Edward Winter

C.N. 671 showed that ‘insane’ was a favourite word in Essay on Chess by Anthony E. Santasiere (Dallas, 1972):

- ‘Now Capablanca! the great Capablanca (how well he knew it!), the perfect machine, the fiery temperment [sic] with, especially in his prime, the cold, selfish heart, the incredible insane conceit – Capablanca.’ (page 23).

- Page 24 (Capablanca again): ‘But as he grew older there was a sad downtrend (unlike, for instance, Lasker of [sic] Mieses). The weakening was more spiritual in nature than physical, though I believe that in his prime he was insane – i.e., incapable of recognizing an equal competitor ...’

- Rossolimo ‘had been temporarily insane’ (page 43).

A letter from T.W. Sweby in the March 1984 CHESS (page 268) mentions in passing that it took two years of correspondence on both sides of the Atlantic to explode the Cambridge University loss of a game to Bedlam Insane Asylum story.

(748)

See The Cambridge v Bedlam Chess Story.

Harry Nelson Pillsbury

From page 267 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, April 1905:

‘Mr Pillsbury was operated on at the Presbyterian Hospital, Philadelphia on 27 March, and a few days later, while in a high fever, he tried to jump from a fourth story window. He was finally controlled and returned to bed.’

Or, as A. Bisguier and A. Soltis recounted the story on page 76 of American Chess Masters from Morphy to Fischer (New York, 1974):

‘… he tried to commit suicide by jumping from the fourth floor of a Philadelphia hospital where he was being treated for mental disorders.’

Sidney Bernstein has provided information about the murder committed by Raymond Weinstein:

‘I have it on most reliable authority (the author John Collins, who was a close friend of Raymond Weinstein) that Weinstein (an extremely strong and promising young player who finished third in the 1960-61 US Championship) had been confined to a mental institution. While on temporary leave, he was rooming with an older man who made derogatory remarks about Weinstein’s mother. Raymond slit the man’s throat with a razor, and was, of course, incarcerated permanently. Raymond’s mother is also in an asylum.

Incidentally, Raymond once invited me to lunch at his home (before the above troubles, of course). His father, who was also present, struck me as a terrible person who tyrannized and terrorized the family. He was a good chessplayer, but talked incessantly about the golf trophies he had won. In retrospect, it was easy to understand why Raymond and his mother were committed.’

(1311)

See also Chess and Murder.

What opening was named after an institution for the insane?

(1732)

See The Danvers Opening (1 e4 e5 2 Qh5).

The March 1989 Revista Internacional de Ajedrez (pages 12-15) has an interview with the Spanish-born master Francisco José Pérez, a Cuban resident since the early 1960s. His reminiscences on Alekhine are of interest, and his replies to F.J. Ochoa de Echagüen included the following:

‘I will mention that in general he spoke well of the majority of chessplayers, except Nimzowitsch, who he said was mad. ...

(1854)

From the article ‘The mating game’ by Bernard Levin on pages 171-174 of his anthology All Things Considered (London, 1988):

‘It is dangerous; too many great players have been on the edge of madness, or over it, for it to be a coincidence. The mind of a grandmaster is something that cannot be properly understood, so extraordinary is its ability; and those of the handful of what may be called the supergrandmasters defy imagination.

... I sometimes think that the real wonder of supergrandmasters is that a good many of them are perfectly sane.’

The article first appeared on page 16 of The Times, 9 November 1987.

From page 79 of the 2002 edition of Chess Lists by A. Soltis:

‘The most tragic case belongs to Paulino Frydman, a little-known Polish master who was invited to the Bad Podĕbrady, Czechoslovakia international of July 1936. Surrounded by several world-class players – including Alexander Alekhine, Salo Flohr, Erich Eliskases and Gideon Stahlberg – he astounded them by allowing only a draw in his first seven games. But two rounds later, with a score of 8-1, he lost to Alekhine and suffered a nervous breakdown. Frydman scored only one and a half points in his last eight games and finished as an also-ran. He was never again a significant figure in chess.’

There were similar words from Sourceless Soltis on page 81 of the 1984 edition of his book. In reality, though, from the field of 18 masters Frydman finished equal sixth with Eliskases, and his significant over-the-board achievements in subsequent years are a matter of public record. As regards the ‘nervous breakdown’ part of the story, it may be wondered if Soltis had any solid information of his own or was merely copying from Wolfgang Heidenfeld’s entry on the Podĕbrady tournament in The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977).

Next, a typical Internet item by Bill Wall:

‘Frydman, Paulino (1905-1982)

A leading Polish player during the 1930s who represented his country in seven Olympiads. He used to run around nude in hotels yelling, “fire”.’

Wall writes similarly at another website:

‘Paulino Frydman was a leading Polish player during the 1930s who represented his country in seven olympiads. He used to run around nude in hotels yelling “fire”.’

Or again:

‘The Polish master Frydman also ran around nude, but usually in hotels while yelling, “fire”.’

