Edward Winter

A miscellany of older items from Chess Notes, together with some of our other writings (most notably from Kingpin).

C.N. 5 mentioned that opposite page 272 of P. Feenstra Kuiper’s Hundert Jahre Schachturniere there is a photograph of Emanuel Lasker on the beach up to his head in sand (Scheveningen in 1927).

In Nicolas Giffard’s La fabuleuse histoire des champions d'échecs (Paris, 1978) Fischer appears flaked out over a bench, recovering from an arduous jog, and Petrosian sits in shorts (and in colour) reading a newspaper in a haystack.

(6)

In the Giffard work referred to in C.N. 6 the third part is entitled ‘The Reign of Lasker’; it begins with the birth of Morphy.

Giffard is full of surprises, but the absence of any index is not one of them. The diagrams are bigger than anything you have seen apart from a tournament demonstration board and lend the book an air of high vulgarity. The text is not very informative and not very accurate. Anecdotes are employed as a space-filling substitute for facts. No writer reporting them will ever care for the accuracy of either facts or anecdotes. (Are we alone in feeling that the real disease of anecdotizing is based on the unpleasant assumption that the reader will not actually care if he is being spun a yarn?)

It is not easy to take seriously a work tracing the history of chess champions which sticks colour pictures of Polugayevsky and Petrosian in between the sections allegedly dealing with Pillsbury and Schlechter. Opposite a page concerning the epic Capablanca-Alekhine match of 1927 is a full-page colour portrait of the author’s friend and preface writer Aldo Haïk, the 1972 French champion. Mistakes abound, as usual especially in the early chapters. A treasure house of misconceptions.

(212)

‘Probably the strongest player who never won anything’ is how Heidenfeld describes Philipp Hirschfeld (1840-96) in Golombek’s The Encyclopedia of Chess (London, 1977). Hirschfeld never played in a tournament and either lost or drew all of his matches. Some idea of his skill, though, is given by this defeat of Adolf Anderssen:

Philipp Hirschfeld – Adolf Anderssen

Berlin, July 1860

Evans Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Ba5 6 d4 exd4 7 O-O dxc3 8 Qb3 Qf6 9 e5 Qg6 10 Nxc3 Bxc3 11 Qxc3 Nge7 12 Ng5 Nd8 13 Be3 h6 14 Nh3 b6 15 Nf4 Qc6 16 Qb3 Ne6 17 Nxe6 fxe6 18 Rfd1 Qe4 19 Rd4 Qxe5 20 Rad1 Nf5

21 Bxe6 Nxd4 22 Bf7+ Kf8 23 Bxd4 Qf5 24 Bd5 c6 25 Qa3+ Ke8 26 Re1+ Kd8 27 Qe7+ Kc7 28 Be5+ Kb7 29 Bxc6+ Kxc6 30 Qd6+ Kb7 31 Qd5+ Ka6 32 Re4 b5 33 a4 Rb8 34 axb5+ Rxb5 35 Ra4+ Kb6 36 Qd6+ Resigns.

Just to repeat, Anderssen was Black.

Source: Adolf Anderssen by H. von Gottschall, page 190.

(3)

Michael Squires (Blackwell, England) wonders whether any of Anderssen’s victories in the encounter with Hirschfeld are extant. The standard collections give none. He also points out that Golombek’s book suggests that the ‘match’ took place in 1861, while other sources say 1860.

Granville Whatmough (Preston, England) quotes from Amenities and Background of Chess-Play by William Ewart Napier:

‘Philipp Hirschfeld, chief of the inveterately unsung, is now for the first time in our anthology fetched from that rich limbo which is the shame and byproduct of reckless hero worship. He was born about 1840, on the Baltic in Prussia. Dr Max Lange in 1859 selected this youth as co-editor of the Deutsche Schachzeitung. It was Hirschfeld’s great good fortune to gain distinction as an academician, a chess master and a magnate in commerce. He settled in London, where he became promoter and patron of the game which he had graced as a player.’

(114)

C.N. 3 (see page 28 of Chess Explorations) mentioned that in Golombek’s Encyclopedia Wolfgang Heidenfeld described Hirschfeld as ‘probably the strongest player who never won anything’. A discussion of the matter on pages 86-87 of the new Renette/Zavatarelli book (C.N. 10940) concludes that Heidenfeld’s suggestion is ‘likely refuted’.

(10944)

An endnote on page 257 of Chess Explorations in relation to C.N. 114:

Although there were games between Anderssen and Hirschfeld in the 1861 Deutsche Schachzeitung, they were dated 1860.

‘Briefly, in an endgame the solver is fighting against material odds; in a problem he is fighting against time.’ (D.J. Morgan, BCM, June 1963, page 182).

George Jelliss (Rugby, England) points out that the first paragraph of Chapter 1 of The Enjoyment of Chess Problems by Kenneth S. Howard (first edition Bell, 1943 and fourth edition Dover, 1967) ends with the sentence, ‘In an endgame the solver is fighting against material odds; in a problem he is fighting against time.

Mr Jelliss comments:

‘I doubt if this is the earliest occurrence of the saying. I also doubt if it is true. The threat of mate in either type of composition will always wonderfully concentrate the mind of the beleaguered party to respond decisively.’

(79 & 390)

Who was the strongest player ever to finish a tournament with no points? Our nomination is Tjeerd van Scheltinga, who scored a duck at Amsterdam, 1936. (1-2 Euwe, Fine 5 points; 3 Alekhine, 4½ points; 4-6 van den Bosch, Grünfeld, Landau 3½ points; 7 Kmoch 3 points; 8 van Scheltinga 0 points. In fairness to the Dutchman it must be said that the seven losses were all hard-fought. Alekhine, for example, required 79 moves to win.

(219)

Has any reader come to grips with the Russian language by means of A Chessplayer’s Guide to Russian by Hanon W. Russell (privately printed, 1972)? We were put off by Black’s P-QR3 being translated as algebraic ...a3 on page 3, to say nothing of the very first sentence: ‘A noun is a word that describes a person, place or thing.’ Sounds more like an adjective to us.

(230)

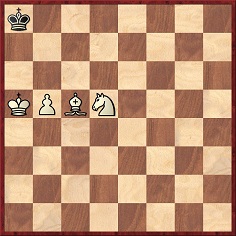

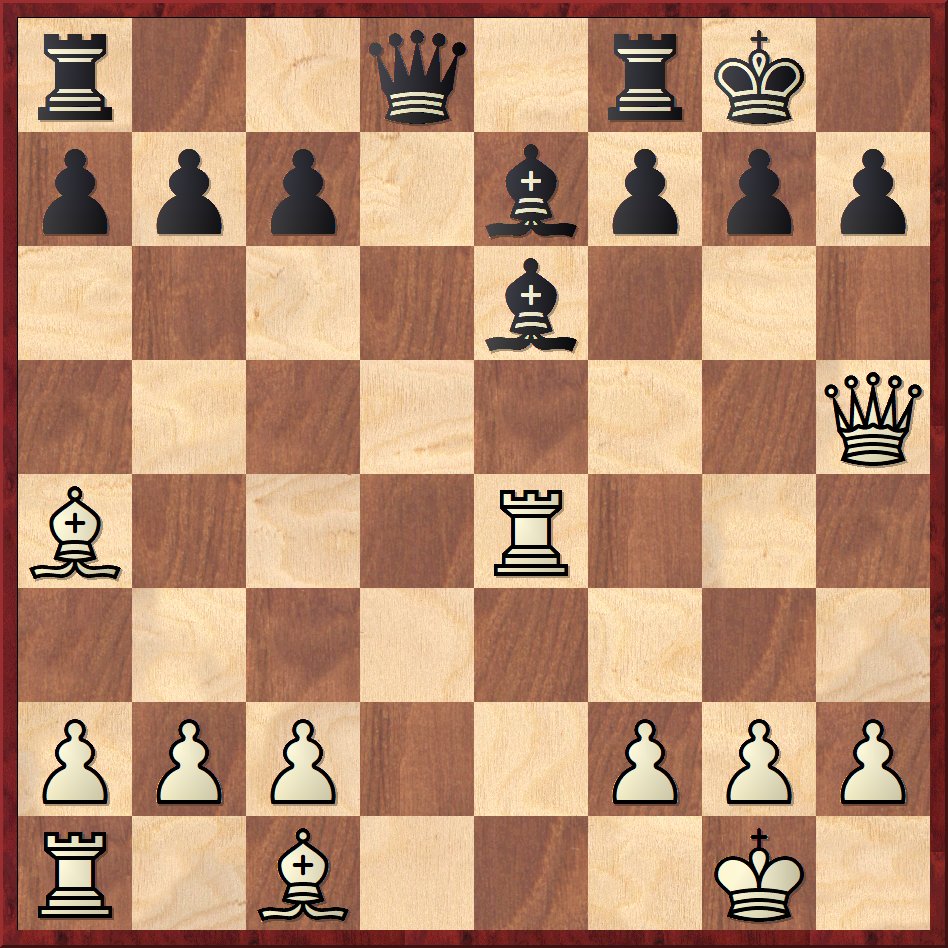

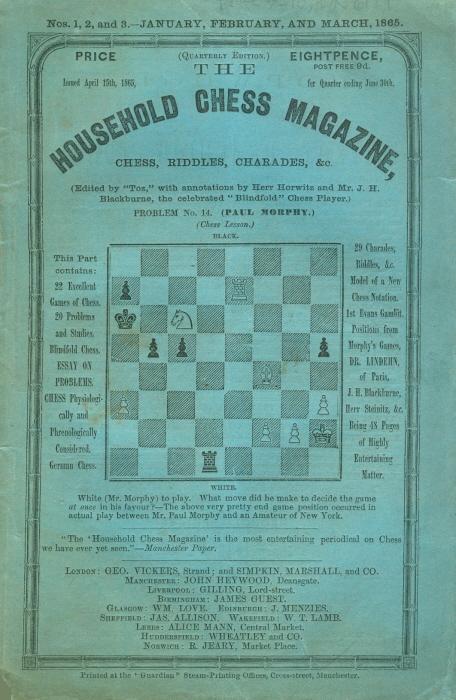

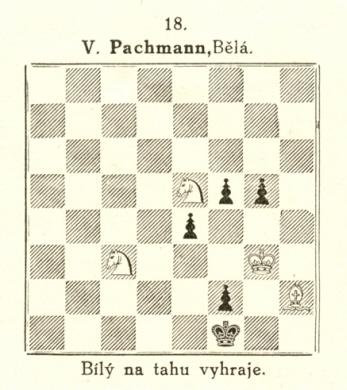

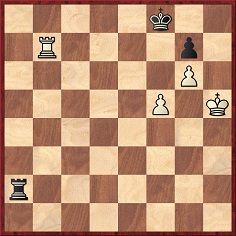

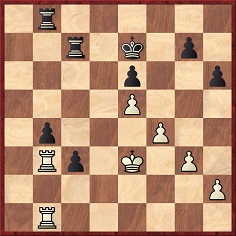

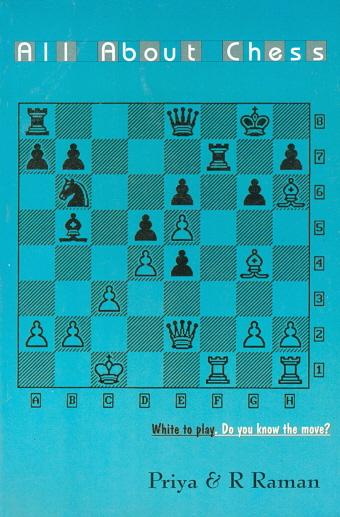

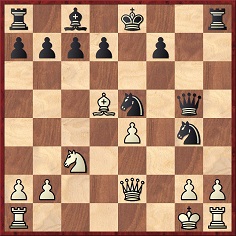

We composed the following little piece of play not as a study or problem but simply as a poser:

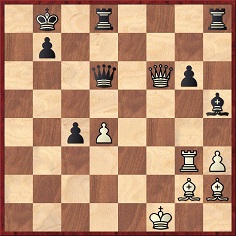

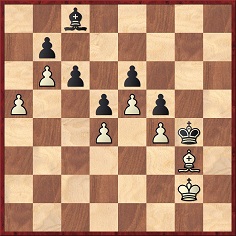

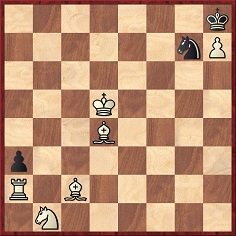

White to move

Find the fastest mating line.

