Edward Winter

‘We read again that the King’s Gambit is dead. It never quite recovered from its previous deaths.’

Source: D.J. Morgan, BCM, August 1970, page 226.

Joseph Henry Blackburne (simultaneous) – Amateur

Canterbury, 1903

Muzio Gambit

(Notes – and how characteristic they are – by Blackburne)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 (‘On this occasion, to follow the fashion, I offered the King’s Gambit wherever I had the chance; and to my utter astonishment, nearly all were accepted. “That’s the way to learn chess”, said I.’) 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 g4 5 Bxf7+ (‘An almost obsolete variation. Some 40 years ago or more, I frequently played it, but came to the conclusion that it did not lead to such a lasting attack as the ordinary Muzio. When I sacrificed the bishop, one of the lookers-on asked what Gambit I called that, pointing to the next board. “That”, I said, “is the Bishop’s Gambit, and this is the Archbishop’s.” The Archbishop was present at the time.’) 5...Kxf7 6 Ne5+ Ke8 (‘The only move. Any other loses immediately.’) 7 Qxg4 Qf6 (‘The correct reply is 7...Nf6.’)

Source: BCM, September 1903, page 392.

(182)

For the complete game, see our feature article on Blackburne.

Stefan Bücker (Nordwalde, Germany) submits a game, lost against his brother, which he published on page 43 of his book Das neue Königsgambit (Stuttgart, 1986):

Stefan Bücker – Peter Bücker

Nordwalde Club Championship, 1975

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 d5 4 exd5 Nf6 5 Bb5+ c6 6 dxc6 Nxc6 7 d4 Bd6 8 O-O O-O 9 Bxc6 bxc6 10 c4 Bg4 11 Qd3 Qd7 12 Nc3 Rfe8 13 Ne2 g5 14 Nc3 h6 15 a3 Rad8 16 b4 c5 17 Nb5 Bf8 18 d5 Bf5 19 Qd1 a6 20 Nc3 cxb4 21 axb4 Bxb4 22 Bb2 Bc5+ 23 Kh1 Ng4 24 Na4 Ba7 25 Qd2 Re3 26 h3 Rd3 27 Qa5 Ne3 28 Ne5

28…Nxf1 29 Rxf1 Be4 30 Kh2 Rg3 31 Nf3 Rb8 32 Qc3 Rxb2 33 Nxb2 g4 34 White resigns.

Our correspondent is the editor of the German-language quarterly Kaissiber, which specializes in openings analysis and historical research. It is one of the most impressive chess magazines we have ever seen.

(2216)

The start of a game, with notes by Janowsky, which is given in full in our feature article on him.

Georg Marco – Dawid Janowsky

Sixth match game, S.S. Pretoria, 13 June 1904

King’s Gambit Declined

1 e4 e5 2 f4 Bc5 3 Qf3 (‘An innovation meriting consideration.’ [In fact, 3 Qf3 was played twice by Charousek in 1896, against Showalter and Maróczy.]) 3…Nc6 4 c3 d6 5 Bc4 Nf6 (‘5…Be6 was stronger.’) 6 d3 O-O (‘Premature, in view of the ease with which White sets up a king’s side attack. Here too 6…Be6 would be much better.’) 7 f5 (‘Hemming in the enemy queen’s bishop and threatening g4, followed by h4.’) 7…d5 8 Bb3! (‘8 Bxd5 Nxd5 9 exd5 Ne7 10 g4 Qxd5, etc. and 8 exd5 e4 9 dxe4 Ne5 10 Qe2 Nxc4 11 Qxc4 Nxe4, etc. would be to White’s disadvantage.’) 8…dxe4 9 dxe4 Qd6 10 Bg5 (‘With 10 g4 he could have put his opponent in a very tricky position.’)

Source: La Stratégie, 21 September 1904, pages 263-264.

3 Qf3 in the King’s Gambit Accepted was occasionally played by Capablanca in simultaneous exhibitions, and most notably against A. Chase in New York, 1922:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Qf3 Nc6 4 c3 Nf6 5 d4 d5 6 e5 Ne4 7 Bxf4 g5 8 Be3 h5

9 Nd2 Bg4 10 Nxe4 Bxf3 11 Nf6+ Ke7 12 Nxf3 Bh6 13 Nxg5 Bg7 14 Bd3 Bxf6

15 O-O Qg8 16 Rxf6 Rf8 17 Raf1 Nd8 18 b4 Qg7 19 h4 Ke8 20 b5 b6 21 Be2 Ne6 22 Bf3 Nxg5 23 Bxg5 Qh7 24 Bxd5 Qd3 25 Bc6+ Resigns.

Taking the game from the American Chess Bulletin, on pages 158-159 of The Unknown Capablanca (London, 1975) David Hooper and Dale Brandreth called 9 Nd2 ‘a fine positional sacrifice which should rank amongst the best ever made’ and commented regarding 15 O-O: ‘An astonishing reply. Is it possible for ordinary mortals to foresee such moves?’

Irving Chernev gave the game on page 224 of The Chess Companion (New York, 1968). His text had previously appeared on the inside front cover of the March 1955 Chess Review.