At yet another Internet site, Wall disseminates a slightly dressed-up version of his story:

‘The Polish master Paulino Frydman represented his country in seven chess olympiads. He liked to clear out hotels by running down the halls in his underwear yelling, “Fire!”’

At no stage, of course, has Wall given any further particulars, but a similar tale may be recalled from The Psychology of the Chess Player by Reuben Fine. On page 65 he wrote:

‘During a chess tournament in Poland a Polish master by the name of A. Frydman was reported to have gone berserk and to have run through the hotel without any clothes on shouting “Fire!”’

This may seem strange. We have been repeatedly assured by Wall that the master in question was Paulino Frydman, so why did Fine write ‘A. Frydman’? Moreover, Fine suggests that the incident in question occurred once only, whereas Wall is ostensibly privy to information that it was Frydman’s frequent conduct (i.e. what he ‘used to’ do, ‘liked to’ do and ‘usually’ did). Finally, given that Podĕbrady was in Czechoslovakia and not Poland, where Fine places the tournament in question, how might any of this tie in with Soltis’ reportage?

We note that page 44 of CHESS, 14 October 1937 contained the following piece under the heading ‘What really happened?’:

‘Variations of the following weird theme have appeared in a number of British and American newspapers. We reproduce without comment:

“In a chess tournament at Jurata, Poland, a contestant, Willy Frydmann, lost a game then went raving mad.”’

So now we have ‘Frydmann’ instead of ‘Frydman’ and ‘Willy’ rather than either ‘Paulino’ or ‘A’.

Pages 197-198 of the July 1937 Deutsche Schachzeitung had a brief account of the Jurata tournament, a 22-man contest in May/June for the Polish championship. It was won by Tartakower ahead of Ståhlberg and Najdorf, and the Deutsche Schachzeitung stated that P. Frydman finished last but two, with 6½ points, having withdrawn after losing in the 15th round and suffering a nervous breakdown. (‘Frydman erlitt, als er in der 15. Runde verlor, einen Nervenzusammenbruch und musste aus dem Turnier ausscheiden.’)

However, the full crosstable of Jurata, 1937 was given on page 374 of the December 1937 Wiener Schachzeitung, and it stated, correctly, that the player who finished 20th was A. Frydman. Earlier (page 152 of the May 1937 issue) the Wiener Schachzeitung had named the player as Achill Frydman and had referred to ‘den tragischen Unfall Achill Frydmans, der mit einer schweren Nervenerkrankung in eine Heilanstalt überführt werden musste’.

Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia lists ‘Achilles Frydman (1905-circa 1940)’, a player with an entry on page 276 of Szachy od A do Z by W. Litmanowicz and J. Giżycki (Warsaw, 1986). Perhaps a Polish correspondent can locate further details. And perhaps – a true long shot, this – one or two writers will consider it appropriate to substantiate their assertions about Paulino Frydman. For our part, we have found no contemporary report mentioning fire, nudity or underwear.

(2917)

From Tomasz Lissowski (Warsaw):

‘It is true that Achilles Frydman of Łódź (and not the more famous Paulin(o) Frydman of Warsaw, and later of Buenos Aires) had serious health problems in the late 1930s. Two quotations follow, the first being from the column in Polska Zbrojna by Colonel M. Steifer at the time of the Jurata, 1937 tournament:

“Najdorf could have easily won first prize, had it not been for an irritating incident with A. Frydman, who caused many difficulties for the tournament management and for the players. This cost Najdorf two points: the games he lost against Gerstenfeld and Schächter in winning positions.”

Further information is given by Tadeusz Wolsza on page 32 of the third volume of his dictionary of Polish chess players, Arcymistrzowie, mistrzowie, amatorzy (Warsaw, 1999):

“Near the end of the tournament Achilles Frydman fell ill. After one of his numerous lost games he was the victim of a strong attack of fury, and doctors placed him in a mental asylum in Kocborowo. This unfortunate case ended his chess career. He never returned to competitive chess, and his occasional off-hand games were only against friends.”’

(2932)

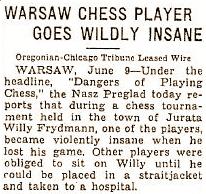

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) refers us to page 10 of the eighth issue of the Spanish magazine Ocho x Ocho Especial (January 1995), in which Román Torán quoted Albéric O’Kelly de Galway as stating that at Łódź, 1938 ‘Friedman’, entirely naked, turned up 15 minutes late for his game against Tartakower. It is not specified where the Belgian master wrote the item attributed to him by Torán.

(3290)

Now we add the handling of the affair by Koltanowski, from an article entitled ‘People are the craziest!?’ on page 186 of Chess Digest Magazine, August 1971:

‘[L]et me start at the beginning of this true story:

We quote from the Jurata (Poland) morning paper of 11 August 1937:

“In the International Chess tournament of Jurata, 21 of the 22 competitors have suddenly become stark crazy. They have decided to continue with the tournament and finish their 21 games in 14 days. Only one participant was sensible enough to retire to a resthome.” End quote.

