Edward Winter

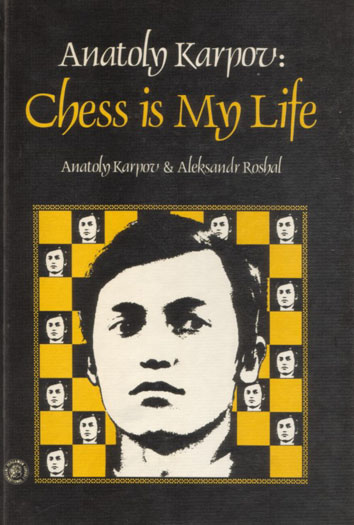

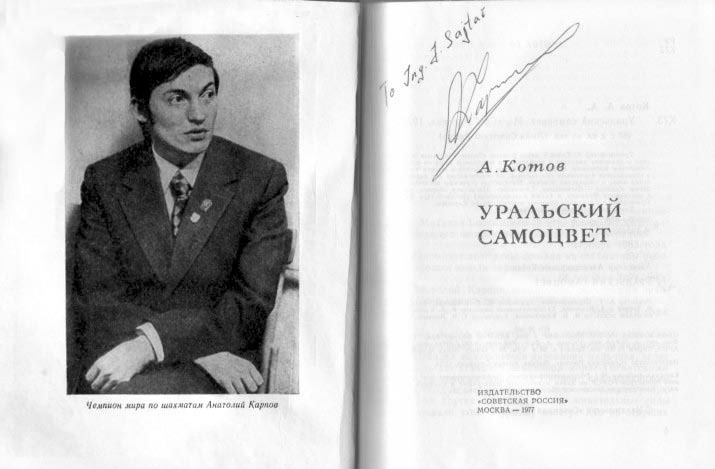

Although his peak years should, incredibly, still lie ahead, Anatoly Karpov has already achieved as world champion a chain of successes unmatched by any other post-war titleholder. In terms of both quantity and quality of play his record is simply without parallel. For an account of his career to date (or, rather, as far as the preparations for the 1978 Korchnoi match) he has collaborated with the journalist Aleksandr Roshal to produce a remarkable work comprising no fewer than 359 large pages. A detailed biographical narrative is interspersed with over 100 games, almost a third of them finely annotated by Karpov himself.

A big book with a twee title, it amounts to one prolonged standing ovation for the great Soviet player, with Roshal clearly out to prove himself a reincarnation of Morphy’s biographer and spaniel F.M. Edge. The idealized portrayal is even aided by the photographs, an offbeat collection in which Karpov dutifully conveys to the camera his talent for fishing, boating, playing billiards, appreciating art, feeding a horse and collecting stamps. (Not all in the same snap, it should be pointed out, although Roshal’s fawning prose suggests that Karpov might well cope even with that.) Roshal certainly has the words to match: ‘In his collection there are now tens of thousands of specimens, and about each stamp he knows literally everything.’

In the circumstances it is strange to find the Izvestiya chess correspondent complaining that ‘the apology for a critic does not accept the existence of half-tints and paints portraits of top grandmasters in one colour only’. Good words but having identified the trap, Roshal falls headlong into it. His brushwork – many many would say daubing – on Korchnoi is decidedly monochrome, which is in stark contrast to the rosiness abounding in the acclamation of ‘Tolya’ or, to quote one chapter heading, ‘the flying man from the Urals’. Here the shrill hosannas are enough to raise Philidor, and in the end it is left to Karpov himself to make the occasional murmur of self-criticism that proves vital for the book to retain some semblance of perspective, not to say dignity.

The tricky question that arises is whether Soviet writers should be expected to restrain their enthusiasm for Karpov if the West is, rightly, also rhapsodizing over him. At what point does well-meaning patriotism tip over into short-sighted chauvinism? Britain’s recent advance in the game is already being labelled an ‘explosion’ although such hyperbole might have been better left until the emergence of one or two British world champions. For all its naivety and worse, Russian chess ‘propaganda’ is at least firmly based on staggering achievements over the decades. Roshal’s principal weakness is not so much that he is a propagandist but that, less bearable still, he is a bad propagandist. He will put many readers off Karpov for life.

