Edward Winter

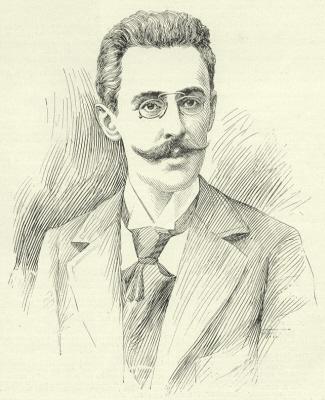

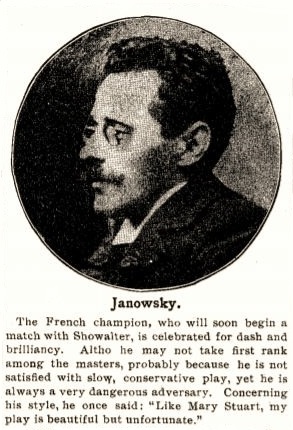

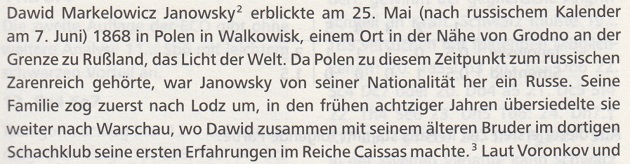

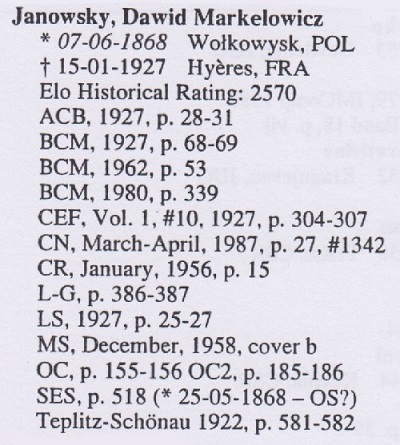

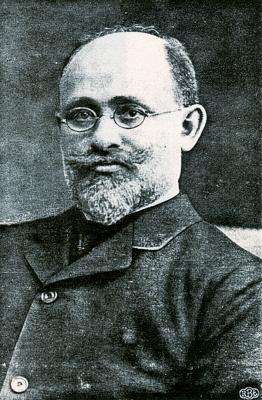

Dawid Janowsky (1868-1927)

‘Even at New York, 1924, the masters agreed that for the first four hours of play Janowsky was equal to any player in the world.’ So declared the obituary of Janowsky on pages 28-30 of the February 1927 American Chess Bulletin, which also stated that around the first few years of the century he ‘was the strongest player in the world’. Without going that far, Capablanca wrote in My Chess Career that Janowsky had been ‘one of the most feared of all the players’. In Diario de la Marina of 20 April 1913 the Cuban mentioned that Janowsky’s best period was ‘around 1902’.

Ossip Bernstein gave the following assessment on page 15 of the January 1956 Chess Review:

‘Janowsky was no chess scientist or theoretician. He knew what he had to do on the chessboard; but he did not know, or could not explain, why it had to be done. He had only two rules in chess: always attack; always get the two bishops (and, indeed, he used the advantage of the two bishops wonderfully). His main strength, indeed, was his extraordinary intuition, which gave him the exact feeling for what to do and how to do it.’

The didactic value of Janowsky’s handling of the bishop pair was also stressed by Alekhine. Writing in 1945, he noted that the prodigy Arturo Pomar had not yet learned the value of the two bishops and advised that ‘it would be very profitable for him to study the best games of Janowsky’. (Source: ¡Legado! by Alekhine, page 125.)

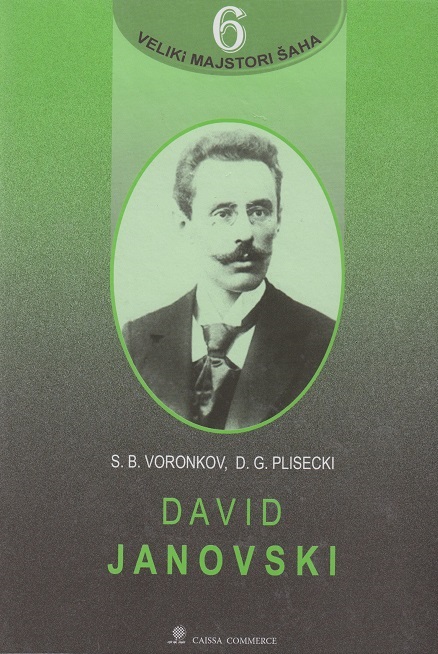

A prime characteristic of Janowsky’s playing style was its sheer energy, not to say restlessness. Little more than 20% of his tournament and match games were drawn. ‘Il n’est pas dans mon tempérament d’attendre’, he once declared (BCM, June 1909, page 261). His temperament has, in fact, attracted far more attention than his games or results yet he was, for instance, the only master apart from Tarrasch to beat the first four world champions, Steinitz, Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine. In all, he scored a dozen victories against them. Today, few brilliancies from his long career are kept alive, and only one book has been devoted to him, published in Russian in 1987. [See the updated information below.] His country of origin (Poland) has done noh more for his memory than have his adopted homelands (France and the United States).

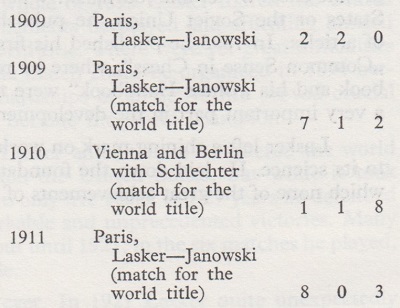

Dawid Markelowicz Janowsky (born 1868) was the last of the unsuccessful challengers for Lasker’s world championship title (Berlin, November-December 1910, a severe defeat). It is, or should be, well known that the two players’ ten-game match in Paris the previous year had not been for the world title, contrary to the assertions of such historical analphabets as Jonathan Speelman (The Observer Review section of 19 April 1998, page 13). In that same article Speelman gave a position from a familiar game in the match, and wrote, ‘I had never seen it before’. The position was incorrect.

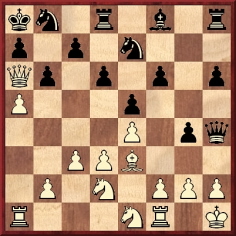

There follow some neglected Janowsky combinations from off-hand play:

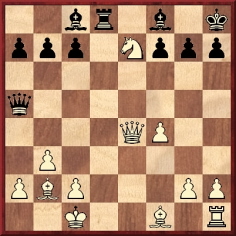

From a knight’s odds game between D. Janowsky and S. David, Paris, 1891 or 1892. 19 Bxg7+ Kxg7 20 Rxh7+ Kxh7 21 f6+ Kh8 22 Qh5+ and mate in two.

Source: Deutsche Schachzeitung, February 1892, pages 50-51.

Janowsky v N.N., Paris, 1892

Play went: 16 Qxa7+ Kxa7 17 axb6+ Kb7 18 Ra7+ Kc6 19 Rxc7+ Kb5 20 Nc2 (20 c4+ would have saved a move.) 20…Nec6 21 c4+ Ka6 22 Ra1+ Na5 23 Nb4 mate.

Source: Deutsche Schachzeitung, May 1892, page 152.

The position below is also from a Paris game, which Janowsky (White) played blindfold:

1 Nxg6 Qxg6 2 Bxf5 Qxf5 3 Qxg8+ Bxg8 4 Rxe7+ Kf8 5 Rxd8 mate.

Source: Deutsche Schachzeitung, November 1893, page 345.

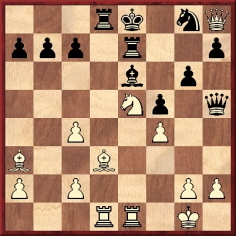

Friedman v Janowsky, Paris, 1894

1…h4 2 Nxd4 Ng3+ 3 hxg3 hxg3+ 4 Kg1 Bxd4+ 5 Rf2 Bxf2+ 6 Qxf2 Rd1+ 7 Qf1 Rh1+ 8 Kxh1 Rxf1 mate.

Source: BCM, September 1894, page 355 and November 1894, page 452.

Dawid Janowsky

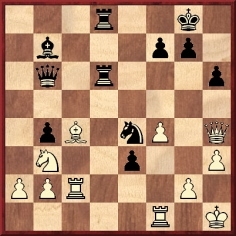

Robino v Janowsky, Paris

1…Bf5 2 Nxf5 Qd2+ 3 Kb1 Qd1+ 4 Bc1 Qxc1+ 5 Kxc1 Ba3+ 6 Kb1 Rd1 mate.

Source: La Stratégie, 15 April 1898, page 118.

Coulomzine v Janowsky, Paris

29…Rg6 30 Kh2 Nd2 31 Rg1 e2 32 Qxd8+ Qxd8 33 Rxd2 Qxd2 34 Nxd2 Rxg2+ 35 Rxg2 e1(Q) 36 Re2 Qh1+ 37 Kg3 Qg1+ 38 Kh4 g5+ 39 Kh5 gxf4 40 Re5 and Black mated in three moves.

Source: La Stratégie, 15 November 1898, page 344. Typically complex Janowsky play, although various short-cuts would have been possible (31…Rxg2+, 33…Qh4 and 39…Qg3).

Janowsky was White in this position from a game at the Manhattan Chess Club, New York. He played 1 Na6+ Ka8 2 Nxc7+ Kb8 3 Na6+ Ka8 4 Rb7 e2 5 Rb8+ Rxb8 6 Nc7 mate.

Source: American Chess Bulletin, March 1918, page 69.

Dawid Janowsky

A specimen of his play in a consultation game:

Dawid Janowsky – Herbert Edward Dobell, Mackeson and Watt

Hastings, 1 September 1897

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 Re1 Nd6 6 Nxe5 Be7 7 Bd3 Nxe5 8 Rxe5 O-O 9 Nc3 Bf6 10 Re3 g6 11 b3 Ne8 12 Ba3 d6 13 Nd5 Bg5 14 f4 Bh6 15 Bb2 Be6 16 Qf3 c6 17 Nc3 d5

18 f5 d4 19 fxe6 fxe6 20 Qh3 Bxe3+ 21 dxe3 dxc3 22 Qxe6+ Kh8 23 Bxc3+ Ng7 24 Rd1 Qe8 25 Qh3 Rd8 26 Qh6 Rd7 27 h3 b5 28 Rd2 Kg8 29 e4 Qe7 30 Kh1 Qc5 31 Bb2 Nh5 32 Kh2 Rdf7 33 Be2 Nf4 34 Bg4 Qb4 35 Rd4 Qe1 36 Rd7 Rxd7 37 Bxd7 Rf7 38 Be8 Qxe4 39 Bxf7+ Kxf7 40 Qxh7+ Ke8 41 Qh8+ Kd7 42 Qd4+ Qxd4 43 Bxd4 a6 44 g4 Ke6 45 h4 and White won.

Source: BCM, October 1897, pages 395-396. Janowsky played four games simultaneously against teams of three players.

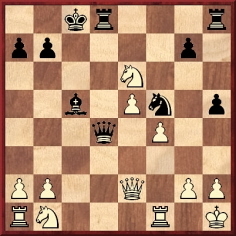

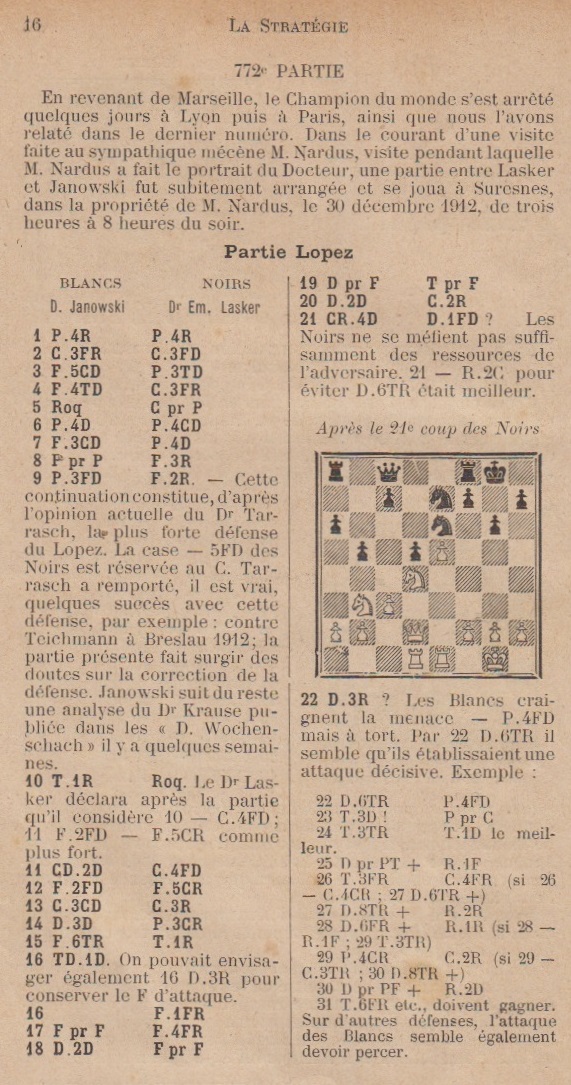

Now a sample of Janowsky’s annotations to one of his games:

Georg Marco – Dawid Janowsky

Sixth match game, S.S. Pretoria, 13 June 1904

King’s Gambit Declined

1 e4 e5 2 f4 Bc5 3 Qf3 (An innovation meriting consideration. [In fact, 3 Qf3 was played twice by Charousek in 1896, against Showalter and Maróczy.]) 3…Nc6 4 c3 d6 5 Bc4 Nf6 (5…Be6 was stronger.) 6 d3 O-O (Premature, in view of the ease with which White sets up a king’s side attack. Here too 6…Be6 would be much better.) 7 f5 (Hemming in the enemy queen’s bishop and threatening g4, followed by h4.) 7…d5 8 Bb3! (8 Bxd5 Nxd5 9 exd5 Ne7 10 g4 Qxd5, etc. and 8 exd5 e4 9 dxe4 Ne5 10 Qe2 Nxc4 11 Qxc4 Nxe4, etc. would be to White’s disadvantage.) 8…dxe4 9 dxe4 Qd6 10 Bg5 (With 10 g4 he could have put his opponent in a very tricky position.) 10…h6 11 Bxf6 (The reply to 11 Bh4 would have been 11…Rd8.) 11…Qxf6 12 Nd2 Rd8 (Taking possession of the open file and having in mind the possibility of being able, if necessary later on, to escape with the king via f8 and e7.) 13 O-O-O a5 (To set up a counter-attack and chase the bishop away from the very awkward diagonal which it occupies.) 14 h4 (In positions of this kind there is rarely time to defend, and victory goes to the player who can attack the fastest.) 14…a4 15 Bc2 b5 16 Ne2 b4 17 g4 bxc3 (Too soon. 17…Ba6, threatening 18…Bxe2, followed by 19…bxc3, would have been much stronger.) 18 Nxc3 (Forced, for if 18 bxc3 then 18…Ba3+, etc.) 18…Nd4 19 Qg2 a3 20 g5 (20 b3 would be more solid.) 20…axb2+ 21 Kb1 Qc6 22 gxh6 (He has no time to play 22 f6 because of 22…Bb4.) 22…Qxh6 23 Nb3 Ba3 24 Nb5 (A tempting move, the consequences of which White did not examine sufficiently closely.)

24…Nxb5 (The attack he obtains provides ample compensation for the sacrifice of the exchange.) 25 Rxd8+ Kh7 26 Rd3 (If 26 Qg3 then 26…Rb8, threatening mate in a few moves by 27…Qc1+. After 27 R8d1, Black wins with 27…Qc6.) 26…Rb8 27 Qg5 (He was threatened with 27…Qc1+ 28 Rxc1 bxc1(Q)+ 29 Nxc1 Nc3+ and mate next move.) 27…Ba6 28 Nd2 Bc5 29 Rhh3 Nd4 30 Rb3 (After 30 Rdg3 Bb4 31 Nb3 Nxc2 32 Kxc2 c5 the loss of a piece is inevitable.) 30…Nxb3 31 Bxb3 f6 32 Qxh6+ (If 32 Qg2 then 32…Bb4, etc.) 32…Kxh6 33 Kxb2 (Material is now level, but Black has the better pawns, two bishops and a superior position.) 33…Rd8 (Decisive.) 34 Kc2 (If 34 Nf3 Kh5, etc., and if 34 Nc4 Rd4, etc.) 34…Bb4 35 Nb1 Bb7 36 White resigns. (His e-, f- and h-pawns cannot be defended.)