The player in question was Anton Frydman, a Pole who a few days before the start of the tournament, had just been released from a Mental Institute and had been warned by the doctors not to play chess for a good while. Yet Frydman persuaded the tournament organizers to allow him to play in the tournament. In the first rounds he played good chess. He managed to draw with Xavier Tartakower, who eventually won the tournament. But the way the chess masters played, NO adjournments, playing two games a day, almost each day, with a total of 12 to 14 hours of mental work daily, sometimes even longer, something had to give.

In the 12th round Frydman started his shenennigans [sic]! During his game with Miguel Najdorf, Frydman ran to the phone after every move, placing long-distance calls collect, ordering such important articles as a bicycle from Germany, a flute from Hungary, etc. The next day he had to be locked up in his room ... he insisted in walking around in the lobby in his Adam’s suit. Gideon Stahlberg, who had the misfortune of having the room next to Frydman, couldn’t sleep at night. His (opponent) next-door neighbor was calling out check and check-mate all night long in a very loud voice.

That was when the committee decided to have Frydman returned to his Resthome ... and the players met to vote if they should continue the tourney under those terrible long hour conditions. They finished the event!’

The ellipses in the above passage are Koltanowski’s.

What he terms ‘this true story’ is just a further example of the Koltanowski drivel-machine at full throttle. He did not participate in the tournament, and the origin of many of his claims is unknown to us. A number of them, however, are contradicted by the details in Four Polish Championships by T. Lissowski (Nottingham, 2003), which gives all available games from Jurata, 1937 and some background information (noting, for instance, that the tournament took place from 23 May to 6 June 1937 and that ‘three games were to be played every two days’). The following points, in particular, may be listed:

a) Although the tournament finished on 6 June, Koltanowski claims to be quoting a topical-sounding newspaper item which he dates over two months later: 11 August 1937. (It may seem ungracious to criticize Koltanowski on a matter where, for once, he attempted to cite a documentary source, but he failed even to name ‘the Jurata (Poland) morning paper of 11 August 1937’ from which he was purportedly quoting.)

b) Koltanowski refers to ‘Anton’ Frydman. His forename was Achilles.

c) Another incorrect statement by Koltanowski is that Frydman drew with Tartakower. In fact, Tartakower won (in round 2).

d) Koltanowski is also wrong to indicate that Frydman’s game against Najdorf was in the 12th round. They met in round 15.

e) Nothing has been found to support Koltanowski’s assertions about Frydman’s withdrawal from the tournament.

(3567)

C.N. 2917 (see above) quoted from page 44 of CHESS, 14 October 1937 the following piece under the heading ‘What really happened?’:

‘Variations of the following weird theme have appeared in a number of British and American newspapers. We reproduce without comment:

“In a chess tournament at Jurata, Poland, a contestant, Willy Frydmann, lost a game then went raving mad.”’

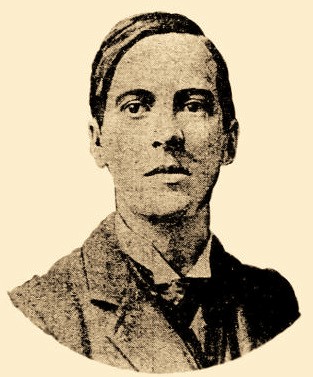

Russell Miller (Vancouver, WA, USA) has found one of those newspaper reports, on page 3 of The Oregonian, 10 June 1937:

Can a reader find what had appeared in the Polish publication mentioned (whose correct title is Nasz Przegląd)?

(7084)

Below is how half of page 66 of Objectif mat! by Raoul Bertolo and Louis Risacher (Paris, 1978) was filled:

(9370)

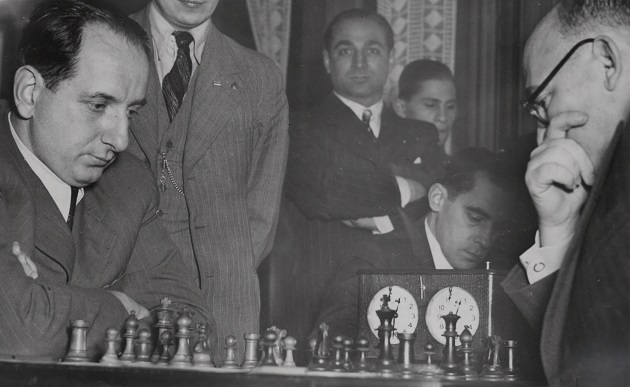

courtesy of the Crítica archive, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) sends this photograph:

It will be recalled that Paulin(o) Frydman (White) has been the victim of negligence by chess writers so eager to have fun with insanity that they muddled him with a lesser-known, similarly-named player.

(12183)

See also Reuben Fine, Chess and Psychology.

See too Chess and Psychology.

From an interview with Capablanca in New York World, 25 October 1925:

‘Chess was greatly injured in the United States when two of its foremost players, many years ago, were credited with having been driven insane because of their absorption in the game. There was not a word of truth as to either of these men, yet the propaganda became so widespread and your newspapers made so much of it that the man or woman who took up chess came to be regarded as a little ‘strange’.