From pages 149-150 of the Literary Digest, 2 February 1901:

‘In a lecture, recently delivered in Chicago, on chess openings, Mr Pillsbury said that in modern practice among the great masters only two openings – the Ruy López and the Queen’s Pawn – are considered to retain the advantage of the first move for any length of time. He believed that the Berlin Defense of the Ruy López was the best. Of the Petroff Defense, which he brought into practise again in the St Petersburg tournament several years ago, he does not now entertain as good an opinion as he did then. He believes if White continues with 3 P-Q4 the advantage remains with the attack, and for that reason he has abandoned it. He agrees entirely with the principles laid down in Lasker’s Common Sense in Chess and says every great master must necessarily do so. Against the Evans Gambit he recommends Lasker’s defense or the refusal of the gambit. In either case the defense should obtain a better game.

He also holds that the Falkbeer Counter-Gambit against the King’s Gambit should yield the second player the superior, or at least equal, game. He dwelt at length on “the waiting move”, claiming there should be no such thing in a correct game of chess. Should a player at any time make an indifferent move like P-R3, simply because he knows of nothing better, there is an admission of weakness in his game. On the other hand, if such a move is made with the pre-conceived plan of making a general advance in the pawn formation, it is then a sign of strength. He is of the opinion that between even players in serious games the attack, with accurate play, should win about two games in ten, the others resulting in draws.’

(4202)

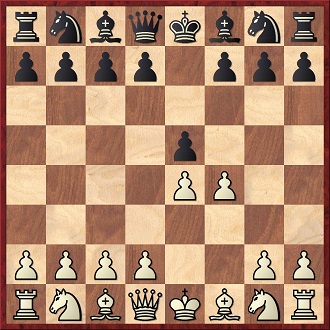

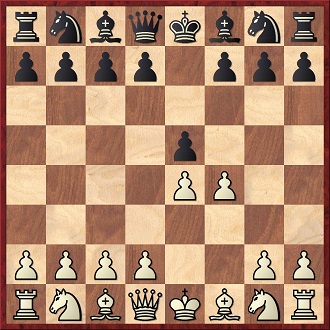

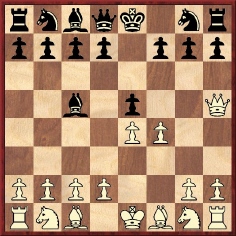

Page 94 of Chess Openings by F.J. Marshall (Leeds, 1904):

Position after 10 Bg2 Be6

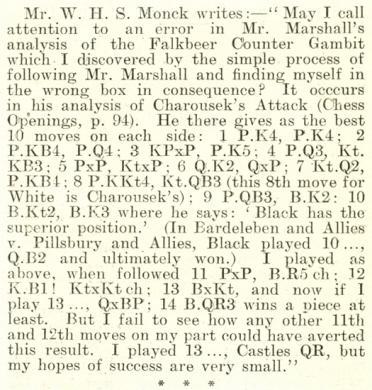

A comment by W.H.S. Monck was published on page 131 of the February 1910 Chess Amateur:

The Chess Amateur reverted to the subject when reviewing Griffith and White’s Modern Chess Openings (Leeds, 1911) on page 515 of the February 1912 issue:

‘... In the Chess Amateur Mr Monck complained of having been misled by Marshall’s Chess Openings in a variation of the Falkbeer Counter-Gambit, in which the master had left off with a remark that Black had the best of it when in fact the loss of a piece could not be avoided. This variation is given without comment p. 59 col. 25. We should wish to know how the able authors would reply to the obvious move 11 PxP.’

Page 69 of the second edition of Modern Chess Openings (London, 1913) had no mention of 10...Be6, giving instead (after 10 Bg2) the line 10...Qf7 11 Nxe4 fxe4 12 Bxe4 Bh4+ (13 Kd1 Be6) and referring to the 1902 consultation game opposing von Bardeleben and Pillsbury.

William Henry Stanley Monck, incidentally, was an eminent astronomer, as mentioned on page 153 of Chess Facts and Fables.

(6938)

From page 1 of Larsen’s Selected Games of Chess 1948-69 by Bent Larsen (London, 1970):

‘It appeared that my father knew the game, and we sometimes played. When I was 12 I beat him almost every time; then I entered the chess club. At that time I also began to borrow chess books at the public library. I even found a chess book at home – nobody knew how it had got into the house. Probably the former owner had forgotten it. This book had a certain influence on the development of my play. About the King’s Gambit it said that this opening is strong like a storm, nobody can tame it. In the author’s opinion modern chess masters were cowards, because they had not got the guts to play the King’s Gambit. Naturally, I did not like to be a chicken and, until about 1952, the favourite opening of the romantic chess masters was also mine.’

Which book was it?

(4475)

From Claes Løfgren (Randers, Denmark):

‘The book that influenced the young Bent Larsen’s choice of openings was Kan De spille Skak? by Andreas Nissen (Copenhagen, 1919). A second edition was published in 1923. The full introduction to the King’s Gambit (pages 81-82) reads:

“This important and enormously interesting opening is age-old and comes from Italy. In the language of this country ‘dare il gambetto’ means to put a leg forward. The opening was already referred to in a 1561 work by Ruy López. The King’s Gambit is a gigantic opening and demands a free spirit. It roars like a storm, and only giants can defy it. Nothing shows the impotence of the present day more than the fact that nobody believes himself capable of playing the King’s Gambit any longer. The chess masters shun it like the plague. In the King’s Gambit the chess spirit rises to dizzying heights, where the modern pawn technique apparatus fails like a bad motor.