Source: La Stratégie, 21 September 1904, pages 263-264.

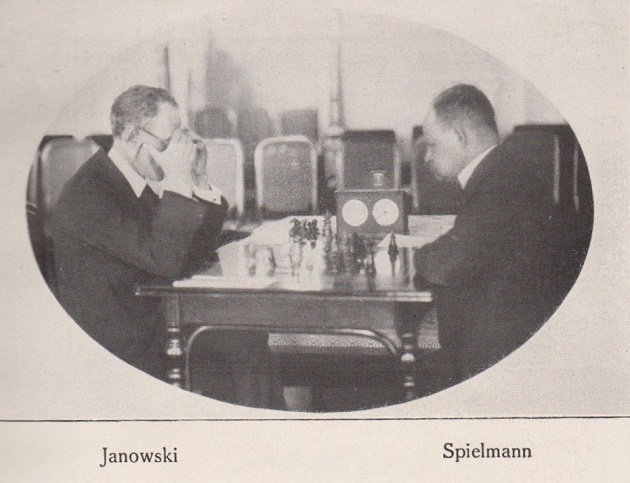

From the Marienbad, 1925 tournament book (see C.N. 9844)

Janowsky was active in chess play until the end. An onlooker at the 1925 Marienbad tournament wrote on page 295 of the July 1925 BCM: ‘Janowsky, gaunt, cadaverous, but with a ready smile which lights up his whole face, goes up to the two or three ladies who sit there waiting, and makes one of his many little witticisms about the other players. “Have you seen so and so? He sway to and fro, to and fro. If he do it much more, I tell him he make me sea-sick”.’

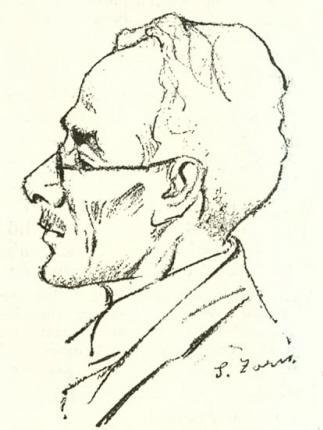

Dawid Janowsky (Wiener Schachzeitung, April 1926, page 106)

At Semmering, 1926 Janowsky was still winning remarkable games, including one against Rubinstein. He died on 15 January 1927 in Hyères (France). The Wiener Schachzeitung (February 1927, page 30) described him as ‘one of the greatest masters of the royal game’. Page 191 of Ludwig Bachmann’s Schachjahrbuch 1927 called him a genius. The obituary writer in L’Echiquier (January 1927, page 552), who had seen him a few months previously in Ghent, reported on the ‘sunken eyes behind large spectacles’ of a master who had been ‘one of the greatest players of his time’. John Keeble noted on pages 103-104 of the March 1927 BCM that Janowsky had arrived in Hyères in December 1926 for a tournament due to begin there the following month. He was diagnosed as being in the final stage of tuberculosis. In Keeble’s words, Janowsky ‘was absolutely without means and in a dying state. A lonely man (he had never married), no relatives near to him, no religion, no income and apparently no friends, for he was not really a sociable man to make them. What a sad end to a successful career devoted almost wholly to chess.’

Dawid Janowsky

With minor differences the above article appeared at the Chess Café in 1998.

C.N. 59 expressed appreciation for Janowsky and gave three of his games from Semmering, 1926: against Kmoch (power of the bishop pair), Rosselli del Turco (a fortunate attacking victory) and Rubinstein (an agile knight in the endgame).

On page 35 of Chernev’s fine book Capablanca’s Best Chess Endings we learn that Janowsky ‘never opened a chess book in his life’.

Presumably this is not to be taken literally, but is there any truth at all in the claim?

(616)

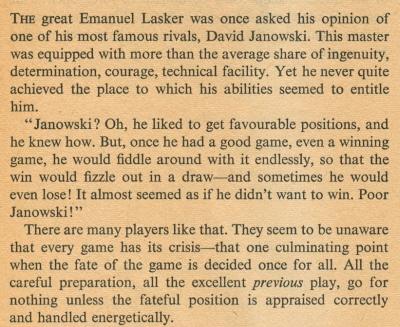

The December 1901 BCM (pages 492-493) quotes from Lasker’s Manchester Evening News column of 20 November:

‘[Janowsky] is one of the great chess matadors ... He is a typical Parisian in style and appearance. He has lively eyes, black moustache and hair, and manages his conversation in English wonderfully well in spite of the meagreness of his stock of perhaps less than 120 words ...’

Some ten years later the same magazine (February 1911, page 60) quoted from the Berliner Zeitung a rather more penetrating analysis by the world champion:

‘This, in my judgement, is the Janowsky problem. His brain is stored with tactical ideas in myriad forms. He has them arranged and possesses the power to mobilize them and bring them to bear on any given position. If success is to be reached by any combination lying fathoms deep in the position, his tireless energy and creative fancy will find it and fashion it. But has he the presentiment necessary to detect the gradual grouping of the factors of such a position? Has he more than the energetic and teeming brain of the tactician; is he a strategist in addition? This last demands intellectual qualities rarely found in prodigal temperaments ... If the strategist preserve his intellectual energies, he invariably wins against the tactician.’

(1109)

A noteworthy comment by Janowsky appears on page 71 of the April 1921 American Chess Bulletin. Annotating the fifth game in the 1921 world championship match, he writes after 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6:

‘Dr Lasker, in his chess magazine, made the following remark on one of my match games with Frank Marshall: “Why should one develop the knight at d7, blocking his bishop, while that knight can be developed at c6?” I quite agree with him. Strange to say, all the great masters in their older days play against their own theory. They evidently miss the power of conviction which is the characteristic of youth.’

(1429)

What passage by Lasker did Janowsky have in mind?

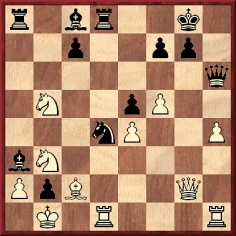

Dawid Janowsky – Géza Maróczy

Munich, 27 July 1900

Albin Counter-Gambit

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 d4 4 e4 Nc6 5 Bf4 Nge7 6 Bg3 h5 7 h3 g5 8 h4 g4 9 Nd2 Ng6 10 f4 Be7 11 Bd3 Nxh4 12 Qe2 Ng6 13 e6 h4 14 Qxg4 Bxe6 15 f5 Bc8 16 Bh2 Nge5 17 Qe2 Nxd3+ 18 Qxd3 Nb4 19 Qb3 a5 20 Nh3 a4 21 Qd1 Nd3+ 22 Kf1 Nxb2 23 Qg4 Ra6 24 Nf4 Kf8 25 Nd5 Rc6 26 Be5 Rg8 27 Qh5 Bg5 28 Nf3 Nxc4 29 f6 Ne3+ 30 Nxe3 Bxe3 31 Rd1 Bg4 32 Qxh4 Bxf3 33 gxf3 Rc2 34 Bxd4 Qa8

35 Rd3 Qa6 36 White resigns.

The Munich, 1900 tournament book (page 50) gives the conclusion of the game as 35 Rd3 Qa6 36 White resigns, but a few other sources have mistakenly claimed that Janowsky won in brilliant style. The earliest we know of is P. Wenman’s One Hundred Chess Gems (first published in 1939). On pages 42-43 he affirmed that the finish had been 35 Ba7 Bxa7 36 Qh6+ Ke8 37 Qg7 Rf8 38 Qxf8+ Kxf8 39 Rh8 mate. Wenman also gave that fictitious conclusion on page 75 of Learn to Play Chess (1946). See CHESS, April 1953, page 126 and May 1953, page 151 for further details, as well as the September 1979 issue of the Australian magazine Chess Player’s Quarterly (pages 69 and 71), which has an article entitled ‘The Game That Never Was’ by Mike Winslade.

Was Wenman (described by The Companion as ‘the problem world’s most notorious plagiarist’) the first to tamper with the Janowsky-Maróczy game and if so was it an isolated offence in his game anthologies?

One Hundred Chess Gems is a curious work. Whereas Capablanca’s play is featured only once (his loss to Lilienthal), there are two games by Wenman himself (a win and a draw in the battle for supremacy at ‘the Bristol and Clifton Club Championship’).

Wenman churned out many books which, despite (?) the bad contents, had good sales and gained him a certain amount of fleeting fame. But by the time he died, in 1972, he had been consigned to oblivion and was ignored by the obituarists. A cautionary tale.

(1652)

In Robert Byrne’s chess column on page 14 of the International Herald Tribune of 21 June 1988 (a feature about Janowsky) there are three factual errors in half a sentence:

‘'His crushing failure – one victory, seven defeats, one* draw – in his 1909 world championship* match with Emmanuel* Lasker did not deter him from raising the money for a second attempt the following year.’

The asterisks mark the mistakes.

(1675)

The scores of speed games from yesteryear are scarce, but the American Chess Bulletin of April 1918 (page 78) published one between Marshall and Janowsky, played at 20 seconds per move:

Frank James Marshall – Dawid Janowsky

New York, 1918

Queen’s Pawn Game

(1848)

In section 33 of Chess Fundamentals Capablanca annotated the game Janowsky v Kupchik, Havana, 1913, which began 1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e3 Nbd7 6 Bd3 dxc4 7 Bxc4 Nb6. At this point the Cuban says that the normal course, 7...O-O, followed by 8...c5, is more reasonable and he recommends as a ‘beautiful illustration of how to play White in that variation’ the game between Janowsky and Rubinstein, St Petersburg, 1914.

Since that encounter began 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 c5 3 c4 e6 4 e3 Nf6 5 Bd3 Nc6 6 O-O dxc4 7 Bxc4 a6 8 Nc3 b5 9 Bd3 cxd4 10 exd4 Nb4 and was won by Black, who did not castle until his 17th move, it would seem that Capablanca was thinking of a different game. But which one?

(2122)

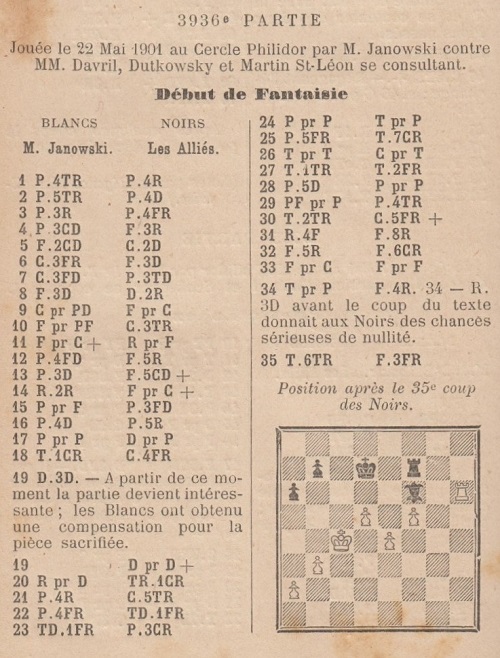

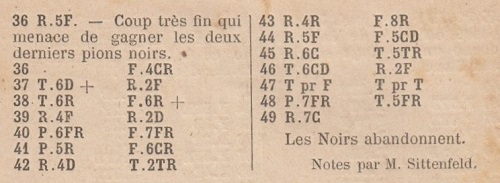

Here is a game in which Dawid Janowsky, one of the world’s leading players at the time, played a ‘fantasy opening’. The allies were Davril, Dutkowsky and Martin St-Léon.

Dawid Janowsky – Allies

Paris, 22 May 1901

Irregular Opening

1 h4 e5 2 h5 d5 3 e3 f5 4 b3 Be6 5 Bb2 Nd7 6 Nf3 Bd6 7 Nc3 a6 8 Bd3 Qe7 9 Nxd5 Bxd5 10 Bxf5 Nh6 11 Bxd7+ Kxd7 12 c4 Be4 13 d3 Bb4+ 14 Ke2 Bxf3+ 15 gxf3 c6 16 d4 e4 17 fxe4 Qxe4 18 Rg1 Nf5 19 Qd3 Qxd3 20 Kxd3 Rhg8 21 e4 Nh4

22 f4 Raf8 23 Raf1 g6 24 hxg6 Rxg6 25 f5 Rg2 26 Rxg2 Nxg2 27 Rh1 Rf7 28 d5 cxd5 29 cxd5 h5 30 Rh2 Nf4+ 31 Kc4 Be1 32 Be5 Bg3 33 Bxf4 Bxf4 34 Rxh5 Be5 35 Rh6 Bf6 36 Kc5 Bg5 37 Rd6+ Kc7 38 Re6 Be3+ 39 Kc4 Kd7 40 f6 Bf2 41 e5 Bg3 42 Kd4 Rh7 43 Ke4 Be1 44 Kf5 Bb4 45 Kg6 Rh4 46 Rb6 Kc7

47 Rxb4 Rxb4 48 f7 Rf4 49 Kg7 Resigns.

Source: La Stratégie, 15 June 1901, pages 172-173.

(2272)

Dawid Janowsky – N.N.

Paris, 1895

(Remove White’s queen’s knight.)

17 Re5 Qf2 18 Rg5+ Bxg5 19 Qxg5+ Kh8 20 Qxf6+ Rxf6 21 Bxf6 mate.

Source: La Stratégie, 15 April 1895, pages 115-116.

(2500)

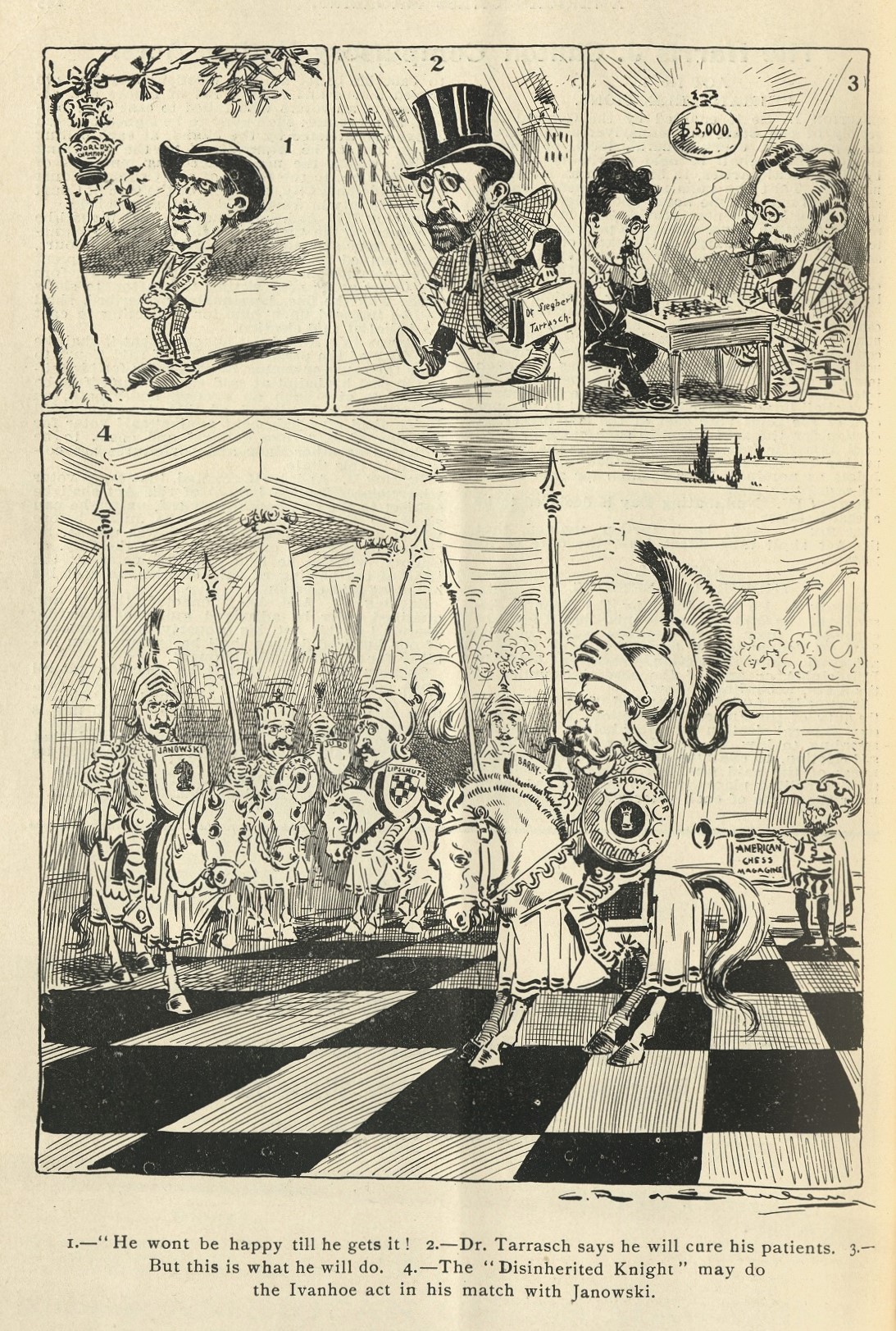

From page 302 of the American Chess Magazine, January 1899 (acknowledgement: the Cleveland Public Library).