I often have had men and women of otherwise fine intelligence actually ask me if I did not fear I would lose my reason by continuing to play the game. It seems a fixed idea among many Americans that facility or expertness in the game indicates some mental disorder.’

(3000)

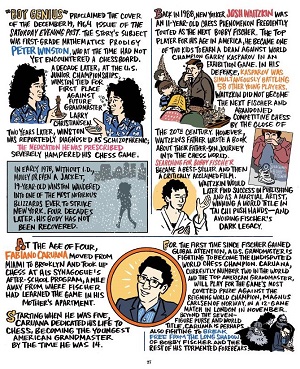

Morten Hansen (Frederiksberg, Denmark) has pointed out to us the following paragraph about Morphy on page 105 of G. Ståhlberg’s book Strövtåg i schackvärlden (Skara, 1965):

‘The first signs of mental illness, which was probably the result of syphilis contracted in Paris, could be observed in the following years. During the Civil War he lived in Havana and Paris. He later returned to New Orleans. His mental illness grew worse, but when his family once tried to have him committed to an institution he gave such sensible and lucid answers to all the questions that he was not accepted as a patient.’

Ståhlberg’s grounds, if any, for the suggestion about syphilis are unknown to us, but some documentary evidence does exist to corroborate his other remarks. Pages 293-294 of Paul Morphy The Pride and Sorrow of Chess by David Lawson quoted from Charles Maurian’s letter about Morphy in the Watertown, New York Re-Union of December 1875:

‘Outside of the persecution question, he remains what his friends and acquaintances have always known him to be, the same highly educated and pleasing conversationalist.

An attempt was made to induce him to remain in the “Louisiana Retreat”, an institution for the treatment of insane persons, but he objected and expounded to all concerned the law that governed his case and drew certain conclusions with such irrefutable logic that his mother thought, and in my opinion very properly, that his case did not demand such extreme measures as depriving him of his liberty, and took him home.’

(3384)

See also Paul Morphy, ‘Fun’ and The Pride and Sorrow of Chess.

A story which Irving Chernev was fond of telling:

‘In 1850 an old passion for chess awoke in Szechenyi (founder of the Magyar Academy) and took an insane character. It became necessary to pay a poor student to play with him for 10 or 12 hours at a time.

Szechenyi slowly regained his sanity, but the unfortunate student went mad.’

That appeared on page 40 of Chernev’s book Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974), and a similar version (‘The unfortunate student went mad, but Szechenyi slowly became sane’) was given by him on page 14 of Chessworld, January-February 1964 and on page 56 of Curious Chess Facts (New York, 1937).

In Curious Chess Facts he gave a source: ‘Lombroso in The Man of Genius’. Does any reader know what that book contained regarding Szechenyi and chess?

(4349)

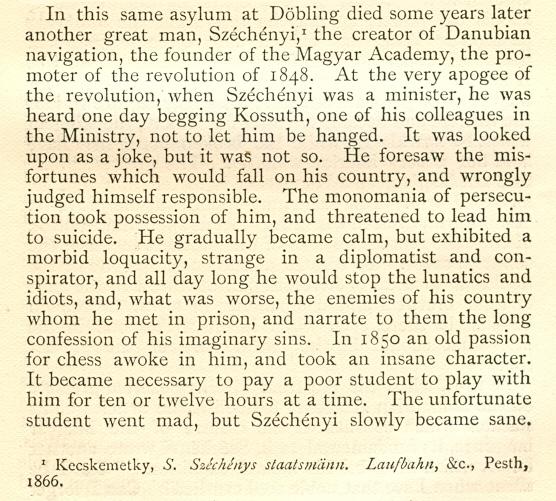

We can now reproduce what appeared on page 87 of Cesare Lombroso’s book (published in London in 1891):

As regards the footnote, the author of the 1866 volume, which we have not seen, should read (István) Kecskeméthy.

(5638)

We note webpages announcing the forthcoming publication by the Yellow Jersey Press of a book about Fischer, The Mad Master by Rene Chun. As if the title were not enough, the work is being touted as ‘the first biography’ of Fischer.

(4596)

The above item was posted in 2006. We have no further information about such a book.

The start of C.N. 5250:

From John Nunn (Chertsey, England):‘I recently received a pre-publication copy of White King and Red Queen by Daniel Johnson. In it I read (page 11) that “Rubinstein’s sanity, always precarious, gradually left him and he spent his last 30 years in a sanatorium”. A similar claim was made in another recent book, The Immortal Game by David Shenk, which stated (page 143) that “... [Rubinstein] spent the last 30 years of his life in a mental institution”. I was surprised both by these claims and the similarity between them (the precise 30-year figure).

I may be mistaken, but I had the impression that while Rubinstein may have suffered bouts of mental illness, he had regular contact with other players in the post-War years. Do you know of any evidence that might support the claims of Johnson and Shenk or is this just a myth?’

We took up Dr Nunn’s query in Akiba Rubinstein’s Later Years.

