Edward Winter

The present article complements:

***

The recent rumpus over Kasparov’s participation in the Candidates’ competition has proved once again that few of us have a clear idea how FIDE works, still less a good understanding of the background to major chess fixtures. About the only book to make a serious attempt at removing the lid and revealing – fairly – the brew is Chess Scandals: The 1978 World Chess Championship by E.B. Edmondson and M. Tal (Pergamon, 1981).

Some jottings:

Quote by Karpov after a colourless draw in 18 moves in the first match-game: ‘We were only testing the equipment.’

‘Game five established two records in world championship play. It was the longest ever (game 14 of Tal-Botvinnik 1961 lasted for 121 moves) and the first one to end in a stalemate.’

Quote by Petra Leeuwerik (who Edmondson believes was unwittingly a hindrance to Korchnoi’s cause): ‘Viktor must really be going mad; now he doesn’t even realize that he is being disturbed.’

Quote by Karpov to the arbiters: ‘I’ll stop swiveling if he takes off his glasses.’

Korchnoi when he closed the score from 5-2 to 5-3: ‘Well, I have now won one game in a row.’

The late Colonel provides a mass of documentation, tracing all the unbecoming disputes that marked the 1978 match as one of the most bitter in the game’s history. It seems strange that the 1972 Spassky-Fischer match did not give rise to such a book (we are discounting the scurrilous fiction of Brad Darrach).

Inevitably our knowledge of behind-the-scenes ‘scandals’ varies enormously from one world championship match to another; try researching the Capablanca-Alekhine encounter of 1927 and you will be lucky if you can even find a single photograph of the players.

(509)

Nowadays Karpov gives almost as many interviews as he plays games, and has learned to perfection the requisite skills. The Edmondson book mentioned in C.N. 509 [Chess Scandals] gives a three-page transcript of a press conference in Baguio City. To the assembled newshounds Karpov showed himself to be charming, unassuming, discreet, reasonable and diplomatic in best Sebastian Coe fashion. None of the above adjectives is particularly appropriate for Korchnoi, who acts more like a human being, relishing his new-found freedom of speech.

(540)

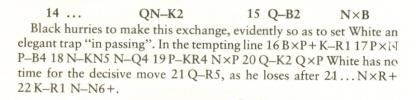

In a match which decided the world championship a master proved ignorant of an elementary rule of the game. ‘Every schoolboy knows’ that the fact that a rook is attacked does not prevent castling with that piece, yet in the Candidates’ Final of 1974, Korchnoi v Karpov, the former – by his own admission – was uncertain. With regard to the position that arose after Black’s 17th move in the 21st match-game, Korchnoi writes on page 161 of Chess is my Life (London, 1977):

(795)

See our feature articles on Victor Korchnoi and Castling.

A major controversy in Harry Golombek’s journalistic career:

‘Harry Golombek suspects a sinister plot behind the disastrous performance of the challenger in the world championship’

Golombek strongly criticized the performance of both players, and the key (speculative) passage was:

‘Perhaps Kasparov has been warned not to play well and has been given to understand that the consequences for him and his family would be disastrous if he did.’

‘What my critics fail to explain is why Kasparov is playing in a style totally unprecedented for him in which he embarks on attacks without due preparation – a procedure which he has never before adopted. They also fail to explain why he is adopting lines of play and openings which are fimiliar [sic] to Karpov and not at all the type of opening he himself has played before.’

There was also this paragraph:

‘Mr Golombek pointed out yesterday that the results to date were entirely out of keeping with the normally accurate Elo rating system of classifying the strength of champions. The most recent assessments of Karpov and Kasparov had indicated a match win by the challanger [sic] of about six games to four, he added.’

A letter to The Times from [‘Señor’] Campomanes was also cited:

‘Any suggestion that either player is being driven by external pressures into consciously substandard play is absured [sic] and ridiculous. The reality is that Karpov, the world champion, is producing chess of a very high standard, and his challenger, Kasparov, though less a [sic] successful hitherto, has fought and give [sic] of his best.’

The final paragraph added that Golombek’s arguments had also been rejected by members of Kasparov’s delegation.

For Kasparov’s comments on the controversy, see pages 115-116 of ‘Garry Kasparov on Modern Chess Part Two Kasparov vs Karpov 1975-1985 including the 1st and 2nd matches’ (London, 2008).

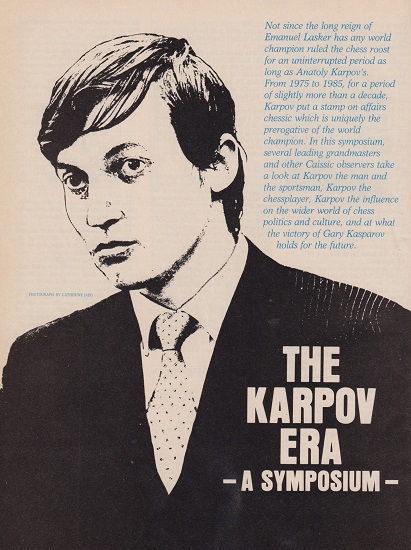

In C.N. 1143 we quoted from a Symposium on ‘The Karpov Era’ on pages 26-34 of the March 1986 Chess Life. For example, although Arnold Denker observed regarding Karpov, ‘even his severest critics never questioned his right to reign’, four pages later Charles Pashayan wrote:

‘... is it really any wonder that the World Chess Champion Bobby Fischer remains aloof from public chess?’

And here is Lev Alburt:

‘Isn’t it time that we Americans recognize the truth: Bobby Fischer is the reigning world champion.’

He called Kasparov ‘the new FIDE world champion’.

(9880)

A remark by Larry Evans about Karpov on page 30 of the March 1986 Chess Life:

‘He will go down in history as the man who avoided a match with Bobby Fischer and then eluded him for the next ten years.’

This needs to be compared with what he wrote at the time Karpov became champion. From Chess Life & Review, November 1975, page 760:

‘Fischer refused to negotiate or compromise and his stubbornness is what killed the match – nothing or nobody else. Despite “mathematical proof” that his conditions were fairer than the old system, they were still not fair. “Fair” means no advantage to either side. All the words in the world can’t obscure that simple fact.’

And in the December 1975 issue, page 813:

‘Fischer was the best player. Seclusion has made him an unknown quantity. Karpov deserves to be world champion, and the burden is now on Fischer to prove otherwise.’

After quoting a tribute by Kasparov to Fischer, Evans comments in the March 1986 Chess Life that ‘this generous spirit was alien to Karpov’. Incredible. Karpov too has praised Fischer’s role in popularizing chess (e.g. in Chess Life, March 1983, page 11) and even observed in My Best Games, page 10, that ‘Fischer has been underestimated for a long time, in my opinion’.

(1143)

Endnote on page 266 of Chess Explorations:

In C.N. 1176 Ken Neat (Durham, England) criticized the English translation of Karpov’s My Best Games and suggested that a more reliable version of what Karpov said about Fischer was to be found on page 194 of Anatoly Karpov: Chess is My Life (Oxford, 1980).

On page 44 of the August 1986 Chess Life, Larry Evans writes:

‘To set the record straight, some readers wondered how I could criticize both Fischer’s silly title conditions (10 wins, but the champion keeps his title in case of a 9-9 tie) and Karpov’s refusal to accept those demands (see CL, March 1986, page 30). What I actually wrote about Karpov was that “he will go down in history as the man who avoided a match with Bobby Fischer and then eluded him for the next ten years”. Whether GM Karpov was right or wrong, I believe that posterity will remember him mainly for ducking Fischer – just as we remember Howard Staunton for ducking Morphy. Not once after assuming the crown did Karpov make a conciliatory gesture to lure Fischer back to chess. And, perhaps, such will be Karpov’s epitaph.