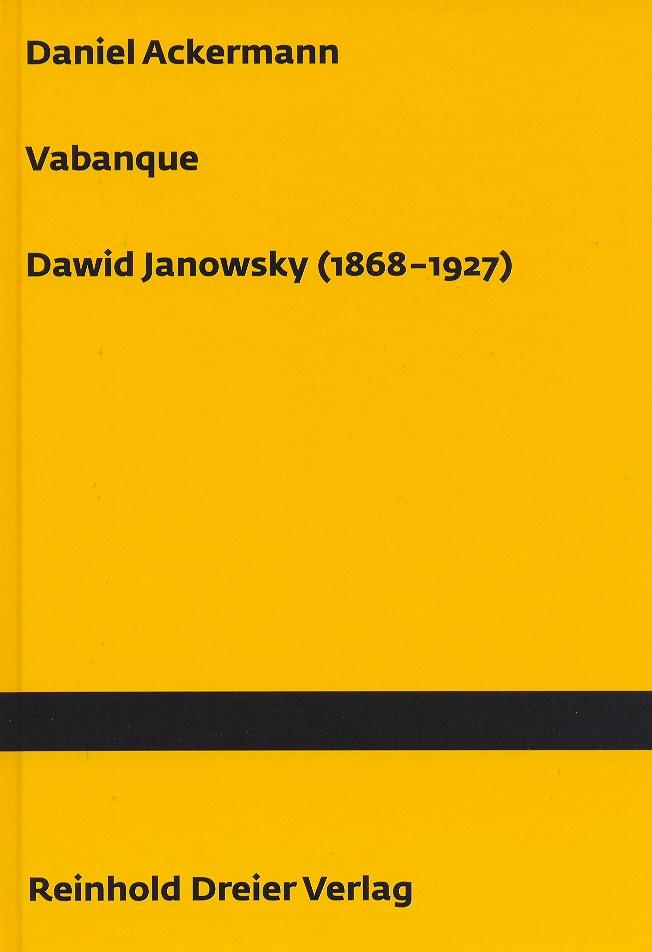

As shown in the American Chess Magazine, 1898-99 and in Vabanque Dawid Janowsky 1868-1927 by D. Ackermann (Ludwigshafen, 2005), the results of the contests between Janowsky and Showalter were as follows:

18 November 1898 - 12 January 1899: Janowsky +7, Showalter +2, Drawn 4;

15-20 March 1899: Janowsky +2, Showalter +4, Drawn 0;

29 March-7 April 1899: Janowsky +2, Showalter +4, Drawn 1.

Some general comments on the relative strength of bishops and knights were made by Janowsky when annotating his win over Napier at Hanover, 1902. After Black’s 42nd move he wrote:

‘The two knights have been completely immobilized. The superiority of two bishops against two knights is demonstrated once again in striking form. This matter has been discussed in the chess press very frequently; some (Dr Tarrasch, for example) prefer the two bishops while others (Mr Chigorin) prefer the two knights. Some theoreticians have declared that everything depends on the position; that does not settle the issue since when a result depends on the position the superiority or inferiority of the two bishops is not demonstrated at all. In my opinion, having two bishops against two knights in a more or less equal position is a significant advantage.’

Source: La Stratégie, 17 September 1902, page 283.

(2501)

See also Raking Bishops.

From W.E. Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (published in three ‘units’, the first two in 1934 and the third the following year). The figure refers to the item number, given that the pages were unnumbered:

52. ‘Once in chatting with Janowsky at Lake Hopatcong, he referred to Maróczy as the gentle iron-man of Hungary, which was accurate as to both specifications.’

Dawid Janowsky – Adolf Albin

Masters’ tournament, Paris, 22 October 1902

Dutch Defence

(Annotations by Janowsky)

1 d4 f5 (We prefer the reply 1…d5.) 2 c4 e6 3 e3 Nf6 4 Bd3 Nc6 (A new move in this position, but hardly to be recommended, in our view. 4…b6 is generally played here.) 5 Nc3 Bb4 6 Nf3 O-O 7 O–O Bxc3 8 bxc3 d6 9 d5 exd5 (It is hard to see why Black undoubled his opponent’s pawns. 9…Ne7 at once would be better.) 10 cxd5 Ne7 11 c4 Ng6 12 Bb2 Ng4 13 Nd4 N6e5 14 Be2 (Black’s attack is more apparent than real, which is why White can afford to lose a tempo to preserve his bishop pair. He will win back time by chasing away the enemy knights.) 14…Qe7 15 h3 Nh6 (15…Nf6 would be preferable.) 16 f4 (As a rule, a player should not weaken his own pawns, but the present position is an exception. This proves that chess cannot always be played by following principles; as Dr E. Lasker says, something more is required … A closer examination of the position shows that the text-move blocks the black f-pawn and consequently impedes the movement of the queen’s bishop. Moreover, it allows the rook to come to g3, whence it will, in conjunction with the bishop at b2, strongly support the attack on the castled king.) 16…Ng6 17 Rf3 Bd7 18 Qb3 b6 19 Qc3 Rf7 20 Rg3 Re8

21 Kh2 (As will be seen later, this move is necessary and decisive.) 21…a5 22 Bh5 Rf6 (It is now clear that if White had not previously played his king to h2 Black would be able to respond with 22…Qh4, a move which is not possible now because of 23 Bxg6 and if 23…Ng4+ then 24 Rxg4, followed by 25 Bxf7+, etc.) 23 Qd3 Rf7 24 Rf1 Qh4 (This is immediately fatal, but whatever he does his game cannot be defended for long.) 25 Bxg6 hxg6 (See the note to move 22.) 26 Nf3 Qh5 (Either 26…Qe7 or 26…Qd8 was forced.) 27 Kg1 (Decisive. 27 Rg5 would be bad because of 27…Ng4+) 27…Ng4 (The only move allowing Black to get out of his predicament momentarily. Perhaps at move 24 Black thought that he had time now to play 27...Rfe7, but that would also be bad, because of 28 Rg5 Rxe3 29 Qd4.) 28 hxg4 fxg4 29 Ng5 Rfe7 30 e4 Qh4 31 Re3 Bc8 32 g3 Qh5 33 Rf2 Resigns. (The black queen is threatened again, but this time has no means of escape.)

Source: La Stratégie, 21 January 1903, pages 3-4 (our translation into English).

(2788)

Daniel F.M. Starbuck – N.N.

Occasion?

Philidor’s Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 Bg4 4 dxe5 Bxf3 5 Qxf3 dxe5 6 Bc4 Nf6 7 Qb3 Qe7 8 Nc3 b6 9 Bg5 Nbd7 10 Nd5 Nc5 11 Qb5+ Qd7 12 Bxf6 Qxb5 13 Bxb5+ Nd7 14 Nxc7 mate.

The score is taken from page 77 of L’ABC des échecs by N. Preti (Paris, 1906), a 566-page volume whose coverage of the main openings was revised by Janowsky. We note in passing that when discussion of the Sicilian Defence began on page 355, the move 1...c5 was given a question mark.

(2936)

A letter from John Keeble on pages 103-104 of the March 1927 BCM stated that Janowsky ‘was buried in the Hyères cemetery. His grave is in the north-west corner of the cemetery, high up on one of the hills to the north of Hyères’. We should like further information about Janowsky’s resting place.

On page 137 of Mille et une anecdotes (Tirana, 1994) Claude Scheidegger stated that the following epitaph appeared on Janowsky’s tombstone:

‘Nous sommes les pions de la mystérieuse partie d’Echecs jouée par Dieu. Il nous déplace, nous arrête, nous pousse encore, puis nous lance un à un dans la boîte du Néant.’

Scheidegger did not mention that the quote comes from Omar Khayyám. Various English-language translations exist, and readers are referred to, for instance, pages 144-146 of A Short History of Chess by Henry A. Davidson and pages 38-43 of Chess Pieces by N. Knight. On page 11 of King, Queen and Knight N. Knight and W. Guy commented:

‘This quatrain from the Persian poet who was born in the eleventh century has probably become the best-known chess quotation in the English language.’

(3067)

A description of Dawid Janowsky was published on pages 215-216 of the American Chess Magazine, November 1898:

‘Janowsky is a smaller man than his pictures would give one the impression. Very dark complexion, heavy eyebrows, but large and frank eyes; a most cordial although at first diffident manner, in action showing a confidence in himself that indicates the source of his success.

He speaks only French and German, a few words of English, not enough to permit of conversation; but his manner is so pleasant that lack of conversation without an interpreter seemed not a bar to cordiality.

Janowsky spoke freely of his colleagues among the chess masters of the world, not hesitating to place himself in the niche he believed he fitted. He stated he classed Harry N. Pillsbury, the American champion, and Emanuel Lasker, the world’s champion, above Dr Tarrasch, and thinks that he and the champion are about equal in strength just below the other two. He thinks Lasker is a sounder player than Pillsbury, but Pillsbury possesses greater powers of combination than the world’s champion. Despite his modest admission that he considers the others above him, he said he did not fear any of them, and would not be averse to matches with them.’

Later in his career, Janowsky was ‘reported to have said’ (to repeat the easy-going expression of William Winter on page 48 of Kings of Chess), “There are only three chess masters, Lasker, Capablanca, and the third I am too modest to mention”. Is anything more known about this alleged remark?

A tribute to Janowsky’s skill appeared on page 395 of the March 1899 American Chess Magazine. From 23 January to 7 February that year he had played a ‘series of exhibition match games against 15 of the leading metropolitan players at the Manhattan Chess Club’, including Richardson, Hanham, Delmar, D.G. Baird, de Visser, Lipschütz and Hodges. Janowsky scored +14 –0 =1, ‘a performance that is quite on a par with those of Champion Lasker on the occasion of his visit to this country’. The magazine added: ‘A feature was the rapidity of the French expert’s play, and often it happened that he took an hour less than his opponent.’

Can a reader find any of the game-scores in local newspapers of the time?

(3173)

The request at the end of C.N. 3173 for the scores of Janowsky’s 15 exhibition games at the Manhattan Chess Club in 1899 has been answered by Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany), who has kindly supplied the complete set, each game having been published in the New-Yorker Staats-Zeitung the day after play.

Dawid Janowsky – L. Schmidt

Exhibition game (1), New York, 23 January 1899

Dutch Defence

1 d4 f5 2 c4 Nf6 3 Nc3 e6 4 e3 Be7 5 Bd3 O-O 6 Nf3 Qe8 7 Qc2 Nc6 8 a3 a6 9 O-O b6 10 e4 fxe4 11 Nxe4 Nxe4 12 Bxe4 Qh5 13 d5 Nd8 14 dxe6 Rb8 15 exd7 Bxd7 16 Rd1 Be6 17 b3 Bd6 18 Bb2 Nf7 19 Re1 Bg4 20 h3 Bxh3 21 gxh3 Qxh3 22 Re3 Bf4 23 Bf5 Qh4 24 Kg2 g6 25 Be6 Resigns.

Philip Richardson – Dawid Janowsky

Exhibition game (2), New York, 24 January 1899

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 Re1 Nd6 6 Nxe5 Be7 7 Bd3 O-O 8 Nc3 Nxe5 9 Rxe5 a6 10 b3 Ne8 11 Bb2 d5 12 Qf3 Bf6 13 Re2 Be6 14 Rae1 Qd7 15 h3 Nd6 16 Nd1 Bxb2 17 Nxb2 Rae8 18 c3 f5 19 Bc2 Ne4 20 Nd3 g5 21 Ne5 Qg7 22 d4 c5 23 Qe3 Rc8 24 Bxe4 dxe4 25 f3 cxd4 26 cxd4 Bd5 27 fxe4 Bxe4 28 Rd2 Bd5 29 Qg3 h6 30 Kh2 b5 31 h4 b4 32 h5 Rc3 33 Qf2 g4 34 Qh4 Re8 35 Ng6 Qc7+ 36 Ne5 g3+ 37 Kg1 Qg7 38 Rf1 Be4 39 Qf4 Qg5 40 Nd7 Kg7 41 Qxg5+ hxg5 42 Nc5 Bc6 43 d5 Bb5 44 Ne6+ Kf6 45 Rfd1 f4 46 h6 Rh8 47 Nd4 Bd7 48 Re1 Rxh6 49 Rde2 Rd3 50 Nc6

50…Rxd5 51 Ne7 Rd3 52 Ng8+ Kg6 53 Nxh6 Kxh6 54 Re4 a5 55 Re5 g4 56 Kf1 f3 57 Rxa5 Rd2 58 Rc1 Rf2+ 59 Kg1 Rxg2+ 60 Kf1 Rh2 61 Ra6+ Kg5 62 Rc5+ Bf5 63 White resigns.

Dawid Janowsky – Charles B. Isaacson

Exhibition game (3), New York, 25 January 1899

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 d4 Be7 6 Qe2 Nd6 7 Bxc6 dxc6 8 dxe5 Nf5 9 Rd1 Bd7 10 e6 fxe6 11 Ne5 Bd6 12 Qh5+ g6 13 Nxg6 hxg6 14 Qxh8+ Kf7 15 Qh7+ Ng7 16 Rd3 e5 17 Rf3+ Bf5 18 g4 e4 19 gxf5 exf3 20 Qxg6+ Kg8 21 f6 Resigns.

Dawid Janowsky – James Moore Hanham

Exhibition game (4), New York, 26 January 1899

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 d4 Nd6 6 dxe5 Nxb5 7 a4 d5 8 axb5 Ne7 9 Bg5 Be6 10 Nd4 Qd7 11 Nc3 Ng6 12 Nxe6 fxe6 13 Qd4 b6 14 b4 Be7 15 Be3 Nxe5 16 Bf4 Ng4 17 Qxg7 Bf6 18 Qxg4 Bxc3 19 Ra3 Bxb4 20 Re3 O-O-O 21 Bxc7 Kxc7 22 Qxb4 d4 23 Qc4+ Kb8 24 Rxe6 Rhg8 25 Qe2 Rg5 26 Re5 Rdg8 27 g3 h5 28 Re1 h4

29 Qf3 hxg3 30 Rxg5 gxf2+ 31 Kxf2 Rxg5 32 Qf4+ Qc7 33 Re8+ Kb7 34 Qe4+ Resigns.

A. Schroeter – Dawid Janowsky

Exhibition game (5), New York, 27 January 1899

Queen’s Pawn Opening

1 d4 d5 2 e3 Nf6 3 Bd3 c5 4 c3 Nc6 5 f4 e6 6 Nd2 Bd6 7 Nh3 Qc7 8 Nf3 b6 9 Bd2 Bb7 10 Nf2 O-O 11 Rc1 Ne7 12 g4 Ne4 13 Bxe4 dxe4 14 Ng5 h6 15 Ngh3 Ng6 16 g5 Nh4 17 Qh5 Nf3+ 18 Kd1 hxg5 19 Nxg5 Nxg5 20 Qxg5 f6 21 Qh5 e5 22 Rg1 Qf7 23 Rg6 Qc4 24 Rh6 gxh6 25 Qg6+ Kh8 26 Qxh6+ Kg8 27 Qg6+ Kh8 28 Qh6+ Kg8 29 Qg6+ Kh8 30 Qh5+ Kg7 31 Kc2 Rf7 32 fxe5 fxe5 33 dxe5

33…Qe6 34 Rg1+ Kf8 35 exd6 Qxd6 36 Rg6 Qd5 37 Qh6+ Ke7 38 Qh4+ Kd7 39 c4 Qxc4+ 40 Bc3 Qe2+ 41 Kc1 Qxe3+ 42 Bd2 Qxf2 43 Qg4+ Qf5 44 Qg3 Qf1+ 45 Kc2 Qd3+ 46 White resigns.