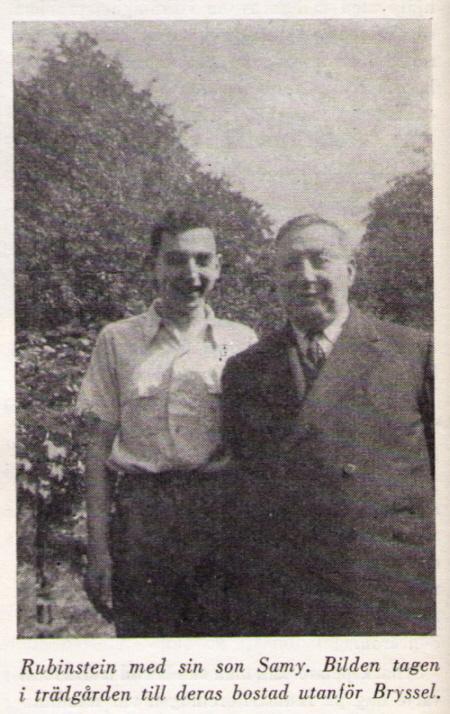

This sketch of A. Rubinstein by his son Sammy is reproduced courtesy of John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA). It appears on page 380 of the 2011 monograph which he co-wrote with N. Minev (C.N. 7572).

Mr Donaldson comments to us that the latest photograph of Rubinstein known to him was published on page 124 of the June 1949 issue of Tidskrift för Schack. We are grateful to Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) for the scan below:

(7584)

‘Lasker and Schlechter signed a secret protocol’ is the heading on page 46 of The Genius and the Misery of Chess by Zhivko Kaikamjozov (Newton Highlands, 2008), and the following page affirms:

‘The match rules [i.e. for the 1910 encounter] weren’t published anywhere and the above-mentioned clauses were secret, known only by the players and two confidants. The protocol from the match was revealed much later, after the death of the last of the four men who knew the secret.’

Naturally the ‘two confidants’ are left unidentified, as is the person who revealed the ‘protocol’, as well as everything else that the reader would expect to be told.

Another heading, on page 26, reads: ‘Mister Morphy, you have won the match, because you are stronger than me.’ These words, according to Mr Kaikamjozov, ‘Staunton pronounced in broken French’. Overleaf it is averred that, later on, Morphy ‘became paranoid, despised everyone’ and that ‘a loaded gun was kept on his bedside table at all times’.

That Morphy chapter (pages 23-29) shows the author at his most fabulistic, and we have seldom seen anything quite so bad.

(5855)

From Raymond Kuzanek (Hickory Hills, IL, USA):

‘On page 29 of his book The Genius and the Misery of Chess (Newton Highlands, 2008) Zhivko Kaikamjozov states:

“In 1867, Morphy embarked for Paris for treatment. The most prominent French psychiatric specialists tried hard to help him, but without any success. The only lasting effect was the emptying of his pockets, which soon led to his return to America.”

Unfortunately, Mr Kaikamjozov does not specify his sources of information. Do you recall any prior mention, with substantiation, of Morphy receiving psychiatric care in Paris?’

We do not.

(8468)

Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) quotes from Steinitz’s ‘Personal and General’ column on pages 369-370 of the International Chess Magazine, December 1887:

‘No doubt, the great mental exertion which proficiency in the game imposes on its foremost practitioners taxes brain and nerve to an extent which makes chess masters liable to more or less troublesome disorders during a heavy contest. But usually this sort of sickness, or chess fever, does not last long, and it ought to be made a rule that a great chess practitioner has no more right to be ill than an athlete or a soldier on the battlefield; and if he is, it should only be taken as a sign of weakness and unfitness for chess mastery. The world is sick enough of maladies, and knows very well that it is more easy to become ill than to preserve, or eventually to recover, that serene balance of mind which is essentially necessary for the exercise of healthy mental action. On that subject, and on the relations between body and mind, I think “the art of human reason”, as chess has been termed, is destined to throw some light, just like bodily gymnastics have greatly contributed toward the knowledge of our structure and of the conditions under which physical strength can be acquired and maintained.’

Our correspondent also notes the early use of the term ‘chess fever’.

(6065)

From page 287 of Bobby Fischer Uncensored by David and Alessandra DeLucia (Darien, 2009) we reproduce a note by Fischer dated 8 July 1999:

‘The Jews claim that I’m mentally ill but they’re the ones who are mentally ill. What terrible hatred inside of them compelled them to forge an illegal mating variation in the Batsford edition of “My 60 Memorable Games” in my game with Bolbochan. And in the 1988 Faber and Faber edition of “My 60 Memorable Games” what compelled them to forge “winning the Bishops pawn” rather than what I really wrote “winning the two Bishops”. They’re the ones who are mentally ill!!!’

(6214)

From R.J. Buckley’s chess column on page 21 of the Birmingham Weekly Mercury, 1 July 1905:

‘Chess does not make for insanity. The study of chess makes for sanity – makes the sane more sane than before. Nations of chessplayers are the sanest, must be the sanest, of nations. The Irish lunatic asylums are thicker on the ground than in any other country. The Irish are not chessplayers. They become lunatics because they lack the brain exercise that chess, or something like chess, could give. Chessplayers are the sanest people in the world, just as athletes are the strongest. Athletes are strong and healthy through using their muscles. Chessists are sane because they keep their brains in working order.’

