Edward Winter

In a series of items we shall be examining a period often skated over by historians, i.e. the re-emergence of organized chess after the Second World War and up to the 1948 world championship match-tournament.

In early 1946 the President of the United States Chess Federation, Elbert A. Wagner, Jr., announced the imminent re-organization of FIDE and a resumption of activities broken off in Buenos Aires in 1939. Various magazines carried reports to that effect, examples being the January-February 1946 American Chess Bulletin (page 4) and the March 1946 BCM (page 85). A driving-force in disseminating the news was Hermann Helms, who was then the USCF’s Publicity Director.

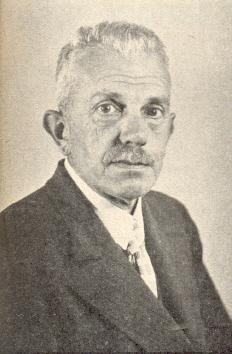

Alexander Rueb

Alexander Rueb, who had been the President of FIDE since its foundation in 1924, announced that a general meeting of the Federation’s delegates would be held during the summer of 1946. The above-mentioned BCM item (a statement by Helms) said that this meeting would be held…

‘… in Zurich, to which city the FIDE headquarters were transferred from The Hague before the German occupation of The Netherlands. The Swiss Chess Federation will be the host. In the meantime officials of 44 national organizations affiliated with the FIDE will have an opportunity of studying the plan of procedure mapped out by President Rueb.

Of prime importance will be the resumption of the biennial team matches for the trophy donated by the late Hon. F.G. Hamilton-Russell, of England [who had died in 1941]. This trophy, it is understood, is still in Buenos Aires, where, with the United States (four times winner of it) unrepresented, it was won by the German team.

It is proposed to divide the national units of FIDE into five areas or zones … Referring to the Soviet Union, the prospectus sent to all the units says:

“Europe is awaiting and expecting the affiliation of USSR chessplayers. By the collaboration of this great area, where chess is developing as perhaps nowhere else, the consolidation of European chess would be accomplished. The Government and chess authorities of the USSR are urgently requested to take once more into consideration the eventuality of joining the new FIDE.”

Switzerland is proposed as the seat of the International Federation. D. Hajek, of Zurich, a member of the Permanent Fund Commission, has been in charge of that fund since 1940. A Central Committee, consisting of three officers and five executive members from various units, will be in active control, and a divisional committee will have directive authority. The laws of the game and regulations for tournament and match play, including matches for the world championship, will come up for consideration at the Congress this summer.’

At that time the most commonly evoked solution concerning the world title was an Alekhine-Botvinnik match, but Alekhine died in late March 1946.

Alexander Alekhine

The FIDE Congress took place not in Zurich but in Winterthur, on 25-27 July, and we follow here the detailed report by the Swiss delegate, Erwin Voellmy, on pages 169-171 of the November 1946 Schweizerische Schachzeitung.

Voellmy related that since its 1938 Congress in Paris FIDE had shown no sign of life. The President, located in occupied Holland, had been unable to administer anything and the member federations (with the exception of Denmark) had no longer been paying their annual subscriptions. FIDE had practically ceased to exist.

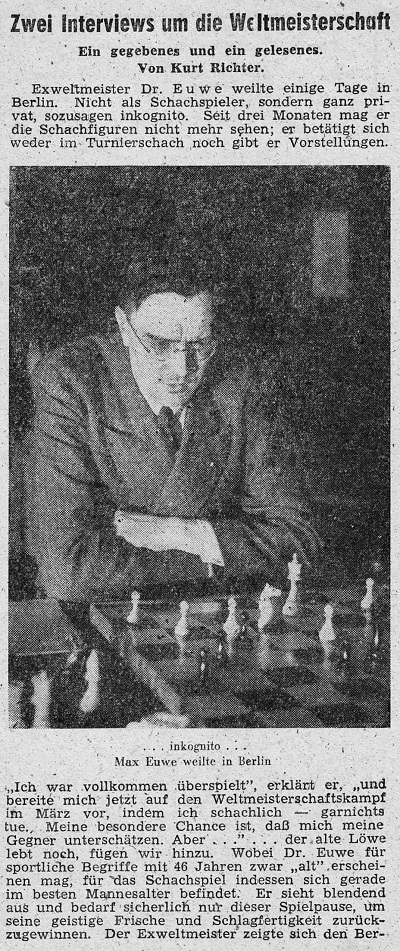

FIDE Congress, 1946. Left to

right: K. Opočenský, H. Meyer, J. Louma, Count G. dal

Verme, B.H. Wood, A. Rueb, M. Berman, E. Voellmy, M. Euwe, F.