History, after all, is a harsh mistress.’

Mr Evans, we fear, is tying himself up in knots. He believes Karpov was right not to accept Fischer’s 1975 conditions but also that Karpov will be remembered for avoiding that match. And although in 1975 Mr Evans was saying that Fischer’s ‘stubbornness is what killed the match’, and although on that very page 44 of the August 1986 Chess Life he states with reference to Fischer, ‘you cannot force someone to do something against his will’, he nonetheless criticizes Karpov for failing to make a conciliatory gesture. And because (according to Mr Evans) Karpov failed to make a conciliatory gesture, that proves that Karpov ducked Fischer.

Between 1866 and 1884 (though beyond that date too) Steinitz was generally considered to be the strongest active player in the world. During that period did he make any attempt to entice the retired Morphy back into chess? We must hope to goodness that he did, or else Larry Evans will next be on the warpath against Steinitz, the man who ducked Morphy.

(1192)

C.N. 1457 pointed out that on page 10 of The Chess Beat (Oxford, 1982) Larry Evans expressed the opposite view: ‘It looks like Fischer has been ducking Karpov, not the other way around.’ (The column had appeared on, for instance, page 16 of the Reno Evening Gazette, 10 February 1979.) As noted in Chess Journalism and Ethics Larry Evans wrote in January 1988: ‘FIDE drove two Americans Reuben Fine and Bobby Fischer out of chess.’

On page 348 of the June 1979 Chess Life & Review Evans wrote: ‘Up to now Bobby has been ducking Anatoly, not the other way around.’

In Chess Life, July 1991 (page 444) he tried to reconcile his various statements by claiming that Fischer and Karpov had ducked each other:

‘Who ducked whom? This has been asked many times; they both share the blame – and so does FIDE.

... Since Fischer’s demands were the only obstacle to their match, in that sense he certainly ducked Karpov. Yet nobody knows if Fischer would have played even if he got all of his demands!

That said, Karpov ducked Fischer by refusing to play under conditions mathematically more favorable than those offered to any FIDE challenger.’

***

To summarize, Larry Evans has written:

- ‘It looks like Fischer has been ducking Karpov, not the other way around.’ (1979).

- ‘Bobby has been ducking Anatoly, not the other way around.’ (1979).

- ‘Posterity will remember [Karpov] mainly for ducking Fischer.’ (1986).

- ‘[Fischer] certainly ducked Karpov.’ (1991).

- ‘Karpov ducked Fischer.’ (1991).

***

Another one from Evans:

Reno Gazette-Journal, 18 April 1987, page 33

(12127)

See also The Facts about Larry Evans.

The opening sentence of a report by Raymond Keene on page 2 of The Times of 21 December 1987 claimed that Kasparov is ‘the first player in more than 75 years to come from behind to win the world chess championship’.

What about the title matches played in 1927, 1935, 1937, 1951, 1954, 1957, 1963, 1969, 1972 and 1985?

(1582)

An item in Cuttings:

From page 46 of the 3/1993 New in Chess (interview with Anatoly Karpov):

‘You may ask any grandmaster who knows Keene. Everything he is involved in is based on personal interests.’

On page 44 of From Baguio to Merano by A. Karpov and V. Baturinsky (Oxford, 1986) Karpov referred to Raymond Keene’s ‘sharply unpleasant traits’.

On his chessgames.com page (a post dated 17 April 2019) Raymond Keene could not be bothered, following Tony Buzan’s death, to look up a Karpov v Buzan game which he himself had published in the Sunday Times (‘Maybe a search in ST archives wd locate it’).

The game-score was given by Raymond Keene in his Sunday Times column on page 53 of the Supplement, 15 December 1996. After asserting that the Immortal Game between Anderssen and Kieseritsky [sic] was played at Simpson’s in the Strand, for which there is no proof, the column stated (without any further information such as the precise date or occasion) that at Simpson’s in 1995 Anatoly Karpov (‘the World Chess Federation champion’) won the following game against Tony Buzan (‘a well-known author on the brain’): 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 b6 4 Nc3 Bb7 5 a3 h6 6 d5 Be7 7 e4 exd5 8 cxd5 d6 9 Bb5+ c6 10 dxc6 Bxc6 11 Bxc6+ Nxc6 12 O-O O-O 13 Bf4 Qd7 14 Rc1 Rfd8 15 Nd5 Nxe4 16 Rxc6 Resigns.

In an interview in the November 1988 Revista Internacional de Ajedrez Karpov discussed (pages 13-14) his legal confrontation with a former West German journalist, Helmut Jungwirth, over the latter’s alleged embezzlement of computer advertising returns. On 1 December 1988 various European newspapers reported that Karpov had won his case and that the journalist had been committed to prison.

(1767)

Below are two interesting paragraphs from Kasparov’s Foreword to Elie Agur’s book Bobby Fischer: A Study of His Approach to Chess (London, 1992):

‘When I compare my own career with that of Fischer, I have to admit that I enjoyed a certain advantage over him. He had no-one besides himself to draw him up to the heights he reached, whereas I have been privileged in having a high-class player like Karpov, who forced me to exert myself and advance ever higher.

If one may judge a player’s strength by comparing him with his contemporaries, it seems to me that Fischer’s achievement is unsurpassed – the gap between him and his closest rivals was the widest there ever was between a World Champion and the other top-ranking players of his time. He was some 10-15 years ahead of his time in his preparation and understanding. This could be attributed in part to his dedication to the game, which was unequalled by any other player before or since.’

(2328)

From pages 161-162 of Karpov on Karpov (New York, 1991), during a description of the mid-1970s discussions between Fischer and Karpov on a possible world championship match:

‘After the talks we set out for a stroll around Tokyo. I was afraid that autograph hounds would harass us, but, to my amazement, not one person approached us. Here were two of the best chessplayers in modern times, whose photographs practically never left the front page, walking down the street – you’d think at least someone would have noticed. Later I understood that such a thing is possible in only one place on earth: Tokyo.

One photograph – the only one in which Fischer and I are together – was taken. The chairman of the Japanese Chess Federation, Matsumoto, ingratiated himself with Fischer, who disliked journalists even more than their articles, and took our picture “for his family album”. A few days later the shot was sold to Agence France-Presse, who in turn distributed it worldwide.’

Somehow that photograph seems to have passed us by. Can any readers say where it has been published?

(3588)

Given Karpov’s statement that a photograph of Fischer and him in Tokyo in the 1970s was distributed worldwide by the Agence France-Presse, it is strange that no reader has yet informed us where it may be seen.

(3627)

The Karpov-Fischer photograph remains to be found, but Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) has sent us a picture of a badge which appears to have been produced specifically for their expected match. He reports that it is 4cm high by 3.7cm wide and is made of metal and enamel.

(3635)

In the passage below, originally published in the May 1982 Newsflash, G.H. Diggle describes a simultaneous exhibition by Anatoly Karpov at Westergate School, England on 13 April 1982. For the full article, see page 82 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984).

