Edward Winter

A miscellany of C.N. items about the great Estonian chess master.

The first paragraph of an interview with Capablanca in the Buenos Aires magazine El Gráfico:

‘Amongst the new talents there are two who stand out more as great masters than the others: Botvinnik and, on a secondary level, Keres. Also Alekhine, of course; but he is not new; he is old like me. Keres plays admirably well; his sense of fantasy is enormous, his imagination fiery. But his judgment is unsteady. He does not always know if the game in front of him is won, lost or drawn; and when it is won it also sometimes happens that he does not know for sure why and how it is won. Then, understandably, he hesitates and selects his plans more through temperament than through a judgment which has not managed to form. [Entonces, explicablemente, vacila y escoge sus planes más que por un juicio que no ha llegado a formarse, por temperamento.] However, it is a defect to substitute, at certain points in a game, judgment with instinctive impulses which rise up from temperament – aggressive impulses in the case of Keres, defensive ones in other players. In the highly instructive game we played in the Team Tournament which finished in this beautiful city a month ago, I offered him a draw because there was no way at all that it could be won, either by him or by me. Keres did not accept my offer then, and only did so six moves later. How was it that, six moves before, he had not seen with the same clarity as I that it was impossible to force the game? It cannot be believed that Keres would attempt to win against me in an absolutely drawn position, so the only explanation is that his reasoning had not yet crystallized into concrete judgment; to use the same word as before, he was hesitating. ... Against Eliskases, also in that tournament, Keres had to choose between accepting a draw in a perfectly balanced rook ending and trying to force matters with a peculiar king excursion. He picked the latter and lost. Why? Because in circumstances where visual foresight is not sufficient, where accurate judgment is necessary, Keres is still not fully developed.’

As cited in C.N. 863, Botvinnik commented on Keres as follows on page 109 of his book Half a Century of Chess (Oxford, 1984):

‘During the period from 1936 to 1975 he was probably the strongest tournament player.’

Some other comments, from page 110 of Botvinnik’s Achieving the Aim (Oxford 1981), were cited in C.N. 442, including the following:

‘As a player Keres had failings which were well known to me. The first was his slight uncertainty when he had to orientate himself in new opening schemes. He preferred on the whole obsolete opening systems. That was why he had a taste for open play. His second failing, a psychological one, was a tendency to fade somewhat at decisive moments in the struggle, while when his mood was spoiled he played below his capabilities.’

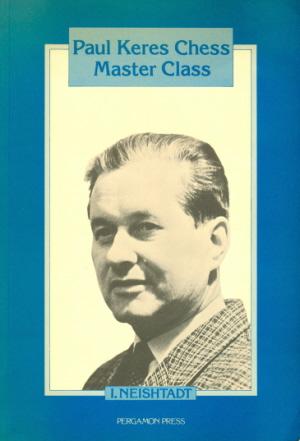

Pergamon Press continue to bring the best of contemporary Soviet literature to the English-speaking chess community with an absolute gem of a book, Paul Keres Chess Master Class by I. Neishtadt. All aspects of attack, defence, counter-attack – in short, the very meat of the game – are dealt with in eloquent detail, everything being based on examples from Keres’ actual play. Since the great Estonian possessed a style of play virtually unsurpassed in its fiery elegance, there could hardly be a better choice of model for the aspiring student. To gain maximum benefit the reader will have to work hard with this book (Neishtadt understands Keres’ play inside out), but it is certain that no budding enthusiast could fail to be inspired by both the games and the notes.

A truly excellent book. The English version (by Kenneth P. Neat, of course) runs most smoothly. Not to be missed.

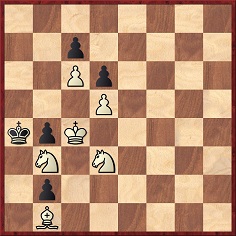

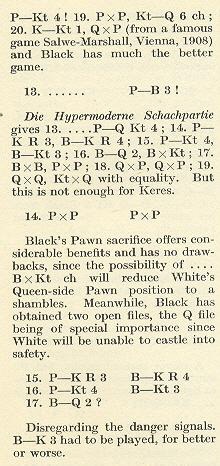

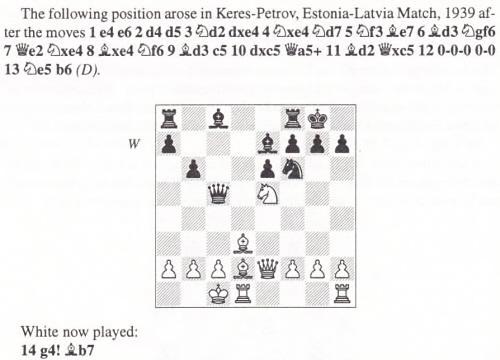

C.N. 626 also referred to this position:

Position after 22...Kd7-d6

The 23rd move of Keres v Alexandrescu, Munich, 1936 is given by the Neishtadt book as 23 Nc4+; other sources (e.g. Tartakower and du Mont) give 23 Ne4+.

Nobody has yet been able to clarify what Keres really played on his 23rd move against Alexandrescu, Munich, 1936. Two further contradictory sources. Page 20 of Olympische Blitzsiege by E.J. Diemer gives ‘Nc4+!!’, while the Ridal book of Keres’ games (of which we have the German and Swedish editions) gives ‘Ne4+!’

(1258)

We are grateful to Rob Verhoeven (The Hague, the Netherlands) and R.A. Hubbard (Bishops Stortford, England) for further (contradictory) evidence. 23 Ne4+ is given on page 12 of the August/September 1936 Eesti Male, page 276 of the 1936 Deutsche Schachzeitung and in the Wildhagen book of Keres’ games. But it was 23 Nc4+ according to page 88 of Schach-Olympia München 1936 and page 303 of the October 1936 Shakhmaty v SSSR.

(1275)

Paul Timson (Whalley, England) adds three more sources. Paul Keres 50 Parties (1916-1939) by J. Le Monnier and Meie Keres by Valter Heuer have 23 Ne4+, while T.D. Harding’s French: MacCutcheon and Advance Lines gives 23 Nc4+. [MacCutcheon should read McCutcheon.]

Our correspondent’s view is that ‘almost certainly Keres would have played the strongest and most decisive move, namely 23 Ne4+’. Mr Timson notes that there is so far a majority for Ne4+ in the sources quoted in C.N.

(1318)

From Ken Whyld (Caistor, England):

‘I believe Keres played 23 Ne4+. This is also given in the Wildhagen book, for which Keres supplied the material. Also, it leads to a forced mate, whereas 23 Nc4+ does not if Black plays e.g. 23...Kc5. After 23...dxc4 it is just as fatal as the other line, of course, viz. 24 Rfd1+ and mate in four at most.’

(1352)

The forced mated is 23 Ne4+ dxe4 24 Rfd1+ Bd4 25 Qxd4+ Ke7 26 Qg7+ Ke8 27 Bh5+ Qf7 28 Qxf7 mate.

From Carl-Eric Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden):

‘I am especially interested in the games of Paul Keres and would be very grateful for any help in finding more examples of his correspondence play. (He probably played about 500 postal games.) He wrote on page 15 of Ausgewählte Partien 1931-1958 that at one time he had 150 games running at the same time, and when he won the IFSB championship in 1935 he was involved in 70 games simultaneously.

The following game (Keres-E. Verbak, correspondence, 1932) was published in Fernschach number 2 in 1935: 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Be3 dxe4 4 Nd2 f5 5 f3 exf3 6 Ngxf3 Nf6 7 Bd3 c5 8 O-O cxd4 9 Nxd4 f4 10 Rxf4 e5 11 Bb5+ Kf7 12 Qh5+ g6 13 Bc4+:

Here Dr Dyckhoff’s booklet Fernschach-Kurzschlüsse and the book by Ludwig Steinkohl Faszination Fernschach give the continuation 13...Kg7 14 Qh6+! 1-0. “The final position deserves a diagram”, writes Mr Steinkohl.

However, Verbak actually played 13... Ke8 and resigned after 14 Qxe5+ Qe7 15 Qxf6 (Fernschach, which also mentions the variation 13...Kg7 14 Qh6+). According to Valter Heuer’s book on Keres, this game was played between September and October 1932, i.e. when Keres was 16. Heuer also gives the moves 15...Qxe3+ 16 Kh1 Qxd2 17 Re4+ Resigns.’

(936)

As reported in C.N. 978, in 1985 Mr Erlandsson sent us a two-page list of mistakes that he had noted in Faszination Fernschach.

From W.D. Rubinstein (Aberystwyth, Wales):

‘I would like to raise the question of Paul Keres’s wartime career and activities, which are surrounded by a good deal of mystery and controversy. Before posing the questions the chess historian would like to answer, some historical background must briefly be presented: Keres was an ethnic Estonian. Estonia was an independent democratic republic between 1918 and 1940. In June 1940, as a result of the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939, the Soviet Union invaded the Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, annexing them as Soviet “republics” with great brutality, including the deportation to Siberia of thousands of middle-class and anti-Communist Estonians. In June 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, taking over Estonia, with results vis-à-vis the local population too obvious to mention. (It should be noted that in the Nazi hierarchy of things, Estonians were virtual “Aryans”, like the Finns.) In September-October 1944 the Soviet Union recaptured and re-annexed Estonia, dealing with former collaborators and nationalists in a manner even more brutal than in 1940-41.

Paul Keres lived in Estonia and seemingly travelled freely throughout Europe in this whole period, participating in many chess tournaments, in a manner which seems virtually incredible. He participated in the USSR Championship of 1940 and the “Absolute” USSR Championship of 1941, then in a variety of Nazi-sponsored tournaments, such as Salzburg, 1942, as well as those in neutral European countries like Spain and Sweden. He was Champion of Estonia in 1942, 1943 and 1944-45, seemingly oblivious to the fact that Nazi rule had given way to Soviet rule. (The English translation of his autobiography, The Complete Games of Paul Keres, is of course silent on the political aspects of this.)

Perhaps the most vexing question concerns his reception back into Soviet-dominated Estonia in 1944-45. Normally Keres would have been regarded by the Soviet authorities as an traitor and Nazi collaborator, and would have been shot on sight. According to his biography in the Oxford Companion to Chess, “When the war in Europe ended he returned home, but not before making a deal with the Soviet authorities. He would be ‘forgiven’ for playing in German tournaments, i.e. collaborating with the enemy. In return Keres promised not to interfere with Botvinnik’s challenge to Alekhine.”

What is the evidence for this account? What is meant here by “interfere” and what power did Keres, a Soviet captive, have to “interfere” with anything? Presumably by this it is meant that Keres would not attempt to seek a championship match with Alekhine ahead of Botvinnik. But, again, did not the Soviet authorities have the absolute power to advance Botvinnik’s claim and thwart Keres’s, regardless? (This in turn raises another question which is extremely curious: why did not Keres play Alekhine for the championship in 1941-45 when they were the two strongest “Aryan” players – if Alekhine can be so described – (except for Euwe, in voluntary retirement) in Nazi-occupied Europe? Was there ever the possibility of such a match?) Did anyone act as a negotiator between Keres and the Soviets?

About 20 years ago in America I heard persistent rumours that as part of the price exacted by the Soviet authorities Keres was made to play badly against Botvinnik at the 1948 match-tournament. His play there was disappointing, but is this rumour likely to be true?