Dawid Janowsky – Eugene Delmar

Exhibition game (6), New York, 29 January 1899

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Nf6 5 Bd3 Nbd7 6 Nf3 Nxe4 7 Bxe4 Nf6 8 Bd3 Bd6 9 O-O h6 10 Ne5 O-O 11 Qe2 c5 12 dxc5 Bxc5 13 Rd1 Qc7 14 Ng4 Nxg4 15 Qxg4 e5 16 Qg3 Qb6 17 Bd2 f5 18 Qxe5 Bxf2+ 19 Kh1 Bd4 20 Bc4+ Kh7 21 Qe7 Bc5 22 Qe2 Bd7 23 Bc3 Bc6 24 Bd5 Rae8 25 Qh5 Re7 26 Rd3 Bb5 27 Rg3 Bf2 28 Rh3 Qc5

29 Bxg7 Qxd5 30 Qxh6+ Kg8 31 Qh8+ Kf7 32 Qxf8+ Ke6 33 Qc8+ Bd7 34 Rh6+ Resigns.

M. van der Werra – Dawid Janowsky

Exhibition game (7), New York, 30 January 1899

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Bd3 Nc6 6 c3 d5 7 exd5 Qxd5 8 Qf3 Nxd4 9 Qxd5 Nxd5 10 cxd4 Nb4 11 Ke2 Nxd3 12 Kxd3 b6 13 Be3 Ba6+ 14 Kd2 Be7 15 Nc3 O-O 16 Rhd1 f5 17 f3 Bd6 18 f4 Rad8 19 Ke1 g5 20 g3 gxf4 21 gxf4 Rf7 22 Kf2 Rg7 23 Rg1 Rg6 24 Rg3 Be7 25 Rxg6+ hxg6 26 Ne2 Kf7 27 Ng1 Bh4+ 28 Kf3 Rh8 29 Rc1 Bb7+ 30 Ke2 Be7 31 h3 Bd6 32 Rc3 Bd5 33 a3

33…Rh4 34 Nf3 Bxf3+ 35 Kxf3 Rxh3+ 36 Kg2 Rh4 37 Kf3 g5 38 fxg5 Rh3+ 39 Ke2 f4 40 Bf2 Rxc3 41 bxc3 Bxa3 42 Kf3 Bd6 43 c4 Kg6 44 c5 bxc5 45 dxc5 Bc7 46 Kg4 e5 47 c6 a5 48 Bc5 e4 49 Bd4 f3 50 Be3 a4 51 White resigns.

Dawid Janowsky – O.M. Bostwick

Exhibition game (8), New York, 31 January 1899

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e5 Nfd7 6 Bxe7 Qxe7 7 Nb5 Nb6 8 c3 a6 9 Na3 N8d7 10 f4 c5 11 Nc2 O-O 12 Nf3 f6 13 Bd3 c4 14 Be2 Rf7 15 O-O f5 16 Ne3 Rb8 17 Qd2 Na8 18 Bd1 b5 19 Bc2 Nc7 20 g4 g6 21 Kh1 Kh8 22 Rg1 Bb7 23 Rg3 Rg8 24 Rag1 fxg4 25 Rxg4 Rgf8 26 Ng2 Rg8 27 Ng5 Rfg7 28 Rh4 Nf8 29 Rh6 Bc6 30 Ne3 Be8 31 Ng4 Nd7 32 Rg3 a5 33 Rgh3 Na6 34 Qf2 Rf8

35 Qh4 Rxf4 36 Rxh7+ Rxh7 37 Qxh7+ Qxh7 38 Rxh7+ Kg8 39 Nh6+ Kf8 40 Nxe6 mate.

Dawid Janowsky – David Graham Baird

Exhibition game (9), New York, 1 February 1899

Four Knights’ Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nc3 Nc6 4 Bb5 Bb4 5 O-O O-O 6 d3 d6 7 Bg5 Be6 8 Nd5 Bxd5 9 exd5 Nd4 10 Bc4 h6 11 Bc1 Nf5 12 c3 Ba5 13 Nd2 Nh4 14 g3 Ng6 15 Ne4 Nxe4 16 dxe4 Qf6 17 Qg4 Rad8 18 h4 Kh7 19 Bd3 Bb6 20 Kg2 Nh8 21 f4 Qg6 22 Qf3 f6 23 f5 Qe8 24 g4 Kg8 25 g5 hxg5 26 hxg5 Kf7 27 Rh1 Rg8 28 Rh7 Kf8 29 Bd2 Nf7 30 g6 Ng5 31 Bxg5 fxg5 32 Rah1 Qe7

33 f6 Qxf6 34 Qxf6+ gxf6 35 Rf7+ Ke8 36 Bb5+ c6 37 dxc6 Rxg6 38 Rhh7 a6 39 Ba4 Resigns.

Dawid Janowsky – William M. de Visser

Exhibition game (10), New York, 2 February 1899

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 e6 6 Ndb5 Bb4 7 Nd6+ Ke7 8 Bf4 e5 9 Bg5 Bxd6 10 Nd5+ Ke8 11 Bc4 Be7 12 O-O Nxd5 13 Qxd5 Rf8 14 f4 d6 15 Bxe7 Qb6+ 16 Kh1 Kxe7 17 Rad1 Na5 18 Bb3 Be6 19 Qd3 Nxb3 20 axb3 f6 21 c4 Qc7 22 f5 Bg8 23 Rf2 Rac8 24 Qg3 b5 25 cxb5 Qc1 26 Qd3 Qc5

27 Rc2 Qd4 28 Qf1 Rxc2 29 Rxd4 exd4 30 h4 Rfc8 31 Qd3 R8c5 32 b4 R5c4 33 Qa3 Rc7 34 Qd3 R7c4 35 Kh2 d5 36 e5 fxe5 37 Qg3 Kf6 38 Qg5+ Kf7 39 Qd8 Rc7 40 Qxd5+ Kf6 41 Qxg8 Kxf5 42 Qf8+ Ke6 43 Qg8+ Rf7 44 Qe8+ Re7 45 Qg8+ Rf7 46 Qe8+ Re7 47 Qg8+ Drawn.

Gustav Henschel Koehler – Dawid Janowsky

Exhibition game (11), New York, 3 February 1899

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nc3 Nc6 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 Nf6 6 Ndb5 d6 7 Bf4 e5 8 Bg5 a6 9 Na3 Be7 10 Bxf6 Bxf6 11 Nc4 Be7 12 Nd5 Be6 13 Nxe7 Kxe7 14 Ne3 Qb6 15 Rb1 Qb4+ 16 c3 Qxe4 17 Bd3 Qh4 18 O-O g6 19 b3 d5 20 Re1 Rhd8 21 Qc1 Rac8 22 Qa3+ Ke8 23 Rbd1 f5 24 b4 f4 25 g3 Qf6 26 gxf4 Qxf4 27 Ng2 Qf6 28 b5 axb5 29 Bxb5 Kf7 30 f4 e4 31 Ne3 Ne7 32 c4 d4 33 Ng2 e3 34 Qa7 Bg4 35 Rd3 Bf5 36 Rb3 Be4 37 Nxe3

37…Qh4 38 Ng2 Bxg2 39 Rxe7+ Qxe7 40 Kxg2 Ra8 41 Qb6 Rxa2+ 42 White resigns.

Dawid Janowsky – Gustave Simonson

Exhibition game (12), New York, 4 February 1899

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bf4 Be7 5 Rc1 c6 6 e3 O-O 7 Nf3 Nbd7 8 Bd3 h6 9 h3 Ne8 10 g4 Bd6 11 Bxd6 Nxd6 12 c5 Ne8 13 Bb1 f5 14 g5 hxg5 15 Rg1 e5 16 Nxe5 Nxe5 17 dxe5 Nc7 18 Qh5 Ne6 19 Ne2 Qe7 20 Nd4 Nxc5 21 Rxg5 Ne4 22 Bxe4 dxe4 23 Ke2 Qxe5 24 Rcg1 Rf7 25 Rg6 b6 26 Rh6 Ba6+ 27 Ke1 Qa5+ 28 Kd1 Be2+ 29 Kxe2 Qa6+ 30 Kd2 Resigns.

S. Lipschütz – Dawid Janowsky

Exhibition game (13), New York, 5 February 1899

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e3 O-O 6 Nf3 b6 7 Rc1 c5 8 cxd5 exd5 9 Bd3 Nbd7 10 O-O Bb7 11 Bb1 Ne4 12 Bxe7 Qxe7 13 dxc5 Nxc3 14 Rxc3 bxc5 15 Qc2 g6 16 Rc1 Rac8 17 Qa4 Bc6 18 Qf4 Rb8 19 b3 Rfe8 20 Qh6 d4 21 Nxd4 cxd4 22 Rxc6 Ne5 23 Rc7 Qd6 24 Qf4 d3 25 Qd4 Qxd4 26 exd4 d2 27 Rf1 Rbd8 28 Bc2 Rxd4 29 Bd1 Nd3 30 f3 Nb2 31 Kf2

31…Re1 32 Rxe1 Nd3+ 33 White resigns.

Albert Beauregard Hodges – Dawid Janowsky

Exhibition game (14), New York, 6 February 1899

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 Bb4 6 Bd3 Nc6 7 Nde2 d5 8 O-O d4 9 Nb5 Bc5 10 c3 dxc3 11 Nbxc3 O-O 12 Ng3 Ne5 13 Be2 Qe7 14 Bg5 h6 15 Bxf6 Qxf6 16 Nh5 Qh4 17 g3 Qe7 18 Kg2 Rd8 19 Qc2 Bd7 20 Rae1 Rac8 21 f4 Nc6 22 e5 Nd4 23 Qc1 Bc6+ 24 Kh3 b5 25 Bg4 Qb7 26 Nf6+ gxf6 27 f5 Bg2+ 28 Kh4 exf5 29 exf6 Bf8 30 Bxf5 Nf3+ 31 Kh5 Nxe1 32 Qxe1

32…Bf3+ 33 g4 Rc5 34 Kh4 Rxf5 35 gxf5 Rd4+ 36 Kg3 Rg4+ 37 Kh3 h5 38 White resigns.

Edward Hymes – Dawid Janowsky

Exhibition game (15), New York, 7 February 1899

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Bd3 Nc6 6 Nxc6 bxc6 7 O-O d5 8 Nd2 Be7 9 Re1 O-O 10 e5 Nd7 11 Qh5 f5 12 Nf3 Nc5 13 Ng5 h6 14 Nh3 Qe8 15 Qf3 Ne4 16 Bxe4 fxe4 17 Qg3 Kh7 18 Be3 Rf5 19 Kh1 Qg6 20 Qxg6+ Kxg6 21 g4 Rf7 22 Rg1 Bg5 23 Nxg5 hxg5 24 Rg3 Ba6 25 Rh3 Be2 26 Rh5 Bf3+ 27 Kg1

27…Rf4 28 Bxf4 gxf4 29 Rh3 Rb8 30 b3 d4 31 Rxf3 exf3 32 Rd1 Rb5 33 Rxd4 Rxe5 34 Kf1 Kg5 35 h3 Re2 36 Rc4 e5 37 Rxc6 e4 38 Rc5+ Kg6 39 Rc4 Kf6 40 h4 Ke5 41 Rc5+ Kd4 42 Rc4+ Kd5 43 h5 e3 44 Rxf4 Rxf2+ 45 Ke1 Ke5 46 Rf8 Ke4 47 Re8+ Kf4 48 Rf8+ Kg3 49 Re8 e2 50 Re3 Rf1+ 51 Kd2 Rd1+ 52 White resigns.

The American Chess Magazine (March 1899, page 395) described Janowsky’s performance as ‘one of the finest records ever achieved by a visiting master in this country’.

(3174)

Further to C.N. 3173 above, Giordano Bergamo (Cavareno, Italy) points out that in Tarrasch’s Die moderne Schachpartie (see page 412 or pages 447-448, depending on the edition) a similar remark is attributed to Minckwitz’s father:

‘Es gibt nur drei hervorragende deutsche Dichter: Schiller, Goethe, und den dritten verbietet mir meine Bescheidenheit zu nennen.”

(3175)

Pages 129-131 of The Chess Kid’s Book of Checkmate by D. MacEnulty (New York, 2004) comprise a chapter entitled ‘The Blind Swine Checkmate’. From page 129:

‘The checkmate that follows from the position in this diagram is called the Blind Swine Mate. Perhaps the name comes from the fact that we call a rook on the seventh rank a pig (because there are usually a lot of enemy pawns for the rook to root around in, or maybe it’s because a rook on the seventh hogs the board), and with doubled rooks on the seventh rank, even a couple of blind pigs could find this checkmate. Actually, this pattern got its name from David Janowski (1868-1927), a Polish grandmaster who referred to a pair of rooks on the seventh rank that could not find a mate as “blind swine”. In this pattern, they do find the mate, so maybe we should change the name, but somehow “the sighted swine checkmate” doesn’t sound right.’

The next page of MacEnulty’s book (which, overall, is not quite as poorly written as the above paragraph suggests) has this diagram (no white king) with the caption ‘Blind Swine Mate’:

1 Rxg7+ Kh8 2 Rxh7+ Kg8 3 Rbg7 mate.

From our reading, the term seems to occur mainly in German-language sources. For example, the following entry is on page 44 of Lexikon für Schachfreunde by M. van Fondern (Lucerne and Frankfurt, 1980):

‘Blinde Schweine, von Janowski erfundener Ausdruck; obwohl ein Turm auf der 7. Reihe eine wichtige strategische Funktion erfüllt, können in der Diagrammstellung die verdoppelten Türme kein Matt erzwingen.’

An almost identical definition and diagram are given on page 40 of Grosses Schach-Lexikon by K. Lindörfer (Munich, 1991).

What is known about the origins of this term, and Janowsky’s alleged connection with it?

(3494)

No connection between Janowsky and the term ‘blind pigs’ has yet been found, but the following sourceless assertion is on page 65 of Chess Rules of Thumb by L. Alburt and A. Lawrence (New York, 2003):

‘Nimzowitsch called a pair of rooks on the opponent’s second rank “blind pigs” because they devour everything indiscriminately.’

(3525)

Regarding Janowsky’s alleged use of ‘blind swine’ to describe two rooks on the seventh rank, James Stripes (Spokane, WA, USA) points out that the attribution appeared in V. Vuković’s book The Art of Attack in Chess; see, for instance, page 73 of the 1993 edition published by Cadogan Chess.

Vuković gave this diagram with the caption ‘Blind swine’ and stated:

‘The pair of rooks which “grunt out check” on the seventh rank but cannot get a sight of mate were once nicknamed “blind swine” by Janowski.’

Our correspondent cites two games in which Janowsky could only draw despite having his rooks on the seventh rank: his tenth match-game against Showalter in New York, January 1899 (American Chess Magazine, February 1899, pages 360-361) and his first-round encounter with Marshall at New York, January 1913 (American Chess Bulletin, March 1913, page 54).

(5160)

From page 239 of Point Count Chess by I.A. Horowitz and Geoffrey Mott-Smith (New York, 1960):

‘The ultimate triumph of the open file is to get a rook to the seventh rank, whence it strikes at the enemy pawn base. This “pig” (Spielmann’s epithet) is the more odious when it also menaces the king.’

Can any details be found in Spielmann’s writings?

(6108)

From page 215 of The Golden Treasury of Chess by Francis J. Wellmuth (Philadelphia, 1943):

(7003)

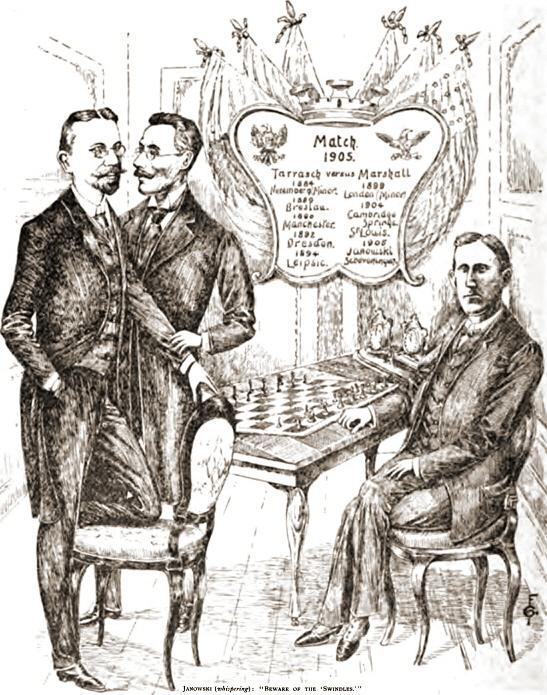

Page 31 of Chess Strategy and Tactics by F. Reinfeld and I. Chernev (New York, 1933) referred to Janowsky’s ‘inordinate and aggressive self-confidence, which gave rise to many amusing incidents. Thus, after the loss of his match against Marshall in 1905, he sent the American master a telegram offering to play him at knight odds!’