(6494)

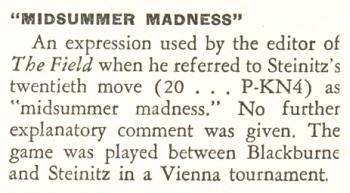

From the Dictionary of Modern Chess by Byrne J. Horton (New York, 1959):

C.N. 530 (see page 144 of Chess Explorations) commented briefly on ‘midsummer madness’. We add here that the exact wording in The Field, as quoted on page 333 of the October 1873 Chess Player’s Chronicle, of the note to 20...g5 in Blackburne v Steinitz, Vienna, 1873 was:

‘If this is not midsummer madness, it is something very like it.’

(6861)

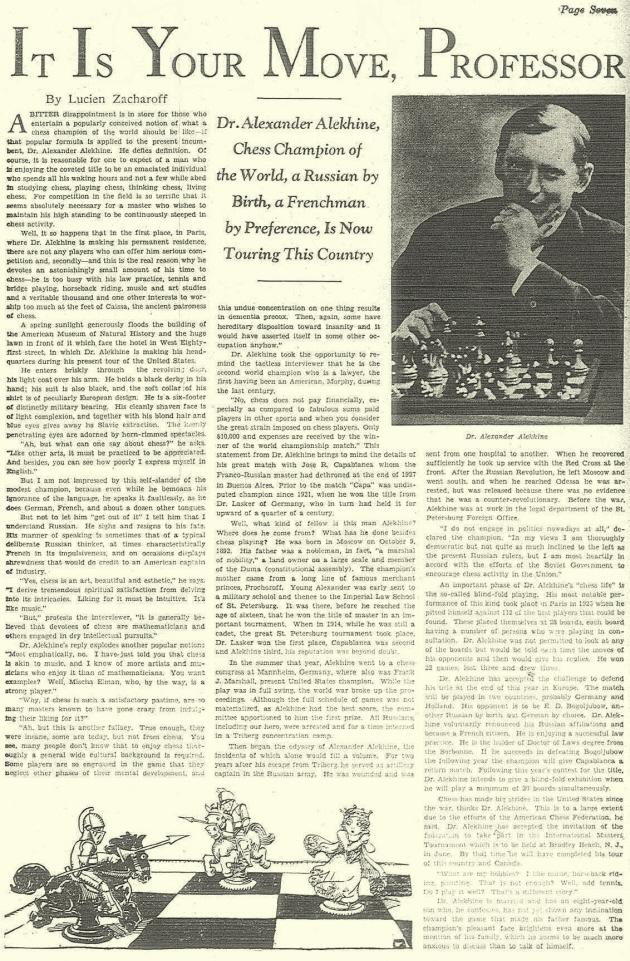

An interview with Alekhine, by Lucien Zacharoff, was printed on page 7 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 19 May 1929. A copy has been received from John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA):

Asked why so many masters are ‘known to have gone crazy’ from indulgence in chess, Alekhine replied:

‘Ah, but this is another fallacy. True enough, they were insane, some are today, but not from chess. You see, many people don’t know that to enjoy chess thoroughly a general wide cultural background is required. Some players are so engrossed in the game that they neglect other phases of their mental development, and this undue concentration on one thing results in dementia precox. Then, again, some have hereditary disposition toward insanity and it would have asserted itself in some other occupation anyhow.’

(7260)

Sean Tobin (Phoenix, AZ, USA) asks:

‘Have any serious professional studies been published on the historical incidence of insanity in top-level chess? Does insanity strike more players, on average, than other groups of people?’

(7303)

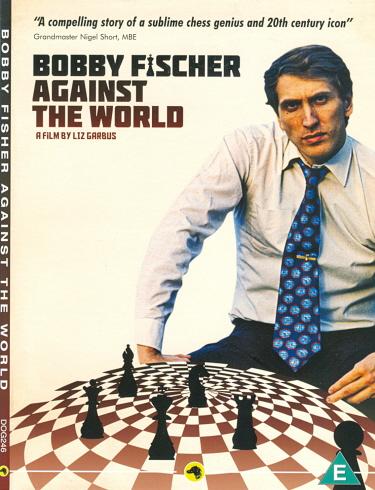

Graced with some exceptionally rich archive material, Liz Garbus’s 2011 documentary film Bobby Fischer Against the World is disgraced with some exceptionally poor interviewees. A particular low point, with some of the talking heads less concerned about being truthful than noticed, is the dense sequence which seizes on the issue of insanity:

Anthony Saidy: ‘Victor Korchnoi claimed to have played a match with a dead man and he even provided the moves.’

Asa Hoffmann: ‘Rubinstein jumped out of the window because the fly was after him.’

Anthony Saidy: ‘Steinitz in late life thought he was playing chess by wireless with God Almighty – and had the better of God Almighty.’

Asa Hoffmann: ‘Carlos Torre took all his clothes off on a bus.’