Morphy valued the King’s Gambit very highly, and it was a fearful weapon in his hands. Adolph [sic] Anderssen immortalized it in his famous game against Kieseritzky – but then Anderssen was not a master whose only concern was points, points and more points, preferably paid for piece by piece by a business-wise tournament committee.”

Nissen was obviously an inveterate romantic and had little good to say about closed openings or the tournament players and praxis of his day. Often he was altogether unable to hide his contempt. About the Caro-Kann he commented on page 100:

“This opening is even worse than the ‘Sicilian Game’ and leaves all the initiative to White. It was introduced into playing practice by the Viennese player Kann, while the German Caro messed about with it, although it cannot be claimed that he improved it ...”

On the same page he wrote of the variation 1 e4 c6 2 c4:

“It cannot be asserted that with the move 2 c4 White obtains anything at all. He indicates with this move that he is as big a coward as Black, who, terrified by the sight of White’s first move e4, tremblingly drags his c-pawn to c6. The opponents match each other well.”

Andreas Nissen (1881-1950) wrote other manuals for beginners and books on the endgame, and he edited the chess column in the newspaper Berlingske Tidende. In his obituary on page 146 of the August 1950 Skakbladet “E.C.” characterized him as follows:

“... with Nissen, the Copenhagen Chess Club has lost one of its old, esteemed members, a gifted and well-informed man, an ardent chess enthusiast, and a splendid attacking player of the old school. He was devoid of ambition in chess, and rather sought in the game the satisfaction of a strong sense of chess aesthetics and need for excitement – circumstances which may explain why, despite his unquestionable chess talent and theoretical knowledge, he never reached the top as a practical player ...”’

(4480)

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) asks for information about Colonel (Oberst) Hippolyt Walter von Walthoffen (1830-1912), who had the ‘Walthoffen Attack’ named after him and won a well-known miniature against Gustav Zeissl in Vienna in 1899.

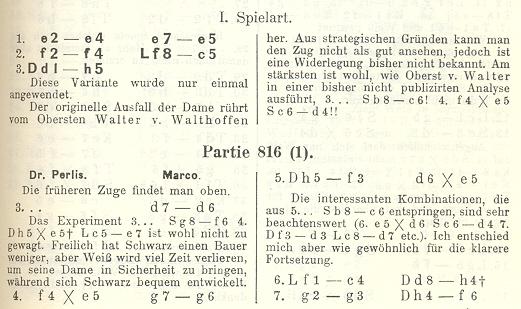

We begin by recalling that the Walthoffen Attack occurs in the King’s Gambit Declined: 1 e4 e5 2 f4 Bc5 3 Qh5.

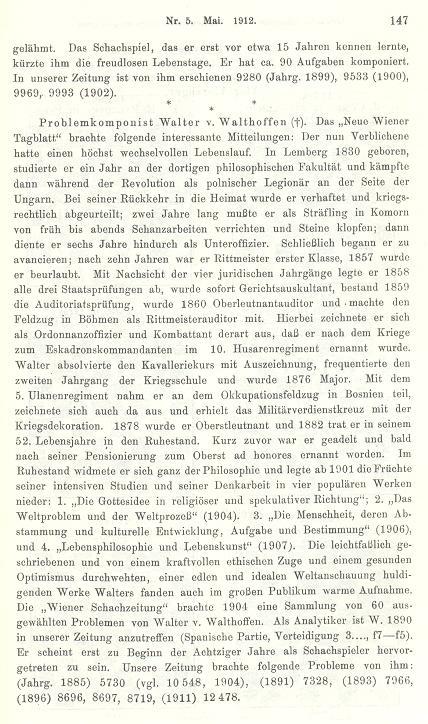

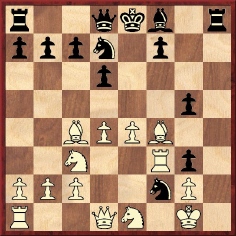

White’s third move was mentioned on page 781 of Bilguer’s Handbuch des Schachspiels (Berlin and Leipzig, 1922), the only game reference being to Perlis v Marco, Vienna, 1904, as published on pages 99-100 of the April 1905 Wiener Schachzeitung:

At move three it was commented that 3 Qh5 came from von Walthoffen (‘Der originelle Ausfall der Dame rührt vom Obersten Walter v. Walthoffen her’). This is the earliest reference we can currently offer for the ‘Walthoffen Attack’.

Page 59 of the February 1895 Deutsche Schachzeitung described him as ‘the well-known analyst and problem composer’ (‘der bekannte Analytiker und Problemcomponist’), but whereas there is no shortage of compositions by him in chess magazines of the time, we have come across little analytical work by him. One article, about 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 f5, was published on pages 161-165 of the June 1890 Deutsche Schachzeitung, and Curt von Bardeleben presented a follow-up item on pages 257-260 of the September 1890 issue. The same magazine (November 1899, pages 335-336) published this game:

Hippolyt Walter von Walthoffen – Johann Hermann Bauer1 f4 d5 2 d4 e6 3 e3 c5 4 c4 Nf6 5 Nf3 Nc6 6 Nc3 a6 7 Ne5 cxd4 8 exd4 Bb4 9 a3 Bxc3+ 10 bxc3 Ne4 11 Qd3 Na5 12 c5 f6 13 Nf3 Nb3 14 Rb1 Nxc1 15 Rxc1 Qa5 16 Ra1 Qxc3+ 17 Qxc3 Nxc3 18 Bd3 Bd7 19 Kd2 Ne4+ 20 Ke3 Bc6 21 Bxe4 dxe4 22 Nd2 f5 23 Nc4 Bd5 24 Ne5 Rc8 25 Rac1 Rc7 26 g4 Rf8 27 g5 Ke7 28 a4 Rfc8 29 a5 Bc6 30 Rhg1 Rh8 31 Rg3 Kf8 32 Rh3 Kg8 33 Rc3 Be8 34 Rh4 h5

35 d5 exd5 36 Kd4 Bc6 37 Rb3 Rc8 38 Nxc6 bxc6 39 Rb6 g6 40 Rxa6 Rh7 41 Rb6 Ra7 42 a6 Kf7 43 Rh3 Ke7 44 Rhb3 Kd7 45 Rb7+ Rc7 46 R3b6 h4

47 h3 (‘Zugzwang’, comments the German magazine.) 47...Kc8 48 Rxa7 Rxa7 49 Rxc6+ Rc7 50 Rxg6 Resigns.

The familiar win by von Walthoffen against Zeissl went 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 f5 4 d4 fxe4 5 Nxe5 Nxe5 6 dxe5 c6 7 Bc4 Qa5+ 8 Nc3 Qxe5 9 O-O d5 10 Bb3 Nf6 11 Be3 Bd6 12 g3 Bg4 13 Qd2 Bf3 14 Bf4, and Black announced mate in five with 14...Qf5 15 Nd1 Qh3 16 Ne3 Ng4 etc., although White has ‘spoilers’ at his disposal. Irving Chernev included the game in his book Logical Chess Move by Move, and it appears in a number of databases. The latter usually state ‘1898’, but on pages 79-80 of the May 1899 Wiener Schachzeitung the game was reported as having been played in the Vienna Chess Club on 25 March 1899.

That publication was in a section headed ‘casual games’ (‘Freie Partien’). On the other hand, page 39 of the March 1899 Wiener Schachzeitung had a crosstable for the 1898-99 Amateur Tournament of the Vienna Chess Club (won by L. Löwy) in which Zeissl lost a game to a player named as ‘Oberst v. Walter’. This was rendered as ‘von Walter’ on page 135 of the first volume of Chess Tournament Crosstables by Jeremy Gaige (Philadelphia, 1969).

The reference in Gaige’s book prompts another question from our correspondent, Rod Edwards: was that tournament participant Hippolyt Walter von Walthoffen? Leaving aside the plain surname ‘Walter’, we have found, in the innumerable occurrences of the names ‘von Walthoffen’ and ‘von Walter’ in the Deutsche Schachzeitung and the Wiener Schachzeitung, instances of each being described as a) a player, b) a problemist, c) an ‘Oberst’ and d) a ‘Doktor’. On the other hand, there are also cases of their being indexed as different persons. The question thus remains open. We add in passing that Gaige’s Chess Personalia (page 456) had ‘Walter von Walthofen [sic], Hippolyt’.

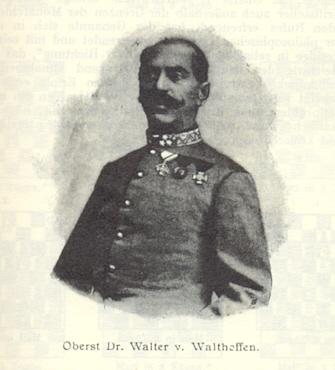

The illustration below appeared on page 77 of the February-March 1904 Wiener Schachzeitung, as an introduction to 60 of von Walthoffen’s problems (given on pages 78-83):

The article also announced the publication in early March 1904 of a philosophical work by him, Das Weltproblem und der Weltprozess. After his death a biographical note on page 147 of the May 1912 Deutsche Schachzeitung (taken from the Neue Wiener Tagblatt) listed three other philosophical works by him, as well as supplying an overview of his military career and his chess activity.

The ‘Walthoffen Attack’ was not mentioned in the above article, but it has not been forgotten. For an analytical discussion see, for instance, pages 15-18 of Das neue Königsgambit by Stefan Bücker (Stuttgart, 1986).

(4723)

Olaf Teschke (Berlin) writes:

‘On 5 August 2006 the Ostsee-Zeitung gave a sketchy biography of Hermann von Hanneken (1810-86). There are two lines named after him, 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 Nf6 and 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Bb4+ 5 c3 dxc3 6 O-O cxb2 7 Bxb2 Nf6 8 Ng5 O-O 9 e5 Nxe5, but I have not been able to find justification for this nomenclature on the basis of actual games. Are there any reliable sources?’

Readers’ suggestions will be welcome. So far, we have looked only at the King’s Gambit Accepted line. Von Hanneken contributed an article ‘Auch etwas über das Gambit des Läufers’ on pages 401-408 of the November 1850 Deutsche Schachzeitung, and four pages discussed 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 Nf6. We also note this game on pages 333-334 of the October-November 1862 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

Max Lange – Hermann von Hanneken1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 Qe2 Bc5 5 Nf3 Nc6 6 c3 O-O 7 d4 d5 8 exd5 Nxd5 9 Bxd5 Re8 10 Ne5 Qxd5 11 Bxf4 f6 12 Nd2

12...Bf5 13 O-O-O Qxa2 14 Ne4 fxe5 15 Bxe5 Nxe5 16 dxe5 Qa1+ 17 Kc2 Qa4+ 18 White resigns.