Forty years later Chernev still found the tale amusing enough to include on page 53 of his book Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974), under the heading ‘Offers victor knight odds’, but it is not true.

Marshall and Janowsky played a match at the Cercle Philidor in Paris from 24 January to 7 March 1905, and the final score was +8 –5 =4 in Marshall’s favour. The view that Janowsky suffered many unlucky accidents and that the two masters were of more or less equal strength was expressed by, for example, Alapin on pages 88-89 of La Stratégie, 17 March 1905, and page 89 also featured a letter which Janowsky wrote to Marshall on the same day as the last match game was played:

‘J’estime que le résultat de notre match est loin d’établir nos forces respectives, au contraire, étant donné que dans la majorité des parties j’ai laissé échapper soit le gain, soit la nullité, je suis persuadé que normalement j’aurais dû vaincre facilement.

J’ai donc l’honneur de vous provoquer pour un match de revanche aux conditions suivantes:

Le vainqueur sera le premier gagnant 10 parties les nulles ne comptant pas; je vous offre l’avantage de 4 parties, c’est-à-dire que mes quatre premières parties gagnées ne compteront pas; l’enjeu ne devra pas être supérieur à 5000 francs.’

An English version appeared on page 27 of the American Chess Bulletin, February 1905. The Bulletin commented that ‘such an address to a successful adversary cannot but make an unpleasant impression with the rank and file of lovers of chess and good sportsmanship’. That is hard to dispute, but it should be noted that there was no question of Janowsky offering Marshall knight odds; he was proposing to his victor the advantage of four points.

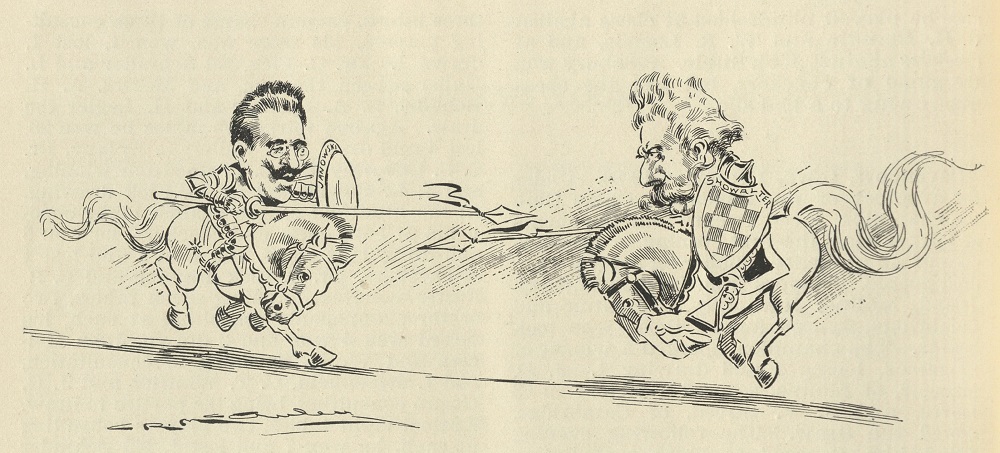

The sketch of Janowsky given below was on page 251 of the July 1905 issue of the Bulletin:

Another (less good) English version of Janowsky’s letter appeared on page 79 of Frank Marshall, United States Chess Champion by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 1994), after which Soltis commented: ‘To this Marshall made no formal reply’. That is not true either. As recorded on page 150 of La Stratégie, 19 May 1905, a reply from Marshall, written in London on 22 April 1905, was published by Janowsky in Le Monde Illustré of 29 April 1905:

‘J’accepte le défi de votre lettre du 7 mars dernier à condition que vous pourrez obtenir pour moi les mêmes arrangements que le Cercle Philidor m’a accordés pour notre précédent match.’

Despite Marshall’s acceptance, the arrangements foundered, and it was not until January-February 1908 that the return match took place (five games up, with no odds) at the villa of L. Nardus in Suresnes. Janowsky won +5 –2 =3.

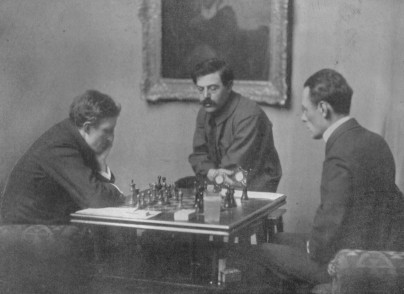

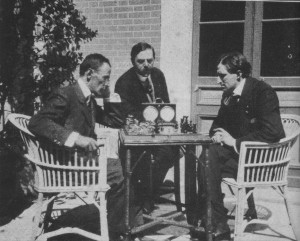

The photograph below, of Marshall, Nardus and Janowsky, is the frontispiece in The Match and The Return Match: Janowsky v. Marshall by L. Hoffer (London, 1908):

(3699)

On the basis of Janowsky’s weekly chess column in Le Monde Illustré (11 February to 18 March 1905), as well as La Stratégie of 20 February and 17 March 1905, we list the total times taken by Marshall and Janowsky in their 17-game match in Paris. Marshall, who won +8 –5 =4, had White in the odd-numbered games:

1: 4.14 – 4.11;

2: 2.30 – 2.30;

3: 2.48 – 2.13;

4: 3.48 – 4.12;

5: 3.00 – 2.48;

6: 3.19 – 3.00;

7: 2.00 – 2.12;

8: 2.05 – 1.57;

9: 4.24 – 4.21;

10: 4.14 – 4.31;

11: 3.43 – 3.46;

12: 3.10 – 2.40;

13: 4.12 – 4.40;

14: 3.20 – 2.18;

15: 2.52 – 4.57 (Le Monde Illustré) or 4.37 (La Stratégie);

16: 1.49 – 3.00;

17: 3.03 – 4.35 (times omitted by Le Monde Illustré).

(6129)

Dawid Janowsky

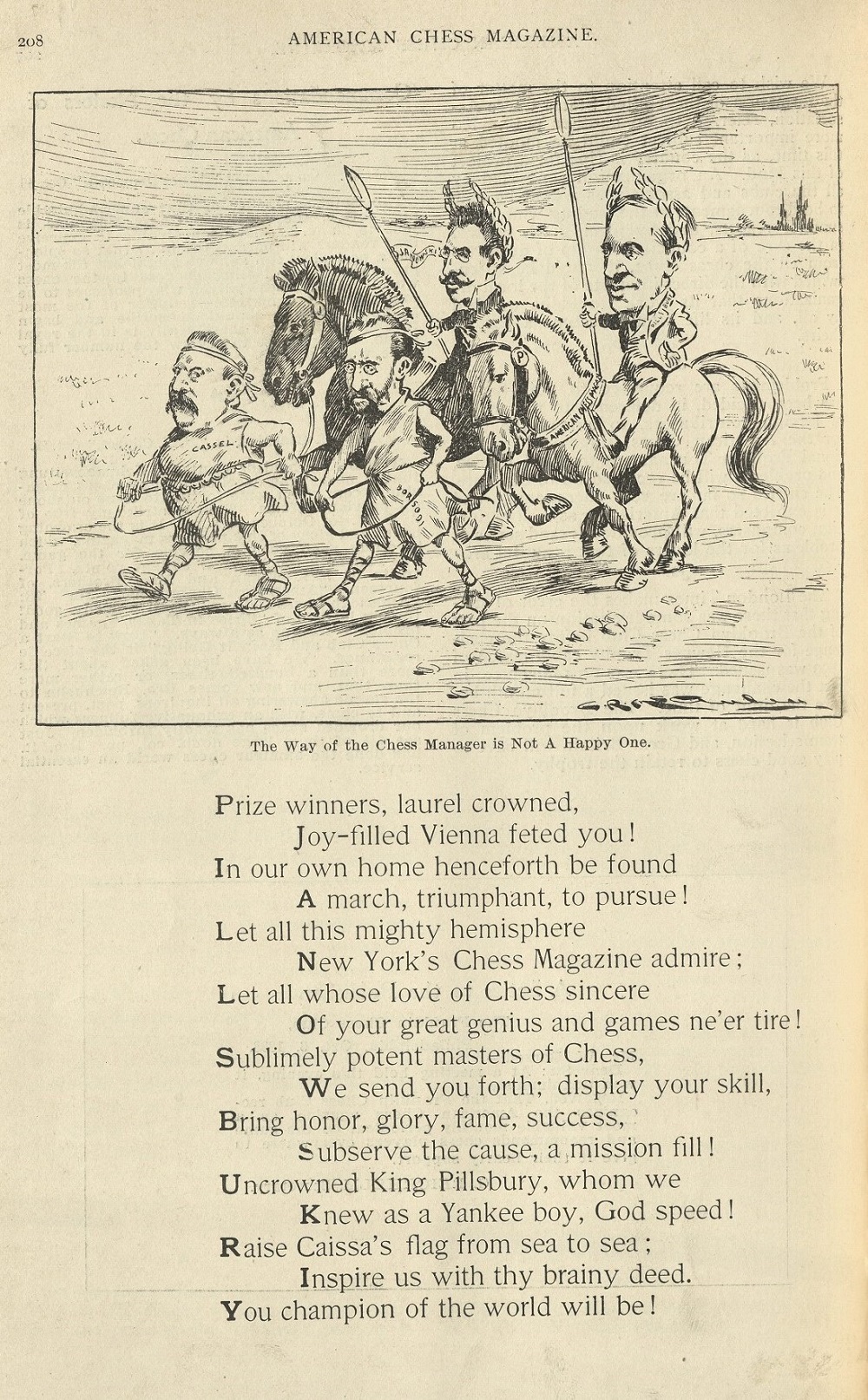

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) provides eight sketches published in the Pall Mall Gazette, 14 July 1899:

(5729)

Our feature article on the event, London, 1899 Pen-portraits, has, in addition to a group photograph, a translation of an article by ‘André de M.’ from pages 210-213 of La Stratégie, 15 July 1899. The first two paragraphs:

‘It would, I think, be difficult to imagine two men more completely dissimilar than Lasker and Janowsky. Nothing disturbs Lasker; his shirt, his clothes are the least of his worries. He is hungry; he goes to the sideboard and returns with a bread roll, which he eats with gusto while continuing his game. His legs are in his way; he puts them over one of the arms of his chair and continues to play, smoking strong cigars; when he reflects deeply he blows the smoke through his moustache with a characteristic grimace.

Janowsky, by contrast, is correctness personified. Seated before his board, he remains almost totally immobile. With a dazzling shirt, Turkish cigarettes, ice-cold lemon-squash, which he sucks through a straw, he is a refined, sensitive player par excellence, a sybaritic player who may lose merely because of a rose-leaf being crumpled.’

A great player of the olden days is the subject of a large new monograph, Vabanque Dawid Janowsky 1868-1927 by Daniel Ackermann (Ludwigshafen, 2005). In the present brief notice, a few facts and figures are provided. It is a handsome 723-page hardback in German which includes a biographical narrative, 335 games (virtually all of them annotated), tournament tables and match charts, 12 pages of endnotes (the second of which errs by attributing to us a comment in C.N. 418 by W.H. Cozens), indexes and a nine-page bibliography.

(3897)

From Cuttings:

An article entitled ‘Self publishing’ by Justin Horton dated 23 August 2013 shows that in dozens of Spectator chess columns Raymond Keene has advertised the books of Hardinge Simpole without declaring his status as a director of the company.

One extract that caught our eye was the Spectator column of 24 September 2005, which plugged a new book, David Janowski Artist of the Chess Board by Alexander Cherniaev and Alexander Meynell. The extract began:

‘Although a slim tome exists in Russian, and a massive one in German, Janowski has not been rewarded in English-language chess literature with the accolades he deserves.’

The Cherniaev/Meynell book may be regarded as an insult rather than an accolade (even the Foreword begins with an historical blunder), but a brief statistical comparison with the ‘slim tome’ in Russian, published in 1987, will suffice here:

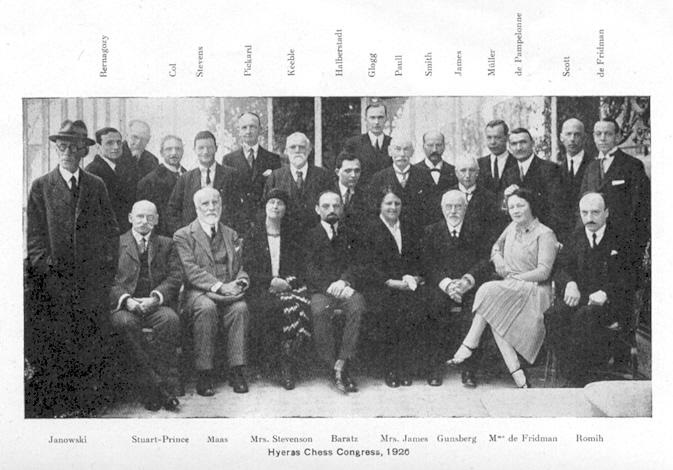

A group photograph of Hyères, 1927 was shown in C.N. 3606, and below is a picture taken at the previous year’s tournament, our source being The Book of the Second Annual Chess Congress Hyères, 1926:

(4023)

Capablanca’s victory as White against Janowsky at New York, 1918 (1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6 4 Bg5 Nbd7 5 e3 c6 6 Nbd2 Be7 7 Bd3 dxc4 8 Nxc4 O-O 9 O-O c5 10 Rc1 b6 11 Qe2 Bb7 12 Rfd1 Nd5 13 Nd6 Bc6 14 Ne4 f5 15 Bxe7 Qxe7 16 Ned2 e5 17 dxe5 Nxe5 18 Nxe5 Qxe5 19 Nf3 Qe7 20 Nd4 cxd4 21 Rxc6 Nb4 22 Bc4+ Kh8 23 Re6 d3 24 Rxd3 Qc5 25 Rd4 b5 26 Bxb5 Nxa2 27 Bc4 Nb4 28 Qh5 g6 29 Rxg6 Rad8 30 Rg7 Resigns) was annotated by the Cuban in My Chess Career, and the conclusion was discussed by Bruce Hayden on page 298 of the October 1951 Chess Review. A slightly different version of Hayden’s text appeared on pages 21-23 of his book Cabbage Heads and Chess Kings (London, 1960), as quoted below:

‘I myself kibitzed a Capablanca game, but by mail, and with interesting results. In the great New York tournament of 1918 one of Capa’s masterpieces was his game against Janowsky in the sixth round ...

Capa now played the neat combination 30 Rg7! and Black resigned; for after the forced move of 30...Kxg7 there follows 31 Qg5+ Kh8 32 Rxd8, and Black must lose his knight (32...Nd5) to prevent the two mating threats of Qf6 and also Qg8+.

Many years after, I played over the game as a youngster from My Chess Career, in which Capablanca gives it high praise and adds that “only the expert can fully enjoy it”. It was awarded Second Brilliancy Prize, but I spotted another brilliancy which, I thought, might have obtained the first prize.

The initial move is 30 Qg5. The proffered rook cannot be captured because of mate on the move, and the threat is 31 Rg8+ Rxg8 32 Qf6+ Rg7 33 Rxd8+ and mate on the next move.

The defence of 30...Qxc4 fails against 31 Qf6+ Rxf6 32 Rxd8+, forcing mate; and 30...Nd5 31 Rg7 is sufficient.

When I showed this line to masters and other experts they all gave the defence 30...Qc7. But now the brilliancy really ticks: 31 Rg8+ Rxg8 32 Qf6+ Qg7 33 Rxd8!! and mate is forced again.

So I sat me down and posted off the question. This time I received a reply. You can’t post looks of surprise and disapproval through the mail.

“I have been too busy to examine the variations which you mention”, replied the (by now) ex-world champion, “but doubtless your suggestions are correct.”

It was Brian Harley who in turn kibitzed me by correspondence. His move arrived on a postcard: 30...Rd5!!

Now it appears that all White’s efforts come to naught. Try 31 Rg8+ Rxg8 32 Qf6+ Rg7 33 Qd8+! Rg8! (Black won’t oblige with 33...Rxd8 34 Rxd8+) 34 Qf6+ with a draw by perpetual check.

Whew! What a diabolical move is that rook obstruction on d5. But then what else can one expect from a famous problem composer?