(243)

As mentioned in C.N. 370, the composition is far easier to solve once it is revealed that there is a mate in four.

‘One of the quietest in the whole of chess history, both in this country and elsewhere’ is how P.W. Sergeant describes the year 1893 in his fact-packed book A Century of British Chess (page 219). It was indeed a year of a handful of minor matches and tournaments. No wonder the journalists of the day had so much time and space for the three p’s: poetry, polemics and pap.

(246)

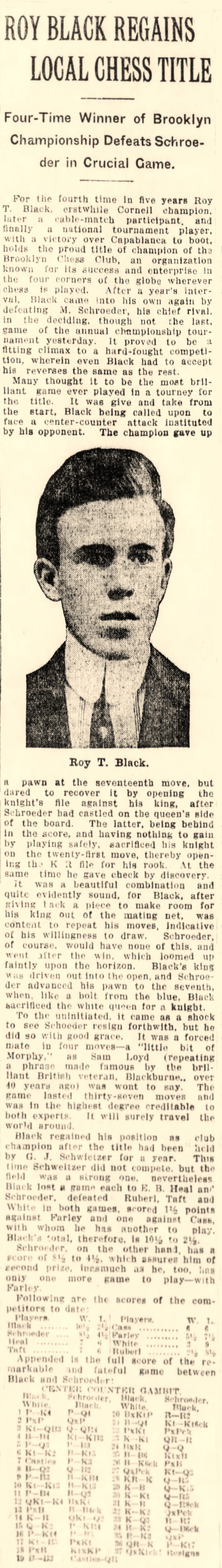

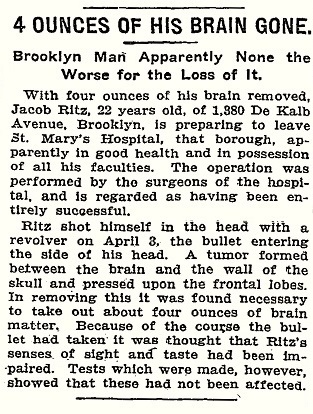

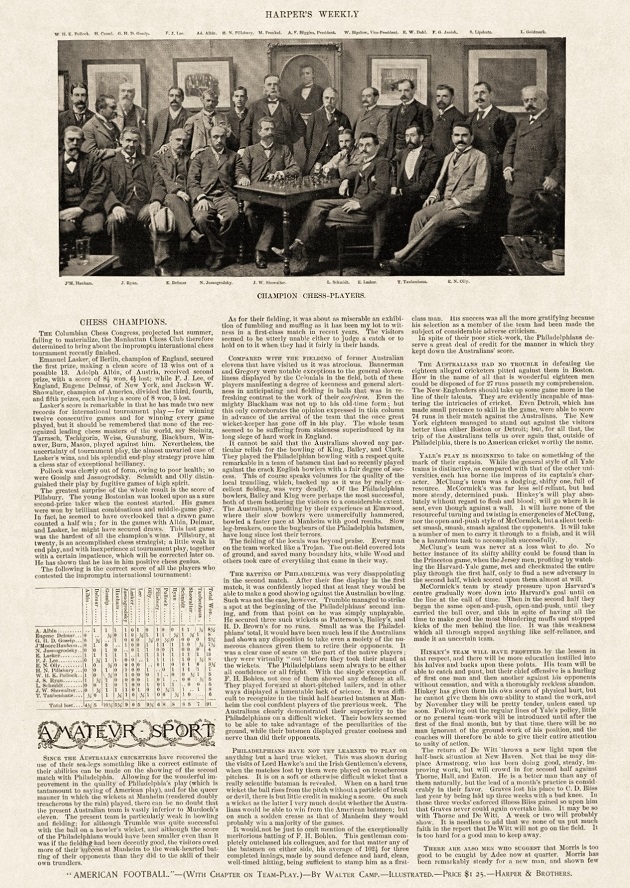

From page 9 of the 10 December 1913 edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

Roy Turnbull Black – Mario Schroeder

Brooklyn Chess Club Championship, 9 December 1913

Centre Counter Game

1 e4 d5 2 exd5 Qxd5 3 Nc3 Qa5 4 Bc4 Nf6 5 d3 Bg4 6 Ne2 c6 7 O-O e6 8 Bd2 Qc7 9 f3 Bf5 10 Ng3 Bg6 11 f4 Bd6 12 Nce4 Bxe4 13 dxe4 Bc5+ 14 Kh1 Nbd7 15 Qe2 h5 16 b4 h4 17 Nf5 exf5 18 bxc5 Nxe4 19 Bc3 O-O-O 20 Bxg7 Rh7 21 Bd4

21...Ng3+ 22 hxg3 hxg3+ 23 Kg1 Rdh8 24 Bxh8 Qd8

25 Bf6 Nxf6 26 Be6+ fxe6 27 Qxe6+ Nd7 28 Rfe1 Qh4 29 Kf1 Qg4 30 Kg1 Qh4 31 Kf1 Qh1+ 32 Ke2 Qxg2+ 33 Kd3 Rh2 34 Re2 Qf3+ 35 Re3 Qxf4 36 Rae1 g2 37 Qxd7+ Resigns.

C.N. 311 gave the game with notes from page 273 of The Year Book of Chess, 1914, which included remarks by Yates. He called 21...Ng3+ ‘An ingenious sacrifice, the effect of which, however, was almost impossible of calculation under a time limit, and for that reason it should not have been made.’

It is the kind of game for which a computer-check is particularly likely to offer surprises.

John Roycroft (London) raises the following interesting topic:

‘We, the serious chess world, could do with a kind of “third world” literature, independent of the disadvantages of Western journalism-cum-illiteracy and equally independent of the disadvantages of East European censorship-cum-controls. Western commentators tend to scoff at, say, USSR chess literature, because the latter's defects are obvious. But the commentators overlook the great values often (far from always!) to be found once the glaring defects (kow-towing to Marx and Lenin, avoidance of “censored” names, glorification of Soviet achievements) are eliminated. Let me take concrete cases. G.A. Nadareishvili has just had a new book “The Study Through the Eyes of Grandmasters" published in the USSR. I first heard of this project from him in 1976. He has worked on it, laboured on it, with incredible conscientiousness, for some six years. This is not unusual. Filipp S. Bondarenko has laboured for much longer to produce the first two volumes of a history of the endgame study. Against great odds (those imposed by the rulers of his own country) he has compiled a most worthy work that no-one has been commercially stupid enough to attempt in the West. But if we could combine the dedication of these authors with the access to libraries and freedom to travel that we take for granted in the West, what wonders would we not achieve. It would put C.N. out of business ... Over-generalizing dangerously, one might say that “we" have the research facilities and the freedom, “they" have the desire for scrupulous accuracy and the necessary level of chess skill. It makes one weep.’

(371)

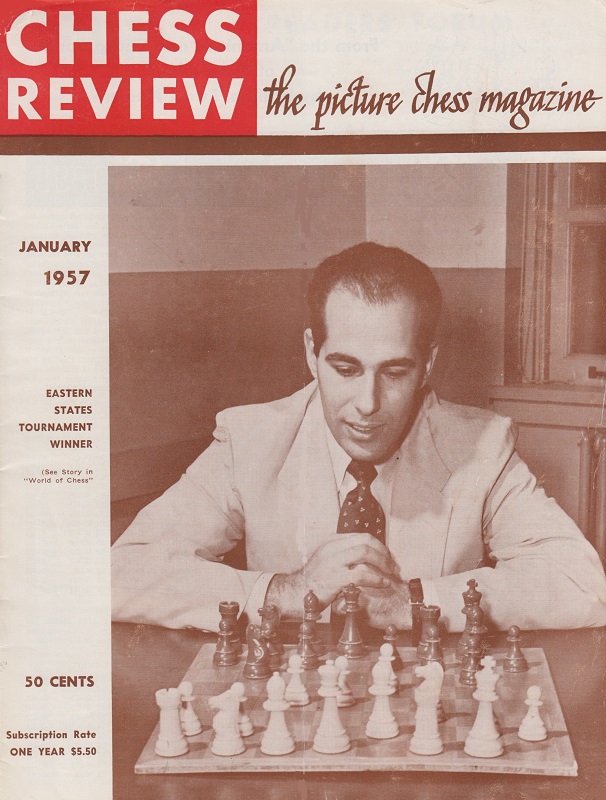

Can there be a more slickly produced chess magazine than this organ of the United States Chess Federation? The production standards are excellent. As for the contents, polls apparently show that its readers prefer packaged feature articles to blanket coverage of chess news, with the result that tournament reports tend to be arbitrary and sketchy. But who is to say that this emphasis is necessarily wrong?

In any case, when a topical event captures the magazine’s imagination, the results are impressive. The reaction to Euwe’s death may not have been quick, but it led to an outstanding issue in April 1982, far the best tribute to appear in any magazine in the world, we suspect. Of the regular articles, ‘Ask the Masters’ is usually entertaining (a format that might be taken up with advantage by the British magazines), while the instructional features also maintain a good standard.

On the minus side, Chess Life’s attitude to the literature of the game is slovenly. Its catalogue loves everything (one loses count of the titles that are a must for every library ...) while the book reviews in the magazine itself are – one must be frank – frequently hideous. Before praising (rightly, but for the wrong reasons, if that is clear ...) A Picture History of Chess, the reviewer writes that ‘Mr Wilson’s idea (of compiling a picture history of chess) is pretty much of a sow’s ear’. Before stating his approval of The Chess Endgame Study another critic starts up: ‘I share with many practical players – and even one well-known grandmaster chess columnist – a distaste for the composed study/problem/endgame genre of chess.’ This disarming honesty is supposed to impress us, but a truly honest critic would have sent his review copy of the book to Pal Benko or somebody else properly qualified to make an intelligent assessment.

Worst of all is the reviewers’ pitiful quirk of ending their prose on a note of chummy illiteracy. Two examples:

‘Hey! Wanna see a two-mover?’ (Jim Marfia)

‘Anyone wanna help me write a chess book.’ (Jeffrey Kastner)

Neither sentence means anything. Chess Life, a good magazine, desperately needs to revise its choice of reviewers and, dare we say it, go rather more up-market.

(496)

The magazine went in the opposite direction, and especially during the period 1985-88. (C.N. 496 was written in 1983.)

On 17 February 2002 Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA) wrote to us:

‘As far as Evans and Parr are concerned, I think what it basically comes down to is that both have some sort of delusions that they know something of chess history, whereas in truth they both know very little. Thus the only real defense they have is scurrilous attacks on those who point out their absurd errors. Schiller belongs to the same slovenly group.

Nothing would surprise me about the USCF. Although I have known some good people in lesser positions there over the years, the people who have the power there are generally little better than guttersniping thieves out to enrich themselves at the expense of the USCF. Note their constant turnover. The publication has been a sorry rag for years and every time they start to improve it, some of their idiotic people ruin it again.’

R.F. Bradley (Donaghadee, Northern Ireland) sends the following from page 167 of the April 1935 BCM:

‘“Will there ever come a day” asks Clarence S. Howell, annotating a game beginning with 1 P-Q4 P-Q4 2 P-QB4, “when this absurdly dull opening is barred? The QP openings have taken all the romance out of chess. The nonsense of it all is that there are 13 ways to play against 1 P-Q4, all of which are good enough to draw. Against 1 P-K4 I do not know (and I believe no master knows) of a certain way to draw.”’

(663)

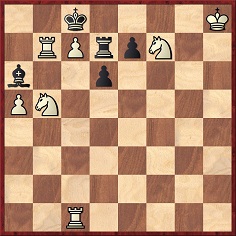

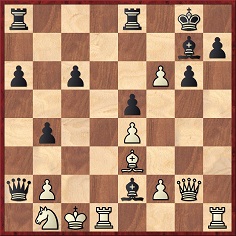

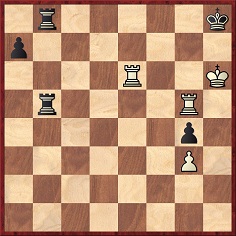

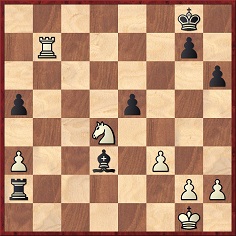

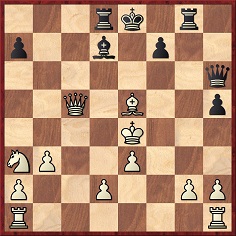

Three unusual finishes:

H. von Gottschall-C. Walbrodt, Kiel, 1 September 1893

White, to move, found the quickest conclusion: 26 Kd2, with three ways of mating on the following move.