Peeters

Difficulties regarding travel and finance made it impossible for many countries to be present at the Winterthur Congress, the full list of participants being:

Three working sessions took place (in addition to various sub-Committee meetings), and in view of the limited level of participation the decisions would be valid only until the 1947 Congress. A telegram was received from Moscow apologizing for the absence of Soviet representatives and requesting that the USSR be represented in future FIDE Committees. This was regarded by the Congress as a positive sign that the Soviet Union intended to join the Federation. Also on the membership front, Czechoslovakia, the Netherlands and France had ordered their delegates to oppose the admission of Spain, and a decision to that effect was taken. Countries such as Germany, Austria and Poland were not on the membership list in view of the absence of a recognized national federation.

As regards the world championship, it was decided in Winterthur to fill the vacancy by organizing, exceptionally, a tournament among the top candidates, i.e. Euwe, Botvinnik, Keres, Smyslov, Fine, Reshevsky and one of the winners of the upcoming Groningen and Prague tournaments. To settle the qualification issue regarding the future candidates a commission was appointed, comprising Rueb (Chairman), Louma (Vice-Chairman), Sir George Thomas, O. Bernstein and E. Voellmy.

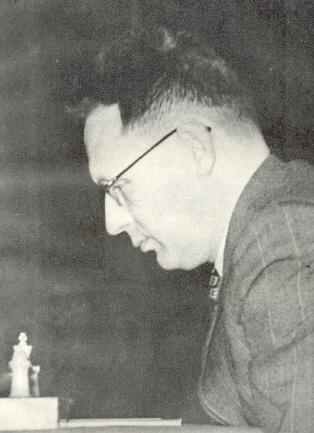

Erwin Voellmy

An inconclusive discussion was held on a rehabilitation request by Bogoljubow, which even introduced the name of Hans Frank (who, three months later, was hanged at Nuremberg). To quote from Voellmy’s account:

‘La demande du maître Bogoljubow, membre actif du parti nazi pendant une période de la guerre, de se faire réhabiliter par une cour d’honneur, maladroitement documentée entre autres par une lettre du Gouverneur Frank (alors à Nuremberg), fut renvoyée, faute de témoins, à un autre comité, dont M. M. Berman et Prof. Hugo Meyer font partie. On constata du reste que si le maître Bogoljubow n’est pas nommé parmi les candidats éventuels au Championnat du monde, c’est uniquement par son manque de succès (1er prix) dans les tournois depuis longtemps.’

And so the first steps had been taken to bring FIDE back to life and create some semblance of administrative order. However, our next instalment will relate how the Federation’s world championship plans suffered a crisis well before 1946 was over.

The FIDE Secretariat in Lausanne has sent us the minutes (French version) of the Congress in Winterthur in July 1946, and the document provides a number of details which complement the Voellmy report discussed above. For example, it was decided that the world championship tournament (four rounds) would take place in the Netherlands in June 1947, offers having also been received from the United States and Argentina. As previously noted, Euwe was chosen as a participant (by dint of having held the world title), and the federations of the United States and the USSR were given until 1 September 1946 to nominate other masters from their respective countries if they were not satisfied with FIDE’s selection of Reshevsky, Fine, Botvinnik, Keres and Smyslov. The minutes also stated:

‘If the winners of the tournaments in Groningen and Prague are not among the six above-mentioned masters, they shall play a match in Prague organized by the Czechoslovak Federation under the auspices of FIDE. The winner of that match shall be added to the list of participants. If one of the winners of those two tournaments is already on the list of participants, the other shall automatically qualify. Should the envisaged match end in a draw, the Qualification Committee shall decide upon the procedure.’