(4748)

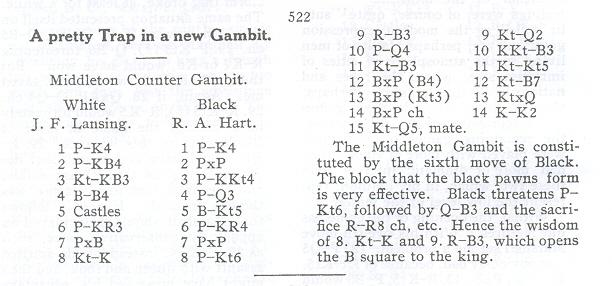

A number of databases give the following as a correspondence game played by J. Lansing and R. Hart in 1985:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 d6 5 O-O Bg4 6 h3 h5 7 hxg4 hxg4 8 Ne1 g3 9 Rf3 Nd7 10 d4 Ngf6 11 Nc3 Ng4 12 Bxf4 Nf2

13 Bxg3 Nxd1 14 Bxf7+ Ke7 15 Nd5 mate.

In reality, the game had been published on page 24 of the November 1907 issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine:

(4792)

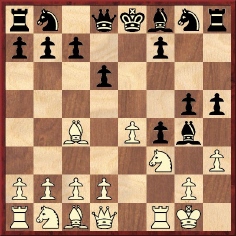

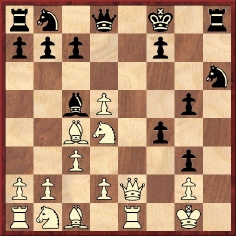

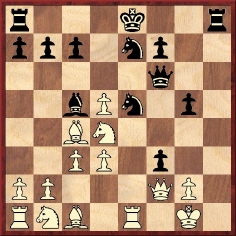

C.N. 4792 gave a game between J.F. Lansing and R.A. Hart which began 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 d6 5 O-O Bg4 6 h3 h5, and information is now sought on the origins of this line, the ‘Middleton Counter-Gambit’. The game below was presented on page 267 of the June 1908 Chess Amateur:

R.A. Hart – P.H. Seamon1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 d6 5 O-O Bg4 6 h3 h5 7 hxg4 hxg4 8 Nd4 g3 9 Qg4 d5 10 exd5 Bc5 11 Re1+ Kf8 12 c3 Nh6 13 Qe2

13...Nc6 14 dxc6 Bxd4+ 15 Kf1 Nf5 16 Qe4 Qf6 17 cxb7 Rb8 18 Ke2 Bf2 19 Rf1 Kg7 20 Kd1 Rbe8 21 Qd5 Rd8 22 Qxf7+ Qxf7 23 Bxf7 Ne3+ 24 Ke2 Nxf1 25 Bc4 Rhe8+ 26 White resigns.

A note at White’s eighth move mentioned ‘an American leaflet on this opening which gives four specimen games’. Does any reader have a copy?

Page 173 of the March 1909 Chess Amateur referred to ‘this remarkable opening’ when giving another game played in America, contributed by S. Reid Spencer and annotated by W.P. Turnbull:

N.N. – Lohmann1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 d6 5 O-O Bg4 6 h3 h5 7 hxg4 hxg4 8 Nd4 Qf6 9 c3 d5 10 Qxg4 Nd7 11 exd5 Bc5 12 Re1+ Ne7 13 d3 Ne5 14 Qe2 f3 15 Qf2

15...Rh2 16 Kxh2 Ng4+ 17 Kg3 Nxf2 18 Kxf2 fxg2+ 19 Kxg2 O-O–O 20 Be3 g4 21 Nd2 Bd6 22 Ne4 Qe5 23 Nxd6+ cxd6 24 Bf2 Qg5 25 Re3 Ng6 26 Rae1 a6 27 a4 Kd7 28 Bg3 Rh8 29 b4 Rh3 30 Kf2 f5 31 Ne6 Qh6 32 a5

32...Rxg3 33 White resigns.

When a third game was published on pages 77-78 of the December 1909 Chess Amateur, again with notes by W.P Turnbull, the players were not identified, although it was stated that this score too had been contributed by S. Reid Spencer:

N.N. – N.N.1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 d6 5 O-O Bg4 6 h3 h5 7 hxg4 hxg4 8 Nh2 g3 9 Ng4 Qe7 10 Re1 f6 11 Bxg8

11...Nd7 12 Bd5 Qh7 13 Kf1 Qh1+ 14 Ke2 Qxg2+ 15 Kd3 Nc5+ 16 Kd4

16...Bg7 17 Kc4 c6 18 Bxc6+ bxc6 19 Rg1 Qxe4+ 20 d4 Qd5+ 21 Kc3 Na4+ 22 Kd3 Qb5+ 23 Kd2 O-O-O 24 Na3 Qf5 25 b3 Qa5+ 26 White resigns.

As yet we have not ascertained why the name Middleton was applied to the gambit. It may be a reference to E.E. Middleton, who was active in Belgian chess circles in the first decade of the twentieth century, but can a reader take the matter further?

(4860)

From Neil Brennen (Spring City, PA, USA):

‘The Middleton Counter-Gambit is named after Thomas J. Middleton of Texas. I mentioned this in passing in my article “The Process of Creation”’.