This seems to be Black’s defence all right, but later Joseph Limarzi, of the Italian Embassy in Washington, DC, took a hand at kibitz by mail. His move takes advantage of the black rook on d5, thus, after 30 Qg5 Rd5

31 Qh6.

This threat of immediate mate now not only counters the defence of ...Qe7 because of the loss of the rook on d5 but also sidetracks neatly any ideas of Black’s for a later sacrifice ...Qxc4.

Against the two defences (a) 31...Rg8 and (b) 31...Rf7 Mr Limarzi’s analysis runs: (a) 32 Rxg8+ Kxg8 33 Qe6+, winning a piece after the black king moves, by 34 Rxd5, for if 34...Qxc4 the black queen is lost by discovery after the rook checks. (b) 32 Rxd5 Nxd5 (not 32...Qxc4 33 Rd8+) 33 Rd6 (attacking the knight and threatening also 34 Rd8+), 33...Nf6 34 Rd8+ Ng8

35 Qf6+! and forces mate prettily.

Nevertheless, though all this is interesting analysis Capa was correct to clinch the win simply with the lucid elegance for which he was famous.’

In Cabbage Heads and Chess Kings Hayden did not mention an editorial interpolation in his Chess Review article: the suggestion of 30...Rd5 31 h3.

Capablanca also annotated the game, briefly, on page 20 of the New York, 1918 tournament book, as follows:

6 Nbd2: ‘d2 seems to be the better post for the queen’s knight and an improvement over the old method of proceeding against this system of defense.’

10 Rc1: ‘Here 10 Nce5 might help to hinder the development of the queen’s bishop.’

13 Nd6: ‘The object of this move is to force the bishop to c6, where it is not well placed.’

14...f5: ‘This is a two-edged sword. If he cannot soon play ...f4 or ...e5, a weakness is created which may prove fatal.’

16...e5: ‘Apparently very strong, but really leads to the loss of the game.’

19...Qe7: ‘Against any other move White would continue with 20 Bc4.’

20 Nd4: ‘The maneuvering of this knight has been really extraordinary, this being his seventh move, and it is now clear he has accomplished quite a bit.’

26 Bxb5: ‘Attacks by 26 Qh5 or 26 Rh4 are inferior to the text move.’

28...g6: ‘White threatened 29 Rh4.’

29 Rxg6: ‘A seemingly possible brilliancy beginning with 29 Rd7 is spoiled, after 29...gxh5 30 Rh6, by 30...Rf7, etc.’

In My Chess Career Capablanca wrote:

‘This game is remarkable because it would be hard to say which move lost the game, though it is probably ...f5 or ...e5, and most likely the former.’

It may be considered strange that in neither My Chess Career nor the tournament book did Capablanca criticize 7...dxc4, although innumerable other contemporary sources also passed over that move in silence.

In the quotations above from Hayden and Capablanca the moves have been converted to the algebraic notation.

(4477)

The Christmas 1969 issue of CHESS had a quiz which claimed (on pages 116 and 125) that D. Janowsky ‘was so annoyed at reaching a losing position against Sir George Thomas’ that he ‘did not arrive for resumption of play, and the tournament director upon opening the envelope merely found the word “abandonnent”.’ No occasion was specified or source given, but it seems that Janowsky’s only loss to Sir George Thomas was at Marienbad, 1925 – an 88-move game given on pages 96-97 of the tournament book.

In an article entitled ‘Unconventional Surrender’ on page 55 of the February 1950 Chess Review Hans Kmoch and Fred Reinfeld stated that such an incident occurred in the game between Müller and Yates at Kecskemét, 1927, and that White sealed ‘aufgegeben’. See page 130 of Reinfeld’s The Treasury of Chess Lore (New York, 1951). Kmoch was a participant in the tournament.

(4942)

A passage on page 49 of The Delights of Chess by Assiac (London, 1960) has come to our attention:

The two masters played each other twice in a 1926 tournament in Ghent, but both games were drawn.

(5287)

A group photograph from page 173 of the December 1925 American Chess Bulletin:

(4992)

Can any reader supply a better version of this illustration of Janowsky and Chigorin in play at St Petersburg, 1900?

It appeared opposite page 129 of M. Yudovich’s monograph Михаил Чигорин (Moscow, 1985). Two games between Janowsky and Chigorin played in St Petersburg in December 1900 were published in the 15 January 1901 issue of La Stratégie (pages 4-5 and 9-10). Chigorin won both, and the conclusion of the latter game was given in C.N. 2499 (see below, as well as pages 47-48 of A Chess Omnibus).

(5501)

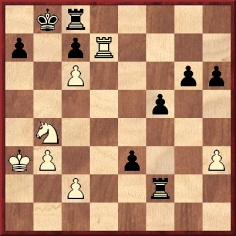

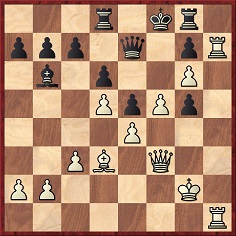

In this position how should White, to move, pursue the attack?

D. Janowsky-M. Chigorin, St Petersburg, 21 December 1900

White played 36 Rg6, and lost as follows: 36…Re7 37 Bxh6 Re1+ 38 Kd2 Nf4+ 39 Kxe1 Re8+ 40 Kf1 Qd3+ 41 Kg1 Nxh5 42 Bxg7+ Kg8 43 Bxf6+ Kf7 44 White resigns.

Instead, he could have won by inverting his 36th and 37th moves, i.e. 36 Bxh6 gxh6 37 Rg6 Rh7 38 Rxh6, etc.

Source: La Stratégie, 15 January 1901, pages 9-10.

(2499)

(6013)

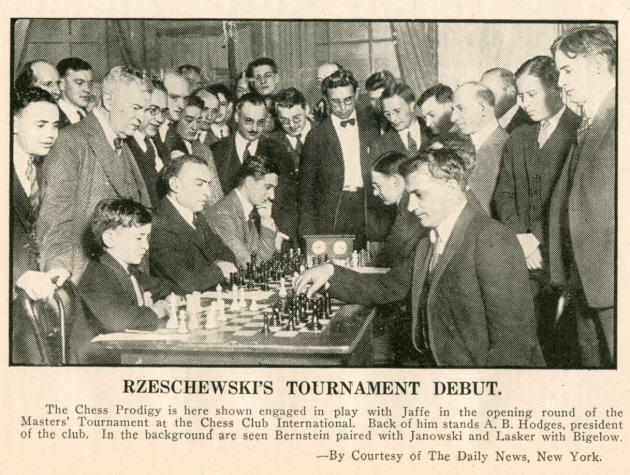

The article by Irving Chernev on the inside front cover of the April 1954 Chess Review (C.N. 6077) included 15 alleged quotes, none with sources. One was: ‘That boy understands as much of chess as I do of rope dancing.’ Page 125 mentioned that the speaker was ‘Janowsky, referring to his game with the prodigy Reshevsky’. The complete feature was reproduced on page 271 of Chernev’s The Chess Companion (New York, 1968).

On page 243 of Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters by Edward Lasker (New York, 1951) it was reported that Janowsky had made the remark to Lasker after 12 moves of the game Janowsky v Reshevsky, New York, 1922. It was a famous victory for the ten-year-old prodigy, and the following appeared on page 18 of Reshevsky on Chess (New York, 1948):

‘I was so excited and happy that I rushed home in a taxi to tell my father and mother. I couldn’t even sit down in the taxi. I jumped up and down all the way. When I got to the hotel, I ran up the stairs to our rooms, without waiting for the elevator, and broke the news to my parents: I had won from Janowsky! And then I sang. I sang so loudly that nobody could talk. It was one of the happiest days of my life.’

In Edward Lasker’s version (pages 247-248 of Chess Secrets) the prodigy’s father was in the taxi. The report on page 28 of the Sports Section of the New York Times, 13 October 1922 stated:

‘After 65 moves had been recorded, Janowsky, seeing his pawns falling one by one, resigned and was the first to offer his congratulations to the boy.’

This photograph was given on page 158 of the November 1922 American Chess Bulletin:

The tournament received a brief mention on pages 193-194 of A History of Chess by H. Golombek (London, 1976). Reshevsky’s final score and his placing were incorrect, as were Bigelow’s. Jacob Bernstein was misidentified as ‘S. Bernstein’, and the index reference to Jaffe gave his forename as Oscar, instead of Charles.

(6083)

See too C.N. 7236.

From page 73 of The English Chess Explosion by M. Chandler and R. Keene (London, 1981):

‘No-one remembers Reshevsky’s losses as an 11-year-old, but everyone knows it was at this age he beat the former World Championship Candidate, Janowski.’

Everyone knows no such thing, for the simple reason that it is untrue. Reshevsky was ten, as the book itself had stated earlier (page 35):

‘Short’s achievement was even more momentous than Capablanca’s match win against Corzo in Havana in 1900 when Capa was 12, and almost on a par with the game won by 10 year old Reshevsky against the veteran GM Janowsky in 1922.’

However, that reference is wrong on other matters. The match took place in 1901, not 1900, and Capa’s age should read 13, not 12. Note too the slapdash inconsistency: two different spellings, Janowski/Janowsky.

(1040)

The following photograph of Janowsky appeared in Le Monde Illustré on 27 September 1902, page 312:

(6137)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan comes this sketch on page 438 of the November [sic – it was mistakenly headed ‘October’] 1905 BCM:

(6149)

From Solitaire Chess by I.A. Horowitz (New York, 1962):

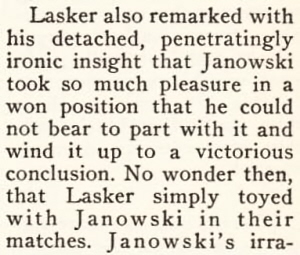

From page 17 of Why You Lose at Chess by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

Other quotes on this theme will be welcomed.

(6242)

We now add a ‘once’ account from page 72 of a book co-authored by Horowitz and Reinfeld, How To Improve Your Chess (Kingswood, 1955):

(6567)

Below is what Reinfeld wrote in ‘Emanuel Lasker: An Appreciation’ in his edition of Lasker’s Manual of Chess (Philadelphia, 1947):

(8233)

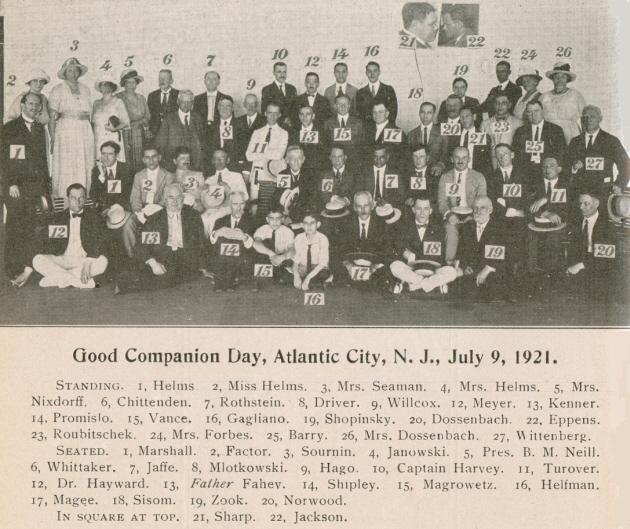

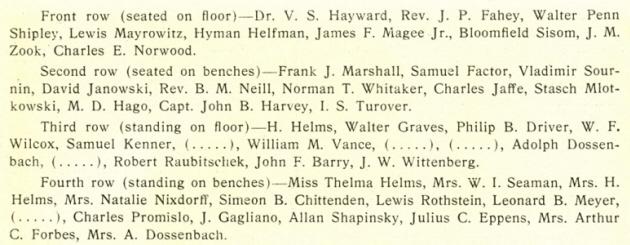

Potted biographies of Dawid Janowsky seldom mention his victory in the Eighth American Chess Congress at Atlantic City, NJ in 1921, ahead of Norman Whitaker and Charles Jaffe, with Frank Marshall finishing equal fifth. A photograph was published on page 214 of “Our Folder” (the publication of the Good Companion Chess Problem Club), August 1921:

The same picture, without the numerical references, appeared on page 128 of the July-August 1921 American Chess Bulletin, with this key on the next page:

Larger version of the photograph

(6458)

From an article ‘Tall Tales of Teetotalers’ by H. Kmoch and F. Reinfeld on pages 136-137 of the May 1952 Chess Review:

‘He considered himself the strongest player of all time ...’

What are the grounds for asserting that such was Janowsky’s belief?

(6499)

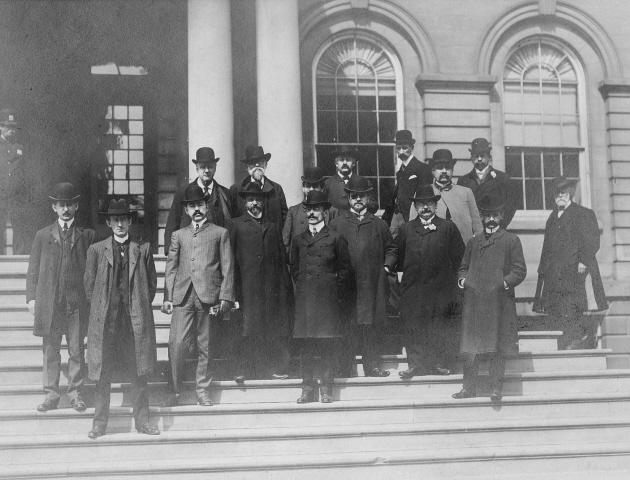

We offered a book prize for the best attempt by a reader to identify the above figures in a photograph forwarded by David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA). It was a difficult task, even though some masters, such as Marshall, Janowsky, Teichmann and Schlechter, are immediately recognizable and even though, as will be seen, the photograph concerns a famous tournament.

The winner of our contest is Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France), and we can do no better than paraphrase his excellent entry, which identifies virtually the entire group.

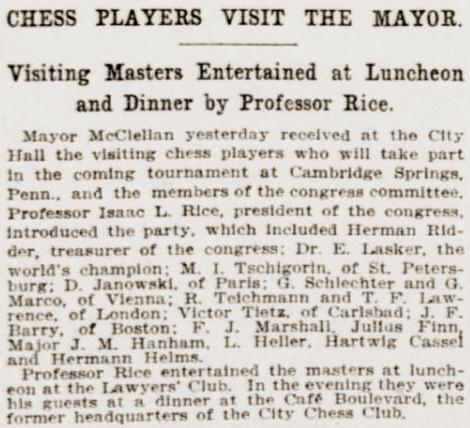

The photograph shows players in, and organizers of, Cambridge Springs, 1904. Newspaper reports of the time mentioned by Mr Thimognier relate that eight players (Lasker, Chigorin, Teichmann, Janowsky, Schlechter, Marco, Lawrence and Marshall), accompanied by the treasurer of the Carlsbad Club, Victor Tietz, arrived in the United States on the Pretoria. (Mieses followed a few days later on the Graf Waldersee.) This account of their reception appeared on page 16 of the New York Daily Tribune, 19 April 1904:

Mr Thimognier also points out that an Internet search confirms that the building in the photograph is the New York City Hall. He offers the following key:

Foreground (left to right): J. Finn, F.J. Marshall, J.F. Barry, M. Chigorin, D. Janowsky, R. Teichmann, V. Tietz, C. Schlechter and J.M. Hanham.

Background (left to right): H. Ridder, I.L. Rice, Em. Lasker, H. Cassel, T.F. Lawrence, G. Marco and N.N. (L. Heller?).

(6891)

C.N. 6683 referred to the Pearl of Zandvoort, but a less familiar term occurs on page 61 of One Move and You’re Dead by Erwin Brecher and Leonard Barden (London, 2007). The conclusion of Janowsky v Schlechter, London, 1899 is given, with the comment that White ‘forced checkmate with such an impressive move that they called it The pearl of St Stephen’s after the London hall where the tournament was played’.

Wanted: other sightings of the term.

The game ended 34 Qxh7+ Kxh7 35 Rh5+ Kg8 36 Ng6 Resigns.