Source: tournament book, pages 42-43.

J.R. Capablanca-J. Grommer, New York, 2 July 1913

White exploited his opponent’s back-rank weakness by 39 Re8 Rf4 40 Qb8 Kg8 41 Qb3+ Kh8 42 Rxf8+ Rxf8 43 Qf7 Qc8 44 Qxf8+ Resigns.

Source: American Chess Bulletin, August 1913, page 171.

A. Brinckmann-R. Keller, Bad Oeynhausen, 18 July 1939

White administered the coup de grâce as follows: 27 Rd8 Rxd8 28 Rh7+ Resigns. It is mate in two. A rare double rook sacrifice.

Source: Lachaga tournament book, pages 38-39,

(CHESS, 1985)

In the third position there is a forced mate in six with both 27 Rd8 and 27 Rh7+.

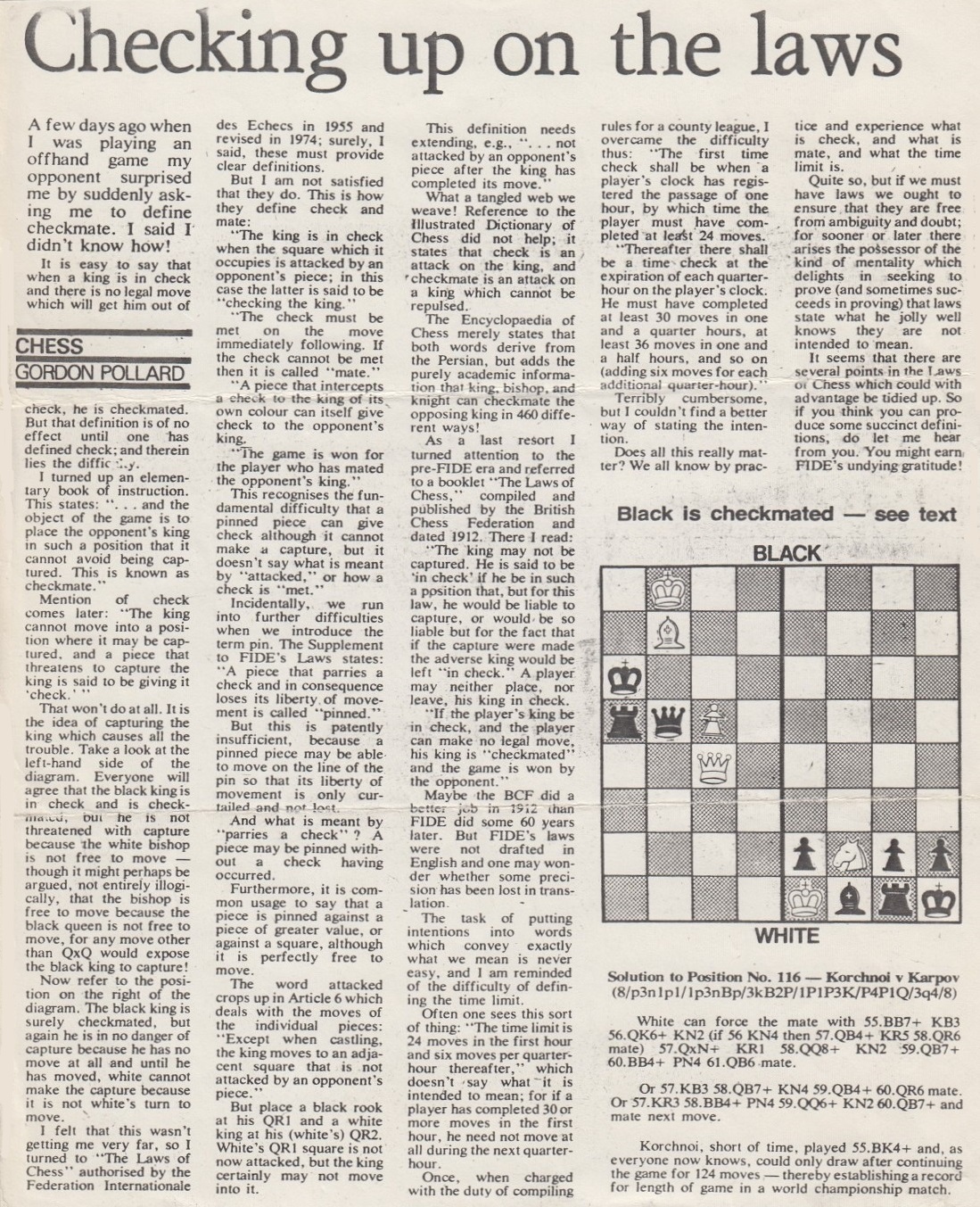

C.N. 107 highly praised the weekly chess column by Gordon Pollard (Wallingford, England) in the Abingdon Herald (also referred to as the ‘Herald series’). Below is an example (column dated 17 August 1978) which he sent us:

In C.N. 107 we wrote:

His chess column in the Abingdon Herald is truly outstanding, and the newspaper itself is to be congratulated on recognizing excellence and devoting to chess a very substantial amount of space.

A reader informs us:

‘You will be surprised to learn that in 1967 Fischer played in an Interzonal held in Sussex. I gleaned this from Idle Passion by Alexander Cockburn (page 178). Did they play the Bognor-Indian? On page 131 of the same work we are told of the “tournament circuit: run-down seaside towns in England, such as Bournemouth or Hastings”.

Idle Passion is indeed a curious book about – well, we are not altogether sure what it is about. A sentence we once noted down from it:

‘Lasker is interesting not so much on the pathobiographical level as on the sociocultural one.’ (Page 55)

It is made up of the kind of prose where it would appear that nouns, adjectives, verbs, etc. were all inserted separately by a different member of the committee, so it comes as a surprise to learn that Alexander Cockburn was single-handedly responsible for all parts of speech. In fact, it turns out to be one of those unlikeable books in which a writer slaps between two covers everything he thinks he knows about chess plus a little bit lifted from the local public library and then tries to give the whole a special, spurious slant – in this case presumably psychoanalysis. The trouble is that Mr Cockburn simply does not know enough about chess to write anything worthwhile; it is bad enough to wade through endless factual inaccuracies, but it is infuriating to find these mistakes then used as the basis of character analysis. On page 61 we read that Capablanca ‘rarely played outside tournaments and matches’. Quite untrue, naturally, since the Cuban was one of the most active players of simultaneous games. But too late. Deep-seated reasons for Capa’s ‘laziness’ are already under Mr Cockburn’s penetrating microscope. Thinking of Reuben Fine’s efforts in this field, we are impelled to ask why it is that writers on chess psychology always get their facts topsy-turvy. Now there’s a real question for the analyst.

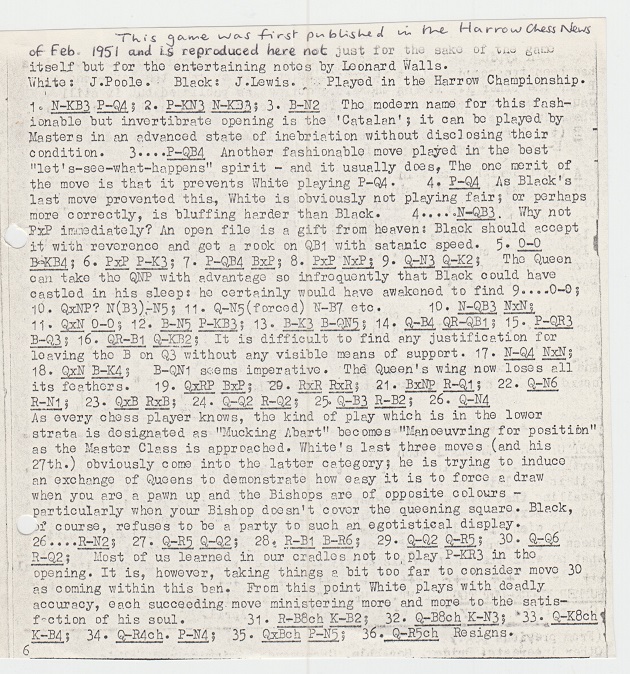

Following publication of a position involving Leonard Walls in C.N. 207 (see also C.N. 5328), Paul Timson (Whalley, England) contributed the following, in C.N. 359:

The Poole v Lewis game: 1 Nf3 d5 2 g3 Nf6 3 Bg2 c5 4 d4 Nc6 5 O-O Bf5 6 dxc5 e6 7 c4 Bxc5 8 cxd5 Nxd5 9 Qb3 Qe7 10 Nc3 Nxc3 11 Qxc3 O-O 12 Bg5 f6 13 Be3 Bb4 14 Qc4 Rac8 15 a3 Bd6 16 Rac1 Qf7 17 Nd4 Nxd4 18 Qxd4 Be5 19 Qxa7 Bxb2 20 Rxc8 Rxc8 21 Bxb7 Rd8 22 Qb6 Rb8 23 Qxb2 Rxb7 24 Qd2 Rd7 25 Qc3 Rc7 26 Qb4 Rb7 27 Qa5 Qd7 28 Rc1 Bh3 29 Qd2 Qa4 30 Qd6 Rd7 31 Rc8+ Kf7 32 Qf8+ Kg6 33 Qe8+ Kf5 34 Qh5+ g5 35 Qxh3+ g4 36 Qh5+ Resigns.

A notable remark by Walls at move 26:

‘As every chess player knows, the kind of play which is in the lower strata is [sic] designated as “Mucking Abart” becomes “Manoeuvring for position” as the Master Class is approached.’

As mentioned in Chess and Poetry, precise sources for the Walls material contributed by Paul Timson are sought, i.e. beyond the fact that the obituary was published in the Middlesex Chessletter.

A letter from Tony Gillam (Nottingham, England) starts:

‘I very nearly wrote to you concerning items in one of last year’s Chess Notes, in particular the strange, primitive comments about book prices. It is best not to comment upon things you know little about. By all means write about it from the consumer’s point of view but assume that the publisher knows his work best.’

Since this magazine has never discussed the subject of book prices we assume that our correspondent will re-direct his remarks as appropriate.

D. Benedek (blindfold)-A. Schweiger, Pécska, 1 January 1905

The game continued: 35 b4 cxb4 36 Rxb6+ axb6 37 c5 bxc5 38 a5, etc.

Source (position only): Wiener Schachzeitung, November-December 1906, page 398.

(353)

On page 24 of Larry Evans’ The Chess Beat Al Horowitz is quoted:

‘Chess is a great game. No matter how good one is, there is always somebody better. No matter how bad one is, there is always somebody worse.’

What other game can match that?

(402)

Switzerland being a notoriously small country, we decided to nip along to the Lugano Open tournament.

By train it turned out to be a six-hour nip, but the journey was well worth it. The eventual winner, Seirawan, impressed by his cool approach, quite apart from the fact that he was one of the few masters whose clothes did not appear to have been put on with a hay-fork. Gheorghiu still has a total aversion to sitting down; he has the air of a Mediterranean barber who has decided there must be more to life than haircuts. Hort squares up to the chess board in the manner of a wicket-keeper, often seeming to rest his chin on d1 (especially if he is White ...). One noted too, without being able to conjure up a satisfying psychological or sociological explanation, that pipe and cigar smokers are to be found only amongst the lower ranks, in the secondary tournament. With the masters it is cigarettes or nothing. Spectators were generally few in number – almost everyone was playing – but amongst those jostling for position behind the railings were a goodly number of dogs and babies (to the extent that either has the habit of jostling). The whole congress was played out in a relaxed, liberal atmosphere.

Of course, it is generally the little things that remain in the mind after such an event. Lugano must be one of the most beautiful places in Europe; the tournament was tenaciously fought out, making it an irresistible combination for the casual visitor.

(439)

So far, most Edition Olms reprints have been of German-language works, a notable and most welcome exception being The Sixth American Chess Congress New York 1889 by W. Steinitz. An exceedingly rare work, Steinitz annotates in it all 432 (!) games played, and the result is a beautiful volume.

