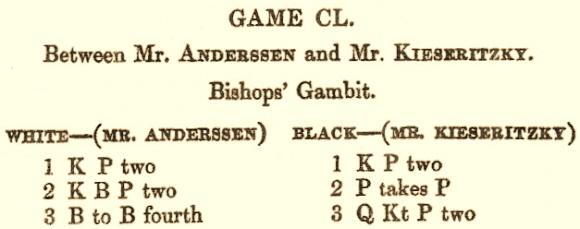

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) also mentions that the Immortal Game was published on pages 171-172 of Horæ Divanianæ by Elijah Williams (London, 1852):

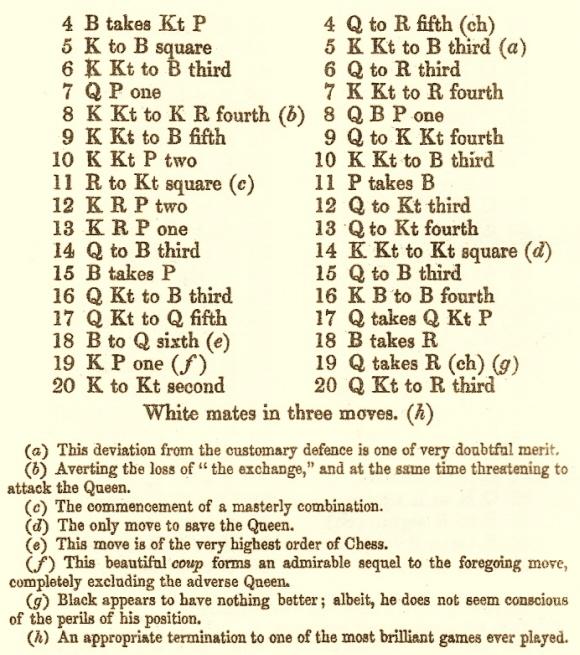

Our correspondent furthermore points out a remark on page 274 of The Game of Chess by George Selkirk (London, 1868):

(8862)

For information about the ‘Bryan Counter-Gambit’ (...b5) see C.N. 9045.

C.N. 9444 quoted from a tribute to Anderssen by Steinitz on page 362 of The Field, 29 March 1879 which included the following:

‘... no living player can boast of such a grand record of numerous triumphant victories in tournaments as have been achieved by Anderssen. Nor had he his peer as regards elegance and brilliancy of style; and some of his games, like those published below [the Immortal Game and the Evergreen Game], will ever be regarded as amongst the finest specimens of bold and surprising chess tactics, combining beauty of conception with depth of design.’

Our item added that Steinitz’s notes to the Immortal Game included the following after 18 Bd6:

‘This and the rest of Anderssen’s conduct of the attack mark the limit of ingenuity and brilliancy exhibited in the actual contest up to our time.’

The concluding observation by Steinitz on the Anderssen v Kieseritzky game:

‘In memoriam of Anderssen, the present masterpiece will be treasured as an example of chess genius as long as the game shall be played.’

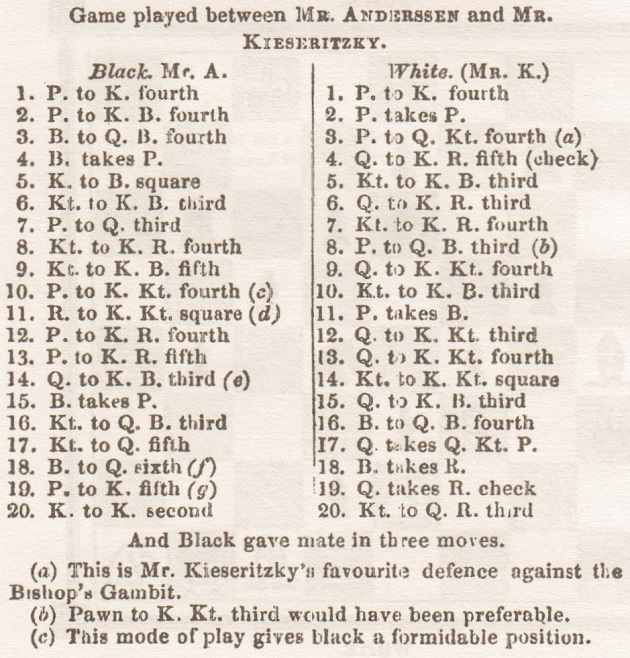

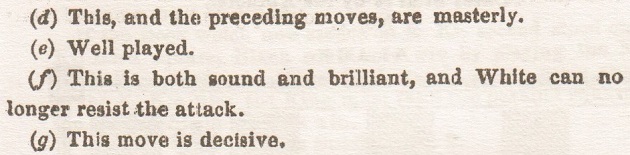

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) notes that the game was published on pages 2-3 of the Chess Player (edited by Kling and Horwitz), 19 July 1851, with the first player indicated as having the black pieces (as was often the practice at the time):

Our correspondent adds that when the game appeared in Bell’s Life in London, 28 November 1852, page 5, there was an acknowledgement to the Chess Player, but Anderssen was said to have played with the white pieces:

C.N. 10067 pointed out that towards the end of ¿Juguemos al ajedrez? (Barcelona, 1947) – the pages are unnumbered – the Immortal Game was shown, with Anderssen’s nationality given as English, and his opponent misnamed (‘... entre los grandes maestros Anderssen (inglés) y Kiesevitzki (ruso)’). The same mistakes occur in connection with the musical composition La Inmortal by Ferrer Ferran.