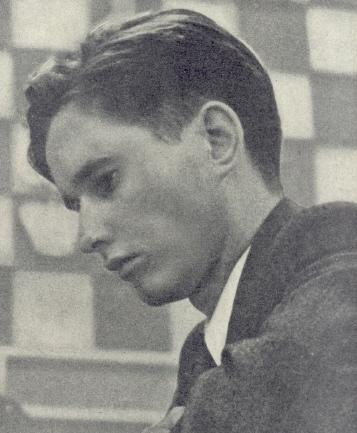

Vassily Smyslov

The minutes then set out FIDE’s seven-year plan for the future of the world championship. It is summarized below:

1947: World championship tournament, the Netherlands.

1946/47: Zonal championships (to be completed by 1 January 1948), open to the countries’ national champions.

1948: Interzonal tournament, with 20 participants. The players would be the qualifiers from the previous phase and masters admitted by the Qualification Committee.

1949: Candidates’ tournament (two rounds), comprising ten players. The participants would be the five players who had scored best in the 1947 world championship tournament and the five players with the highest scores in the above-mentioned Interzonal tournament.

1950: Match for the world championship between the winner of the title in 1947 and the winner of the Candidates’ tournament.

1949/50: New cycle of zonal tournaments.

1951: Interzonal tournament.

1952: Candidates’ tournament. (This would comprise the five top players from the 1949 tournament, as well as the 1947 champion if he lost his title in 1950.)

1953: Match for the world championship.

Prize money was specified only in the case of the 1950 world championship match: $6,000 for the winner and $4,000 for the loser.

With this complementary information on record, it is our third instalment that will relate how FIDE’s plan soon began to founder. Later on, we shall be discussing the 1947 Congress, which took place in The Hague. If any reader can send us a copy of the minutes thereof (at least regarding the issues under discussion here), we shall be most grateful, as FIDE is unable to supply them.

Samuel Reshevsky

Even before the July 1946 FIDE Congress in Winterthur all kinds of plans had been ventilated in chess magazines, one of the most detailed being by Eugène Znosko-Borovsky, on pages 170-172 of the June 1946 BCM. Written shortly after Alekhine’s death, his article disapproved of the idea, already current, of deciding the world championship by a tournament, since that would ‘carry a certain element of luck and hazard’. Znosko-Borovsky also introduced some complications regarding the selection of candidates:

‘No doubt Fine and Reshevsky are considered the strongest players in the United States. But the actual champion is Denker; he could not, therefore, legitimately be left out. In the meantime, he has been challenged by Steiner, and thus we have four prospective candidates from the USA alone.’

He believed that a de jure and de facto examination of the situation led to a number of conclusions, the first being:

‘Among living masters Euwe alone has been champion of the world. He lost his title to Alekhine. With the death of Alekhine the title reverts to Euwe as a matter of course.’

Max Euwe

Yet Znosko-Borovsky recognized that ‘the chess world might not willingly accept this solution’, notably because Euwe’s victory ‘is now ten years old’. He continued:

‘Alekhine’s first challenger since the War, therefore the last challenger to the title, is Botvinnik. Alekhine accepted the challenge. The title goes to him by default if death can be called default and not a matter of force majeure. In any case Botvinnik has more right than anyone to contest the title and, being the first player in the USSR and with Alekhine out of the lists, he must undoubtedly be considered the strongest player today.

Thus a match between these two great masters, one having the formal right and the other the required qualifications, would be the fairest solution.’

The BCM commented that Znosko-Borovsky’s suggestion of an Euwe v Botvinnik match ‘deserves earnest consideration’, but by early summer 1946 the momentum was running in favour of a tournament. Znosko-Borovsky had, though, been right to anticipate difficulties over the selection of players in such an event. The October 1946 CHESS (page 1) reported:

‘Mr Rueb informs that the Soviet authorities have not submitted alternative nominations for the world championship, so that Botvinnik, Keres and Smyslov become the USSR contenders. The USA have protested that the coincidence of the Prague tournament with the USA championship rules out the possibility of a further US master qualifying by winning the Prague tournament. This protest will hardly receive world sympathy in view that, to the two nations playing this match, five out of the six places in the final world championship tournament have already been allotted.’