Out of the 20 competitors in this double-round tourney, one almost unknown figure fascinated us: MacLeod. As noted on page 50 of Chernev’s Wonders and Curiosities of Chess MacLeod holds to this day the unenviable record of the most games lost in a single tournament – 31. However, as the Preface to this reprint says, MacLeod was only 16 at the time. (Gaige confirms this in his Catalog with a reference that N.W. MacLeod was born in 1872. Afterword: see, however, C.N. 479 below.) And yet we note in Sunnucks’ Encyclopaedia, under the heading ‘Canada’ that N.W. MacLeod had already been champion of that country in 1886 and 1888. Clearly he was quite a prodigy, despite those 31 losses, but what became of him after 1889? It is eerie to think that, theoretically, he could still be alive today ...

At New York he did himself a grave disservice by his choice of openings (1 e4 e5 2 c3, for example, with embarrassing regularity as White). Nevertheless, of his six wins several were of high quality. In the first round [i.e. first cycle] he defeated D.M. Martínez in what Steinitz called ‘a remarkably fine game’; in the second his victory over Gossip received the following praise from the world champion: ‘The ending after queening his pawn is played with surprising ingenuity by the youthful competitor. It was given as a study in various chess columns, and it quite deserved the distinction.’ Later in the tournament MacLeod also took the scalp of Blackburne, after fending off a perilous Danish Gambit attack.

The only reference we have to hand of MacLeod after this date is an extraordinary defeat of Emanuel Lasker in a simultaneous exhibition in Quebec in 1892. Extraordinary, because it must surely be the only game Lasker ever played in which he struggled on in vain when two queens down. (See page 45 of the third Chess Player collection of Lasker’s games.)

(441)

Below is a potted biography of Nicholas Menelaus MacLeod which Jeremy Gaige (Philadelphia, PA, USA) sent us later in 1983 (C.N. 479):

See also Emanuel Lasker Miscellanea.

One of the most spectacular moves of Berlin, 1897 was played, against Marco, by the obscure player Johannes Metger, in the 17th round on 1 October. Because the game ended in a draw (after 62 moves) and no doubt because Metger was little-known, Black’s ingenious 15th move has never received the attention it deserves.

(White: Marco) 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 d4 Be7 6 Re1 Nd6 7 Ba4 e4 8 Ne5 O-O 9 Nc3 Nf5 10 Nxc6 dxc6 11 d5 cxd5 12 Qxd5 Nd6 13 Nxe4 Be6 14 Qh5 Nxe4 15 Rxe4

... and now Metger found the terrific move 15...Bg4. Of course, the bishop is untouchable either way (16 Rxg4 Qd1 mate or 18 Qxg4 f5); White played 16 Qa5.

(453)

On 23 March 1983 Antenne 2, the second French television channel, transmitted a truly fine film on chess, Moeurs en direct: jouer sa vie by Gilles Carle and Camille Coudari, a production of the Office National du Film du Canada and Radio-Canada.

A subtle, artistic treatment of the game, this film included much interview material (not all specially shot) involving Karpov, Fischer, Euwe (one sentence), Fine, Timman, Ljubojević, etc. Karpov spoke in a way suggesting that he had been away at a rehearsal camp for the previous three weeks; the Fischer of the late 1960s and early 1970s scowled and snapped suspiciously when trapped by a reporter and – of course – gave little away in his replies, but at least they were an improvization. Reuben Fine has an endearing habit of chuckling in mid-sentence as he contemplates the bons mots he intends to deliver; in the end, however, all one catches is the chuckle. Arrabal’s contribution was quite simply unwatchable. By contrast, the researcher, Camille Coudari, proved himself a natural performer, many of his extemporaneous observations being remarkably acute.

The programme was graced with much archive material of the old-timers and, whilst full of imaginative visual effects, did not shirk the technical aspects of the game. Coudari’s exposé of hypermodernism was excellent. Keep an eye open for this film; it is thoroughly enjoyable.

Addition on 1 August 2010: Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) comments that Moeurs en direct was merely the name of the French television programme/series and was not part of the title of the film itself (Jouer sa vie).

Addition on 11 November 2018: C.N. 11091 pointed out that the film can be viewed on-line under its English title, The Great Chess Movie.

The book catalogues prepared by Dale Brandreth are of enthralling interest, crammed as they are with acute observations on the titles listed. For example:

‘The Chess Wheel, V. Armen, English Opening. Similar to the circular slide rule. 65 variations. More a novelty than anything else. Rather humorous in that the author has boldly printed on the device that “patent pending for all chess openings and defenses on the wheel system”. What sublime effrontery and ignorance. Did he invent all these lines? No, of course not. Yet he has the gall to try to patent them. The chess world does not lack its buffoons either.’

(472)

Paul Calhoun (West Hartford, CT, USA) writes that the criticism is unfair, and he has sent us a PDF file which presents The Chess Wheel and includes commendations.

(12111)

An ultra-sharp attack from a match between Romania and Latvia:

Ion Gudju – Karl Karlovich Behting

Paris, 1924

Greco Counter-Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 f5 3 Bc4 fxe4 4 Nxe5 Qg5 5 Nf7 Qxg2 6 Rf1 d5 7 Bxd5 Nf6 8 Nxh8 Bh3 9 Bc4 Nc6 10 c3 Ne5 11 d4 O-O-O 12 Be2 Nf3+ 13 Bxf3 Qxf1+ 13 Kd2 Qxf2+ 14 Be2 e3+ 16 Kc2 Bf5+ 17 Kb3 Be6+ 18 c4 Bc5 19 d5

19...Nxd5 20 Bg4 Nf4 21 Bxe6+ Nxe6 22 Qg4 Qf6 23 Nc3 Kb8 24 Ne4 Qd4 25 a3 Qd3+ 26 Ka2 Qxc4+ 27 b3 Rd2+ 28 Bb2 Rxb2+ 29 Kxb2 Bd4+ 30 Kb1 Qxb3+ 31 Kc1 Bb2+ 32 Kb1 Bxa3 mate.

Source: Primera Olimpíada de Ajedrez, page 113.

(CHESS, 1985)

‘Fred Lazard (1883-1949) [sic] the most all-around chessmaster of his time ...’

Source: page 119 of Dictionary of Modern Chess by Byrne J. Horton (New York, 1959)

(512)

Another indispensable entry in Horton’s Dictionary of Modern Chess:

‘HIPPOPHOBIA: A term sometimes applied to chessplayers who dread the presence of knights on the chessboard ... Chessplayers who are afflicted with hippophobia are known to take great risks so as to eliminate their opponents’ knights.’

Horton names no names.

We also like the entry ‘MIDSUMMER MADNESS’: ‘An expression used by the editor of The Field when he referred to Steinitz’s 20th move (20...P-KN4) as “midsummer madness”. No further explanatory comment was given. The game was played between Blackburne and Steinitz in a Vienna tournament.’

It is hard to know what to make of this drivel. But of course the whole affair is devoid of importance, ‘midsummer madness’ being no more worth knowing than ‘hippophobia’.

If our thinking is not too tortuous, Horton makes Sunnucks look like Murray.

(530)

The April 1983 Chess Life (pages 12-13) contains an interview with the former world champion Boris Spassky which concludes with the following, perhaps surprising, quote:

‘Personally, I think the best chessplayer of all time was Capablanca – especially because he was very lazy, and I am lazy too. So I can understand him very easily. But he was a real genius.’

Leaving aside the doubtful logic of this, we imagine nonetheless that Spassky feels duty bound to make such jaunty remarks; if nothing else, it makes good copy for journalists, and such remarks can be truly informative.

This led us to reflect what a shame it is that the great masters of the past gave infrequent interviews and scarcely any press conferences. How one would have loved the chance to interrogate Morphy. Nowadays Karpov gives almost as many interviews as he plays games, and has learned to perfection the requisite skills. The Edmondson book mentioned in C.N. 509 [Chess Scandals] gives a three-page transcript of a press conference in Baguio City. To the assembled newshounds Karpov showed himself to be charming, unassuming, discreet, reasonable and diplomatic in best Sebastian Coe fashion. None of the above adjectives is particularly appropriate for Korchnoi, who acts more like a human being, relishing his new-found freedom of speech.

(540)

Michael McDowell (Newtownards, Northern Ireland) reminds us of the following from the introduction to the 22nd round in the New York, 1924 book (presumably written by Helms):

‘And so Alekhine remained undisputed third with a score that would have made him the winner of the tournament, barring the presence of Dr Lasker and Capablanca!’

There’s no arguing with that.

(546)

Another example of this theme, from page 4 of The Monte Carlo Tournament of 1903 by Emil Kemény (1860-1925), which has been reprinted by Edition Olms:

‘Had Dr Tarrasch scored 1½ points less – as could have been very readily the case – Maróczy would have won the first prize, and the victory would have been considered a fairly decisive one ...’

(623)

From Albrecht Buschke (New York, NY, USA):

‘A beautiful reprint of the Karlsbad 1929 tournament book was published a few years ago, long before the Olms edition, by Dale A. Brandreth. To avoid such unnecessary duplications of “reprints” there should be a clearing house for reprint publishers. Lasker’s Common Sense in Chess (since not copyrighted) was reprinted again and again by one obscure publisher after the other, one adding misprints to the misprints of his predecessors until, finally, almost simultaneously, Tartan books (McKay) and Dover published so-called reprints – Tartan with all the mistakes accumulated by previous pirate reprinters, Dover in the bowdlerized version by Fred Reinfeld.’

(590)

An invitation to heresy: are there any famous games that readers consider grossly over-rated? Personally – and it is hard to get more heretical than this – we have never been much taken with the Réti-Bogoljubow brilliancy-prize game at New York, 1924.

(614)

Are we alone in being surprised at the brilliancy-prize award to Polugayevsky against Torre in the recent [1984] London Phillips and Drew tournament? Was there much more to it than routine crash-bang?

(810)

From the Summer 1955 Chess Reader, in which Ken Whyld reviewed Tartakower and du Mont’s 100 Master Games of Modern Chess:

‘It is curious to see once more the game Golombek-Brown, in which White wins by means of a neat but obvious piece sacrifice. From the excessive number of times it has been published, future generations must think it highly esteemed in our day.’

(1338)

From an article ‘Chess in Fiction’ by Stewart Reuben in the October [1984] CHESS:

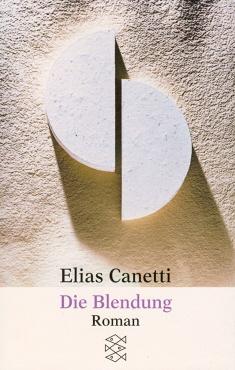

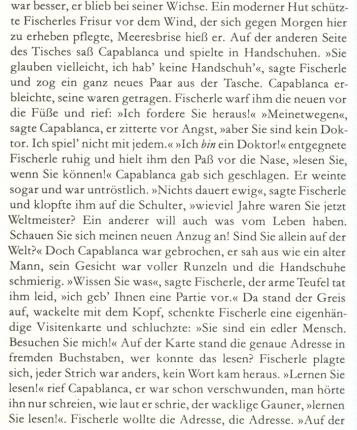

‘Auto da Fé by Elias Canetti, the 1981 Nobel Prize Winner for Literature, is a real curiosity. One of the main characters is called Fischer. He dreams of being World Chess Champion, buying new suits from the best tailors and building a giant palace with real castles, knights and pawns. So what?, I hear you ask. The book was written in 1935 long before Bobby Fischer was even born! It may be possible to reduce the coincidence slightly. It is true Fischer was extremely concerned about his clothes at one stage of his career. But he always denied that he said much of what Allen Ginsberg [sic – Ralph Ginzburg] reported in his interview with Fischer. Perhaps Ginsberg [sic] knew of Auto da Fé and fooled the world. Still, an extraordinary coincidence.’

(621)

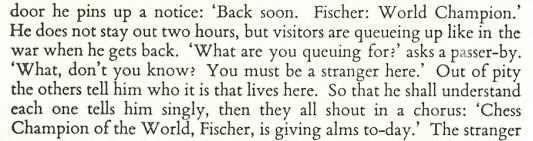

The chessplaying Fischerle/Fischer coincidence in Elias Canetti’s 1935 novel Die Blendung (published in English in the 1940s under the titles Auto-da-Fé and The Tower of Babel) is too well known to be discussed here, but when and by whom was the coincidence first pointed out, and did Canetti ever comment on it?