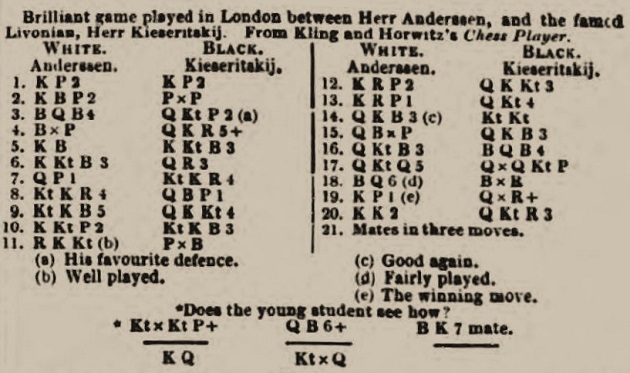

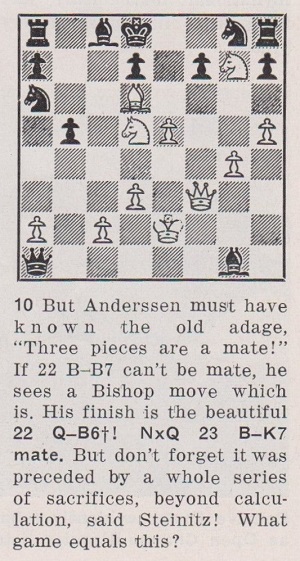

The final diagram in the presentation of the Immortal Game between Anderssen and Kieseritzky on page 297 of the October 1959 Chess Review:

The literal implication that the adage ‘three pieces are a mate’ pre-dated 1851 can be discarded, but who first made the observation?

On page 28 of The Seven Deadly Chess Sins (London, 2000) J. Rowson described ‘three pieces is a mate’ as ‘Tartakower’s claim’. On page 606 of Chess Life & Review, November 1970 A. Soltis wrote, ‘... as Tartakower said, “three pieces are a mate”.’

Introducing a correspondence game between Krozel and Thompson on page 224 of the July 1955 Chess Review John W. Collins wrote: ‘A short game which further demonstrates that three pieces are a mate.’ An editorial footnote on page 369 of the December 1964 issue stated: ‘As the late Henry Eckstrom would have said: “Three pieces are a mate”.’

(10252)

Emanuel Lasker’s view of the Immortal Game:

‘It is not very difficult to understand why the “Immortal Game” between Anderssen and Kieseritzky should appeal to the popular mind. Besides the enormous sacrifice of material by White, there is the rare occurrence of all Black’s pieces on the board when he is mated.

The effect of the tremendous labor of the annotators of this game must ultimately result in removing it from the singularly high position in which it has been fixed. The demonstrable fact that White missed a certain win, and that later Black missed a certain draw, practically removes the game from the realms of the classics.

It is a very moot question whether “skittle” games deserve the amount of attention which is bestowed upon them. It may be that irresponsibility and accident produce bewildering, dazzling and even original positions.

“Skittle” playing, as recreation, has a useful function to perform. But, if chess is to be treated as literature, then it is incumbent that the games that are published shall be the product of much thought, of deep imagination, of a sentiment of truth; and above all that the players shall be imbued with a feeling of responsibility, such as follows from tournament or match play.’

The game was then given with detailed notes.

Source: pages 18-20 of the Chess Player’s Scrap Book, February 1907. The periodical, edited by Lasker, was discontinued later that year, after issue 6-7.

(10502)

The Immortal Game and the Evergreen Game were annotated on pages 82-84 of Emanuel Lasker’s London Chess Fortnightly, 14 January 1893.

An inscription by Al Horowitz in one of our copies of his book How to Win in the Middle Game of Chess (New York, 1955):

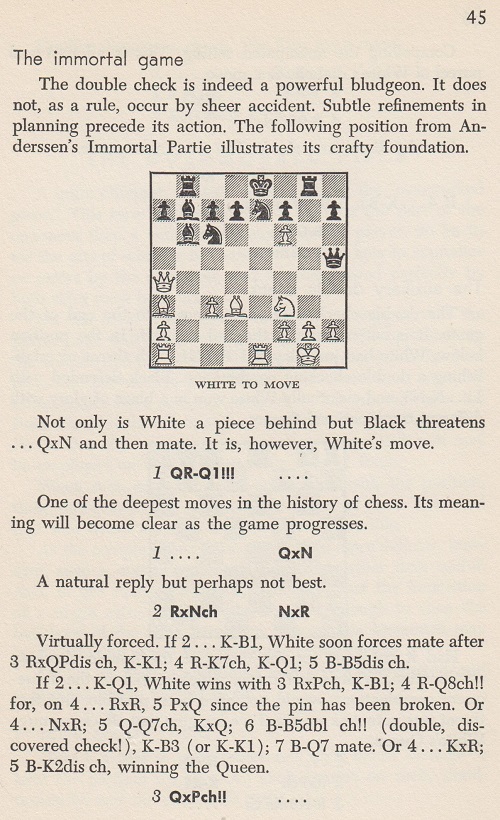

From pages 45-46:

On page 202 of the July 1953 Chess Review Horowitz had given the same material, also mistitled ‘The Immortal Game’.