How did Keres get around Europe so readily with a World War on? What passport, for instance, did he travel on? Were any threats made by any regime against him or his relatives? Did he make any political statements à la Alekhine? Why did he return to the Soviet Union in 1945 (voluntarily, it appears, according to the Companion) rather than flee to the West? In part (though not, of course, wholly) because of his wartime record, Alekhine is regarded as a reprobate par excellence, while Keres is universally held to be one of the few authentic gentlemen of modern chess. Does this impression need revising, given that Keres’s wartime record seems identical to Alekhine’s (the disputed newspaper articles excepted)? Indeed, it seems much more opportunistic. Or should Keres be viewed as another innocent victim of the tragedy inflicted on Europe by the two great totalitarian regimes of the century? Is there any comprehensive and objective account of Keres’s activities during the decade of the 1940s – in the Baltic émigré press, for instance, or among Soviet refugees? Finally, has there not been what might fairly be described as a cover-up – or, at the very least, a fog of obscurity – around Keres’s life in this period, presumably to prevent difficulties from arising with the Soviet regime during Keres’s lifetime and to protect his very high reputation?’

(1454)

From Ken Whyld (Caistor, England):

‘The quote in the Companion was based on a conversation I had with Keres, over dinner, with no witnesses. He was congenial and informative in private. On a different occasion, in a different country, he was most formal with me. (There was a KGB agent nearby.) After the AVRO tournament at the end of 1938 he was the candidate for a title match, and Alekhine accepted the challenge (to be played not before the end of 1940, at the request of Keres). The war changed everything, but Keres could have gained overwhelming support for his claim to a match had he pressed. I did not ask Keres about his games against Botvinnik in the 1948 world championship, but my opinion is that Botvinnik had the edge over Keres, without any “fixing”.’

(1472)

As mentioned on page 268 of Chess Explorations, a detailed article by Valter Heuer appeared on pages 78-88 of the 4/1995 issue of New in Chess.

In The Times of 24 August 1985, page 14 we see Raymond Keene vaunting a scoop:

‘Imagine my delight, then, at discovering the moves of a win by Alekhine against another player of the very highest class, which has so far eluded publication in any of the English language collections of Alekhine’s games. It has been known for some time that Alekhine’s lifetime score against Paul Keres consisted of five wins, one loss and eight draws, yet one of Alekhine’s wins proved impossible to track down.

At last, the score of the game emerged from an obscure Estonian document after a long search through the library of Bob Wade, the British Chess Federation coach. This week, I present this lost game to readers ...’

Before Mr Keene becomes even more carried away with his discovery, perhaps we could point out that the Alekhine-Keres game-score is given, with notes by J.H. Blake, on page 483 of the October 1935 BCM. Finding it there took 30 seconds.

The game was played in the 1935 Olympiad in Warsaw.

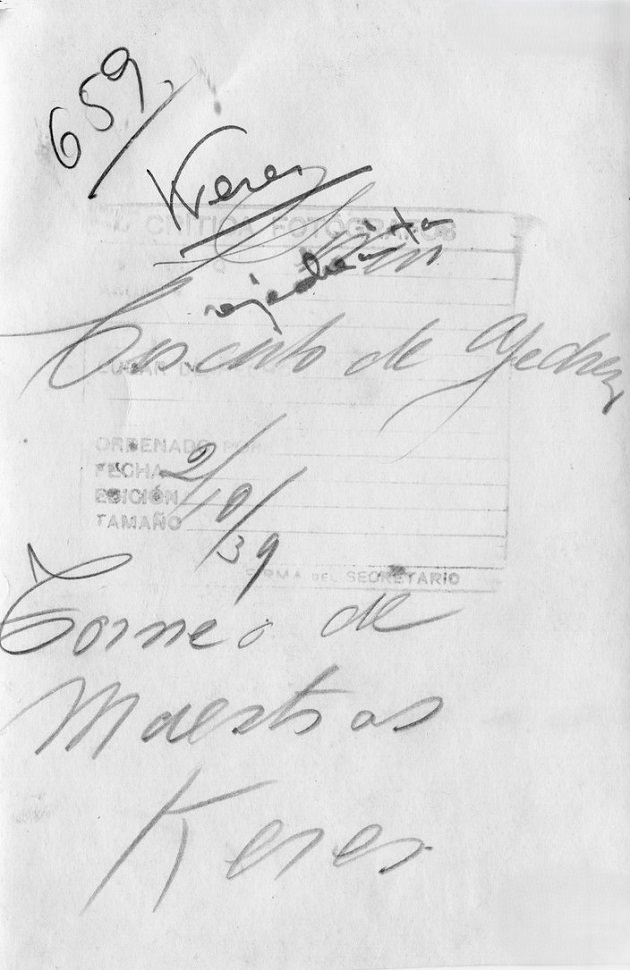

Several books, including The Middle Years of Paul Keres, claim that a victory over Czerniak (Caro-Kann, a win for White in 41 moves) was played in the Buenos Aires Team Tournament of 1939. In fact, it occurred in the last round of an all-play-all tournament of the same year in the Argentine capital (see pages 79-81 of Czerniak’s book of the event).

(1846)

From Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) comes a game played in a blitz tournament following the conclusion of the Olympiad:

Boris Kostić – Paul Keres

Stockholm, 1937

Two Knights’ Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Nf6 5 O-O d5 6 exd5 Nxd5 7 Ng5 Be7 8 Nxf7 Kxf7 9 Qh5+ g6 10 Bxd5+ Kg7 11 Bh6+ Kf6 12 Qg5 mate.

Source: Šachový tyden, 1937, page 119.

(2036)

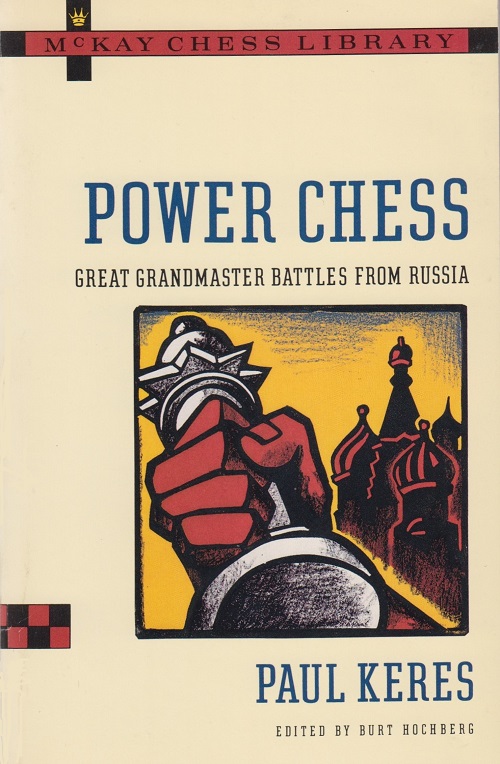

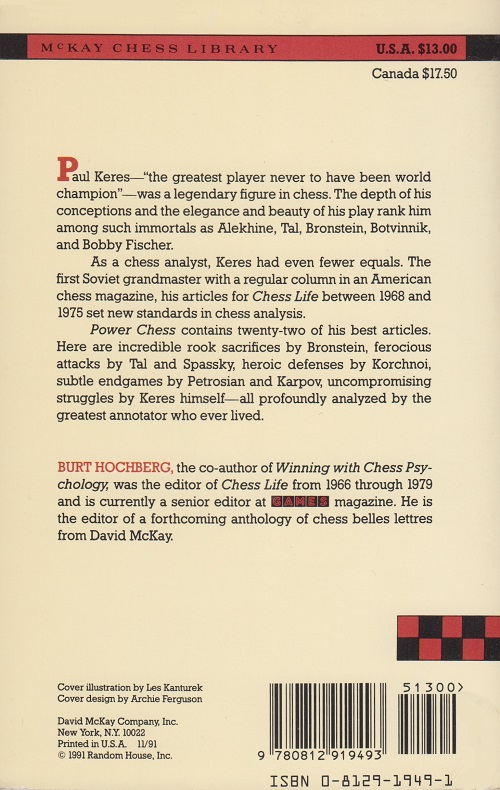

The 1991 paperback Power Chess by Paul Keres is ‘only’ an edited compilation of the great Estonian master’s articles in Chess Life and Chess Life & Review, yet it contains considerably more instruction and entertainment than most recent European books.

(Kingpin, 1993)

‘It is my considered opinion that Paul Keres is the greatest annotator who ever lived.’

Burt Hochberg, a much underrated writer, made that comment in a laudatory review of the final volume of the Keres trilogy Grandmaster of Chess on pages 236-237 of the June 1969 Chess Life. (The production standards of the US publisher, Arco, were, however, criticized.)

After possible competing claims in favour of Alekhine, Botvinnik and Fischer had been noted briefly (with mention too of Bronstein), Hochberg wrote:

‘Keres is profound, analytically sound, most readable and instructive. He omits nothing, save the most obvious and trivial. But perhaps the feature that sets him above all the others is his sense of form. A game of chess, in common with some other forms of art, has a beginning, a middle and an end, one phrase preparing the next, every move part of a planned organic whole. In his notes, Keres imparts to the game a sense of direction, a feeling of anticipation and the sure knowledge that nothing has been left to chance, that everything has been taken into account. At frequent intervals, Keres reminds us of each player’s earlier strategic goals, pointing out the strengths and weaknesses of each position and setting forth the plans of each player for the next stage of the game. He also shares with the reader his own thoughts during the game. One frequently encounters the phrase, “During the game, I intended ...”.’

Keres was a columnist in Chess Life and Chess Life & Review, and in 1991 Hochberg brought out an excellent anthology, Power Chess.

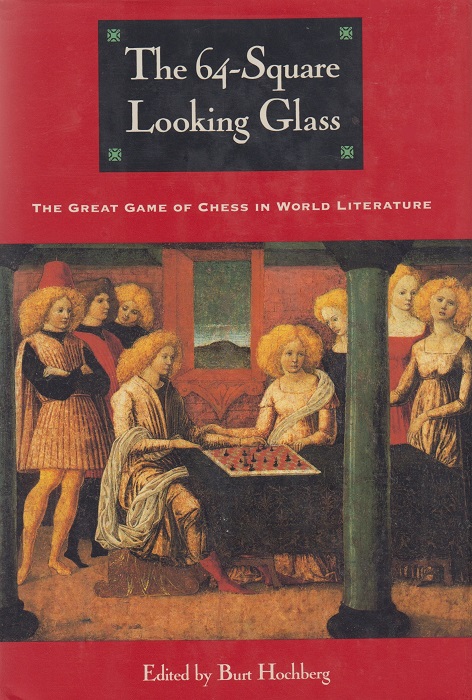

The chess belles lettres book by Hochberg referred to in the back-cover blurb was The 64-Square Looking Glass (New York, 1993).

(11215)

Paul Keres was only 15 when he had the following fine problem published on page 350 of the November 1931 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

Mate in five

(2246)

Of all possible publishing mishaps, one of the most unfortunate occurred in Paul Keres 50 parties (1916-1939) by J.-A. Le Monnier (Besançon, 1979): after game nine none of the headings identified the players. An errata sheet was added to list the players of the other 41 games, their names having vanished ‘à la suite d’une fausse manœuvre’.