There are disappointingly few revelations about the subject’s private life, inner thoughts or even training and study routines. The public persona is presented as a cool-headed, rather self-willed individual with few illusions about his immense powers. ‘I always want to be first. If I weren’t a chessplayer, all the same I would aim to be first at something.’ In a 1976 interview with foreign journalists he was asked, inevitably, to name his most dangerous rivals. Now on such occasions protocol demands a good-natured platitude or two in reply along the lines of ‘I consider that Master X is a player to watch, and I always enjoy our vigorous battles’, but instead Karpov rejoindered coldly, ‘I don’t see anyone at the moment’. Roshal is right to note that his great compatriot demonstrates ‘not an unhealthy vanity, but a conscious pride’, although he neglects to add that one of the real keys to Karpov, as well as to Fischer for that matter, is ruthlessly objective logic. It may not always win friends, but is a quality that lies at the very heart of both players’ approach to chess and, indeed, to life in general.

Hardly any attempt is made to analyse why Karpov is so good at chess, except through a quagmire of quotations like ‘In general one has to learn not to lose, and wins will then come of their own accord’. The rather unsatisfactory conclusion at the end of the 359 large pages is simply that Karpov is an ‘enigma’. Name a world champion who wasn’t.

The Pergamon edition reads well, despite intermittent lapses into shaky English including, if we may quibble, an annoying determination to on every possible occasion split infinitives. But neither translator nor reader is given an easy time by such sentences as: ‘He was the guest of engineering workers and river transport workers, machine operators and vegetable growers, corn-producers and fishermen, geologists and volcanists, students and young pioneers’ (page 248). The absence of a general index is lamentable, there being no rule that, just because Soviet literature is rarely well indexed, translators may not make amends themselves. The footnotes, however, are most apposite. Fewer and the reader would have been left bewildered; more and the text would have been undermined.

For the student of Karpov (and who can afford not to study him?) the book certainly presents a mass of information, though much of it is awkwardly selected and organized, and does offer a genuine insight into the strains of life on the grandmaster circuit, as well as some idea of the additional burden resting on the world champion. It becomes evident that many strong players would happily finish a tournament bottom with one solitary point if only that ignominious score could result from a victory over Karpov. Every opponent is a resolute scalp-hunter.

The co-authors provide many unexpected touches of wit and intriguing examples of razor-sharp observation: ‘Polugayevsky plays excellently in positions which demand exact and concrete calculation, but loses his way in positions where there is no specific plan.’ ‘When the competition becomes more fierce, Larsen’s nerves will simply not stand it.’ ‘Andersson plays as if he were an old man, who knows everything and fears everything.’ When Fischer decided to spectate at San Antonio, 1972, he flew in just in time for the final round, and Roshal observes wryly, ‘He had acquired a new habit – now he was late not only for his own games, but also for other people’s’. Yet elsewhere judgements can be bland beyond belief. Here is Karpov’s recollection of his first contact with Fischer, at the same San Antonio tournament: ‘All I can say is that outwardly he made on me personally a favourable enough impression.’ End of reminiscence.

Both the strengths and the weaknesses of journalism are represented in Chess is My Life, with flashes of lively and informed writing standing alongside material that is superficial and scrappy. It is a pity that there is so much chaff amongst the wheat. At half the length this would have been twice the book.

***

This book review was first published on pages 444-446 of the October 1981 BCM.

A more extensive quote from page 59 of the book:

‘Sacrifice a piece? Why not sacrifice if, of course, it is correct. Only I do not intend to burn my boats, as some do – burning boats is not my speciality ...

Regarding draws, I normally go along simply to play chess, without thinking beforehand in terms of a draw. Half-points suit me if I do not get the sort of game I want, or if these half-points enable me to attain a desired result in the event. In general one has to learn not to lose, and wins will then come of their own accord.’

From earlier on the same page:

‘I am asked why it is that I play quickly (can it be, they say, that I am never in doubt as to what to play?), and why my games frequently end in draws ... The rapidity of my play is not at all, as some think, due to the fact that everything is clear to me. Simply I don’t wish to get into time trouble. So far this has happened to me two or three times in my life, and I realize that sometimes it is better to restrict oneself simply to a good move and not seek the very strongest, rather than suffer the dissatisfaction of defeat.’

Addition on 30 October 2020:

Concerning the second paragraph, in view of all the information that has come to light since 1981 (see, for instance, Edge, Morphy and Staunton), ‘spaniel’ can no longer be considered an appropriate word to describe Edge vis-à-vis Morphy.

Very few calendar dates have entered chess lore, despite possible prompting at the time. Page 59 of Anatoly Karpov: Chess is My Life by A. Karpov and A. Roshal (Oxford, 1980) has this piece of old-style second-hand reportage:

‘When Botvinnik heard by telephone that Karpov had become one of the winners of the Alekhine Memorial, he exclaimed, according to the person who informed him: “Remember this day, 18 December 1971. A new chess star of the first magnitude has risen.”’

(12170)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.