(10566)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) draws our attention to his review of the e-book Carlsen v Caruana: FIDE World Chess Championship, London 2018 by Raymond Keene and Byron Jacobs (London, 2018) and sends us half a dozen lines from the book’s ‘History of the World Championship’ section:

We offer a few comments:

Even without primary sources, a quick glance at, for instance, The Oxford Companion to Chess by D. Hooper and K. Whyld (Oxford, 1992) would have sufficed to avoid all these elementary blunders.

(11126)

Concerning Raymond Keene’s affirmation that the Immortal Game was played at Simpson’s in London, see C.N.s 11357 and 11364 below.

C.N. 11254 gave, under the heading ‘Anderssen and Anderssen’, the following from page 14 of Veliki šahovski turnirji 1851-1911 by Janez Stupica (Ljubljana, 2013):

Some more snippets:

Chess Words of Wisdom by Mike Henebry (Victorville, 2010), page 346

The World of Chess by Anthony Saidy and Norman Lessing (New York, 1974), page 86

Chess An Illustrated History by Raymond Keene (Oxford, 1990), page 48

Championship Chess and Checkers for All by Larry Evans and Tom Wiswell (New York, 1953), page 49

Chess Life, May 1996, page 15 (a reply in the ‘Evans on Chess’ column).

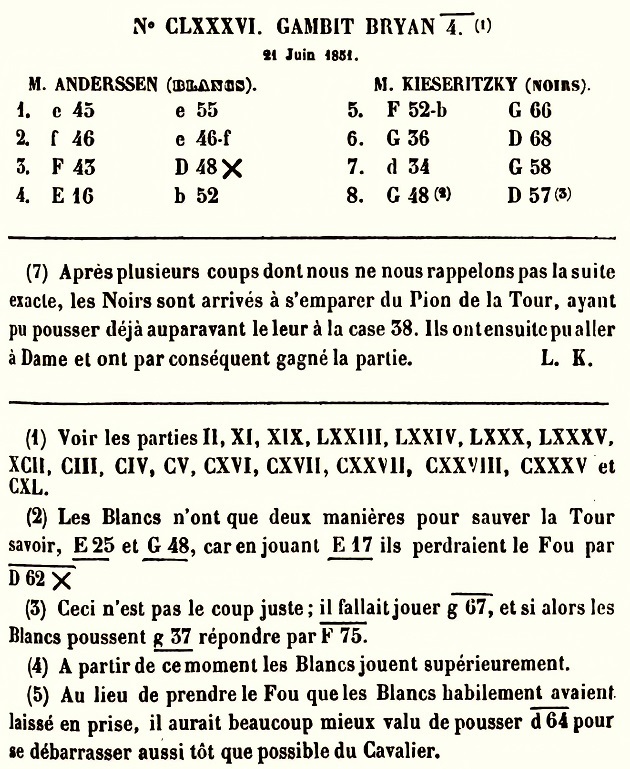

Our feature article shows that according to page 221 of La Régence, July 1851 the Anderssen v Kieseritzky brilliancy was played in London on 21 June 1851. Now, though, Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy) draws attention to this passage on page 482 of volume two of the Baltische Schachblätter:

‘Die unsterbliche Partie. Diese wurde zwischen Anderssen und Kieseritzky in London am 13. (25.) Mai 1851 gespielt.’

A related footnote on the same page added:

‘Diese genauere und richtigere Datumangabe beruht darauf, dass die Partie im St. George-Club am Tage vor der Eröffnung des grossen Londoner Schachturniers gespielt wurde.’

Mr Zavatarelli comments that the writer, F. Amelung, had detailed knowledge of Kieseritzky, having published an article about him on pages 55-87 of the first volume of Baltische Schachblätter (1890) which included 16 letters, or excerpts therefrom, written by Kieseritzky.