(2286)

In this game from a simultaneous display with clocks, Keres was defeated by a 16-year-old:

Paul Keres – Enrique Velasco

Havana, 9 February 1960

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 g3 g6 4 Bg2 Bg7 5 f4 d6 6 Nf3 Nf6 7 O-O O-O 8 d3 Bd7 9 Kh1 Qc8 10 Ng1 Rb8 11 a4 Nd4 12 Nce2 Nxe2 13 Qxe2 a6 14 a5 b5 15 axb6 Rxb6 16 Ra2 Ne8 17 b3 Be6 18 Nf3 Nc7 19 Bb2 Nb5 20 Bxg7 Kxg7 21 Raa1 Bg4 22 Qe3 Bxf3 23 Bxf3 Nd4 24 Bd1 Qa8 25 Kg1 d5

26 b4 Qc6 27 c3 Ne6 28 bxc5 Nxc5 29 Qd4+ Kg8 30 exd5 Qd6 31 Rf2 Rd8 32 c4 e6 33 Ra5 Rb1 34 Rf1

34…Rxd1 35 Rxd1 Nb3 36 c5 Qc7 37 Qb4 Qxa5 38 Qxb3 Qxc5+ 39 d4 Qxd5 40 Qxd5 Rxd5 41 Kf2 a5 42 Ke3 a4 43 Kd3 Rh5 44 Rd2 a3 45 Ra2 Ra5 46 Kc4 Ra4+ 47 Kb3 Rxd4 48 Kxa3 Rc4 49 Kb3 Rc7 50 Ra5 Kg7 51 Kb2 Kf6 52 Rb5 h6 53 h4 h5 54 Ra5 Re7 55 Re5 Rd7 56 Kc2 Rd5 57 Re4 Kf5 58 Ra4 f6 59 Ra6 e5 60 fxe5 fxe5 61 Ra8 Rd6 62 Ra4 e4 63 Ra5+ Kg4 64 Ra3 Rd3 65 Ra6 Rxg3 66 Rxg6+ Kxh4 67 White resigns.

Source: Ajedrez en Cuba by C. Palacio (Havana, 1960), pages 291-292.

(2628)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) draws our attention to page 10 of the May 2001 issue of Gambito and some bizarre comments attributed to Manuel de Agustín in an interview conducted two years previously by Miguel Ángel Nepomuceno:

‘Manuel de Agustín [1916-2001] was one of Spain’s best chessplayers, and among his staunch friends he counted the Franco-Russian world champion Alekhine (whom he brought to Madrid in 1943 to play in a national tournament and to save him from his Nazi persecutors) and, especially, the Polish Jew GM Ossip Bernstein, whom he got out of a concentration camp in Teruel and saved from certain death.

“I tried to make the imprisoned Republicans’ lives a little less arduous by taking chess into their cells and playing numerous simultaneous games with them, as well as organizing tournaments for them. If during the time I was with them somebody asked me for help, I did not hesitate to offer it. When Keres came to Madrid to play in the great tournament of 1943, he was wearing an SS uniform, and the very day of his arrival I accompanied him to buy a suit, because his uniform was not appropriate in a country which had just emerged from a civil war. He was a Jew, and this was never written; like Alekhine, he enjoyed the protection of the Governor of Poland, but the only thing Alekhine wanted was to remain in Spain and leave, via Casablanca, for America, like so many other refugees. However, he died suddenly in Estoril when he was very close to his objective.”’

We need hardly stress that the above remarks should be treated with considerable circumspection.

(2801)

C.N. 4355 asked what the explanation was for the following:

They are reproductions from page 201 of Keres’ Best Games of Chess 1931-1940 by Fred Reinfeld, i.e. the original 1941 edition and the 1946 ‘reprinted’ version. The game was M. Luckis v P. Keres in the round-robin tournament in Buenos Aires, 1939. The full score was given on pages 27-28 of Torneo internacional del círculo de ajedrez octubre 1939 by M. Czerniak (Buenos Aires, 1946), where the possibility of 14 dxc6 Qd1 mate was noted.

‘Have I made a great discovery or has the printer made a great bloomer?’, asked Alfred Milner on page 83 of the April 1942 BCM after mentioning the one-move mate in the context of Reinfeld’s book. Page 110 of the May BCM reported:

‘Several readers have pointed out that Keres did not leave a mate on the move as suggested in our last issue. There is a transposition of moves in F. Reinfeld’s book and the possibility did not occur.’

(4362)

Concerning an interview with Bronstein by Antonio Gude on pages 38-42 of the March 1993 Revista Internacional de Ajedrez C.N. 4753 noted that he spoke warmly of Keres, a good friend and a quiet, courteous man who had, however, been accused of being a Nazi or a Nazi sympathizer. Bronstein acknowledged that Keres had played in tournaments in Germany and in occupied Europe, as well as fraternizing with German officials, but he called for understanding of the period and enquired rhetorically who was entitled to cast the first stone.

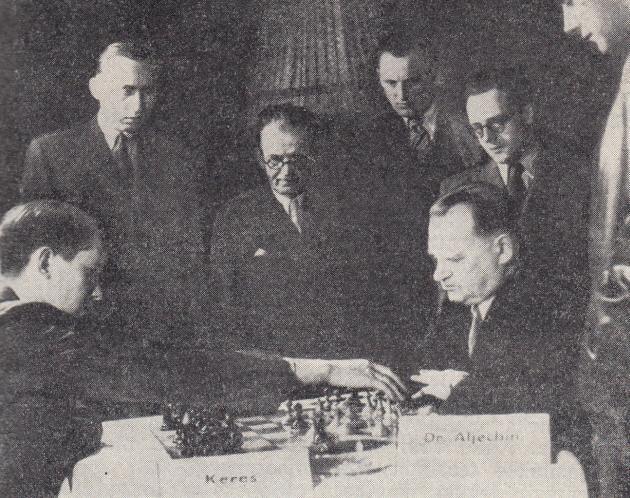

When only in his mid-teens the Estonian player Ilmar Raud (born in 1913) had ‘already made a name for himself’, according to Paul Keres on page 12 of volume one (‘The Early Games of Paul Keres’) of Grandmaster of Chess (London, 1964).

Buenos Aires, 1939. From left to right: P. Schmidt, G. Friedemann, P. Keres, I. Raud, J. Türn

After participating in the 1939 Olympiad Raud remained in Argentina but less than two years later he was dead, at the age of 28. Page 246 of the August 1941 issue of El Ajedrez Americano reported that he was ‘víctima de una repentina dolencia, que motivó su internación en un sanatorio’, whereas almost the entire first page of the October 1941 CHESS was devoted to an account of his last months, under the heading ‘Raud, the young Esthonian master, starves to death’. Below are the details of his demise as reported by CHESS:

‘[On 29 June 1941] he left his poor lodging-house never to return. He was found wandering in the streets and was arrested by the police. It was said there was a fight, and visitors subsequently observed obvious evidence of blows. He spent a bitterly cold night in the police yard, and the next day was sent to a lunatic asylum, where he died at 2 a.m., on 13 July, at the early age of 27 [sic]. The doctor’s certificate gave, as cause of death, general debility and typhoid fever, but the general verdict is – starvation. His body was cremated, and the ashes have been conveyed by the Esthonian consulate to Europe.’

The article strongly criticized the alleged treatment of players such as Raud in tournaments:

‘Conditions in South America’s chess world are extraordinary. Grau has achieved a position of extraordinary power and influence and is virtually dictator of Argentine chess; it is authentically stated that his chess organizing activities have netted him at least £5,000 in two years. Yet tournament after tournament goes through in the most haphazard and unsatisfactory fashion.’

As ever, we invite substantiation, or invalidation, of these assertions.

Ilmar Raud

The two photographs reproduced here come from Meie Keres by Valter Heuer (Tallinn, 1977). A group photograph (Buenos Aires, 1939) with Raud seated next to Keres is on page 106 of Paul Keres Photographs and Games (Tallinn, 1995).

The above-mentioned obituary in El Ajedrez Americano illustrated Raud’s play with his short victory as Black over Erik Lundin at the Buenos Aires Olympiad (24 August 1939), and the same game was given on page 50 of ¡¡Enroque!!, August 1941. Both Argentinian magazines had a slightly different game-score from the customary version, by omitting 10...c6 11 Bd3 and thereby having Lundin resign after 25...Ne4 (and not 26...Ne4). The game is in most databases.

(4905)

Concerning Raud, see also C.N.s 4944, 1002 and 10375.

Firstly, we reproduce C.N. 1678:

From P.C. Wason (Goring-on-Thames, England):

‘Who was Baron Döry? What are the details of the tournament designed to test his defence (Vienna, 1937)? And what are the details of his resistance to the Nazis which led to a sentence of death which was not carried out?’

Perhaps a reader would care to deal with the biographical matters raised by our correspondent. Articles about the Döry Defence (1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 Ne4) appeared in the Wiener Schachzeitung of. October 1936 (pages 293-295) and December 1936 (pages 359-360), the writers being Immo Fuß and Ladislaus Baron Döry respectively. The features were the subject of brief items in the BCM of January 1937 (page 22) and March 1937 (page 140).

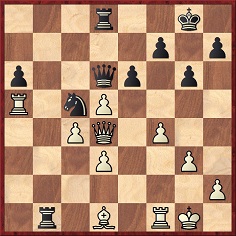

The May 1937 Wiener Schachzeitung carried a report on the Döry Defence tournament, held in the Café Central, Vienna on 19-26 May. Keres, Weil, Becker and Podhorzer (order of finish) played two games against each other. From the many games from the event which the Wiener Schachzeitung published, we pick the following:

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 Ne4 3 Nbd2 d5 4 g3 c5 5 dxc5 Nxc5 6 Bg2 Nc6 7 O-O e5 8 c4 d4 9 b4 Nd7 10 b5 Na5 11 Ne1 Be7 12 f4 exf4 13 Rxf4 O-O 14 Rf1 Ne5 15 Bb2 Bg5 16 Nc2

16...d3 17 exd3 Nxd3 18 Bd4 Nb4 19 Nf3 Nxc2 20 Qxc2 Be6 21 Rad1 Bxc4 22 Bc5 Qc8 23 Qf2 Bd8 24 Rxd8 Rxd8 25 White resigns.

Source: Wiener Schachzeitung, June 1937, pages 173-174.

Stefan Bücker (Nordwalde, Germany) now writes:

‘More on the Döry family is available on pages 11-12 of the January 1915 Wiener Schachzeitung, but the most interesting find has been on the Internet. A webpage of the Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes has photographs of the Baron and affirms that he was executed during the Second World War:

“Der Konzertpianist und Komponist Ladislaus Döry von Jobbahaza (geb. 1897) erklärte im privaten Kreis 1940 unter anderem, dass das wirtschaftliche und kulturelle Leben Österreichs im Absterben begriffen und Hitler ein machtgieriger Despot sei. Von den Eheleuten Graf Seilern denunziert, wurde er wegen Wehrkraftzersetzung zum Tode verurteilt und hingerichtet.”

However, the entry on “Döry Defence” in The Oxford Companion to Chess (page 112 of the 1992 edition) states:

“... pioneered by Ladislaus Döry, an Austrian Baron, in 1923 … In 1943 Döry was sentenced to death by the Nazis for sedition, but was released from prison by Allied troops in 1945.”

The two sources contradict each other as to whether or not Döry survived the War.’

We note that page 177 of the 1994 edition of Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia indicates that the Baron was still alive in 1947. Reference is made to a source not in our collection: ‘Schachspiegel, 1947, page 124’.

(5115)

See too C.N.s 5122 and 8507.

Fabio Molin (Rome) submits two photographs which he took at the Keres Museum in Tallinn at the end of September 2007:

(5230)

In August 2008 Calle Erlandsson also visited the museum, and below are three of the photographs he has sent us:

(5732)

A group photograph from page 173 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 1 June 1936:

(5244)

From Isaac Kashdan’s Introduction on page xii of First Piatigorsky Cup (published in Los Angeles, 1965):

‘Keres first became ill on an evening when he had two adjourned games to complete. He had decisive advantages against both Benko and Panno, but each had planned to continue. When word came that Keres would be unable to play, both opponents promptly resigned to him. This may be the first case in chess history that a player asked for a postponement and was rewarded with two points.’