Above is an excerpt from page 380 of the 2005 Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag edition, while the passage below comes from page 200 of Auto-da-Fé:

(5507)

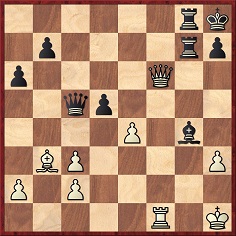

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 5 O-O Nxe4 6 Bd5 Nxf2 7 Rxf2 Bxf2+ 8 Kxf2 Ne7 9 Qb3 O-O 10 Be4 d5 11 Bc2 e4 12 Ne1 Ng6 13 c4 d4 14 Qg3 f5 15 Kg1 c5 (The ‘perfect’ centre.)

16 d3 f4 17 Qf2 e3 18 Qf3 Qh4 19 Qd5+ Kh8 20 Nf3 Qf2+ 21 Kh1 Nh4 22 Qg5 Bh3 23 White resigns.

Source: tournament book, pages 254-255.

(684)

‘Who was the greatest player ever?’ was a question Joseph Platz once (1963) asked Gligorić. The answer was Morphy (Chess Memoirs by Platz, page 133).

From the book we take this game:

Joseph Platz – L. Noderer

Hartford, 1966

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nd2 c5 4 exd5 exd5 5 Ngf3 c4 6 c3 Nf6 7 Be2 Bd6 8 O-O Qc7 9 b3 cxb3 10 Qxb3 O-O 11 c4 dxc4 12 Nxc4 Be6 13 Qd3 Bxc4 14 Qxc4 Nc6 15 Be3 Ng4 16 d5 Bxh2+ 17 Kh1 Nxe3 18 fxe3 Na5 19 Qa4 Bd6 20 Bd3 b6 21 Bxh7+ Kxh7 22 Qh4+ Kg8 23 Ng5 Qc2 24 e4 Resigns.

(690)

Rule XII from the New York, 1889 tournament book:

‘... Consultation and analyzing moves on a chess board during the adjournments are strictly prohibited, and any competitor proved guilty of the same shall be expelled from the tournament by a three-fourths vote of the Jury.’

(705)

Adriano Chicco (Genoa, Italy) sends a game from pages 216-217 of the Revista Scacchistica Italiana, August 1901. Girolamo Tassinari’s play is typically sharp and rather ahead of its time (exploitation of the opponent’s weaknesses) and, indeed, the annotator remarks that the game seems as if it were played yesterday.

Girolamo Tassinari – Arnous de Rivière

Paris (Café de la Régence), 3 September 1853

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Bc5 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 c3 Nf6 5 O-O d6 6 d4 exd4 7 cxd4 Bb6 8 Nc3 O-O 9 h3 Ne7 10 Bg5 c6 11 e5 Ne8 12 d5 dxe5 13 Nxe5 Nd6 14 dxc6 Nxc4 15 Nxc4 (Position rather than material.) 15...Qxd1 16 Raxd1 Nxc6 17 Nxb6 axb6 18 a3 Be6 19 Be3 Bc4 20 Rfe1 b5 21 Ne4 Bb3 22 Rd7 Na5 23 Nd6 Bd5 24 Bc5 Rfb8 25 Bb6 Nc4 26 Nxc4 Bxc4 27 Ree7 (Nimzowitsch’s seventh rank.) Ra6 28 Rxb7 Kf8 29 Bc5 Rxb7 30 Re6+ Resigns.

(712)

Europe Echecs (April 1984) reports the death of François Le Lionnais on 13 March. Even if his Dictionnaire des échecs – much praised – was in our view a disappointing work, Le Lionnais stands out as one of the most stylish French chess writers ever. What a pity, though, that the French language has contributed so little of any worth to the literature of the game.

(724)

We thank J.J. Walsh (Dublin) for sending a collection of curiosities, quotes, quizzes, etc. that he has assembled. Our favourite item was a six-page spread of aphorisms and general observations on the game. For example:

‘Rook endings a pawn up are generally drawn – but rook endings a pawn down are usually lost.’

‘The most attractive combinations are usually just one tempo short of being sound.’

‘The popular press believes that chess congresses are composed exclusively of child prodigies and octogenarians.’

‘Players indicate an increasing maturity at the game by not automatically making the en passant capture.’

‘Players with the greatest theoretical opening knowledge are most likely to get into time-trouble.’

‘The weakest players in a tournament are generally first to enquire about the prizes.’

‘Annotations attempt to prove that a game had only one logical sequence.’

Mr Walsh also repeats the old story about Capablanca having the tournament hall cleared of spectators before resigning to Marshall at Havana, 1913. But is there any more truth to it than there is in the old yarn about Alekhine ‘smashing up his hotel furniture’ at Carlsbad, 1923?!

Another item about the same two masters requires slight amendment. We read:

‘Capablanca and Alekhine, two outstanding world champions and contemporaries, had curiously similar careers. Each was born during the month of November – Capablanca 1888 and Alekhine 1892 – and both died at the same age, 53 years, also in the same month, March – Capablanca in 1942, Alekhine 1946.

A further coincidence was the fact that four years after Capablanca’s birth in Havana a world championship match Chigorin v Steinitz was held in that city, while four years after Alekhine’s birth in Moscow, Lasker played a world title match with Steinitz there.’

All perfectly true, except the point that Alekhine was not born in November. (Correct date 19 October (old style), 31 October (new style).) We suspect that the source of Mr Walsh’s misinformation was an article in the July 1976 CHESS (page 316) by a notoriously undependable old hack.

(775)

The first quotation in C.N. 775 serves as a reminder of the following from Seirawan by Vincent McCambridge (Players Press), page 47:

‘Korchnoi is renowned as the world’s best endgame player – Yasser once told me that, in blitz, Korchnoi wins all endgames equal or slightly inferior for him. “With a huge endgame edge”, said Yasser, “I can generally draw him!”’

A methodically annotated collection of the American’s games, Y.S. being described by the author as the most exciting chess figure since Fischer. US chess figure may or may not have been meant. The notes are objective (Seirawan is not portrayed as an unerring genius effortlessly disposing of morons), which only adds to the mystery of why McCambridge gives a single Seirawan loss – to himself. The game is not even well annotated.

(816)

From the 1935 BCM, page 364, a review of Reinfeld’s book on Cambridge Springs, 1904:

‘It is a curious fact that the particular move of the Queen’s Gambit Declined, which has earned for it the name of the Cambridge Springs Variation, has so as far as we can see no reference as such in this book.’

See also page 192 of the May 1984 issue of the same journal.

(779)

The BCM quote in C.N. 779 must be based on a series of complete oversights. Parley Long (Cambridge, OH, USA) sends photocopies from Reinfeld’s book of Cambridge Springs, 1904. 6...Qa5 was played several times.

(794)

‘Pressure on space is cruel’, writes the diplomatic magazine editor when declining to publish a would-be contributor’s precious prose. Cruelty is at its peak if the offering is mere peripheral matter, i.e. not hard chess news. It is considered self-evident that subscribers to a general chess magazine will, above all else, want to know what is going on now.

How true this is may be open to doubt. And what in any case is ‘chess news’? Tournament and match results? If so, down as far as which level? National championships, county ... state ...? Of course the editor is caught either way. Either he will be accused of skimpy news coverage or else of heavy-handed blanket treatment. Should he be writing just for present-day readers, or trying to produce a journal of permanent record?

In general there is probably far too much emphasis on minor players, especially from the magazine’s own country, at the expense of the really top players, as used to be the case. As previously noted in this magazine, our ignorance about the careers of the real ‘greats’ of today is deep indeed.

Editors will doubtless reply that the days are gone when they could consecrate three or four pages to the retelling of every dull detail of the life of some particularly philanthropic, if non-chessplaying, patron of the game. Nonetheless, space is not always well used. One growing trend we perceive is the interminable personal report on a tournament by a participant, by dint of which what would have been a couple of columns is suddenly transformed into several pages.

If well done, the personal report is fascinating and even indispensable, but there are grave dangers not only of distorting the amount of space left over for other events but even of distorting the ‘main event’ itself. Paris, 1983 was a major success for Jim Plaskett, but you would hardly guess as much from Tim Harding’s report in the July 1983 CHESS. He made himself the star. And pity poor Sax, who scored a tremendous triumph at Lugano, 1984; John Nunn’s report in the May 1984 BCM (four pages) barely mentioned him.

But news is not just results. Deaths of major figures are often passed over with degrading brevity, and it is not simply a matter of information not being available. Europe Echecs rarely has obituaries, although François Le Lionnais was accorded eight large pages. CHESS seldom gives more than a line or two, and sometimes, as in the case of Wolfgang Heidenfeld, not even that. To be noticed by Chess Life one must be either American or a world champion.

We have mentioned previously the way new books, events and trends in the publishing industry etc., are given scant attention, the BCM being (as with obituaries) an honourable exception. But are not deaths and books just as much news as minor tournament results?

These random thoughts, which readers are free to contradict in future issues of C.N., may be seen in the context of a new magazine which, though so far only at issue zero (i.e. the ‘free introduction’ issue), shows considerable promise.

New in Chess goes some way towards our ideal of a truly international magazine (or, as the introduction puts it: ‘We do hope to fulfil a need, felt by many inhabitants of the chess world for a truly international medium, that passes the borders, so often visible in the rest of the world’). It does, nevertheless, have a certain Anglo-Dutch bias (the magazine appears in English and Dutch language versions) which might suitably be reduced even further. Although introductory issues are liable to be misleading, the start is promising indeed, despite the absence of book reviews, obituaries, features on specific phases of the game, endgame studies, problems, etc.

There is a risk that New in Chess, like Brady’s Chessworld, will prove too luxuriously produced to keep going; not only is plushness expensive, but it normally means a lengthy printing process which costs the journal a certain topicality and freshness.

The only serious fault in New in Chess is its standard of English and proof-reading. A note by Korchnoi after 1 e4 reads: ‘I have spent about ten minutes in thought here. My partner works a lot into chess to counter all modern variations. He was certainly prepared to everything, I used to play in the past: Open Spanish, Sicilian, French ...’ (page 10). An article by Wim Andriessen has dates incorrectly printed. And how about the following jewel in a report on the Reykjavik Open: ‘When Reshevsky received his prize he got a scanding applause with kept on for minutes’. Sic, sic, sic.

The highlight of issue zero is a most extraordinary interview with Botvinnik. Our eye homed in on a quote, ‘Capablanca was a genius, the greatest genius in the whole history of chess’, and we at once felt well-disposed to the former world champion, ‘Mr Soviet Chess’. But the rest of the material makes Botvinnik a difficult man to like, the interview being a supreme example of high bitchery.

Karpov is ‘an exploiter of other people’s ideas. His ability to use these ideas is not at issue, but he himself is about as fertile as a woman who has been sterilized’. Portisch and Polugayevsky ‘have no talent for real research’. Balashov ‘is dull-witted. When he comes into unknown territory he is as defenseless as a kitten’. Karpov ’cannot just force Roshal, who writes all his books for him, to develop a new chess idea for him’. Kasparov’s games ‘are the only ones I still play over’. I hardly talk to the grandmasters here anymore. Nor to the Chess Federation of the USSR’.

The magazine quotes Spassky’s reaction: ‘It is typical of Botvinnik, that he wants to destroy chess, after giving up his own career as an active chess player.’

Certainly Botvinnik adopts a most surprising anti-Soviet stance, and even makes a point of mentioning the dreaded Korchnoi: ‘Of the top chess players of the moment I would like to mention two names: Korchnoi and Kasparov.’ He even permits himself an analysis of Karpov’s divorce: ‘It was not a real divorce. She just left him. When two people are not in love they separate automatically.’

Up until a few years ago Botvinnik was a dull case for historians, psychologists, etc., but his recent writings and interviews reveal an unknown, or neglected, side of his character. The interview is an amazing document, and a memorable scoop for New in Chess. News indeed.

(825)

See too C.N. 8192.