(7059)

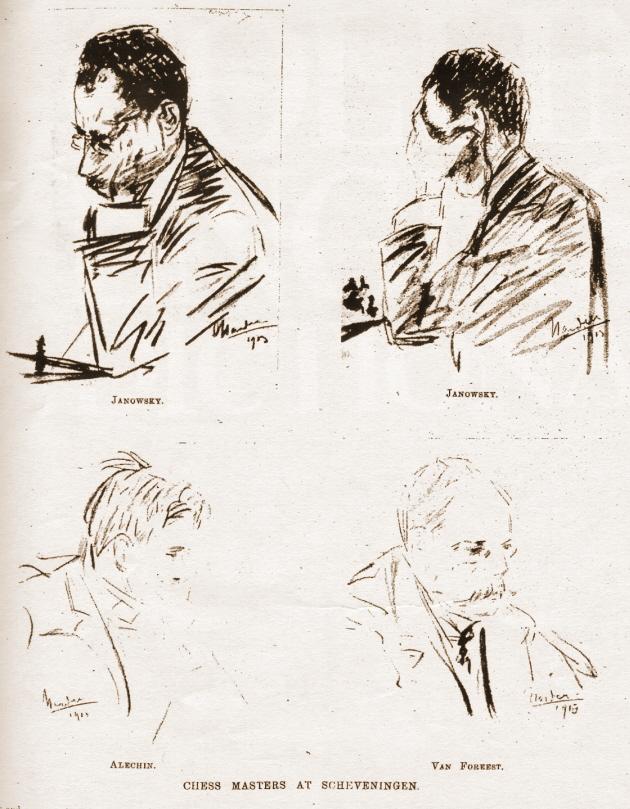

Four sketches by L. Nardus at Scheveningen, 1913 were published on page 311 of The Field, 9 August 1913:

(7145)

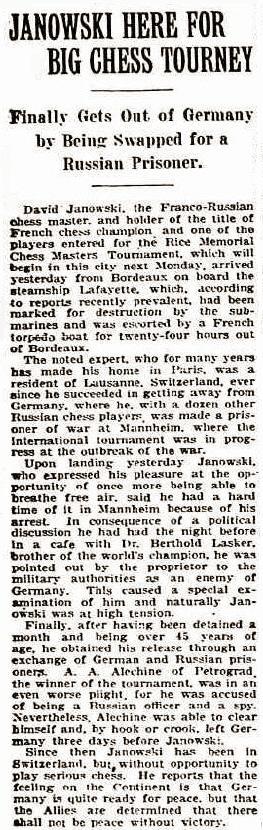

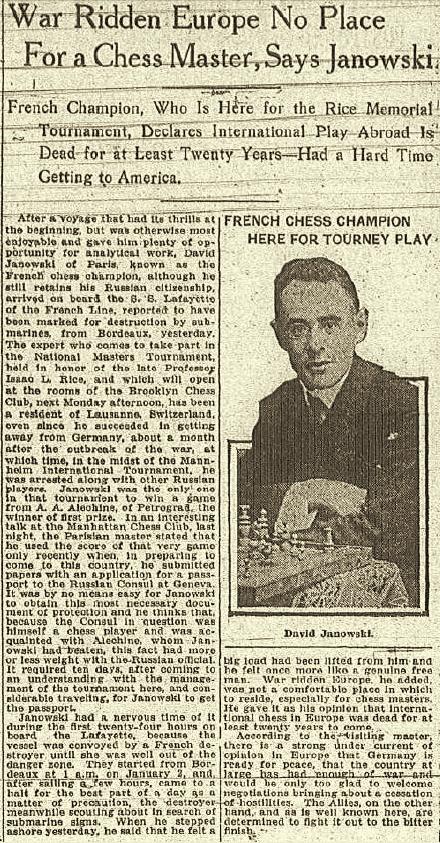

Two reports from US newspapers in January 1916 concerning Janowsky’s internment after the Mannheim, 1914 tournament, and his subsequent movements before arriving in New York at the beginning of 1916.

The Sun (New York), 12 January 1916, page 8

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 12 January 1916, page 2

(7201)

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 c5 3 c4 dxc4 4 e3 e6 5 Bxc4 Nf6 6 O-O Nc6 7 Nc3 Be7 8 Qe2 O-O 9 dxc5 Bxc5 10 a3 Bd7 11 b4 Be7 12 Bb2 Rc8 13 Rfd1 Qb6 14 Rac1 Rfd8 15 Na4 Qc7 16 b5 Na5 17 Bxe6 Bxe6 18 Rxc7 Rxd1+ 19 Qxd1 Rxc7

Noting that databases have these moves as a game in the 1912 Marshall v Janowsky match, Pierre Bourget (Quebec, Canada) asks whether the game really ended at move 19 (as a win for White).

The answer is no. The above is less than half of the game, as Janowsky did not resign until move 45. The full score (eighth match-game, Biarritz, 12 September 1912) is on pages 440-441 of La Stratégie, November 1912, the additional moves being: 20 b6 axb6 21 Nxb6 Rc6 22 Na4 Nc4 23 Bxf6 gxf6 24 Nd4 Rc7 25 h4 Bd7 26 Qf3 Ne5 27 Qd1 Bxa3 28 Nc2 Bf8 29 Nb6 Bg4 30 f3 Be6 31 Nd4 h5 32 Nxe6 fxe6 33 Qd8 Rc1+ 34 Kf2 Kf7 35 Nd7 Be7 36 Nxe5+ fxe5 37 Qh8 Bxh4+ 38 Ke2 Bg3 39 Qxh5+ Kf6 40 Qh3 Be1 41 Qh6+ Kf7 42 g4 Bb4 43 g5 Be7 44 g6+ Ke8 45 Qh8+ Resigns.

(7455)

An odd suggestion about Dawid Janowsky by I.A. Horowitz on page 8 of Solitaire Chess (New York, 1962):

‘Parodying one of Harry Lauder’s songs, the Polish master averred: “I’d rather lose my queen than lose my bishop.”’

(8317)

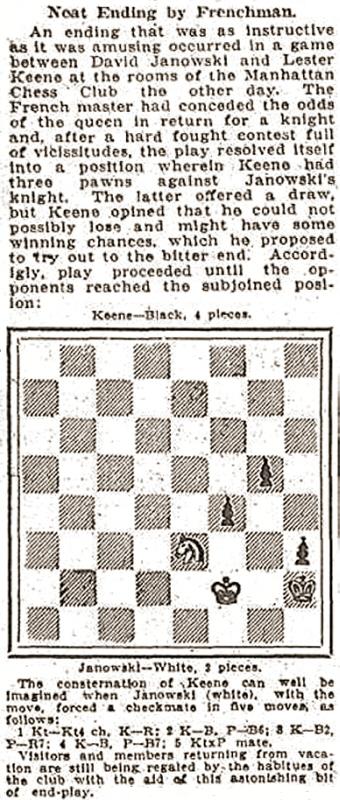

From Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) comes this item on page 12 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 26 July 1917:

The position was given in C.N. 1108 and, when reproduced on pages 10-11 of Chess Explorations, caused Hans Ree to go off the rails on page 81 of the 8/1996 New in Chess.

The source specified in C.N. 1108 was page 313 of the October 1917 BCM, which took the position from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The newspaper’s text was also given on page 240 of the November 1917 American Chess Bulletin. See too page 7 of La Stratégie, January 1918. Furthermore, the position was discussed extensively on pages 38-39 of Jeugdschaak by L.G. Eggink and M. Euwe (Lochem, 1950), although White was named as Frank Marshall, and the position was said to have occurred at the Manhattan Chess Club in 1907.

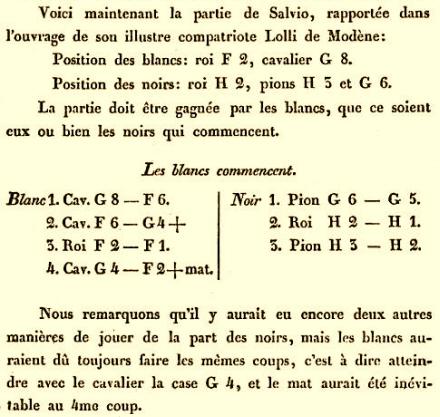

In the domain of chess compositions the manoeuvre leading to mate by a knight on f2 has been known centuries. Below, for instance, is an extract from page 8 of Découvertes sur le cavalier (aux échecs) by C.F. Jaenisch (St Petersburg, 1837):

About Lester Keene a comment by William Lombardy on page 268 of the May 1976 Chess Life & Review is added warily:

‘Long ago there was a player at the Manhattan Chess Club, Lester Keene by name, who customarily defended the mate threatened at KR7 simply by playing ...P-KR3!’

(8516)

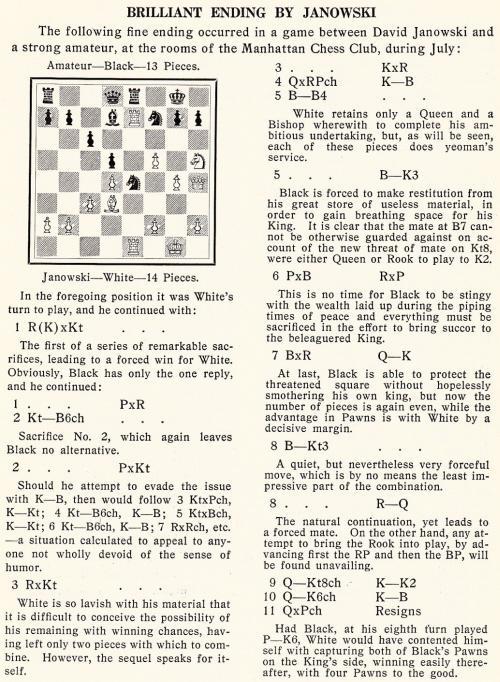

The other Janowsky position given in C.N. 1108, and on page 11 of Chess Explorations, was the conclusion of a game also played at the Manhattan Chess Club in July 1917. Below is its appearance on page 147 of the July-August 1917 American Chess Bulletin:

The full game has still not been found.

(8517)

Continuing with the ‘once’ theme, we give a snippet from page 324 of Pump Up Your Rating by Axel Smith (Glasgow, 2013), a highly interesting book:

In the bas quartiers of the Internet this Janowsky quote appears regularly and sourcelessly. As mentioned on page 396 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, it comes from Capablanca’s Lectures book:

This adds the worthwhile information that Janowsky often expressed such a view about the endgame, and that Capablanca strongly disagreed with it.

(8693)

Janowsky’s ‘I detest the endgame’ comment, recollected by Capablanca, was also quoted on page 396 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.

From page 73 of Championship Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1938):

Who?

According to a reference book’s entry on him, this chessplayer attacked wildly, was unaware when to attack, was neither a scientist nor a theoretician, did not know, or was unable to explain, why what he did at the chessboard had to be done, cared relatively little about the outcome of a game, underestimated his opponents, appeared incapable of learning from his errors, was excessively self-confident, frequently lost his temper and was intolerable when defeated, did not have many friends and was virtually forgotten when he died.

(9573)

The effusion of criticism and ridicule referred to in C.N. 9573 was on page 95 of B.J. Horton’s Dictionary of Modern Chess (New York, 1959):

(9582)

C.N. 9582 showed how Dawid Janowsky was derided on page 95 of B.J. Horton’s Dictionary of Modern Chess (New York, 1959). Another example, anchored in tittle-tattle, comes from pages 99-100 of The World’s Great Chess Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1951):

The famous game published by Fine was against ‘Schallop’ (sic) at Nuremberg, 1896.

Dawid Janowsky (American Chess Bulletin, February 1927, page 28)

(9655)

...

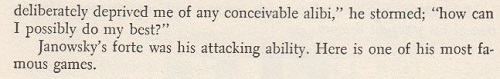

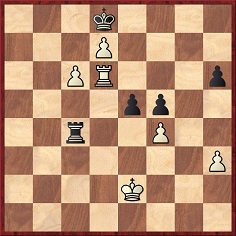

Computer searches today show that a choice of en passant captures is not rare. An old specimen between leading players is the seventh match-game Marshall v Janowsky, Paris, 9 February 1905, e.g. as published on pages 70-71 of volume two of Halpern’s Chess Symposium (New York, 1905):

Pillsbury’s notes were originally on page 2 of the Philadelphia Inquirer, 5 March 1905:

1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 cxd5 cxd5 5 Bf4 Nc6 6 e3 e6 7 Nf3 Be7 8 Bd3 Nh5 9 Be5 Nxe5 10 Nxe5 Nf6 11 O-O O-O 12 f4 g6 13 Qf3 Ne8 14 Rac1 Ng7 15 Qh3 a6 16 Qh6 Bf6 17 g4 Ne8 18 Rc2 Bg7 19 Qh3 Nd6 20 Rg2 b5 21 g5 Nc4 22 Rf3 Bb7 23 Qh4 Nxe5 24 fxe5 h5 25 Ne2 Rc8 26 Rf1 Qa5 27 Nf4 Rc7 28 Nxh5 gxh5 29 Qxh5 Rfc8 30 Rgf2

30...f5 31 exf6 Resigns.

See also En passant (Chess).

However often Janowsky may or may not have been called ‘Jan’ orally, it is difficult to find the nickname in print during his lifetime. One instance occurs in G.C. Reichhelm’s annotations to the 16th match-game between Janowsky and Marshall, Paris, 4 March 1905, as published on pages 90-91 of volume two of Halpern’s Chess Symposium (New York, 1905). The note after 43...e5 was: ‘In the vain hope that “Jan” would take at once.’

In passing, we mention a discrepancy over the game’s conclusion.

Reichhelm gave ‘48 PxP RxP (An “oversight”.) RxR wins’, whereas some sources state that Marshall resigned after White’s 48th move. Those sources include Marshall’s own brief coverage of the game on pages 36-37 of a booklet on the match (published in London in 1905 with his annotations from the Manchester Guardian). Two noteworthy publications which presented the conclusion as 48 fxe5 Rxc6 49 Rxc6 Resigns were pages 84-86 of La Stratégie, 17 March 1905 (notes by Alapin) and, as shown below, pages 106-107 of the April 1905 Deutsche Schachzeitung (notes by Tarrasch from the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger):

Tarrasch gave similar annotations in Die Moderne Schachpartie (various editions, with different page numbers).

Moreover, according to the range of contemporary publications consulted, Black’s 47th move was ...Rc4, and not ...Rc5 as indicated by one or two unreliable databases.

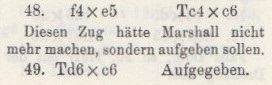

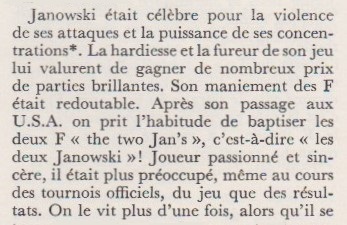

Concerning ‘the two Jans’, a number of reference works (see, for instance, the entries on Janowsky in the Dictionnaire des échecs, the hardback edition of Golombek’s Encyclopedia of Chess and the 1984 edition of The Oxford Companion to Chess) affirm that this was a common term in the United States to describe a bishop pair. An extract from page 206 of the Dictionnaire des échecs by F. Le Lionnais and E. Maget (Paris, 1967):

We have yet to trace the term in chess literature during Janowsky’s lifetime.

After presenting some victories by Janowsky [against Trenchard, Ettlinger, N.N. and Alapin] C.N. 351 commented:

... such games offer little support to the theory that Janowsky was obsessed with retention of the bishop pair. On the other hand, on page 330 of the October-November 1904 issue [of the Wiener Schachzeitung] Tarrasch, annotating the Cambridge Springs game Mieses v Janowsky remarks: ‘Janowski ist einer der wenigen Spieler, die das Geheimnis der Läufer begriffen haben und die latente Kraft dieser Figuren herauszuholen verstehen’.

(9656)

One of the games given in C.N. 351:

Dawid Janowsky – S. A.....r

Vienna, 20 October 1900

(Remove White’s knight at b1.)

1 f4 d5 2 e3 e6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 b3 Be7 5 Bb2 c5 6 Ne5 O-O 7 Bd3 Nc6 8 Qf3 Nb4 9 g4 Nxd3+ 10 cxd3 b6 11 g5 Nd7 12 Ng4 Ba6 13 Nf2 f6 14 h4 Bb7 15 Ke2 Qc7 16 g6 h6 17 Ng4 d4 18 Qh3 Bxh1 19 Nxh6+ Kh8 20 Qg4 Qc6 21 Nf7+ Kg8 22 Rxh1 Rxf7 23 Rg1 f5 24 Qh5 Nf6 25 gxf7+ Kf8 26 Qh8+ Kxf7 27 Rxg7 mate.

Source: Wiener Schachzeitung, January 1901, pages 16-17.

An endnote on page 258 of Chess Explorations:

‘S. A.....r’ may have been Sigmund Auspitzer, a member of the Wiener Schach-Club mentioned on page 41 of the February 1900 Wiener Schachzeitung.