Paul Keres (page 97 of the tournament book)

(5452)

Paul Keres

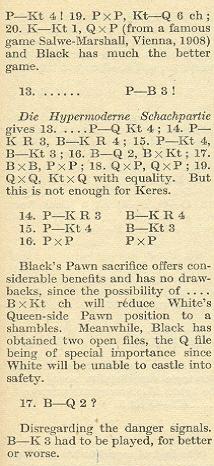

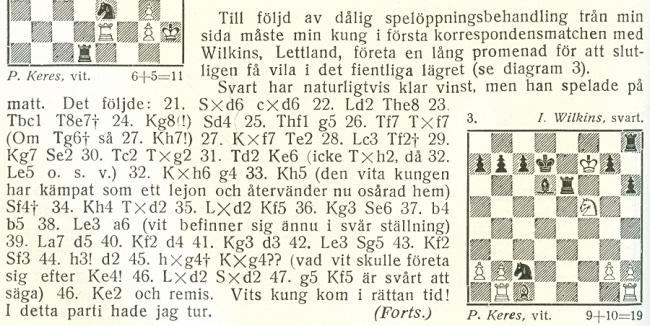

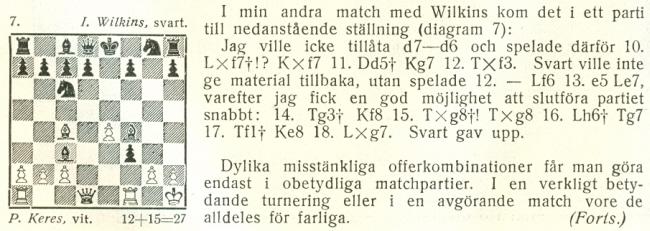

In the context of Keres’ early correspondence chess a name frequently seen is ‘Wilkins’, and two games in which Keres was White have been widely published as follows:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nc3 Qh4+ 4 Ke2 Nc6 5 d4 d5 6 Nxd5 Bg4+ 7 Nf3 O-O-O 8 Kd3 f5 9 Nxh4 fxe4+ 10 Kxe4 Bxd1 11 Bd3 Re8+ 12 Kxf4 Bd6+ 13 Kg5 h6+ 14 Kf5 Nxd4+ 15 Kg6 Bxc2 16 Bxc2 Nxc2 17 Rb1 Ne7+ 18 Nxe7+ Rxe7 19 Nf5 Re6+ 20 Kf7 Kd7 21 Nxd6 cxd6 22 Bd2 Rhe8 23 Rbc1 R8e7+ 24 Kg8 Drawn.

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 exf4 4 Nf3 g5 5 d4 g4 6 Bc4 gxf3 7 O-O Bg7 8 Bxf4 Bxd4+ 9 Kh1 Bxc3 10 Bxf7+ Kxf7 11 Qd5+ Kg7 12 Rxf3 Bf6 13 e5 Be7 14 Rg3+ Kf8

15 Rxg8+ Resigns.

They are usually dated circa 1933. In the case of the second game see, for instance, pages 86-87 of Paul Keres Chess Master Class by Y. Neishtadt (Oxford, 1983).

However, in articles entitled ‘Muntrationer från min korrespondenspraktik’ in the Swedish magazine Schackvärlden in 1935 (August, page 418 and September, page 522) Keres gave the conclusion of each game as follows:

Page 168 of the July 1933 Deutsche Schachzeitung reported that Keres was successful in the correspondence match:

‘Pernau. Paul Keres-Pernau gewann einen Fernwettkampf gegen J. Wilkins mit +7 –1 =2 ...’

A position from a third game between the two players was given on page 207 of the July 1935 issue of the German magazine.

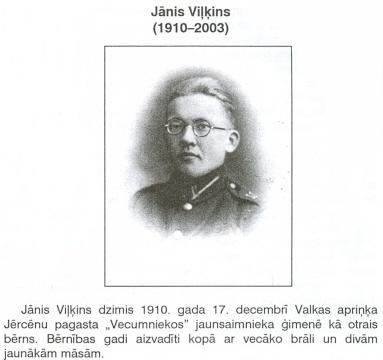

Although Keres too used the spelling ‘Wilkins’, the player in question was the Latvian Jānis Viļķins. The illustration below comes from Korespondencšahs Latvijā 1877-1944 by Ģ. Salmiņš (Liepāja, 2005):

(5477)

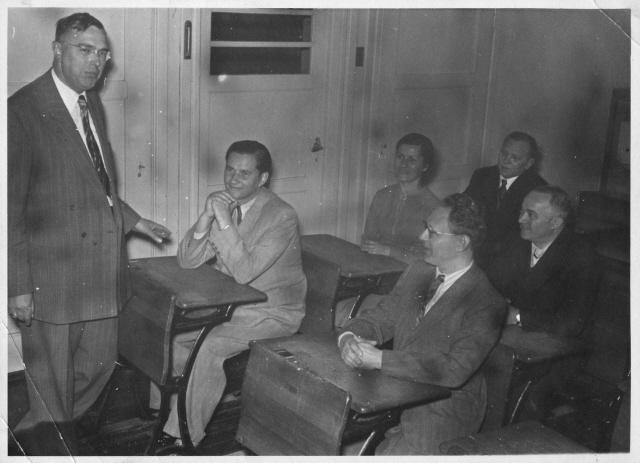

From the archives of Frank Anderson comes this photograph (Amsterdam, 1954), forwarded to us by John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA):

The caption on the original states: ‘M. Euwe, Keres, Mrs Botvinnik, Postnikov/Botvinnik, Flohr’.

(5798)

Paul Keres

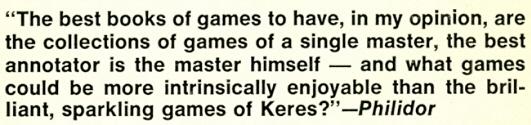

Chris Eve (Victoria, BC, Canada) mentions a citation on the back cover of Grandmaster of Chess The Complete Games of Paul Keres by P. Keres (New York, 1972):

We note that clarification of the ‘anachronism’ is supplied by the back cover of the original edition (London, 1969) of the third volume in the series:

The full text of the Spectator article by ‘Philidor’ would be appreciated.

(6210)

From Leonard Barden (London):

‘“Philidor” was C.H.O’D. Alexander. The Sunday Times, where he wrote under his own name, objected to him writing what it considered a rival column; hence the pseudonym.’

(6215)

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) asks about the correct spelling of Levenfish/Löwenfisch.

Both are commonly seen, with a distinct trend nowadays towards the former in many countries. The German rendition ‘Löwenfisch’ or ‘Loewenfisch’ was particularly common in English-language literature in the first half of the twentieth century, although the BCM sometimes had ‘Lövenfisch’. The 1971 volume Dizionario enciclopedico degli scacchi used ‘Levenfisch’. The last two spellings mentioned may be regarded as non-standard.

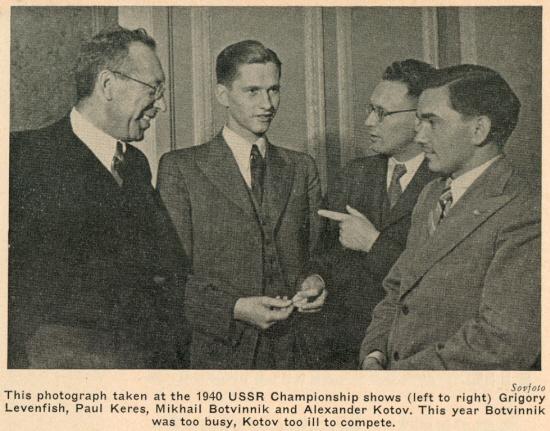

The above photograph was published in Chess Review, April 1947, page 9.

(6498)

The best and most detailed interview with Bent Larsen that we have seen was presented by C.H.O’D. Alexander on pages 86-94 of A Book of Chess (London, 1973) under the heading ‘Profile of a Grandmaster’. It took place shortly before the last round of Hastings, 1972-73. One brief passage:

‘Bronstein has influenced me – maybe Keres, but not so much; I like Keres’ book but I do not admire Keres as a chess artist. Keres is not an artist, he is a practical player. As a young player he was practical in a different way; his brilliancies were all rather conventional. I doubt that he has ever tried to be an artist and if he has he gave it up in the Second World War – and also gave up the hope of becoming world champion. I mean the following: Keres said to me once: “Sometimes I sit for 20 minutes and I know that some spectators are thinking that now there is something very deep coming: you know what’s happening? I can’t find any ideas and I am taking a nap – except for snoring and closing my eyes.” A player like Bronstein would never do that; he would be trying all the time.’

(6764)

C.N. 847 asked about the exact moves of the famous game Alekhine v Keres, Munich, 1942. After 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 b6 3 c4 Bb7 4 g3 e6 5 Bg2 Be7 6 O-O O-O 7 b3 d5 8 Ne5 c6 9 Bb2 Nbd7 10 Nd2 ...

... the question posed was whether play went 10...c5 11 e3 Rc8 12 Rc1 Rc7 (Gran Ajedrez, 107 Great Chess Battles, Alekhine’s Best Games of Chess 1938-45) or 10...Rc8 11 Rc1 c5 12 e3 Rc7 (books on Alekhine by Kotov and Müller/Pawelczak).

On page 268 of Chess Explorations we remarked that when annotating the game on pages 143-144 of the 1 October 1942 issue of Deutsche Schachblätter Alekhine gave 10...Rc8 11 Rc1 c5, contrary to the move order in his (posthumous) book Gran Ajedrez. Moreover, in the German magazine Alekhine stated that the opening moves were 1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 b6 3 d4 Bb7, whereas Gran Ajedrez indicated 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 b6 3 c4 Bb7.

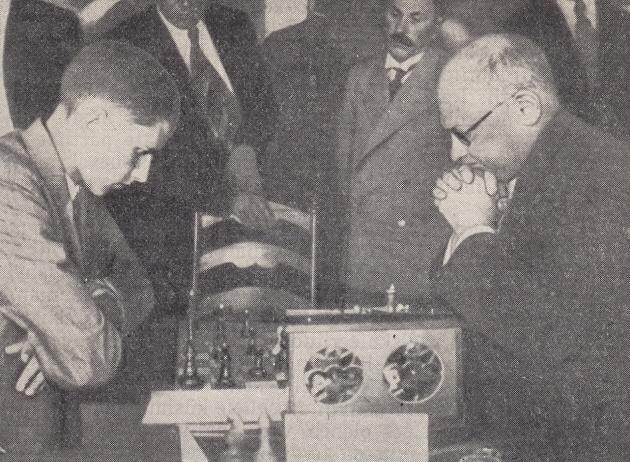

This photograph of Alekhine and Keres was taken a few months earlier, at Salzburg, 1942:

Source: Alt om Skak by B. Nielsen (Odense, 1943), page 273.

(7055)

From Javier Asturiano Molina:

‘Page 140 of the October 1942 Deutsche Schachzeitung gave the opening moves as 1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 b6 3 d4 Bb7, and the later sequence as 10...Rc8 11 Rc1 c5 12 e3 Rc7. The same version was provided by Ramón Rey Ardid when he annotated the game on pages 285-286 of Ajedrez Español, October-November 1942.’

(7073)

On page 106 of Chess Explorations a correspondent mentioned that Tallinn has a ‘Paul Keres Street’.

Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) reports that it is a wide lane. He was there recently:

(7154)

See too Street Names with Chess Connections.

The above photograph of Paul Keres was published opposite page 16 of Analysen van A.V.R.O.’s wereld-schaak-tournooi by M. Euwe (Amsterdam, 1938).

From page 82 of CHESS, 14 November 1938 comes a comment written by Paul Keres to B.H. Wood shortly before the tournament began:

‘It will be an achievement not to be last.’