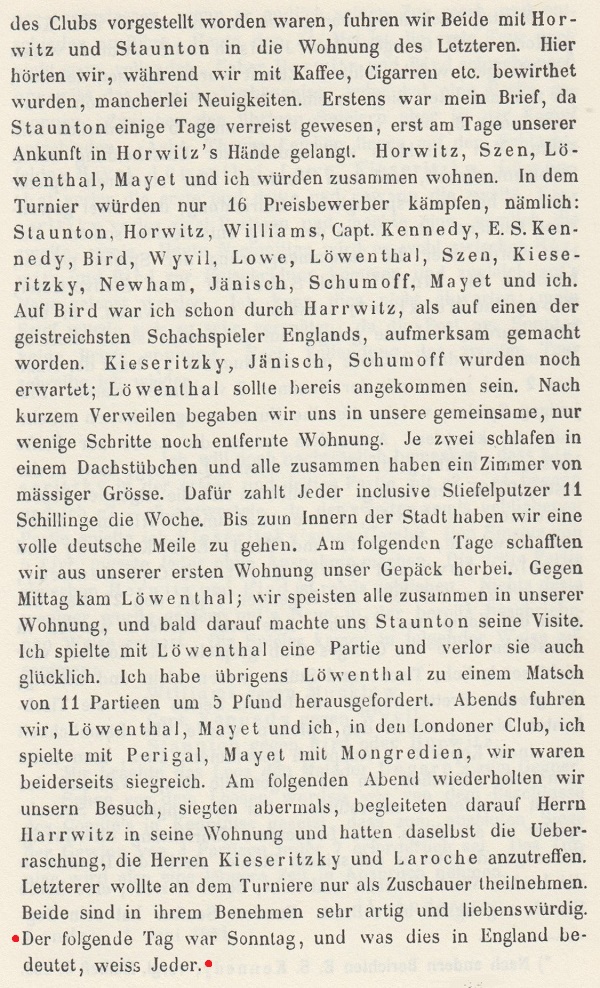

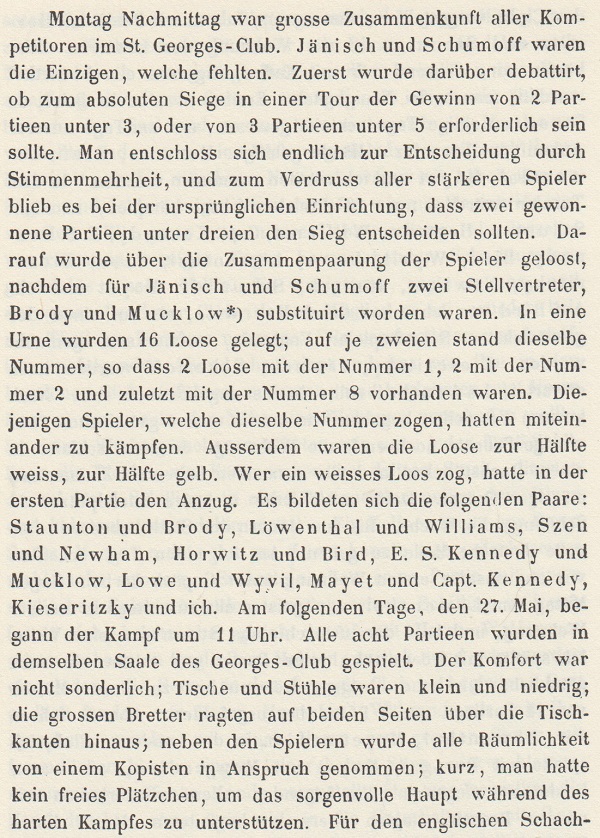

Play in the London tournament began on Tuesday, 27 May 1851, the pairings having been made the previous day (Deutsche Schachzeitung, May, 1851, pages 163-164).

Our correspondent adds that Anderssen wrote an account of his journey to London (a letter dated 1 June 1851) on pages 165-169 of the June-July 1851 Deutsche Schachzeitung. It began:

‘Donnerstag, den 22. Mai, als eben der Morgen grauete, traf ich auf dem Dampfboot, das mich nach England übersetzte, mit Mayet zusammen ...’

Anderssen’s only mention of 25 May, at the bottom of page 167, carried the implication that, being Sunday, it was a day of rest:

(11357)

Concerning the date and venue of the Immortal Game, John Townsend writes:

‘In C.N. 11357 Anderssen was quoted as indicating that Sunday was a day of rest in England. Gliddon’s (42 King Street, Covent Garden, London) was open for chess on Sundays according to an article by Alphonse Delannoy in Le Palamède, December 1845, page 559:

“Le second (Clydon [sic] Coffee House, Covent-Garden) jouit d’un privilège bien rare en Angleterre, celui de laisser jouer le dimanche.

C’est là que se rendent alors tous les amateurs que n’effraie pas l’excommunication anglaise ...”

Delannoy added that London players, including members of St George’s Chess Club, had a weekly gathering at Gliddon’s on Sundays:

“Au Clydon Coffee House se confondent alors les membres du Cavendish Square, du Grand Cigar’s Divan et du London’s Chess Club. Là se déroulent les événemens de la semaine, là s’enregistrent les bulletins de victoires et les tristes défaites. L’aristocratie du Cavendish Square descend à la familiarité du London’s Chess Club, et cette réunion ne manque pas d’intérêt.”

However, it seems improbable that Gliddon’s was the venue for the Immortal Game, and not least because Anderssen’s report mentioned no visit there. If the game was indeed played on 25 May, it cannot be excluded that the venue was one of the players’ lodgings.

The Baltische Schachblätter footnote cited in C.N. 11357 stated that the game was played at the St George’s Chess Club the day before the opening of the London tournament. Play in that event began on Tuesday, 27 May, and page lxiii of Staunton’s tournament book reported:

“The 26th of May, 1851, was the day appointed by the Committee of Management for the assemblage of all those who proposed to take part in the general mêlée. The appointment was punctually observed by most of the foreign players whom we had expected to be present at the Congress.”

Anderssen and Kieseritzky were required to attend at St George’s Chess Club on that day, when the “balloting for opponents” took place (page lxiv of the tournament book). Whether or not there was time for a few casual games has not been ascertained. As chance would have it, Anderssen and Kieseritzky were paired together for the first round.

Since the footnote cited in C.N. 11357 could mean that the date was 26, and not 25, May and since it also identifies the venue as the St George’s Chess Club, there are grounds for deducing that the Immortal Game was, in fact, played on Monday, 26 May, notwithstanding the dates (25 May and 21 June) given, respectively, in the Baltische Schachblätter and La Régence.’

We add below Anderssen’s account of the proceedings on Monday, 26 May from page 168 of the June-July 1851 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

What corroboration exists of the common assertion that the Immortal Game was played at Simpson’s Divan?