‘The world champion in action is probably the quietest and most impassive since Morphy. He presents a huge contrast to Alekhine, who would “launch a foaming tide of White pieces” against 25 victims, striding from board to board as though he had “a tiger in his tank”, and pawing the ground impatiently to get at fresh prey. Anatoly Karpov, “lithe rather than muscular”, wanders delicately around the boards and daintily moves the pieces as though arranging flowers (where possible, he always slides a piece rather than lifts it). At the end of the first three hours (sadly, the BM had to miss the rest) all 25 boards were still in action without a result. The champion, as fresh and imperturbable as at the start, gave no facial indication as to how he thought matters were going, but remained sphinxlike “in trouble and in joy”. He had one occasional mannerism – on pausing at a board he would thrust his left forearm across his front and press his left hand under his right armpit, a slightly Napoleonic touch. In one respect (the BM was informed) he broke with “simul” tradition. The BM (to his own vainglorious delight) had been accorded a seat in the Press Gallery (i.e. the front row) and found himself sitting next to an old comrade in arms, T.W. Sweby of the Luton News. For a brief space they were joined by the BCM Games Editor [William Hartston], who gazed at the world champion’s perambulations as though slightly mystified, and then assumed a grave expression. Perceiving that he was about to give sotto voce utterance, T.W.S. and the BM eagerly craned their necks so as not to miss one word of “IM” wisdom. “Do you realize”, whispered W.R.H., “he’s rotating anti-clockwise.”’

(5317)

Koyalovich – Karpov

St Petersburg, 1903

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 d5 4 Bxd5 Qh4+ 5 Kf1 g5 6 g3 fxg3 7 Kg2 Bd6 8 e5 Bxe5 9 Qe1 Qd4 10 Bxf7+ Kxf7 11 Nf3 Bh3+ 12 Kxh3 g4+ 13 Kg2 gxf3+ 14 Kxf3 Nh6 15 hxg3 Qd5+ 16 Kf2 Ng4+ 17 Ke2 Qe4+ 18 White resigns.

This game was published on page 182 of L. Bachmann’s Schachjahrbuch für 1903, three pages after the well-known blindfold encounter Pillsbury v Kasparovich, Moscow, 14 December 1902.

(Kingpin, 1996)

Another game by Karpov the Elder:

Karpov – Sigfried

St Petersburg, 11 September 1906

Giuoco Piano, Møller Attack

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 5 d4 exd4 6 cxd4 Bb4+ 7 Nc3 Nxe4 8 O-O Bxc3 9 d5 Bf6 10 Re1 Ne7 11 Rxe4 O-O 12 d6 cxd6 13 Ng5 h6 14 Nxf7 Rxf7 15 Bxf7+ Kxf7 16 Qh5+ Kf8 17 Bxh6 Qe8 18 Bxg7+ Bxg7 19 Rf4+ Nf5 20 Rxf5+ Ke7 21 Re1+ Resigns.

Source: Časopis českých šachistů, 1906-07, page 75.

(Kingpin, 1997)

Here is a third specimen, taken from page 249 of the July 1939 issue of Schackvärlden:

Karpov – Mitin

Irkutsk, 1939

Queen’s Pawn Game

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 e3 g6 4 c4 Bg7 5 Nc3 c6 6 Qb3 O-O 7 Bd2 b6 8 Bd3 Bb7 9 O-O Nbd7 10 cxd5 cxd5 11 Rac1 e5 12 dxe5 Nc5

13 exf6 Nxb3 14 fxg7 Nxc1 15 gxf8(Q)+ Qxf8 16 Rxc1 Rc8 17 Rd1 a6 18 a3 b5 19 Ne2 Qd6 20 Bc3 Qb6 21 Bd4 Qa5 22 Ne5 Qa4 23 Rf1 h5 24 h4 b4 25 axb4 Qxb4 26 f4 Qd2 27 Nc3 Qxb2 28 Rb1 Qd2 29 Rxb7 Rxc3 30 Rb8+ Kh7

31 Nc4 Qe1+ 32 Bf1 g5 33 f5 f6 34 Bxf6 Resigns.

(2827)

From Clive James and Chess:

A paragraph from Clive James’ television column in The Observer, 11 October 1981, page 48:

‘Why have there been so few important female chessplayers? Arguments about social repression have never satisfactorily answered the question. The Freudian view, summed up in a classic paper by Ernest Jones, is that the game represents a man’s oedipal attempt to kill his father, but a simpler view would suggest that women just aren’t nuts enough. The World Chess Championships (BBC-2) are a case, or perhaps two cases, in point. Korchnoi is fairly obviously some sort of weirdo. We have not forgotten the poisoned yoghurt [sic] and the enemy thought-waves. But Karpov, if you look closely, is even weirder. With Korchnoi some of the obsessiveness remains unfocused and spills out in the form of dingbat behaviour, as it did with Bobby Fischer. But with Karpov it is all beamed straight at the chess-board. Get between him and it and you’ll fry.’

Two further references to Karpov by Clive James:

‘Where Karpov is King (BBC-2) showed the strength of Soviet chess, personified by Anatoly Karpov, a hard-eyed mastermind whose Krypton Factor is plainly right off the scale.’

Source: The Observer (Review section), 13 November 1977, page 31.

In a review of the Rose Bowl on Grandstand (BBC-1):

‘The complexity of the game was matched by the complexity of its television coverage. Cameras were everywhere. The commentary was deeply informed and highly statistical. “John, this reminds me of the fake punt Stanford ran in 1957 ...” Or it could have been 1857: my notes are a scrawl. Action replays and freeze frames helped demonstrate that every flurry of action was an intricate plan either working itself out or else being countered with similar intricacy. The whole affair, appealing as it did with equal force to the aggressive instincts and the intellect, rated with the Karpov-Miles chess final in Master Game (BBC-2) as an answer to the pressing demand for a moral equivalent of war.’

Source: The Observer (Review section), 15 January 1978, page 31.

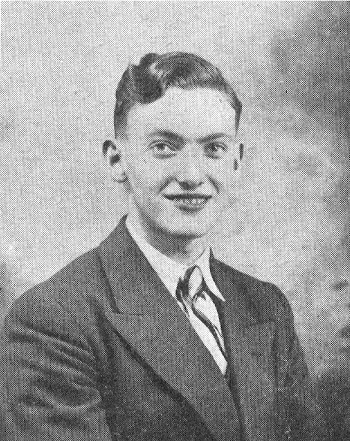

In C.N. 858 [written in 1984] we suggested that that there was a striking physical resemblance between Abe Yanofsky (in a photograph published on page 1 of the October 1942 CHESS) and Anatoly Karpov. A subsequent item (C.N. 1070) quoted the view of B.H. Wood (Sutton Coldfield, England):

‘Frankly I don’t detect the least resemblance to Karpov. Of course I’ve met both perhaps 100 times’.

Here is the Yanofsky photograph, so that readers can decide for themselves:

(Kingpin, 2001)

A quote commonly attributed to Anatoly Karpov is given, to pick a book at random, on page 45 of Kasparov v Deeper Blue by Daniel King (London, 1997):

‘Karpov, the blue-eyed Russian who once stated that the two great loves of his life were “chess and Marxism” ...’

We have seen the original quote ascribed to Der Spiegel of 3 June 1985 and shall be grateful if a reader can provide a copy. In the meantime, two later comments by Karpov come to mind:

‘On dit souvent de lui qu’il a deux passions: “Les échecs et le marxisme”. “C’est une vision simpliste”, rétorque-t-il, “j’ai aussi d’autres intérêts culturels. De plus, je suis président du Fonds soviétique en faveur de la paix.” Une fonction à laquelle il tient particulièrement, ajoute-t-il.’

Source: Le Journal de Genève, 1-2 February 1986, page 25.

‘– You’ve been quoted as saying you have two loves – chess and Communism.’

‘– I never said this. That was a provocation invented by the people who prepared the press information. I have many loves – my wife, my family, my son. I play tennis, I collect stamps. I like the theater.’

Source: interview given by Karpov to Anne Underwood, Newsweek, 3 December 1990, page 58.