(7400)

A quote published on page 186 of Combinations The Heart of Chess (New York, 1960) by Irving Chernev:

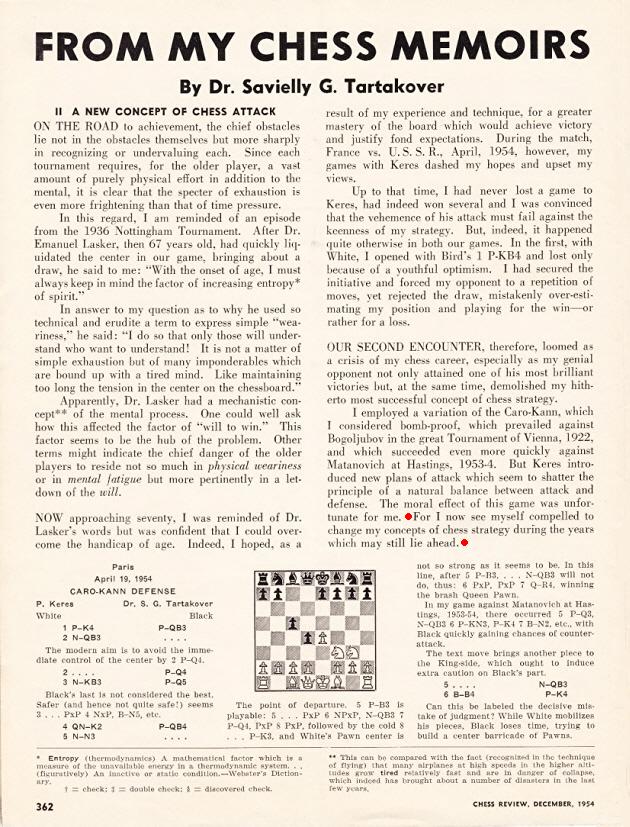

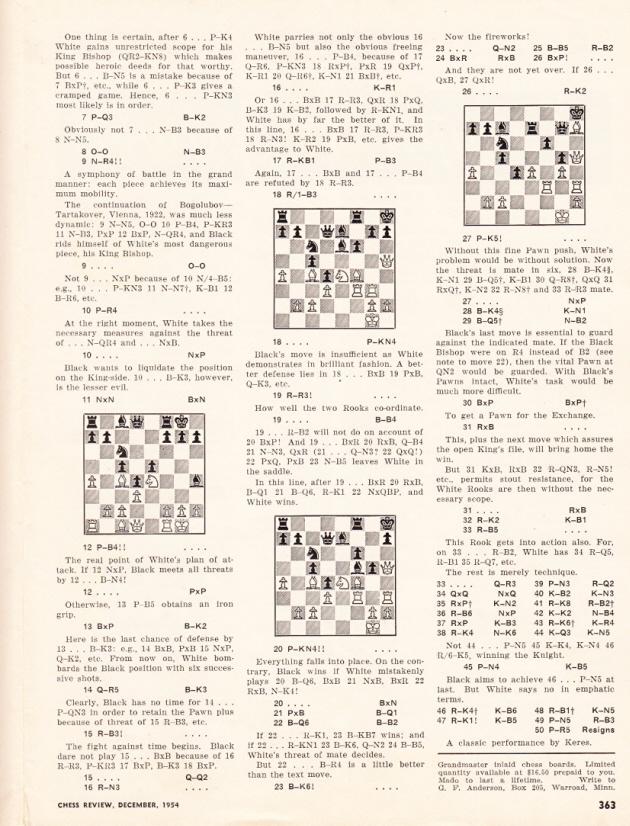

No source was given, but the observation comes from an article by Tartakower on pages 362-363 of the December 1954 Chess Review:

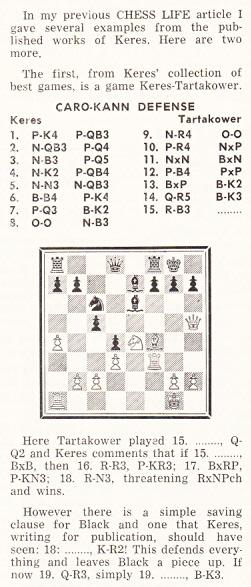

The Keres v Tartakower game was discussed by Fischer on page 172 of the July-August 1963 Chess Life:

In the diagram White’s bishop is missing from c4.

In his previous article (Chess Life, June 1963, page 142) Fischer mentioned that he had been reading Keres’ ‘recent book of his best games (in Estonian)’. Below is the relevant note in the Keres v Tartakower game, from page 381 of that work, Valitud partiid 1931-1958 (Tallinn, 1961):

The position before Fischer’s discovery, 18...Kh7:

(7801)

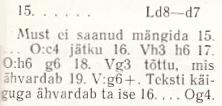

Below are two photographs from Valitud partiid 1931-1958 by Paul Keres (Tallinn, 1961), pages 37 and 201:

Paul Keres v Savielly Tartakower, Kemeri, 1937

Paul Keres v Alexander Alekhine, Prague, 1943

(7802)

Simon Browne (Somerville, Australia) notes the remarks by Alekhine about possible world championship rivals on page 178 of 107 Great Chess Battles (Oxford, 1980):

‘Before 1940 I was quite certain that two masters, Botvinnik and Flohr, wished to fight for this title. Neither of the two matches could be brought about, and the above-mentioned challengers know very well that I had decided to face them.

As regards Keres, his position in 1938-39 was less resolved; he gave the impression of preferring to let a few years pass. But in 1943, perhaps influenced by the disastrous results he obtained against me in recent meetings (+3 =3 –0 in my favour) he resolutely declared that he had not the slightest intention of challenging me to a match. Fine too, in 1940, made an analogous declaration.’

These remarks were originally published on page xix of Alekhine’s book ¡Legado! (Madrid, 1946), and Mr Browne asks whether it is possible to find statements by Keres or Fine along the lines indicated by Alekhine.

Readers’ assistance will be appreciated. Firstly on this topic, we would draw attention to an earlier article by Keres, ‘The World Chess Championship’, published on pages 51-53 of the March 1941 Chess Review.

(7839)

‘The older I grow, the more I value pawns.’

Whether Paul Keres ever wrote down this familiar observation is not known to us, but it was ascribed to him by I.A. Horowitz in an article on page 369 of the December 1955 Chess Review. Horowitz stated that Keres had made the remark ‘to a member of the US team only last summer’ (i.e. when Keres was aged 38).

(8018)

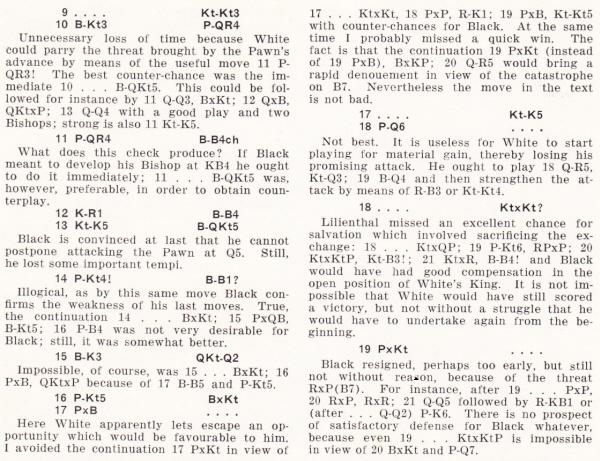

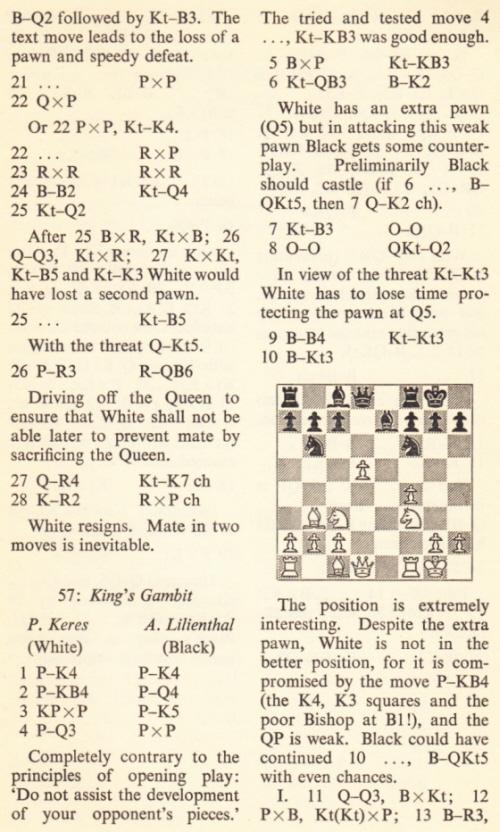

Paul Keres – Andor Lilienthal

USSR Absolute Championship, Moscow, 27 April 1941

Falkbeer Counter-Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 f4 d5 3 exd5 e4 4 d3 exd3 5 Bxd3 Nf6 6 Nc3 Be7 7 Nf3 O-O 8 O-O Nbd7 9 Bc4 Nb6 10 Bb3 a5

11 a4 Bc5+ 12 Kh1 Bf5 13 Ne5 Bb4 14 g4 Bc8 15 Be3 Nbd7 16 g5 Bxc3

17 bxc3 Ne4

18 d6 Nxe5 19 fxe5 Resigns.

The present item will focus on the concluding moves, but a word first about the opening. Some databases give the move order as 4 Nc3 Nf6 5 d3 exd3 6 Bxd3 Be7; seldom can a database be consulted for an old game without an error or discrepancy of some kind being found.

The annotator of a miniature may be tempted to view matters (or, at least, pretend to) as a plain lesson in crime and punishment, the loser being doomed almost from the start and the winner’s play being presented as irreproachable. In Keres v Lilienthal, after 15...Nbd7 Reuben Fine commented:

‘One’s reaction to this move is that if such things have to be done he might as well resign.’

And after 16...Bxc3:

‘To have some air, but he loses a piece. The position is hopeless.’

Following 17 bxc3 Ne4 Fine gave 18 d6 two exclamation marks and wrote:

‘Typical. Black’s game is ripped apart.’

Black’s reply, 18...Nxe5, was labelled ‘desperation’ since 18...Nxd6 allowed an ‘elegant’ mating variation.

Page 82 of Chess Marches On! by Reuben Fine (New York, 1945)

A similar story of inexorable comeuppance was told by Fred Reinfeld. At move 15: ‘Black’s helplessness is touching.’ At move 16 an alternative was rejected because in that case ‘Black has no reasonable continuation’. And, as in the Fine book, two exclamation marks for 18 d6.

Page 225 of Keres’ Best Games of Chess, 1931-1948 by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1949)

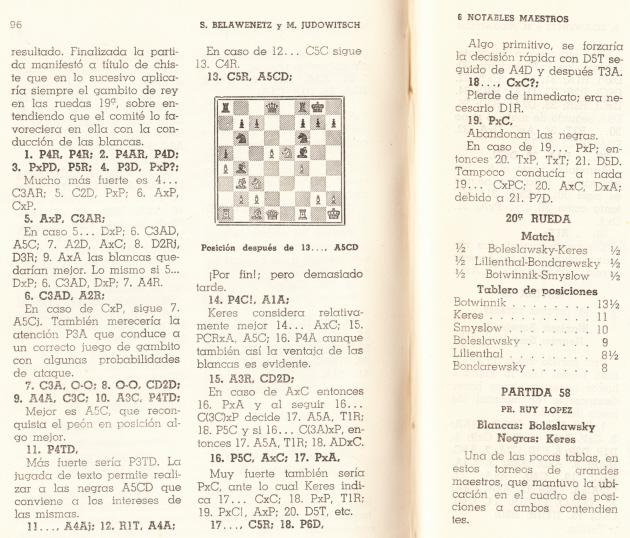

Strange to relate, in 1941 the notes to Keres v Lilienthal were less eulogistic of White’s play at various points. Below is the game’s appearance on pages 96-97 of the tournament book, 6 notables maestros by S. Belawenetz and M. Judowitsch (Buenos Aires, 1941):

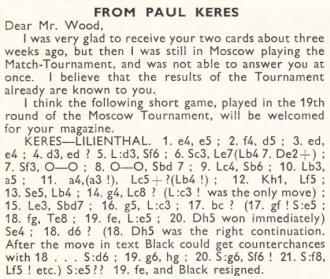

Moreover, Keres himself was critical of his play in two

publications in 1941. The first was in a letter dated 9 May 1941

to B.H. Wood given on page 178 of the September 1941 CHESS.