Another question is when, and by whom, the Anderssen v Kieseritzky brilliancy was first named ‘the Immortal Game’. The entry on page 192 of the Dictionnaire des échecs by François Le Lionnais and Ernst Maget (Paris, 1967) named Philipp Hirschfeld (and incorrectly stated that Kieseritzky did not take part in the London, 1851 tournament):

Page 277 of the Dizionario enciclopedico degli scacchi by Adriano Chicco and Giorgio Porreca (Milan, 1971) asserted that Falkbeer was the first to use the ‘Immortal’ name:

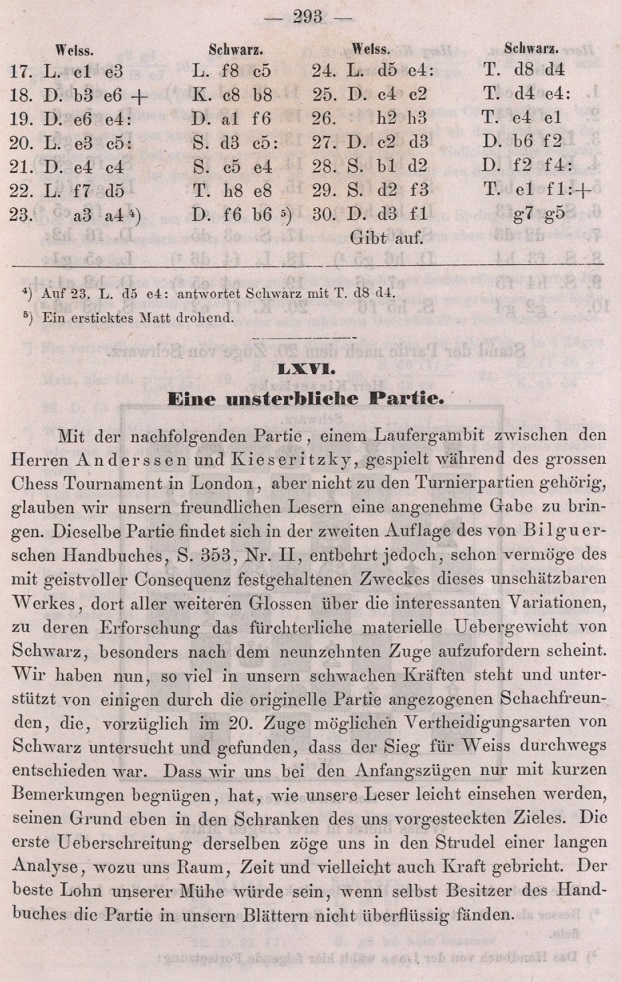

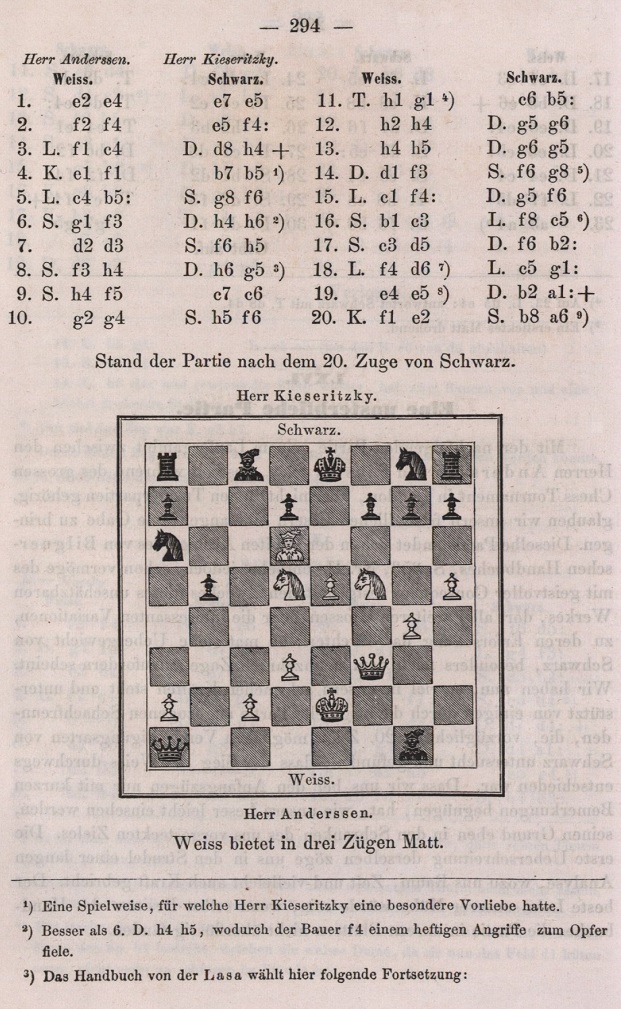

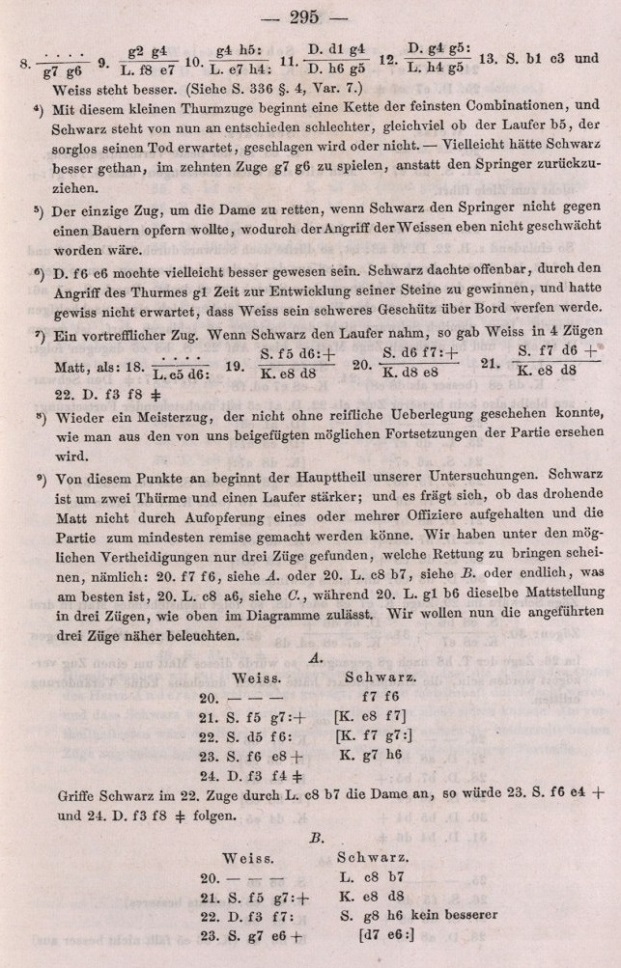

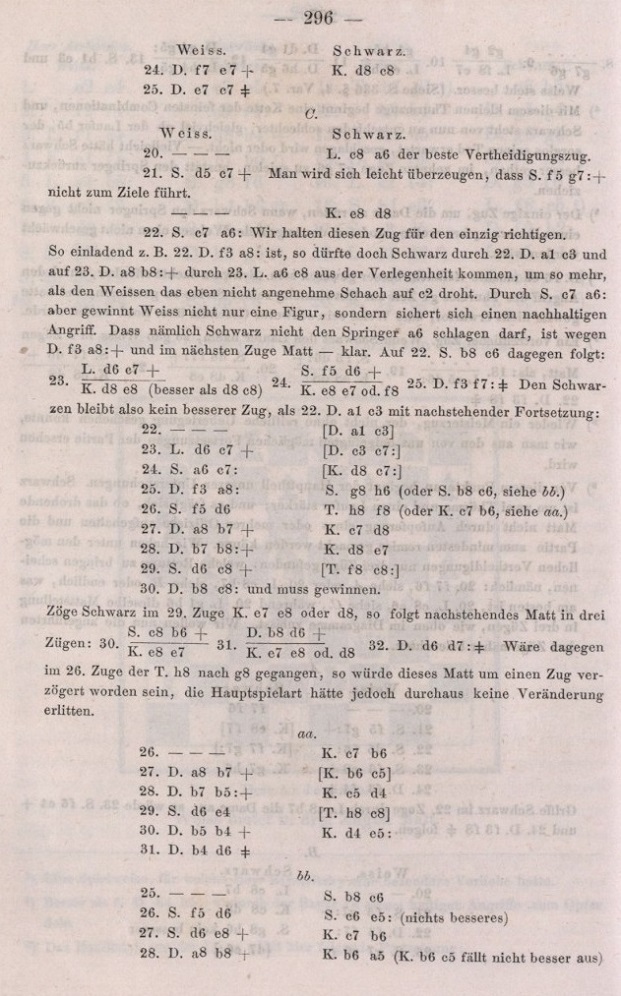