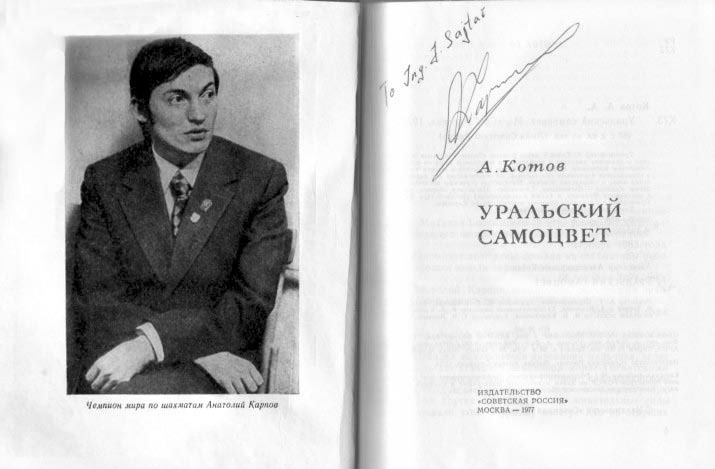

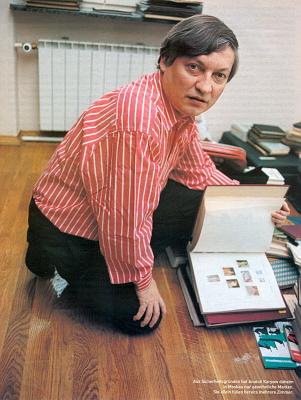

The above photograph accompanied an article about Karpov and his stamp collection on pages 42-50 of Das Magazin, 8-14 May 1999. It stated that he owned over a million items.

(6301)

Andreas Saremba (Brieselang, Germany) reports that the article containing the alleged Karpov remark can be read on-line (Der Spiegel, 3 June 1985). The passage in question:

‘Karpow hingegen ist Russe. Er ist ZK-Mitglied des Komsomol, Präsident des sowjetischen Friedensfonds und Träger des Leninordens. Seit seine Ehe geschieden wurde, bewohnt er eine Villa 40 Kilometer vor Moskau allein, meist umgeben von Freunden. Er fährt einen Mercedes mit Autotelephon. “Ich habe nur zwei Lieben, Schach und Marxismus”, ist ein für ihn typischer Satz.’

(6324)

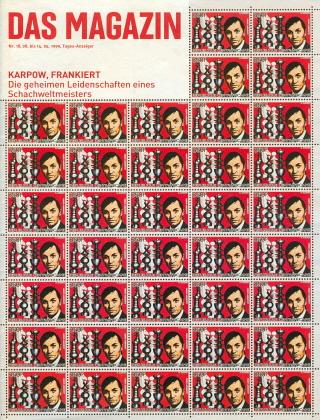

The front cover of Das Magazin was shown in C.N. 5489:

Das Magazin (Zurich), 8-14 May 1999

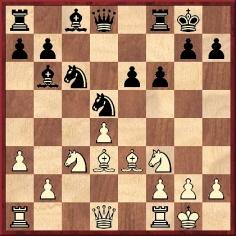

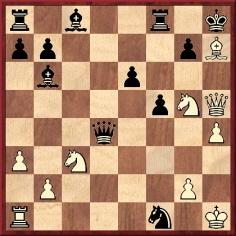

Alan O’Brien (Mitcham, England) notes that on page 2 of Anatoly Karpov His road to the World Championship by M. Botvinnik (Oxford, 1978) a mate in one was missed in the notes to the first match game between Polugayevsky and Karpov, Moscow, 1974:

Position after 22 Kh1 (analysis by Botvinnik)

Rather than 22...Ng3+ Black has 22...Qg1 mate. We see that the error was already on page 17 of the Russian edition, Tri Matcha Anatolia Karpova (Moscow, 1975).

(5669)

In C.N. 1243 (see page 161 of Chess Explorations) W.D. Rubinstein drew attention to a booklet published in Madras in the mid-1980s, Karpov’s Best Games by V. Ravi Kumar (or Ravikumar). From the author’s introduction, entitled ‘Karpov “The Man Machine”’, a few sentences (to use that noun loosely) were quoted:

‘He was awarded the Chess Oscar for his outstanding achievements in Chess. A honour which he won many times in succession Karpov is a Solid Positional Master but if the situation warrants he can glar himself to a tactical Genious. In the chapters that follows of his selected Games from 1980 to 1984 are annotated with my own notes for your entertainment.’

Also regarding the introduction, it remains to be discovered on what grounds the author attributed this remark to Botvinnik:

‘Anatoly Karpov is unquestionably the strongest chess player of the century.’

(7790)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) draws attention to an impressive series of articles by Lim Kok Ann on the 1978 world championship match.

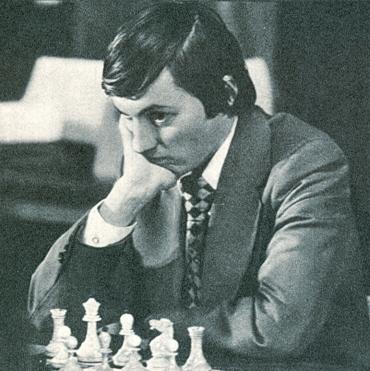

From the front cover of the match

book Het schaak der wrake

by H. Bouwmeester, J. van den Herik and L. Jongsma

(Utrecht/Antwerp, 1978)

(8177)

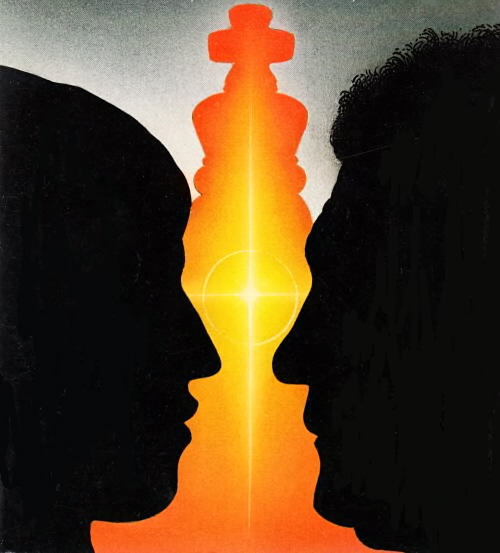

Also in Chess Silhouettes is the following:

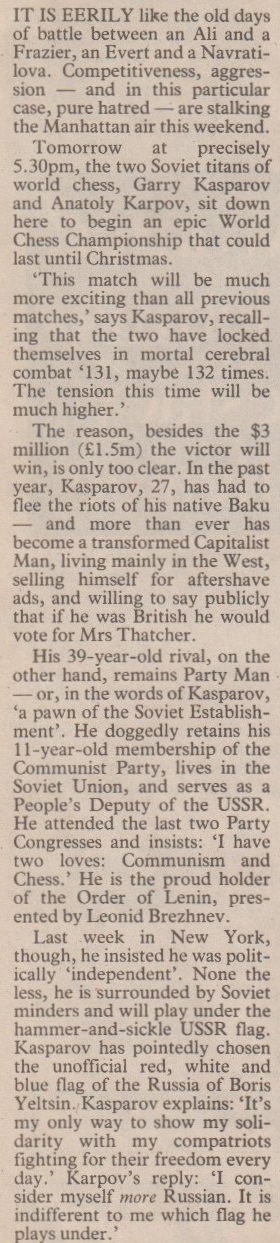

A silhouette of Kasparov and Karpov was often published in connection with their 1990 world championship match. Below, for instance, is the heading to an article ‘Pure hatred as Capitalist King meets Party Pawn’ by Andrew Stephen on page 13 of the Observer, 7 October 1990 (C.N. 9345):

C.N. 13 (see page 232 of Chess Explorations) cited a quip by Petrosian during the 1974 Karpov v Korchnoi match, from page 166 of Anatoly Karpov: Chess is My Life by A. Karpov and A. Roshal (Oxford, 1980):

‘The press centre was linked to the stage by four television screens. Arranged in groups around the chessboards, grandmasters and journalists analysed the position, periodically glancing at the screens. At the start of the match (before his departure to the international tournament in Manila) perhaps the most popular figure in the press centre was Petrosian. The journalists would constantly turn to the ex-world champion: “Tigran Vartanovich, what should be played here?” “When I knew that, I was down on the stage, instead of up here”, was Petrosian’s joking reply.’