It will be seen that he even appended a question mark to 18 d6:

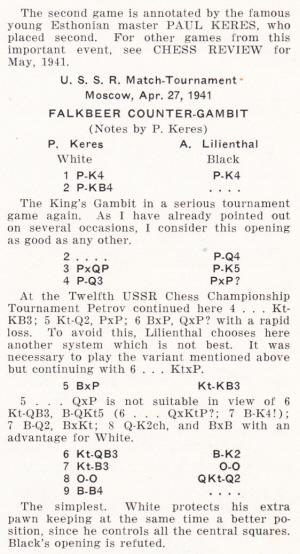

Keres annotated the game in detail on pages 207-208 of the November 1941 Chess Review, criticizing his play and stating that at move 18 ‘Lilienthal missed an excellent chance for salvation’:

Finally, below are Botvinnik’s annotations in the English edition of his book on the tournament, on pages 179-180 of Championship Chess (London, 1950):

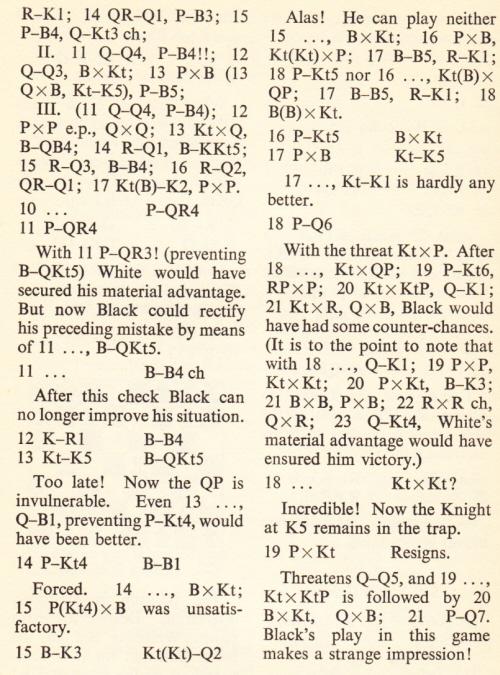

A photograph taken during the Leningrad part of tournament was published on page 206 of the November 1941 Chess Review:

(8353)

Black to move

The above position arose after 11 a4 in Keres v Lilienthal, USSR Absolute Championship, Moscow, 27 April 1941. As shown in C.N. 8353, 11...Bc5+ received this remark from Keres in his annotations on pages 207-208 of the November 1941 Chess Review:

‘What does this check produce? If Black meant to develop his bishop at KB4 he ought to do it immediately; 11...B-QKt5 was, however, preferable, in order to obtain counterplay.’

A briefer criticism of 11...Bc5+, on page 81 of Chess Marches On! by Reuben Fine (New York, 1945), is what passes in the chess world for a dictum/maxim/witticism:

‘Evidently forgetting that nobody ever died of a check.’

(10678)

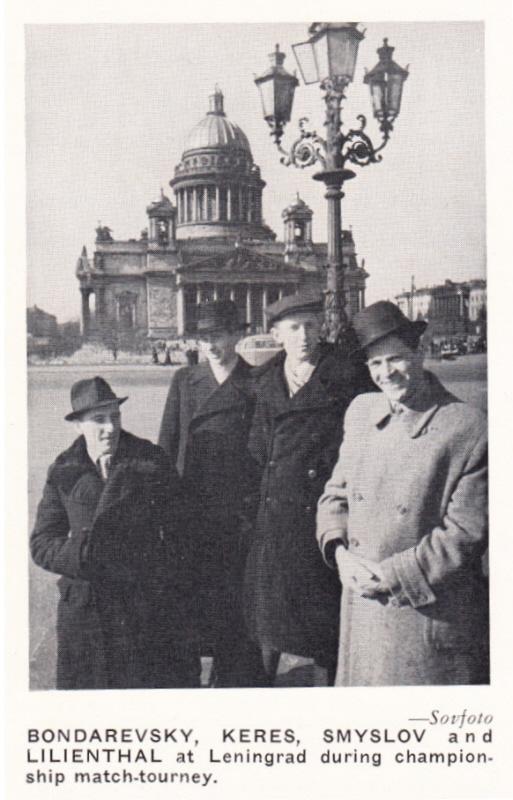

Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA) is surprised by the above, from page 210 of The Art of Attack in Chess by V. Vuković (London, 1998), because after 8...Nf6 ...

... the possibility of 9 Bxb7 is not mentioned.

Our initial comment is that in earlier editions of the book (in the descriptive notation – see page 237) the first 13 moves were not given.

Other authors have passed over in silence 9 Bd3 (which, incidentally, was not a novelty in 1939). See, for example, pages 262-263 of Modern Chess Opening Theory by A.S. Suetin (Oxford, 1965).

Keres himself referred to the line in his monograph on the French Defence (Örebro, 1957, page 176, and Moscow, 1958, page 149), giving 9 Bxb7 (‘!’) and making no mention of his game against Petrov.

Below are some annotators’ comments on the relevant phase of the Keres v Petrov game:

Al Horowitz, Chess Review, May 1939, page 106.

Schackvärlden, June 1939, page 209.

Keres’ Best Games of Chess 1931-1940 by F. Reinfeld (London, 1941), page 193.

Paul Keres Chess Master Class by Y. Neishtadt (Oxford, 1983), page 110.

Even so, there are writers who have suggested that 9 Bd3 may have been preferable to 9 Bxb7:

Turniere, Taten und Erfolge by E. Ridala (Berlin, 1959), page 70.

Paul Keres’ Best Games, volume two, by E. Varnusz (Oxford, 1990), page 139.

(8387)

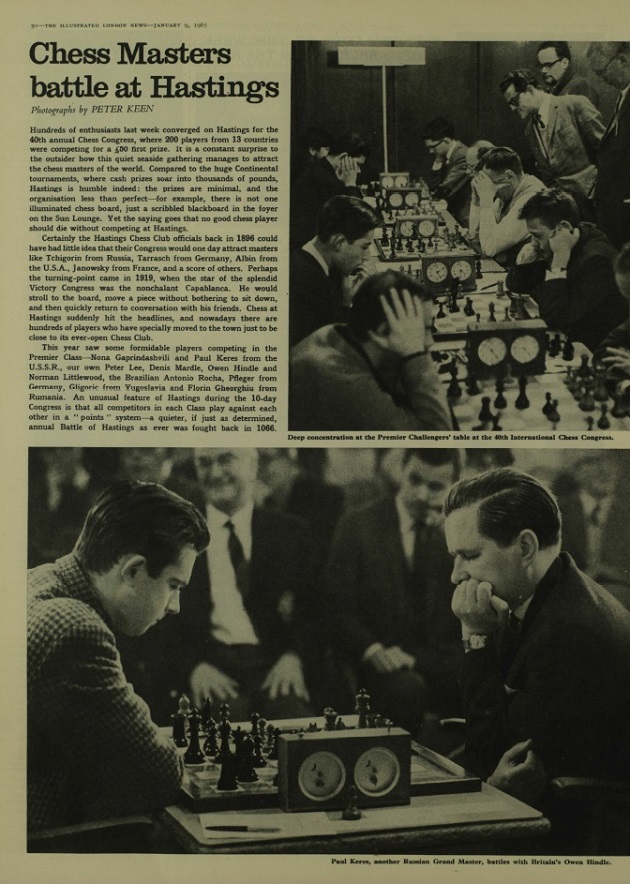

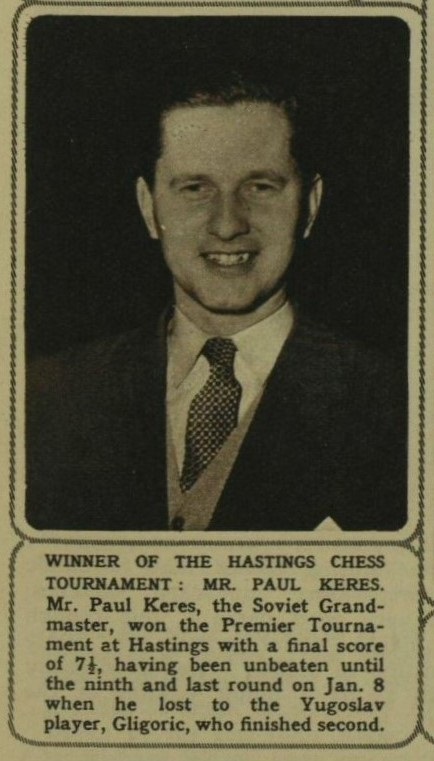

From a feature on pages 30-31 of the Illustrated London News, 9 January 1965, supplied by Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

(8974)

Another contribution from Olimpiu G. Urcan:

Illustrated London News, 18 January 1958, page 105

(9020)

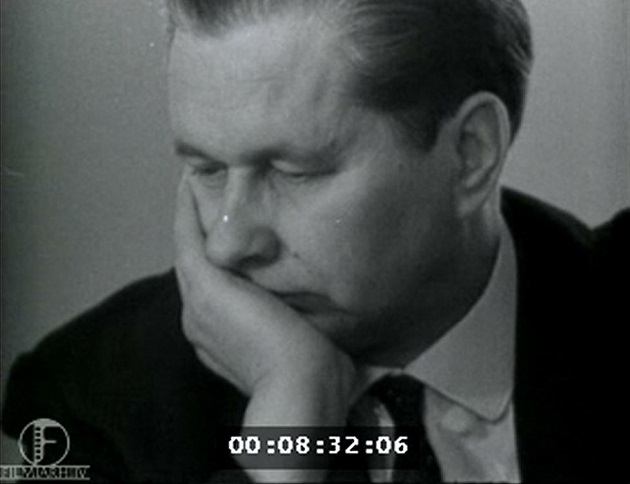

Concerning Chess Masters on Film, Olimpiu G. Urcan writes:

‘In addition to audio files with Keres interviews and speeches, the Estonian Film Archives contain a significant number of film files featuring him, and some of the material has been digitized and made available on-line. Among the highlights: a 1938 clip of Keres in a tournament (and playing blitz). A 1941 feature on his mathematics examination at the University of Tartu:

1945 film showing Keres in tournament play (with other Soviet masters):

There is a seven-minute montage on the 1947 USSR Championship, and a brief 1956 clip showing Keres in a simultaneous exhibition at a house of pioneers in Tallinn. Also, coverage of his golden jubilee celebration (1966) and remarkable 1975 footage of his funeral:’

(9892)

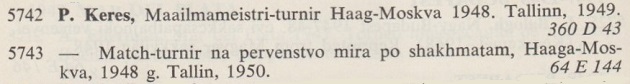

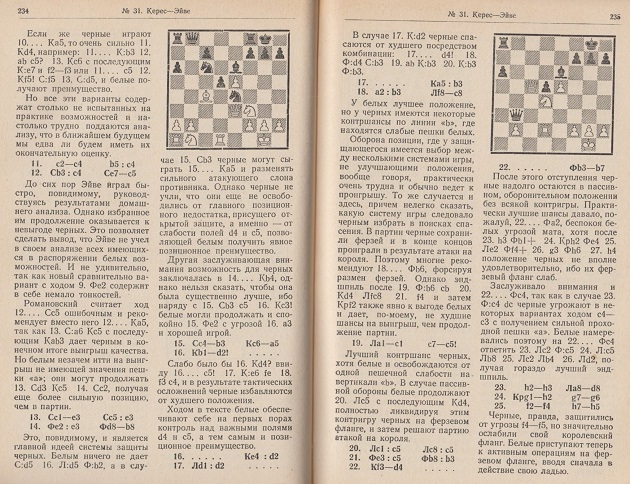

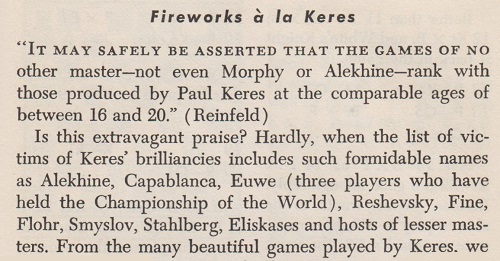

On any list of favourite chess players, personalities and writers, Paul Keres is likely to be ranked highly. At about 3:50:00 in a broadcast during round 11 of the US championship in St Louis on 25 April 2016, Yasser Seirawan asked Garry Kasparov about his favourite chess books. The answer included a reference to ‘Keres, 1948’. The book in question, on the 1948 world championship match-tournament, has also been praised recently by Boris Gelfand, in a ChessBase interview conducted by Sagar Shah.