Further details of the US position were given on page 1 of the November 1946 Chess Review:

‘When the International Chess Federation invited two American players to participate in the world championship it took for granted that Sammy Reshevsky and Reuben Fine were to be the American representatives. There is a widespread feeling among outstanding American chessmasters that the decision should have been left to the United States Chess Federation; that Reshevsky and Fine, pre-eminent as they are, should establish their right to play in the world championship tournament on the basis of present, rather than past, achievements.

What the players have proposed, and their position is backed by the United States Chess Federation, is that this country’s representatives be selected from the forthcoming United States Championship: the players who finish first and second are to be nominated by the Federation to play in the world championship tournament.’

On 2 October the USCF informed FIDE of its decision by cable. Chess Review thought it ‘very likely that the USCF plan will succeed’, whilst also noting, ‘An additional complicating factor is Reuben Fine’s inability to find time for playing in the US championship’. That tournament, held in New York in October-November 1946, was won by Reshevsky, 2½ points ahead of Kashdan. Around the same time the Prague tournament introduced a new name into the calculations, since it was won by M. Najdorf by a margin of 1½ points.

And still the ideas kept coming. Page 132 of the November-December 1946 American Chess Bulletin gave a suggestion from H. Meek, the Secretary of the British Chess Federation: ‘a triangular contest among Mikhail Botvinnik of Russia, Dr Max Euwe of The Netherlands and Samuel Reshevsky, recently winner, for the fifth time, of the United States Championship’. The options were endless, and FIDE’s frustration became manifest after it emerged that the USSR was also expressing dissatisfaction with the Winterthur solution. Under the title ‘World championship bust-up’, page 63 of the December 1946 CHESS gave this account:

‘Holland having got together £4,000 for the world championship tournament planned by the FIDE next June, Euwe arranged a meeting of the six prospective participants (himself, Fine and Reshevsky of the USA and Botvinnik, Keres and Smyslov of the USSR) at Moscow. At this, Botvinnik in anger stated that one Dutch paper during the Groningen tournament [won by Botvinnik, ahead of Euwe and Smyslov] had said that the Russian participants might work together to put him into first place. He therefore refused to play for the championship in Holland. Russians know no ‘freedom of the press’. It was finally agreed to stage the event half in Holland, half in Russia, but there was further argument over the question of where the first half should be held.

The USSR has not joined the International Chess Federation (FIDE). At the last FIDE Assembly Spain, who had been a founder-member and had paid its dues throughout, was ejected in the hope that the Soviets would join; the sacrifice has deeply wounded Spanish sentiment.

The Russians want the tournament in April, Fine not before August. Estimates of the cost of Holland’s half of the tournament are now rising to £6,000 and £7,000.

Dr Rueb, President of the FIDE, has withdrawn FIDE’s claim to organize the tournament, which work lies mainly between Euwe (for the Dutch Federation) and the Russian Chess Federation at the moment.’

Mikhail Botvinnik

Summarizing the situation in its final issue of the year (December 1946, page 5) Chess Review declared, under the heading ‘Snail’s Pace’:

In short, all the positing, posturing and postulating throughout 1946 had resulted in virtually nothing, and the chess world entered its tenth consecutive year without a world championship contest.

The imbroglio facing the chess world at the turn of the year (1946/47) was well summed up by J.F.S. Rumble in a letter published on page 15 of the January 1947 BCM. He identified ‘two time-honoured principles’ which, he said, had been over-ridden by FIDE’s intended arrangements: ‘a player’s nationality has nothing whatever to do with his skill at chess’ and ‘the title of world champion is won by match play’. Noting that the various ‘delegations’ were fighting for the right to select their own representatives, he wondered: ‘Has the aftermath of this last world war left us so drugged that even the world chess championship must become a matter of international bickering?’