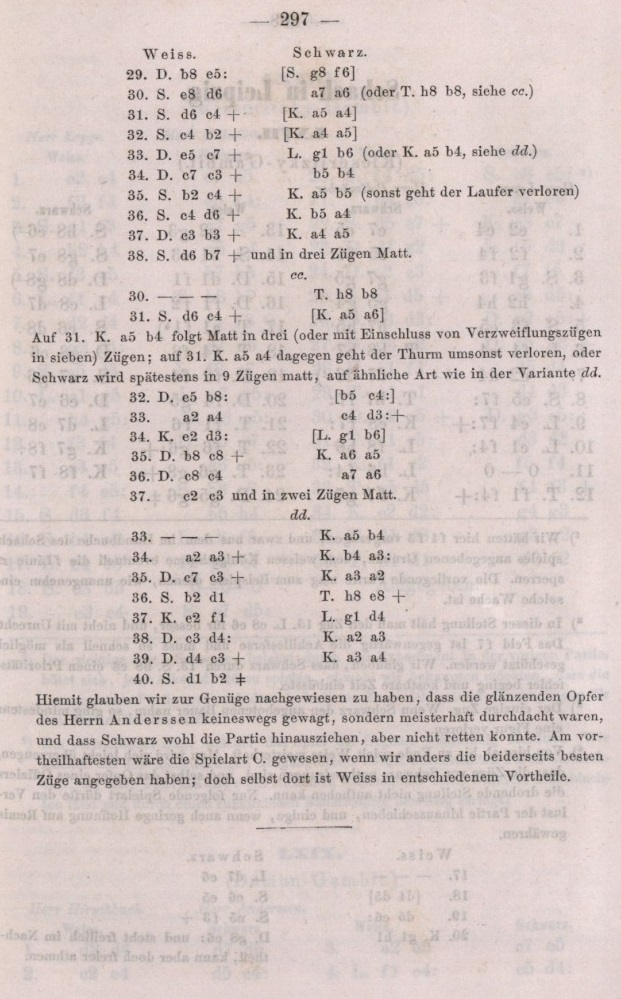

Regarding that reference to Falkbeer, below is an unsigned article on pages 293-297 of the August 1855 issue of his Wiener Schach-Zeitung:

(11364)

Addition on 1 June 2021:

C.N. 8862 reproduced the Immortal Game’s appearance on pages 171-172 of Horæ Divanianæ by Elijah Williams (London, 1852), and John Townsend now wonders to what extent that may be regarded as evidence that the Divan was the venue. The matter is not clear-cut because the title-page states that the work is an anthology of games ‘principally’ played at the Grand Divan, and the book does not specify which games were, at least in Williams’ belief, played elsewhere.