(8410)

A 1982 cartoon (cutting only) from an unidentified Soviet newspaper:

(8785)

An addition to Chess as Front-Page News is shown below, from our archives: the Journal de Genève of 2 September 1997.

The report, by Mikhaïl Wadimovich Ramseier, affirmed that a FIDE/PCA reunification contest between Kasparov and Karpov (‘the match of the century’) was likely to take place in the Théâtre impérial de Compiègne, France from 20/21 October to 25 November 1997. The organizer was named as Carol Stroë, the president of a village chess club (Le Plessis-Belleville), and he claimed to be putting forward prizes of ten million French francs for the winner and five million for the loser. There would be no sponsorship for the 22-game match. Funding would come from selling the pictures to 43 television companies for $80,000 each, and from audiences in the 780-seat theatre (200 French francs per ticket).

Following a statement from Kasparov’s representative, Owen Williams, a report on page 10 of the Journal de Genève, 6 September 1997 made it clear that the whole thing was off or, better say, had never been on.

(9062)

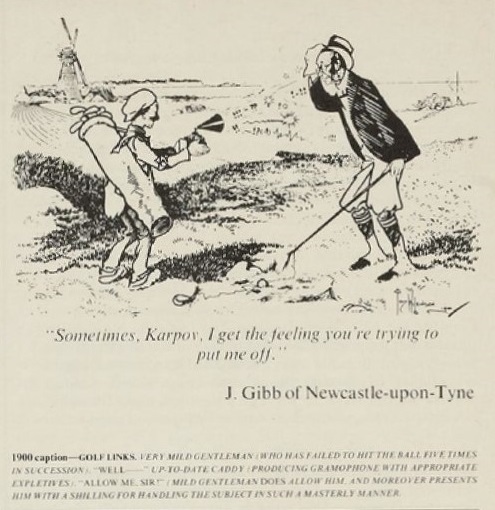

Punch, 16-22 August 1978, page 66.

(9124)

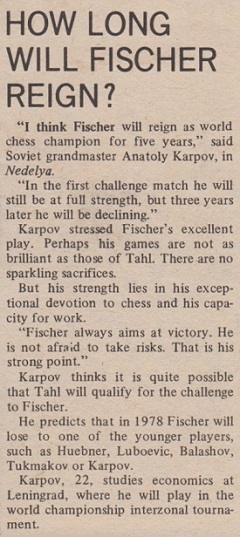

From page 15 of Soviet Weekly, 2 June 1973:

(9142)

Below is the first section of an article ‘Pure hatred as Capitalist King meets Party Pawn’ by Andrew Stephen on page 13 of the Observer, 7 October 1990:

There were many similar articles in the 1980s and 1990s. They left no doubt as to the writer’s sympathies, though plenty as to his credentials. Little or nothing is sourced, and the reader cannot know where the information comes from, or judge how trustworthy it is. A single article such as Andrew Stephen’s could provide fodder for a dozen C.N. items soliciting corroboration of the various quotes and assertions.

As regards the rivalry (‘pure hatred’) between Kasparov and Karpov, to what extent have journalists been duped? A remark from page 213 of Karpov on Karpov (New York, 1991), a book referred to in Karpov’s Writings, is worth recalling:

‘Every match is preceded by scandalous situations. Some arise spontaneously, others are planned, but in general a match never comes off without them. Kasparov and I also tried to uphold the ancient tradition and toss the journalists some choice morsels.’

(9345)

A ‘secret’ match between Spassky and Karpov, was mentioned by the latter in an interview with Irwin Fisk posted by ChessBase on 2 March 2015:

‘I.F.: Spassky was in preparation to play Fischer for the world championship. Had you played Spassky?

A.K.: Yes, I played a training match with Spassky. He asked me to play training games, but we played only one game. Spassky won this game even though he had a lost position, but I made a stupid mistake, and after this suddenly Spassky said he didn’t want to continue this training match, so maybe he was happy he beat me in that game.

I.F.: Where was this game played?

A.K.: We were near Moscow.’

A similar, though more detailed, account is on pages 98-99 of Karpov on Karpov (New York, 1990):

‘Toward the end of the camp, Spassky, wishing to check his form, decided to play several games with me. In the first game, he selected the Ruy López. I played White and quickly gained a winning position. All I had to do was hold on to it for a little while longer, but, weary from the previous inactivity and irritated by how I was being treated, I decided to show off and embarked upon unnecessary tactical complexities. This gave Spassky a chance to display his customary resourcefulness. I should have regrouped in time, changed the arrangement, and played to at least hold on to what remained. But I already realized my lead was receding, and I overplayed and lost. Spassky liked this game. He decided that his form was superior and there was no reason to continue checking it. My participation in his final prematch training was virtually limited to this one game.’

On page 8 of the September 1989 Chess Life A. Soltis disseminated a different version:

‘In some instances, no details about a match are ever disclosed. Or a smidgen of information surfaces, such as after the 1972 world championship match, when Anatoly Karpov confirmed the rumors that he had played a match to help prepare Boris Spassky for the challenge of Bobby Fischer. All Karpov would say then about the result was “I did not lose”.’

A similar text appeared on page 148 of Soltis’s book Karl Marx Plays Chess (New York, 1991), but in neither case did he offer the reader any source. It is possible that he was relying on a mere rumour published, as an editorial end-note, on page 70 of the February 1973 Chess Life & Review:

(9361)