Another letter published by the BCM (April 1947 issue, pages 122-123) was from Norman T. Whitaker (‘Retired, undefeated, Champion National Chess Federation, USA’). Writing from Shady Side, MD on 24 January 1947 he declared:

‘When we analyse the fundamentals, however, the problem solves itself … for it is simple. May I, an old-timer, give my observations? I assert Dr Euwe is the chess champion of the world. Alekhine won it from him in 1937. On the death of Alekhine, last 24 March, the title automatically reverted to Euwe.’

The most significant contribution to the discussion during the first half of 1947 (i.e. in the run-up to FIDE’s General Assembly) was a lengthy general article on the world championship by Botvinnik. At least two different English translations were published (on pages 168-169 of CHESS, March 1947 and pages 13-14 of the May 1947 Chess Review). Quotes below are from the former version.

After referring to past championship matches Botvinnik wrote:

‘Thus we see that there are two factors hindering a championship match between the holder of the title and his strongest rival: 1. the rival cannot always obtain the funds for such a match, and 2. the champion as a rule is not interested in playing a match with his strongest opponent.’

Attempting to identify the best way forward, he added:

‘It seems to me that a correct solution to the problem would be the existence of an authoritative World Chess Federation, having sufficient funds at its disposal accruing from contributions received from various countries. In this connection, it is necessary to state that the present federation – the FIDE – has neither the necessary funds nor the necessary authority: the last congress of the FIDE, held in Switzerland in July of the last year, was attended by representatives from only from six to eight countries, among whom were no representatives from either the USSR or the USA. If a truly authoritative organization existed, it would be fully able to arrange for the holding of both the elimination contests and the match for the world championship. Nevertheless, we must frankly admit that even if such a federation were organized, it is doubtful that the contributions received from various countries would be sufficient to cover expenses.

What is to be done at the present time, when no such organization exists? I would make the following suggestions:

1. Elimination contests (match-tournaments) for determining the candidate for the championship title should be obligatory. The expenses of these contests should be borne by the country in which they are held …

2. Within a given period, the world’s champion should be obliged to play with the winner of the elimination match-tournament. If the player who pretends to the title is able to obtain funds covering the expenses of the match in any particular country, the champion should go there to play unless the native land of the champion guarantees the expenses of the match. In the latter case, the match should be held in the native land of the champion, as was the case with the Alekhine-Euwe revenge match.

3. If the candidate to the championship is unable to find support for such a match in any country, and if the native land of the champion likewise refuses to support the match, then the world championship is to be considered open and the champion loses his title, i.e. the situation will be the same as that which exists at the present time. It is clear that then the new world champion will be determined by a match-tournament participated in by the leading candidates to the title.

Under such a system, not only the player who pretends to the title but the champion himself will be interested in having the match held, and it is to be expected that the two of them will quickly come to an agreement. The circumstances which formerly hindered the holding of title matches will now be eliminated.

Let us say a few words about the coming contest for the world championship. In September of last year, when the strongest chessplayers of the world were gathered here in Moscow (Keres, Reshevsky, Smyslov, Euwe, Fine and the author of this article) they held a conference (19 September) on the subject of the coming contest for the world championship. After the inevitable arguments, it seemed that a means of agreement was indicated. I do not wish to speak of this in detail, since I hope that by the time this article is published the situation will have become more clear. At any rate, I shall take upon myself the responsibility of saying that the Soviet grandmasters are for a match-tournament which will be participated in by all leading chessplayers, that they are for holding the tournament in the friendliest atmosphere possible, under conditions aiding each participant to reveal his greatest creative possibilities and enabling the strongest player to emerge the victor.’

In addition to the players listed by Botvinnik, there was still Najdorf to be considered. Indeed, immediately after the Botvinnik article CHESS printed a report on an interview in the January 1947 issue of El Ajedrez Español in which Najdorf had declared:

‘I believe that I am inferior to none of the players who are to participate in the next world championship, Botvinnik, Fine, Reshevsky, Keres, Euwe. …None of these have a better record than I. I have played much less than they have, admittedly, but I am satisfied with my results.’