Our correspondent’s article quoted from a feature ‘Chess in Texas By a Texan’ on page 171 of the October 1898 American Chess Magazine, which stated:

‘Mr T.J. Middleton, of Waxahachie, ... has played chess since 1870, is very original in his games, always seeking new lines of play. He has originated a reply to the King’s Gambit wherein Black sacrifices a bishop on the sixth move, that has attracted some notice among Texas players.’

A small photograph of Middleton appeared on the same page of the American Chess Magazine:

(4864)

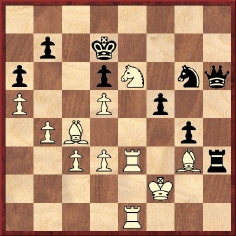

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 d6 5 O-O Bg4 6 h3 h5 7 hxg4 hxg4 8 Nh2 g3 9 Ng4 Nf6 10 Nc3 Rh4 11 Ne3 fxe3 12 dxe3 g4 13 Qd4 Bg7 14 e5 Nc6 15 Qf4 Nxe5 16 Qxg3 Nh5 17 Qf2 Nf3+ 18 gxf3 g3 19 Qd2 Rh2 20 Qd5 Rh1+ 21 Kg2

21...Nf4+ 22 exf4 Rh2+ 23 Kg1 Bd4+ 24 Qxd4 Qh4 25 White resigns.

This game comes from page 327 of the August 1916 Chess Amateur. Concerning the occasion, the only information provided is that the players were ‘Mac R.’ and ‘Hart’. The magazine’s source was the Boletín de Ajedrez (Mexico).

(7125)

Graham Clayton (South Windsor, NSW, Australia) has found this game between R.A. Hart and C.C. Lee on page 3 of the Sunday Times (Perth, Western Australia), 15 February 1903: 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 d6 5 O-O Bg4 6 h3 h5 7 hxg4 hxg4 8 Nd4 Qf6 9 c3 Nd7 10 Qxg4 Ne5 11 Qe2 g4 12 d3 g3 13 Bxf7+ Qxf7 14 Rxf4, after which the newspaper stated that (according to its source, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle) Black now gave mate in 12.

We have traced the game on page 21 of the 30 November 1902 edition of the Eagle. The heading reported that it was ‘played by correspondence between R.A. Hart of Baton Rouge, La and C.C. Lee of Boston, Mass., in the Middleton counter gambit tournament’.

(7130)

‘Efim Bogoljubow (1899-1952) was a chubby, bombastic drunkard known for his delusional thinking that he was invincible ...’

That comes from the very start of King’s Gambit by Paul Hoffman (New York, 2007), page ix. (‘1899’ is the book’s first date and is a decade out.)

(5273)

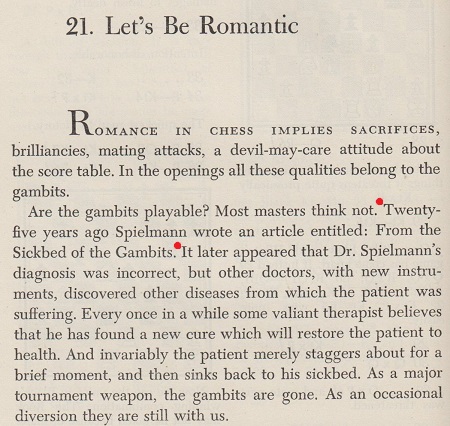

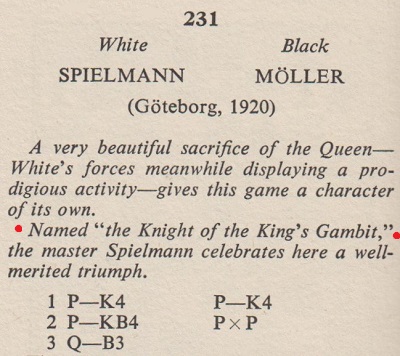

Further to the references to Rudolf Spielmann in Chess: the Need for Sources, the passage below comes from page 111 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

Can the original text be traced?

(8579)

From page 3 of Meet the Masters by Max Euwe (London, 1940):

‘Ordinary mortals can envy Alekhine’s genius in the discovery of charming and startling combinations; the more skilful player who feels himself quite capable of executing such combinations has a different feeling on the subject. To quote Spielmann, who is surely competent to pass an opinion on combinative skill: “I can comprehend Alekhine’s combinations well enough; but where he gets his attacking chances from and how he infuses such life into the very opening – that is beyond me. Give me the positions he obtains, and I should seldom falter. Yet I continually get drawn games, even out of the King’s Gambit.”

Well said, Master Spielmann! Alekhine’s real genius is in the preparation and construction of a position, long before combinations or mating attacks come into consideration at all.’

In case it helps in tracing the original of Spielmann’s words, below is the relevant section of pages 2 and 3 of the Dutch edition of Euwe’s book, Zóó schaken zij! (Amsterdam, 1938):

(8603)

From page 136 of The World’s a Chessboard by Reuben Fine (Philadelphia, 1948):

Next, a line from a column by Robert Byrne in the New York Times, 8 October 2000:

‘In the 1930s, the great champion of the gambit, Rudolph [sic] Spielmann, wrote an article titled, “From the Sickbed of the King's Gambit”.’