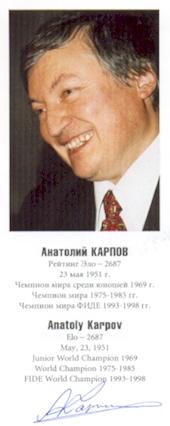

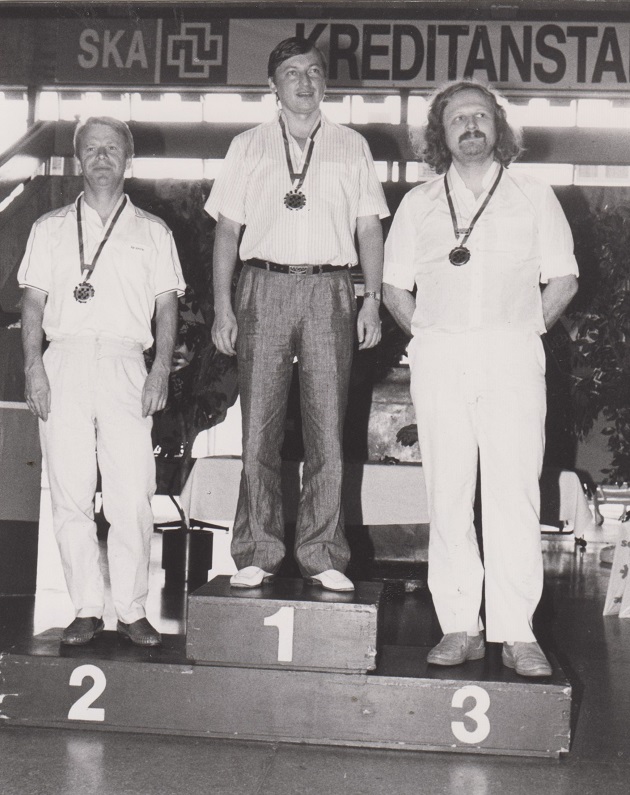

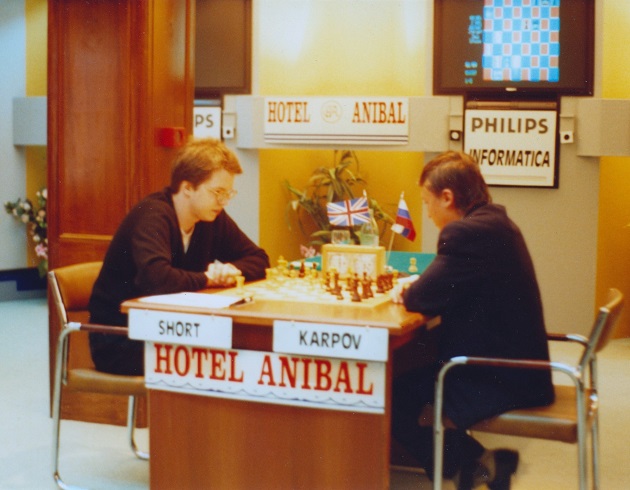

These photographs from our collection were given in, respectively, C.N.s 9363, 9455, 9517 and 9997:

Playing against Yasser Seirawan

With Ulf Andersson and Tony Miles (Biel, 1990)

Linares, 1992

Another Everyman book (one of several, alas) whose bibliography raises questions about the author’s research and, even, about his interest in the subject is Karpov move by move by Sam Collins (London, 2015):

Our feature article lists some 40 books about Karpov. Collins’ bibliography (page 5) mentions one.

(9485)

As quoted in C.N. 1322, pages 73-74 of From Baguio to Merano by A. Karpov and V. Baturinsky (Oxford, 1986) had these remarks by Karpov:

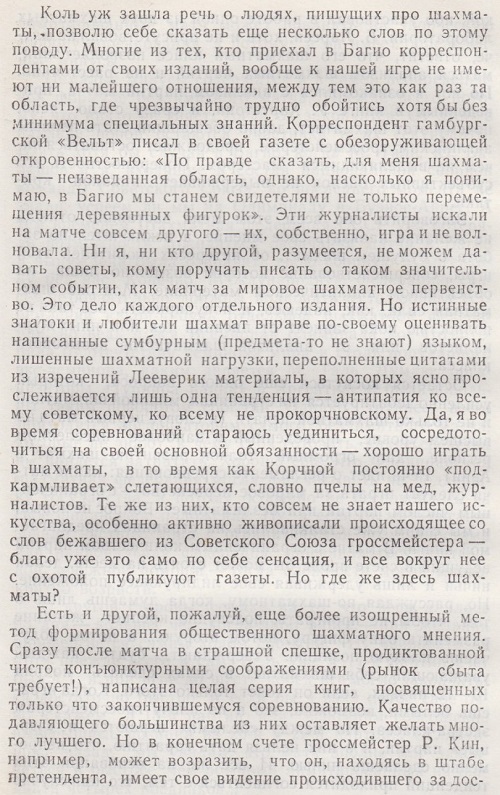

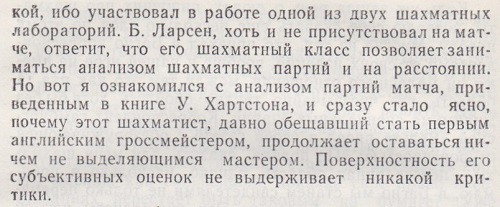

‘Since the question has arisen about people writing on chess, I will permit myself to say a few words regarding this. Many of those who came to Baguio as correspondents for their papers had altogether not the slightest connection with our game, and in fact this is one field where it is extremely difficult to get by without a minimum of special knowledge. The correspondent of the Hamburg Welt wrote in his newspaper with disarming honesty: “To tell the truth, for me chess is an unknown sphere, but, as I understand it, in Baguio we are witnessing not only the moving of wooden pieces.” These journalists were seeking something quite different at the match – as a matter of fact, the play did not concern them. It stands to reason that neither I nor anyone else can advise who should be entrusted with writing about such a significant event as a match for the world chess championship. This is a matter for each individual publication. But genuine chess connoisseurs and enthusiasts have the right to judge as they will material written in obscure (because they do not know the subject) language, lacking in chess content, and full of citations from pronouncements by Leeuwerik, in which only one tendency is apparent – antipathy to everything Soviet, to everything which is not pro-Korchnoi. Yes, during competitions I endeavour to withdraw into myself, and to concentrate on my main duty – which is to play well at chess, whereas Korchnoi constantly “feeds” the journalists, swarming like bees round a honey-pot. And those of them who altogether had no knowledge of our game described in especially vivid terms any pronouncements by the grandmaster who had defected from the Soviet Union – since this in itself was a sensation, and everything associated with it was readily published by the papers. But where does chess come into all this?

There is another, perhaps even more refined, method of forming public chess opinion. Immediately after the match, in fearful haste dictated by purely opportunist considerations (the market demands it!) a whole series of books devoted to the match were written. The quality of the overwhelming majority of them leaves a great deal to [be] desired. But in the end, grandmaster Keene, for example, might retort that, being on the staff of the Challenger, he could see for himself what was happening on the board, since he participated in the work of one of the two chess laboratories. Bent Larsen, although he was not present at the match, would reply that his chess strength enables him to analyse chess games even at a distance. But then I made the acquaintance of an analysis of the match games in a book by William Hartston, and it immediately became clear why this player, who for a long time promised to become the first English grandmaster, continues to remain an ordinary master. The superficiality of his subjective comments is beneath all criticism.

What forced me to speak about all this was by no means a desire to express my opinion, but solely my concern for the future of chess, and for the interests of chess enthusiasts, who can improve their play only from objective analytical material. My chess strength and, I hope, my popularity, nevertheless do not yet depend completely on the description of this or that journalist, or on the analysis of low-class players.’

(9980)

The Russian book with Karpov’s observations was В далеком Багио (Moscow, 1981), and the passage in question is shown below, from pages 155-156:

(10001)

In our original item, C.N. 1323, written in 1987, we concluded with the following observation concerning the Pergamon edition:

One final note on this book (which, incidentally, is exceptionally well proof-read): it contains the allegation that Harry Golombek and Murray Chandler helped the Korchnoi camp by regularly analyzing adjourned games. Denying this in the BCM of December 1981 (page 513), Golombek expressed the hope that Karpov’s work would be translated and published in England ‘so that I can proceed to sue him for libel’. Now we shall see.

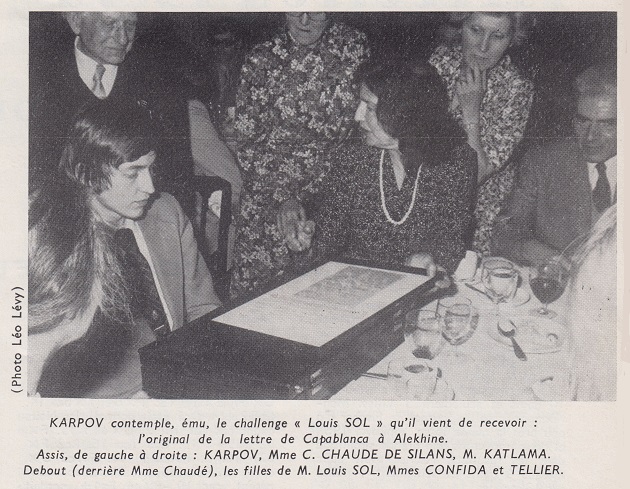

Concerning Capablanca’s letter to Alekhine dated 29 November 1927, which was shown in C.N. 10022, Thierry Lafargue (Mont de Marsan, France) draws attention to an article entitled ‘Le séjour de Karpov à Paris’ by Roland Lecomte on page 197 of Europe Echecs, July 1976. It recorded that at a reception in his honour in Paris on 2 June 1976 Karpov was presented with the original letter, which had been bequeathed to the Ligue de l’Ile-de-France by its late Honorary President, Louis Sol. The document ‘est destiné à être la possession du champion du Monde en titre’.