To highlight only the Steinitz versus God yarn, no scrap of serious substantiation is available. Once again we witness the magnetic pull of malignant anecdotitis. And since the theme is insanity, an uncomfortable question arises: can such groundless public denigration of Steinitz and others be considered the conduct of a rational human being?

(7345)

Richard Reich (Fitchburg, WI, USA) has supplied the article ‘Mental States in Famous Chess Players’ by Louis Miller, published on pages 414-418 of the Illinois Medical Journal, October 1914.

(7710)

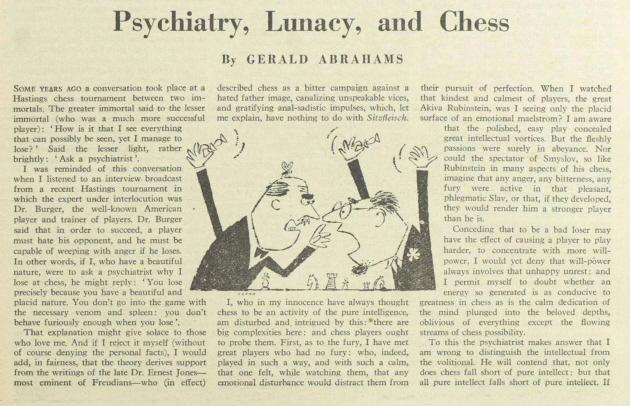

Olimpiu G. Urcan forwards an article by Gerald Abrahams from pages 743-744 of The Listener, 27 October 1960:

The text is markedly different from the article of the same title reproduced on pages 26-36 of Abrahams’ book Not Only Chess (London, 1974).

(8139)

Extracts from ‘Reflections after Reykjavik’ by Gerald Abrahams on pages 84-90 of Encounter, March 1973 were given in C.N. 10497. In addition, page 89 of the article had stories about Rubinstein (who ‘was under the impression that a fly was crawling across his scalp’), Torre (who ‘decided to take his clothes off in the streets of Buenos Aires’), Steinitz (who ‘used to claim to be mad – long before his chess powers diminished’) and Morphy (who ‘retired to nursing home in Boston where he spent the rest of his life’).

C.N. 711 reported that after we complained to a columnist, James Pratt (Odiham, England), that he had published assertions about Torre taking his clothes off in a bus, Weaver W. Adams being addicted to bicarbonate of soda and Steinitz claiming that he could offer pawn odds to God, we received this reply, in a letter dated 8 February 1984:

‘You are probably correct that my anecdotes about Steinitz, Torre and Adams are untrue but I was writing purely to amuse myself. I would be very stupid if I spent hours and hours on an article, weeks on research before that, only to have it dismissed as 25% of my stuff is.’

See too pages 266-267 of Chess Explorations, which furthermore noted:

‘It makes a good story’ was also the reply received from Fred Wilson after we complained that he had published inaccuracies regarding Staunton’s background.

Another specimen is ‘you must admit it makes a good story’, a remark made to us by Larry Evans. Our feature article on him includes the following:

From the back cover of Evans’ book This Crazy World of Chess (New York, 2007):

In Chess Thoughts we offer this general suggestion:

Praise received should be quoted sparingly, and never when from a disreputable source.

See also our feature article on Carlos Torre.

A Psychobiography of Bobby Fischer by Joseph G. Ponterotto (Springfield, 2012) shows little discernment between good chess sources and bad ones, although neither type can be blamed for the particular carelessness in the appendices on pages 163-171. For example, it is stated that the second Fischer v Spassky match was in 2002, and that the birth-year of Fischer’s mother and of Paul Morphy was 1949.

(7151)

C.N. 9252 referred to Bobby Fischer’s ‘apparent insanity’. See, in particular, Brad Darrach and The Dark Side of Bobby Fischer.

A very free French-language adaptation of Stefan Zweig’s story in comic-strip form has been produced by Thomas Humeau under the title Le joueur d’échecs (Paris, 2015):

(9730)

On the other side of the title page there is only this:

The customary English version of the remark attributed to Korchnoi is ‘No chess grandmaster is normal; they only differ in the extent of their madness’. That wording can be found, for instance, on page 13 of Essential Chess Quotations by John C. Knudsen (Osthofen, 1998), a booklet with no sources. How far back can the observation be traced, in any language?

(9731)

‘Chess is not something that drives people mad; chess is something that keeps mad people sane.’

That observation by William Hartston is readily found in chess literature and on the Internet, usually without a source. At best, there may be a reference to Bobby Fischer Goes to War by David Edmonds and John Eidinow (London, 2004). From page 69:

The book’s bibliography lists four works by William Hartston, but in none of them do we see the remark. Mr Hartston informs us that he does not currently recall its exact provenance.

A paragraph on page 104 of The Psychology of Chess by W.R. Hartston and P.C. Wason (London, 1983):

There is, furthermore, this description of chess on page 11 of The Kings of Chess by William Hartston (London, 1985):

‘A game to subdue the turbulent spirit, or to worry a tranquil mind.’