On page 171 of Impact of Genius (Seattle, 1992) R.E. Fauber indicated that Spielmann’s article was written in 1926.

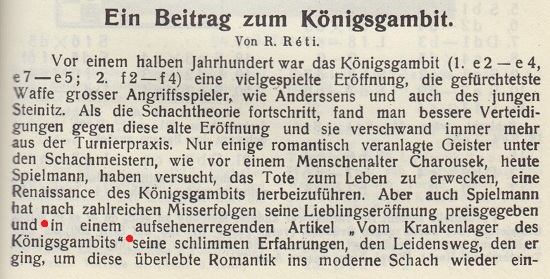

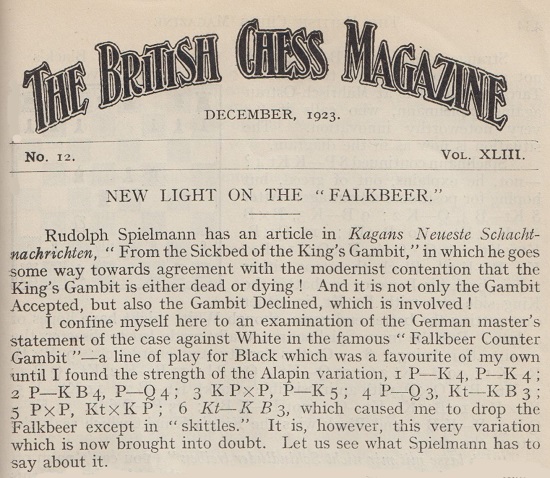

Many writers have referred to the article without any sign of having read it, and the date of its appearance is not altogether straightforward. If, as sources state, it was published in the July-September 1924 issue Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, how could Réti have mentioned it at the start of an article on pages 317-320 of the December 1923 Wiener Schachzeitung?

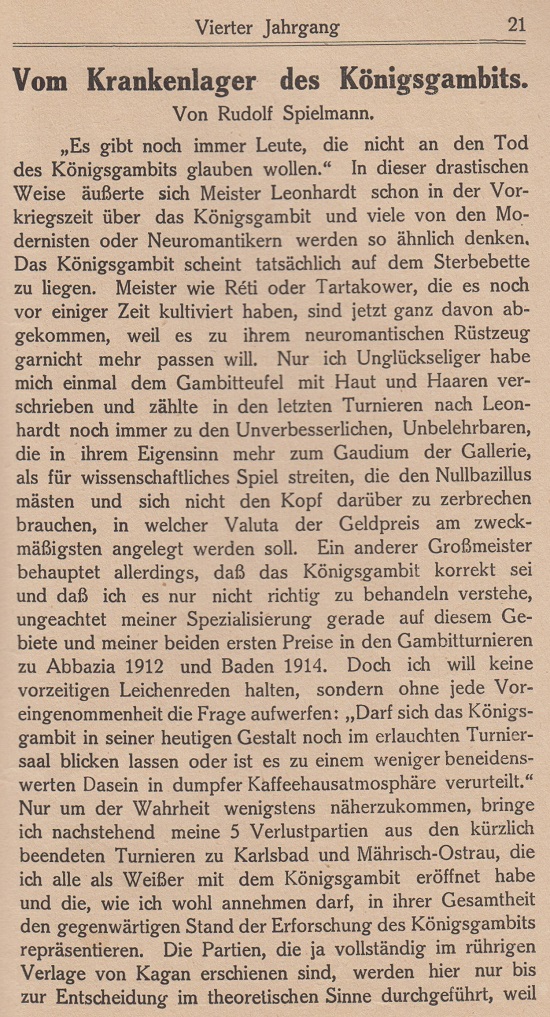

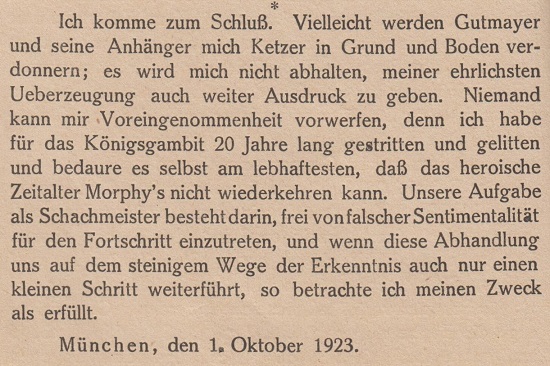

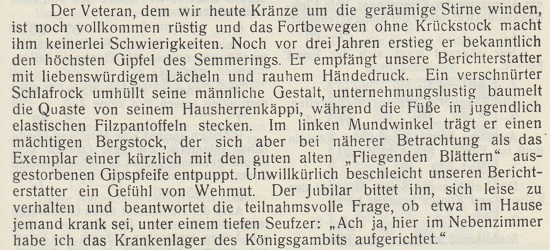

The answer is that the publication schedule of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten was even more erratic than usual, and the July-September 1924 issue comprised games and articles from 1923. Spielmann’s ‘Vom Krankenlager des Königsgambits’ appeared on pages 21-36. The first page and the conclusion are shown below, and it will be seen that the article was dated 1 October 1923.

Under the title ‘New Light on the “Falkbeer”’, P.W. Sergeant discussed Spielmann’s ‘From the Sickbed of the King’s Gambit’ article on pages 433-434 of the December 1923 BCM. The magazine had two follow-up articles (January 1924, pages 1-2, and February 1924, page 59).