From page 262 of the catalogue Bibliotheca Van der Linde-Niemeijeriana (The Hague, 1955):

As an indication of the quality of Keres’ work, two pages (on his 16th-round win against Euwe in Moscow on 22 April 1948) are given here, from the 331-page Tallinn, 1950 edition:

The book is not easily found nowadays, but an augmented edition published in Kharkov in 1999 is still available.

(9893)

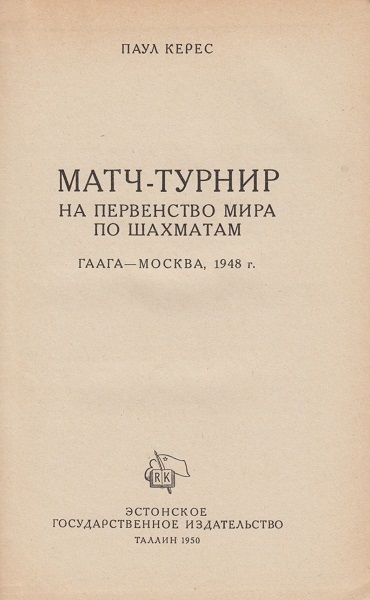

A page from the limited edition of Wereldkampioenschap Schaken 1948 by Max Euwe (Lochem, 1948):

See Chess Autographs.

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, Canada) points out an Estonian webpage with many photographs of Paul Keres.

(10108)

A further rich selection of images concerning Keres is available at the website of the Eesti Muuseumide Veebivärav, through a search for either ‘Keres’ or the Estonian word for chess, ‘Male’.

(10121)

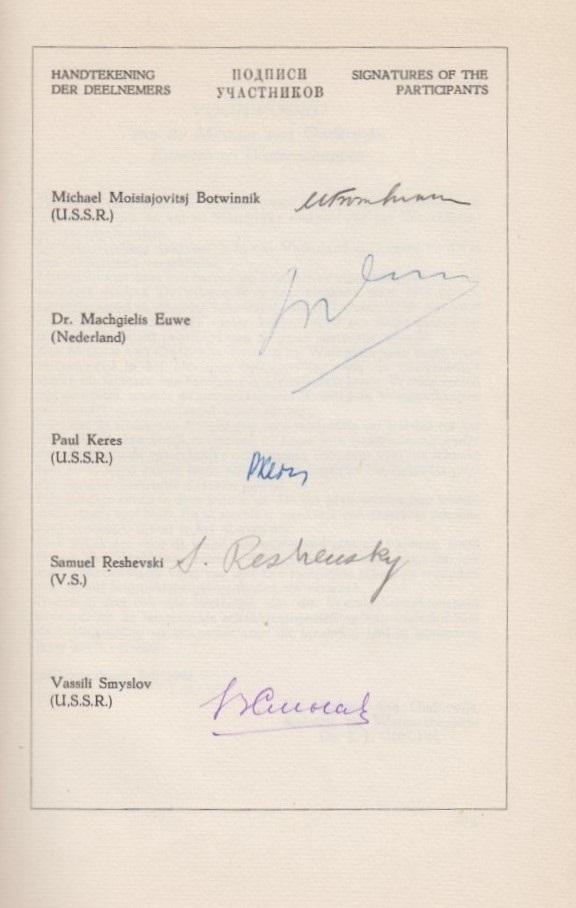

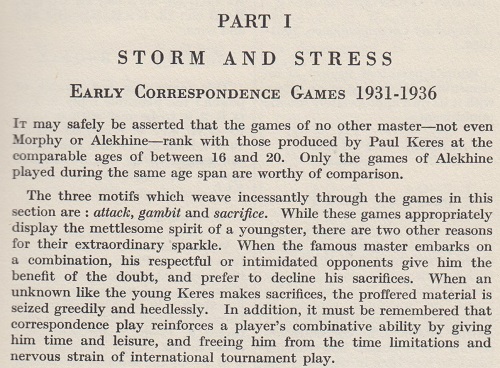

Page 153 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948) provided a reminder of the outstanding status of Paul Keres in his youth:

The list of victims of Keres’ brilliancies is illogical, given that Reinfeld’s cut-off point was the age of 20. His remark, which had an additional reference to Alekhine, was on page 1 of Keres’ Best Games of Chess 1931-1940 (London, 1941):

(10285)

On page 10 of Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship (New York, 1973) Reuben Fine wrote regarding Alekhine:

‘When World War II ended, in 1945, all the leading masters of that day, incensed by his behavior, objected to his participation in international tournaments. The Soviets broke the boycott by having Botvinnik challenge Alekhine to a match for the title in 1946. Actually this was illegal, since Keres and I had prior claims. But Keres, born in Estonia, was a Soviet citizen, while I was no longer so interested.’

From pages 224 of the ‘revised and expanded edition’ of The World’s Great Chess Games by Fine (New York, 1976):

‘Legally there were various possibilities. Euwe might have reclaimed the title, as the last official champion before Alekhine. Or Keres and Fine could have been declared co-champions on the basis of their joint victory in the AVRO tournament. Or Euwe, Fine and Reshevsky might have played a three-cornered tournament to decide the championship. Or the free world might have chosen a champion, and the communist world been left to choose its own; then the two could have met for the world championship.’

On the next page Fine wrote with respect to AVRO, 1938:

‘As indicated before, on the basis of this victory and in light of the circumstances of international chess in the war period, Keres and I should have been declared co-champions for the period 1946-48, between the death of Alekhine and the 1948 tournament.’

Finally, a comment by Fine on page 151 of Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958):

‘Keres and I tied for first in the AVRO tournament; he was declared winner by the tie-breaking Sonnenborn-Berger [sic] system. Alekhine dodged a match in his usual skillful manner. Then the war intervened and all official chess activity stopped.’

There is a frequent lack of rigour in claims that Alekhine ‘dodged’ opponents, and it is unimpressive to find C.J.S. Purdy writing the following in a review of Lessons from My Games on pages 146-147 of Chess World, September-October 1967:

‘Reuben Fine became one of the world’s greatest players. At the time when his claims to play a match for the world title were unanswerable, he did not get to play a match because Alekhine, once he had regained his title from Euwe, did everything possible to evade a match.’

As regards possible challenges to Alekhine after AVRO, 1938, an observation on page 215 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004) is noteworthy:

‘Fine seems not to have made any effort at all ...’

Related feature articles:

(10288)

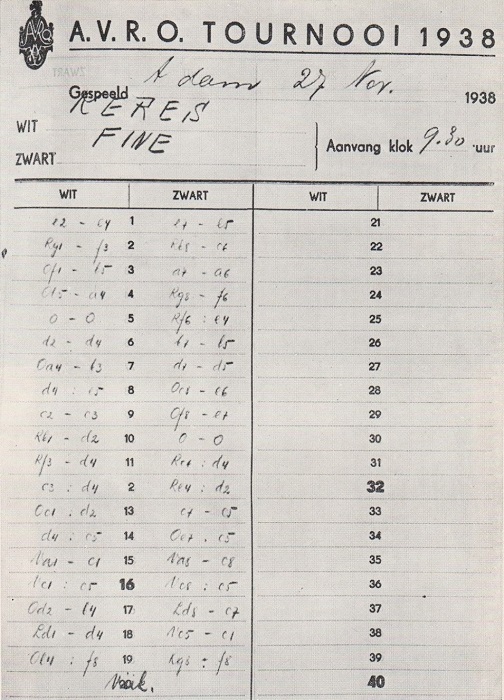

Concerning the Fine v Keres game at AVRO, 1938 see Critical Moments in Chess.

From Chess Score-Sheets:

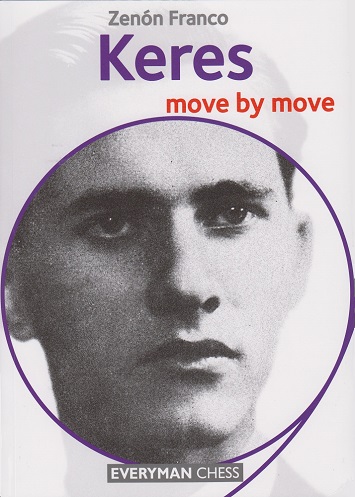

Keres move by move by Zenón Franco (London, 2017) is the latest addition to our list of nearly 30 books about Keres.

Question: how many of the earlier works are mentioned in Franco’s bibliography (page 6)? Answer: none.

(10411)

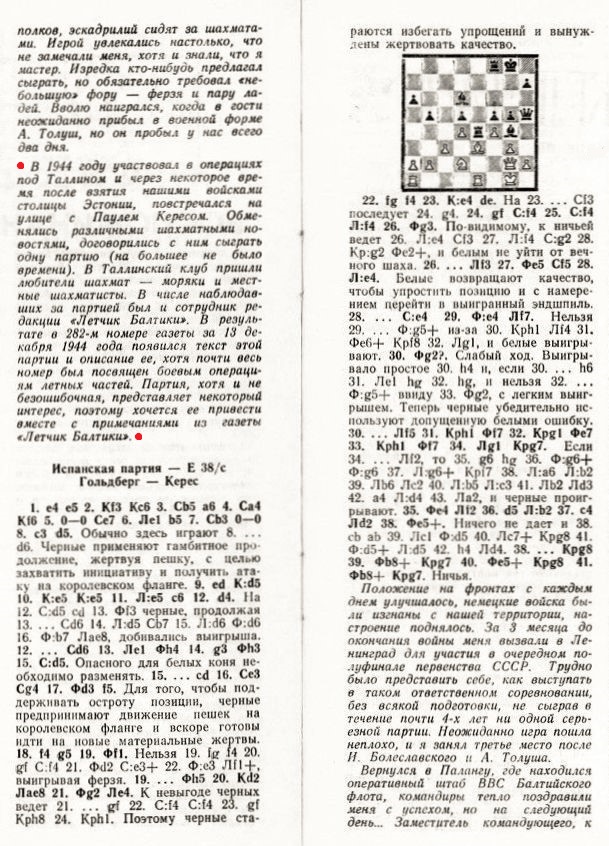

From Dan Scoones comes a Marshall Gambit game published on pages 2-3 of the 4/1976 issue of Shakhmaty Riga, in an article by Grigory Abramovich Goldberg:

Our correspondent’s translation of the marked passage:

‘In 1944 I was taking part in military operations near Tallinn. A short time after our forces recaptured the city, I ran into Paul Keres in the street. We exchanged various pieces of news from the chess world and agreed to play a game (there was not time for more than one). This drew some chess aficionados to the Tallinn club, including sailors and local chessplayers. Among the spectators at this game was an editorial assistant of the newspaper Baltic Aviator. As a result, issue #282 for 13 December 1944 carried the text of the game and a short account of it, but of course most of the issue was concerned with military operations by our air forces. The game is not free of errors, but is still of some interest; I should therefore like to present it here, along with the comments from Baltic Aviator.’