In C.N. 2151 Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) noted that

24...Bf6 would have won for Black. See page 36 of Kings,

Commoners and Knaves.

A consultation game in which Dawid Janowsky (White) faced Frank J. Marshall shows the former’s liking for the bishop pair:

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Bc4 cxb2 5 Bxb2 Nf6 6 Nf3 d5 7 exd5 Bb4+ 8 Nc3 Qe7+ 9 Be2 Ne4 10 Rc1 O-O 11 O-O Nxc3

12 Rxc3 Bxc3 13 Bxc3 Nd7 14 Re1 Nf6 15 Bd3 Qd8 16 Re5 Re8 17 Rg5 h6 18 Rg3 Nh5 19 Bc2 Nxg3 20 hxg3 f5 21 g4 Re4

22 Ne5 Qg5 23 d6 cxd6 24 Qxd6 Qc1+ 25 Bd1 Rxe5 26 Bxe5 Kh7 27 Kh2 Be6 Drawn.

The game, played at the Automobile Club de France in Paris in October 1907, was published on pages 386-387 of La Stratégie, 20 November 1907 with Janowsky’s notes from Le Monde Illustré. Those annotations were the basis for what appeared on pages 289-290 of Voronkov and Plisetsky’s book on Janowsky (Moscow, 1987) and on pages 472-474 of Ackermann’s monograph (Ludwigshafen, 2005).

La Stratégie stated that Janowsky was partnered by Bonaparte Wyse, and Marshall by le baron de Laforie, although the annual index (page 454) gave le comte de Laforie. In the Soviet and German books the name was, respectively, Лафори and Lafore.

(9704)

Giving the game in his column on page 10 of the New York Evening Post, 7 December 1907, Emanuel Lasker put ‘Baron de la Farée’.

C.N. 2583 (see page 407 of A Chess Omnibus) quoted Najdorf on page 256 of Chess Life, November 1962:

‘When I play chess, I hardly ever calculate the play in detail. I rely very much on an intuitive sense which tells me what are the right moves to look for.’

An addition from pages 34-35 of How Not to Play Chess by E.A. Znosko-Borovsky (London, 1931):

‘Janowski, one of the most brilliant of masters, was once asked how he managed to play simultaneous games so well, making his moves, as he had to do, almost without thinking. He answered: “I play them as well as I do serious games. I see at once what move to make in a given position. In a tournament I would verify this by analysis, in a simultaneous display I do not, but I know that it is a good move.”’

In later editions the passage was on pages 41 and 46-47. The French version below is from page 32 of one of the editions of Comment il ne faut pas jouer aux échecs (Lille, 1948):

‘Le maître Janowski avouait un jour qu’il jouait ses parties simultanées aussi bien que ses parties sérieuses. “Je vois immédiatement le bon coup, disait-il. Toutefois, dans les tournois, je le vérifie par des calculs serrés, tandis que dans les simultanées je ne vérifie pas.”’

(9826)

The present item begins by drawing together a set of contradictory claims discussed in C.N.s 1160, 1322, 1667, 2592 (see page 258 of Chess Explorations and page 111 of A Chess Omnibus) and, more recently, in C.N. 10002.

C.N. 1160 commented with regard to Das Spiel der Könige by Alfred Diel (Bamberg, 1983):

Another example of how information undergoes transformations, as hacks add a bit here, take out a bit there, and turn stories inside out and upside down on no more than a whim, concerns the description of Janowsky’s play (source never given) as ‘like Marie Antoinette – beautiful but unfortunate’. Diel decides the story would be more interesting if the words were put in Janowsky’s mouth. That, and an exchange of queens, gives the following (page 118):

‘After losing a game, Dawid Janowsky complained: “Chess is like Mary Stuart – beautiful but unfortunate”.’ [‘Nach einer verlorenen Partie klagte der Meister David Janowski, “Schach ist wie Maria Stuart – schön, aber unglückselig”’.]

C.N. 1322 pointed out the following passage about Janowsky on page 21 of The World Chess Championship: Steinitz to Alekhine by Pablo Morán (London, 1986):

‘He had a very high opinion of himself as a player and once compared his play to Mary Stuart, the Queen of Scotland, as both were “splendid but unlucky”.’

Morán’s original text, from page 27 of Los campeonatos del mundo de Steinitz a Alekhine (Barcelona, 1974):

‘Se creía superior a todos y comparaba su estilo con la reina de Escocia, María Estuardo, “hermosa, pero sin suerte”.’

In C.N. 1667 Jack O’Keefe (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) noted that page 90 of the 1987 Russian book on Janowsky by S.B. Voronkov and D.G. Plisetsky quoted from Pester Lloyd, 21 June 1898:

‘According to Janowsky, his play is like Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots: “beautiful but unlucky”.’

Subsequently, we found an English version of the Pester Lloyd article in the American Chess Magazine, with the following on pages 63-64 of the August 1898 issue:

‘His play is, according to a remark of his own, like Mary Stuart, “beautiful but unfortunate”.’

C.N. 2592 cited a note by Hermann Helms on page 11 of the New York Evening Post, 22 June 1918 (in a discussion of Capablanca v Fonaroff, New York, 1918):

‘A real inspiration and, against an adversary of the Cuban’s stamp, would have made of Black’s game a genuine masterpiece, except for a slight flaw. “Beautiful, but unfortunate” about expresses it, in the language of the late W.H.K. Pollock when he was wont to draw a parallel between an unsound, brilliant combination and Mary, Queen of Scots.’

We commented that this was the only time that we recalled seeing the ‘beautiful, but unfortunate’ remark attributed to Pollock (or, indeed, to anybody other than Janowsky). Now, a comment can be added from a report about New York, 1915 on page 92 of the May-June 1915 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Neither A.B. Hodges nor E. Michelsen, who brought up the rear, came up to expectations, but ... the latter probably played the liveliest chess of any in the competition. With him it was a case of “beautiful but unfortunate”, as the late W.H.K. Pollock was wont to say.’

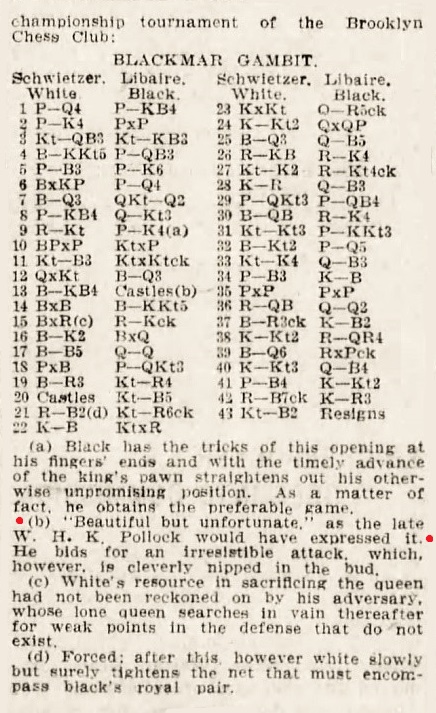

Moreover, there is an earlier instance of Hermann Helms ascribing such a remark to Pollock, is his column on page 9 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 13 May 1906, which gave a game played in Brooklyn by George Schwietzer and Edward Libaire:

1 d4 f5 2 e4 fxe4 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 c6 5 f3 e3 6 Bxe3 d5 7 Bd3 Nbd7 8 f4 Qb6 9 Rb1 e5 10 fxe5 Nxe5 11 Nf3 Nxf3+ 12 Qxf3 Bd6 13 Bf4

13...O-O 14 Bxd6 Bg4 15 Bxf8 Re8+ 16 Be2 Bxf3 17 Bc5 Qd8 18 gxf3 b6 19 Ba3 Nh5 20 O-O Nf4 21 Rf2 Nh3+ 22 Kf1 Nxf2 23 Kxf2 Qh4+ 24 Kg2 Qxd4 25 Bd3 Qf4 26 Rf1 Re5 27 Ne2 Rg5+ 28 Kh1 Qf6 29 b3 c5 30 Bc1 Re5 31 Ng3 g6 32 Bb2 d4 33 Ne4 Qc6 34 c3 Kf8 35 cxd4 cxd4 36 Rc1 Qd7 37 Ba3+ Kf7 38 Kg2 Ra5 39 Bd6 Rxa2+ 40 Kg3 Qf5 41 f4 Kg7 42 Rc7+ Kh6

43 Nf2 Resigns.

The notes were reproduced on page 164 of the August 1906 American Chess Bulletin.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 7 March 1912, page 14

C.N. 10002 mentioned our wish to add some references to Marie Antoinette’s name in connection with Janowsky (see C.N. 1160 above), but they are still proving surprisingly elusive. Any citations mentioning a third queen, Mary Tudor, would also be welcome.

Attributions to Janowsky are fertile ‘once’ territory, and an old specimen comes from page 593 of the Literary Digest, 12 November 1898:

Another example of ‘once’ is on pages 44-45 of Jewish Chess Masters on Stamps by F. Berkovich (Jefferson, 2000):

‘Janowsky himself once described his game as “like Mary Queen of Scots – beautiful but unfortunate”.’

Finally, an inevitable contribution by Andrew Soltis, from page 204 of his book Why Lasker Matters (London, 2005):

‘Janowsky himself once compared his play to Mary Queen of Scots – “beautiful but unlucky”.’

(10535)

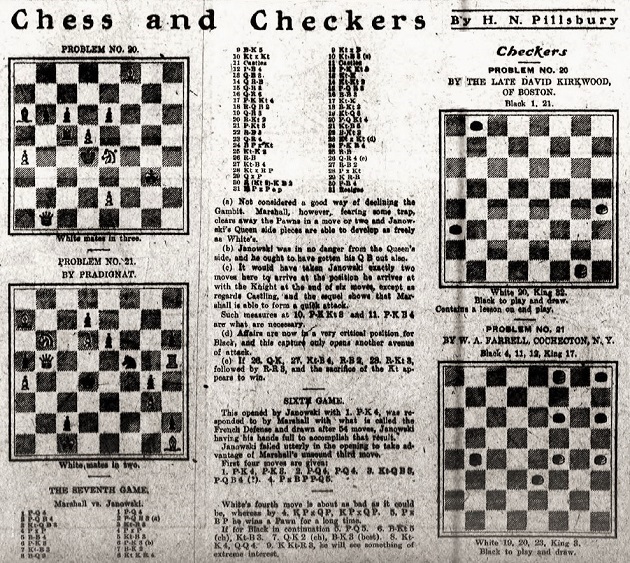

Mate in three

This composition was given in C.N.s 1428 and 1465 (see page 18 of Chess Explorations), our sources being page 74 of the American Chess Bulletin, March 1927 and page 311 of issue 10 of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français. The latter publication stated that the problem had appeared in Le Monde Illustré when Janowsky had a weekly column there, but no date was given.

We add now that it was published, without a source, on page 29 of La Stratégie, 21 January 1903 and that the previous page had another composition by the master:

Mate in two.

(10711)

Page 70 of The Big Book of World Chess Championships by A. Schulz (Alkmaar, 2016) states that Dawid Janowsky ‘died, only 56 years old, alone and completely penniless’.

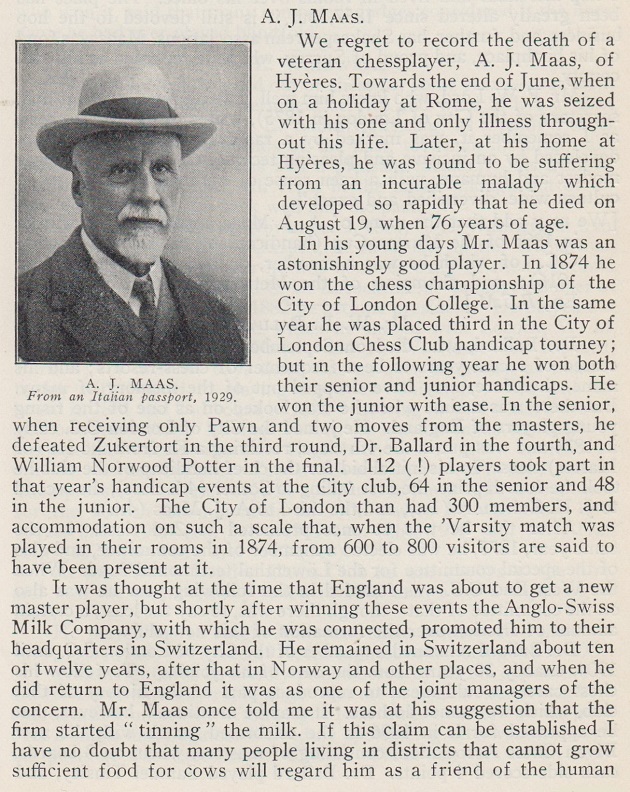

At the time of his death, aged 58, Janowsky’s circumstances were indeed dire, but the financial support of A.J. Maas is not to be forgotten. From page 553 of L’Echiquier, January 1927:

‘Le maître Janowski vient de mourir, samedi, 15 janvier, à la clinique de Hyères où, grâce à la générosité de M. A.J. Maas, le grand maître a pu être entouré de tous les soins que nécessitait une maladie incurable.’

For photographs of Maas, see C.N. 3606 and (a group picture also featuring Janowsky) C.N. 4023.

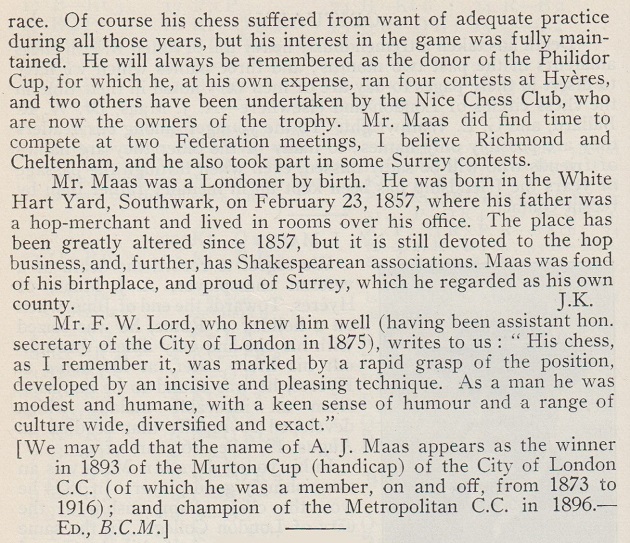

John Keeble wrote an obituary of Maas on pages 413-414 of the October 1933 BCM:

(10776)

C.N. 10776 referred to the financial support given to Dawid Janowsky, shortly before his death in Hyères, by A.J. Maas.

On page 16 of the January 1956 Chess Review Ossip Bernstein described the oscillating relationship between Janowsky and Léonardus Nardus and concluded:

‘A few weeks before Janowsky’s death in 1927 he fell very ill. I cabled Nardus, who then lived in Tunisia, and he immediately sent a substantial amount of money for Janowsky.’

(10869)

The group photograph of Budapest, 1896 is fairly well known – see, for instance, page 5 of John C. Owen’s tournament book (Yorklyn, 1994) – but a particularly good version was published on page 793 of the 22 November 1896 edition of Vasárnapi Ujság (with Marco and Maróczy’s names transposed):

(10913)

Two books by Edward Lasker quoted a conversation with Janowsky in Berlin in 1910, at the time of the latter’s world title match against Emanuel Lasker.

From page 101 of The Adventure of Chess (New York, 1950):

‘Instead of admitting that he spent his nights at roulette, he said to me one day: “I don’t think I will win a game in this match. Lasker plays too stupidly for me to look at the board with any interest.”’

From page 115 of Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters (New York, 1951):

‘After losing the first three games of the match, he said to me: “Your namesake plays such stupid chess that I simply cannot look at the board while he is thinking. I am afraid I shan’t do well in this match at all.”’

Edward Lasker’s statements on chess history require caution. For example, page 101 of The Adventure of Chess placed both of the longer Lasker v Janowsky matches in Berlin. On that point, page 88 of Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters was correct (the former ‘took place in Paris in the fall of 1909’) but wrongly asserted that it was for the world title.

(11155)

See Lasker v Janowsky, Paris, 1909.

Our article on the Lasker v Janowsky match in Paris includes the following:

The opening words of the Foreword (page 11) to the dire book David Janowski Artist of the Chess Board by Alexander Cherniaev and Alexander Meynell (Aylesbeare, 2005):

‘At the present time the career of David Janowski amounts to a gap in most people’s knowledge of chess history. They know about him because of the two world championship matches (1909 and 1910) which he played against Emanuel Lasker – and lost without a fight.’