M. Najdorf

As the players and national federations continued to jockey for position, FIDE prepared for what was expected to be its decisive congress, in The Netherlands in the summer of 1947.

Paul Keres

We conclude this series by turning now to the 1947 FIDE Congress, which was to finalize arrangements to determine Alekhine’s successor as world champion.

The Congress was held in The Hague from 30 July to 2 August 1947, and the Swiss delegate, E. Voellmy, gave an account in the October 1947 Schweizerische Schachzeitung (pages 154-155). He reported that the idea of an Euwe-Reshevsky match had been evoked and that a widespread wish existed in Eastern Europe for a Botvinnik-Keres match. Nonetheless, Voellmy recorded, the Russians had reverted to the Winterthur plan, and the agreement meant that March 1948 would see the start of a six-man tournament (Botvinnik, Keres, Smyslov, Euwe, Reshevsky and Fine), firstly in the Netherlands and then, following a two-week break, in Moscow. The event would go ahead even if any player withdrew, and Voellmy concluded with the observation that it would be a particularly arduous event for Euwe, Reshevsky and Fine, since the other three players were well acquainted with each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

B.H. Wood, another delegate in The Hague, stated in CHESS, September 1947, page 344, that ‘the final disagreement, over which country should have the honour of housing the more important concluding rounds, was decided by lot’. The same page gave the full text of the text ratified during the FIDE Congress in The Hague.

The United States’ representative was Paul G. Giers, whose official report to the USCF was related on page 107 of the September-October 1947 American Chess Bulletin. It was noted that the Dutch and Soviet Federations had agreed jointly to assume all the expenses, including travel and living costs, of the six masters, and the Bulletin added:

‘There were other propositions submitted to the meeting. One suggested a match between Dr Euwe, champion in 1935, and Reshevsky; the other, an enlargement of the plan and the admission of three or four additional masters regarded as eligible to compete for the honor. Both were voted down.

Because of the grounding of their plane at Berlin en route to The Hague, the four Soviet delegates, Ragozin, Postnikov, Yudovich and Malshev, did not arrive until the last day of the meeting, but, according to Vice-President Giers, cooperated in every way to make possible a harmonious understanding.

Of far-reaching effect is the entry of the USSR, hitherto outside of the Federation, into closer and permanent relationship with the other leading chess-playing nations as an affiliated unit. It is understood that Russia has 600,000 registered players.

The world organization, of which Dr A. Rueb of The Hague is the head, is now practically complete and its rulings will carry full weight. All major decisions are left to the General Assembly, which convenes annually and is attended by one delegate from each unit.’

Chess Review commented on page 2 of its August 1947 issue:

‘The FIDE has virtually revived its program of a year ago ... The line-up is exactly that given then, except for the provision including winners of the 1946 Groningen and Prague tournaments if not those already named. Botvinnik, already named, won at the former; but Mendel Najdorf won at Prague, would have qualified under the 1946 provisions. The only other alterations in the 1946 plans are the added delay to 1948 and the arrangement for half the play to take place in Russia.’

It was not until early the following year that Reuben Fine’s refusal to participate in the match-tournament was announced (although, by coincidence, the BCM had listed only Botvinnik, Euwe, Keres, Reshevsky and Smyslov in its brief mention of the Congress on page 300 of its September 1947 issue). From page 11 of the January-February 1948 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Bad news comes from the West in the announcement that Reuben Fine of Los Angeles has decided to withdraw from the tournament. The reason advanced for this unexpected step on the part of one of the heroes of the AVRO tournament was the necessity for his continuing a post-graduate course at the University of Southern California to avoid the loss of an entire year in the pursuit of his studies.’

Reuben Fine

Page 4 of the February 1948 Chess Review stated that the magazine had received a telegram from Fine: ‘Professional duties make it impossible for me to get away in time to play in the tournament.’ As noted in C.N. 2915 (see pages 262-263 of Chess Facts and Fables), Fine was later to offer various other reasons for his withdrawal (uncertainty as to whether the Russians would play and, if they did, under what conditions; the expense involved; a belief that the tournament as arranged was illegal). That earlier C.N. item also quoted a comment made by Fine in 1989:

‘TASS fabricated a story that I had had to desist because of career pressures. (In fact, I was not at that time employed; I was working on my doctorate.) The TASS story was a total fraud.’