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 O-O 8 c3 d5 9 exd5 Nxd5 10 Nxe5 Nxe5 11 Rxe5 c6 12 d4 Bd6 13 Re1 Qh4 14 g3 Qh3 15 Bxd5 cxd5 16 Be3 Bg4 17 Qd3 f5 18 f4 g5 19 Qf1 Qh5 20 Nd2 Rae8 21 Qg2

21...Re4 22 fxg5 f4 23 Nxe4 dxe4 24 gxf4 Bxf4 25 Bxf4 Rxf4 26 Qg3 Rf3 27 Qe5 Bf5 28 Rxe4 Bxe4 29 Qxe4 Rf7

30 Qg2 Rf5 31 Kh1 Qf7 32 Kg1 Qe7 33 Kh1 Qf7 34 Rg1 Kg7 35 Qe4 Rf2 36 d5 Rxb2 37 c4 Rd2 38 Qe5+ Kg8 39 Qb8+ Kg7 40 Qe5+ Kg8 41 Qb8+ Kg7 Drawn.

(10947)

‘Ei ole ju keegi loodud meistriks, vaid tee selle saavutamiseni kulgeb pikaaegse ōppimise, vōistlemise, rōōmude ja murede kaudu.’

That remark by Paul Keres on page 9 of his book Valitud partiid 1931-1958 (Tallinn, 1961) is best known from the English edition. From page v of Grandmaster of Chess. The Early Games of Paul Keres translated and edited by Harry Golombek (London, 1964):

‘Nobody is born a master. The way to mastery leads to the desired-for goal only after long years of learning, of struggle, of rejoicing and of disappointment.’

The remark was in large letters at the top of page 805 of the December 1975 Chess Life & Review, in a tribute to Keres which claimed to show the last photograph of him (with Euwe in Amsterdam on 31 May 1975). On the Internet the quote is customarily, if not exclusively, found with ‘desired’, and not ‘desired-for’. That shorter version is on page 5 of John Nunn’s edition of the book, Paul Keres: The Road to the Top (London, 1996).

(11194)

C.N. 11259 referred to Wolfgang Heidenfeld’s description of Śliwa v Bronstein, Gotha, 1957 as the ‘immortal loss’. In the same source (page 271 of the September 1965 BCM) Heidenfeld called Bronstein v Keres, Göteborg, 1955 ‘probably the most profound game ever’. Minić v Tolush, Oberhausen, 1961 was ‘the most fantastic defensive win’. He also praised the ‘beautifully played’ game Mikėnas v Lebedev, Tbilisi, 1941.

(11269)

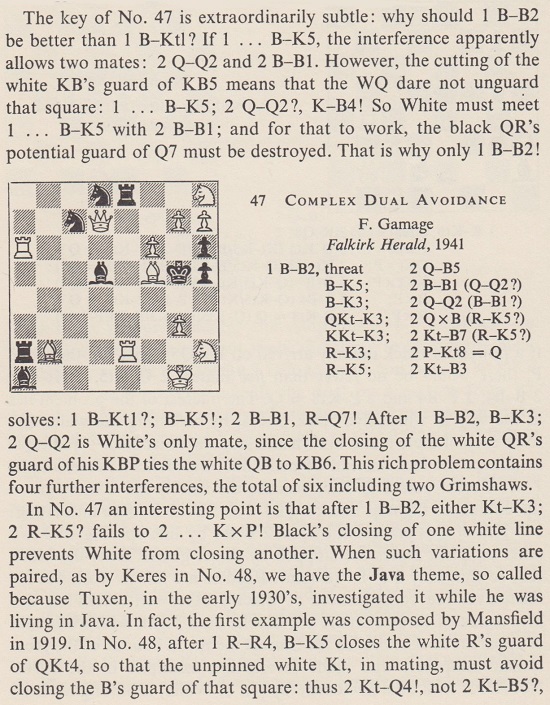

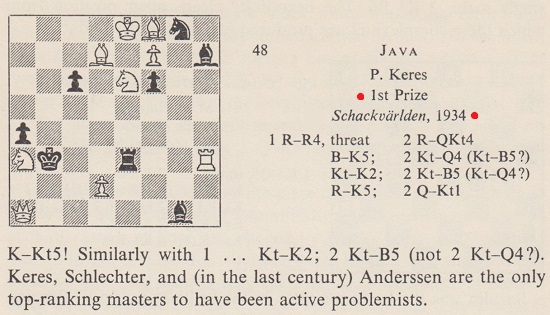

Mate in two

This composition by Paul Keres has been sent to us by Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England), who writes:

‘The source is usually given as First Prize, Schackvärlden, 1934, but in his collection of 110 of Keres’ compositions Paul Keres Der Komponist The Composer (Vienna, 1999) Alexander Hildebrand indicates Third Prize, Postimees, 1942. His Preface (page 3) states: “the most special thanks are due to the composer’s wife, Mrs Maria Keres, whose willingness to make his collection of problems available has made this book possible.”

Can the source details of this two-mover by Keres be clarified? It combines an idea known to problemists as the Java theme (two white pieces guard a flight square (b4); the black defence closes one line, and White must be careful not to close the other) with unpins and a Grimshaw (mutual interference between rook and bishop) on e4.’

(11335)

Mate in two

Henry Tanner (Helsinki) notes that this problem is not in Schackvärlden, 1934, although the Swedish magazine had other compositions by Keres around the same time.

The earliest appearance of the above-mentioned incorrect source that our correspondent has found is on pages 60-61 of Chess Problems: Introduction to an Art by Michael Lipton, R.C.O. Matthews and John M. Rice (London, 1963):

(11345)

One of many photographs submitted to us by Carlos León Cranbourne (Buenos Aires):

(11341)

A caricature on page 11 of Destino (Barcelona), 25 January 1964:

(11371)

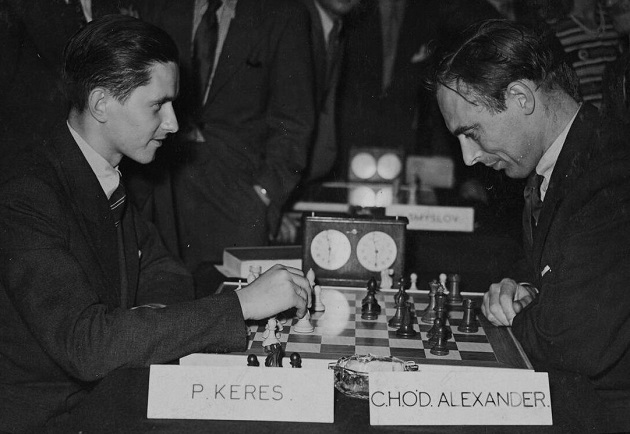

This photograph of Paul Keres and C.H.O’D. Alexander is reproduced courtesy of the Hulton Archive. It was taken during Hastings, 1954-55, but the board position is unrelated to their game in the tournament.

(12090)

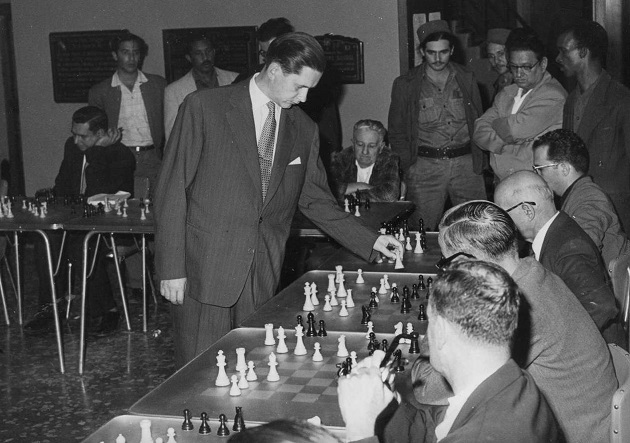

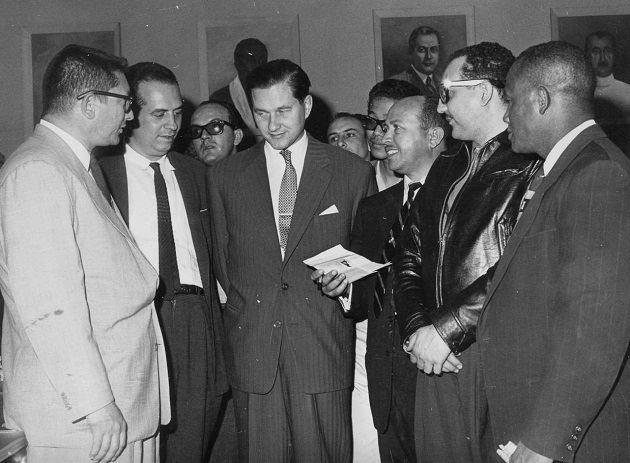

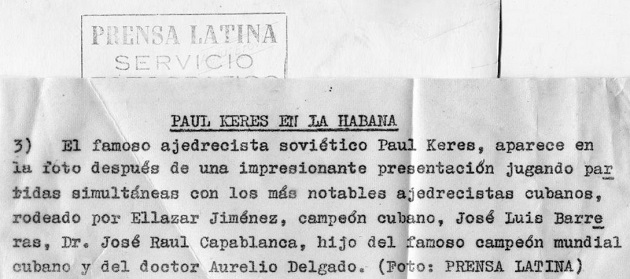

Olimpiu G. Urcan has submitted the following, courtesy of the Prensa Latina Archive:

The photographs are undated, and information will be welcome. Our present feature article includes (C.N. 2628) a game from a simultaneous exhibition with clocks in Havana on 9 February 1960. The source was pages 291-292 of Ajedrez en Cuba by C. Palacio (Havana, 1960).

(12173)

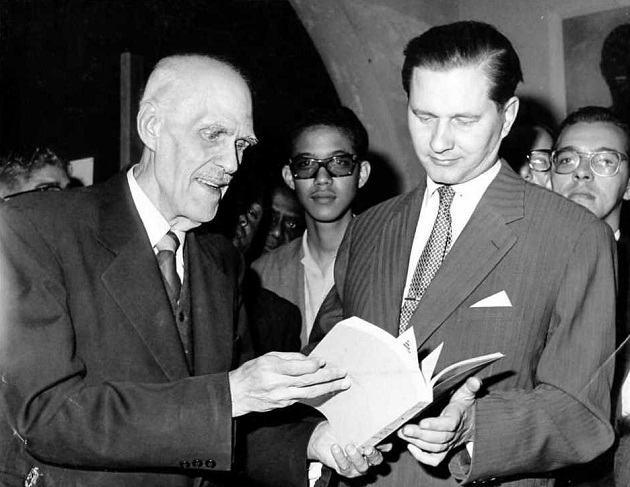

Addition on 14 July 2025:

Confirming the year 1960, and adding that Keres arrived in Havana on 6 February, Yandy Rojas Barrios (Cárdenas, Cuba) forwards from his archives two more photographs from the visit:

With Eduardo Heras León (1940-2023), then the national youth champion, and later a prominent literary figure.

With José Antonio Gelabert y Barruete (1893-1969).

Olimpiu G. Urcan sends this 1939 photograph of Paul Keres:

It comes from the same source, the Crítica archive, as the Alekhine picture in C.N. 12182, and presents the same problem. Other photographs of Keres show him to be right-handed and wearing a watch on his left wrist. Consequently:

(12191)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.