The relevant parts of the report:

Mr Lafargue asks where Capablanca’s letter is today.

(10050)

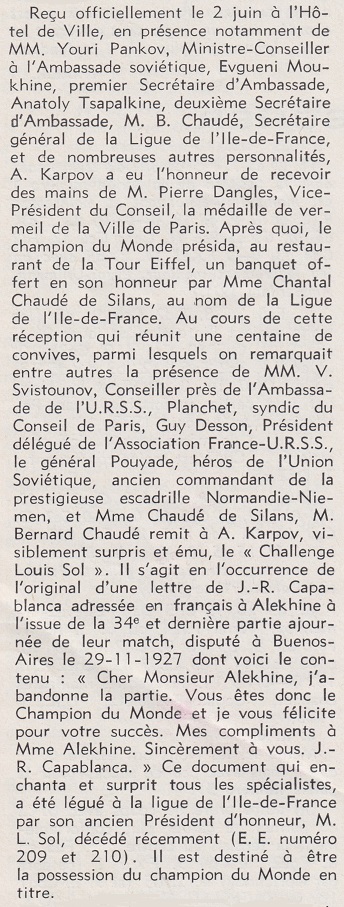

From page 16 of The Batsford Chess Yearbook by Kevin J. O’Connell (London, 1975):

‘Quote of the Year

“If you don’t believe in victory you have no business sitting down to a chess board.” Anatoly Karpov.’

No source was provided, but we give the following from page 3 of the January 1975 BCM:

Corroboration of the remarks in a Soviet source will be appreciated.

(10625)

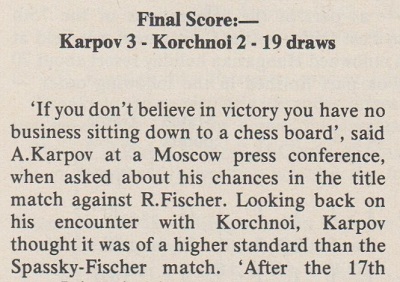

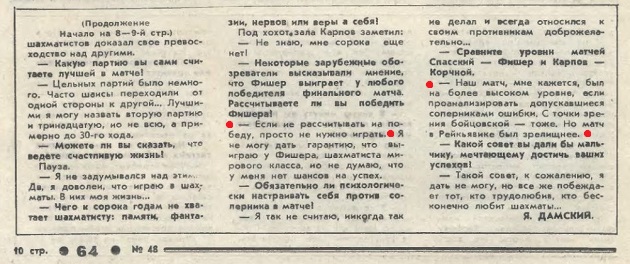

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) provides part of an interview with Karpov on page 10 of the 48/1974 issue (29 November-5 December) of 64:

Asked whether he expected to defeat Fischer, the future world champion replied: ‘Если не рассчитывать на победу, просто не нужно играть’. One of several possible translations is, ‘If you do not expect to win, you simply do not need to play’.

Our correspondent also notes Karpov’s view that, in terms of competitiveness and the number of mistakes, his match with Korchnoi was on a higher level than the Spassky-Fischer contest in Reykjavik, although the latter was more entertaining.

(10629)

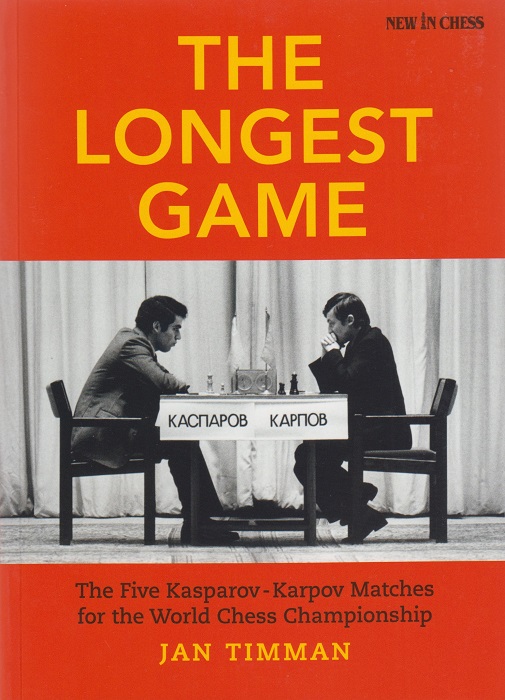

In the context of the 1986 world title match, on page 144 of The Longest Game by Jan Timman (Alkmaar, 2019) there is no mincing of words about Bjelica:

‘Karpov did not have a clear delegation leader, but he did have a press attaché: the Yugoslav Dmitri Bjelica. That was a strange choice, as Bjelica was known as a gutter journalist who wrote books that were full of printing errors and plagiarisms.’

(11226)

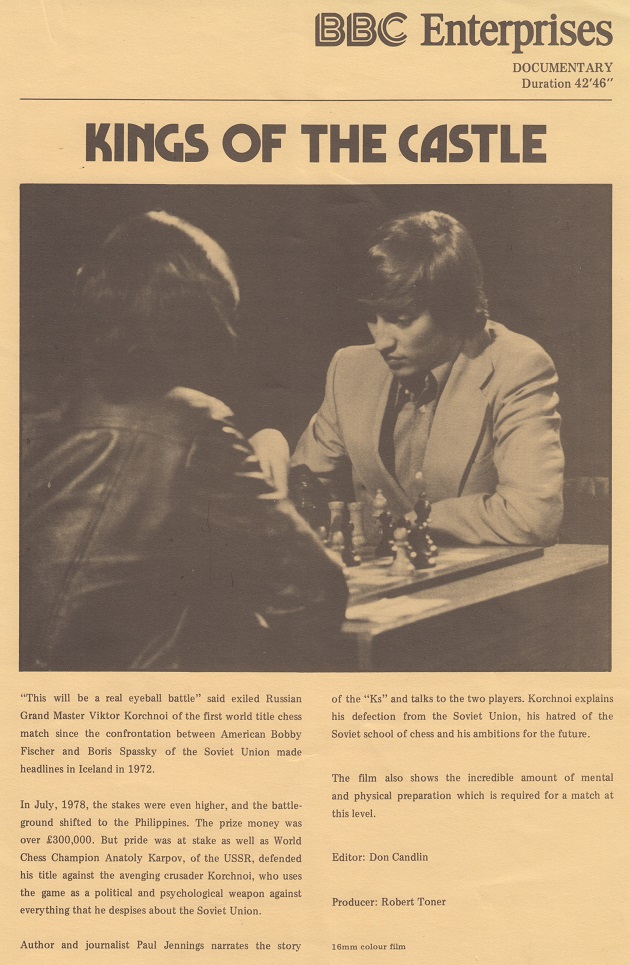

A programme not yet mentioned in Chess and Television is Kings of the Castle, narrated by Paul Jennings, produced by Robert Toner and broadcast on BBC-2 on 22 July 1978. We have this BBC Enterprises flyer:

Three years later, on 3 October 1981, a documentary of the same title was transmitted by BBC-2 ahead of the world championship match in Merano.