Mr Townsend adds Staunton’s comments about Horæ Divanianæ in the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1852, page 281:

‘We have one capital game between Kieseritzky and Anderssen, and an odd game won by Mr Bird of Mr Anderssen! But we look in vain for the games which were played at the Divan between Anderssen and Löwenthal, between Szén and Laroche, and the rest of the games between Anderssen and Kieseritzky, besides many others.’

More generally, further evidence is sought regarding the Immortal Game’s appearance in mid-nineteenth-century sources – including publications in German and French, and not only English – and not least regarding variants in the game-score.

There is no consensus over the exact concluding moves of the Immortal Game. On pages 221-222 of La Régence, July 1851 Kieseritzky himself stated that the finish was 19 e5 Qxa1+ 20 Ke2:

Note 7 on page 221 relates to a previous game in the magazine.

(11381)

In his article ‘The Romantic Art in Chess’ on pages 15-16 of the January 1969 Chess Life, Pal Benko discussed the Immortal Game and The Immortal Chess Problem.

(11423)

Under the heading ‘An “Immortal” Comes Unstuck’ C.J.S. Purdy asserted on page 175 of Chess World, August 1961:

‘In chess talk, an “immortal” simply means a game where you give up both rooks. In the original one, Anderssen-Kieseritzky, Anderssen gave his queen also.’

The game annotated by Purdy, between P.J. Viner and W.J. Geuse, occurred on board six in a match between Victoria and New South Wales played on 21 October 1960 by teletype: 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Bb4 5 e5 h6 6 Bd2 Bxc3 7 bxc3 Ne4 8 Bc1 c5 9 Bd3 Nxc3 10 Qg4 g6 11 Nf3 c4 12 Bxg6 fxg6 13 Qxg6+ Kd7 14 Qg7+ Kc6 15 Bxh6 Ne4 16 h4 Rg8 17 Qf7 Rxg2 18 Bg5 Qa5+ 19 Bd2 Nxd2 20 Nxd2 Qc3 21 Qf8 Qxa1+ 22 Ke2 Qxh1 23 Qxc8+ Kb6 24 Qc5+ Ka6 25 Qa3+ Kb5 26 Qc5+ Ka4 27 Nxc4 Rxf2+ 28 Kxf2 Qxh4+ 29 Ke2 Qg4+ 30 Kf2 Qf4+ 31 Kg2 Qe4+ 32 Kg3 Qe1+ 33 Kg4 Qe2+ 34 Kg5 Qxc4 35 White resigns.

John Townsend writes:

‘A “Certificate of Arrival” at the port of Folkestone shows that Kieseritzky arrived there on 24 May 1851 (source: National Archives, HO 2/212, certificate no. 1067), this being a document which, with many others similar, is viewable on-line at Ancestry.com.

Under the heading “Name and country” is entered: “Mr Lionel Kieseritzki [sic] Russia”. The country from which he had last arrived was France and he had a passport from the French government. The certificate bears a good specimen of his signature: “L. Kieseritzky”.

As a result of Fabrizio Zavatarelli’s discovery in Baltische Schachblätter (reported in C.N. 11357), the Chess Notes feature article on the Immortal Game subsequently considered two dates, 25 and 26 May, as days when the celebrated game may have been contested. The fact that Kieseritzky did not arrive at Folkestone until 24 May now seems to detract somewhat from the argument for 25 May, as he would have needed to travel from Folkestone to London, settle into his hotel, meet Anderssen, etc., and there would have been less time to do these things if he had played the Immortal Game on 25 May (a Sunday). Conversely, the case for 26 May may be considered enhanced.

Another “Certificate of Arrival”, this time at the port of London, is dated 1 August 1851, and is signed “Lionel Kieseritzky” (National Archives, HO 2/223, certificate no. 5808).

No certificate of arrival in England prior to the 1851 tournament has so far been found for Anderssen.’

An item added to Cuttings on 24 November 2019:

On his chessgames.com page (a post dated 17 April 2019) Raymond Keene could not be bothered, following Tony Buzan’s death, to look up a Karpov v Buzan game which he himself had published in the Sunday Times (‘Maybe a search in ST archives wd locate it’).

The game-score was given by Raymond Keene in his Sunday Times column on page 53 of the Supplement, 15 December 1996. After asserting that the Immortal Game between Anderssen and Kieseritsky [sic] was played at Simpson’s in the Strand, for which there is no proof, the column stated (without any further information such as the precise date or occasion) that at Simpson’s in 1995 Anatoly Karpov (‘the World Chess Federation champion’) won the following game against Tony Buzan (‘a well-known author on the brain’): 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 b6 4 Nc3 Bb7 5 a3 h6 6 d5 Be7 7 e4 exd5 8 cxd5 d6 9 Bb5+ c6 10 dxc6 Bxc6 11 Bxc6+ Nxc6 12 O-O O-O 13 Bf4 Qd7 14 Rc1 Rfd8 15 Nd5 Nxe4 16 Rxc6 Resigns.