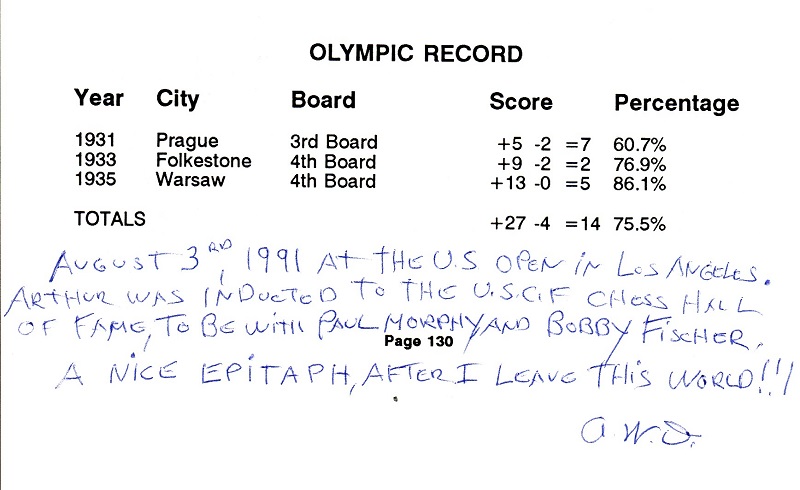

George H. Hudd (South Croydon, England) informs us that a recent biography of Arthur Ransome claims that he played chess with Lenin. Our correspondent goes on to ask who is or was the best player among Heads of State.

(833)

The title above is, perhaps, rather misleading since we are not concerned here with the value of chess history per se, but rather with the practical question of what it has to offer to the average player, the mass of ordinary chess enthusiasts. And ‘history’ we are going to interpret in its loosest sense. Although purists might be shocked by such a pragmatic approach, it has to be recognized that no-one has a duty to be impassioned by the game’s heritage. What, then, does a study of the past offer the average congress entrant? We are almost tempted to suggest more than a study of the present.

It is illogical of a budding 1984 amateur to believe that he should study exclusively, or even principally, the great masters of 1984. Why Karpov more than Botvinnik? And why Botvinnik more than Lasker? Indeed, if one is going to concentrate on a particular champion, why not pick one whose complete career can be studied?

There are probably three main reasons why chess ‘fans’ are reluctant to look back into even the most recent past. The first is a matter of simple actuality, of being interested in hot news. Nothing could be more natural – not that it is a taste we particularly share personally – but it is far from clear that what is interesting for its topicality is also the best practical means of improving one’s game. What will offer more to the student: the bulletin of the 1984 National Championship or the tournament book of New York, 1924?

The second reason is a feeling that because chess is more popular today, the standard of the best players will also be better. Here too illogicality reigns. As previously discussed in Chess Notes, the quality of play of the top few bears no relation to how popular the game is, or how well people play it, at the bottom end. An analogy with music clarifies the point: there has been a vast ‘democratization’ of music with opportunities for the young that were undreamed of by previous generations. Yet another Mozart has never been produced, even though he has been there for two centuries for everybody to learn from.

Let us imagine, however, that one rejects the view of Botvinnik that Capablanca was the ‘greatest ever’ and believes ‘the moderns’ to be better. Would even that be any justification for neglecting the patrimony? What a mighty conceit on the part of a modestly graded player to assume himself capable of learning more from Karpov than from Capablanca because of the former’s ‘discernible’ superiority.

The third reason – and here we hope readers will not groan – is the current misguided obsession with opening theory. As Leonard Barden wrote in the Financial Times of 4 August 1984, 'some theoretical books convey the impression that serious analysis only began with the launch of Chess Informant in the 1960s’. Study the moderns – and not necessarily even the best of them – and your play will soar as you instantly grasp the intricacies of the openings; study Steinitz and you waste your time on nonsense such as 3...d6 in the López, which no-one has seen for decades.

Here also is a foolish conceit; the notion that opening innovations (perhaps at move 15 or 20) by (we choose a name at random) Walter Browne have the remotest relevance to the games of the regular club player. Might it not be better to study 3...d6 after all and catch your opponent unawares? By concentrating on modern games for the sake of opening theory one misses out on the problem-solving intellectual exercise that chess is supposed to constitute, and which is intended to bring pleasure. The opening is, or ought to be, too interesting to be skipped.

Far from seeing the past as a desert, we would point out an important, if obvious, reason why it might be viewed as even more important for study than the present: there is more of it – perhaps a century and a half of the richest terrain. And not only the games, but also the grand literary productions. Alekhine’s writing was of such quality that it is almost unbelievable that he does not merit automatic pride of place on players’ bookshelves. A good question for club night: ‘Hands up those who have read Steinitz? Or Tarrasch ...’ But then, neither will be much help on the latest Sicilian wrinkles.

(834)

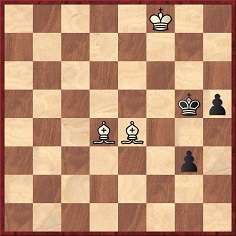

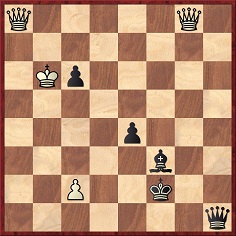

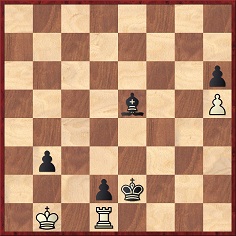

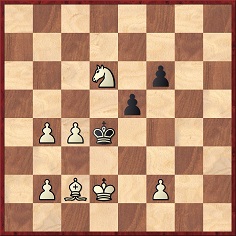

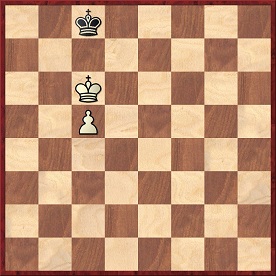

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) offers the following four-non-mover composed by A. Rautanen, 30 Shakkiprobleemaa, 1929:

White mates without moving

The composition was quoted in a lecture entitled ‘One good turn ....’

(865)

The solution is given at the end of this Chess Jottings article.

We always welcome readership reaction, even if – especially since – much of it is contradictory. C.N. has been called ‘over-serious’ and ‘the funniest chess magazine I’ve ever read’ (!). We are still reeling from a single postal delivery that brought letters informing us that we were a) ‘incredibly naive’ and b) ‘a cynical expletive deleted’. Too many/not enough games/problems are other remarks difficult to reconcile. The ‘Batsford business’, our fil rouge over what seem like decades, has drawn forth a variety of reactions. Most readers have professed themselves in agreement with our views, some even being ‘gripped by the saga’. The May 1984 Chess Life, however, praised C.N. ‘lengthy vendettas with publishers notwithstanding’. The notion that it might be worthwhile for a journal with no book-selling ties to scrutinize chess publishers’ activities was not considered.

(871)

The view of Martin Amis, in The Observer, 23 December 1984:

‘Of course one shouldn’t forget that the game of chess, for all its radiance, artistry and deep fascination, is essentially a trivial pursuit. It is without content. Thus the “history” of chess is of no more intrinsic interest than the history of punting or thumb-twiddling or nose-picking. But it does have a history, and so books about it will continue to appear. The subject already has the peaceful glow of scholastic futility. One of the great things about chess is its refusal, not its readiness, to serve as a paradigm for anything else, as Freudians, Marxists et al. have frustratingly found. Chess is what it is and not another thing, it is only a game.’

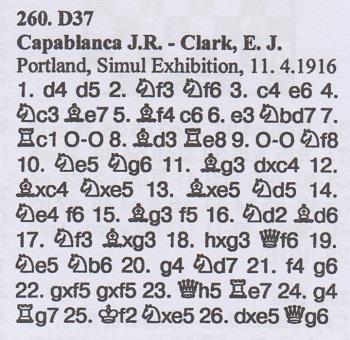

(902)

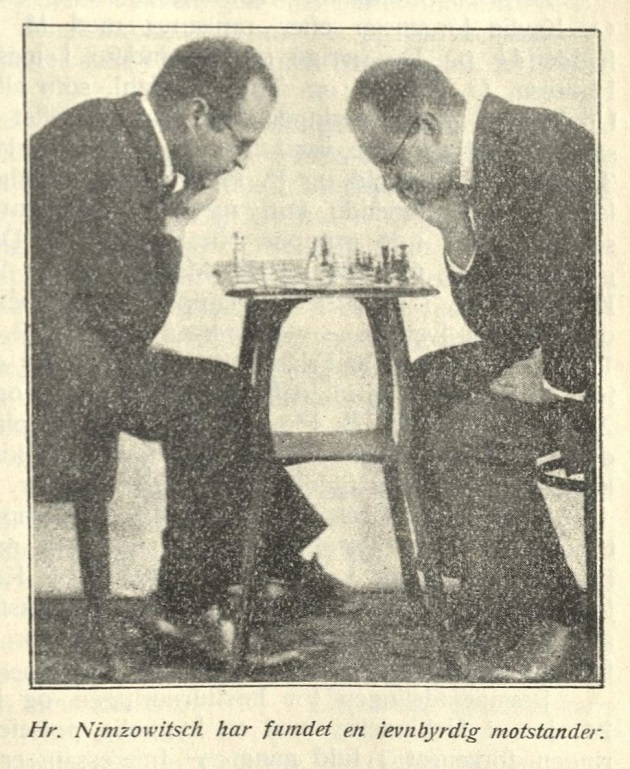

Despite Nimzowitsch’s well-known dislike of tobacco, page 87 of Visiting Mrs Nabokov by Martin Amis (London, 1993) affirmed that ‘Nimzowitsch used to smoke an especially noxious cigar’.

We have now found a much older and more extensive version of the alleged Nimzowitsch observation discussed in C.N.s 3197 and 3200. From pages xiv-xv of Chess Openings by James Mason (London, 1897):

‘A threat or menace of exchange, or of occupation of some important point, is often far more effective than its actual execution. For example, in the Ruy López impending BxKt causes the defender much uneasiness. He is, to some extent, obliged to confound the possible with the probable; while yet at the same time in serious doubt as to what may really happen.

Consequently, when you are attacking a piece or pawn that will keep; when you cannot be prevented from occupying some point of vantage, from which your adversary may be anxious to dislodge you; when you can check now or later, with at least equal effect; in these and all such circumstances – be cautious. Do not play a good move too soon. For when you do play it, the worst of it becomes known to your antagonist, who, then free from all doubt or apprehension as to its future happening, is enabled to order his attack or defence accordingly. Therefore reserve it reasonably, thus stretching him on the rack of expectation, while you calmly proceed in development, or otherwise advance the general interests of your position.’

(3257)

In Visiting Mrs Nabokov the article by Martin Amis, on pages 83-93, was entitled ‘Chess: Kasparov v. Karpov’. It originally appeared under the title ‘The Masters and the Mafia’ on pages of 17-18 of the Observer Review, 27 July 1986.

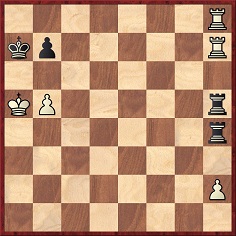

A good beginners’ work is The Batsford Book of Chess by Bob Wade, a revised edition of Playing Chess, that neatly produced if floppy paperback of a decade ago. Whereas Levy and O’Connell would appear to have written Instant Chess in a weekend, Wade’s book represents the culmination – and the accumulation – of a lifetime’s teaching experience.

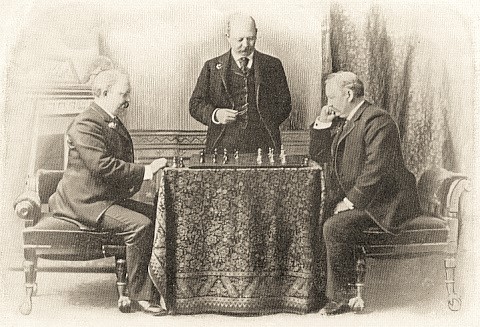

A valiant attempt has been made to keep the new format version as well illustrated as Floppy; however, too many of the photographs of the chess personalities are of poor quality or too dark. The one on page 89 is particularly shady:

Reliable as Wade is on all technical aspects of chess, there is a most unhappy slovenliness on other matters of detail. A remark on page 20 about the possibility of publishers having to speed up the ‘inevitable change’ from descriptive to algebraic notation hardly strikes the reader as a 1984-type observation. One’s worst fears are confirmed on page 133 when the author fails to record Euwe’s death, which has occurred in between the two editions.