(11825)

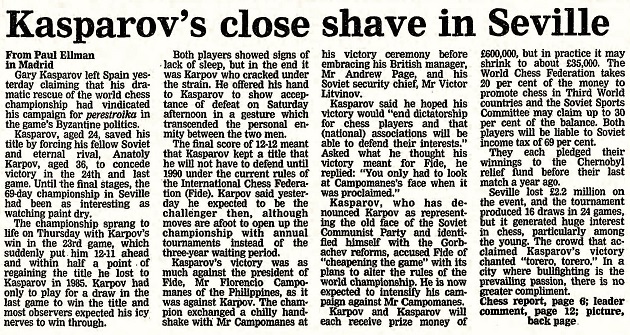

In addition to Leonard Barden’s detailed coverage of the final game of the Kasparov v Karpov title match in Seville on page 6 of the Guardian, 21 December 1987, the newspaper had this front-page report by Paul Ellman:

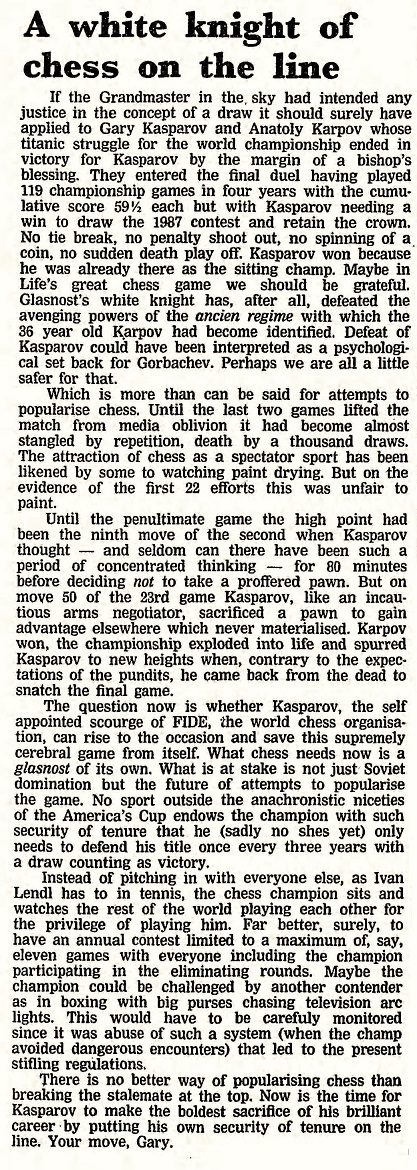

Page 12 of the same edition published an unsigned leading article:

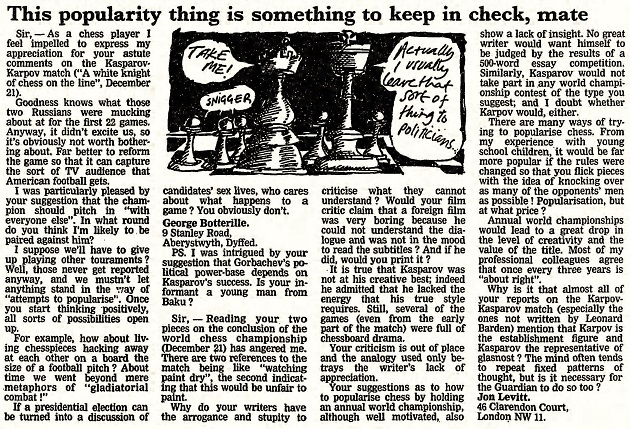

The items shown above prompted letters from George Botterill and Jon Levitt on page 8 of the Guardian, 24 December 1987:

Paul Ellman, the Guardian’s correspondent in Spain, died on 24 February 1988, aged 43. His obituary was on page 35 of the 26 February 1988 edition.

(11834)

Addition on 31 October 2024:

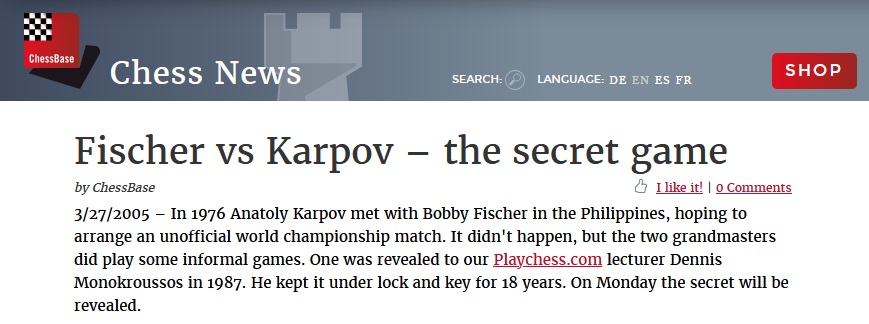

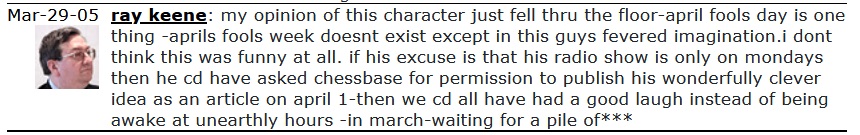

An obvious ChessBase hoax:

Who would fall for that?

From the chessgames.com page of Dennis Monokroussos:

In Cuttings we have commented: Guile and gullibility complacently co-exist.

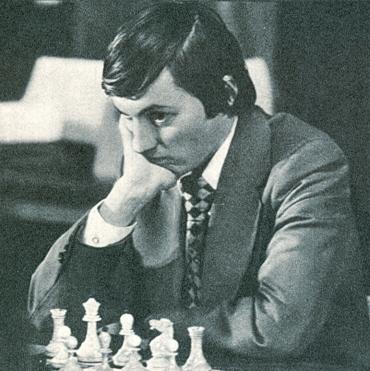

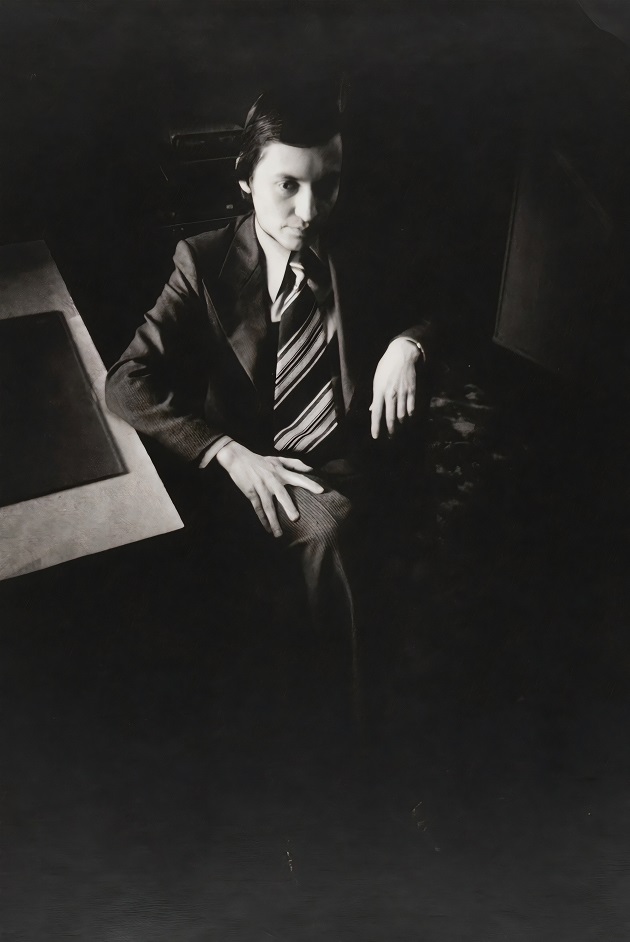

A 1970s portrait (courtesy of the State Russian Museum and Exhibition Centre Rosphoto):

(12143)

See too Articles about Anatoly Karpov.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.