The Sunday Times column even asserted more specifically where, at Simpson’s, the Immortal Game was played: ‘in one of the upper rooms there’.

A brief extract from C.N. 11864, concerning Fifty Shades of Ray by Raymond Keene (Edinburgh, 2021):

Our feature article ‘The Immortal Game’ (Anderssen v Kieseritzky) shows how, over the years, Raymond Keene has rehashed various factual blunders about the 1851 brilliancy. Far from taking account of chess historians’ investigations, discoveries, corrections and conclusions, Fifty Shades of Ray remains incompetent over the most basic matters: yet again, for instance, the players are named as ‘Adolph’ Anderssen (also ‘Andersen’ on the same page, where we find too ‘the Ruy Lopex’) and ‘Kieseritsky’. The game, incidentally, features a ‘gradiose’ combination.

Additions on 30 May 2021:

As mentioned in C.N. 11364, nothing has been traced to show that the Anderssen v Kieseritzky brilliancy was labelled the ‘Immortal Game’ until some years after it was played. However, the following is on page 116 of Fifty Shades of Ray:

‘The vanquished player was so impressed with the brilliant execution of Anderssen’s attack that he immediately telegraphed the moves of the game to an awaiting audience at the Café de la Régence. From that day on [emphasis added here] this sparkling exploit has earned the soubriquet “The Immortal Game”.’

C.N.s 11357 and 11364 concluded that the available evidence strongly indicates that the Immortal Game was played at the St George’s Chess Club, Cavendish Square, London, whereas no contemporary source has been found to suggest that the venue was Simpson’s. Nonetheless, Raymond Keene continues to state categorically and sourcelessly that the game was played at Simpson’s, and there is even this on page 111 of Fifty Shades of Ray:

‘This was a game so brilliant that top-hatted runners dashed down the Strand from Simpson’s, where the game had been played, to telegraph the moves to the Cafe de la Regence in Paris, the epicentre of chess life in the French capital.’

That article (number 23 in the book) had been posted on-line on 24 May 2020. The following week (see page 119 of Fifty Shades of Ray) Raymond Keene reiterated:

‘... the “Immortal Game” of London 1851, one of the most brilliant chess victories of all time, was played on Simpson’s hallowed turf.’

He wrote similarly at the same website on 5 December 2020:

‘Simpson’s was the location of this week’s masterpiece, known as The Immortal Game, won by Anderssen in 1851. So impressed were both the loser and the onlookers that top-hatted runners were despatched down the Strand to telegraph the moves to the Café de la Régence in Paris ...’

Again, no source was provided. Regarding that second reference to ‘top-hatted runners’, we note the same phrase in an historical article about Simpson’s but in a different context, and with no reference to the Immortal Game, telegraphing or the Café de la Régence:

‘Chess plays a prominent part of Simpson’s history, and chess matches were played against other coffee houses in the town, with top-hatted runners carrying the news of each move between the various houses.’

A further extract from the above-mentioned 5 December 2020 article by Raymond Keene, concerning Simpson’s:

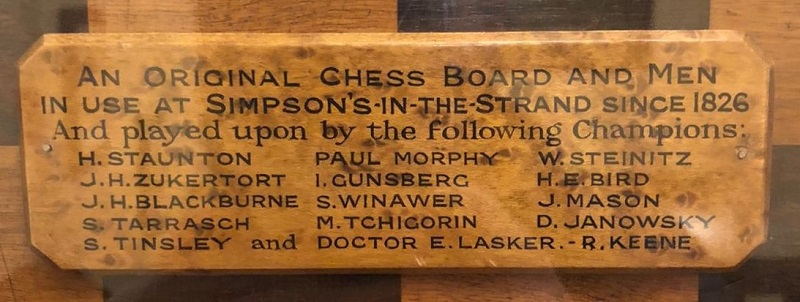

‘A famous chess board and pieces situated at the top of the main staircase still commemorates the exploits on the 64 squares of such chessboard immortals as Howard Staunton, Adolph [sic] Anderssen, Paul Morphy and Emanuel Lasker. On my 50th birthday the genius loci Brian Clivaz ... invited me to play a couple of games on this hallowed chessboard turf, and generously inscribed my name on the plaque, along with the gods of the game.’

The plaque does not mention Anderssen.

C.N. 11004 referred to the defilement of the plaque, and two photographs are reproduced here with permission but without further comment:

Mention of Arkady Dvorkovich in C.N. 11003 prompts Olimpiu G. Urcan to point out these Twitter exchanges involving Nigel Short and Raymond Keene:

Raymond Keene’s inability to recognize Arkady Dvorkovich is as pitiful as his pride in the defilement of the Simpson’s-in-the-Strand chessboard (as shown on a Kingpin webpage).

(11004)

It will be appreciated if readers can trace other appearances of the game in nineteenth-century primary sources, and not least publications in German and French.

(11871)

Blackburne briefly annotated the Immortal Game in an article in The Strand Magazine, December 1906, pages 722-725. See Zukertort v Blackburne, London, 1883.

Robert Hübner analysed the game on pages 14-35 of issue 3 of the American Chess Journal (1995). The article ended with a list of 27 ‘major works cited’.

See too The Best Chess Games. For other games by Kieseritzky, see Chess Jottings.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.