There is no justification for the statement on page 70 that Edward Lasker (in 1912) was an American. He had never even visited the New World at that time. Little care has been taken over name spellings towards the end of the book: ‘Kieseritsky’ (pages 111 and 112), ‘MacDonnell’ (pages 121 and 122), ‘Federation International des Echecs’ (page 155), ‘Jaque’ (page 158), ‘Bleyavsky’ (page 159), ‘Nenarakov’ (page 160), and ‘Nimozowitsch’ (page 160). Even the back cover misspells the name Hartston and the title of Golombek’s Encyclopedia.

Other rough edges include a reference on page 102 to a bibliography on page 158 which does not exist, the incorrect implication on page 122 that the ‘Immortal Game’ was played in the London, 1851 ‘even’ [sic], and the inclusion on pages 147-152 of the discredited Adams-Torre game.

Such defects could so easily have been avoided. They tarnish an otherwise well-written book.

(927)

A later (1991) edition was equally lax. See Kingpin, Autumn 1993, page 37.

Colin McGuigan (Newtownards, Northern Ireland) offers a couple of good’uns from David Spanier’s Total Chess:

Page 72: ‘One of the minor absurdities of FIDE is that while the Soviet Union has only one vote, the British Isles have four! England, Scotland, Wales and the Channel Islands.’

Page 73: ‘The Soviet Union’s own contribution ... was to send players out to the Third World, to give simuls and exhibitions and lectures. Taimanov ... went to Indonesia, Suetin to Nigeria, Kondratiev to Zimbabwe, Geller to Ireland and so on.’

(951)

The minutes of the 1984 FIDE Congress reveal that the British Grandmaster Michael Stean was censured for participating in last year’s South African Open Championship. To add to his sins, he won and settled the proceeds of his participation ‘on trust for the benefit of black chessplayers in South Africa’. A recent South African Chessplayer has a lengthy article lamenting FIDE’s reaction and even criticizing one familiar British figure for hypocrisy and vote-catching. We look forward to reading the British chess press’s accounts of the dispute.

(971)

We are grateful to Jerome Bibuld (Port Chester, NY, USA) for a large amount of documentation relating to South African chess, though it is not possible to go into the details of such matters in these pages. On the specific topic mentioned in C.N. 971 our correspondent informs us that as of 11 August 1985 ‘Black chess’ had seen none of the money referred to.

As far as we are aware, the entire affair has been passed over in silence by the British chess press.

(1163)

From Harold Edwin Price (Johannesburg, South Africa):

‘It was something of a shock to read in C.N. 1163 the scandalous and totally untrue allegation by Mr Jerome Bibuld that as of 11 August 1985 “Black” chess in South Africa had seen nothing of the money left in trust by International Grandmaster Michael Stean after he won the 1984 S.A. Open. I am the trustee of that fund. Mr Bibuld’s statement may have caused my reputation considerable damage, and Mr Stean a certain amount of anxiety. It is most regrettable that you have seen fit to give such a disgusting and slanderous (if not, in fact, actionable!) allegation a very broad audience without, apparently, making any serious attempt to investigate its validity.

The simple and easily verifiable facts are these:

1) The interest on the Trust had amounted to about R280 by mid-1985.

2) By August 1985, R216 had been disbursed to various recipients. The grants related to three separate tournaments during the period. (During the subsequent ten months a further R194 has been distributed.)

3) Thus far, not a single request to the fund for assistance has gone unsatisfied.

4) Every cent has gone to “Black” chess – as mandated by the Trust.’

(1184)

Mr Bibuld informs us that he had a debate with Mr Price in Hollywood on 11 August 1985 which was attended by all members of the USCF Policy Board (except Myron Lieberman):

‘During the debate the issue of the Stean “gift” was raised, and I declared that the money had found no takers in the “Black” community (using the broader definition of “Black”, that is, all whom Mr Price etc. would call “non-white”). Further, I declared outright that the money had been returned to the Oude Meester Chess Foundation (whence it had come). Mr Price took much umbrage at my remarks, just as he did in C.N. 1184, enlightening all present with the information that the Oude Meester Chess Foundation (of which he was a member, as then President of the SACF) had entrusted the money to him and that he had set up an escrow bank account (in his own name). Mr Price said nothing about accrued interest or about “R216 [that] had been disbursed to various recipients”. Did he forget to mention this telling point during our debate, in which he was trying to gain support by the Policy Board of the USCF for apartheid chess? I don’t think so, because I recall his saying that the money was waiting for the proper parties to claim it.’

(1297)

An item on page 266 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

On page 9 of The Moscow Challenge Raymond Keene wrote that it was ‘staggering’ that Steinitz had an ‘abysmal’ tournament record in his period as world champion (1886-94). The truth is that Steinitz did not play in a single tournament during the period under consideration.

(976)

On page 256 of the June 1985 BCM Mr Keene made the astounding claim that ‘in calling Steinitz’s tournament record “abysmal” he was criticising it on the grounds of lack of activity’. By that logic, we pointed out on page 305 of the July 1985 issue, given that Fischer has played in no tournaments since 1970 his tournament record since then could be labelled ‘abysmal’.

For further details see Cuttings.

With a major musical and a prestige film about chess, the game is doing well for general publicity.

La Diagonale du Fou (Dangerous Moves) concerns a world championship match between an ageing Petrosian/Karpov figure and a dynamic dissident apparently based on Korchnoi/Fischer. Although without a fraction of the wit, charm and depth of the musical ‘CHESS’, it is enjoyable and gripping enough for an outsider’s view.

The fine photography shows that Geneva is as photogenic as ever, but the film also illustrates how difficult it is to ensure realism when presenting chess to a wide public. The moves are played at such speed that one might think it a match for the world blitz title, while the idea of the world’s top two players informing each other when a move gives check is also difficult to accept. There is ample opportunity to get to know the audience, which appears glued to the same seats throughout the match. The challenger has a bizarre second who, though capable of instantly spotting a mate in seven, does not know the name of the opening that begins 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 c3. Perhaps he was preoccupied with writing an illicit book on the match.

(1014)

C.N. 1726 reported that we had jotted down this position from the 1984 film La Diagonale du Fou/Dangerous Moves:

Black played 1...Qxh3+

The closing credits stated that Nicolas Giffard had created the games shown in the film.

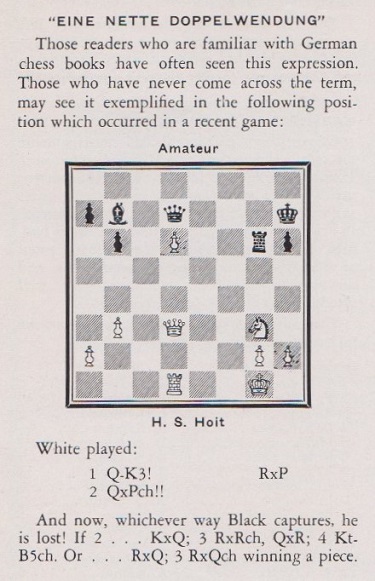

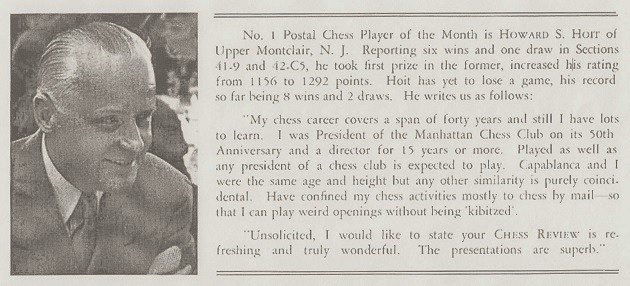

In C.N. 1838 the late Jack O’Keefe pointed out that, with colours reversed, the position was almost identical to one published on page 134 of Chess Review, June 1938 (H.S. Hoit v Amateur, ‘a recent game’):

As mentioned on page 5 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, the Hoit ending was also on page 33 of Combinations The Heart of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1960) and on pages 133-134 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949). The former work gave no details beyond ‘Hoit-Amateur’, and the introductory note read:

‘Chess can be brutal! Black’s king and queen are forced to move to the sixth rank, where a vicious knight lies in wait, poised for the kill.’

The first comment in The Fireside Book of Chess:

‘From a game Hoit-Amateur at New York, in 1938. The winning combination is so elegant that it gives the impression of being a composed ending. Only unique and felicitous chance can produce such exquisite possibilities in practical play.’

The conclusion was given too, without even Hoit’s name, on pages 133-134 of Reinfeld’s The Secret of Tactical Chess (New York, 1958), billed as ‘one of the most beautiful examples of double attack ever conceived on the chessboard’.

The starting-point in all three books was the position after 1 Qe3 Rxd6.

About Howard S. Hoit information is sought beyond what appeared on page 200 of the October 1942 Chess Review:

Above all, can the full score of Hoit’s brilliancy be found?

(9559)

We regret to learn from Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA) that he will probably be forced to cut back drastically his publishing plans:

‘I am getting more discouraged all the time, and am coming round to the view that what the chess world really deserves is a lot more openings books by Batsford. Hooper and I could have written ten trashy books on some opening or other in the time we took to do The Unknown Capablanca and might have made some money as well. Well ... live and learn.’

(1008)

The above was written in 1985. Subsequently, Dr Brandreth nonetheless published a series of excellent books on chess history, under the imprint Caissa Editions.

Colin McGuigan (Newtownards, Northern Ireland) sends a couple of extracts from the first two issues of Etero Scacco Problemi, printed in Italian and ‘English’:

It want be a push to the search of unexplored possibility of the chess board and its inhabitantes; a creative push; an incentive to rediscover the Chess as only play and not as science.

So, in every issue there are original articles but also pages of “pure madness of chess”.

We hope that E.S.P. be a push for greater “chess crazy”. (A thousand apologies for the judicious!).’

The question of correct language is not just one of vague aesthetic importance; what counts is whether precise thoughts are precisely phrased. To take another example, New in Chess continues to publish in its English edition sentences whose meaning is far from obvious. Occasionally too, insufficient knowledge of the language leads to unnecessary complications and embarrassment. In the July 1985 issue the Editor-in-Chief, Jan Timman, appears to misunderstand (in the context of the Moscow doings of February 1985) the actual meaning of the word ‘termination’.

Nevertheless New in Chess is already established as one of the best general interest magazines, and one can only hope that its excellent production standards won’t lead to cash-flow difficulties. Its coverage of top master tournaments is particularly fine, even if sometimes a single event is allowed to swamp an entire issue. The practical difficulties of producing parallel Dutch and English editions cannot be underestimated, which makes the lively editorial team’s achievement so far all the more remarkable.

(1036)

One of the most interesting aspects of New in Chess is the detailed interviews that have appeared in recent numbers [in 1985], e.g. Spassky (June), Kasparov (July), Schmid (August) and Timman (September). However the most memorable was a moving, though badly written, article by Mischa de Vreede, who has paid several visits to Jan Hein Donner, the victim of a stroke two years ago and now confined to a nursing home. The article/interview, in the August New in Chess, is a desperately sad report on a wonderful personality.

(1056)

The issue of Donner’s forename(s) was discussed in C.N.s 8299, 8304 and 8312.

From Ed Tassinari (Scarsdale, NY, USA):

‘In New in Chess (April 1985) Tim Krabbé in “Record Inventory” cites among the longest games an arranged draw (Rogoff-Williams, Stockholm, 1969, 221 moves). Yet, writing in the Australian Chess Championship Yearbook 1971-1972, R. Jamieson, in an article on the 1971 World Junior Championship, Athens, mentions a 224-move game ending in stalemate in the final round between Rosenberg (Scotland) and Haigh (Wales). Was this another bogus game à la Rogoff v Williams? Interesting also that both games took place in the World Junior Championship event.’

Incidentally, on the same page (53) of New in Chess, the famous ultra-short game Combe-Hasenfuss is given. However, according to R.N. Coles – who was there – the opening was 1 c4 c5 2 d4. Source: BCM 1973, page 44.)

(1064)

A letter to Robert B. Long, the Editor of the Chess Gazette, which, of course, was not published:

Geneva, 2 July 1985

Dear Mr Long,

I was intrigued by your remark in issue 37 of the Chess Gazette that it now seems to you that Chess Notes is ‘being written by the same three people in the guise of collective genius’.