As noted above, Fine’s telegram had used the term ‘professional duties’.

The March-April 1948 American Chess Bulletin (page 25) stated:

‘Last-minute efforts to include Reuben Fine of Los Angeles among the title seekers failed, in consequence of which the plans underwent a change. Instead of meeting each other four times, the players were required to add one game with each of his rivals to his schedule. Briefly, therefore, 12 games in Moscow, added to the eight at The Hague, make a total of 20 to be contested by each of those engaged in the title quest.’

Left to right: Max Euwe, Vassily Smyslov, Paul Keres, Mikhail Botvinnik, Samuel Reshevsky

Although page 80 of the March 1948 BCM observed, ‘There is no provision made for a substitute and thus the questionable side-tracking of Najdorf becomes little short of a calamity’, it would be an exaggeration to suggest that contemporary magazines (i.e. the sources on which this ‘Interregnum’ series has concentrated) accorded much thought to Najdorf’s fate. Fine’s absence too received few column inches, as attention was becoming firmly focussed on Botvinnik, Euwe, Keres, Reshevsky and Smyslov. Under FIDE’s firm control they joined battle for the undisputed world chess championship in The Hague, on schedule, on 1 March 1948, i.e. almost two years after Alekhine had died.

Mikhail Botvinnik and Alexander Rueb

The above feature article originally appeared as C.N.s 3006, 3018, 3028, 3048 and 3316.

The following passage by David Levy in a recent [25 May 2004] contribution to the ChessBase website is baffling:

‘In this whole debate there is one question that does not appear to have been considered in any depth – Who owns the title of World Chess Champion? I do not mean, who should currently be recognized as World Champion, but who actually owns the title? The way that the title came into FIDE’s possession is that it was “given” to FIDE by Botvinnik after he became World Champion in 1948. But was the title Botvinnik’s to give? No it wasn’t. He won it, he was the holder, but that is all. Botvinnik was never the owner of the title and therefore any “gift” by him of the title to FIDE could have no proper legal status. FIDE was certainly in possession of the title from 1948 until 1993, but not its owner.’

(3317)

From page 115 of CHESS, March 1946:

‘Botvinnik has written Mr Derbyshire, President of the British Chess Federation, saying that the Moscow Chess Club is willing to sponsor a world championship match Botvinnik v Alekhine and put up 10,000 dollars (£2,500). Two-thirds to go to the winner and the balance to be allocated to expenses. The BCF to organize the entire match. Mr Derbyshire is planning to commence the match during the tournament at Nottingham in August.’

From page 143 of CHESS, April 1946:

‘Alekhine has accepted Botvinnik’s challenge to a world championship match, subject to the conditions being the same as those under which he was negotiating to play Botvinnik in 1939. The British Chess Federation will be asked at its Executive meeting on 26 March whether it is willing to accept responsibility for organizing the event.’

From page 168 of CHESS, May 1946:

‘After considerable discussion, the BCF agreed to organize the Alekhine-Botvinnik match, but only because no effective International Chess Federation was in effective existence and only on condition that both players should bind themselves to submit to the ruling of such a Federation in connection with the next following match.

(Next day, Alekhine’s death was announced.)’

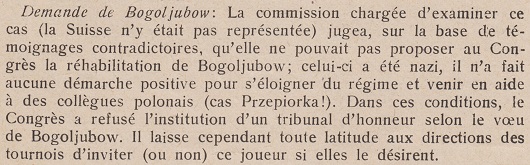

Further to C.N. 4821, below is Erwin Voellmy’s summary of the discussion at the FIDE Congress in The Hague (30 July-2 August 1947), from page 155 of the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, October 1947:

(9333)

During the interregnum, C.J.S. Purdy wrote an article entitled ‘The World Championship’ on page 100 of Chess World, 1 June 1946. After briefly referring to the London Rules and stating that with Alekhine’s death ‘the way is now clear for the FIDE to take complete control of the championship’, Purdy presented these proposals:

‘Match or Tournament?

