Edward Winter

The present article considers two neglected figures of the past, Govind Dinanath Madgavkar and T.A. Krishnamachariar (or Krishnamachari).

***

From page 16 of A Century of British Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1934):

‘I went up [to Trinity College, Oxford] in Michaelmas Term, 1890, and at once joined the University Chess Club, where the chief exponents of the game were G.D. Madgavkar, the brilliant Indian player, with his astonishing sight of the board, which enabled him to leave his own game and wander round, looking at others and passing acute comments on their prospects; and R.G. Lynam …’

On page 299 Sergeant wrote that Madgavkar was ‘now Sir Govind Dinanath Madgaonkar, Judge of the High Court in Bombay, and Acting Chief Justice when he retired in 1931’.

Finding games by Madgavkar is not easy, but here is one, played while he was at Oxford (Balliol College) and taken from pages 266-267 of the May 1892 Chess Monthly:

Govind Dinanath Madgavkar – Henry Ernest Atkins

Oxford University v Cambridge University match, 7 April 1892

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 d6 4 d4 Bd7 5 Nc3 Nf6 6 Bg5 Be7 7 Bxc6 Bxc6 8 d5 Bd7 9 Qd3 Nxd5 10 Nxd5 Bxg5 11 Nxg5 c6 12 Ne3 Qxg5 13 Qxd6 O-O-O 14 Qa3 Kb8 15 O-O-O Be6 16 f3 Bxa2 17 Rd2 Rxd2 18 Kxd2 Rd8+ 19 Ke2 Bc4+ 20 Ke1 Ba6 21 Qc3 Rd6 22 Kf2 g6 23 g3 h5 24 Ra1 h4 25 Ra5 hxg3+ 26 hxg3 Bb5

27 Rxa7 Ba6 28 Rxa6 bxa6 29 Qb4+ Kc7 30 Nc4 Rd4 31 Qb6+ Kc8 32 Qxc6+ Kd8 33 Qa8+ Ke7 34 Qxa6 Qc1 35 Qa3+ Kf6 36 Qc3 Kg7 37 f4 Rd1 38 Qxe5+ Kh7 39 Ne3 Rd2+ 40 Kf3 Qh1+

41 White resigns. (‘For if 41 Kg4 then 41…f5+ and 42…Qh5 mate’ – the Chess Monthly.)

Hoffer proffered this same explanation of White’s resignation in his Field column, but, as the July 1892 Deutsche Schachzeitung (pages 207-209) pointed out, there is no mate for Black after 42 Kg5. The German magazine gave 41 Kg4 Rd6 42 Ng2 (if 42 f5 then 42…Qh5+ 43 Kf4 g5 mate and if 42 Qg5 then 42…f6, etc.) 42…Re6. However, since 42…f6 allows 43 Qh4+ the correct line for Black would be 42 Qg5 Qxe4.

The BCM (May 1892, page 196) also considered White’s resignation to be premature, and it described Madgavkar as ‘a very original and ingenious player’.

So who was he? We are grateful to Balliol Library for providing biographical details from the Balliol College Register:

‘Born 21 May 1871, eldest son of D.V. Madgavkar, Maharastra Gand Saraswah Brahmin. Educated at St Xavier’s School, Bombay; Elphinstone College, Bombay (B.A.). At Balliol from Hilary Term 1891 to 1892. [Comment by the Library: as he already had a degree from Elphinstone, he must have done a short course at Balliol for the Indian Civil Service.]

Indian Civil Service 1892: Sessions Judge 1905; Judge, Sind Chief Court 1920; Judge of the High Court, Bombay 1925-31; Kt. 1931; retired from the Indian Civil Service 1931; Adviser to Holkar State 1933; Nyaya Sabha, Baroda State, 1938; President, Bombay Revenue Tribunal 1939-44, and Judge of Supreme Court, Kolhapur State.

Married Saraswati Bhadrabai, daughter of R.B. Shankar Pandurang Pandit, Bombay: two sons, one daughter.

Died April 1947.’

(3193)

Few nowadays may recognize the name of T.A. Krishnamachariar (1899-1956), but in his time he was highly praised for his chess writing and problem compositions, as well as for making a unique contribution to the development of chess in India. For example, in a feature on pages 31-33 of the January 1940 BCM T.R. Dawson wrote:

‘The Madras paper, the Hindu, has easily the largest chess “column” in the British Empire, for until the war caused some reduction in size it was often four, five or six columns long. But there was far more than mere size to give it importance, for T.A. Krishnamachariar has edited it with a brilliance and a knowledge very rare in newspaper chess. Without any shadow of doubt, he has succeeded in building around his fine work a flourishing school of young Indian composers whose work gains in strength every year.’