In fact, the latest number (22) publishes contributions from David Hooper, Brian Reilly, Warren Goldman, Anthony Saidy, John Nunn, Ken Whyld, John Roycroft, Hugh Myers, Leonard Barden, Bernard Cafferty, Paul Buswell, Dale Brandreth and G.H. Diggle.

Which three did you have in mind?

Yours sincerely,

Edward Winter

(1074)

A discrepancy which is not of momentous importance, but which readers may be able to clear up swiftly, concerns the size of Mikhail Chigorin. Most sources suggest that he was little short of a giant, but on page 22 of Chess Characters G.H. Diggle reports that at Hastings, 1895 W.H. Watts ‘had expected Chigorin to be a great burly Russian, but found him in fact a small jerky man, no bigger than Steinitz ...’ Is there a photograph which puts the matter beyond doubt?

(1106)

An endnote on page 269 of Chess Explorations:

On page 29 of his first volume of best games, Tartakower called Chigorin ‘the Russian giant’, not necesarily a reference to physical size.

From J.H. Duke (Melbourne, Australia):

‘In the second issue of Lasker & His Contemporaries there is a photograph of the participants in the Cambridge Springs tournament of 1904 in front of the Rider Hotel. Chigorin, standing in the front row, certainly appears to be a small man. The giant of the field is Marco, who towers over everyone else.’

Who has been the tallest master? The late J.H. Donner would be a popular nomination, but on pages 10-11 of the October 1955 issue of CHESS there is a photograph in which he is standing alongside a distinctly taller Filip.

(1878)

The description of Pillsbury in C.N. 3141 as a short man prompts us to quote a brief item entitled ‘The Height of Players’ from Sunday States, as given on page 500 of the American Chess Magazine, June 1899:

‘Are chessplayers tall men? Generally speaking, we should say not. If the average height of masters were to be ascertained it would be below five feet seven inches. Considering the stature of the past and present masters, we think the average would be about five feet six inches. Paul Morphy was a small man, and we are told that as he sat before Meek in their game of the American tournament they were referred to as David and Goliath. Meek remarked that if Morphy didn’t give him a chance he would put the little fellow in his pocket. Harrwitz was a little man; Paulsen was not large; Zukertort was small; Steinitz is very short; Pillsbury, Lasker, Weiss, Tarrasch, Walbrodt, Charousek are all little men; Gunsberg, Mason, Schlechter are far from large. Of the tall players Blackburne, Chigorin, Showalter, Mackenzie, Pollock, Burn, Marco, Schiffers, Maróczy are of the minority.’

C.N. 1106 quoted W.H. Watts’ description of Chigorin as ‘a small jerky man’. See pages 192-193 of Chess Explorations. In an article on Hastings, 1895 in Saturday Review, 31 August 1895 (see pages 359-362 of Jacques N. Pope’s monograph) Pillsbury called Walbrodt ‘a very small man also, the smallest of all the competitors’.

Pillsbury’s remark is confirmed by other descriptions and photographs, with one exception: in the Dresden, 1892 photograph on page 56 of A Picture History of Chess by F. Wilson the player identified as Walbrodt appears taller even than Blackburne.

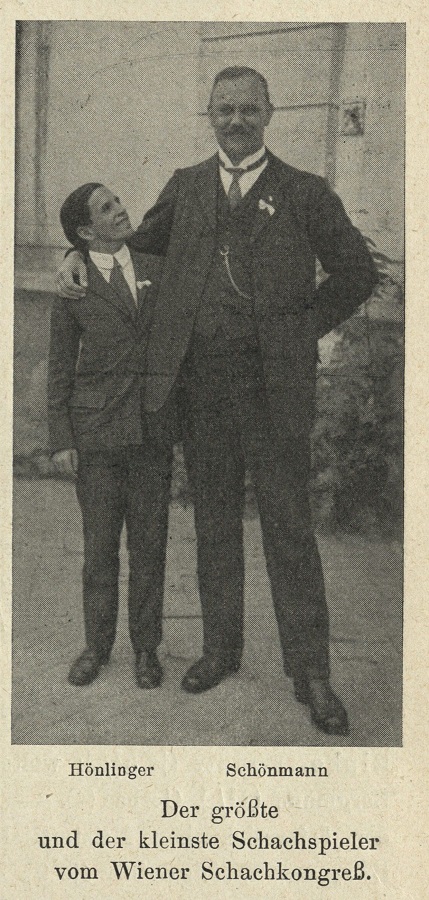

Below, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, is a photograph of B. Hönlinger and W. Schönmann taken at the Congress of the German Chess Union in Vienna in 1926, from page 227 of the August 1926 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

(3146)

One of the tallest of the older masters was Paul Lipke. From page 34 of the October 1894 Chess Monthly:

‘Socially, Herr Lipke is of pleasing, gentlemanly manners; good-looking …; head and shoulders above the average amateur at chess, and also in height, he measures 195 centimetres in his stockings.’

The magazine stated, moreover, that Lipke was ‘one of the best living blindfold players’ and had given exhibitions on eight and ten boards.

(3171)

An addition to our list of tall chessplayers is Willem Jan Muhring. Stefan Muellenbruck (Trier, Germany) quotes from page 98 of Meesterlijk geschut by W.J. Muhring and J. Roelfs (Amsterdam, 1955):

‘Muhring is precies 1.98 m lang en derhalve een indrukwekkende figuur.’

(3185)

The following quote comes from an article by Hans Kmoch and Fred Reinfeld on pages 9-11 of the January 1951 Chess Review:

‘… Tarrasch was given short shrift by Mijnheer te Kolsté of Holland in the Baden-Baden tournament held in 1925. Te Kolsté had turned up as a rather inadequate substitute for Dr Max Euwe. Approximately seven feet tall, weighing 250 pounds and with hands the size of a chessboard, te Kolsté presented a formidable appearance. His accomplishments were by no means so formidable, and te Kolsté represented little more than a bye in the tournament. For example, during his game with te Kolsté, Tartakower spent most of the time chatting with Alekhine, and, at one point, seeing that te Kolsté had made a move, Tartakower interrupted the conversation with the remark: “Excuse me, I have to see whether my opponent has left his queen en prise.” And, sure enough, he had done just that.’

Whether Jan Willem te Kolsté (1874-1936) was really about 2.13 metres tall we are unable to say, but the well-known group photograph taken at Baden-Baden, 1925 does not give that impression. As regards the Tartakower game, it may be thought that a more likely, and less derisive, comment would be (after 16…Qe7), ‘Excuse me, I have to see whether my opponent has left his queen to be trapped’.

(3308)

See too our feature articles on Max Euwe and William William, as well as the Factfinder references to Carl Walbrodt.

At Budapest, 1926 Alekhine’s Defence was played 15 times, and the Queen’s Indian Defence 24, much more than any other openings in the tournament. Why? (For example, there were six French Defences, one Caro-Kann and nine Sicilians, so Alekhine’s Defence all but outnumbered the other semi-open defences combined.)

(1135)

As recorded on page 27 of Dale Brandreth’s edition of the Kemeri-Riga, 1939 tournament book, the Ruy López was played in that event only once in the 120 games. It will be surprising if a reader can quote a comparable case concerning this most popular of openings.

(1607)

As mentioned on page 260 of Chess Explorations, C.N. 593 quoted Fine’s observation in Lessons from My Games (page 152) concerning AVRO, 1938: ‘It is curious that not a single player dared to try a Sicilian in the whole tournament.’

Ken Whyld (Caistor, England) writes:

‘Soviet Chess by R. Wade. A few years ago in casual conversation with Wade I asked him how much embarrassment had been caused to him by the printer jumbling up what he had written about Boleslavsky and Bondarevsky and putting them under one heading (page 171) “Isaac Bondarevsky”. He looked startled and said, “None”. I could only conclude that the book had not had the volume of sales it surely merits, otherwise surely someone must have picked it up.’

(1148)

Another pair sometimes confused are Chajes and Jaffe; both were born in Russia but became active in US circles around the second decade of this century. Even so, it was rather much for Miguel Sánchez (page 239 of volume II of Capablanca, Leyenda y Realidad) to write about ‘Chaffes’.

In the circumstances, it is surprising that Kasparov and Karpov are not muddled more often. One jumble appeared on page 16 of the Daily Telegraph of 20 September 1986, where B.H. Wood reported on game 18 of the third K-K match under the headline ‘Lost chance bodes ill for Karpov’:

‘The 18th game of the world chess championship match in Leningrad was adjourned last night in an obscure position where Gary Kasparov has what advantage there is.

If Anatoly Karpov loses, it will be a double tragedy for him, for he turned down an opportunity to draw by perpetual check. After that, he lost a little ground.’

It was Kasparov, not Karpov, who could have forced the draw. And it would have been a draw by repetition of position, not perpetuai check. Karpov eventually won the game.

(1546)

Mate in one move

Solution: There needs to be a white square in the bottom right-hand corner. Turning the board 90 degrees in one direction allows 1 Kd4 mate and, in the other, 1 fxg8(N) mate.

This problem by Alapin was published on page 88 of the March-April 1916 Wiener Schachzeitung, together with two easier mate-in-one positions (based respectively on the familiar tricks of the en passant rule and nine black pawns).

(1158 & 1195)

A footnote on page 3 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

A problem by W. Langstaff in which White has nine moves and mates in one after the removal of any one of them was given on page 554 of The Social Chess Quarterly, July 1935.

The ‘Christmas Puzzle’ hereunder, by J.C.J. Wainwright, appeared on page 262 of the December 1917 American Chess Bulletin:

‘White mates in one move’

The solution was given on page 50 of the February 1918 issue. It must be Black’s move; whatever he plays, White then mates in one move.

(Kings, Commoners and Knaves, page 3)

The first paragraph of C.N. 1160:

Chess Openings – Your Choice! by Stewart Reuben (Oxford, 1985) is one of the most peculiarly written books we have seen, no mean accolade. On the whole it merits a welcome for the practical assistance it offers the relatively weak player, and it is undoubtedly a work into which the author has put much. Nonetheless, we would be hard put to quote any other title which has so much wisdom and fatuity side by side. Just as one is admiring his presentation, S.R. suddenly goes berserk for a sentence or paragraph before the book resumes its normal respectable course.

Many examples were then given, the first being from pages 4-5, where Reuben offered for consideration ‘an alternative definition’ of the opening: ‘The opening is the stage of the game where at least one of the two players has seen the actual position on the board before.’ [For further details see Book Notes.]

Below is a later item (C.N. 1650), which considered Reuben as a chess magazine columnist:

C.N. 1160 illustrated how Mr Stewart Reuben’s judgements are often erratic. Further proof of this is provided by his new series of ‘Viewpoint’ articles in the BCM. The June 1988 issue has an especially memorable example (elegantly entitled ‘Who Dun It?’).

‘The editor has asked me to write on the subject of collaborations in chess writing. Well, you can understand why he shirked the topic, can’t you? Who wants to be the subject of a libel suit or to be shunned by ones [sic] peers?’

Eyewash, because the BCM editor would in any case have to assume responsibility for a contributor’s libel, but at least the illogicality of this jaunty introduction serves to distract attention from the ‘ones’ and, for that matter, from the equally erudite ‘each others’ which graces the following paragraph.

The BCM’s star stylist informs us, with regard to his book Chess Openings – Your Choice!, that ‘... it took George Botterill to point out a glaring fault in an innovation I recommend. That was in his review of the book in the New Statesman. Now, that is what I call a review in depth!’ Now, that is what we call useful information: no identification of the blunder to enable readers to write a pencil correction in their copies.

Next on the bill is a shallow reference to Euwe’s literary collaborations, notable only for Mr Reuben’s ignorance of the entire subject (including, of course, Lodewijk Prins’ authoritative observations in C.N. 1529). The following is Mr Reuben’s full contribution: ‘Many of Dr Euwe’s works are thought to be primarily the work of his collaborators. However, one doubts such an honourable gentleman failed to give the material at least a cursory glance.’

The next stunning revelation from the BCM’s colourful columnist: ‘An English writer complained to me recently of the number of errors in a book he was reading for the first time. It did not seem to occur to him that having his name on the dust-jacket as a co-author carried the responsibility of at least reading the book in proof form.’ It is unlikely that many will have been electrified by this further phut of non-facts, limply justified in the very last paragraph of the article: ‘You will be disappointed that I have allowed certain practices to remain shrouded in anonymity but David Anderton (BCM’s lawyer) wouldn’t have allowed more frank confessions anyway.’