As mentioned on page 377 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, that observation was included in The Penguin Dictionary of Twentieth Century Quotations by J.M. and M.J. Cohen (London, 1993 and 1995):

(10823)

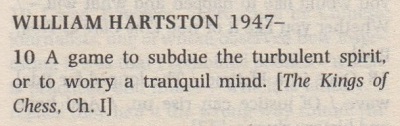

Olimpiu G. Urcan draws attention to a cartoon feature on pages 26-27 of the November-December 2018 Playboy: ‘American Chess Masters’ written by Brin-Jonathan Butler and illustrated by Nathan Gelgud.

The left-hand section on Morphy refers to ‘a spooky child prodigy’ who later ‘traveled across Europe and toured royal courts ...’ Then comes this ‘Fun’:

The treatment of Steinitz does not even attain the ‘according to legend’ and ‘reports abound that’ level:

(11086)

See too page 109 of The Psychology of Chess by Fernand Gobet (Abingdon, 2019).

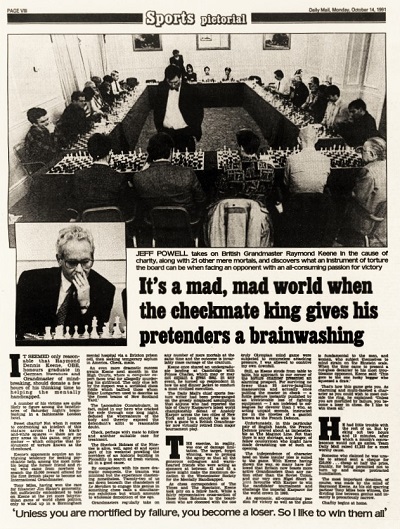

Our feature article on Tony Miles refers to an article (‘It’s a mad, mad world when the checkmate king gives his pretenders a brainwashing’) by Jeff Powell, on page VIII of the Daily Mail, 14 October 1991:

An extract from the early part:

‘Keene’s opponents acquire an intriguing tendency for seeking psychiatric help, among the most notable being the former friend and rival who came from nowhere to snatch the £5,000 reward offered for the first British player to become an International Grandmaster.

Tony Miles, having won the race for financier Jim Slater’s generosity, felt sufficiently emboldened to take on Keene at the yet more labyrinthian game of world chess politics, only to wind up in a Birmingham mental hospital via a Brixton prison cell, then seeking temporary asylum in America. Check, mate.

An even more dramatic success awaits Keene next month in the High Courts, where a computer expert faces trial for allegedly murdering his girlfriend. The only clue left by the suspect was a scribbled chess riddle which baffled those whom Edgar Lustgarten used to describe as “the finest brains of New Scotland Yard”.

The Lancashire Constabulary, in fact, called in our hero who cracked the code through one long night, deduced the whereabouts of the body and thereby exposed the defendant’s alibi to reasonable doubt.

Check, perhaps with mate to follow and another suitable case for treatment.’

In a letter to us dated 20 January 1992 G.H. Diggle commented on the article:

‘I have seldom read such dreadful stuff.’

See also ‘Ex Acton ad Astra’ on pages 18-33 of the Spring 2007 issue of Kingpin.

A Times tweet posted by Raymond Keene on 16 January 2013:

Addition on 29 January 2025:

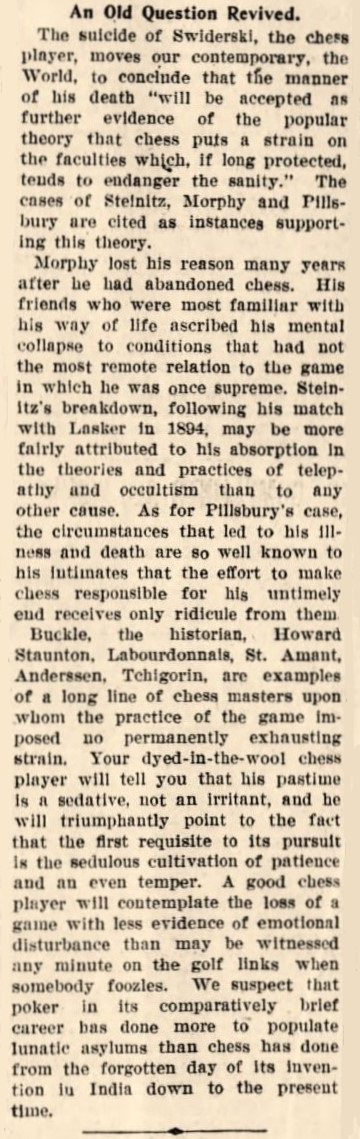

From page 4 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 13 August 1909:

See The Riddle of Swiderski’s Suicide.

Addition on 21 April 2025:

As mentioned in Chess and the Wallace Murder Case, in a statement dated 25 January 1931 Detective Superintendent Hubert Moore asserted (for unclear reasons) regarding Wallace:

‘The motive is obscure, but a solution is probably to be found in his affliction – he has only one kidney and that is failing – which is often associated with various forms of insanity.’

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.