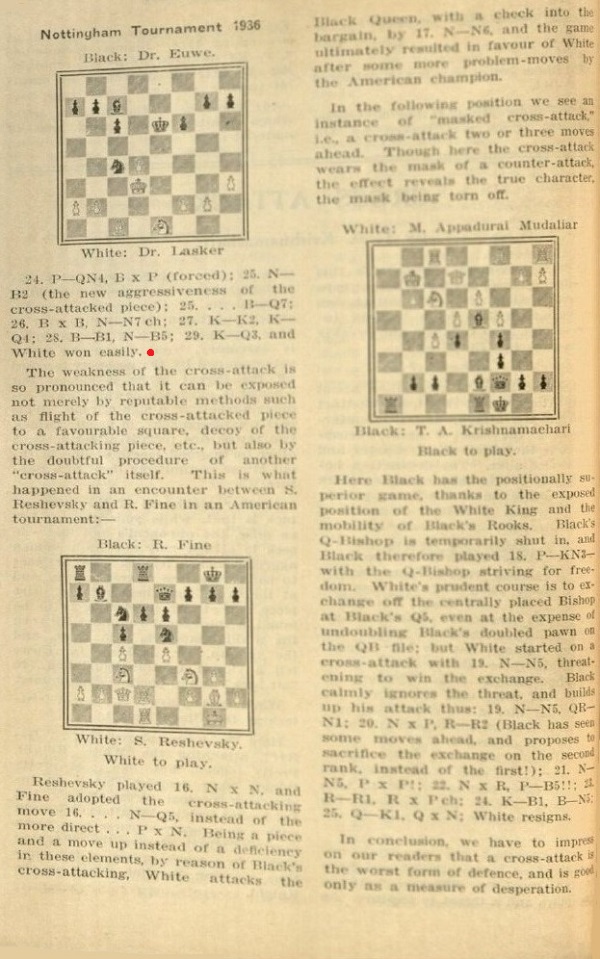

Dawson gave 12 of Krishnamachariar’s problems, including the following two-mover from the Indian Chess Magazine, 1931:

Under the heading ‘Memorial to a Great Indian’, M.R. Parameswaran wrote from Madras on page 73 of CHESS, 30 November 1956:

‘The late Mr T.A. Krishnamachariar, as you are no doubt aware, was for a quarter of a century the only link between chess life in India and the rest of the world. By his devoted service he made the Hindu chess column world-famous. But his greatest contribution to chess was the unification of chess life in India and the popularization of the international rules of the game, which are now almost universally accepted in India. This last task was more difficult than one might realize; more difficult than introducing chess to a non-chessplaying population. For in India chess has been played, for centuries, all over the country, but, alas, with the rules varying from district to district. To persuade these players to turn their backs on their traditional sets of rules and adopt the “European” rules has not been easy, and it is no small achievement to have succeeded in that task during a period when India was under alien rule, in economic poverty and political ferment with extreme nationalistic feelings running high.’

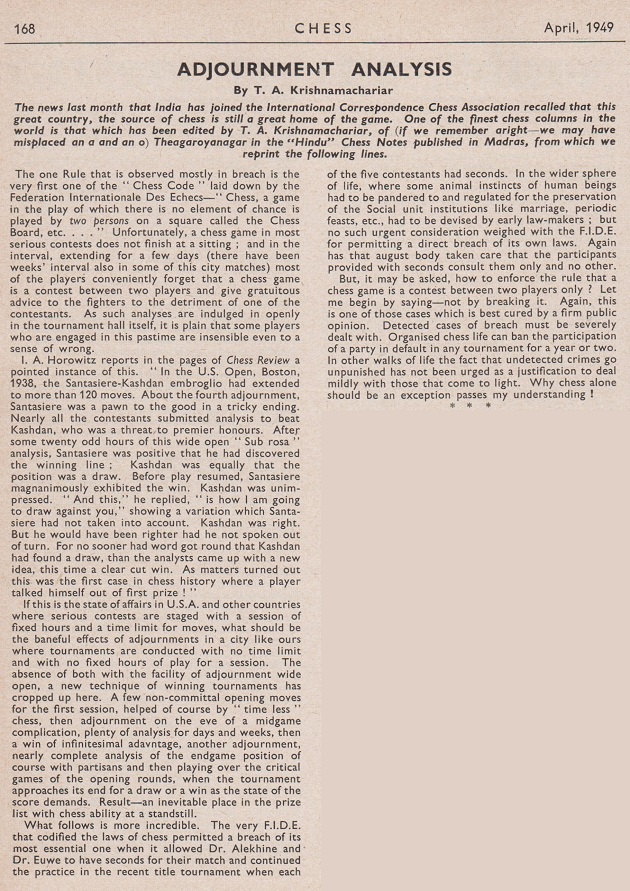

One of the few specimens of Krishnamachariar’s writing that we have seen is an article entitled ‘Adjournment Analysis’ which CHESS, April 1949 (page 168) reproduced from the Hindu, describing his output as ‘one of the finest chess columns in the world’.