Some advocate that the world title should be decided by tournaments.

After much thought, we disagree.

In the first place, a tournament proves nothing unless the winner’s margin is substantial; luck often plays a big part.

Further, the lifting of one tournament to overwhelming importance would reduce interest in other tournaments; before the War, big international tournaments were held frequently, and they aroused tremendous interest. Each big tournament was important in itself; it did not have to play second fiddle to anything. The proposed change would seriously jeopardize all that.

Nobody had any complaints against the match system except that matches were too infrequent and the champion more or less selected his challenger.

If matches are held at regular intervals of say 18 months or two years, and the challenger is selected by the FIDE on recent tournament results, there may still occasionally be faulty choices made, but there will undoubtedly be a vast improvement.

So the choice is between a revolutionary change which may be harmful, and an alteration which is certain to be beneficial.

Suitable conditions for a match would be: First to win four games, but by a margin of at least two points; provided that at least 12 games must be played, and not more than 24 games. After 24 games, the leader shall be champion. If scores equal, holder retains title.

In other words, do not let a one-point margin decide unless after a very protracted struggle neither player can do better. A 4-3 win after ten or 12 games would not be very satisfactory. On the other hand, if one player could build up a lead of four wins to two after 12 games it should be good enough. The strain of a 24-games match or longer should not be imposed unnecessarily. Labourdonnais and McDonnell killed themselves with long matches.

As to finance, we suggest a purse of 5,000 American dollars. Half the purse and expenses to be raised by the nation holding the match; the other half from a fund raised by the FIDE from subscriptions in all affiliated countries.

By all means hold a tournament to pick the first champion; after that, matches.’

On the subject of Bogoljubow and the 1948 world championship event, C.N. 2704 (see page 365 of A Chess Omnibus) sought, unsuccessfully, substantiation of this brief news report on page 215 of the July-September 1949 CHESS:

‘Bogoljubow has written in a Russian language newspaper circulating mainly in the States that he does not recognize the world championship tournament just concluded because he was not invited.’

Concerning Reuben Fine’s personal claims about the world championship, see C.N.s 5238, 6090, 6091, 10028, 10467 and 10470.

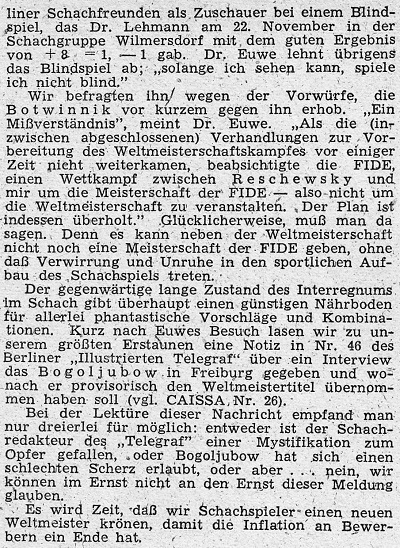

An exchange between Max Euwe and Kurt Richter which was quoted on page 35 of the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, March 1948:

Euwe: ‘When the championship negotiations reached an impasse, FIDE proposed organizing a match between Reshevsky and me for the championship of the Federation, but not for the world title. Once the impasse had been resolved, that spelled the end of FIDE’s plan.’

Richter: ‘Indeed, master, and that was no misfortune. A FIDE championship coming now on top of the world championship – what a source of confusion and rivalry that would have been in the chess world, the organization of which is already such a problem.’

(Kingpin 2001)

An article by Fritz Gygli and Jean-Charles de Watteville on pages 35-36 of the March 1948 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

Below, courtesy of Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada), is Kurt Richter’s earlier article, on pages 3-4 of Caissa, 2 January 1948:

(9100)

See also C.N. 11915, concerning a misrepresentation of our present article by a FIDE group advocating that Augusto De Muro should be regarded as the FIDE President from 1939/40 to 1946. See too C.N.s 11918 and 11925. Our feature article Chess: The History of FIDE has a section on the Rueb/De Muro affair.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.