The theme was also taken up in a spoof article ‘Spielmann 46 Jahre alt!!’ on pages 35-37 of the February 1929 Wiener Schachzeitung:

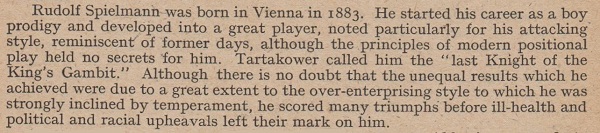

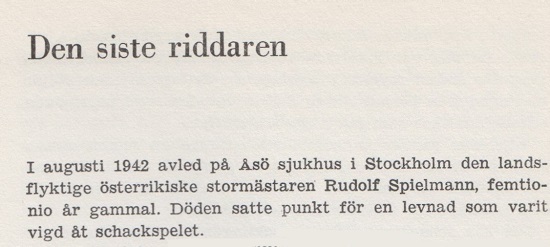

A related matter is the term, ostensibly coined by Tartakower, ‘The Last Knight of the King’s Gambit’ to describe Spielmann. As shown below, the nickname appeared in J. du Mont’s obituary of Spielmann on page 10 of the January 1943 BCM, but how far back can it be traced?

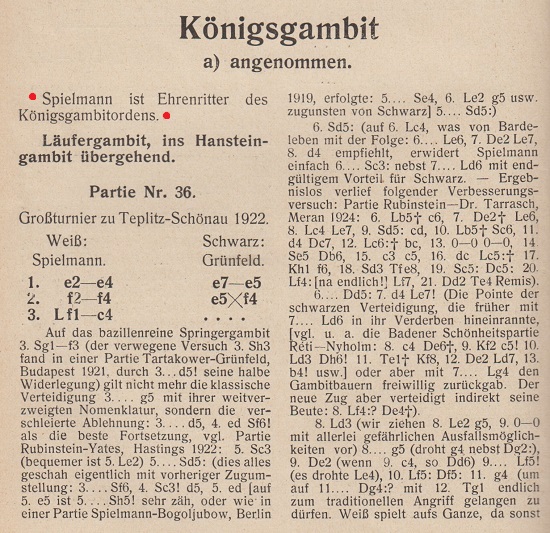

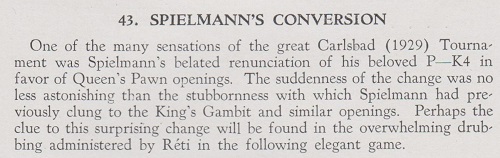

The heading in the King’s Gambit section on page 212 of Tartakower’s Die hypermoderne Schachpartie (Vienna, 1924) had ‘Spielmann ist Ehrenritter des Königsgambitordens’ (‘Spielmann is an honorary knight of the King’s Gambit Order’):

The introduction to a game on page 296 of book one of 500 Master Games of Chess by Tartakower and du Mont (London, 1952) referred to ‘the Knight of the King’s Gambit’:

The word ‘last’ is absent.

This leads to the question of whether it is really a coincidence that Réti wrote similarly, but with the word ‘last’, in the section on Spielmann on page 236 of Die Meister des Schachbretts (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1930):

‘Spielmann ist der letzte Barde des Gambitspiels und wollte insbesonders das Königsgambit zu neuem Leben erwecken.’

In the English edition, Masters of the Chess Board (London, 1933), the translation (page 127) was:

‘Spielmann is the last bard of the Gambit Game, and what he wanted to revive especially was the King’s Gambit.’

Regarding ‘The Last Knight of the King’s Gambit’, two tentative conclusions thus seem possible: either Tartakower used that full term in a text which has yet to be traced or the description resulted from a mistake (by du Mont or by an earlier writer) which combined remarks on Spielmann by Tartakower and Réti.

In any case, ‘The Last Knight’ became attached to Spielmann’s name. It was, for example, the title of a chapter about him on pages 60-64 of Strövtåg i schackvärlden by G. Ståhlberg (Skara, 1965):

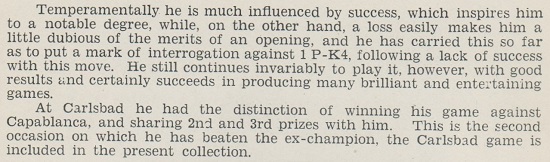

As is well known, in the late 1920s Spielmann began opening with 1 d4 far more often than previously. From page 85 of Chess Strategy and Tactics by F. Reinfeld and I. Chernev (New York, 1933):

The game was Réti’s victory in 31 moves at Trenčianske Teplice, 1928.

In conclusion, though, the following may be noted from page 80 of Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929), in the section on Spielmann:

(10265)

From page 96 of Réti move by move by Thomas Engqvist (London, 2017):

‘In Masters of the Chess Board, Réti mentions that Spielmann was the last bard of the Gambit Game, who especially wanted to revive the King’s Gambit. Following Spielmann’s successful result at Carlsbad in 1929, where he shared second place with Capablanca and even managed to beat him, he constantly adopted 1 d4. This conversion made his colleagues nickname him not “the last knight of the King’s Gambit” but “the last knight of the Queen’s Gambit”.’

No particulars were offered.

(10348)

See also:

The Immortal Game (Anderssen v Kieseritzky);

A Chess Gamelet (the Quaade Gambit);

To the Archives

for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.