(3391)

Noting that Emanuel Lasker was 67 when he defeated Euwe at Nottingham, 1936, José Carlos Santos (Porto, Portugal) asks whether any even older player has ever beaten a reigning world champion under standard tournament or match conditions.

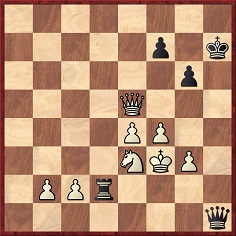

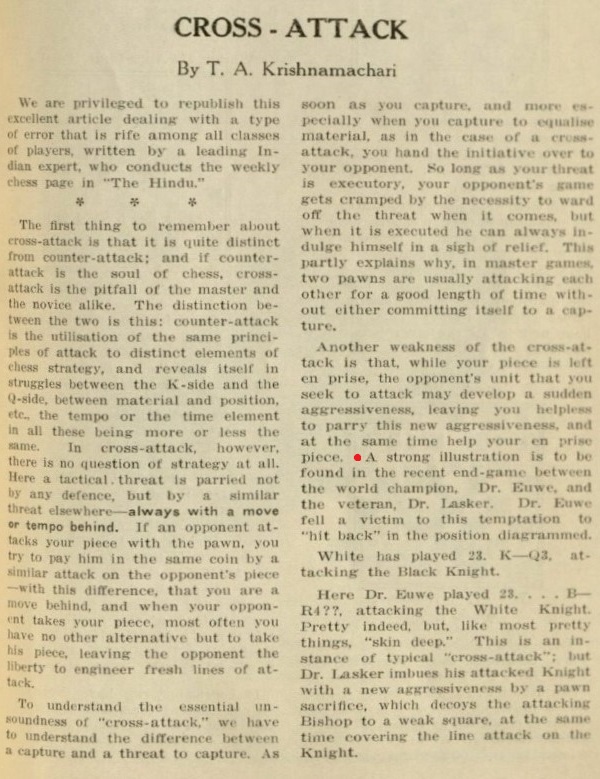

We add that Lasker’s famous win was discussed on pages 23-24 of the January 1937 Australasian Chess Review in an article by T.A. Krishnamachari. Its title, ‘Cross-Attack’, is a seldom-seen technical term.

This photograph of T.A. Krishnamachariar (also Krishnamachari) is taken from an article about him by T.R. Dawson on pages 31-32 of the January 1940 BCM. See too the entry on pages 214-215 of Indian Chess History 570 AD-2010 AD by Manuel Aaron and Vijay D. Pandit (Chennai, 2014)

(11020)

Impressed by the article entitled ‘Cross-Attack’ shown in C.N. 11020, Sean Robinson (Tacoma, WA, USA) asks to see more of the Indian author’s output in the Hindu. C.N. 3391 above referred to the difficulty of tracing his columns and mentioned one, ‘Adjournment Analysis’, reproduced on page 168 of CHESS, April 1949:

From page 33 of The World Chess Championship: 1951 Botvinnik v Bronstein by William Winter and R.G. Wade (London, 1951):

(11031)

Page 8 of the Linlithgowshire Gazette, 1 January 1932 published a win by the Indian:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 h6 4 Bc4 Bc5 5 d4 Bb6 6 O-O a6 7 Bxf4 d6 8 Nc3 Nc6 9 Bxf7+ Kd7 10 Nd5 Nce7 11 Ne5+ dxe5 12 Qg4+ Kc6 13 Nb4+ Kb5 14 a4+ Ka5

15 Nc6+ Nxc6 16 Bd2+ Nb4 17 Bxb4+ Kxb4 18 c3+ Ka5 19 b4 mate.

The only information about the game is that it ‘was given lately in La Vie Rennaise, we think, played in India’.

(11034)

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) notes that although T.A. Krishnamachariar seems to have had no obituary in The Problemist, the following appeared on page 510 of the March 1954 issue:

(12012)

See too Sultan Khan.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.